Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: amplified in breast cancer 1, biomarker, breast cancer, meta-analysis, prognosis

Abstract

Purpose:

Amplified in breast cancer 1 (AIB1) expression is known to be involved in the initiation and progression of malignant breast cancer (BC), but its prognostic role remains uncertain. This meta-analysis assessed reported studies to evaluate this relationship.

Methods:

Electronic databases were systematically reviewed to collect eligible studies using pre-established criteria. Hazard ratios (HRs) or odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were pooled to estimate the impact of AIB1 protein expression on overall survival (OS) and clinicopathologic properties of BC cases.

Results:

Nine eligible studies, including 6774 patients, were finally assessed by the current clinical meta-analysis. AIB1 positivity correlated with reduced OS (pooled HR = 1.409, 95% CI 1.159–1.714, P = .001). AIB1 overexpression also impacted prognosis as shown by univariate (pooled HR = 1.420, 95% CI 1.154–1.747, P = .001) and multivariate (pooled HR = 1.446, 95% CI 1.099–1.956; P = .009) analyses. Notably, subgroup analyses also revealed that AIB1 overexpression was associated with poor OS in some subgroups, such as ER-positive group (pooled HR = 1.511, 95% CI 1.138–2.006, P = .004), ER-positive without tamoxifen administration group (pooled HR = 2.338, 95% CI 1.489–3.627, P < .001), and premenopausal women group (pooled HR = 1.715, 95% CI 1.231–2.390, P = .001). Additionally, high AIB1 protein levels were associated with HER2 positivity (pooled OR = 0.331, 95% CI 0.245–0.448; P < .001), poorly differentiated histological grade (pooled OR = 0.377, 95% CI 0.317–0.448; P < .001), high Ki67 (pooled OR = 0.501, 95% CI 0.410–0.612; P < .001), presence of lymph node metastases (pooled OR = 0.866, 95% CI 0.752–0.997; P = .045), and absence of progesterone receptor (pooled OR = 1.447, 95% CI 1.190–1.759; P < .001).

Conclusions:

This analysis demonstrated that AIB1 overexpression is related to aggressive phenotypes and unfavorable clinical outcomes in BC, and might involve in tamoxifen resistance. AIB1 may be a new prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target in BC.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) represents a frequently diagnosed malignancy, with a global yearly incidence of approximately 1.7 million. BC is also the deadliest malignancy in female patients, with 15% of total cancer deaths.[1] Although numerous available strategies, such as physical activity, quality diet, and mammography, have been used to decrease BC risk, its incidence and mortality rates steadily increase. As with other cancers, early diagnosis and prospective prognosis could alleviate patient concerns about treatment and negative beliefs regarding therapeutic complications. The introduction of effective molecular markers could facilitate early detection and, in some cases, ameliorate access to treatment. For example, vesicle-associated membrane protein 8[2] and amplified in breast cancer 1 (AIB1)[3] have been proposed; however, their respective contributions are unclear. Thus, approaches to increase the efficacy of BC treatment still need to be considered.

AIB1, also termed SRC-3, NCOA3, ACTR, pCIP, RAC3, or TRAM1, has been shown to regulate tumor formation and tumorigenesis in BC. As the name implies, AIB1 is found in a region commonly amplified in BC, namely, chromosome 20q13.12.[4] It is well established that AIB1 is upregulated in BC, and its overexpression is important in tumor proliferation and metastasis via many intracellular signaling pathways. Interestingly, AIB1 cannot only stimulate nuclear receptors, including estrogen (ER), androgen, and progesterone (PR) receptors, but also does interact with numerous transcription factors to alter gene expression and facilitate RNA polymerase II transcription.[5,6] However, AIB1 is well studied in tumor mechanism, but the exploration of clinical application of AIB1 is not satisfactory. Clinically, AIB1 has been associated with antagonistic effects, especially during treatment with tamoxifen, which is commonly applied in females with primary ER-positive BC.[7] And abnormal expression of AIB1 was shown to correlate with prognosis in BC.[3] Conversely, previous trials have demonstrated that AIB1 is not an independent marker of tamoxifen resistance or patient outcome.[8–11] Thus, the conclusions drawn from previous studies remain uncertain, more importantly, there is no article to systematically evaluate the prognostic value of AIB1 in BC. Therefore, a meta-analysis of the prognostic value of AIB1 in BC is required and imperative.

In the present study, a timely meta-analysis of relevant articles was carried out to evaluate AIB1's association with cumulative survival rate in patients with BC. With a relatively large sample size, it was possible to provide additional information for developing an optimal treatment for BC.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Databases and search strategy

A systematic computer-aided literature query was conducted. Available databases, including PubMed, PMC, Elsevier, Springer, Wiley, EBSCO, Science Direct, and the Web of Science, were searched by 2 independent investigators until July 2019, with “(AIB1 or “amplified in breast cancer 1”) AND (cancer or tumor or malignancy or neoplasm or carcinoma) AND (prognosis or prognostic or survival or outcome)” as key terms. In addition to screening the reference lists in the relevant literature, we also searched all alternate names of AIB1 in the initial retrieval to avoid missing relevant articles. The current meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.[12] The included studies were limited to those published in English.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The eligibility criteria comprised: inclusion of groups of patients with AIB1-positive or AIB1-negative disease, with valid overall survival (OS) information obtained by comparing these 2 groups; well-examined AIB1 protein expression in the BC tissue using effective antibodies; prognostic information from any subgroup analyses derived from a prearranged cutoff value; more than 100 patients involved; and all patients received surgical treatment but with preoperative and postoperative treatment not limited. Letters, editorials, conference abstracts, case reports, reviews, and comment articles were excluded.

