Abstract

Measurement of cytokine gene expression by reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) is used widely to assess the immune system of animals and to identify biomarkers of disease, but its application is limited in wildlife species due to a lack of species-specific reagents. The free-ranging endangered Australian sea lion (Neophoca cinerea) experiences significant clinical disease and high pup mortality due to intestinal hookworm infection. Developing immunological tools specific to the species will aid in the assessment of drivers of disease and its impact in population demographics. This study describes the development and validation of cross-reactive RT-qPCR assays to measure five important cytokines involved in innate and Th1/Th2 responses (IL-6, TNFα, IFNγ, IL-4 and IL-10) in unstimulated blood samples from a range of different mammalian species including the Australian sea lion. All RT-qPCR assays efficiencies ranged between 87% (Ovis aries TNFα) and 111% (Bos taurus IL-10) and had strong linearity (R2). IL-4 and IFNγ gene expression for N. cinerea fell below the dynamic range (and therefore quantifiable limits) of RT-qPCR assays but were able to be quantified using the novel droplet digital PCR (ddPCR). This study delivers new immunological tools for eco-immunologists studying cytokine gene expression in wildlife species and is to our knowledge, the first cytokine ddPCR approach to be reported in a pinniped species.

Keywords: RT-qPCR, ddPCR, Cytokine, Immune response, Neophoca cinerea, Interleukin, Cross-reactive, Gene expression, Ecoimmunology, Pinniped

Introduction

Wildlife species are exposed to a wide range of stressors, often increasing their susceptibility to disease. The endangered Australian sea lion (Neophoca cinerea) experiences high pup mortality rates at some colonies in southern Australia, limiting population growth and likely contributing to population decline (Goldsworthy, 2015; Goldsworthy et al., 2009; Marcus, Higgins & Gray, 2014; Shaughnessy et al., 2011). Disease caused by hookworms (Uncinaria sanguinis) has been identified as a significant contributor to this trend (Marcus, Higgins & Gray, 2014). Given this endemic pathogen is prevalent at 100% in pups, an understanding of the host response is likely to be informative when evaluating the potential for factors such as anthropogenic pollution, resource or genetic limitations to impact susceptibility to disease. In every species, disease outcomes result, in part, from the interaction between multiple immune cell types and specialised secretory molecules such as acute phase proteins, hormones and cytokines that work together as a network in up-regulated and down-regulated pathways. Cytokines play an essential role in both the initiation and maintenance of the immune response against pathogens, and their variations serve as indicators to assess the immune system of animals and as biomarkers of disease (Fonfara et al., 2008; Fonfara, Siebert & Prange, 2007; Murtaugh et al., 1996; Sitt et al., 2016). Wildlife researchers within the growing discipline of eco-immunology, are using approaches such as the reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) to measure the expression of cytokine messenger RNA (mRNA) in order to understand the immune system in a wild context (Bowen et al., 2006; Bowen et al., 2012; Brock, Murdock & Martin, 2014; Shoda, Brown & Rice-Ficht, 1998). Although some progress has been made, further research is needed to evaluate the impacts of threats on individual fitness and species resilience (Bowen et al., 2012; Puech et al., 2015; Spitz et al., 2015), so as to guide management decisions aimed toward protecting threatened populations.

Many RT-qPCR protocols have been developed to characterise cytokine gene expression in mice, humans and domestic animals owing to the availability of complete genomic sequences for those species (Boeuf et al., 2005; Murtaugh et al., 1996; Overbergh et al., 1999). However, specific or cross-reactive reagents for threatened wildlife species are still limited (Levin, 2018; Zimmerman et al., 2014). For marine mammals, mRNA expression of cytokines interleukin (IL)-4, IL-10 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α have been examined in cetaceans (Beineke et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2016; Fair et al., 2017; Funke et al., 2002; Inoue et al., 1999; King et al., 1996; Lehnert et al., 2019; St-Laurent, Béliveau & Archambault, 1999). IL-2, IL-10 and, less commonly IL-4, IL-6 and interferon (IFN)-γ have been studied in pinnipeds (Fonfara et al., 2008; Funke et al., 2002; Levin et al., 2014; Shoda, Brown & Rice-Ficht, 1998). These commonly studied cytokines play key roles in orchestrating the balance between critical innate (IL-6, TNFα), T-helper-1 (Th1: IFNγ), T-helper-2 (Th2: IL-4) and T-regulatory (IL-10) immunological pathways. These pathways are interdependent, requiring a finely controlled balance for a productive response, and some overlap in function between resulting immune pathways can occur (Del Prete et al., 1993). In marine mammals, as in other mammals, inflammation is initiated and maintained by signals (e.g. IL-6, TNFα) from sentinel cells of the innate response. Subsequent adaptive responses may focus on Th1 responses (IFNγ) for clearance of intracellular organisms (Fair et al., 2017; Ferrante, Hunter & Wellehan, 2018; Fonfara et al., 2008). Typically, the differentiation of Th2 lymphocytes shifts immunity into a humoral response to combat extracellular pathogens, including parasites (Abo-Aziza et al., 2020; Rostami-Rad, Jafari & Yousofi Darani, 2018). Cytokine IL-4, secreted by Th2 cells, promotes the maturation of B lymphocytes towards plasma cells and immunoglobulin secretion for antibody-mediated responses, long term immunity and repair. This Th2 response is also facilitated by IL-10 which preferentially supresses Th1 responses (Fair et al., 2017; Fonfara et al., 2008).

The majority of cytokine gene expression studies in pinnipeds have been in phocids or involved stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PMBC) (Das et al., 2008; Fonfara et al., 2008; Levin, 2018). The remote locations and challenging logistics associated with sampling the Australian sea lion and many other wildlife species generally precludes cell separation and culture methods and rather requires the use of whole blood stored in RNA preservative. RT-qPCR is the gold standard for relative gene expression and has become widely used in wildlife (Bowen et al., 2012; Bustin et al., 2005; Funke et al., 2002; Lau et al., 2015; Lehnert et al., 2019) but is limited when applied to samples with low gene transcript concentrations and/or the presence of PCR inhibitors. The more recently developed droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) has potential to overcome these limitations by partitioning a normal PCR reaction into thousands of droplets, in which fluorescent dye-based end-point PCRs occur independently, thereby increasing the likelihood of detecting low abundance targets by decreasing the effect of interfering substances and PCR biases (Rački et al., 2014). These features can allow for more precise, reproducible and statistically significant results when working with low levels of nucleic acid and variable amounts of contaminants (Baker et al., 2018; Hindson et al., 2013; Rački et al., 2014; Taylor, Laperriere & Germain, 2017) but the technique has not yet been widely applied in immunology studies of free-ranging animals.

