Abstract

There has been a substantial rise in the number of women pursuing careers in neurology. However, research has shown that women in neurology have high rates of burnout with gender disparities in burnout and attrition in the field. Recently, there was a call from the NIH, including the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, asking for input on factors that may limit or discourage grant applications from women. As the recipients of the highly coveted NIH career mentored awards (K awards) in headache medicine, we applaud the NIH for asking for gender-specific feedback and for raising awareness of research showing that female faculty on the Research Track are at an increased risk of departure. Using the NIH model for the Responsible Conduct of Research and the tenant of Nurturing the Fertile Environment, we discuss specific challenges in academic research that may contribute to gender differences in neurology research success. Although the rate of women conducting NIH-funded migraine research increased from 23% to 41% over the last 10 years, more women are currently in training compared with independence, with 6/6 of the NIH training grants but only 12/36 of the NIH research-level grants, held by women in fiscal years 2017–2019. We suggest concrete solutions to these challenges to ensure the success of women in research reaching independence.

Academic medicine, including neurology, has historically been dominated by men. However, this is changing. More women than men applied to US medical schools in 2018, and women have comprised the majority of matriculants to medical schools since 2017.1 Although only 25% of active neurologists were women in 2010, this increased to 29.4% by 2017, and 45% of neurology trainees in 2017 were women.2

As more women enter academic medical careers in neurology, professional organizations and the NIH have made concerted efforts to support their career development. For example, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and American Headache Society host annual Women in Leadership seminars at their national conferences. In 2017, the AAN also initiated a formal year-long Women Leading in Neurology program. The American Neurological Association has also held professional development courses such as Recruitment and Retention of Women in Academic Neurology.3 The NIH, including the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), recently issued a call requesting input from the scientific community to identify factors that may limit or discourage grant applications from women.4 The NIH also asked for suggestions on strategies to increase the number of applications by women to the High Risk, High Reward research program.

As the recipients of NIH mentored career awards (K awards) in headache medicine, we aim to discuss challenges that may contribute to gender disparities in academic research success and offer potential solutions. To provide a framework for our response, we used the NIH's model for the Responsible Conduct of Research. The 3 pillars of the NIH Model of Responsible Conduct of Research are Nurturing Fertile Environment, Foundation of Research Integrity, and Robust Research Training.5 In this article, we seek to describe the greatest challenges for women in the Responsible Conduct of Research with a particular focus on Nurturing Fertile Environment. However, the other pillars Robust Research Training and Foundation of Research Integrity are clearly affected by the environment and are discussed as well.

Disparity of women in the neurology research pipeline has created a challenge to Nurturing a Fertile Environment

The challenges facing women in academic medicine within neurology and other fields are significant and permeate all levels of training, with available research suggesting that this begins as early as the undergraduate level. An examination of student-faculty interactions in undergraduate research laboratories demonstrated that women interacted less frequently with their faculty mentors than men.6 In a qualitative study assessing the experience of undergraduates during summer research programs at 9 universities, women undergraduates expressed more discomfort in informal social interactions with their mentors than men.7 Although more research in this area is needed, we argue that the ability for men to more easily engage in micro-social interactions with research mentors at the undergraduate level may give an early advantage to men as students make early decisions about whether to enter the research pipeline.

Undergraduate faculty may also have biases that limit early exposure to research training for women. Available data indicate that faculty of both genders find undergraduate women to be less competent and less worthy of being hired for laboratory manager positions than men with identical application materials.8 Furthermore, undergraduate women who are in laboratory manager positions are likely to be offered lower starting salaries and receive less career mentoring than men.8 These findings indicate that women may not have an equal opportunity to enter the research pipeline during undergraduate training due to implicit biases held by faculty of both genders that favor men. We argue that research is needed to address potential gender disparities at these key early time points and settings (e.g., high school science and math classrooms, undergraduate departments, and postbaccalaureate programs).