2.3. Data extraction and quality assessment

Two investigators independently screened all included studies identified in the literature searches, and extracted relevant information with a predefined template: authors, publication date, country, patient age, sample size, AIB1 protein detection technique, follow-up duration, inclusion period, cutoff value(s), analysis technique, survival outcomes, hazard ratios (HR), ER status, menstrual status, TNM stage and other indicated clinical characteristics. Study quality was independently graded by 2 investigators based on the Newcastle-Ottawa scale, which assesses several scopes of the included studies such as selection, comparability, and exposure. Eligible articles showing scores above 6 points were considered to be of high quality. Discrepancies were further discussed and arbitrated by a third investigator.

2.4. Ethical approval and informed consent

This work contains no studies evaluating humans or animal models by any of the authors. As this study was a meta-analysis and did not involve contact with patients or patient information, it was not applicable for informed consent to be obtained.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Pooled analysis was carried out with STATA 14.0 (STATA Corporation, USA). HRs and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained from relevant studies or directly provided by the authors. Then, the HRs and 95% CIs were pooled to estimate the association of AIB1 protein expression with the clinical prognosis of cancer patients by the Z-test. For a more accurate estimation, we prioritized the adjusted HR in case of various coexisting analysis methods. Similarly, associations of AIB1 expression with clinicopathological properties were assessed by combining odds ratios (ORs). Cochrane's Q-statistic and I2 index were employed for assessing data heterogeneity. In case of heterogeneity (χ2 test of ph > 0.10 or I2 < 50%), a fixed effects model was utilized; otherwise, a random effects model was employed. Meta-regression and sensitivity analyses were carried out to investigate heterogeneity and stability between studies, and Egger and Begg tests were carried out for evaluating the risk of publication bias. Two-sided P < .05 indicated statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection and properties of the included articles

