Abstract

The tumor suppressor p53 serves important roles in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, and its activation increases the sensitivity of cancer cells to radiotherapy or chemotherapy. In the present study, the small molecule 2-[1-(4-(benzyloxy)phenyl)-3-oxoisoindolin-2-yl)-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)] acetic acid (CDS-3078) significantly increased p53 mRNA expression levels in a dose-dependent manner. Treatment with CDS-3078 increased p53 expression levels and p53-mediated activation of its downstream target genes in HeLa cells. Additionally, p53+/+ HeLa cells treated with CDS-3078 presented with dysfunctional mitochondria, as indicated by the decrease in Bcl-2 levels, the increase in Bcl-2 homologous antagonist killer and the increase in cytochrome c release from the mitochondria to the cytoplasm. The present results suggested that CDS-3078 treatment significantly induced G2/M phase cell cycle arrest. Therefore, CDS-3078 administration induced apoptosis via p53-mediated cell cycle arrest, causing mitochondrial dysfunction and resulting in apoptotic cell death in cervical cancer cells. Collectively, the present results suggested that CDS-3078 may be a potential anticancer agent.

Keywords: small-molecule, G2/M arrest, apoptosis, HeLa cells, p53

Introduction

The tumor suppressor p53 has been identified as an important mediator of various cell signaling pathways, including proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, ferroptosis, DNA damage, DNA repair, senescence, autophagy, metabolism and angiogenesis (1,2). p53 functions as the guardian of the genome, not only in response to DNA damage, which is associated with tumor suppression, but also by inducing apoptosis in response to an altered cell cycle status, which is determined by the homeostasis of key proteins of various signaling pathways, including NF-κB and Bcl-2 family members (3). Since p53 is the most frequently mutated gene across various cancer types, such as breast carcinomas, brain cancers, sarcomas and adrenal cortical carcinomas (4), and is functionally inactive in ~50% of human tumors, it is considered as one of the most important tumor suppressor genes, being able to reduce the uncontrolled proliferation of cancer cells by promoting apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and chemosensitivity (5).

Apoptosis, a type of programmed cell death, is an important regulatory mechanism by which tumor cells die if DNA damage is not repaired (6). Additionally, apoptosis serves an important role in tissue development, homoeostasis and cancer cell death (7). During tumor development, cancer cells can develop unique mechanisms to evade the immune system, including increasing tolerance to apoptosis (8). Therefore, designing and identifying apoptosis-inducing agents is an effective therapeutic strategy in cancer research (9,10) and antitumor drugs may be identified by studying the apoptosis-inducing potential of these agents (11). The mechanisms of action underlying the apoptosis-induced potential of chemotherapeutic agents are involved in two major pathways; the death receptor-mediated pathway and the mitochondria-mediated pathway (12,13). Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-receptor (TRAIL)1 (also known as DR4), TRAIL2 (also known as DR5) and CD95, with their associated ligands, are responsible for the initiation of the death receptor-mediated apoptosis (14). Mitochondria-mediated apoptosis regulates the homeostatic balance between pro- and anti-apoptotic protein members, such as p53 and p53 downstream target factors, including p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA), phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate-induced protein 1 (Noxa) and Bcl-2 family members (15). A cascade of caspases is the final common convergence of the two pathways. Caspases cleave regulatory and structural factors, thus inducing apoptosis in tumor cells (16). Additionally, cell cycle arrest is frequently induced by p53 activation (17). The p53-mediated regulation of the cell cycle serves a central role in inhibiting tumor proliferation and progression (17). Accumulating evidence has suggested that factors regulated by p53 involved in the cell cycle and apoptosis represent alternative targets for cancer therapy and for the development of new targeting therapeutic agents (2,18-20).

Notably, 3-substituted-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindolin-1-one is a useful class of functional pharmacophore because they exert various biological activities, such as antihypertensive, antipsychotic, anesthetic, antiulcer, vasodilatory, antiviral, antileukemic, anxiolytic, antiasthma, anti-obesity, anti-ardiacangionosis and antitumor properties (21-27). In previous studies, cell-viability-based screening was performed using MTT assays in the 3-aryl isoindolinone ring library and the small molecule 2-[1-(4-(benzyloxy)phenyl)-3-oxoisoindolin-2-yl)-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)] acetic acid (CDS-3078) significantly increased the inhibitory ratio on HeLa cells (28,29). In the present study, CDS-3078 was found to significantly increase p53 transcriptional activity and induce apoptosis via the p53-mediated cell cycle arrest.

Materials and methods

Compounds and regents

The small organic molecule, CDS-3078, was synthesized by the Center for Combinatorial Chemistry and Drug Discovery of Jilin University, according to previous studies (28,29). DMSO-dissolved CDS-3078 was diluted in complete media for the following experiments performed in the present study. Antibodies targeting total caspase-3 (cat. no. sc-56053), caspase-8 (cat. no. sc-81656), caspase-9 (cat. no. sc-133109), poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP; cat. no. sc-56196), p53 (cat. no. sc-47698), p21 (cat. no. sc-71811), cytochrome c (cat. no. sc-13560), cyclin B1 (cat. no. sc-245), CDK1 (cat. no. sc-5319), checkpoint kinase (CHK) 1 (cat. no. sc-56288), CHK2 (cat. no. sc-136251), M-phase phosphatase 3 (CDC25C; cat. no. sc-327), phosphorylated (p)-ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein (ATR; cat. no. sc-515173), Bcl-2 (cat. no. sc-7382), Bcl-2 homologous antagonist killer (BAK; cat. no. sc-517390), BAX (cat. no. sc-7480), PUMA (cat. no. sc-374223), GAPDH (cat. no. sc-47724), β-actin (cat. no. sc-8432), goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (cat. no. sc-2005) and goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (cat. no. sc-2004) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Antibodies against p-CHK1 (cat. no. 12302) and p-CHK2 (cat. no. 2197) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Antibodies against the γ-histone 2A family, member X (H2AX; cat. no. ab26350) was from purchased from Abcam. PI, DAPI, MTT and other chemical reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA. The FITC-Annexin V Apoptosis Detection kit I was purchased from Bioteke Corporation. Caspase-3 (cat. no. BB-4106), Caspase-8 (cat. no. BB-4107) and Caspase-9 (cat. no. BB-4108) activity assay kits were obtained from Shanghai bestbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (www.bestbio.com.cn).