The purpose of this study is to develop and validate RT-qPCR assays to measure, by relative quantification via the delta Ct method, five important cytokines involved in innate and Th1/Th2 responses (IL-6, TNFα, IFNγ, IL-4 and IL-10) in the Australian sea lion. A consensus sequence approach was taken, and the primers’ performance in diverse domestic species was confirmed to illustrate their suitability as candidates for evaluation in future immunological studies of other mammalian wildlife species. Additionally, a subset of these primers was adapted for use in species-specific ddPCR to permit quantification of IL-4 and IFNγ mRNA, which were found to be in low-abundance in blood samples collected from Australian sea lion pups.

Materials and Methods

Real-time PCR primer design

Sequences for genes of interest (GOI) IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IFNγ and TNFα of multiple mammal species were obtained from Genbank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank) and aligned (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of consensus primers (IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IFNγ and TNFα) developed for Neophoca cinerea, Canis familiaris, Bos taurus, and Ovis aries in the study, and GAPDH (Peters et al., 2004) reference gene primers used in the study.

| Gene | GenBank ensemble sequences | Primers (5′->3′) (based on ** marked sequences) | Annealing/extension (°C, s) | Amplicon size (bp) | Conc (nM) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-4 | **AF083270.1_Canis familiaris | IL-4 F: TCACCTCCCAACTGATTCCAA | 60 °C, 30 | 135 | 200 | 82 |

| EU276069.1_Bos taurus | ||||||

| NM_001304911.1_Ailuropoda melanoleuca | ||||||

| KP792599.1_Neovison vison | ||||||

| XM_027606287.1_Zalophus californianus | IL-4 R: ACGAGTCGTTTCTCGCTGTG | 60 °C, 30 | ||||

| XM_006734683.1_Leptonychotes weddellii | ||||||

| AB020732.1_Tursiops truncatus | ||||||

| HM011505.1_Macropus eugenii | ||||||

| IL-6 | **L46802.1_Phoca vitulina | IL-6 F: CTGCTCCTGGTGATGGCTAC | 60 °C, 30 | 147 | 200 | 84.5 |

| U64794.1_Equus caballus | ||||||

| AF275796.1_Canis familiaris | ||||||

| EF368209.1_Mustela putorius furo | IL-6 R: TGCAGAGATTTTGCCGAGGA | 60 °C, 30 | ||||

| EF543744.1_Ailuropoda melanoleuca | ||||||

| L46803.1_Orcinus orca | ||||||

| IFNγ | **KJ888148.1_Neovison vison | IFNγ F: GTGAATGATCTGCAGGTCCA | 60 °C, 30 | 101 | 200 | 80 |

| NM_213948.1_Sus scrofa | ||||||

| NM_001003174.1_Canis familiaris | ||||||

| XM_026500086.1_Ursus arctos | ||||||

| XM_027593881.1_Zalophus californianus | IFNγ R: TGACTCCTTTTCCGCTTCCT | 60 °C, 30 | ||||

| XM_025883084.1_Callorhinus ursinus | ||||||

| XM_006740002.1_Leptonychotes weddellii | ||||||

| DQ118388.1_Phoca vitulina | ||||||

| IL-10 | **NM_001003077.1_Canis familiaris | IL-10 F: CTTTAAGAGTTACCTGGGTTGCC | 60 °C, 30 | 97 | 200 | 83.5 |

| DQ890062.1_Macaca mulatta | ||||||

| NM_001082490.1_Equus caballus | ||||||

| XM_002919274.3_Ailuropoda melanoleuca | ||||||

| XM_027613593.1_Zalophus californianus | IL-10 R: GATGTCTGGGTCGTGGTTCTC | 60 °C, 30 | ||||

| XM_004417581.2_Odobenus rosmarus | ||||||

| L46802.1_Phoca vitulina | ||||||

| AF026277.1_Trichosurus vulpecula | ||||||

| TNFα | **XM_027099307_Lagenorhynchus obliquidens | TNFα F: GAGCACTGAAAGCATGATCCG | 60 °C, 30 | 123 | 200 | 87 |

| D86587.1_Capra hircus | ||||||

| NM_001003244.4_Canis familiaris | ||||||

| EF368211.1_Mustela putorius furo | ||||||

| XM_002930032.3_Ailuropoda melanoleuca | TNFα R: GCGACCAGGAAGAAGGAGAA | 60 °C, 30 | ||||

| XM_027603858.1_Zalophus californianus | ||||||

| XM_025862490.1_Callorhinus ursinus | ||||||

| XM_006738478.1_Leptonychotes weddellii | ||||||

| GAPDH | Peters et al. (2004) | GAPDH F: TCAACGGATTTGGCCGTATTGG | 60 °C, 30 | 90 | 400 | 83.5 |

| GAPDH R: TGAAGGGGTCATTGATGGCG |

Notes:

Tm, melting temperature.

Marked sequences: IL-4 AF083270.1_Canis familiaris; IL-6 L46802.1_Phoca vitulina; IFNγ KJ888148.1_Neovison vison; IL-10 NM_001003077.1_Canis familiaris; TNFα XM_027099307_Lagenorhynchus obliquidens.

Primers for qPCR (Macrogen, Seoul, South Korea) (Table 1) were designed within conserved regions using NCBI Primer-BLAST (Ye et al., 2012) and recommended parameters for designing SYBR® Green primers (Thornton & Basu, 2011). Secondary structures and specificity against non-specific sequences for each primer set were assessed in silico using BeaconDesigner™ (http://www.premierbiosoft.com/qOligo/Oligo.jsp?PID=1) and NCBI Primer-BLAST (Ye et al., 2012), respectively. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was selected as a reference gene for this study given its stability in a variety of sample types and its validation in many species including domestic animals, marsupials and marine mammals (Beineke et al., 2004; Fonfara et al., 2008; Maher et al., 2014; Puech et al., 2015; Sharp et al., 2006). Primers for GAPDH (Macrogen, Seoul, South Korea) were selected from a previous publication that used Genbank sequences for Canis familiaris (Peters et al., 2004) and its performance was optimised to the study conditions.

Blood collection, RNA extraction and reverse transcription

Blood samples (0.5 mL) from domestic dog (C. familiaris, n = 4), cattle (Bos Taurus, n = 3) and sheep (Ovis aries, n = 3) were collected from brachial, tail and jugular veins, respectively into EDTA tubes (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) and then centrifuged at 5,000×g for up to 3 min. Plasma was removed using a sterile disposable pipette, and the remaining red blood cells and buffy coat were resuspended in 1,300 µl RNAlater™ (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and then transferred into cryovials to approximate field storage conditions. Samples were initially stored at 4 °C for 2–4 days and then at −20 °C until RNA extraction was performed within 12 months of blood collection. RNA extractions from the same species were combined and used as pooled samples for further applications.

In 2010, four blood samples (0.5 mL) collected from the brachial vein from N. cinerea pups for a previous study (Marcus, Higgins & Gray, 2014) (Government of South Australia Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources; Wildlife Ethics Committee approvals 3–2008 and 3–2011 and Scientific Research Permits A25088/4–5) were immediately transferred into EDTA tubes (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) and processed as described above. Samples were initially stored at 4 °C for 2–4 days and then at −20 °C until RNA extraction was performed in 2018. RNA extractions were combined and used as pooled samples for further applications.