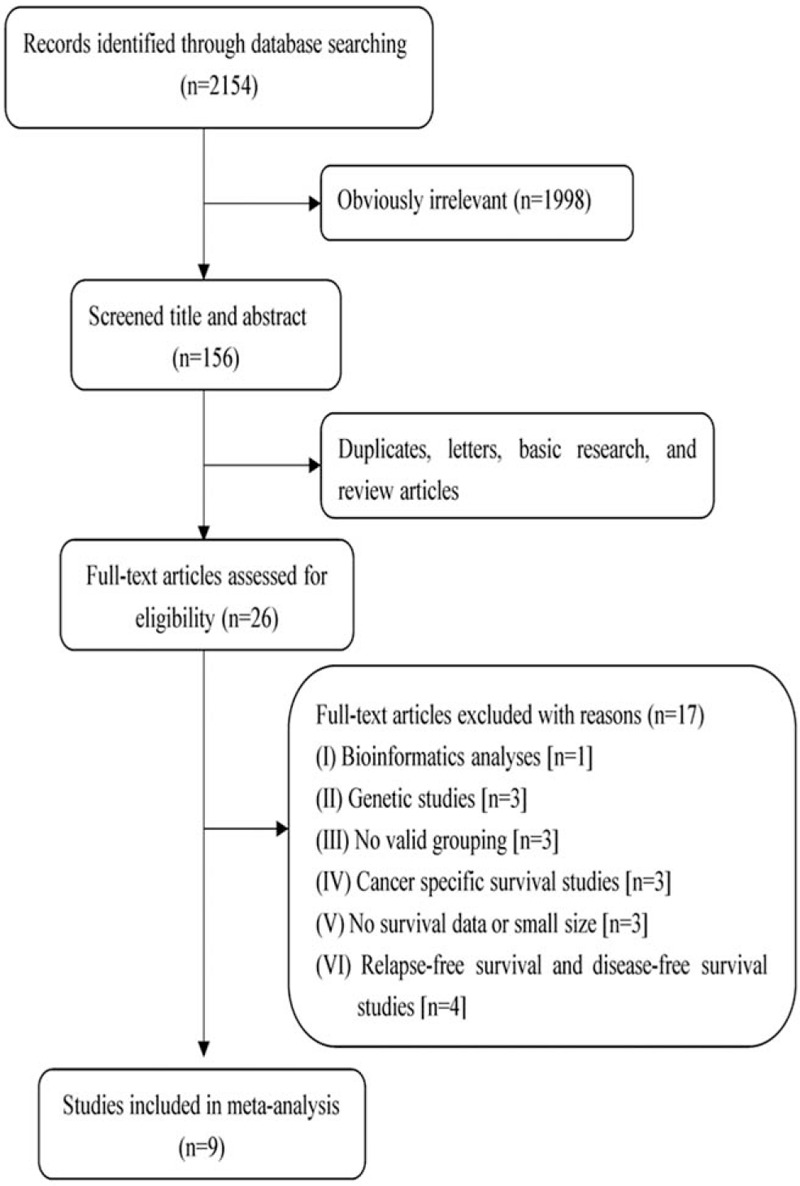

Figure 1 summarizes the precise selection process of the relevant studies. We retrieved a total of 2154 relevant publications in a preliminary literature search. After applying the abovementioned eligibility criteria, 2128 of the articles were excluded as repeated studies, reviews, letters, basic science, and so on. The remaining 26 reports were assessed in detail, and 17 were consequently discarded because of insufficient data (bioinformatics analysis [n = 1], genetic studies [n = 3], no valid grouping [n = 3], cancer-specific survival analyses [n = 3], survival data absent or small sizes [n = 3], and relapse-free survival and disease-free survival studies [n = 4]). Although the 2 studies by Alkner et al[10,13] were based on the same hospital source, both were assessed in this analysis because they included different populations. Ultimately, 9 reports were included in the present systematic meta-analysis. These eligible articles were published from 2007 to 2019, comprising 6774 patients from England,[8,14] Japan,[9] America,[15] Sweden,[10,13,16] Switzerland,[17] and Denmark.[11] All included studies enrolled women who were diagnosed with BC. Two studies included only postmenopausal women, while 3 included premenopausal women. All 9 articles reported HRs with CIs for OS determined by univariate or multivariate analysis. Of note, Alkner et al[10] provided 3 HRs for OS based on different cohorts. Nine studies performed immunohistochemical staining for detection, but had varying cutoff values for determining positive staining. All 9 articles reported follow-up end points, and only 1 study did not describe the inclusion period. Among these studies, 5 were retrospective, and the remaining were prospective. Basic information regarding the included article is shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Study selection process.

Table 1.

Characteristics of eligible studies.

| Study | Type of study | Country | Sample size | Age (years) | Detection method | Follow-up period (years) | Inclusion period | Cutoff scores (high/low) | Analysis method | OS, HR estimation | Quality score |

| Kirkegaard T (2007) | Retrospective study | England | 352 | NS | IHC | 6.45 (median) | 1983–1999 | Score ≥100∗ | Multivariate analysis | 1.62 (0.97–2.69) | 7 |

| Yamashita H (2008) | Retrospective study | Japan | 278 | 28–91 | IHC | 8 (median) | 1982–1999 | Score > 5† | Univariate analysis | 1.45 (0.79–2.7) | 6 |

| Harigopal M (2009) | Prospective study | America | 561 | NS | IHC | 30 (mean) | 1962–1979 | Score > 44.8‡ | Univariate/multivariate analysis | 1.009 (1.001–1.018) | 8 |

| Alkner S (2010) | Prospective study | Sweden | 180 | 45 (median) | IHC | 14 (median) | 1986–1991 | Score ≥5† | Univariate/multivariate analysis | 1.67 (1.02–2.74) | 7 |

| Spears M (2012) | Retrospective study | England | 1505 | NS | IHC | 9 (minimum) | 1981–1998 | Upper quartile | Univariate analysis | 1.5 (1.16–1.94) | 7 |

| Alkner S (2013) | Prospective study | Sweden | 205 | NS | IHC | 18.3 (maximum) | 1991–1994 | Score ≥5† | Univariate/multivariate analysis | 2.3 (1.3–4.2) | 8 |

| Prospective study | Sweden | 297 | NS | IHC | 21.4 (median) | 1985–1994. | Score ≥5† | Univariate analysis | 1.2 (0.6–2.4); 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 7 | |

| Burandt E (2013) | Retrospective study | Switzerland | 1944 | 62 (median) | IHC | 5.7 (mean) | NS | Score ≥4† | Univariate analysis | 1.55 (1.29–1.85) | 7 |

| Alkner S (2017) | Prospective study | Denmark | 1244 | NS | IHC | 9 (median) | 1998–2003 | Score ≥5† | Univariate/multivariate analysis | 1.25 (0.99–1.6) | 8 |

| Narbe U (2019) | Retrospective study | Sweden | 224 | 62 (median) | IHC | 26 (median) | 1980–1991 | Score = 6† | Univariate/multivariate analysis | 3 (1.1–7.8) | 8 |