Gender disparities in attrition among neurology faculty in academic medicine

Despite trends indicating that more women are entering neurology, men continue to dominate academic neurology departments, and this disparity increases up the ranks in seniority/leadership. In 2016, less than one-third (31.5%) of AAN members were women.9 In 2018, 40% of 6,086 academic positions in neurology departments were held by women, but women held only 12.6% of the tenured positions (professors and associate professors), and only 14 of 113 (12%) department chairs were women.10 There are likely multiple factors contributing to the lack of women in senior leadership roles within neurology departments.

The high rate of attrition among women conducting research in academic medical centers is of utmost concern. A report published over 10 years ago in 2008 by the Association of American Medical Colleges11 revealed that the 10-year attrition rate was 38% for all faculty and 43% for first-time assistant professors with an increased risk of departure within the Research Track compared with the Clinician-Educator Track.12 These rates have consistently been higher for women compared with men as far back as 1981.11

Faculty on the Research Track were at an increased risk of departure compared with those on the tenure and those on the Clinician-Educator tracks.12 These high rates of attrition have implications for the educational mission of academic medical centers,13 the quality of research and level of research productivity,14 and the ability to find women mentors in the field.

A recent survey of medical school faculty identified several predictors of serious intent to leave academic medicine across genders, including difficulties balancing work and family life, the inability to comment on performance of institutional leaders, absence of faculty development programs, absence of an academic community, and failure of chairs to regularly evaluate academic progress.13 A population-based survey conducted by the AAN revealed that women neurologists held more negative views than men toward their overall workload, work-life balance, departmental leadership, and professionalism within the department.15 Furthermore, only women reported dissatisfaction with the erosion of academic productivity due to departmental demands to meet clinical billing benchmarks. Why women neurologists are more susceptible to these risk factors for early departure from academic medical careers than men is uncertain. However, it is clear that contrary to popular belief and similar to high-achieving women in other professions, women neurologists leave their careers for a variety of reasons, not just to care for their families.16

To prevent gender disparities in faculty attrition, we argue that leaders in neurology departments should consider implementing strategic planning processes that will provide all Research Track faculty with the support, protected time, and resources needed to reach academic career milestones (e.g., internal small grant awards, bridge funding, and formal interdepartmental research mentorship programs). Departmental review processes can be implemented to ensure equity in distribution of such resources across faculty members. The authors of one study proposed an alternative solution: “A reduction in duties, including a part-time option for up to 6 years for illness, personal or family, and an optional extension of the probationary period before mandatory review for academic advancement.”17 However, measures that aim to reduce work duties or delay promotion may have long-term consequences for career advancement and could further contribute to gender disparities in leadership roles if women take advantage of such provisions more frequently than men.15

Gender disparities in pay

In academia generally, women earn a mean of $20,520 annually less than men, and this disparity has not changed for over 17 years.18 Regarding physician-scientists specifically, women earn $12,000–$33,000 annually less than men. This means that men in academic medicine will earn at least $350,000 more than women over the same 30-year career (and this does not include the compound interest on the invested extra income).19 This is a particularly vexing issue within the field of neurology where the gender pay gap is known to be greater than most other medical specialties20 Research on whether this gender pay gap affects the decision of women in neurology to enter and/or depart early from academic medical careers is needed.

Gender disparities affect the foundation of research integrity

We argue that a research environment that disproportionately disadvantages women weakens the foundation of research integrity. Here, we discuss how this concept applies to gender disparities in research funding, collaboration and publications, results reporting and dissemination of findings, delayed childbearing, and availability of women mentors and leaders within neurology.

