Abstract

Introduction

To investigate factors affecting glycemic control, oral antidiabetic drug (OAD) treatment distribution and self-care activities among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) who newly initiate OAD monotherapy in a real-world setting in Japan.

Research design and methods

A Real-world Observational Study on Patient Outcomes in Diabetes (RESPOND) is an ongoing, prospective, observational cohort study with follow-up at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months. Primary objectives include OAD treatment patterns (cross-sectional and longitudinal) among diabetes specialists versus non-specialists; adherence to diabetes self-care activities; quality of life; treatment satisfaction among patients and target attainment rates of parameters, including glycated hemoglobin. Here, we present the study design and baseline data.

Results

Of 1506 patients enrolled (June 2016–May 2017; 174 sites in Japan), 1485 were included in the baseline analysis (617 treated by specialists, 868 by non-specialists). Most patients were prescribed dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4Is) (specialist vs non-specialist, 54.1% vs 57.1%), then sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (13.9% vs 22.2%), metformin (20.3% vs 12.9%) and other OADs (<5% individually in both groups). Regardless of age, body mass index and glycated hemoglobin, DPP-4Is were the most commonly prescribed OADs by both specialists and non-specialists. About one-fifth and one-third of patients visiting specialists and non-specialists, respectively, received no advice on diet and exercise. The proportion of patients following self-care recommendations for diet and exercise (2/5 items on the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities) was significantly higher among those visiting specialists than non-specialists.

Conclusion

The use of newer OAD was common across a broad range of clinical characteristics in patients with T2DM who newly initiated monotherapy in Japan. However, patient-related and physician-related factors could affect the treatment changes during the following course of treatment. In addition, treatment outcome could vary with the observed difference in the level of patient education provided by diabetes specialists versus non-specialists.

Keywords: hypoglycemic agents, education

Significance of this study.

What is already known about this subject?

Treatment patterns regarding initial choice of oral antidiabetic drugs differ between countries, for example, in patients newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus, metformin is the most common initial therapeutic choice in Europe and the USA, compared with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in Japan.

What are the new findings?

Regardless of age, body mass index and glycated hemoglobin, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors were the oral antidiabetic drugs most commonly prescribed by both diabetes specialists and non-specialists in Japan.

A significantly higher proportion of patients aged ≥66 years (79.2% vs 65.5%, p<0.01) were prescribed dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors by specialists versus non-specialists.

About one-fifth and one-third of patients visiting specialists and non-specialists, respectively, did not receive any advice about diet and exercise.

The proportion of patients who followed the self-care recommendations for diet and exercise was significantly higher among those visiting specialists versus non-specialists except for low-level exercise, which was significantly higher among those visiting the non-specialist.

Significance of this study.

How might these results change the focus of research or clinical practice?

The results should encourage both specialists and non-specialists to understand patient characteristics better and improve patient education on diabetes self-care activities.

Introduction

In Japan, the 2019 estimate for diabetes prevalence among those aged 20–79 years was 7.4 million (7.9%), diabetes-related deaths was 71 513 per year, proportion of individuals with undiagnosed diabetes was 46.6% and economic burden associated with diabetes was US$3178.9 per person with diabetes.1 Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) generally have less obesity than patients in Western countries,2 which suggests a different etiology, especially in terms of the degree of insulin deficiency and insulin resistance. Therefore, real-world trends in oral antidiabetic drug (OAD) choice in Japan could be different from those in Western countries. As such, there is a need to study this patient population and evaluate the current trends in diabetes care and treatment in Japan.

The Japan Diabetes Society (JDS) guidelines recommend that patients newly diagnosed with T2DM should be initiated on diet and exercise therapy and lifestyle improvement if appropriate, in contrast to the guidelines in the USA and Europe, where metformin use is also recommended in the initial treatment.3–5 The JDS guidelines also recommend that pharmacological treatment should preferably be started as OAD monotherapy when glycemic control is inadequate after 2–3 months of lifestyle intervention. If target glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels determined in consideration of patient characteristics (generally <6.0%‒<8.0%) are not achieved with monotherapy after 2–3 months, treatment should be gradually intensified by adding or switching to another OAD with a different mode of action or an injectable such as a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist or insulin. Crucially, the JDS guidelines emphasize that the choice of drugs should be individualized for each patient according to their age, disease state and after consideration of the drug’s pharmacological and safety profile, as similarly recommended in the US and European guidelines.

Likewise, the OAD treatment options currently available in Japan are similar to those in the USA and Europe5 6 and include biguanides,7 dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4Is),8 sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2Is),9 α-glucosidase inhibitors, thiazolidinedione, sulfonylureas and glinides.7 However, as an initial OAD monotherapy, metformin is the most common choice in Europe10 and the USA according to guidelines recommending the first-line use of metformin,11 12 whereas DPP-4Is are the most common initial OAD choice in Japan where no designated first-line drug is proposed in the guidelines.2 13 It is important to highlight that the Japanese healthcare system provides universal coverage through national health insurance or employees’ health insurance, and patients with T2DM can freely select their own healthcare providers (diabetes specialists (specialists) or non-specialists) within the healthcare system.7 14

Different prescribing patterns between specialists and non-specialists may subsequently affect attainment of individualized treatment targets, quality of life (QoL) and self-care behavior. It is well known that self-care activities, such as following a diet plan, avoiding high-fat foods, increasing exercise, self-glucose monitoring and foot care are essential for patients with T2DM to effectively manage the disease.15 However, information regarding patient-related and physician-related factors that may influence the choice of agent from the OAD classes as initial monotherapy for the treatment of T2DM in Japan, treatment changes and outcomes is limited. Additionally, data on patient education provided by physicians regarding self-care activities and patients’ adherence to these self-care activities are needed.