For RNA extractions, samples in RNAlater™ were thawed at room temperature, centrifuged at 16,000×g for 1 min, and the supernatant of RNAlater™ discarded from the cell pellet. Total RNA extraction was performed on the cell pellet using the RiboPure™-Blood Kit (Ambion, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, such that the equivalent of 200 µl of whole blood was used per extraction. The RNA concentration and purity were assessed (A260/A280) using a NanoDrop 1000, Thermo Scientific™ (Waltham, MA, USA) and RNA stored as multiple aliquots at −80 °C for subsequent use.

For analysis, aliquots of RNA were thawed on ice, and two sequential DNase treatments were performed using the RNase-free DNase I (provided in the RNA extraction kit) to eliminate genomic DNA (gDNA). Reverse transcription was performed on 50–100 ng of RNA template in a 20 µl reaction with the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher™, Carlsbad, CA, USA), with a combination (50:50) of random hexamer and oligo(dT)18 primers to improve the sensitivity of cDNA synthesis (Ferrante, Hunter & Wellehan, 2018; Gallup, 2011). cDNA was stored as multiple aliquots at −20 °C for subsequent use.

Real-time PCR optimisation and validation

Optimisation and validation parameters were achieved following recommendations for qPCR assays from Bustin et al. (2009) (MIQE guidelines). All qPCR assays were performed using SYBR Green (SsoAdvanced™ Universal SYBR® Green Supermix, BioRad) on a CFX96 Real-Time cycler (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA). Cycling conditions were optimised by annealing temperature (Ta) gradient and evaluation of three primer concentrations (100, 200 and 300 nM). Optimal parameters were determined based on those that yielded a single, sharp peak in the melt curve analysis with the lowest quantification cycle (Ct) for each primer pair (Table 1).

Amplifications were performed in white 8-strip PCR tubes (BioRad, California, USA), following manufacturer’s instructions for the SYBR Green Supermix in a 20 µl reaction with each primer pair at optimised concentration and 4 µl of cDNA template. In addition, “no-reverse transcription” controls (NRT), and “no template” controls (NTC) of RNase-DNase free water, were included in each run to check for gDNA contamination and the formation of primer-dimers, respectively. Under identical qPCR cycling conditions, reactions were validated across cDNA templates from N. cinerea, C. familiaris, B. taurus and O. aries. Amplification conditions were 95 °C for 1 min (1 cycle); 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 20 s (40 cycles). After each cycling protocol, a melt curve analysis was generated by heating from 65 °C to 95 °C with 0.5 °C increments for 5 s to confirm the absence of non-specific products or primer dimers and define melting temperatures (Tm) for each amplicon. The size of each qPCR product was confirmed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and identity of the amplicon was further confirmed by DNA sequence analysis (Macrogen, Seoul, South Korea) and comparison with nucleotide sequences of terrestrial and marine mammals using the NCBI BLAST programme (Altschul et al., 1990).

Confirmed qPCR products were removed from the plates and diluted for further use as a template in standard curves. Amplification efficiencies for each gene of interest (GOI) and the reference gene (GAPDH) were determined for each species through a standard curve using serial dilutions of qPCR product with a minimum of five standards with the dilution extending at least to that producing a Ct of 34. The efficiency (E) and linearity (R2) of each primer pair were calculated on these curves using the Bio-Rad CFX Maestro software 1.1 (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) with automatic threshold settings. Linear regression of the qPCR standard curves was recalculated with Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA; 2016). Primer pairs with efficiencies of 100% ± 10% and R2 value > 0.96 were considered optimised for qPCR (IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IFNγ and TNFα) following MIQE recommended ranges. The limit of quantification (LoQ) was based on the linear operating range of each assay (Berdal & Holst-Jensen, 2001). Assays that showed linear and efficient amplification but that produced Ct values above the dynamic range of qPCR (Ct alues >35) when applied to N. cinerea pup blood samples, were selected for subsequent development of novel ddPCR. As the assays were developed for use in relative expression studies using the delta Ct method, absolute quantification and limits of detection (LOD) were not derived using quantified standards. Quantified standards were, however used for direct comparison of sensitivity of ddPCR vs qPCR in IL-4 and IFNγ assays.

ddPCR assays for Neophoca cinerea

qPCR products obtained from the amplification of N. cinerea samples with the IL-4 and IFNγ qPCR primers formerly described in this study were sequenced and aligned using the CLC Main Workbench 6.9.1 (Qiagen, Redwood City, CA, USA). NCBI Primer-BLAST programme (Ye et al., 2012) was used to design N. cinerea primer-probe pairs for ddPCR following recommended parameters from the Droplet Digital™ PCR Applications Guide (www.bio-rad.com). The primers and probes sequences (Macrogen, Seoul, South Korea) are listed in Table 2. The in silico tool ‘PCR Primer Stats’ (http://www.bioinformatics.org/sms2/pcr_primer_stats.html) was used to evaluate primer-probe pairs melting temperature, GC content and secondary structures (Stothard, 2000). Probes were labelled with FAM (F) fluorophore and quenched with non-fluorescent black hole quenchers number 1 (BHQ-1).

Table 2. Characteristics of cytokine primers developed in the study for ddPCR for IL-4 and IFNγ in N. cinerea.

| Gene name | Primer sequences (5′->3′) | Probe fluorophore | Annealing/Extension (°C, s) | Optimal primer/probe concentration (nM) | Amplicon size (Bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-4 | F: TCACCTCCCAACTGATTCCAA | 60, 20 | 400 | 132 | |

| R: ACGAGTCGTTTCTCGCTGT | 60, 20 | 400 | |||

| P: GCACTCACCAGCACCTTTGTCCA | FAM | 60, 20 | 100 | ||

| IFNy | F: AGCTGATTCGAATTCCCGTGA | 58, 20 | 400 | 95 | |

| R: TCTGACTCCTTTTCCGCTTCC | 58, 20 | 400 | |||

| P: TGCAGGTCCAGCGCAAAGCGATA | FAM | 58, 20 | 100 |

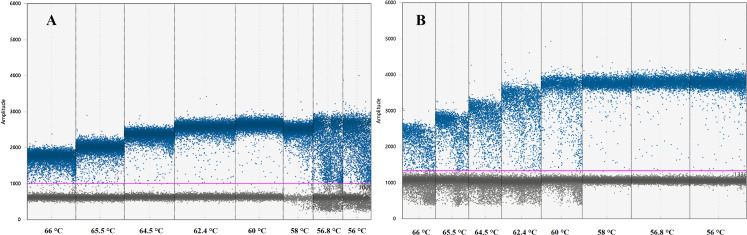

Instruments, reagents and consumables for the ddPCR workflow were supplied by Bio-Rad (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Optimal ddPCR annealing temperatures for IL-4 and IFNγ assays were defined by performing a temperature gradient in the annealing/extension step of the thermal cycling protocol as suggested by ddPCR guidelines (Huggett et al., 2013). All ddPCR optimisation assays were performed using the ddPCR™ Supermix for Probes (no dUTP) master mix in a C1000 Touch™ Thermal Cycler. The fluorescence difference between NTC and positive samples within a single run was used to set a threshold between negative and positive droplets. Positive droplets show increased fluorescent amplitude when compared to the negative droplets and contain at least one copy of the target per sample. The optimal annealing temperature for these assays was defined as the one giving the largest difference in fluorescence between negative and positive droplets (Table 2; Fig. 1) (Huggett et al., 2013).