3.2. Prognostic value of AIB1 expression

As shown in Table 2, the combined analysis of 11 datasets showed that AIB1 positivity was correlated with decreased OS as shown in Table 2 (pooled HR = 1.409, 95% CI 1.159–1.714; Fig. 2A). In subgroup analysis based on analysis method, univariate analysis showed shorter OS (pooled HR = 1.420, 95% CI 1.154–1.747; P = .001) (Fig. 2B) among AIB1-positive patients, and multivariate analysis confirmed poor prognosis conferred by AIB1 positivity in regard to OS (pooled HR = 1.446, 95% CI 1.099–1.956; P = .009) (Fig. 2C). Next, subgroup analyses according to adjuvant endocrine treatment, TNM stage, sample size, type of study, and research region were carried out. We found that AIB1 overexpression led to markedly decreased OS in patients with or without tamoxifen treatment (pooled HR = 1.313, 95% CI 1.137–1.515, P < .001; pooled HR = 1.907, 95% CI 1.307–2.783, P = .001, respectively) but not in patients not administered standard adjuvant therapy (pooled HR = 1.396, 95% CI 0.967–2.014, P = .075). In subgroup analysis based on TNM stage, AIB1 expression significantly affected OS among patients with stage I-II BC (pooled HR = 1.356, 95% CI 1.135–1.621, P = .001). A comparable positive correlation was observed in individuals with stage I-IV BC (pooled HR = 1.458, 95% CI 1.122–1.895, P = .005). Further, this analysis demonstrated AIB1 positivity resulted in significantly reduced OS, both in studies with less than 300 patients (pooled HR = 1.418, 95% CI 1.151–1.747, P = .001) and those assessing more than 300 cases (pooled HR = 1.330, 95% CI 1.036–1.707, P = .025). Next, this study confirmed the association of AIB1 expression with patient OS irrespective of the type of study (retrospective study, pooled HR = 1.555, 95% CI 1.357–1.783, P < .001; prospective study, pooled HR = 1.243, 95% CI 1.008–1.533, P = .042) and research region (Europe, pooled HR = 1.448, 95% CI 1.301–1.612, P < .001; others, pooled HR = 1.009, 95% CI 1.001–1.018, P = .036).

Table 2.

Meta-analysis of AIB1 overexpression and prognosis in patients with breast cancer.

| Categories | Studies (patients) | HR (95% CI) | I2 (%) | ph | Z | P |

| OS | 11 (6774) | 1.409 (1.159–1.714)∗ | 81.9 | <0.001 | 3.44 | .001 |

| Analysis method | ||||||

| Multivariate analysis | 6 (2750) | 1.446 (1.099–1.956)∗ | 77.9 | <0.001 | 2.60 | .009 |

| Univariate analysis | 10 (6392) | 1.420 (1.154–1.747)∗ | 84.7 | <0.001 | 3.31 | .001 |

| Adjuvant endocrine treatment | ||||||

| With tamoxifen | 5 (3398) | 1.313 (1.137–1.515)† | 0.0 | 0.537 | 3.72 | <.001 |

| Without tamoxifen | 2 (385) | 1.907 (1.307–2.783)† | 0.0 | 0.413 | 3.35 | .001 |

| No limitation | 4 (2991) | 1.396 (0.967–2.014)∗ | 89.2 | <0.001 | 1.78 | .075 |

| TNM stage | ||||||

| Stage II early | 4 (1982) | 1.356 (1.135–1.621)† | 3.1 | 0.377 | 3.35 | .001 |

| All stage | 7 (4792) | 1.458 (1.122–1.895)∗ | 85.6 | <0.001 | 2.82 | .005 |

| Sample size | ||||||

| <300 | 6 (1168) | 1.418 (1.151–1.747)† | 37.6 | 0.155 | 3.28 | .001 |

| >300 | 5 (5606) | 1.330 (1.036–1.707)∗ | 89.2 | <0.001 | 2.24 | .025 |

| Type of study | ||||||

| Retrospective study | 5 (4287) | 1.555 (1.357–1.783)† | 0.0 | 0.758 | 6.33 | <.001 |

| Prospective study | 6 (2487) | 1.243 (1.008–1.533)∗ | 67.0 | 0.010 | 2.04 | .042 |

| Research region | ||||||

| Europe | 9 (5935) | 1.448 (1.301–1.612)† | 22.4 | 0.244 | 6.79 | <.001 |

| Others | 2 (839) | 1.009 (1.001–1.018)† | 25.2 | 0.247 | 2.10 | .036 |

Figure 2.

Clinical meta-analysis. A, Forest plot for overall survival by AIB1 protein expression. B, Forest plot for overall survival by AIB1 protein expression in univariate analysis. C, Forest plot for overall survival by AIB1 protein expression in multivariate analysis. AIB1 = amplified in breast cancer 1.

Subgroup analyses were equally performed based on available clinic characteristics (Table 3). AIB1 positivity showed no significant association with OS in the ER-negative BC subgroup (pooled HR = 1.328, 95% CI 0.996–1.769, P = .053), but was associated with reduced OS in ER-positive BC patients (pooled HR = 1.511, 95% CI 1.138–2.006, P = 0.004). Owing to the special role of tamoxifen as a selective ER modulator, we further analyzed various ER subtypes according to treatment with tamoxifen. The OS rate was significantly lower only in ER-positive BC cases without tamoxifen administration (pooled HR = 2.338, 95% CI 1.489–3.627, P < .001). In premenopausal women, the pooled data showed that elevated AIB1 expression led to a worse OS (pooled HR = 1.715, 95% CI 1.231–2.390, P = .001); however, AIB1 expression was not significantly correlated with OS in postmenopausal women (pooled HR = 1.193, 95% CI 0.985–1.443, P = .070).

Table 3.

