Significance

Design of nanoscale materials for applications that interface with biological systems requires that mechanisms of nanoparticle interaction with cellular membranes be understood, both to improve performance and to assess nanomaterial safety. We integrated experimental and computational approaches to resolve the outstanding question of whether the function of membrane-embedded ion channels can be perturbed via nanoparticle-induced modulation of membrane mechanical properties. We show that anionic nanoparticles disrupt channel activity indirectly by perturbing local properties of the surrounding lipid bilayer. Our results indicate that nanoparticle effects on membrane protein function do not require direct interaction; effects can be mediated via changes in bilayer mechanical properties. Such indirect effects warrant consideration in nanomaterial safety evaluations and suggest potential applications in modulating cellular function.

Keywords: nanoparticle, ion channel, molecular dynamics, electrophysiology, phospholipid

Abstract

Understanding the mechanisms of nanoparticle interaction with cell membranes is essential for designing materials for applications such as bioimaging and drug delivery, as well as for assessing engineered nanomaterial safety. Much attention has focused on nanoparticles that bind strongly to biological membranes or induce membrane damage, leading to adverse impacts on cells. More subtle effects on membrane function mediated via changes in biophysical properties of the phospholipid bilayer have received little study. Here, we combine electrophysiology measurements, infrared spectroscopy, and molecular dynamics simulations to obtain insight into a mode of nanoparticle-mediated modulation of membrane protein function that was previously only hinted at in prior work. Electrophysiology measurements on gramicidin A (gA) ion channels embedded in planar suspended lipid bilayers demonstrate that anionic gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) reduce channel activity and extend channel lifetimes without disrupting membrane integrity, in a manner consistent with changes in membrane mechanical properties. Vibrational spectroscopy indicates that AuNP interaction with the bilayer does not perturb the conformation of membrane-embedded gA. Molecular dynamics simulations reinforce the experimental findings, showing that anionic AuNPs do not directly interact with embedded gA channels but perturb the local properties of lipid bilayers. Our results are most consistent with a mechanism in which anionic AuNPs disrupt ion channel function in an indirect manner by altering the mechanical properties of the surrounding bilayer. Alteration of membrane mechanical properties represents a potentially important mechanism by which nanoparticles induce biological effects, as the function of many embedded membrane proteins depends on phospholipid bilayer biophysical properties.

Nanoparticles, virus-sized objects that can be composed of organic or inorganic materials, show considerable promise as bioimaging agents, drug delivery vehicles, and even as therapeutic agents themselves (1–3). Many of these technologies would benefit from a deeper understanding of how nanoparticles interact with biological membranes to enable the design of new nanomaterials with improved efficiencies and to minimize negative biological impacts. Nanoparticle properties such as core composition, size, shape, and surface functionalization can each influence membrane interactions and subsequent biological outcomes, including internalization (4–10), membrane damage (11–13), alteration of membrane function (14, 15), and initiation of cellular signaling cascades (16). Experimental model membrane systems such as lipid vesicles (17–20), supported lipid bilayers (21–24), lipid monolayers (25, 26), and planar suspended bilayers (27) have been employed to gain insight into mechanisms of nanoparticle interaction with biological membranes and to inform in vivo investigations that correlate nanoparticle properties to cellular outcomes such as toxicity. For example, the binding to and disruption of model membranes by poly(ethyleneglycol)-functionalized quantum dots and polycation-coated diamond nanoparticles have been correlated to bacterial membrane damage that ultimately reduces cell viability (17, 28, 29). Amphiphilic and lipophilic nanoparticles can induce defects in model membranes and cells (30) or embed in lipid bilayers (27, 31). Atomistic and coarse-grained molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and analytical modeling have provided important insights into nanoparticle interaction with the lipid bilayer of cellular membranes (13, 31–33). While the majority of prior investigations of nanoparticle interaction with model membrane systems have relied on lipid bilayers composed of single phospholipids or binary mixtures (19, 23, 24, 26, 34), recent efforts have begun to investigate the influence of other important membrane components on nanoparticle binding such as cell surface glycans and membrane proteins (35–37) to provide deeper insight into how the chemistry of cell surfaces facilitates nanoparticle binding.

Ion channels comprise a class of embedded membrane proteins that are critical for maintaining cellular homeostasis and other biological functions (e.g., epithelial transport, immune cell activation, conduction of nerve impulses, muscle contraction) (38). Nanoparticles can disrupt the function of ion channels in membranes (14, 39–41), altering ion channel gating (39) and membrane potentials (14, 42). For example, while anionic nanoparticles are often considered nontoxic (29), they have been shown to preferentially interact with neuronal membranes (vs. glial cells) and modulate their excitability, whereas such effects were not induced by cationic or neutral nanoparticles (15). Computational and experimental studies have provided evidence that some nanomaterials can decrease ion channel function by blocking the channel entrance or by altering protein conformation via binding to extracellular domains (40, 43–45). Nanoparticle-induced perturbation to the mechanical properties of phospholipid bilayers has also been invoked as a potential explanation for observed disruption of ion channel function (39, 41, 42). The binding of nanoparticles to phospholipid bilayers can alter the mechanical properties of membranes (19), but evidence correlating changes in membrane properties to altered ion channel (or other membrane protein) function has been inconclusive.

Here, we combine experiments and simulations to investigate nanoparticle−membrane interactions and concomitant effects on the function of embedded ion channels. We employed voltage clamp electrophysiology measurements on planar suspended lipid bilayers to demonstrate that anionic gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), often considered among the most benign nanoparticles (29), alter the function of embedded mechanosensitive gramicidin A (gA) ion channels without disrupting the membrane itself. Assembly of gA monomers into membrane-spanning, ion-conducting dimers is sensitive to the bilayer deformation energy (46). We used attenuated total reflectance−Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy and MD simulations to obtain evidence that anionic AuNP interactions subtly change membrane mechanical properties without directly altering the structure of embedded gA dimers. Our results provide insight into an indirect, phospholipid bilayer-mediated mode of nanoparticle-induced modulation of membrane protein function that was previously hypothesized, but not demonstrated experimentally (39, 41, 42). Indirect effects of nanoparticles mediated by changes in the biophysical properties of the lipid bilayer are expected to influence the function of membrane proteins—both mechanically gated ion channels (for which gA serves as a model) and others, whose activities exhibit sensitivity to the properties of the bilayer (46, 47). Our study also serves as a proof-of-concept demonstration of modeling a functional membrane system to assess the effects of nanoparticle binding on ion channel function.