Figure 1. Graph displaying fluorescence amplitude plotted against the annealing temperature gradient for digital droplet PCR.

Blue dots above the pink line (threshold) represents positive PCR amplification droplets for (A) IL-4 and (B) IFNγ. Grey dots represent negative droplets. Each column represents one of eight ddPCR reactions across an annealing temperature gradient. The optimal annealing temperature giving the largest difference in fluorescence between negative and positive droplets was 60 °C for (A) IL-4 and 58 °C for (B) IFNγ. Both assays can work simultaneously at 59 °C.

ddPCR master mix reactions included 10 µl of the Supermix, one µl of each primer and probe, six µl of cDNA from pooled N. cinerea samples and RNase-DNase free water to complete a 20 µl total volume reaction (Table 2). PCR mix and Droplet Generation oil for Probes were added to corresponding wells in the Droplet Generator DG8™ Cartridge and covered with DG8™ Gaskets following the manufacturer’s instructions. Droplets were generated by using the QX100™ Droplet Generator, gently transferred to a clean 96-well PCR plate and sealed using a PCR Plate Sealer. Amplification was performed using the following cycling conditions: an initial enzyme activation period of 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles consisting of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s and annealing/extension step of 59 °C for 1 min, and followed by an enzyme deactivation period of 10 min at 95 °C and a 4 °C indefinite hold. The overall ramp rate was set at 2 °C s−1. Droplets were read as positive or negative with a QX200 Droplet Reader, and further analysis was performed using the Quanta-Soft Analysis Pro™ software (Bio-Rad). The software, based on fluorescence amplitude, establishes a threshold between positive and negative droplets. Positive droplets are converted to copy numbers in the PCR mix based on Poisson algorithms (Droplet Digital™ PCR Applications Guide).

To assess linearity (R2), efficiency (E) and to compare the limits of detection (LoD) and quantification (LoQ) of qPCR and ddPCR, IL-4 and IFNγ consensus sequences were selected to synthesise double-stranded DNA standards (gBlocks® gene fragments; Integrated DNA Technologies, Singapore). Each DNA standard was resuspended in Tris EDTA buffer (The Bosch Institute, Faculty of Medicine, The University of Sydney) to reach a final concentration of 10 ng µl−1 according to the manufacturer’s instructions with subsequent storage at −20 °C. For qPCR, a calibration curve (regression line) was performed with 10-fold serial dilutions of the standard ranging from 106 to one target copies µl−1 and six technical replicates for each dilution. For ddPCR, 5-fold serial dilutions ranged from 200 to 0 target copies µl−1 with three replicates for each dilution. LoD and LoQ were calculated with Microsoft Excel (2016) as 3.3 and 10 times, respectively, the standard deviation of the y-intercept of the regression line, divided by the slope of the corresponding calibration curve (FDA, 1996; Mohamad, 2018).

Results

Real-time qPCR design and validation

The primer pairs designed in this study measured cytokine gene expression in mammalian species in separate evolutionary clades, representing terrestrial (domestic dog, sheep and cattle) and the Australian sea lion. mRNA sequences from qPCR products showed high homology to available mammalian sequence data, with values ranging from 86 to 100% (Table 3).

Table 3. Nucleotide identity of qPCR products for IL-4, IL-6, IFNγ, IL-10 and TNFα represented by the best match in BLASTn search (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/) in the four target species.

| Target gene | qPCR product | % Best match | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-4 | Neophoca cinerea | 98 | Eumetopias jubatus XM_028103636.1 |

| Canis familiaris | 95 | Canis familiaris EF095771.1 | |

| IL-6 | Neophoca cinerea | 100 | Zalophus californianus XM_027574842.1 |

| Canis familiaris | 88 | Canis familiaris AF349534.1 | |

| IFNγ | Neophoca cinerea | 98 | Enhydra lutris XM_022495107.1 |

| Canis familiaris | 97 | Canis lupus XM_025476664.1 | |

| IL-10 | Neophoca cinerea | 100 | Eumetopias jubatus XM_028120121.1 |

| Canis familiaris | 95 | Canis familiaris EU426968.1 | |

| Bos taurus | 95 | Bos indicus KX013148.1 | |

| Ovis aries | 97 | Equus caballus XM_023640225.1 | |

| TNFα | Neophoca cinerea | 90 | Eumetopias jubatus XM_028120686.1 |

| Canis familiaris | 87 | Vulpes vulpes KM892854.1 | |

| Bos taurus | 95 | Bos taurus NM_173966.3 | |

| Ovis aries | 86 | Ovis aries EF446377.1 |

The integrity of isolated RNA was demonstrated in all blood samples from every species by the amplification of GAPDH mRNA (Ct 25 ± 3.1, mean ± SD). Optimal qPCR parameters allowed amplification of IL-4 (Australian sea lion and dog), IL-6 (Australian sea lion and dog), IL-10 (all four targeted species), TNFα (all four targeted species), IFNγ (Australian sea lion and dog) and GAPDH (all four targeted species), using the same cycling protocol, with a combined annealing and extension step at 60 °C. The defined optimal parameters for the assays are shown in Table 1. In addition, the presence of a single specific product was confirmed by melt curve analysis (Figs. S1–S4), agarose gel electrophoresis and sequencing. The absence of non-specific products and primer-dimers was confirmed (Figs. S1–S4). No amplification was detected in NRT controls and NTC. Two consecutive DNAse treatments were required to eliminate evidence of gDNA in NRT controls. All assay efficiencies ranged between 87% (Ovis aries TNFα) and 111% (Bos taurus IL-10) and had strong linearity (R2) (Table 4). Although sample sizes were too small for comparison, the low expression of IL-4 and IFNγ in N. cinerea was consistent with levels in canine samples that we assessed (Ct 32 ± 2.5, n = 4).