Meta-analysis of AIB1 prognostic role in specified breast cancer subgroups.

| Categories | Studies (patients) | HR (95% CI) | I2 (%) | ph | Z | P |

| ER status | ||||||

| Negative | 5 (507) | 1.328 (0.996–1.769)† | 0.0 | 0.830 | 1.93 | .053 |

| With tamoxifen | 3 (379) | 1.326 (0.964–1.824)† | 0.0 | 0.503 | 1.74 | .082 |

| Without tamoxifen | 2 (128) | 1.333 (0.687–2.588)† | 0.0 | 0.742 | 0.85 | .396 |

| Positive | 8 (2535) | 1.511 (1.138–2.006)∗ | 54.2 | 0.033 | 2.85 | .004 |

| With tamoxifen | 4 (1797) | 1.199 (0.999–1.440)† | 18.7 | 0.297 | 1.95 | .051 |

| Without tamoxifen | 2 (252) | 2.338 (1.489–3.672)† | 40.8 | 0.194 | 3.69 | <.001 |

| Menstruation | ||||||

| Postmenopausal | 2 (1487) | 1.193 (0.985–1.443)† | 0.0 | 0.526 | 1.81 | .070 |

| Premenopausal | 3 (682) | 1.715 (1.231–2.390)† | 0.0 | 0.369 | 3.19 | .001 |

A significantly high level of heterogeneity was noted in the included studies while employing a random effects model to assess the overall HR for OS (I2 = 83.3%, ph < 0.001) (Table 2). Therefore, subgroup analyses were further carried out for investigating plausible sources of heterogeneity among reports by the I2 index and Q statistic. Low or moderate heterogeneity was observed when patients were divided into multiple subgroups based on adjuvant endocrine treatment, TNM stage, sample size, type of study, and research region. In particular, heterogeneity was low in the subgroup analyses of adjuvant endocrine treatment (tamoxifen, I2 = 0.0%, ph = 0.537; without tamoxifen, I2 = 0.0%, ph = 0.413) and type of study (retrospective study, I2 = 0.0%, ph = 0.758). These results implied that the observed heterogeneity might have been caused by the multiple covariate effect. Of note, subgroup analyses based on these factors showed no marked alteration on the prognostic value of AIB1.

3.3. Associations of AIB1 expression with clinical indexes in BC

The associations of AIB1 expression with clinicopathological features are summarized in Table 4. Overexpression of AIB1 showed significant associations with HER2 positivity (pooled OR = 0.331, 95% CI 0.245–0.448, P < .001), poorly differentiated histological grade (pooled OR = 0.377, 95% CI 0.317–0.448, P < .001), high Ki67 (pooled OR = 0.501, 95% CI 0.410–0.612, P < .001), presence of lymph node metastases (pooled OR = 0.866, 95% CI 0.752–0.997, P = .045), and PR negativity (pooled OR = 1.447, 95% CI 1.190–1.759, P < .001). However, no significant association with ER status (pooled OR = 0.803, 95% CI 0.516–1.247, P = .328) or tumor size (pooled OR = 0.996, 95% CI 0.756–1.313, P = .977) was noted.

Table 4.

Meta-analyses of AIB1 overexpression classified by clinicopathological parameters.

| Study covariates | Studies (patients) | OR (95% CI) | I2 (%) | ph | Z | P | Model |

| ER status (positive/negative) | 6 (4164/1210) | 0.803 (0.516–1.247) | 89.1 | <0.001 | 0.98 | .328 | Random |

| Her2 status (negative/positive) | 4 (1822/229) | 0.331 (0.245–0.448) | 0.0 | 0.464 | 7.19 | <.001 | Fixed |

| Histological grade (well+ moderately differentiated/poorly differentiated) | 5 (1832/893) | 0.377 (0.317–0.448) | 0.0 | 0.429 | 11.09 | <.001 | Fixed |

| Ki67 (low/high) | 4 (1008/786) | 0.501 (0.410–0.612) | 0.0 | 0.409 | 6.77 | <.001 | Fixed |

| Lymph node metastasis (absence/presence) | 5 (1596/2136) | 0.866 (0.752–0.997) | 33.0 | 0.202 | 2.00 | .045 | Fixed |

| PR status (negative/ positive) | 3 (1293/987) | 1.447 (1.190–1.759) | 49.3 | 0.139 | 3.71 | <.001 | Fixed |

| Tumor size (≤2/ > 2cm) | 6 (1745/2491) | 0.996 (0.756–1.313) | 63.9 | 0.017 | 0.03 | .977 | Random |

3.4. Meta-regression and sensitivity analyses of AIB1 expression and OS in breast cancer

To further assess the plausible source of heterogeneity among articles, meta-regression analysis was performed. Although some factors found in the subgroup analysis might have been the cause of heterogeneity, regression analyses based on adjuvant endocrine treatment (P = .982), TNM stage (P = .722), sample size (P = .201), type of study (P = .060), research region (P = .140), and analysis method (P = .231) ultimately failed to identify the dominant factor responsible for the observed OS heterogeneity.

Next, sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the effect of each study on the pooled HR. The results revealed that all point estimates after omission of individual datasets were within the 95% CIs, indicating that no single article significantly affected the overall findings of the meta-analysis (Fig. 3). Furthermore, Begg (P = .721) and Egger (P = .353, Supplementary figure S1) tests showed no statistically significant publication bias. Thus, we considered the results of this analysis to be reliable and stable.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding each study in turn and recalculating the combined risk estimates for overall survival.