Research funding

Funding is associated with both data quality and professional advancement. Men applying for early career awards reportedly receive greater start-up packages (median $936,000) than women (median $348,000).21 Research is needed to understand why this disparity exists. On the one hand, women and men may choose to pursue research topics that require differential startup packages (e.g., basic vs clinical sciences). However, the issue is likely more complex. For example, implicit gender biases of department chairs against women in salary negotiations have been well documented.22 There are also data suggesting that women are less effective at salary negotiations than men.23 In a recent study of 427 surgery residents, women and men reported similar career goals, but women had lower expectations for their minimum starting salary, did not believe that they had the tools to negotiate effectively, and were less likely to pursue multiple job offers to negotiate a higher salary.24 Inadequate mentoring of young women in negotiation skills and lack of training for department chairs and other leaders about the gender biases that may affect their salary decisions are important factors that require further study.

Although there are equal numbers of men and women applying for mentored clinical science grants (K23 awards), it is estimated that close to half of the women eligible to pursue basic research topics (K08 awards) do not apply. Historically, although funding rates for K23 awards are about the same across gender, there was a gender disparity in the success rate of first-time R01 applicants (20% for women and 24% for men, p = 0.006).25 There was also a gender disparity in the success rate of experienced applicants (32% for women and 36% for men, p = 0.0004).25 Recent research shows evidence of a gender disparity in the size of first-time grants, with women receiving a median of $126,615 vs $165,721 for men in annual direct costs across the Big Ten Universities, the 8 Ivy League Universities, and the top 50 NIH most funded institutions.26

There are several potential mechanisms underlying this gender disparity in funding. Several studies have found that women and minorities are more likely than men to submit NIH applications focused on historically underfunded topics, which likely contributes to the funding disparity and places women with multiple minority status at a particular disadvantage.27,28 This issue is interesting to consider in light of the current preponderance of women holding active K23 awards in headache, a disease with high public health impact that has historically been underfunded by NIH.29 Furthermore, although women are less likely to enter science careers and receive initial R-level funding, once they do receive R-level funding, it is important to recognize that they are just as likely as men to maintain continuous funding over the lifespan of their research career.30

Based on these findings, we argue that leaders in the NIH need to pay special attention to gender disparities affecting funding success at the earliest career stages (e.g., F awards, K awards, and initial R01 awards), especially for individuals with multiple minority status (e.g., women from racial or ethnic minority groups) and within topic areas that have been underfunded relative to the burden of disease (e.g., headache).

Collaborations and publications

Women are less likely to participate in collaborations that lead to publication31 and are much less likely to be listed as either first or last author on an article.32 In 2015, a study of high-profile neurology journals found that only 25% of peer-reviewed articles had a woman as a first author, and only 18% had a woman as a senior author.33 The reasons for gender disparities in publication are poorly understood. Some hypotheses for the gender disparities in publication are women have less funding for independent research,34 women contribute less to manuscript preparation,31 men successfully negotiate for better positions in the authorship order,35 and/or there is a bias against women in the review process.32 There may be a vicious cycle that creates a systemic disadvantage for women in academia due to cumulative impacts of limited research funding, underrepresentation of women on editorial boards, and lack of peer-reviewed publications in high-impact journals, which then leads to even less funding, and the cycle continues.34 Because of this vicious cycle, the contributions of women neurologists in academic medicine may be perpetually marginalized while the male-dominated scientific perspective continues relatively unchecked.36

Benevolent sexism may also play a role, where men and women unconsciously limit publication or collaborative opportunities for women colleagues in an effort to help or protect them from additional duties. For example, colleagues or collaborators may not want to burden women with additional challenges of manuscript writing or grant preparation if they are aware of a woman's full life responsibilities. Although benevolent sexism is an unconscious bias that may be rooted in a good intention (i.e., desire to protect or help), this bias can unintentionally result in reduced agency for women and lost academic opportunities. Additional research is needed to determine whether women or men are more likely to engage in benevolent sexism to protect their women colleagues. Increasing awareness of benevolent sexism for both genders is critical to addressing the inherent barriers that arise from such biases.

Results reporting and dissemination of research findings

Gender differences in results reporting can also affect research integrity. For example, in a study analyzing the abstracts from 6.2 million articles indexed in PubMed over a 15-year period, articles in which the first and last author were both women were less likely to use positive terms to depict the studies' findings compared with studies in which the first and/or last author was a man.37 This was particularly apparent in the high-impact journals. Importantly, positive presentation of the findings was associated with more downstream citations.