Table 4. qPCR: efficiency (E%) and linearity (R2) for IL-4, IL-6, IFNγ, IL-10, TNFα and GAPDH in their respective targeted species.

| Target gene | Species | Slope | R2 | E (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-4 | Neophoca cinerea | −3.267 | 0.987 | 102 |

| Canis familiaris | −3.244 | 0.990 | 103 | |

| IL-6 | Neophoca cinerea | −3.293 | 0.985 | 101 |

| Canis familiaris | −3.351 | 0.999 | 99 | |

| IFNγ | Neophoca cinerea | −3.229 | 0.999 | 104 |

| Canis familiaris | −3.225 | 0.996 | 103 | |

| IL-10 | Neophoca cinerea | −3.132 | 0.996 | 95 |

| Canis familiaris | −3.319 | 0.998 | 100 | |

| Bos taurus | −3.083 | 0.994 | 111 | |

| Ovis aries | −3.167 | 0.996 | 107 | |

| TNFα | Neophoca cinerea | −3.374 | 0.989 | 98 |

| Canis familiaris | −3.271 | 0.936 | 102 | |

| Bos taurus | −3.624 | 0.998 | 89 | |

| Ovis aries | −3.684 | 0.999 | 87 | |

| GAPDH | Neophoca cinerea | −3.385 | 0.992 | 106 |

| Canis familiaris | −3.581 | 0.998 | 87 | |

| Bos taurus | −3.288 | 0.979 | 101 | |

| Ovis aries | −3.371 | 0.998 | 98 |

ddPCR assays for Neophoca cinerea

The ddPCR primers and probe assays designed in this study effectively amplified N. cinerea blood mRNA. The forward-reverse and probe sequences of each assay are listed in Table 2. Gene sequence data obtained for both primer-probe pairs was BLASTn compared against similar mammalian species genes, and the results show 98% homology with marine mammals (Table 5). No amplification was detected in NTC.

Table 5. BLASTn results of identity for Neophoca cinerea qPCR amplified genes represented by the best match with pinnipeds’ sequences in BLASTn search (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/).

| Target gene | % Best match | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|

| IL-4 | 98 | Eumetopias jubatus XM_028103636.1 |

| IFNγ | 98 | Phoca vitulina XM_032420714.1 |

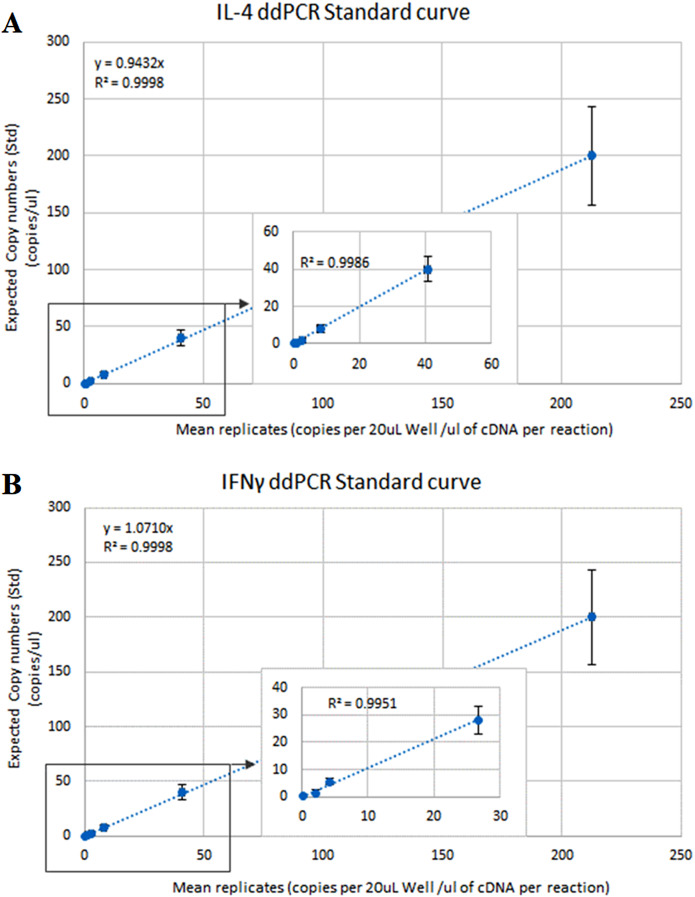

The optimal ddPCR annealing/extension temperature for IL-4 and IFNγ defined by a temperature gradient was 60°C and 58°C, respectively (Fig. 1). The defined optimal parameters for the assays are shown in Table 2. LoD and LoQ were confirmed to be lower in ddPCR than in qPCR (Table 6; Fig. 2). Quantification of IFNγ and IL-4 in the pooled N. cinerea samples indicated 69 and 13 copies per reaction, respectively (Table 6).

Table 6. qPCR and ddPCR validation parameters for IL-4 and IFNγ primer-probe pairs in Neophoca cinerea.

| qPCR | ddPCR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target gene | E (%) | R2 | LoD | LoQ | Copies in pooled samples | LoD | LoQ |

| (Copy numbers) | (Copy numbers) | ||||||

| IL-4 | 101 | 0.996 | 6 | 199 | 13 | 4.19 | 12.68 |

| IFNγ | 101 | 0.997 | 5 | 119 | 69 | 3.48 | 10.54 |

Note:

qPCR efficiency (E%), linearity (R2), Limit of Detection (LoD) and Limit of Quantification (LoQ). ddPCR Quanta-Soft Analysis ProTM™ software copy number per reaction for Neophoca cinerea pooled samples and LoD and LoQ of the assays.

Figure 2. ddPCR calibration curves (regression lines) for the calculation of the Limit of Detection (LoD) and Limit of Quantification (LoQ) for IL-4 and IFNγ assays in Neophoca cinerea.

The x-axis represents the average (triplicates) copies of (A) IL-4 and (B) IFNγ per 20 μL reaction to the quantity of cDNA used in the PCR reaction (Quanta-Soft Analysis ProTM™ software). The y-axis represents 5-fold series dilutions of DNA standards. Inset graphs show linearity of the assays in the more diluted standards.

Discussion

Cytokine mRNA qPCR has become a broadly used and affordable tool to establish cytokine expression profiles in animals but has been limited by the lack of species-specific reagents (Ferrante, Hunter & Wellehan, 2018; Funke et al., 2002; Maher et al., 2014; Maissen-Villiger et al., 2016; Puech et al., 2015). In this study, optimisation and validation of SYBR green RT-qPCR assays, cross-reactive to diverse mammalian species, was performed to allow relative quantification of mRNA of five important cytokines (i.e. IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IFNγ and TNFα). Primer sets for IL-4, IL-6 and IFNγ cross-reacted in dog and Australian sea lion samples, whereas those for IL-10 and TNFα also amplified across sheep and cattle. The broad cross-reactivity suggests that these primer sets are likely to cross react across several other mammalian species.

Studies of basal cytokine levels in marine mammals are forthcoming but still limited (Beineke et al., 2007; Beineke et al., 2004; Ferrante, Hunter & Wellehan, 2018; Hofstetter et al., 2017) and, consistent with our study, others have encountered challenges with sensitivity. Sitt et al. (2016) determined that IL-4 transcripts were typically absent in killer whales (Orcinus orca) and levels of IL-4 in domestic pig (Sus scrofa) remained low even after lymphocyte stimulation (Murtaugh et al., 1996). In the present study, qPCR of mRNA from whole blood was quantifiable for IL-6, IL-10, TNFα and GAPDH but despite optimal specificity and efficiency, IL-4 and IFNγ Ct values for samples from N. cinerea pups were outside the limits of quantification (>35). Separation and stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PMBCs) is often performed for the quantification of cytokine gene expression (Beineke et al., 2004; King et al., 1993; Levin et al., 2014) and yields much greater concentrations of target mRNA; but these methods are often not feasible under field conditions and may not represent natural expression as closely as cytokine levels in non-stimulated whole blood samples. The novel ddPCR assays overcame this limitation for samples collected from Australian sea lion pups. This method represents a very sensitive technique capable of assessing low abundant targets, confirmed by the lower LoD and LoQ than qPCR. Thus, the technique shows a lot of promise for cytokine gene expression studies involving low abundant targets or samples with carryover of inhibitors from RNA extraction or cDNA synthesis methods, as can occur when field samples associated with wildlife studies cannot be collected and stored under ideal conditions (Rački et al., 2014; Taylor, Laperriere & Germain, 2017).