4. Discussion

There is mounting evidence that patients benefit from remarkable advances in breast cancer-related treatments, adjuvant therapies, and prognostic markers.[18] However, the mechanisms involved in BC remain complex and obscure. Thus, multiple studies are still trying to identify important factors involved in the occurrence and development of BC; in particular, recent data have identified genes and proteins specifically upregulated or downregulated in BC tissues that could be considered early diagnostic markers, prognostic markers, and/or therapeutic targets.[19,20] Therefore, we performed the current meta-analysis to determine valuable markers using online data. To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis assessing the association of AIB1 expression with OS in BC.

AIB1 was first identified in human BC cells, and an approximately 60% overexpression of this protein has been detected in all breast cancers.[4] AIB1 was originally considered an ER coactivator, but later suggested to exert biological effects through multiple pathways. On the one hand, AIB1 mediates estrogen's effects on ER-related gene expression and regulates the transcriptional activities of nuclear receptors, thereby influencing the growth of hormone-dependent BC.[21,22] On the other hand, it is widely admitted that AIB1 exerts its oncogenic activities through hormone-independent pathways. Specifically, certain hormone-independent pathways are involved in the carcinogenic effect of AIB1, for example, E2F1, IGF-I, and EGF pathways, which play critical roles in BC formation and progression.[23,24] Furthermore, AIB1 overexpression correlates with elevated p53 protein amounts as well as increased cellular proliferation, even when BC cells express a nuclear receptor antagonist,[23,25] and previous studies have demonstrated that AIB1 has an important function in BC tumorigenesis and metastasis by controlling cell malignancy.[26] Surprisingly, abnormal manifestations in cancers, such as overexpression of the atypical protein kinase C[27] and loss of heterozygosity at the speckle-type POZ protein locus,[28] could further stabilize aberrantly elevated AIB1 or regulate AIB1 activation. In addition, it is worth noting that AIB1 could significantly affect BC resistance to anti-estrogen therapeutics, especially tamoxifen.[29] Although the mechanism of tamoxifen resistance is complicated, the agonistic features of tamoxifen in BC cells could be enhanced by overexpression of AIB1 according to recent study.[30] Indeed, AIB1's roles in malignancy are well established, but its prognostic value in clinical BC cohorts remains ambiguous. Multiple convincing studies have reported that AIB1 overexpression is associated with unfavorable clinicopathological factors, and leads to poor prognosis.[13–17] Meanwhile, other findings suggest that AIB1 negatively regulates tumor suppressor genes and does not affect prognosis in BC.[8–11] Thus, the clinical relevance of AIB1 needs to be verified.

The present results based on 11 datasets comprising 6774 patients showed that AIB1 protein expression conferred reduced OS among all patients with BC. Hence, AIB1 overexpression could independently predict prognosis in BC; this finding confirms the carcinogenic effect of AIB1 in BC. Such relationships were confirmed in the subgroup analysis according to the analysis method, which showed that AIB1 maintained its prognostic relevance in BC patients irrespective of whether adjustment factors were removed. An additional remarkable finding of this meta-analysis was the prognostic value of AIB1 positivity only in women administered rational adjuvant therapy, suggesting that standard adjuvant therapy may require new and better clinical markers. At the same time, our study also found that AIB1 could maintain the stability of its results in different tumor stages, sample size, research methods, and research regions. Thus, these results could be applied in clinical practice and serve as a reference for improving patients’ beliefs and medication compliance. Moreover, despite the robustness of the pooled results, substantial heterogeneity was indeed found by the Cochrane's Q-statistic and I2 index tests. Therefore, stratified analyses were performed, and heterogeneity was considerably decreased in most subgroup analyses based on adjuvant endocrine treatment, TNM stage, sample size, type of study, and research region. However, in the meta-regression analysis, we ultimately failed to identify a dominant factor responsible for the observed OS heterogeneity. Consequently, a random effects model was required for subsequent investigation to rule out heterogeneity. Interestingly, in subgroup analysis, heterogeneity was greatly reduced without substantially changing the overall outcomes.

In addition, because of the associations of AIB1 with ER and tamoxifen resistance, the prognostic value of AIB1 positivity was evaluated in specified BC subgroups based on available clinical characteristics. Our results indicated that AIB1 positivity strongly reflected the prognosis of patients with ER-positive BC and premenopausal patients among the BC cohorts, whereas no such effects were observed in the corresponding subtypes. Previous evidence suggests that AIB1 modulates cancer development through hormone-dependent and hormone-independent signaling pathways.[21–24] Nevertheless, this study suggested that hormone-dependent mechanisms might be dominant. In addition, it must be noted that AIB1 involvement in tamoxifen resistance was reconfirmed, no association of AIB1 expression with clinical outcome was found in ER-positive patients administered tamoxifen in the analysis included 4 studies assessing 1797 patients; however, the prognostic value of AIB1 in BC was significantly found in ER-positive group and tamoxifen administration group. This indicates resistance to tamoxifen could result from AIB1's interaction with ER, and also reveals that the prognostic value of AIB1 in patients with BC might interact with ER status and tamoxifen regimen.