Cell cultures

Cervical cancer HeLa cells and human umbilical vein endothelium cells (HUVECs) were purchased from the Chinese Academy of Sciences Cell Bank. The cells were grown in DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS (Hyclone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences), 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin and 2 mM L-glutamine at 37˚C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

In vitro cell viability assays

Cell viability or cell growth inhibition of CDS-3078 was performed using an MTT assay. Briefly, HeLa cells (5x103 cells/well) were plated in a 96-well plate and incubated overnight. After removal of the media, the cells were treated with fresh DMEM or indicated concentrations (0.14, 0.37, 1.1, 3.3, 11, 33 or 100 µM) of CDS-3078 for 12, 24 and 48 h at 37˚C. After treatment, 20 µl of MTT (0.5 mg/well) solution was added and the plates were incubated for an additional 3 h at 37˚C. After removal of the culture media, 150 µl of DMSO was added to the culture wells to dissolve the resultant pellet. The quantity of formazan crystals that were an MTT redox product reduced by the mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase in living cells represented the number of living cells. The absorbance of formazan crystal at 495 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

Nuclear staining with DAPI

To observe the morphology changes, HeLa cells (5x104 cells/well) were seeded in a 24-well plate and incubated for 24 h at 37˚C. Subsequently, the cells were treated with DMEM (control) or 2 µM of CDS-3078 solution for 24 h at 37˚C. Finally, the cells were rinsed twice with PBS and stained with fresh media containing DAPI (2.5 µg/ml) for 5 min at room temperature. The morphology of the nuclei was determined using fluorescence microscopy.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

Total cell RNA was purified from HeLa cells using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and cDNA was prepared using cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Quantitative PCR was conducted using SYBR™-Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System according to the manufacturer's guidelines. The thermocycling conditions for real-time PCR were as follows: Denaturation at 95˚C for 15 sec, annealing at 60˚C for 20 sec and extension at 72˚C for 1 min, for 40 cycles. Specific primers pairs were used: p53 forward, 5'-CTGCCTTCCGGGTCACTGC-3' and reverse, 5'-TTGGGACGGCAAGGGGGACA-3'; p21 forward, 5'-GGAAGACCATGTGGACCTGT-3' and reverse, 5'-GGCGTTTGGAGTGGTAGAAA-3'; PUMA forward, 5'-TAGAGAGAGCGACGTGAC-3' and reverse, 5'-CGGTATCTACAGCAGCGCAT-3'; Noxa forwards, 5'-AGAGCTGGAAGTCGAGTGTG-3' and reverse, 5'-GGAGTCCCCTCATGCAAGTT-3'; and GAPDH forward, 5'-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3' and reverse, 5'-TCCACCACC-CTGTTGCTGTA-3'. The experiments were repeated ≥3 times, and mRNA expression levels were standardized by comparison to the transcript levels of the reference gene, GAPDH, based on the comparative threshold method (30).

Apoptosis and cell cycle analysis

Apoptosis assay was conducted using a FITC-Annexin V Apoptosis Detection kit (Bioteke Corporation) according to the manufacturer's protocol. In total, 3x105 cells were plated into a 6-well plate and incubated overnight at 37˚C. Subsequently, the cells were pretreated with fresh DMEM or different concentrations of CDS-3078 (2, 5 and 10 µM) for 24 h at 37˚C. After treatment, the cells were collected and washed three times with ice-cold PBS. The resultant cell pellets were incubated with 5 µl of FITC-conjugated Annexin V and 5 µl of propidium iodide (PI) for 15 min at room temperature. Fluorescence analysis was performed using a Beckman Flow Cytometry Analyzer (Beckman CytoFLEX; Beckman Coulter, Inc.). Cells were classified as early apoptotic (Annexin V-positive/PI-negative), late apoptotic/necrotic (Annexin V-positive/PI-positive), necrotic/dead (Annexin V-negative/PI-positive) and living cells (annexin-negative/PI-negative).

For cell cycle assays, the collected samples were fixed in 70% ice-cold ethanol overnight and washed twice in ice-cold PBS. The resultant cells were stained with in 100 µl PI solution (25 µg/ml RNase A, 50 µg/ml PI) and incubated at 37˚C for 30 min in the dark. The cell cycle distribution was examined using a Beckman Flow Cytometry Analyzer (Beckman CytoFLEX; Beckman Coulter, Inc.) analyzed using Flowjo 10.0.7 software (FlowJo LLC).

Western blotting analysis

After the indicated drug treatments, cell lysates were extracted using ice-cold lysis buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% NP-40 and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate] containing protease/phosphatase inhibitors [1% Cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA)] and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride at 4˚C for 10 min and protein was quantified using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Equal amounts of protein (40 µg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE (10% gel) and blotted to PVDF membranes (EMD Millipore). Subsequently, the membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBS supplemented with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with the aforementioned antibodies (dilution ratio, 1:200) overnight at 4˚C. Next, membranes were washed with TBST three times and incubated with the aforementioned peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (dilution ratio, 1:2,000) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, blots were visualized using the BeyoECL Star kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's protocol and GAPDH or β-actin were used as internal control. The relative density was determined using grayscale analysis on ImageJ v1.8.0_112 (National Institutes of Health) and normalized to GAPDH or β-actin.