To address these data gaps, this Real-world Observational Study on Patient Outcomes in Diabetes (RESPOND) aims to provide information on patient and physician characteristics while initiating OAD monotherapy; patient-reported outcomes after starting OAD monotherapy; factors affecting OAD treatment distribution and self-care activities and long-term trajectory of diabetes treatment among patients with T2DM in Japan.

In this paper, we present the study design and data collected at baseline, including (1) patient characteristics and distribution of OADs by drug class prescribed as initial monotherapy by specialists and non-specialists; (2) the differences in diabetes self-care activities, adherence to self-care recommendations and education on nutrition and foot care among patients treated by specialists and non-specialists.

Methods

Study design

RESPOND (JapicCTI-163306) is an ongoing, prospective, observational cohort study designed to evaluate the real-world treatment patterns of pharmacotherapy and patient-reported outcomes after starting initial OAD monotherapy in drug-naïve patients with T2DM in Japan. The primary objectives are, first, we will evaluate the initial OAD treatment patterns and assess the baseline patient and physician characteristics associated with the choice of OAD drug class as initial monotherapy (cross-sectional phase). The OAD treatment patterns will also be assessed every 6 months over 24 months of follow-up in terms of treatment switch or addition of new drug classes (longitudinal phase). Second, we will assess patient-reported outcomes, which include adherence to recommended diabetes self-management activities using Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA) questionnaire (table 1); overall QoL using EuroQol 5-dimension 5-level (EQ-5D-5L) at baseline and over the 24-month follow-up and satisfaction levels of patients on treatment during the follow-up period using the Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (status version) and Oral Hypoglycemic Agent Questionnaire (these measures were used after the initiation of drug therapy and therefore not included in the baseline data). These parameters will also be stratified by patient demographics, clinical characteristics and baseline comorbidities. Third, we will assess HbA1c, serum lipids and blood pressure goal attainment during the 24-month follow-up according to the relevant guidelines in Japan.3 There are no restrictions on concomitant treatments during the follow-up period. No visits or examinations, laboratory tests or procedures are mandated or recommended as part of this study.

Table 1.

Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA)—questionnaire and outcomes

| SDSCA questionnaire | |||

| General diet | |||

| On how many of the last 7 days have you followed a healthy eating plan? | |||

| On an average, over the past month, how many days per week have you followed your eating plan? | |||

| Diabetes-specific diet | |||

| On how many of the last 7 days did you eat five or more servings of fruits and vegetables? | |||

| On how many of the last 7 days did you eat high-fat foods such as red meat or full-fat dairy products? | |||

| Exercise | |||

| On how many of the last 7 days did you participate in at least 30 min of physical activity? (Total minutes of continuous activity, including walking) | |||

| On how many of the last 7 days did you participate in a specific exercise session (such as swimming, walking, biking) other than what you do around the house or as part of your work? | |||

| Blood glucose testing | |||

| On how many of the last 7 days did you test your blood glucose? | |||

| On how many of the last 7 days did you test your blood glucose the number of times recommended by your healthcare provider? | |||

| Foot care | |||

| On how many of the last 7 days did you check your feet? | |||

| On how many of the last 7 days did you inspect the inside of your shoes? | |||

|

Self-care activity (range: 0–7 days) |

Diabetes specialist n=563 |

Non-specialist n=768 |

P value* |

| General diet | 2.8 (2.3) | 2.8 (2.4) | 0.851 |

| Diabetes-specific diet | 3.9 (1.4) | 3.9 (1.4) | 0.304 |

| Exercise | 2.2 (2.1) | 1.9 (2.1) | 0.013 |

| Blood glucose testing | 0.1 (0.6) | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.471 |

| Foot care | 1.0 (1.9) | 0.8 (1.7) | 0.073 |

All data presented as mean (SD).

Higher scores indicate better adherence to self-care activities.

*P value calculated using Welch’s t-test.

Setting

Eligible patients were enrolled between June 2016 and May 2017 at 174 sites in Japan. Patients will be followed for a period of up to 24 months; data were collected at baseline, with ongoing follow-up data to be collected at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months (table 2). Physicians who are routinely involved in the care and treatment of patients with T2DM were targeted for recruitment. A diabetes specialist was defined as a physician certified as specialist for diabetes by the JDS. A non-specialist was defined as any other physician, including a specialist in other therapeutic areas.

Table 2.

Data collection at baseline and 6, 12, 18 and 24 months

| Baseline data collection | Follow-up data collection* | |

| Site and investigator characteristics | ✓ | – |

| Center type (clinic, hospital) | ||

| Physician (diabetes specialist, non-diabetes specialist) | ||

| Informed consent form | ✓ | – |

| Demographics | ✓ | – |

| Gender | ||

| Age | ||

| Living status | ||

| Education status | ||

| Employment status | ||

| Comorbidities | ✓ | ✓ |

| Co-medications | ✓ | ✓ |

| Vital statistics | ||

| Blood pressure | ✓ | ✓ |

| Weight | ✓ | ✓ |

| Height | ✓ | – |

| Body mass index | ✓ | – |

| Pregnancy status | ✓ | – |

| Risk factors | ✓ | – |

| Alcohol use | ||

| Smoking status | ||

| Laboratory test results | ||

| Blood test results (HbA1c, blood glucose, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, C reactive protein, albumin, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, eGFR, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C and TG) | ✓ Medical record (most recent results available for the past 6 months prior to the enrollment date) |

✓ HbA1c, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C and TG only |

| Urine test results (protein, albumin, creatinine) | ||

| Patient-reported outcome questionnaires | ||

| EQ-5D-5L | ✓ | ✓ |

| DTSQ | – | ✓ |

| OHA-Q | – | ✓ |

| SDSCA | ✓ | ✓ |

| HbA1c target | ✓ | – |

*The date of the closest laboratory test or vital assessment occurring on or nearest the prespecified assessment time point (eg, 6 months) will be selected.