It was not possible to ensure that the primer pairs developed in this study did not span exon-exon junctions. It is therefore recommended that a thorough removal of gDNA is performed when following the methods presented here. Similar to a previous study Schwochow et al. (2012), two DNase treatments were needed to ensure the removal of contaminating gDNA.

The set of primers developed in this study have potential applications to immunological studies across multiple species, including wildlife, expanding the toolkit for researchers in the future to identify immunological markers of innate, T-helper-1 and T-helper-2 pathways in mammals. To our knowledge, the ddPCR assay developed for Australian sea lions is the first one to be reported in a pinniped species and is presented as an alternative for samples that contain a low concentration of target or those that could be affected by inhibitors. However, further investigation is necessary to explore the full potential of this approach.

Conclusion

In summary, SYBR Green RT-qPCR assays were developed to quantify cytokine gene expression across diverse mammalian species. The diversity of species strongly suggests that the assays have potential for application beyond the Australian sea lion to many other threatened wildlife species. The sensitivity of methods described here indicates that most are of use in mRNA extracts from whole blood, increasing their utility for analysis of field samples, where immediate sample processing is limited. Conveniently, they can also be applied under the same optimised cycling conditions in their respective targeted species.

The novel ddPCR methods described here enabled detection of low expressed genes, like IL-4 and IFNγ in N. cinerea pups, providing comparative advantages when working with unstimulated tissues and limiting sample volumes as in the case of fieldwork-based wildlife studies.

Supplemental Information

Melting curves of dilutions from standard curves for each target. In the x-axis, single visible peaks represent the melting temperature (Tm) of the double-stranded DNA complexes. The y-axis represents the Relative Fluorescence unit (RFU) (-d(RFU)/dT).

Melting curves of dilutions from standard curves for each target. In the x-axis, single visible peaks represent the melting temperature (Tm) of the double-stranded DNA complexes. The y-axis represents the Relative Fluorescence unit (RFU) (-d(RFU)/dT).

Melting curves of dilutions from standard curves for each target. In the x-axis, single visible peaks represent the melting temperature (Tm) of the double-stranded DNA complexes. The y-axis represents the Relative Fluorescence unit (RFU) (-d(RFU)/dT).

Melting curves of dilutions from standard curves for each target. In the x-axis, single visible peaks represent the melting temperature (Tm) of the double-stranded DNA complexes. The y-axis represents the Relative Fluorescence unit (RFU) (-d(RFU)/dT).

Excel spreadsheets with the standard curves and calculations for Limit of detection and limit of quantification for IL-4 and IFNy primer sets described in the manuscript.

Excel spreadsheets with the standard curves and calculations for Limit of detection and limit of quantification for IL-4 and IFNy primer sets described in the manuscript.

qPCR Neophoca cinerea sequence analysis results (Macrogen, Seoul, South Korea).

Acknowledgments

Canine, bovine and ovine blood samples were surplus from diagnostic specimens provided by Christine Black and Kathy Brammall from the Veterinary Pathology Diagnostic Services (VPDS) operating within the Sydney School of Veterinary Science at the University of Sydney. Assistance with sample collection from Australian sea lion pups was provided by Alan Marcus. Staff at Seal Bay Conservation Park, Department for Environment and Water (DEW), South Australia, provided logistical support and field assistance. The authors would like to thank Dr. Donna Lay and Dr. Sheng Hua from the Bosch Institute from the Faculty of Medicine and Health at the University of Sydney, for valuable insights and feedback during the implementation of ddPCR in this study and Alan Marcus for comments on early drafts.

Funding Statement

This research was financially supported by CONICYT PFCHA through the postgraduate scholarship “MAGISTER BECAS CHILE 2017” provided to María-Ignacia Meza Cerda (73181623). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

María-Ignacia Meza Cerda conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analysed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Rachael Gray conceived and designed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Damien P Higgins conceived and designed the experiments, analysed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Animal Ethics

The following information was supplied relating to ethical approvals (i.e., approving body and any reference numbers):

The Government of South Australia, Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Wildlife Ethics Committee approvals provided full approval for this research (3–2008, 3–2011).

Field Study Permissions

The following information was supplied relating to field study approvals (i.e., approving body and any reference numbers):

Fieldwork was approved by the Government of South Australia Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources [Scientific Research Permits (A25088/4–5)].

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

Raw data are available in the Supplemental Files.