We also assessed the associations of AIB1 with clinicopathological factors, with the clinical meta-analysis revealing that AIB1 was associated with HER2 positivity, poorly differentiated histological grade, high Ki67, presence of lymph node metastases, and PR negativity, corroborating previously published results. However, regarding the correlation of AIB1 with ER, the obtained results were unexpectedly nonsignificant. A possible explanation is that AIB1's association with ER in many studies was based on ER gene expression, while the gene and protein expression levels of AIB1 are not consistent in BC.[4] Furthermore, ER expression is associated with multiple parameters, including patient age, lower tumor grade and proliferation, loss of p53, PR expression, and the activation of membrane receptor tyrosine kinases. Secondly, the associations of AIB1 with nuclear receptors were complex and closely related to the definition of positivity for nuclear receptors and proteins. As described in Table 1, different cutoffs for AIB1 were employed in various articles included in the current meta-analysis. However, we did demonstrate that AIB1 positivity was associated with an aggressive phenotype, thereby reflecting poor prognosis in BC.

Uncontrolled endocrine resistance and tumor growth and metastasis represent the major causes of BC-related death.[31] Fortunately, effective targeted therapy could substantially ameliorate the quality of life and survival of BC cases. In the past few years, several studies have revealed that AIB1 suppression notably reduces BC incidence and decreases the expression levels of IGF-I and insulin receptor substrate proteins in animal models; in addition, AIB1 knockdown was shown to restore cell sensitivity to tamoxifen in tamoxifen-resistant BC cell lines.[32] The remarkable prognostic value of AIB1 in BC patients was confirmed in this meta-analysis. Thus, AIB1 might be a crucial therapeutic target applicable to BC.

5. Limitations

This analysis had some limitations. First, only few studies were included, and substantial heterogeneity was noted between them. Secondly, operative methods and detailed adjuvant therapies differed in various studies, which could result in skewed analysis. Thirdly, different cutoffs for AIB1 were used in the included studies, reducing the accuracy and applicability of the obtained findings across diverse populations. Fourthly, many clinicopathological factors related to AIB1 were not explored because of the small number of articles assessed. Finally, although AIB1's function in BC was satisfactorily demonstrated, the mechanisms underlying AIB1-associated endocrine resistance and carcinogenesis remain unclear.

6. Future directions

Thus, prospective, randomized, larger-scale trials in various ethnic groups, along with homogeneous treatment approaches and scientific clinical annotation, are required for further investigating the clinical value of AIB1 in BC patients.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study first meta-analyzed AIB1's role in BC. AIB1 overexpression is related to HER2 positivity, poorly differentiated histological grade, high Ki67, presence of lymph node metastases, PR negativity, and poor survival in BC. Moreover, our results also indicate that AIB1 might play an indispensable role in tamoxifen resistance. These results suggest that AIB1 may be a new prognostic biomarker and a therapeutic target in BC, thus providing guidance for a long-term therapeutic strategy. However, in-depth study is warranted.

Author contributions

JH and JL conceived and designed the study. JH, JL, and MY collected the data. JL, MY, CM, and JL carried out the meta-analysis, systematic review, and manuscript drafting. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conceptualization: Jianjing Hou, Jianhua Liao.

Data curation: Jianjing Hou, Jingting Liu.

Formal analysis: Jingting Liu, Mengci Yuan.

Investigation: Jingting Liu, Mengci Yuan, Chunyan Meng.

Methodology: Jingting Liu, Chunyan Meng.

Software: Mengci Yuan, Chunyan Meng.

Validation: Mengci Yuan, Jianhua Liao.

Writing – original draft: Jianhua Liao.

Writing – review & editing: Jianjing Hou.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AIB1 = amplified in breast cancer 1, AR = androgen receptor, BC = breast cancer, CI = confidence interval, ER = estrogen receptor, HR = hazard ratio, OR = odds ratio, OS = overall survival, PR = progesterone receptor.

How to cite this article: Hou J, Liu J, Yuan M, Meng C, Liao J. The role of amplified in breast cancer 1 in breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Medicine. 2020;99:46(e23248).

JH and JL contributed equally to this work.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are publicly available.

HR = hazard ratio, OS = overall survival. Quality was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale.

Protein expression was evaluated by using semiquantitative weighted histoscore method.

The score for intensity was added by the score for extent of staining.

The score was based on the technology of automated quantitative analysis; NS data were not shown.

OS = overall survival, HR = hazard ratio, CI = confidence interval, ph = p value for heterogeneity based on Q test, P = P value for statistical significance based on Z test.

Pooled HRs were derived from random-effect model.

Pooled HRs were derived from fixed-effect model.

CI = confidence interval, ER = estrogen receptor, HR = hazard ratio, OS = overall survival, P = P value for statistical significance based on Z test, ph = p value for heterogeneity based on Q test, PR = progesterone receptor.

Pooled HRs were derived from random-effect model.

Pooled HRs were derived from fixed-effect model.

CI = confidence intervals, ER = estrogen receptor, OR = odds ratio, P = P value for statistical significance based on Z test, ph = p value for heterogeneity based on Q test, PR = progesterone receptor.