Results

Anionic AuNPs Impact Ion Channel Function.

Electrophysiology was employed to measure the impact of AuNPs on the function of gA ion channels embedded in 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPhPC) bilayers (see Materials and Methods). Bilayers composed of DPhPC are frequently used in studies of ion conductivity because they exhibit characteristics desirable for electrophysiology studies, including high mechanical and chemical stability, high electrical resistance, and low ion and water permeability, and they remain in the biologically relevant liquid crystalline (i.e., fluid) phase over a broad temperature range (−120 °C to 120 °C) (48). The gA channel is a well-studied bacterial mechanosensitive peptidic ion channel (49–52) that shares several features with larger ion channels, including the dependence of its ion gating on bilayer deformation (46, 53) and the presence of tryptophan residues at the bilayer−solution interface (54). The gA-containing lipid bilayers provide a convenient and robust platform to investigate membrane-mediated impacts on ion channel function.

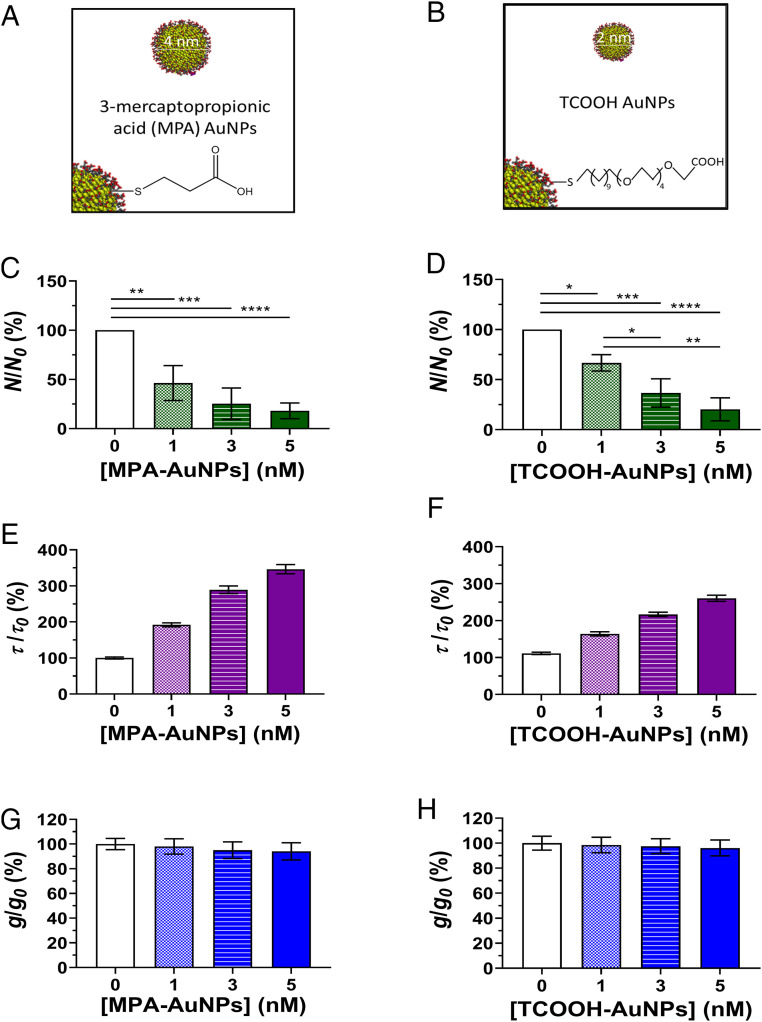

AuNPs were functionalized with either short (mercaptopropionic acid, MPA) or long (mercaptodecanoic-tetraethyleneglycol-carboxylate, TCOOH) anionic ligands to probe the presentation of carboxyl groups on interactions with gA-containing membranes (SI Appendix, Figs. S1 and S2 and Table S1). The MPA-AuNPs exhibited ζ-potentials of −29.4 ± 0.99 mV and underwent considerable aggregation in the buffer used for electrophysiology experiments. Specifically, while MPA-AuNPs possessed a core diameter of 5.4 ± 1.6 nm based on transmission electron microscopy (TEM) measurements (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), the hydrodynamic diameter measured in electrophysiology buffer was 360 ± 61 nm (SI Appendix, Table S1). TCOOH-AuNPs in electrophysiology buffer had a ζ-potential of −8.9 ± 0.40 mV and aggregated to a smaller extent than MPA-AuNPs (core diameter = 2.1 ± 0.2 nm, hydrodynamic diameter = 20 ± 15 nm; SI Appendix, Fig. S2 and Table S1). The MPA-AuNPs and TCOOH-AuNPs thus had distinct sizes, aggregation states, and ζ-potentials in the buffer used here.

Ion channel function was first measured for gA-containing membranes by adding anionic AuNPs to both sides of the membrane to minimize any electrophoretic effects or membrane pressure changes that might complicate interpretation of changes in ion channel function. Ion channel function was quantified for embedded gA ion channels by measuring the number (N(t)), lifetime (τ), and single-channel current (g) via voltage clamp electrophysiology (Fig. 1 A and B). Exposure of gA-containing membranes to a gradient of either TCOOH- or MPA-AuNPs reduced gA ion channel activity (number of channels per unit time; P < 0.05) and extended single-channel lifetimes (P < 0.001) in a dose-dependent manner, but did not alter single-channel current (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

Fig. 1.