Caspase activity assay

Caspase-3/8/9 activity assay was performed using caspase-3/8/9 activity kits by colorimetric assays, according to the manufacturer's protocol. After treating the cells for the indicated period, the cells were collected by centrifugation (10,000 x g, 10 min) at 4˚C. The resultant cell pellets were incubated in 100 µl of lysis buffer. The suspension was centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 10 min at 4˚C and an equal amount of supernatant was incubated with the corresponding substrates [Ac-DEVD-AFC (caspase-3), Ac-LETD-AFC (caspase-8), Ac-LEHD-AFC (caspase-9)] in the reaction buffer containing dithiothreitol at 37˚C for 10 min. The absorbance at 405 nm was examined using a microplate reader.

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Statistical differences were assessed using ANOVAs and post hoc test (Dunnett's test). SPSS 19.0 (IBM Corp.) was used for statistical analysis and P<0.05 represented a statistically significant difference.

Results

Inhibitory effects of CDS-3078 on HeLa cells

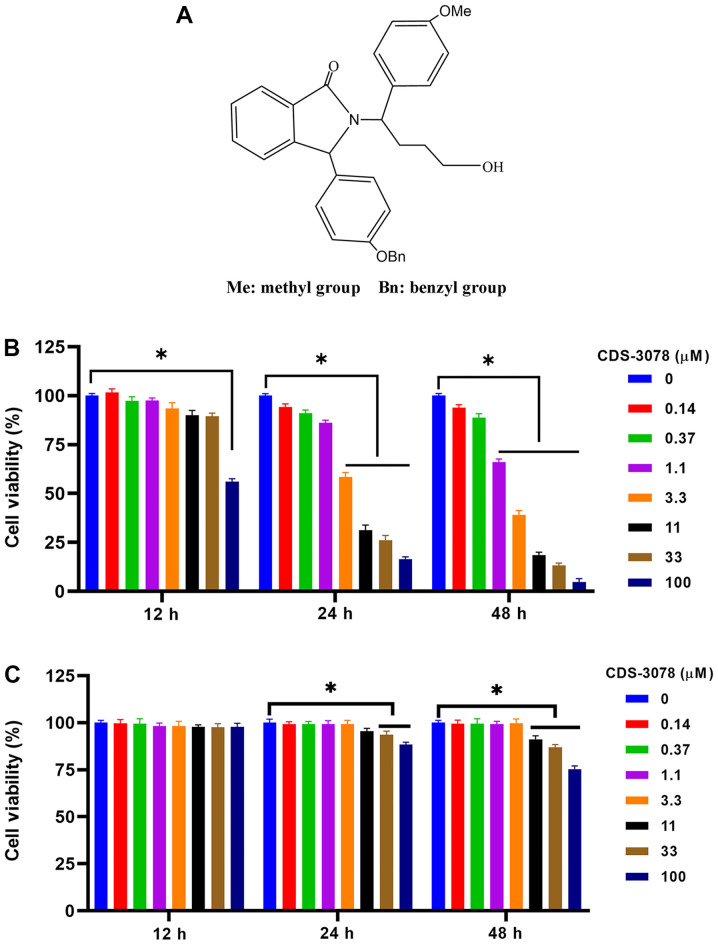

The heterocyclic alkaloid 2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindolin-1-one is widely found in natural products and has been shown to have a potential activity in cancer therapy by regulating cell cycle arrest or by inducing apoptosis in various cancer cells (31,32). Based on the anti-tumor effects of CDS-3078, the present study synthesized the small molecule (Fig. 1A). To confirm the inhibitory effects of CDS-3078 on HeLa and HUVEC cell proliferation, the cytotoxicity of CDS-3078 was analyzed using MTT assays. As shown in Fig. 1B, the inhibitory activity of CDS-3078 significantly increased in a concentration-dependent manner. The IC50 of CDS-3078 were 3.794 and 1.944 µM after 24 and 48 h, respectively. Moreover, CDS-3078 did not show an obvious proliferation inhibition on HUVECs (Fig. 1C). The present results suggested that CDS-3078 may be a potential anti-cancer agent.

Figure 1.

In vitro cytotoxic activity of CDS-3078 on the proliferation of human cervical cancer cells. (A) The chemical structure of CDS-3078. A total of 5x103 (B) HeLa and (C) HUVEC cells were seeded in a 96-well plate and then incubated with the designated concentration of CDS-3078 (0.14, 0.37, 1.1, 3.3, 11, 33 and 100 µM) for 12, 24 or 48 h. Cell viability was then determined using an MTT assay. *P<0.05 vs. control. CDS-3078, 2-[1-(4-(Benzyloxy)phenyl)-3-oxoisoindolin-2-yl)-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)] acetic acid.