References

- [1].Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Yuan M, Liao J, Luo J, et al. Significance of Vesicle-associated membrane protein 8 expression in predicting survival in breast cancer. J Breast Cancer 2018;21:399–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Dihge L, Bendahl PO, Grabau D, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and the estrogen receptor modulator amplified in breast cancer (AIB1) for predicting clinical outcome after adjuvant tamoxifen in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008;109:255–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Guan XY, Xu J, Anzick SL, et al. Hybrid selection of transcribed sequences from microdissected DNA: isolation of genes within amplified region at 20q11-q13.2 in breast cancer. Can Res 1996;56:3446–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tilghman SL, Sabnis G, Brodie AM. Upregulation of AIB1, aromatase and ERalpha provides long-term estrogen-deprived human breast cancer cells with a mechanistic growth advantage for survival. Hormone Mol Biol Clin Investigation 2011;3:357–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Anzick SL, Kononen J, Walker RL, et al. AIB1, a steroid receptor coactivator amplified in breast and ovarian cancer. Science 1997;277:965–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Myers E, Hill AD, Kelly G, et al. Associations and interactions between Ets-1 and Ets-2 and coregulatory proteins, SRC-1, AIB1, and NCoR in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2005;11:2111–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kirkegaard T, McGlynn LM, Campbell FM, et al. Amplified in breast cancer 1 in human epidermal growth factor receptor-positive tumors of tamoxifen-treated breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Rese 2007;13:1405–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yamashita H, Nishio M, Toyama T, et al. Low phosphorylation of estrogen receptor alpha (ERalpha) serine 118 and high phosphorylation of ERalpha serine 167 improve survival in ER-positive breast cancer. Endocrine Related Cancer 2008;15:755–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Alkner S, Bendahl P, Grabau D, et al. The role of AIB1 and PAX2 in primary breast cancer: validation of AIB1 as a negative prognostic factor. Ann Oncol 2013;24:1244–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Alkner S, Jensen MB, Rasmussen BB, et al. Prognostic and predictive importance of the estrogen receptor coactivator AIB1 in a randomized trial comparing adjuvant letrozole and tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal breast cancer: the Danish cohort of BIG 1-98. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017;166:481–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med 1998;17:2815–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Alkner S, Bendahl PO, Grabau D, et al. AIB1 is a predictive factor for tamoxifen response in premenopausal women. Ann Oncol 2010;21:238–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Spears M, Oesterreich S, Migliaccio I, et al. The p160 ER co-regulators predict outcome in ER negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;131:463–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Harigopal M, Heymann J, Ghosh S, et al. Estrogen receptor co-activator (AIB1) protein expression by automated quantitative analysis (AQUA) in a breast cancer tissue microarray and association with patient outcome. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;115:77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Narbe U, Sjostrom M, Forsare C, et al. The estrogen receptor coactivator AIB1 is a new putative prognostic biomarker in ER-positive/HER2-negative invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2019;175:305–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Burandt E, Jens G, Holst F, et al. Prognostic relevance of AIB1 (NCoA3) amplification and overexpression in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013;137:745–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Montero AJ. Guidelines are essential to improving clinical outcomes in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treatment 2015;153:1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Saito Y, Li L, Coyaud E, et al. LLGL2 rescues nutrient stress by promoting leucine uptake in ER(+) breast cancer. Nature 2019;569:275–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kosvyra A, Maramis C, Chouvarda I. Developing an integrated genomic profile for cancer patients with the use of NGS data. Emerging Sci J 2019;3:157–67. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hudelist G, Czerwenka K, Kubista E, et al. Expression of sex steroid receptors and their co-factors in normal and malignant breast tissue: AIB1 is a carcinoma-specific co-activator. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2003;78:193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Barkhem T, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Molecular mechanisms, physiological consequences and pharmacological implications of estrogen receptor action. Am J Pharmacogenomics 2004;4:19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Louie MC, Zou JX, Rabinovich A, et al. ACTR/AIB1 functions as an E2F1 coactivator to promote breast cancer cell proliferation and antiestrogen resistance. Mol Cell Biol 2004;24:5157–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ma G, Ren Y, Wang K, et al. SRC-3 has a role in cancer other than as a nuclear receptor coactivator. Int J Biol Sci 2011;7:664–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bouras T, Southey MC, Venter DJ. Overexpression of the steroid receptor coactivator AIB1 in breast cancer correlates with the absence of estrogen and progesterone receptors and positivity for p53 and HER2/neu. Cancer Res 2001;61:903–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Long W, Yi P, Amazit L, et al. SRC-3Delta4 mediates the interaction of EGFR with FAK to promote cell migration. Mol Cell 2010;37:321–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Yi P, Feng Q, Amazit L, et al. Atypical protein kinase C regulates dual pathways for degradation of the oncogenic coactivator SRC-3/AIB1. Molecular cell 2008;29:465–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Li C, Ao J, Fu J, et al. Tumor-suppressor role for the SPOP ubiquitin ligase in signal-dependent proteolysis of the oncogenic co-activator SRC-3/AIB1. Oncogene 2011;30:4350–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Osborne CK, Bardou V, Hopp TA, et al. Role of the estrogen receptor coactivator AIB1 (SRC-3) and HER-2/neu in tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003;95:353–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Reiter R, Oh AS, Wellstein A, et al. Impact of the nuclear receptor coactivator AIB1 isoform AIB1-Delta3 on estrogenic ligands with different intrinsic activity. Oncogene 2004;23:403–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Habibeh Z. Effects of salvia officinalis extract on the breast cancer cell line. Sci Med J 2019;1:25–9. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Su Q, Hu S, Gao H, et al. Role of AIB1 for tamoxifen resistance in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells. Oncology 2008;75:159–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.