Primary experimental and computational approaches. (A) Schematic of the voltage clamp electrophysiology setup used to study ion channels embedded in suspended bilayers. Cis and trans refer to sides of the membrane with respect to the position of the viewing window (i.e., from the vantage point of the user). (B) Electrical current trace for gA embedded in a DPhPC bilayer bathed in symmetric solutions of 0.15 M KCl buffered to pH 7 with 0.01 M Hepes. A +50-mV transmembrane potential was applied to the trans well such that cations flow to the cis well through open gA channels. Each current step on the electrophysiology traces of current versus time on Left corresponds to the number of conducting channels in the individual bilayers depicted in Right. (C and D) Illustration of the initial configuration of the MD system after assembly. The system shown here includes an MPA-AuNP assembled with a gA dimer embedded in a DPhPC lipid bilayer. For clarity, water and ions are not shown; C provides top-down view, and D depicts a side view.

Fig. 2.

Gold nanoparticles functionalized with (A) MAP or (B) TCOOH ligands (C and D) reduced normalized channel activity, (E and F) increased channel lifetimes (τ), and (G and H) had no effect on single-channel current at the nanoparticle concentrations used (1 nM to 5 nM, number concentration). Changes in normalized channel activity (N/N0), lifetime (τ/τ0), and single-channel current (g/g0) are shown for each nanoparticle type where the 0 subscript indicates the value prior to introduction of nanoparticles. Nanoparticles were added to both sides of the planar suspended bilayer lipid membrane with a +50-mV potential applied through the trans electrode. Channels were sampled in MPA- and TCOOH-AuNP experiments over 6.5 and 3.0 min, respectively. In C and D, statistical significance is denoted by asterisks: P < 0.05 (*), P < 0.01 (**), P < 0.001 (***), P < 0.0001 (****). In E and F, all differences are significant (P < 0.05). The normalized single-channel currents in G and H do not differ (P > 0.05). Plots display the results of triplicate experiments; error bars represent 1 SD.

Similar trends were observed for changes in ion channel function when 1 nM MPA-AuNPs was introduced to only the side of the membrane corresponding to the exterior (extracellular side) of a biological cell (SI Appendix, Figs. S4 and S5 and Table S6). We note that, although the terminal carboxylate groups of ligands decorating the AuNPs may bind potassium cations, the number of ions sequestered at the nanoparticle concentration used would be insufficient to appreciably change the K+ concentration of the solution. Using ligand densities reported in SI Appendix and assuming that every ligand is deprotonated and binds one K+ cation, we find that 5 nM MPA- and TCOOH-AuNPs (the highest concentrations used) would decrease the K+ ion concentrations by <0.01%. This change in K+ concentration is too small to appreciably alter channel conductance. Indeed, single-channel current is unaltered by exposure to the anionic AuNPs over the concentration range used (Fig. 2 G and H).

The observed changes in the number of gA channels and their lifetimes is instead largely consistent with a change in membrane mechanical properties, although activity and lifetime do not change in parallel as they do for molecular species (55). We note that dosing with free malonate (chosen as a free ligand control) at a concentration equivalent to total ligand on 1 nM MPA-AuNPs (see SI Appendix, Fig. S6 and Materials and Methods for details) did not significantly alter channel activity or single-channel current (P > 0.05), but reduced channel lifetimes relative to control (P < 0.05; SI Appendix, Fig. S6), in contrast to the increase in lifetime observed for both MPA- and TCOOH-AuNPs. Taken together, our results indicate that anionic AuNPs alter gA function similarly despite differences in carboxyl-bearing ligands (MPA vs. TCOOH), aggregation state (∼360 nm vs. 20 nm hydrodynamic diameter), and ζ-potential (approximately −9 mV vs. −29 mV), but that the effect of the nanoparticles differs mechanistically from that of free ligand in solution.

Anionic AuNPs Do Not Impact gA Conformation as Assessed by Vibrational Spectroscopy.

We used ATR-FTIR spectroscopy to probe perturbations of gA embedded in DPhPC vesicles induced by interactions with MPA- or TCOOH-AuNPs (Fig. 3). We focused our analysis on the amide I (dominated by backbone C=O stretching vibrations) and amide II (dominated by N–H stretching vibrations) regions of the vibrational spectra. The amide I band is particularly sensitive to secondary structure of the peptide backbone (56). The FTIR spectra of gA-containing vesicles exposed to MPA- or TCOOH-AuNPs were first referenced to gA-free vesicles to assess gA-related peaks in the amide I and II regions (Fig. 3A). The amide I peaks at 1630 cm−1 and ∼1668 cm−1 (shoulder) and the amide II peak at 1548 cm−1 for gA-containing vesicles are consistent with previously reported vibrational spectra for gA ion channels embedded in lipid vesicles (57–59). Exposure to MPA- or TCOOH-AuNPs (Fig. 3A) resulted in a reduction in peak intensities relative to gA-containing vesicles alone, but peak positions remained unchanged.

Fig. 3.

Amide I and II regions in the infrared absorbance spectra of gA-containing DPhPC vesicles before and after exposure to 100 nM of the indicated nanoparticle. Spectra were referenced against (A) DPhPC vesicles lacking gA and (B) DPhPC vesicles containing gA.