Women also have fewer opportunities to present their research to professional audiences. For example, men in academia give over twice as many colloquia (69%, n = 2,519) compared with women (31%, n = 1,133), although acceptance rates for invitations extended to men and women are equal.38,39 Women have also published fewer invited commentaries in medical journals and have received fewer AAN recognition awards for contributions to research.40,41

Reasons and consequences for gender disparities in results reporting and dissemination of findings are likely multifactorial. For example, differential approaches to spin on research findings between men and women may influence acceptance of manuscripts in peer-reviewed journals as well as professional speaking invitations.42 Implicit gender biases of departmental/conference/journal leadership may also play a role.

Delayed childbearing

Many women in academic research delay childbearing in favor of pursuing their careers, which may have long-term impacts on physical and emotional well-being. For example, 25% of women physicians experience infertility, much higher than the US average of 9%–18%,43 and women who pursue careers in research may have an even higher likelihood of delayed childbirth with resulting infertility.44 This can result in multiple stressors that may differentially affect women compared with men (e.g., limited finances, lack of scheduling flexibility, and societal stigma against fertility treatment). Because of the delay in childbirth, challenges arise in raising young children and caring for elderly family members at key times for a productive research career. See table 1 for specific examples and recommendations for how these issues specifically affect women in academic research and ways in which they may be individually and systematically addressed.

Table 1.

Scenarios that demonstrate challenges that disproportionately affect women researchers and potential individual and systematic ways to overcome this challenge

Access to women mentors and leaders

A recent systematic review of mentorship of women in academic medicine found that the focus of mentorship is generally geared toward junior faculty and medical trainees and that there typically are not mentorship programs available for mid-career or senior faculty.45 When surveying women faculty at a large academic medical center, about half (46%) reported that they did not have a mentor, and many felt that their mentorship needs were not met.46

We recognize that successful mentorship is not necessarily gender specific, and we are not advocating for all mentor-mentee relationships to be matched on gender. However, successful mentorship is more likely for mentees who have several mentors (vs a single mentor) from different backgrounds to meet a variety of mentorship needs. In our collective experience as women with early research careers, we have found that having a woman mentor with similar life experiences beyond the laboratory to be particularly beneficial to supporting our career success.

We would also like to highlight that the NIH has a funding mechanism that provides protected time for mid-career faculty to mentor early career scientists (K24 award). Currently, the active K24 awards in neurology research sponsored by the NINDS are all held by men.47 Critically, the NINDS no longer has an open program announcement for K24 awards and does not have alternative mechanisms available to support mid-career faculty in mentoring junior scientists.48 If the NINDS does not address this crucial gap in funding policy, it is unlikely that the investments made in their currently funded K awardees will translate to subsequent mentorship and training for the next generation of neurology researchers. The lack of senior women in positions of leadership and in academic research not only leaves a dearth of mentors available to help guide mentees on their career paths but also creates a gap in sponsorship for women,49 which may have an even more significant negative gender impact. Sponsors differ from mentors in that they come from positions of power and advocate publicly for their proteges, spotlighting them with resulting enhanced credibility and recognition.