DTSQ, Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol 5-dimension 5-level; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; OHA-Q, Oral Hypoglycemic Agent Questionnaire; SDSCA, Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

Participants

Drug-naïve Japanese patients with T2DM (ie, never treated with pharmacological therapy for T2DM) ≥20 years of age who were newly initiating OAD monotherapy were enrolled. Enrolled patients were required to be able and willing to provide written informed consent and respond to questionnaires in Japanese. Patients with type 1 diabetes, gestational diabetes or any other form of secondary diabetes and those pregnant or lactating were excluded from the study. Patients participating in another interventional clinical trial at the time of enrollment or during the 3 months preceding enrollment or who were planning to participate in another clinical trial were also excluded.

Data source/measurements

Data were obtained from patient medical records and paper-based surveys of patients and physicians. Treatment patterns were recorded in the medication log/records over the study period. The study sites were responsible for entering extracted patient data into a secure internet-based electronic data capture system via the electronic case report form.

Bias

To minimize selection bias, a broad eligibility criterion was selected. No imputation was performed for missing data.

Study size

A sample size of 1500 participants was considered adequate, assuming an annual attrition rate of 15%. Overall, the plan was to enroll at least 50 patients initiated on monotherapy with an OAD that is reportedly used with relatively low frequency in Japan (eg, thiazolidinediones and glinides).16

Statistical methods for the baseline analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed for data collected at baseline, including demographics and clinical characteristics, treatment patterns and self-care activities. Continuous variables were reported as mean (SD) or median (IQR), where appropriate.

Treatment distributions were compared between specialists and non-specialists using the Fisher’s exact test after stratification by tertiles of age (<54, ≥54‒<66 and ≥66 years); body mass index (BMI; <23.8, ≥23.8‒<27.6 and ≥27.6 kg/m2) and HbA1c levels (<7.0%, ≥7.0%–<8.2%, ≥8.2%).

Total scores on self-care activity assessed by SDSCA questionnaire were compared between patients visiting a specialist or non-specialist using the Welch’s t-test. The proportions of patients responding to the subscales (diet, exercise and receiving education from healthcare providers on diet and foot care) of the SDSCA questionnaire categorized by their visit to a specialist versus non-specialist were compared using Fisher’s exact test. P value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS V.9.2 or higher (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics at baseline

Overall, 1506 patients were enrolled at 174 sites in Japan, and 1485 patients formed the analysis population (online supplemental table 1). Of these, 617 patients were treated by a specialist and 868 by a non-specialist. The mean (SD) age of patients in the analysis population was 59.7 (13.3) years, and 61.8% were men. The mean (SD) age of patients treated by non-specialists was higher (62.7 (12.8) years) than that of those treated by specialists (55.6 (12.8) years) (table 3). The baseline characteristics were similar among patients treated by specialists and by non-specialists. However, a higher proportion of patients with diabetic complications (19.9% vs 8.4%) and stage G1 chronic kidney disease (CKD) (39.3% vs 22.8%) were being treated by specialists versus non-specialists. Conversely, a higher proportion of patients with comorbid cardiovascular disease (8.9% vs 2.3%), dyslipidemia (64.1% vs 48.6%), hypertension (60.6% vs 37.9%) and stage G2 or higher CKD were treated by non-specialists versus specialists. The mean (SD) duration of T2DM was 0.9 (1.9) years, and the mean (SD) HbA1c level was 8.1% (1.9%). The mean (SD) duration of T2DM and the mean (SD) HbA1c level were similar among patients treated by specialists versus non-specialists (table 3). Baseline EQ-5D-5L scores did not differ in patients with versus without diabetic complication; however, QoL was significantly reduced in patients with versus without cardiovascular disease (p<0.001; online supplemental figure 1).

Table 3.

Patient demographics and characteristics at baseline

| All patients N=1485 |

Diabetes specialist n=617 | Non-specialist n=868 | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 59.7 (13.3) | 55.6 (12.8) | 62.7 (12.8) |

| Female, n (%) | 567 (38.2) | 226 (36.6) | 341 (39.3) |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 25.5 (23.0‒28.6) | 25.6 (23.0‒28.8) | 25.4 (23.0‒28.6) |

| ≥25, n (%) | 813 (54.7) | 345 (55.9) | 468 (53.9) |

| Disease duration (years), mean (SD) | 0.9 (1.9) | 0.8 (1.8) | 0.9 (1.9) |

| Baseline HbA1c (%), mean (SD) | 8.1 (1.9) | 8.4 (1.9) | 7.9 (1.8) |

| Target HbA1c (%), mean (SD) | 6.5 (0.5) | 6.7 (0.6) | 6.4 (0.4) |

| Classification in CKD stage by eGFR, n (%), n=1250* | |||

| G1 | 369 (29.5) | 199 (39.3) | 170 (22.8) |

| G2 | 687 (55.0) | 255 (50.4) | 432 (58.1) |

| G3a | 143 (11.4) | 46 (9.1) | 97 (13.0) |

| G3b | 36 (2.9) | 5 (1.0) | 31 (4.2) |

| G4 | 11 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 10 (1.3) |

| G5 | 4 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.5) |

| Diabetic complications, n (%) | 196 (13.2) | 123 (19.9) | 73 (8.4) |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 91 (6.1) | 14 (2.3) | 77 (8.9) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 856 (57.6) | 300 (48.6) | 556 (64.1) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 760 (51.2) | 234 (37.9) | 526 (60.6) |

*Number of patients with available eGFR data.

BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin.

bmjdrc-2020-001361supp001.pdf (248.5KB, pdf)

OAD treatment distribution and factors associated with choice of OAD class

Overall, the majority of patients were prescribed DPP-4Is (55.9%; specialist vs non-specialist, 54.1% (334/617) vs 57.1% (496/868)), followed by SGLT2Is (18.8%; 13.9% (86/617) vs 22.2% (193/868)), metformin (16.0%; 20.3% (125/617) vs 12.9% (112/868)) and other OADs (<5% individually in both groups) (figure 1A, online supplemental table 2). A significantly higher proportion of patients aged ≥54‒<66 years (21.6% (43/199) vs 14.0% (38/272), p<0.05) with higher BMI (≥23.8 kg/m2; ≥23.8‒<27.6 kg/m2, 21.6% (46/213) vs 12.8% (36/281), p<0.05; ≥27.6 kg/m2, 26.4% (53/201) vs 16.7% (49/294), p<0.01) and lower HbA1c (<7%, 21.0% (29/138) vs 8.4% (27/320), p<0.001) were prescribed metformin by specialists versus non-specialists (figure 1B). Regardless of age, BMI and HbA1c strata, DPP-4Is were the most commonly prescribed OAD by both specialists and non-specialists. However, a significantly higher proportion of patients aged ≥66 years (79.2% (118/149) vs 65.5% (253/386), p<0.01) were prescribed DPP-4Is by specialists versus non-specialists (figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Treatment distribution of OADs as first-line monotherapy between diabetes specialists and non-specialists and (B) treatment distribution of OADs as first-line monotherapy between diabetes specialists and non-specialists stratified by age, BMI and HbA1c levels at baseline. *P<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. Significantly higher compared with another physician category (Fisher’s exact test). BMI, body mass index; DPP-4I, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; MET, metformin; OAD, oral antidiabetic drug; SGLT2I, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor; SU, sulfonyl urea.

In all age groups, a significantly higher proportion of patients were prescribed SGLT2Is by non-specialists versus specialists (<54 years, 33.3% (70/210) vs 23.8% (64/269), p<0.05; ≥54‒<66 years, 22.4% (61/272) vs 9.0% (18/199), p<0.001; ≥66 years, 16.1% (62/386) vs 2.7% (4/149), p<0.001). A significantly higher proportion of patients with BMI <27.6 kg/m2 (<23.8 kg/m2, 12.8% (37/290) vs 1.5% (3/203), p<0.001; ≥23.8‒<27.6 kg/m2, 19.9% (56/281) vs 12.7% (27/213), p<0.05) were prescribed SGLT2Is by non-specialists versus specialists. In addition, a significantly higher proportion of patients with higher HbA1c (≥8.2%, 24.9% (58/233) vs 13.2% (33/250), p<0.01) were prescribed SGLT2Is by non-specialists versus specialists. The prescription of SGLT2Is by specialists for patients with lower BMI (<23.8 kg/m2) was negligible (1.5% (3/203)), whereas almost three-quarters of patients in this stratum were prescribed DPP-4Is (71.4% (145/203)) (figure 1B).

Other OADs were prescribed to a significantly higher proportion of patients aged <54 years (13.0% (35/269) vs 4.3% (9/210), p<0.01) and with higher HbA1c levels (≥8.2%, 13.6% (34/250) vs 7.3% (17/233), p<0.05) by specialists versus non-specialists. The number of patients visiting the non-specialist physicians decreased with increasing HbA1c levels and vice versa (figure 1B).

SDSCA measurement outcomes

Baseline SDSCA domain scores (general diet, diabetes-specific diet and blood glucose testing) and scores for foot care were numerically low and comparable between patients treated by specialists and non-specialists (table 1).