References

- Abo-Aziza et al. (2020).Abo-Aziza FAM, Hendawy SHM, Oda SS, Aboelsoued D, El Shanawany EE. Cell-mediated and humoral immune profile to hydatidosis among naturally infected farm animals. Veterinary World. 2020;13(1):214–221. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2020.214-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul et al. (1990).Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1990;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker et al. (2018).Baker CS, Steel D, Nieukirk S, Klinck H. Environmental DNA (eDNA) from the wake of the whales: droplet digital PCR for detection and species identification. Frontiers in Marine Science. 2018;5:275. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beineke et al. (2007).Beineke A, Siebert U, Muller G, Baumgartner W. Increased blood interleukin-10 mRNA levels in diseased free-ranging harbor porpoises (Phocoena phocoena) Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 2007;115(1–2):100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beineke et al. (2004).Beineke A, Siebert U, van Elk N, Baumgärtner W. Development of a lymphocyte-transformation-assay for peripheral blood lymphocytes of the harbor porpoise and detection of cytokines using the reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 2004;98(1–2):59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdal & Holst-Jensen (2001).Berdal K, Holst-Jensen A. Roundup ready® soybean event-specific real-time quantitative PCR assay and estimation of the practical detection and quantification limits in GMO analyses. European Food Research and Technology. 2001;213(6):432–438. doi: 10.1007/s002170100403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boeuf et al. (2005).Boeuf P, Vigan-Womas I, Jublot D, Loizon S, Barale J-C, Akanmori BD, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Behr C. CyProQuant-PCR: a real time RT-PCR technique for profiling human cytokines, based on external RNA standards, readily automatable for clinical use. BMC immunology. 2005;6(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen et al. (2006).Bowen L, Aldridge B, Beckmen K, Gelatt T, Rea L, Burek K, Pitcher K, Stott JL. Differential expression of immune response genes in Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus): an indicator of ecosystem health? EcoHealth. 2006;3(2):109–113. doi: 10.1007/s10393-006-0021-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen et al. (2012).Bowen L, Miles AK, Murray M, Haulena M, Tuttle J, Van Bonn W, Adams L, Bodkin JL, Ballachey B, Estes J, Tinker MT, Keister R, Stott JL. Gene transcription in sea otters (Enhydra lutris); development of a diagnostic tool for sea otter and ecosystem health. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2012;12(1):67–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.03060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock, Murdock & Martin (2014).Brock PM, Murdock C, Martin L. The history of ecoimmunology and its integration with disease ecology. Integrative and Comparative Biology. 2014;54(3):1–10. doi: 10.1093/icb/icu046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin et al. (2009).Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, Wittwer CT. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clinical Chemistry. 2009;55(4):611–622. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin et al. (2005).Bustin SA, Benes V, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR—a perspective. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 2005;34(3):597–601. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen et al. (2016).Chen IH, Wang JH, Chou SJ, Wu YH, Li TH, Leu MY, Chang WB, Yang WC. Selection of reference genes for RT-qPCR studies in blood of beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) PeerJ. 2016;4:e1810. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das et al. (2008).Das K, Siebert U, Gillet A, Dupont A, Di-Poï C, Fonfara S, Mazzucchelli G, De Pauw E, De Pauw-Gillet M-C. Mercury immune toxicity in harbour seals: links to in vitro toxicity. Environmental Health. 2008;7(1):52. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-7-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Prete et al. (1993).Del Prete G, De Carli M, Almerigogna F, Giudizi MG, Biagiotti R, Romagnani S. Human IL-10 is produced by both type 1 helper (Th1) and type 2 helper (Th2) T cell clones and inhibits their antigen-specific proliferation and cytokine production. Journal of Immunology. 1993;150:353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fair et al. (2017).Fair PA, Schaefer AM, Houser DS, Bossart GD, Romano TA, Champagne CD, Stott JL, Rice CD, White N, Reif JS. The environment as a driver of immune and endocrine responses in dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) PLOS ONE. 2017;12(5):e0176202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA (1996).FDA . International conference on harmonisation; guideline on the validation of analytical procedures: methodology. Silver Spring: Food and Drug Administration Agency; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante, Hunter & Wellehan (2018).Ferrante JA, Hunter ME, Wellehan JFX. Development and validation of quantitative PCR assays to measure cytokine transcript levels in the florida manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris) Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 2018;54(2):283–294. doi: 10.7589/2017-06-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonfara et al. (2008).Fonfara S, Kakuschke A, Rosenberger T, Siebert U, Prange A. Cytokine and acute phase protein expression in blood samples of harbour seal pups. Marine Biology. 2008;155(3):337–345. doi: 10.1007/s00227-008-1031-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fonfara, Siebert & Prange (2007).Fonfara S, Siebert U, Prange A. Cytokines and acute phase proteins as markers for infection in Harbor Porpoises (Phocoena phocoena) Marine Mammal Science. 2007;23(4):931–942. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2007.00140.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Funke et al. (2002).Funke C, Aldridge A, Leutenegger C, Smith BR, Stott J, Gulland F, Van Bonn W. Development of a real-time quantitative RT-PCR (Taqman®) assay to measure cytokine profiles in California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) and Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) Albufeira: International Association for Aquatic Animal Medicine; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup (2011).Gallup J. qPCR inhibition and amplification of difficult templates. In: Kennedy S, Oswald N, editors. PCR Troubleshooting and Optimization: The Essential Guide. Norfolk: Caister Academic; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsworthy (2015).Goldsworthy S. Neophoca cinerea. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015;2015:e.T14549A45228341. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsworthy et al. (2009).Goldsworthy S, McKenzie J, Shaughnessy P, McIntosh R, Page B, Campbell R. Update of the report: understanding the impediments to the growth of Australian sea lion populations—SARDI research—report series no. 356. Adelaide: Department of the Environment Water Heritage and The Arts, South Australian Research and Development Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hindson et al. (2013).Hindson CM, Chevillet JR, Briggs HA, Gallichotte EN, Ruf IK, Hindson BJ, Vessella RL, Tewari M. Absolute quantification by droplet digital PCR versus analog real-time PCR. Nature Methods. 2013;10(10):1003–1005. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstetter et al. (2017).Hofstetter AR, Eberle KC, Venn-Watson SK, Jensen ED, Porter TJ, Waters TE, Sacco RE. Monitoring bottlenose dolphin leukocyte cytokine mRNA responsiveness by qPCR. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(12):e0189437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggett et al. (2013).Huggett JF, Foy CA, Benes V, Emslie K, Garson JA, Haynes R, Hellemans J, Kubista M, Mueller RD, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, Wittwer CT, Bustin SA. The digital MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative digital PCR experiments. Clinical Chemistry. 2013;59(6):892–902. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.206375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue et al. (1999).Inoue Y, Itou T, Sakai T, Oike T. Cloning and sequencing of a bottle-nosed dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) interleukin-4-encoding cDNA. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science. 1999;61(6):693–696. doi: 10.1292/jvms.61.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King et al. (1993).King DP, Robinson I, Hay AWM, Evans SW. Identification and partial characterization of common seal (Phoca vitulina) and grey seal (Haliochoerus grypus) interleukin-6-like activities. Developmental & Comparative Immunology. 1993;17(5):449–458. doi: 10.1016/0145-305X(93)90036-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King et al. (1996).King DP, Schrenzel MD, McKnight ML, Reidarson TH, Hanni KD, Stott JL, Ferrick DA. Molecular cloning and sequencing of interleukin 6 cDNA fragments from the harbor seal (Phoca vitulina), killer whale (Orcinus orca), and Southern sea otter (Enhydra lutris nereis) Immunogenetics. 1996;43(4):190–195. doi: 10.1007/BF00587299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau et al. (2015).Lau Q, Chow N, Gray R, Gongora J, Higgins DP. Diversity of MHC DQB and DRB genes in the endangered Australian sea lion (Neophoca cinerea) Journal of Heredity. 2015;106(4):395–402. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esv022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehnert et al. (2019).Lehnert K, Siebert U, Reissmann K, Bruhn R, McLachlan MS, Muller G, Van Elk CE, Ciurkiewicz M, Baumgartner W, Beineke A. Cytokine expression and lymphocyte proliferative capacity in diseased harbor porpoises (Phocoena phocoena)—biomarkers for health assessment in wildlife cetaceans. Environmental Pollution. 2019;247:783–791. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin (2018).Levin M. Marine mammal immunology. In: Gulland F, Dierauf L, Whitman K, editors. CRC Handbook of Marine Mammal Medicine. Third Edition. Boca Raton: CRC Press (Taylor & Francis); 2018. p. 1124. [Google Scholar]