We also referenced spectra for gA-containing vesicles exposed to AuNPs to gA-containing vesicles alone, to isolate peak intensity changes specific to nanoparticle exposure (Fig. 3B). Amide I and II absorbances decreased for gA-containing vesicles exposed to MPA- or TCOOH-AuNPs compared to gA-containing vesicles alone (Fig. 3B), resulting in inverted peaks (compared to spectra in Fig. 3A). However, amide I and II peak ratios were similar for gA-containing vesicles exposed to MPA- or TCOOH-AuNPs (Fig. 3B), consistent with interactions being similar for both AuNP types. We note that peak shapes in the amide I and II regions for gA-containing vesicles exposed to AuNPs (referenced to gA-containing vesicles) were similar to gA-containing vesicles alone (referenced to DPhPC vesicles). Thus, the primary effect of exposing gA-containing vesicles to AuNPs was a uniform decrease in overall peak intensity across the amide I and II regions without changing relative peak positions or peak shapes. Based on these combined results, we conclude that any perturbation in gA conformation due to interaction with anionic AuNPs was minimal.

MPA-AuNPs Perturb Local Membrane Properties.

To obtain further mechanistic insight into anionic AuNP interaction with gA ion channels embedded in lipid bilayers, we performed MD simulations on a single MPA-AuNP in proximity to a single gA ion channel embedded in a DPhPC bilayer. We note that MPA- and TCOOH-AuNPs differ in several relevant properties (SI Appendix, Table S1), but experimental results are consistent with similar interactions with gA-containing bilayers. We conducted further simulations for a TCOOH-AuNP as well as four MPA-AuNPs aggregated together. Both show behaviors (SI Appendix, Figs. S13–S15) qualitatively similar to the single MPA-AuNP; thus our analysis focused on the MPA-AuNP system. We found that, regardless of the titration state (fully or half deprotonated) of the MPA ligands, the MPA-AuNP remains on the lipid bilayers for the majority of the 100-ns simulations with a distance of ∼2.5 Å to 5 Å (Fig. 4A), indicating stable adsorption. The nanoparticle, however, did not consistently exhibit attraction to the gA dimer; it remained close to the gA dimer in some trajectories, but drifted away in others (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

The minimal distances (A) between MPA-AuNP and the DPhPC bilayer and (B) between MPA-AuNP and the gA dimer embedded in the DPhPC bilayer during a 100-ns molecular dynamics simulation; the MPA-AuNP contains either 100% (full) or 50% (half) MPA ligands in the deprotonated form, and each set-up was simulated in two independent replicas. (C) Snapshots from MD simulations illustrating that the MPA-AuNP interact directly with lipid molecules regardless whether it is near or far from the gA dimer. The snapshots are from simulations of the half-deprotonated MPA-AuNP (i.e., 35 out of 72 MPA ligands are charged) assembled with a gA dimer embedded in a DPhPC lipid bilayer. For clarity, water and ions are not shown, and only phosphorus (tan) and nitrogen (blue) atoms in phospholipid head groups are shown for lipids.

We computed the root-mean-square difference of the gA backbone with respect to the crystal structure (SI Appendix, Fig. S7) and the number of backbone hydrogen bonds formed within the gA dimer (SI Appendix, Fig. S8) from the MD trajectories. In general, the results indicate that the presence of MPA-AuNP leads to very little perturbation on the gA structure, in agreement with FTIR results. To test the generality of the observed trends, we also conducted simulations for MPA-AuNP with a gA embedded in a 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC) bilayer. As shown in SI Appendix, Figs. S9 and S10, the mode of interaction between MPA-AuNP and gA is similar for both DPhPC and DMPC bilayers.

Since little direct impact on the gA channel from the MPA-AuNP is observed, we hypothesized that the effect on the gA channel lifetime stems from a change in local lipid properties upon MPA-AuNP adsorption. As discussed below and shown by Andersen and coworkers (60), local bilayer thickness (i.e., hydrophobic mismatch) and mechanical properties play an important role in determining the gA channel lifetime. To focus on the effect of MPA-AuNP on lipid properties, we measured the hydrophobic thickness and area compressibility modulus of the bilayer in MD simulations of MPA-AuNP assembled with a lipid bilayer without the gA dimer. The hydrophobic thickness of the bilayer is commonly defined as the average thickness given by C2 carbon atoms of the acyl tail of lipids in opposing leaflets (52), and the area compressibility modulus (KA) is related to the mean square fluctuation in lipid area (A) (61),

where kB is the Boltzmann constant and T is absolute temperature.

The impact of MPA-AuNP adsorption on local lipid properties was evaluated for a DPhPC bilayer with several independent 100-ns trajectories in the presence of an MPA-AuNP in either titration state. Since the DPhPC bilayer is rather stiff due to the packing of the methyl groups along the acyl chains, adsorption of the MPA-AuNP did not lead to significant local thinning of the bilayer, as shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S11; that is, the mean hydrophobic thickness is comparable in the presence and absence of the nanoparticle when the magnitude of thermal fluctuations is considered (SI Appendix, Fig. S12 C and D). By comparing the area compressibility moduli for different segments of the MD trajectory, we observe that the segment where AuNP is adsorbed on DPhPC consistently exhibits lower compressibility modulus relative to the segment without AuNP adsorption from multiple independent trajectories, as shown in SI Appendix, Table S6. This suggests that MPA-AuNP adsorption likely leads to local softening of the bilayer. Analysis of headgroup orientation and lipid tail order parameters (SI Appendix, Figs. S16 and S17) indicates that AuNP binding perturbs mainly the headgroup orientation, while having a minimal impact on the tails. The headgroups near the MPA-AuNP are better aligned with the membrane normal compared to those farther away; this leads to overall more repulsion between the neighboring headgroups, weakening the adhesion between neighboring lipids, which, in turn, leads to larger area fluctuations and thus a lower area compressibility modulus. On the other hand, as shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S18, a quantitative characterization of the area compressibility remains challenging even with microsecond MD trajectories; the statistical uncertainty associated with the computed area compressibility is about 12%, which is comparable to the difference between cases with and without the AuNP bound to the membrane. The subtle effect of AuNP binding on the membrane mechanical properties is not unexpected, since the DPhPC bilayer is stiff and the interaction between AuNP and the zwitterionic headgroup is relatively weak.