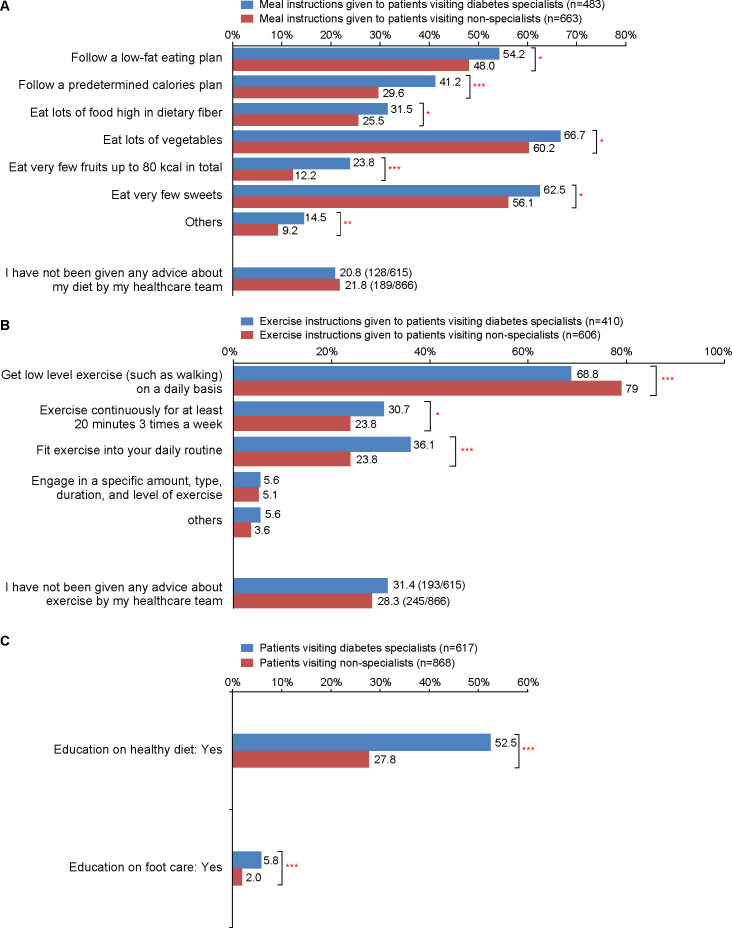

About one-fifth of the patients visiting specialists (20.8% (128/615)) and non-specialists (21.8% (189/866)) did not receive any advice about diet from their healthcare team. Among patients who received guidance on diet in both groups, approximately only 50%–60% followed the self-care recommendations for low-fat diet, more vegetable consumption and very few sweets consumed. Recommendations for a predetermined calorie plan, followed by high dietary fiber consumption, few fruits with ≤80 kcal and others were adhered to by a lower proportion of patients in both groups (range: specialist vs non-specialist, 14.5%–41.2% vs 9.2%–29.6%, respectively). However, the proportion of patients who followed the self-care recommendations for diet was significantly higher in the group treated by specialists versus non-specialists (p<0.05 for all diet-related items) (figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients adhering to self-care recommendations: (A) diet subscales using the SDSCA questionnaire, (B) exercise subscales using the SDSCA questionnaire and (C) education from healthcare providers on healthy diet and foot care. *P<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. Fisher’s exact test. SDSCA, Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities.

About one-third of the patients visiting specialists (31.4% (193/615)) and non-specialists (28.3% (245/866)) did not receive any advice about exercise from their healthcare team. Among those who received guidance on exercise in both groups, a greater majority (about 70%) followed the self-care recommendations of low-level exercise (eg, walking). Recommendations for continuous exercise for at least 20 min 3 times per week, including exercise in their daily regimen, engaging in specific amount, type, duration and level of exercise, and others were adhered to by a lower proportion of patients in both groups (range: specialist vs non-specialist, 5.6%–36.1% vs 3.6%–23.8%). However, the proportion of patients who followed the self-care recommendations for exercise was significantly higher in the group treated by specialists versus non-specialists (p<0.05 for continuous exercise for at least 20 min 3 times per week and including exercise in their daily regimen), except for low-level exercise, which was significantly higher among those visiting the non-specialist (figure 2B).

A significantly higher proportion of patients receiving treatment from specialists compared with non-specialists were educated on nutrition (52.5% (324/617) vs 27.8% (241/868), p<0.001). The proportion of patients educated on foot care was quite lower than that of patients educated on nutrition, and yet this was significantly higher among patients receiving treatment from specialists versus non-specialists (5.8% (36/617) vs 2.0% (17/868), p<0.001) (figure 2C).

Discussion

This study adds to the body of knowledge describing treatment patterns and self-care activity among drug-naïve patients with T2DM who newly initiate OAD monotherapy in Japan. Of note, a higher proportion of patients with dyslipidemia, hypertension, cardiovascular disease and stage G2 or higher CKD were treated by non-specialists than diabetes specialists. This may be attributed to the tendency of patients with these comorbidities to consult cardiologists, nephrologists or physicians with other specialties, all of whom are regarded as non-specialists for diabetes in this study. Another explanation is that these patients may have already been treated for such comorbidities by non-specialists before the diagnosis of T2DM, and if necessary, antidiabetic therapy may have been initiated in addition to existing cardiovascular risk control in the same setting. Conversely, a higher proportion of those with diabetic complications were treated by diabetes specialists rather than non-specialists. This may be attributed to clinical practice in which early stages of microvascular complications, including retinopathy, neuropathy and nephropathy are usually managed by diabetes specialists. Baseline EQ-5D-5L scores did not differ in patients with or without diabetic complications; however, QoL was significantly reduced in patients with cardiovascular disease.

Trends in prescription pattern

The landscape for T2DM treatment in Japan has evolved over the past decade, with the use of insulin monotherapy decreasing from 12.2% to 3.6% and that of OADs increasing from 51.8% to 64.8% between 2008 and 2018.17 However, with the introduction of DPP-4Is in 2009, the use of sulfonylureas decreased18 and that of DPP-4Is dramatically increased, and thus DPP-4Is became the most commonly prescribed agent in Japan in the first month of T2DM treatment by 2011.19 Similar results were observed in two further studies (two repeated cross-sectional studies) conducted at a single center in Japan that examined changes in prescription patterns between 2001 and 2013.20

The results of the current study are generally aligned with these reports. We observed that DPP-4Is were the most commonly prescribed OAD by both specialists (54.1%) and non-specialists (57.1%) to patients enrolled in this study regardless of age, BMI and HbA1c strata. Of note, a significantly higher proportion of older patients aged ≥66 years were prescribed DPP-4Is by specialists versus non-specialists.