- Levin et al. (2014).Levin M, Romano T, Matassa K, De Guise S. Validation of a commercial canine assay kit to measure pinniped cytokines. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 2014;160(1–2):90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher et al. (2014).Maher IE, Griffith JE, Lau Q, Reeves T, Higgins DP. Expression profiles of the immune genes CD4, CD8β, IFNγ, IL-4, IL-6 and IL-10 in mitogen-stimulated koala lymphocytes (Phascolarctos cinereus) by qRT-PCR. PeerJ. 2014;2:e280. doi: 10.7717/peerj.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maissen-Villiger et al. (2016).Maissen-Villiger CA, Schweighauser A, van Dorland HA, Morel C, Bruckmaier RM, Zurbriggen A, Francey T. Expression profile of cytokines and enzymes mRNA in blood leukocytes of dogs with leptospirosis and its associated pulmonary hemorrhage syndrome. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(1):e0148029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, Higgins & Gray (2014).Marcus A, Higgins DP, Gray R. Epidemiology of hookworm (Uncinaria sanguinis) infection in free-ranging Australian sea lion (Neophoca cinerea) pups. Parasitology Research. 2014;113(9):3341–3353. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3997-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamad (2018).Mohamad T. Limit of Blank (LOB), Limit of Detection (LOD), and Limit of Quantification (LOQ) Organic & Medicinal Chemistry IJ. 2018;7(5):555722. doi: 10.19080/OMCIJ.2018.07.555722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murtaugh et al. (1996).Murtaugh MP, Baarsch MJ, Zhou Y, Scamurra RW, Lin G. Inflammatory cytokines in animal health and disease. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 1996;54(1–4):45–55. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2427(96)05698-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbergh et al. (1999).Overbergh L, Valckx D, Waer M, Mathieu C. Quantification of murine cytokine mRNAs using real time quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR. Cytokine. 1999;11(4):305–312. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1998.0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters et al. (2004).Peters IR, Helps CR, Hall EJ, Day MJ. Real-time RT-PCR: considerations for efficient and sensitive assay design. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2004;286(1–2):203–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puech et al. (2015).Puech C, Dedieu L, Chantal I, Rodrigues V. Design and evaluation of a unique SYBR Green real-time RT-PCR assay for quantification of five major cytokines in cattle, sheep and goats. BMC Veterinary Research. 2015;11(1):65. doi: 10.1186/s12917-015-0382-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rački et al. (2014).Rački N, Dreo T, Gutierrez-Aguirre I, Blejec A, Ravnikar M. Reverse transcriptase droplet digital PCR shows high resilience to PCR inhibitors from plant, soil and water samples. Plant Methods. 2014;10(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s13007-014-0042-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostami-Rad, Jafari & Yousofi Darani (2018).Rostami-Rad S, Jafari R, Yousofi Darani H. Th1/Th2-type cytokine profile in C57 black mice inoculated with live Echinococcus granulosus protoscolices. Journal of Infection and Public Health. 2018;11(6):834–839. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwochow et al. (2012).Schwochow D, Serieys LE, Wayne RK, Thalmann1 Olaf. Efficient recovery of whole blood RNA—a comparison of commercial RNA extraction protocols for high-throughput applications in wildlife species. BMC Biotechnology. 2012;12(1):1915. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-12-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp et al. (2006).Sharp JA, Cane KN, Mailer SL, Oosthuizen WH, Arnould JPY, Nicholas KR. Species-specific cell–matrix interactions are essential for differentiation of alveoli like structures and milk gene expression in primary mammary cells of the Cape fur seal (Arctocephalus pusillus pusillus) Matrix Biology. 2006;25(7):430–442. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaughnessy et al. (2011).Shaughnessy P, Goldsworthy S, Hamer DJ, Page B, McIntosh R. Australian sea lions Neophoca cinerea at colonies in South Australia: distribution and abundance, 2004 to 2008. Endangered Species Research. 2011;13(2):87–98. doi: 10.3354/esr00317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shoda, Brown & Rice-Ficht (1998).Shoda LK, Brown WC, Rice-Ficht AC. Sequence and characterization of phocine interleukin 2. Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 1998;34(1):81–90. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-34.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitt et al. (2016).Sitt T, Bowen L, Lee CS, Blanchard MT, McBain J, Dold C, Stott JL. Longitudinal evaluation of leukocyte transcripts in killer whales (Orcinus orca) Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 2016;175:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitz et al. (2015).Spitz J, Becquet V, Rosen DSA, Trites AW. A nutrigenomic approach to detect nutritional stress from gene expression in blood samples drawn from Steller sea lions. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 2015;187:214–223. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Laurent, Béliveau & Archambault (1999).St-Laurent G, Béliveau C, Archambault D. Molecular cloning and phylogenetic analysis of beluga whale (Delphinapterus leucas) and grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) interleukin 2. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 1999;67(4):385–394. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2427(99)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stothard (2000).Stothard P. The sequence manipulation suite: javascript programs for analyzing and formatting protein and DNA sequences. BioTechniques. 2000;28(6):1102–1104. doi: 10.2144/00286ir01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Laperriere & Germain (2017).Taylor S, Laperriere G, Germain H. Droplet digital PCR versus qPCR for gene expression analysis with low abundant targets: from variable nonsense to publication quality data. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1):2409. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02217-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton & Basu (2011).Thornton B, Basu C. Real-time PCR (qPCR) primer design using free online software. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education. 2011;39(2):145–154. doi: 10.1002/bmb.20461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye et al. (2012).Ye J, Coulouris G, Zaretskaya I, Cutcutache I, Rozen S, Madden TL. Primer-BLAST: a tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13(1):134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman et al. (2014).Zimmerman LM, Bowden RM, Vogel LA, Tschirren B. A vertebrate cytokine primer for eco-immunologists. Functional Ecology. 2014;28(5):1061–1073. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Melting curves of dilutions from standard curves for each target. In the x-axis, single visible peaks represent the melting temperature (Tm) of the double-stranded DNA complexes. The y-axis represents the Relative Fluorescence unit (RFU) (-d(RFU)/dT).

Melting curves of dilutions from standard curves for each target. In the x-axis, single visible peaks represent the melting temperature (Tm) of the double-stranded DNA complexes. The y-axis represents the Relative Fluorescence unit (RFU) (-d(RFU)/dT).

Melting curves of dilutions from standard curves for each target. In the x-axis, single visible peaks represent the melting temperature (Tm) of the double-stranded DNA complexes. The y-axis represents the Relative Fluorescence unit (RFU) (-d(RFU)/dT).

Melting curves of dilutions from standard curves for each target. In the x-axis, single visible peaks represent the melting temperature (Tm) of the double-stranded DNA complexes. The y-axis represents the Relative Fluorescence unit (RFU) (-d(RFU)/dT).

Excel spreadsheets with the standard curves and calculations for Limit of detection and limit of quantification for IL-4 and IFNy primer sets described in the manuscript.

Excel spreadsheets with the standard curves and calculations for Limit of detection and limit of quantification for IL-4 and IFNy primer sets described in the manuscript.

qPCR Neophoca cinerea sequence analysis results (Macrogen, Seoul, South Korea).

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

Raw data are available in the Supplemental Files.