Discussion

Model membranes provide useful platforms to gain quantitative insight into interactions with nanoparticles such as binding, changes in lipid bilayer structure, and alterations to mechanical properties. While membrane modeling strategies are becoming increasingly sophisticated and computational modeling approaches have begun to complement experimental results, most studies investigating interactions with nanomaterials have been limited to single-component or mixed phospholipid bilayers, with only relatively few reports of models that incorporate other relevant membrane biomolecules (35, 36). The combined experimental and computational strategy taken in the present study allowed us to investigate the influence of nanoparticles binding on membrane properties and function.

The mechanosensitivity of gA ion channels arises from the dependence of gA dimerization on bilayer compressibility, meaning that its ion channel formation and the lifetime of channels depend on the ability of surrounding phospholipids to deform (62). The gA channels are smaller than the thickness of the phospholipid bilayer (46, 51, 63). Thus, gA dimerization and channel formation depends on the ability of the bilayer to compress to match the hydrophobic length (l = 2.6 nm) (64) of the channel (hydrophobic matching) (46, 55), a property important for larger ion channels (50, 65) and other membrane proteins (47).

Prior reports speculated that nanoparticles can indirectly alter ion channel function through interactions with the surrounding membrane (39, 42, 66), but experimental support for this has been inconclusive. For example, the reduction in sodium channel current amplitudes in neuroendocrine cells induced by exposure to silver nanoparticles was proposed to be mediated by changes in membrane mechanical properties (42). In another study, ZnO nanoparticles increased steady-state current amplitude, decreased the channel inactivation rate during steady-state depolarization, and had no effect on the current activation rate for HEK 239 cells. The mechanism was proposed to involve nanoparticle-induced alterations to channel gating (opening/closing) rather than channel blockage, but whether the effects observed were due to direct interaction of ZnO with the ion channel or indirect interactions with the lipid bilayer remained unresolved (39). The inconclusiveness of these studies reflects the challenges associated with measuring nanoparticle-induced alterations to the biophysical properties of the membranes of living cells.

Our results provide evidence that nanoparticles can indirectly disrupt the function of gA ion channels by altering mechanical properties of the surrounding lipid bilayer. Although similar results have not been reported for nanoparticles, several studies have investigated such effects using amphiphiles or drug molecules. For example, amphiphiles have been shown to change membrane properties such as compressibility and thickness, which alters channel function by modulating the energetic penalty for membrane deformation associated with the mismatch in hydrophobic thickness between the bilayer and embedded ion channel (46, 53, 67). The dependence of gA channel activity on bilayer hydrophobic matching has also been exploited to study the impact of drug molecules on bilayer stiffness by using gA as a “molecular force probe” to assess changes in bilayer properties such as bilayer compressibility (46, 52). The partitioning into or adsorption onto the membrane of these drug molecules alters bilayer stiffness, and, in turn, the bilayer disjoining force (Fdis) acting on gA channels, by changing the bilayer compression and bending moduli and intrinsic bilayer curvature (46). A decrease in bilayer stiffness and therefore in Fdis results in increases in N(t) and 𝜏, and an increase in bilayer stiffness has the opposite effect.

In our study, the malonate molecule chosen as our ligand control induced a decrease in channel lifetime, while differences in channel activity were not statistically significant. In contrast, anionic TCOOH- and MPA-AuNPs interact with the model membrane system containing gA in a manner that reduces the number of ion channels and extends the lifetime of remaining channels without changing conductance. Thus, whereas the effects of amphiphiles, peptides, and solvents result in coordinated changes in N(t) and 𝜏 (i.e., both properties change in the same direction), anionic AuNPs interacting with gA-containing bilayers cause N(t) and 𝜏 to change in opposite directions. This finding suggests more complex modulation of gA monomer–dimer kinetics in the case of interaction with anionic nanoparticles relative to partitioning or adsorption of molecular species. We note that the trends observed for small molecules may not extend to larger, flexible species like anionic polymers, which were previously reported to not exert an effect on gA (68).

Complementary evidence from our experimental and computational experiments also indicates that anionic AuNPs do not induce measurable changes in gA dimer structure or conformation within the lipid bilayer. First, FTIR characterization of amide I and II absorbances did not identify measurable changes that would indicate altered ion channel structure or conformation for gA-containing vesicles exposed to anionic AuNPs (57, 69, 70). Our FTIR results are also similar to previously reported effects for changes in amide absorbance for gA vesicles exposed to silver nanoparticles (58). Furthermore, MD simulations demonstrate that anionic TCOOH- and MPA-AuNPs do not interact strongly with gA ion channels or induce significant conformational changes to gA dimers. Rather, our computational results suggest that AuNP adsorption to the lipid bilayer surface induces local perturbation of the membrane and likely a concomitantly decreased compressibility modulus, which is consistent with the extended lifetimes of gA channels observed experimentally. Based on our combined results, we conclude that anionic AuNPs disrupt ion channel function by modulating local membrane properties rather than by direct nanoparticle−ion channel interactions.

Previous studies have reported that gA dimer configuration must stretch to a transition state before dissociating into monomers (71, 72). The thickness of the annular lipids is unable to match both dimer and the transition state; thus, hydrophobic mismatch is expected to affect the dissociation rate of the dimer. Since DPhPC and gA dimers exhibit significant hydrophobic mismatch (SI Appendix, Fig. S11), the formation of a gA dimer induces local lipid compression, and the degree of compression is less in the transition state. Decrease in compressibility modulus (thus bending modulus according to a polymer brush model for lipid mechanics) leads to a lower free energy penalty for lipid deformation and an increased barrier from the dimer to the transition state (73); the latter is consistent with the lifetime increase of the gA dimer observed experimentally. Similar effect on the gA dimer lifetime was reported for a series of amphiphiles, by Andersen and coworkers (53), who explained the increase of gA dimer lifetime in terms of reduced bilayer spring constant by the amphiphiles. Prior studies have reported that channel lifetimes and channel activity change in a concerted fashion with changes in bilayer mechanical properties. In contrast, anionic AuNPs induce changes in channel lifetime and activity that are inversely correlated, which, to the best of our knowledge, has not been previously described. Thus, the mechanisms of anionic AuNP modulation of gA ion channel activity cannot be described based solely on current understanding of the influence of membrane mechanics on channel activity. While further study will be required to understand the inverse correlation between lifetime and activity, our results point to the importance of developing more sophisticated modeling approaches to understand such effects.