SGLT2Is were the second most prescribed OAD as initial monotherapy, with a significantly higher proportion of patients in all age subgroups, subgroups with BMI <27.6 kg/m2 and the subgroup of the highest HbA1c tertile (≥8.2%) treated by non-specialists rather than specialists. The easily observable response, if any, to SGLT2Is treatment (eg, decrease in weight, decrease in blood pressure) and/or relatively lower risk of hypoglycemia on once-daily monotherapy compared with combination therapy21 may account for the higher prescription rate by non-specialists. Of note, the difference of SGLT2Is prescription rate between the non-specialists and specialists increased in the older age groups. Higher awareness among specialists on the risk of SGLT2I-associated adverse events in the elderly, including sarcopenia,22 may be the reason for the relatively low prescription rate among specialists. If this assumption is correct, the awareness of this risk among non-specialists may need to be raised. Similarly, the prescription of SGLT2Is by specialists for patients in the lowest BMI tertile (<23.8 kg/m2) was extremely rare (1.5%) in contrast to the higher rate (12.8%, p<0.001) by non-specialists. These differences may be attributed to the specialists showing better compliance with recommendations for SGLT2I prescription, which emphasizes the importance of individualization regarding the potential adverse effects preferentially manifesting in elderly patients or patients at risk of ketoacidosis with lower BMI.23

Metformin was prescribed as initial OAD monotherapy in 16.0% of patients in this study. The lower prescription rate compared with the figures reported for Western countries10 11 could be due to, at least in part, (1) the Japanese guideline, which does not specify the particular first-line OAD in contrast to the guidelines in the USA and the European Union where metformin is recommended as the first-line therapy along with lifestyle modifications for most cases on initial treatment3–5; (2) a rapid increase in the prescription of DPP-4Is as an initial monotherapy, which coincided with the delayed approval of metformin 2250 mg as the highest daily dosage in Japan—limited to 750 mg until 2010 due to concerns of lactic acidosis and (3) the unique situation in Japan where an extended release formulation of metformin is still unavailable despite the preference for drugs requiring less frequent daily administration. A significantly higher proportion of patients aged ≥54–<66 years with higher BMI (≥23.8 kg/m2) and lower HbA1c (<7%) were prescribed metformin by specialists versus non-specialists, showing that more specialists prescribe metformin taking these clinical features into account.

Although results cannot be directly compared due to differences in study design, definitions and stratification, a retrospective observational study (2008–2013) using a hospital database in Japan reported that initial HbA1c levels did affect the OAD class prescribed.16 In a more recent web-based survey of physicians across eight selected regions in Japan, it was observed that for both specialists and non-specialists, the choice of DPP-4Is was influenced by HbA1c levels, postprandial glucose (PPG)-lowering effect and a low risk of hypoglycemia, whereas the choice of metformin was influenced by improvement in insulin resistance, low cost, low risk of hypoglycemia and PPG-lowering and HbA1c-lowering effects.24 In addition, a number of other factors, such as risk of gastrointestinal side effects, improvement in insulin resistance, effect on glucagon, protection of β-cell function, frequency of administration and body weight led to a considerable difference (>10%) in the choice of OAD for treatment-naïve patients between specialists and non-specialists.24

Interestingly, results from a nation-wide, cross-sectional survey in Japan reported that HbA1c levels in patients treated by non-specialists were significantly lower than in those treated by specialists.25 This was similar to our study where the number of patients visiting non-specialists decreased with increasing HbA1c levels and vice versa.

Adherence to recommended diabetes self-management activities

The chronic and progressive nature of T2DM presents continued challenges in the form of long-term macrovascular and microvascular complications; however, such complications can be delayed or prevented with strict metabolic control.26 In such a scenario, diabetes self-care, which requires the patient to make dietary and lifestyle modifications with the support of healthcare providers,26 is an important aspect of disease management and improving the overall well-being of patients.27 It is critical for healthcare providers to educate patients on self-care activities on a continuing basis.26

A study conducted in Australia reported that the SDSCA measure was the only self-management tool (besides two other psychological adjustment tools), among 37 psychometric measurement tools, that met all rigorous psychometric appraisal criteria.28 Furthermore, a Japanese translation of the SDSCA questionnaire confirmed its validity and reliability for the evaluation of self-care activities among Japanese patients with T2DM.29 In this study, patients treated by diabetes specialists versus non-specialists had significantly higher exercise scores on the SDSCA questionnaire at baseline. However, about one-fifth of the patients visiting either specialists or non-specialists did not receive any advice about diet from their healthcare team, suggesting a potential for improvement in this domain. Among patients who received guidance on diet in both groups, approximately only 10%–60% followed the subscales of self-care diet recommendations. However, the proportion of patients who followed all the self-care recommendations for diet was significantly higher in the group treated by specialists compared with the group treated by non-specialists.

Similarly, about one-third of the patients visiting specialists and non-specialists did not receive any advice about exercise by their healthcare team, suggesting that there was also a potential for improvement in this domain. Among those who received guidance on exercise in both groups, a greater majority (about 70%) preferred to follow a low-level exercise (eg, walking) regimen. Other subscale recommendations were adhered to by a non-ideal proportion of patients in both groups (3.6%–36.1%). However, the proportion of patients who followed the self-care recommendations for exercise was significantly higher in the group treated by specialists versus non-specialists for the subscales continuous exercise for at least 20 min 3 times per week and including exercise in their daily regimen. Similarly, a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving treatment from specialists compared with non-specialists were educated on nutrition.

Previous research from Japan has suggested that self-care behavior significantly improved exercise scores after 24 weeks among patients using a color display method for self-monitoring of blood glucose30 and after 3 months of regular foot care intervention, which was sustained for up to 1 year.31 However, education on foot care was rarely implemented in this study and yet was significantly higher among patients receiving treatment from specialists versus non-specialists.