CDS-3078 induces p53-dependent apoptotic cell death in human cervical cancer cells

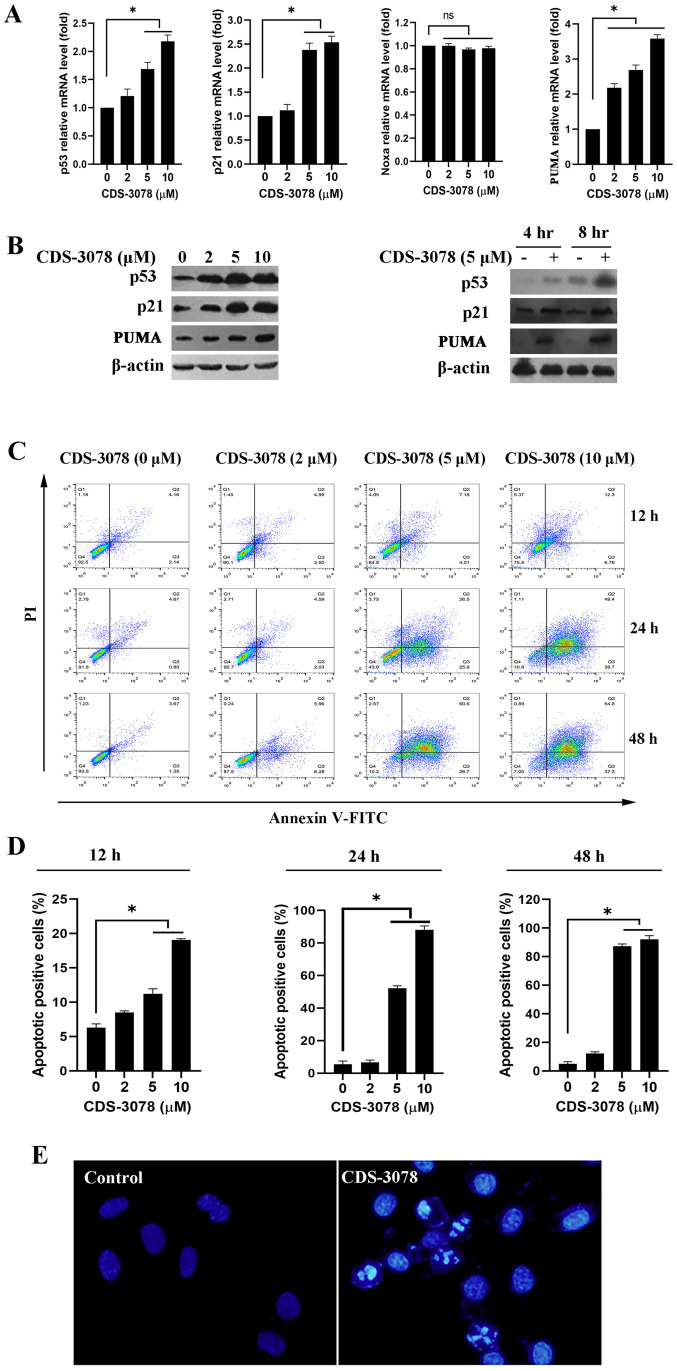

p53 is involved in the regulation of the proliferation of various cancer cells (16). In order to investigate whether the inhibitory effect of CDS-3078 on HeLa cells is through p53, the RNA and protein expression levels of p53 and its downstream factors were examined. As shown in Fig. 2A, the mRNA expression levels of p53, p21 and PUMA were significantly increased in a dose-dependent manner following CDS-3078 treatment (5 µM) in HeLa cells, whereas no changes in Noxa mRNA expression were detected. In line with these results, CDS-3078 treatment increased the protein expression levels p53 and p21 in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2B). It was then examined whether CDS-3078 could induce apoptotic cell death in p53+/+ HeLa cells. The apoptosis assay suggested that CDS-3078 treatment markedly induced accumulation of early apoptotic cells (Annexin V-positive and PI-negative) in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2C and D). The rates of early apoptotic cells were 5.52, 37.15 and 77.26% following a 24-h administration with CDS-3078 at 2, 5 and 10 µM, respectively. By contrast, the apoptotic rates were 7.81, 82.3 and 95.89% following a 48-h treatment with CDS-3078 at 2, 5 and 10 µM, respectively (Fig. 2D). Additionally, microscopic investigations indicated that 5 µM of CDS-3078 induced a series of morphological changes such as cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation (Fig. 2E). The present results suggested that CDS-3078 administration inhibited the proliferation and induced apoptotic cell death in HeLa cells.

Figure 2.

CDS-3078 enhances p53 transcriptional activity and protein expression, as well as inducing apoptotic death. (A) HeLa cells were treated with the specific concentrations of CDS-3078 (2, 5 and 10 µM) for 8 h and then the mRNA expression levels of p53, p21, Noxa and PUMA were determined using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. (B) HeLa cells were treated with indicated concentrations of CDS-3078 (2, 5 and 10 µM) for 24 h and then the protein expression levels of p53, p21 and PUMA were detected using western blotting. β-actin was used as a loading control. (C) HeLa cells were treated with different concentrations of CDS-3078 (2, 5 and 10 µM) for 12, 24 or 48 h. Subsequently, the apoptotic ratio was evaluated using flow cytometry. (D) Quantification of the percentage of early apoptotic HeLa cells following the various administration times. (E) Cells were treated with 5 µM of CDS-3078 for 24 h. The cells were fixed and stained with DAPI. The chromatin condensation and DNA fragmentation were then observed under a fluorescent microscope (magnification, x200) using a blue filter. *P<0.05 vs. vehicle control. CDS-3078, 2-[1-(4-(Benzyloxy)phenyl)-3-oxoisoindolin-2-yl)-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)] acetic acid; Noxa, phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate-induced protein 1; ns, not significant; PUMA, p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis.