Our combined experimental and computational results demonstrate that anionic AuNPs can indirectly alter gA ion channel function by changing local mechanical properties of the surrounding lipid bilayer. These findings also provide insight into the potential for nanoparticles to indirectly alter ion channel function in cells (39, 42, 66). Due to the complexity of such systems, determination of underlying mechanisms of interaction can be difficult, and attribution of ion channel disruption by nanoparticles to changes in membrane properties has been largely speculative in those system. For example, a role for changes in membrane mechanical properties has been proposed for the impact of silver nanoparticles on sodium channel function (42), and for the effect of ZnO nanoparticles on membrane potentials for HEK 239 cells (39). However, these studies could not distinguish between direct interactions with ion channels and indirect interactions with the surrounding lipid bilayer using available techniques (39, 42). While further investigation would be necessary to definitively correlate our results to biological outcomes, our combined approach establishes a connection between nanoparticle-induced modulation of membrane mechanical properties and impact on ion channel function and offers molecular-level insight into a possible underlying mechanism.

The ability of interactions with nanoparticles to impact the bilayer mechanical properties with concomitant effects on the hydrophobic matching of mechanosensitive ion channels has implications far beyond the present study. The activities of numerous membrane proteins are modulated by the coupling between hydrophobic protein domains and the bilayer core, including those of ion channels, transporters, receptors, and enzymes (47, 65). Our results indicate that nanoparticle effects on protein function do not require direct interaction; effects may also be mediated by changes in the biophysical properties of the lipid bilayer. Such indirect effects warrant investigation in evaluating the safety of engineered nanomaterials and suggest potential applications in modulating cellular function.

Materials and Methods

Details of all procedures can be found in SI Appendix.

Nanoparticle Synthesis and Characterization.

Gold nanoparticles with diameters of 2.1 ± 0.2 nm or 4.7 ± 1.3 nm were synthesized, functionalized with anionic ligands TCOOH or MPA, respectively, and characterized by TEM, ultraviolet visible spectroscopy, dynamic light scattering, and laser Doppler electrophoresis. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy was used to determine the number of ligands per MPA-AuNP.

Electrophysiology.

Electrophysiology measurements were performed on gA-containing DPhPC bilayers on a Planar Lipid Bilayer Workstation (Warner). Solution on both sides of the bilayer was 150 mM KCl buffered to pH 7.4 using 10 mM Hepes. A transmembrane potential of +50 mV was applied through silver wire electrodes connected to bath solutions by agar-filled glass U tubes. Nanoparticles of the indicated concentrations were added to either both sides or to only one side of the bilayer. The gA activity, lifetimes, and currents were observed over 7- to 10-min frames and quantified in 3.0- to 6.5-min frames, depending on channel densities per time (see SI Appendix for details).

ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy.

Infrared spectra were acquired from gA-containing DPhPC. Vesicles were formed via the vesicle extrusion method and were dropcast onto a single-bounce monolithic diamond internal reflection element (GladiATR, Pike Technologies). Triplicate spectra were collected with 300 scans and 2 cm−1 resolution. More information is available in SI Appendix.

MD Simulations.

MD simulations were performed on DPhPC and DMPC membranes with and without a single embedded gA dimer (Protein Data Bank ID code 1JNO) (74). A CHARMM36 (75–78) force field and membrane builder module of CHARMM-GUI (79–81) were used to generate the membrane and environment used in simulations. Each system was then incubated with a single MPA-AuNP. Replicates were performed at 100 ns each. Simulations have also been conducted for a single TCOOH-AuNP and for four MPA-AuNP aggregated together interacting with a DPhPC bilayer. Further detail is provided in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant CHE-2001611, the NSF Center for Sustainable Nanotechnology (CSN). The CSN is part of the Centers for Chemical Innovation Program. J.A.P. acknowledges support from the William A. Rothermel Bascom Professorship and the Vilas Distinguished Achievement Professorship. P.K. and X.Z. were supported by the National Institutes of Health under Award R01EB022641 for synthesis and characterization of TCOOH-AuNPs. We thank Paige Kinsley for assistance with the electrophysiology schematic.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2004736117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