As with all observational studies, limitations include non-generalizability of results and multiplicity of testing. Furthermore, as this initial analysis of the data was cross-sectional, we can only infer association and not causation of all outcomes.32 There may also exist a recall bias commonly observed with patient-reported data.33 Conversely, some of the strengths of this prospective observational study include providing important information related to patient and physician factors associated with choice of OAD and adherence to self-care activities for up to 24 months following initiation of therapy in a real-world setting.

Conclusion

This study suggests that the use of newer OAD is common across a broad range of clinical characteristics in patients with T2DM who newly initiated monotherapy in Japan. During the following course of treatment, patient-related (age, BMI and HbA1c) and physician-related (specialists or non-specialists) factors could affect the choice of drug classes prescribed for later-line therapy in patients with T2DM in Japan. Moreover, the extent and quality of diabetes education provided by diabetes specialists versus non-specialists could differ and subsequently affect patient adherence to self-care activities. The follow-up manuscript will present the longitudinal phase data, including the changes in treatment patterns over time and the influence of patient demographic and clinical characteristics and education on treatment outcome.

Acknowledgments

This study was performed by CMIC-PMS Co., Ltd. under the guidance and approval of the Sponsor. Editorial support was provided by Cactus Life Sciences (part of Cactus Communications). The authors would like to thank Drs. Jun-ichi Eiki, Akira Nagumo, Machiko Abe and Atsushi Tajima of MSD K.K., Tokyo, Japan, for their helpful suggestions and assistance in manuscript revision.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the study design, the interpretation of the results and the critical review of the manuscript. DY, KT, KI, ST and YS were involved in the conception of the study and drafted the manuscript. DY and KT were responsible for data analysis.

Funding: This study was funded by MSD K.K., Tokyo, Japan.

Competing interests: DY has received personal fees from MSD during the conduct of the study. His relevant financial activities outside the submitted work are grants and personal fees from Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim and Novo Nordisk and grants from Ono, Taisho Toyama, Takeda, Terumo and Arkray. HH has received personal fees and non-financial support from MSD during the conduct of the study and grants from Novartis outside the submitted work. TK has received consulting fees from MSD for the work under consideration for publication. His relevant financial activities outside the submitted work are contract research funds from AstraZeneca and Takeda; joint research funds from Daiichi Sankyo; grants from Astellas, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Kissei, Mitsubishi Tanabe, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Ono, Sanofi, Sumitomo Dainippon, Taisho and Takeda and fees for consulting and/or lectures from Abbott, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cosmic, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Fujifilm, Johnson & Johnson, Kissei, Kowa, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Medical Review, Medical View, Medscape Education, Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Mitsubishi Tanabe, MSD, Musashino Foods, Nipro, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Ono, Sanofi, Sanwa Kagaku, Sumitomo Dainippon, Taisho, Takeda and Terumo. He has also been an Endowed Chair for Asahi Mutual Life Insurance, Boehringer Ingelheim, Kowa, Mitsubishi Tanabe, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Ono and Takeda. HO has received personal fees from MSD during the conduct of the study. IS has received grants and personal fees from MSD during the conduct of the study. His relevant financial activities outside the submitted work are grants and personal fees from Astellas, AstraZeneca, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Ono, Sanofi and Takeda; grants from Daiichi Sankyo, Kissei, Kowa, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Mochida, Novartis, Rohto, Shionogi, Sumitomo Dainippon, Teijin and Terumo and personal fees from Kowa, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim and Sanwa Kagaku. HW has received grants and personal fees from MSD during the conduct of the study. His relevant financial activities outside the submitted work are grants and personal fees from Astellas, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Ono, Sanofi, Sanwa Kagaku, Sumitomo Dainippon and Takeda; grants from Johnson & Johnson, Teijin, Yakult, Kissei, Kowa, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Pfizer and Taisho Toyama and personal fees from Fujifilm, Terumo and AstraZeneca. KI was employed by Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, New Jersey, USA, during the conduct of this study and owns stock. YS has received personal fees from MSD during the conduct of the study. His relevant financial activities outside the submitted work are grants and personal fees from Novo Nordisk and Taisho Toyama; grants from Arkray Marketing, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ono, Sumitomo Dainippon and Terumo and personal fees from Kao, Nippon Becton Dickinson, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Taisho and Takeda. KT and ST are employees of MSD K.K. and own stock.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by Toukeikai Kitamachi Clinic ethical review board (Approval number MSD04820) and was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, New Jersey, USA’s data sharing policy, including restrictions, is available at http://engagezone.msd.com/ds_documentation.php. Requests for access to the study data can be submitted through the EngageZone site or via email to dataaccess@merck.com.

References

- 1.International Diabetes Federation Diabetes atlas, 2019. Available: https://www.diabetesatlas.org/en/ [Accessed 13 Feb 2020].

- 2.Seino Y, Kuwata H, Yabe D. Incretin-based drugs for type 2 diabetes: focus on East Asian perspectives. J Diabetes Investig 2016;7:102–9. 10.1111/jdi.12490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haneda M, Noda M, Origasa H, et al. Japanese clinical practice guideline for diabetes 2016. Diabetol Int 2018;9:1–45. 10.1007/s13340-018-0345-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Japan Diabetes Society Treatment guide for diabetes 2016-2017. Available: http://www.fa.kyorin.co.jp/jds/uploads/Treatment_Guide_for_Diabetes_2016-2017.pdf [Accessed 13 Feb 2020].