CDS-3078 induces apoptosis involving members of the Bcl-2-family

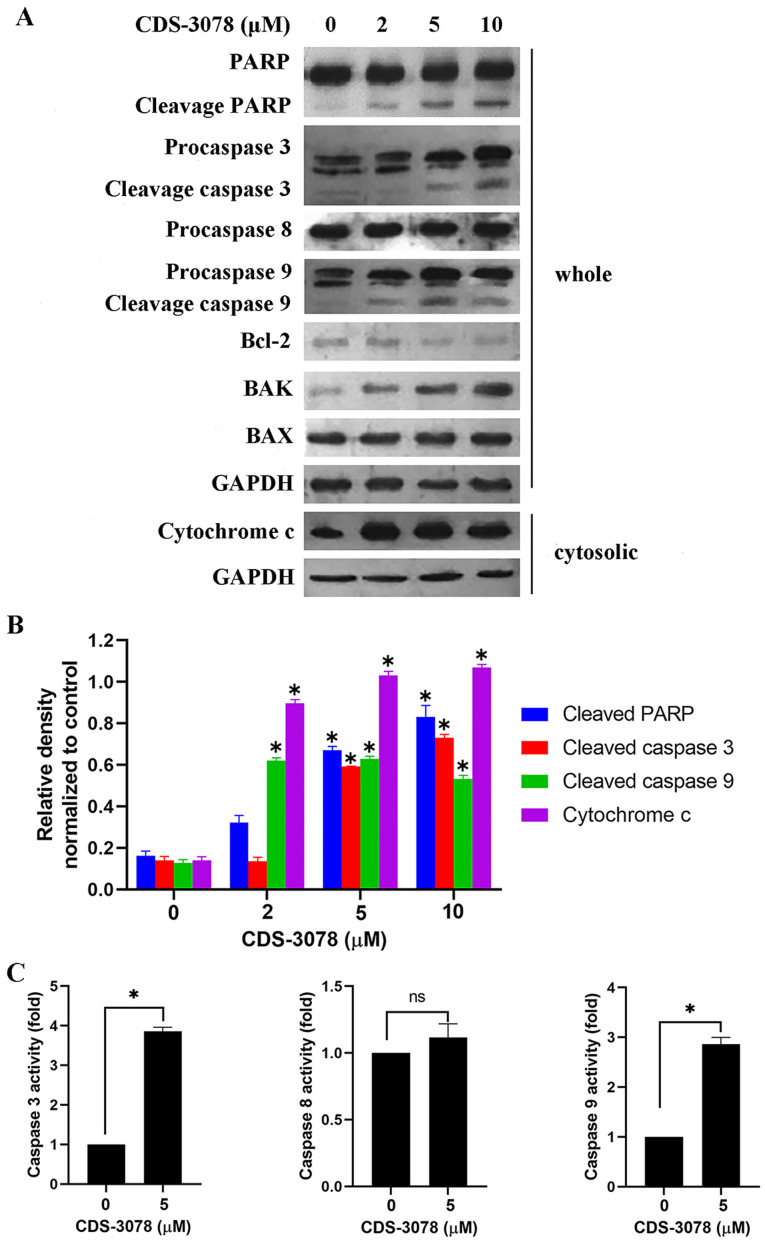

A previous study has demonstrated that p53-mediated apoptosis influences the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway (33). In this pathway, mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with the expression levels of Bcl-2-family members, thus causing apoptosis (34). The effects of CDS-3078 administration on the mitochondria-mediated apoptotic signaling pathway were therefore assessed in the present study. As shown in Fig. 3A and B, CDS-3078 treatment resulted in the proteolytic cleavage of pro-caspase-3, pro-caspase-9 and PARP, but did not induce changes in the expression levels of pro-caspase-8, indicating the activation of the mitochondria-mediated apoptosis pathway. In line with these results, CDS-3078 administration led to a 4-fold increase in caspase-3 and 2.7-fold increase in caspase-9 expression levels compared with respective negative controls; however, without affecting the expression levels of caspase-8 (Fig. 3C). Regarding the mitochondria-mediated pathway, CDS-3078 treatment resulted in a decrease in Bcl-2 and an increase in the pro-apoptotic BAK protein expression levels, but BAX protein expression levels were unaltered. Moreover, CDS-3078 induced the cytoplasmic release of cytochrome c in HeLa cells (Fig. 3A). Collectively, the present data showed that CDS-3078 administration downregulated Bcl-2 protein expression levels, but upregulated BAK expression and led to cytochrome c release by inducing disruption of the mitochondrial signaling pathway.

Figure 3.

CDS-3078 promotes mitochondria-mediated dysfunction and regulates the protein expression of Bcl-2 family. (A) Cells were treated with various concentrations of CDS-3078 (2, 5 and 10 µM) for 24 h, cytosolic extracts and whole-cell lysates were detected by immunoblotting to examine the expression levels of cytochrome c, Bcl-2, BAK, BAX, PARP and caspase-3/8/9. (B) The relative density was determined using grayscale analysis on ImageJ v 1.8.0_112 (National Institutes of Health), normalized to GAPDH. (C) Cells were treated with 5 µM CDS-3078 for 12 h. Equal amounts of cell lysates were analyzed for caspase-3, caspase-8 and caspase-9 activity using Ac-DEVD-AFC, Ac-LETD-AFC, Ac-LEHD-AFC as substrates, respectively. DMSO treatment was used as the control. The concentration of the fluorescent products released were then measured. Results represent the mean ± SD of three independent repeats. *P<0.05 vs. 0 µM CDS-3078 control. CDS-3078, 2-[1-(4-(Benzyloxy)phenyl)-3-oxoisoindolin-2-yl)-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)] acetic acid; PARP, poly ADP-ribose polymerase.