Current state in neurology and in NIH-funded migraine research

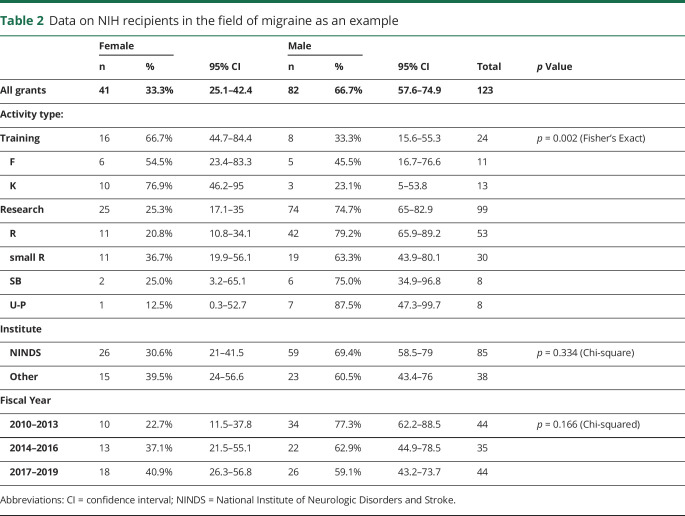

To better quantify the extent to which women are actively participating in academic research and applying for and receiving NIH-funded research, we identified currently funded NIH awards within a specific neurology field, headache medicine, to compare grant type by gender over the past 10 years. Specifically, on January 10, 2020, we searched NIH RePORTER (projectreporter.nih.gov/reporter.cfm?frs=1&icde=48240977) for all new extramural grants awarded from 2010 to 2019 where the term migraine was included in the project title or abstract. This yielded 183 projects. Project titles and, where relevant, abstracts were reviewed, and projects that were not directly focused on migraine or headache were excluded. For program grants with multiple programs that met criteria only the largest, overarching project was included and subprojects were excluded. This yielded a total of 123 projects. Projects were categorized by activity code into categories of (1) Training, which included Fellowship “F” and Career Development “K” awards, and (2) Research, which included “R-level,” Small Business “SB,” and Cooperative agreements/program grants “U-P.” Principal investigators were categorized as men vs women based on knowledge of the person (where applicable), publicly available photographs, or typical association with first/middle name. Analyses were then performed using STATA.

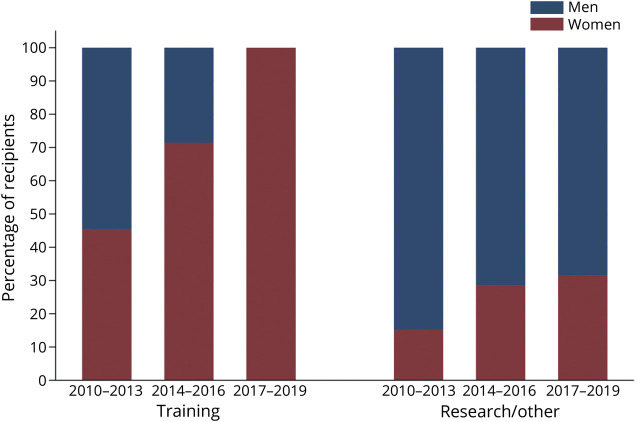

Our results revealed that the proportion of new grants awarded to women in migraine research nearly doubled over the past 10 years; women received 23% of these grants from 2010 to 2013, but 41% from 2017 to 2019 (table 2). This change was more dramatic for training grants (figure). All the current NIH-funded career development awards in the field of headache medicine are funding women, but only 32% of the current Research/Other grants are funding women. More time will be needed to see whether the current investments in the career development of women in migraine research will translate to successful transitions to independent research funding.

Table 2.

Data on NIH recipients in the field of migraine as an example

Figure. Percent of men vs women NIH recipients in the field of migraine.