- 5.Davies MJ, D'Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2018;41:2669–701. 10.2337/dci18-0033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Diabetes Association 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes–2019. Diabetes Care 2019;42:S90–102. 10.2337/dc19-S009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neville SE, Boye KS, Montgomery WS, et al. Diabetes in Japan: a review of disease burden and approaches to treatment. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2009;25:705–16. 10.1002/dmrr.1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kubota A, Maeda H, Kanamori A, et al. Efficacy and safety of sitagliptin monotherapy and combination therapy in Japanese type 2 diabetes patients. J Diabetes Investig 2012;3:503–9. 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2012.00221.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito H, Shinozaki M, Nishio S, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors in the pipeline for the treatment of diabetes mellitus in Japan. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2016;17:2073–84. 10.1080/14656566.2016.1232395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Overbeek JA, Heintjes EM, Prieto-Alhambra D, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus treatment patterns across Europe: a population-based multi-database study. Clin Ther 2017;39:759–70. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montvida O, Shaw J, Atherton JJ, et al. Long-term trends in antidiabetes drug usage in the U.S.: real-world evidence in patients newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2018;41:69–78. 10.2337/dc17-1414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pantalone KM, Hobbs TM, Wells BJ, et al. Changes in characteristics and treatment patterns of patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes in a large United States integrated health system between 2008 and 2013. Clin Med Insights Endocrinol Diabetes 2016;9:23–30. 10.4137/CMED.s39761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishimura R, Kato H, Kisanuki K, et al. Treatment patterns, persistence and adherence rates in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Japan: a claims-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e025806. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirata Y. Systems for the treatment of diabetes in Japan. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1994;24 Suppl:S229–32. 10.1016/0168-8227(94)90254-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care 2000;23:943–50. 10.2337/diacare.23.7.943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanabe M, Motonaga R, Terawaki Y, et al. Prescription of oral hypoglycemic agents for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a retrospective cohort study using a Japanese hospital database. J Diabetes Investig 2017;8:227–34. 10.1111/jdi.12567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Japan Diabetes Clinical Data Management study group Basic summary data, 2018. Available: http://jddm.jp/data/index-2018/ [Accessed 13 Feb 2020].

- 18.Arai K, Matoba K, Hirao K, et al. Present status of sulfonylurea treatment for type 2 diabetes in Japan: second report of a cross-sectional survey of 15,652 patients. Endocr J 2010;57:499–507. 10.1507/endocrj.K09E-366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohro T, Yamazaki T, Sato H, et al. Trends in antidiabetic prescription patterns in Japan from 2005 to 2011. Int Heart J 2013;54:93–7. 10.1536/ihj.54.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujibayashi K, Hayashi M, Yokokawa H, et al. Changes in antidiabetic prescription patterns and indicators of diabetic control among 200,000 patients over 13 years at a single institution in Japan. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2016;8:72. 10.1186/s13098-016-0187-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Baar MJB, van Ruiten CC, Muskiet MHA, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors in combination therapy: from mechanisms to clinical considerations in type 2 diabetes management. Diabetes Care 2018;41:1543–56. 10.2337/dc18-0588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yabe D, Nishikino R, Kaneko M, et al. Short-term impacts of sodium/glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors in Japanese clinical practice: considerations for their appropriate use to avoid serious adverse events. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2015;14:795–800. 10.1517/14740338.2015.1034105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Japan Diabetes Society Recommendation on the proper use of SGLT2 inhibitors: revision on 6 August 2019 (in Japanese). Available: http://www.fa.kyorin.co.jp/jds/uploads/recommendation_SGLT2.pdf [Accessed 13 Feb 2020].

- 24.Murayama H, Imai K, Odawara M. Factors influencing the prescribing preferences of physicians for drug-naive patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the real-world setting in Japan: insight from a web survey. Diabetes Ther 2018;9:1185–99. 10.1007/s13300-018-0431-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arai K, Hirao K, Matsuba I, et al. The status of glycemic control by general practitioners and specialists for diabetes in Japan: a cross-sectional survey of 15,652 patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2009;83:397–401. 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shrivastava SR, Shrivastava PS, Ramasamy J. Role of self-care in management of diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Metab Disord 2013;12:14. 10.1186/2251-6581-12-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodall TA, Halford WK. Self-management of diabetes mellitus: a critical review. Health Psychol 1991;10:1–8. 10.1037/0278-6133.10.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eigenmann CA, Colagiuri R, Skinner TC, et al. Are current psychometric tools suitable for measuring outcomes of diabetes education? Diabet Med 2009;26:425–36. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02697.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daitoku M, Honda I, Okumiya A, et al. Validity and reliability of the Japanese translated “the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities measure”. J Japan Diabetes Soc 2006;49:1–9. 10.11213/tonyobyo.49.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishimura A, Wasa M, Harashima S, et al. Influence of flash glucose monitoring on diabetes self-management: a before-after study. J Japan Diabetes Soc 2018;61:171–80. 10.11213/tonyobyo.61.171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daitoku M, Egawa T, Fujiwara Y, et al. Effects of foot care intervention on self-care behavior in the patients with diabetes mellitus. J Japan Diabetes Soc 2007;50:163–72. 10.11213/tonyobyo.50.163 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sedgwick P. Cross sectional studies: advantages and disadvantages. BMJ 2014;348:g2276 10.1136/bmj.g2276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmier JK, Halpern MT. Patient recall and recall bias of health state and health status. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2004;4:159–63. 10.1586/14737167.4.2.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjdrc-2020-001361supp001.pdf (248.5KB, pdf)