CDS-3078 induces cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase

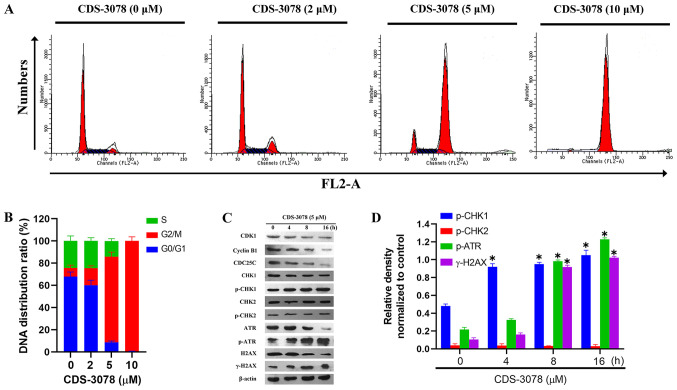

G2/M phase arrest in response to genotoxic stress is associated with the p53-p21 signaling pathway (17). To examine whether CDS-3078 was able to induce cell-cycle arrest, the DNA distribution ratio of CDS-3078-treated HeLa cells was investigated after 24 h of treatment using flow cytometry. CDS-3078 treatment increased the proportion of cells in the G2/M phase from 7.97±2.45% (control) to 15.44±2.11% (2 µM), 77.13±4.02% (5 µM) and 99.35±3.71% (10 µM) in HeLa cells (Fig. 4A and B). To further investigate the possible molecular mechanisms underlying G2/M-phase arrest in CDS-3078-induced HeLa cells, the expression levels of important regulators of cell cycle progression involved in G2/M phase arrest were investigated. The activation and/or deactivation of specific cyclin-CDK complexes regulate G2/M phase transition (35). The present results suggested that CDS-3078 administration decreased the expression levels of cyclin B1 in a time-dependent manner, decreased the expression levels of CDC25C and significantly upregulated the expression levels of p-CHK1 (Fig. 4C and D). By contrast, the protein expression levels of CHK2 and p-CHK2 were not significantly changed following CDS-3078 treatment in HeLa cells. The activation of CHK1 is involved in DNA damage (36); therefore, the expression levels of markers associated with DNA damage, including p-ATR and γ-H2AX were examined. As shown in Fig. 4C and D, CDS-3078 treatment increased the protein expression levels of γ-H2AX and p-ATR. Taken together, the present results suggested that CDS-3078 was involved in G2/M-phase arrest through the DNA-damage checkpoint cell signaling pathways.

Figure 4.

CDS-3078 induces cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase. (A) HeLa cells were pretreated with 2, 5 and 10 µM of CDS-3078 for 24 h, stained with PI and then subjected to DNA content analysis using flow cytometry. Data represents three independent repeats. (B) Quantification of the percentage of G0/G1, S and G2/M HeLa cells at the various administration times. (C) HeLa cells were treated with CDS-3078 (5 µM) for 4, 8 and 16 h. The expression levels of the proteins associated with the cell cycle were examined using immunoblotting to detect expression levels of CDK1, cyclin B1, CDC25C, CHK1, p-CHK1, CHK2, p-CHK2, ATR, p-ATR, H2AX and γ-H2AX. (D) The relative density was determined using grayscale analysis on ImageJ 1.8.0_112 (National Institutes of Health) normalized to corresponding non-phosphorylated total protein. CDS-3078, 2-[1-(4-(Benzyloxy)phenyl)-3-oxoisoindolin-2-yl)-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)acetic acid; CHK, checkpoint kinase; CDC25C, M-phase phosphatase 3; H2AX, H2A histone family, member X; ATR, ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein; p-, phosphorylated. *P<0.05 vs. control.

Discussion

In the present study, a small-molecule anticancer agent was identified from a 3-aryl isoindolinone ring library using a cell viability assay. CDS-3078, a 3-substituted-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindolin-1-one derivate, was identified as a p53-activating agent with potential proliferation inhibitory-effects against tumor cells.

It is well documented that p53 is a widely accepted cancer driver gene, making it a valuable target for anticancer therapy (1). After 40 years of research focused on p53, the United States Food and Drug Administration approved various p53-specific therapies, including gene therapy. However, various p53-targeted therapeutic strategies, including the interaction between p53 and Mouse double minute 2 homolog (MDM2), as well as the pharmacological restoration of mutant p53, require further investigation (37,38).

The present study suggested that CDS-3078 upregulated the mRNA and protein expression levels of p53 and p53-target genes. In addition, p21 serves a key role in cell cycle arrest following DNA damage by inhibiting either CDK activity or the formation of the cyclin B1-CDK1 complex (39). The expression levels of PUMA, a key effector of p53-mediated apoptosis (40), was found to be upregulated in the present study. It was hypothesized that p53- and p53-targeting factors-mediated signaling pathways may serve important roles in inducing G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. The present results suggested that CDS-3078 administration inhibited cell proliferation and induced apoptosis in p53+/+ HeLa cells. Moreover, mitochondrial membrane impairment caused by CDS-3078 administration is considered a sign of early apoptosis (41); however, the potential of this small molecule to affect the mitochondrial membrane requires further verification. Notably, the drug safety and application potential of CDS-3078 requires further verification in various cancer cells types and in vivo experiments.