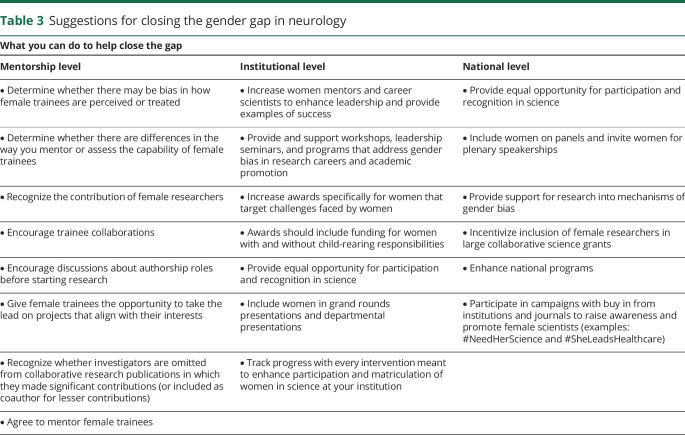

Proactive ways to address gender disparities in neurology research

From our direct experiences, we have created a table of some of the most significant challenges in the field and suggestions for how these challenges may be remedied at both an individual and systemic level (table 1). In writing this article, we found that our opinions and experiences were sometimes disparate, so there is no one-size-fits-all approach. Many of the challenges described in table 1 may also not be specific to women. Furthermore, there may be personality traits that lead to certain challenges to occur more often than women than in men but are not necessarily gender specific. For example, clinical researchers typically have difficulty setting boundaries around clinical care, and this may be even more challenging for women clinical researchers than men based on personality differences rather than gender.

Systematic grants and programs can also specifically target the challenges faced by women entering and staying in the research pipeline, particularly for those with multiple minority status. At the NIH, diversity supplements are available at most institutes to support the research and training of undergraduate students, fellows, and early career faculty from backgrounds that are underrepresented in science.50 Foundation grants are also available, such as the Doris Duke Fellowship to Retain Clinical Scientists, which provides “supplemental, flexible funds to early-career physician-scientists working on clinical research projects and facing extraprofessional demands of caregiving.”51 There are also mechanisms within academic medical centers that provide initial research training opportunities to undergraduate students from diverse backgrounds (e.g., the J. Steven Reznick Diversity and Psychological Research Grant at UNC-Chapel Hill and the Underrepresented Minorities in Research Internship at Seattle Children's Research Institute). These systematic programs can directly target the barriers that exist that can unequally affect women, although they are predominantly focused on supporting individuals at the earliest stages of research training. To slow the early departure of women from careers in academic neurology, we argue that the NIH, academic institutions, and individual neurology departments should consider developing mechanisms that support women and individuals with multiple minority status at later career stages where the risk of leaks in the research pipeline is greater.

Recently, the AAN developed a Gender Disparity Task Force, which provided recommendations to address gender disparities in academic neurology departments.9 These included improved transparency about neurology compensation at each career stage, providing formal training for male and female mentors to support successful mentorship of women trainees, increasing networking opportunities for women, highlighting women neurologists who have achieved leadership roles or professional success, alternative practice options to support work/life balance, and the creation of a fund to support relevant scholarship on the subject. This list represents excellent suggestions, and ensuring that these recommendations are enacted will be critical to the advancement of women in the field of neurology. We recommend that the AAN Gender Disparities Task Force partner with the AAN Diversity Task Force to identify and address the specific career development needs of neurologists who have multiple minority status because they are at a particular risk of early departure from the research pipeline.

One of the challenges many individuals face in medicine is travel required to attend national and international meetings, which is critical for career development and also directly conflicts with caretaking responsibilities for young children and elderly family members. To partially address this challenge, there are now a number of private Facebook groups specifically for women in academic medicine (e.g., Facebook Groups such as The Physicians Moms Group, Women Neurologists Group, and Migraine Mavens), and Twitter is increasingly used to promote and disseminate research findings.52 In recognition of the growing importance of social media efforts for career advancement, the Mayo Clinic's Academic Appointments and Promotions Committee has now integrated social media activities in the criteria for promotion.53 That being said, we are not advocating at this time for social media to entirely replace face-to-face opportunities for career development.