All study data are included in the article and SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Tanzid M., et al. , Imaging through plasmonic nanoparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 5558–5563 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rastinehad A. R., et al. , Gold nanoshell-localized photothermal ablation of prostate tumors in a clinical pilot device study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 18590–18596 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy E. A., et al. , Nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery to tumor vasculature suppresses metastasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 9343–9348 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rejman J., Oberle V., Zuhorn I. S., Hoekstra D., Size-dependent internalization of particles via the pathways of clathrin- and caveolae-mediated endocytosis. Biochem. J. 377, 159–169 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang W., Kim B. Y. S., Rutka J. T., Chan W. C. W., Nanoparticle-mediated cellular response is size-dependent. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 145–150 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.dos Santos T., Varela J., Lynch I., Salvati A., Dawson K. A., Quantitative assessment of the comparative nanoparticle-uptake efficiency of a range of cell lines. Small 7, 3341–3349 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho E. C., Xie J., Wurm P. A., Xia Y., Understanding the role of surface charges in cellular adsorption versus internalization by selectively removing gold nanoparticles on the cell surface with a I2/KI etchant. Nano Lett. 9, 1080–1084 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shapero K., et al. , Time and space resolved uptake study of silica nanoparticles by human cells. Mol. Biosyst. 7, 371–378 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lesniak A., et al. , Nanoparticle adhesion to the cell membrane and its effect on nanoparticle uptake efficiency. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 1438–1444 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng Z. V., et al. , Impacts of gold nanoparticle charge and ligand type on surface binding and toxicity to Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Chem. Sci. (Camb.) 6, 5186–5196 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nazemidashtarjandi S., Farnoud A. M., Membrane outer leaflet is the primary regulator of membrane damage induced by silica nanoparticles in vesicles and erythrocytes. Environ. Sci. Nano 6, 1219–1232 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J., et al. , Cationic nanoparticles induce nanoscale disruption in living cell plasma membranes. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 11179–11185 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu W., et al. , Nanomechanical mechanism for lipid bilayer damage induced by carbon nanotubes confined in intracellular vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 12374–12379 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warren E. A. K., Payne C. K., Cellular binding of nanoparticles disrupts the membrane potential. RSC Adv. 5, 13660–13666 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dante S., et al. , Selective targeting of neurons with inorganic nanoparticles: Revealing the crucial role of nanoparticle surface charge. ACS Nano 11, 6630–6640 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hussain S., et al. , “Intracellular signal modulation by nanomaterials” in Nanomaterial: Impacts on Cell Biology and Medicine, Capco D. G., Chen Y., Eds. (Springer, 2014), pp. 111–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams D. N., et al. , Adverse interactions of luminescent semiconductor quantum dots with liposomes and Shewanella oneidensis. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 1, 4788–4800 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moghadam B. Y., Hou W.-C., Corredor C., Westerhoff P., Posner J. D., Role of nanoparticle surface functionality in the disruption of model cell membranes. Langmuir 28, 16318–16326 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang B., Zhang L., Bae S. C., Granick S., Nanoparticle-induced surface reconstruction of phospholipid membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 18171–18175 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laurencin M., Georgelin T., Malezieux B., Siaugue J. M., Ménager C., Interactions between giant unilamellar vesicles and charged core-shell magnetic nanoparticles. Langmuir 26, 16025–16030 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bailey C. M., et al. , Size dependence of gold nanoparticle interactions with a supported lipid bilayer: A QCM-D study. Biophys. Chem. 203–204, 51–61 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mensch A. C., Buchman J. T., Haynes C. L., Pedersen J. A., Hamers R. J., Quaternary amine-terminated quantum dots induce structural changes to supported lipid bilayers. Langmuir 34, 12369–12378 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Troiano J. M., et al. , Direct probes of 4 nm diameter gold nanoparticles interacting with supported lipid bilayers. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 534–546 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leroueil P. R., et al. , Wide varieties of cationic nanoparticles induce defects in supported lipid bilayers. Nano Lett. 8, 420–424 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harishchandra R. K., Saleem M., Galla H.-J., Nanoparticle interaction with model lung surfactant monolayers. J. R. Soc. Interface 7 (suppl. 1), S15–S26 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bothun G. D., Ganji N., Khan I. A., Xi A., Bobba C., Anionic and cationic silver nanoparticle binding restructures net-anionic PC/PG monolayers with saturated or unsaturated lipids. Langmuir 33, 353–360 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carney R. P., et al. , Electrical method to quantify nanoparticle interaction with lipid bilayers. ACS Nano 7, 932–942 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mensch A. C., et al. , Natural organic matter concentration impacts the interaction of functionalized diamond nanoparticles with model and actual bacterial membranes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 11075–11084 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodman C. M., McCusker C. D., Yilmaz T., Rotello V. M., Toxicity of gold nanoparticles functionalized with cationic and anionic side chains. Bioconjug. Chem. 15, 897–900 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao J., Zhang O., Ren J., Wu C., Zhao Y., Aromaticity/bulkiness of surface ligands to promote the interaction of anionic amphiphilic gold nanoparticles with lipid bilayers. Langmuir 32, 1601–1610 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Lehn R. C., et al. , Lipid tail protrusions mediate the insertion of nanoparticles into model cell membranes. Nat. Commun. 5, 4482 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Das M., Dahal U., Mesele O., Liang D., Cui Q., Molecular dynamics simulation of interaction between functionalized nanoparticles with lipid membranes: Analysis of coarse-grained models. J. Phys. Chem. B 123, 10547–10561 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y., et al. , Graphene microsheets enter cells through spontaneous membrane penetration at edge asperities and corner sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 12295–12300 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salis B., Pugliese G., Pellegrino T., Diaspro A., Dante S., Polymer coating and lipid phases regulate semiconductor nanorods’ interaction with neuronal membranes: A modeling approach. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 10, 618–627 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacobson K. H., et al. , Lipopolysaccharide density and structure govern the extent and distance of nanoparticle interaction with actual and model bacterial outer membranes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 10642–10650 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melby E. S., et al. , Peripheral membrane proteins facilitate nanoparticle binding at lipid bilayer interfaces. Langmuir 34, 10793–10805 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buchman J. T., et al. , Using an environmentally-relevant panel of Gram-negative bacteria to assess the toxicity of polyallylamine hydrochloride-wrapped gold nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Nano 5, 279–288 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gadsby D. C., Ion channels versus ion pumps: The principal difference, in principle. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 344–352 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piscopo S., Brown E. R., Zinc oxide nanoparticles and voltage-gated human Kv11.1 potassium channels interact through a novel mechanism. Small 14, e1703403 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leifert A., et al. , Differential hERG ion channel activity of ultrasmall gold nanoparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 8004–8009 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monticelli L., Barnoud J., Orlowski A., Vattulainen I., Interaction of C70 fullerene with the Kv1.2 potassium channel. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 12526–12533 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Busse M., et al. , Modeling the effects of nanoparticles on neuronal cells: From ionic channels to network dynamics. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2010, 3816–3819 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calvaresi M., Furini S., Domene C., Bottoni A., Zerbetto F., Blocking the passage: C60 geometrically clogs K+ channels. ACS Nano 9, 4827–4834 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gu Z., et al. , Exploring the nanotoxicology of MoS2: A study on the interaction of MoS2 nanoflakes and K+ channels. ACS Nano 12, 705–717 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kraszewski S., Tarek M., Treptow W., Ramseyer C., Affinity of C60 neat fullerenes with membrane proteins: A computational study on potassium channels. ACS Nano 4, 4158–4164 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lundbæk J. A., Collingwood S. A., Ingólfsson H. I., Kapoor R., Andersen O. S., Lipid bilayer regulation of membrane protein function: Gramicidin channels as molecular force probes. J. R. Soc. Interface 7, 373–395 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown M. F., Soft matter in lipid–protein interactions. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 46, 379–410 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kara S., et al. , Diphytanoyl lipids as model systems for studying membrane-active peptides. BBA–Biomembr. 1859, 1828–1837 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoo J., Cui Q., Three-dimensional stress field around a membrane protein: Atomistic and coarse-grained simulation analysis of gramicidin A. Biophys. J. 104, 117–127 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lundbæk J. A., Andersen O. S., Spring constants for channel-induced lipid bilayer deformations. Estimates using gramicidin channels. Biophys. J. 76, 889–895 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quist P. O., 13C solid-state NMR of gramicidin A in a lipid membrane. Biophys. J. 75, 2478–2488 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim T., et al. , Influence of hydrophobic mismatch on structures and dynamics of gramicidin A and lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 102, 1551–1560 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lundbæk J. A., Koeppe R. E. 2nd, Andersen O. S., Amphiphile regulation of ion channel function by changes in the bilayer spring constant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 15427–15430 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rasmussen A., et al. , The role of tryptophan residues in the function and stability of the mechanosensitive channel MscS from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 46, 10899–10908 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lundbæk J. A., Birn P., Girshman J., Hansen A. J., Andersen O. S., Membrane stiffness and channel function. Biochemistry 35, 3825–3830 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barth A., Zscherp C., What vibrations tell us about proteins. Q. Rev. Biophys. 35, 369–430 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sychev S. V., Barsukov L. I., Ivanov V. T., The double ππ5.6 helix of gramicidin A predominates in unsaturated lipid membranes. Eur. Biophys. J. 22, 279–288 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gambucci M., Gentili P. L., Sassi P., Latterini L., A multi-spectroscopic approach to investigate the interactions between Gramicidin A and silver nanoparticles. Soft Matter 15, 6571–6580 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Urry D. W., Shaw R. G., Trapane T. L., Prasad K. U., Infrared spectra of the gramicidin A transmembrane channel: The single-stranded-β 6-helix. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 114, 373–379 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hwang T. C., Koeppe R. E. 2nd, Andersen O. S., Genistein can modulate channel function by a phosphorylation-independent mechanism: Importance of hydrophobic mismatch and bilayer mechanics. Biochemistry 42, 13646–13658 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Feller S. E., Pastor R. W., Constant surface tension simulations of lipid bilayers: The sensitivity of surface areas and compressibilities. J. Chem. Phys. 111, 1281–1287 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sukharev S., Anishkin A., Mechanosensitive channels: What can we learn from ‘simple’ model systems? Trends Neurosci. 27, 345–351 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wallace B. A., Structure of gramicidin A. Biophys. J. 49, 295–306 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kelkar D. A., Chattopadhyay A., The gramicidin ion channel: A model membrane protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1768, 2011–2025 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Andersen O. S., Koeppe R. E. 2nd, Bilayer thickness and membrane protein function: An energetic perspective. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 36, 107–130 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yin S., et al. , Interactions of nanomaterials with ion channels and related mechanisms. Br. J. Pharmacol. 176, 3754–3774 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lundbæk J. A., et al. , Capsaicin regulates voltage-dependent sodium channels by altering lipid bilayer elasticity. Mol. Pharmacol. 68, 680–689 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Antonenko Y. N., Borisenko V., Melik-Nubarov N. S., Kotova E. A., Woolley G. A., Polyanions decelerate the kinetics of positively charged gramicidin channels as shown by sensitized photoinactivation. Biophys. J. 82, 1308–1318 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stevenson P., Tokmakoff A., Distinguishing gramicidin D conformers through two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy of vibrational excitons. J. Chem. Phys. 142, 212424 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sychev S. V., et al. , The solution conformations of gramicidin A and its analogs. Bioorg. Chem. 9, 121–151 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brannigan G., Brown F. L. H., A consistent model for thermal fluctuations and protein-induced deformations in lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 90, 1501–1520 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huang H. W., Deformation free energy of bilayer membrane and its effect on gramicidin channel lifetime. Biophys. J. 50, 1061–1070 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Venable R. M., Brown F. L. H., Pastor R. W., Mechanical properties of lipid bilayers from molecular dynamics simulation. Chem. Phys. Lipids 192, 60–74 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Townsley L. E., Tucker W. A., Sham S., Hinton J. F., Structures of gramicidins A, B, and C incorporated into sodium dodecyl sulfate micelles. Biochemistry 40, 11676–11686 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.MacKerell A. D., et al. , All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 3586–3616 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huang J., MacKerell A. D. Jr, CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: Validation based on comparison to NMR data. J. Comput. Chem. 34, 2135–2145 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Klauda J. B., et al. , Update of the CHARMM all-atom additive force field for lipids: Validation on six lipid types. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 7830–7843 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brooks B. R., et al. , CHARMM: The biomolecular simulation program. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 1545–1614 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jo S., Kim T., Iyer V. G., Im W., CHARMM-GUI: A web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 29, 1859–1865 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wu E. L., et al. , CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder toward realistic biological membrane simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 35, 1997–2004 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee J., et al. , CHARMM-GUI input generator for NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, and CHARMM/OpenMM simulations using the CHARMM36 additive force field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 12, 405–413 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and SI Appendix.