The activation of cell cycle checkpoint-related proteins, inducing cell cycle arrest, allows DNA repair in response to DNA damage. G2/M checkpoints are more sensitive to chemotherapeutic or radiotherapeutic agents compared with G1 checkpoints (42,43). CHK1 and CHK2, effectors of DNA damage checkpoints, serve a central role in inducing cell cycle arrest and DNA repair in response to DNA damage (44). The present results suggested that CDS-3078 treatment induced a concentration-dependent increase in cells arrested at the G2 phase due to the decrease in the expression levels of cyclin B1, CDK1 and CDC25C. As an important kinase associated with CDC25C regulation, phosphorylation levels of CHK1 were found to be increased after CDS-3078 administration, indicating the activation of CHK1(45). Although CHK1 and CHK2 are functionally associated, no changes in the phosphorylation and protein expression levels of CHK2 were identified in CDS-3078-treated HeLa cells. CDS-3078 treatment also increased the expression levels of ATR and γ-H2AX, which are involved in the transduction of early signals following DNA double-strand breaks in response to cytotoxic stresses (46). The present results suggested that CDS-3078 induced p53-mediated apoptotic cell death through G2/M phase arrest.

Apoptosis can be induced by various stimuli and is mediated by two signaling pathways: The intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. These pathways are involved in the activation of various effectors and the release of proapoptotic mediators from mitochondria (47). In the present study, CDS-3078 treatment resulted in apoptosis via the proteolytic cleavage of caspase-3 and PARP; downregulation of Bcl-2; upregulation of BAK; and release of cytochrome c. Based on these data, it was speculated that CDS-3078 served as a potential small molecule inhibitor through the caspase-dependent mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in HeLa cells.

In conclusion, the present results suggested that the small molecule CDS-3078 exhibited a potential cytotoxic effect on human cervical cancer cells. Furthermore, CDS-3078 administration triggered mitochondria-mediated apoptotic cell death and G2/M-phase cell cycle arrest in the p53+/+ HeLa cells. Therefore, the present results suggested that CDS-3078 may be a potential chemotherapeutic candidate to be evaluated in clinical settings for the treatment of cervical cancer.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from the Foundation of Education Department of Jilin Province (grant no. 2016133), the Special Foundation for Industry Innovation of Development and Reform Commission of Jilin (grant no. 2018C049-4), the Youth Foundation of Jilin Science and Technology Bureau (grant nos. 20166026 and 201750259) and the Major Programs of the Jilin Institute of Chemical Technology (grant no. 20180101).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

YZ, XB, and WS conceived the experiments. YZ, JR, YG, PL and CH conducted the experiments. YZ, WS produced the manuscript and performed result analysis. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Sabapathy K, Lane DP. Therapeutic targeting of p53: All mutants are equal, but some mutants are more equal than others. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:13–30. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bykov VJN, Eriksson SE, Bianchi J, Wiman KG. Targeting mutant p53 for efficient cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18:89–102. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oren M. Decision making by p53: Life, death and cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:431–442. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olivier M, Hollstein M, Hainaut P. TP53 mutations in human cancers: Origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(a001008) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryu H, Nam KY, Kim JS, Hwang SG, Song JY, Ahn J. The small molecule AU14022 promotes colorectal cancer cell death via p53-mediated G2/M-phase arrest and mitochondria-mediated apoptosis. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:4666–4676. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su ZY, Yang ZZ, Xu YQ, Chen YB, Yu Q. Apoptosis, autophagy, necroptosis, and cancer metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:48–61. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0321-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elmore S. Apoptosis: A review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bremer E, van Dam G, Kroesen BJ, de Leij L, Helfrich W. Targeted induction of apoptosis for cancer therapy: Current progress and prospects. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:382–393. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makin G, Hickman JA. Apoptosis and cancer chemotherapy. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;301:143–152. doi: 10.1007/s004419900160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sellers WR, Fisher DE. Apoptosis and cancer drug targeting. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1655–1661. doi: 10.1172/JCI9053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan ST, Li ZL, He ZX, Qiu JX, Zhou SF. Molecular mechanisms for tumour resistance to chemotherapy. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2016;43:723–737. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ichim G, Tait SW. A fate worse than death: Apoptosis as an oncogenic process. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:539–548. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koff JL, Ramachandiran S, Bernal-Mizrachi L. A time to kill: Targeting apoptosis in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:2942–2955. doi: 10.3390/ijms16022942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Von Karstedt S, Montinaro A, Walczak H. Exploring the TRAILs less travelled: TRAIL in cancer biology and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:352–366. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aubrey BJ, Kelly GL, Janic A, Herold MJ, Strasser A. How does p53 induce apoptosis and how does this relate to p53-mediated tumour suppression? Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:104–113. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh R, Letai A, Sarosiek K. Regulation of apoptosis in health and disease: The balancing act of BCL-2 family proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:175–193. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0089-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen JD. The cell-cycle arrest and apoptotic functions of p53 in tumor initiation and progression. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6(a026104) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stegh AH. Targeting the p53 signaling pathway in cancer therapy-the promises, challenges, and perils. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;16:67–83. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.643299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prabhu VV, Allen JE, Hong B, Zhang SL, Cheng HR, EI-Deiry WS. Therapeutic targeting of the p53 pathway in cancer stem cells. Expert Opin Ther Targest. 2012;16:1161–1174. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2012.726985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joana DA, Joana MX, Clifford JS, Cecília MP. Targeting the p53 pathway of apoptosis. Curr Pharm Design. 2010;16:2493–2503. doi: 10.2174/138161210791959818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belliotti TR, Brink WA, Kesten SR, Rubin JR, Wustrow DJ, Zoski KT, Whetzel SZ, Corbin AE, Pugsley TA, Heffner TG, Wise LD. Isoindolinone enantiomers having affinity for the dopamine D4 receptor. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1998;8:1499–1502. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00252-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhuang ZP, Kung MP, Mu M, Kung HF. Isoindol-1-one Analogues of 4-(2-methoxyphenyl)-1-[2-[N-(2-pyridyl)-p-iodobenzamido] ethyl] piperazine (p-MPPI) as 5-HT1A receptor ligands. J Med Chem. 1998;41:157–166. doi: 10.1021/jm970296s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanamitsu N, Osaki T, Itsuji Y, Yoshimura M, Tsujimoto H, Soga M. Novel water-soluble sedative-hypnotic agents: Isoindolin-1-one derivatives. Chem Pharm Bull. 2007;55:1682–1688. doi: 10.1248/cpb.55.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernstein PR, Aharony D, Albert JS, Andisik D, Barthlow HG, Bialecki R, Davenport T, Dedinas RF, Dembofsky BT, Koether G, et al. Discovery of novel, orally active dual NK1/NK2 antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2001;11:2769–2773. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00572-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wacker DA, Varnes JG, Malmstrom SE, Cao X, Hung CP, Ung T, Wu G, Zhang G, Zuvich E, Thomas MA, et al. Discovery of (R)-9-Ethyl-1,3,4,10b-tetrahydro-7-trifluoromethylpyrazino[2,1-a]isoindol-6(2H)-one, a selective, orally active agonist of the 5-HT(2C) receptor. J Med Chem. 2007;50:1365–1379. doi: 10.1021/jm0612968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pendrak I, Barney S, Wittrock R, Lambert DM, Kingsbury WD. Synthesis and anti-HSV activity of a-ring-deleted mappicine ketone analog. J Org Chem. 1994;59:2623–2625. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor EC, Zhou P, Jennings LD, Mao Hu ZB, Jun JG. Novel synthesis of a conformationally-constrained analog of DDATHF. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:521–524. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu CM, Zheng LY, Pei YZ, Bai X. Synthesis of novel 3-aryl isoindolinone derivatives. Chem Res Chin Univ. 2013;29:487–494. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu CM. Design, synthesis and anticancer activity of novel 3-aryl isoindolinone derivatives. Changchun Jilin University, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valente LJ, Aubrey BJ, Herold MJ, Kelly GL, Happo L, Scott CL, Newbold A, Johnstone RW, Huang DC, Vassilev LT, Strasser A. Therapeutic response to non-genotoxic activation of p53 by Nutlin3a Is driven by PUMA-mediated apoptosis in lymphoma cells. Cell Rep. 2016;14:1858–1866. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shah JH, Swartz GM, Papathanassiu AE, Treston AM, Fogler WE, Madsen JW, Green SJ. Synthesis and enantiomeric separation of 2-phthalimidino-glutaric acid analogues: Potent inhibitors of tumor metastasis. J Med Chem. 1999;42:3014–3017. doi: 10.1021/jm990083y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardcastle IR, Liu J, Valeur E, Watson A, Ahmed SU, Blackburn TJ, Bennaceur K, Clegg W, Drummond C, Endicott JA, et al. Isoindolinone inhibitors of the murine double minute 2 (MDM2)-p53 protein-protein interaction: Structure-activity studies leading to improved potency. J Med Chem. 2011;54:1233–1243. doi: 10.1021/jm1011929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yin C, Knudson CM, Korsmeyer SJ, Van Dyke T. Bax suppresses tumorigenesis and stimulates apoptosis in vivo. Nature. 1997;385:637–640. doi: 10.1038/385637a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Czabotar PE, Lessene G, Strasser A, Adams JM. Control of apoptosis by the BCL-2 protein family: Implications for physiology and therapy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:49–63. doi: 10.1038/nrm3722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DiPaola RS. To arrest or not to G2-M cell-cycle arrest. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3311–3314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yarden RI, Pardo-Reoyo S, Sgagias M, Cowan KH, Brody C. BRCA1 regulates the G2/M checkpoint by activating Chk1 kinase upon DNA damage. Nat Genet. 2002;30:285–289. doi: 10.1038/ng837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang WS, Hu YZ. Small molecule agents targeting the p53-MDM2 pathway for cancer therapy. Med Res Rev. 2012;32:1159–1196. doi: 10.1002/med.20236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao DK, Tahaney WM, Mazumdar A, Savage MI, Brown PH. Molecularly targeted therapies for p53-mutant cancers. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74:4171–4187. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2575-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deng CX, Zhang PM, Harper JW, Elledge SJ, Leder P. Mice lacking p21CIP1/WAF1 undergo normal development, but are defective in G1 checkpoint control. Cell. 1995;82:675–684. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor RC, Cullen SP, Martin SJ. Apoptosis: Controlled demolition at the cellular level. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:231–241. doi: 10.1038/nrm2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang CX, Youle RJ. The role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:95–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su TT. Cellular responses to DNA damage: One signal, multiple choices. Annu Rev Genet. 2006;40:187–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bucher N, Britten CD. G2 checkpoint abrogation and checkpoint kinase-1 targeting in the treatment of cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:523–528. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith J, Tho LM, Xu N, Gillespie DA. The ATM-Chk2 and ATR-Chk1 pathways in DNA damage signaling and cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2010;108:73–112. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380888-2.00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sur S, Agrawal DK. Phosphatases and kinases regulating CDC25 activity in the cell cycle: Clinical implications of CDC25 overexpression and potential treatment strategies. Mol Cell Biochem. 2016;416:33–46. doi: 10.1007/s11010-016-2693-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mah LJ, El-Osta A, Karagiannis TC. gammaH2AX: A sensitive molecular marker of DNA damage and repair. Leukemia. 2010;24:679–686. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ola MS, Nawaz M, Ahsan H. Role of Bcl-2 family proteins and caspases in the regulation of apoptosis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;351:41–58. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0709-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.