Importantly, institutional leadership can play a significant role in addressing gender disparities. The NIH studied whether the NIH Neuroscience Research Portfolios differ depending on whether the research enterprise is led by a man or a woman. Women-led research enterprises of medical schools had research portfolios that were 26% ± 11% education/mentoring, community-based research, and research facilities projects, whereas it was 4% ± 2% for research enterprises led by men (p < 0.03).54 Of interest, in institutions where the research dean changed and the transition was man to man, the NIH neuroscience research grant portfolio was unchanged. However, when the transition was man to woman, the NIH neuroscience portfolio included “more epidemiologic/community-based research and core facility training grants.”54 Thus, including women in senior research enterprise position(s) or at least doing individual institutional reviews of the NIH neuroscience portfolio might be important to ascertain whether topics and/or study designs perhaps done more frequently by women are included in the portfolio.54 The NIH has offered career development awards in the form of K awards that are important for the transition to independence.55 These programs (both institutional KL2 and K12 and more advanced K08, K23) can offer additional support to women that may be more vulnerable in the early career stage.56 However, there still lie gender gaps that exist beyond the K award that should be recognized. In a study of 589 male and female K awardees, although most awardees continued in academic medicine with significant time doing research, women were less likely to be promoted and were less likely to view themselves as successful.57 Furthermore, as a major benchmark of independence, women who receive K awards remain less likely to receive an R01 compared with their male counterparts.57,58

Over the past 30 years, the NIH has taken steps to target gender disparities in research across medical fields. For example, the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH) has a key goal to increase the representation of women in biomedical science careers. Through the ORWH, programs that support reentry into research and career development awards like Building Interdisciplinary Careers in Women's Health have increased opportunities for women. Although these opportunities are available for both men and women, women stand to benefit specifically. The ORWH has also participated in the NIH Working Group on Women in Biomedical Careers to address issues facing women trainees. This has led to partnerships with other NIH offices to double parental leave for trainees, the ESI extension, and other provisions like Keep the Thread to adjust work times around caregiving and Extend the Clock to adjust tenure timing around time burdens of family care.59 Furthermore, the NIH is demonstrating its priority for gender representation with the very awareness of the lack of diversity of grant submissions and request for information on why and how to increase gender representation in research.4

We argue that the NIH could further support women in academic medicine and women's health research as a field by allowing the ORWH to become a funding institute.

Limitations

A significant limitation of this article is that we have used a binary definition of gender identity (men vs women), which reflects the state of the published research in this area. Future studies should consider including nonbinary definitions of gender identity to examine how this may intersect with career development in academic medicine. Moreover, few studies have examined the additional barriers faced by members of multiple minority groups defined by sexual orientation (e.g., LGBTQ+), race, ethnicity, or religion, and identification of barriers and development of strategies to recruit, retain, and support these individuals require further attention that is beyond the scope of this review.17,60,61

Conclusions

In conclusion, there are many challenges to creating a fertile environment for women conducting research, affecting the responsible conduct of research in the field of neurology. We present the most salient barriers and propose a variety of solutions to improve the neurology research environment (tables 1 and 3). A powerful change with a direct impact on gender disparities in the funding of female researchers and Women's Health research would be the ability for the NIH ORWH to have independent funding opportunities specific to women and women's health. We also call on leaders at the NINDS to reissue the K24 career development mechanism or provide an alternative to allow mid-career investigators to dedicate their time and effort to mentorship and training of the next generation of neurology researchers.

Table 3.

Suggestions for closing the gender gap in neurology

National organizations have developed many career development leadership programs for women, which demonstrate the awareness of this topic. Research needs to investigate the effectiveness of these programs and evaluate additional opportunities that may provide additional support. The efforts already made by the NIH, the AAN, and other subspecialty organizations demonstrate the importance of this priority, and we hope for continued work toward addressing these barriers to support women pursuing and continuing in their careers related to researching neurologic disorders.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Ms. Sarah Corner for her help coordinating this effort. Her salary is supported by a grant to Dr. Minen from the Doris Duke Fellowship to Retain Clinical Scientists. The purpose of the grant is to provide supplemental, flexible funds to early-career physician-scientists working on clinical research projects and facing extraprofessional demands of caregiving.

Glossary

- AAN

American Academy of Neurology

- NINDS

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

- ORWH

Office of Research on Women's Health

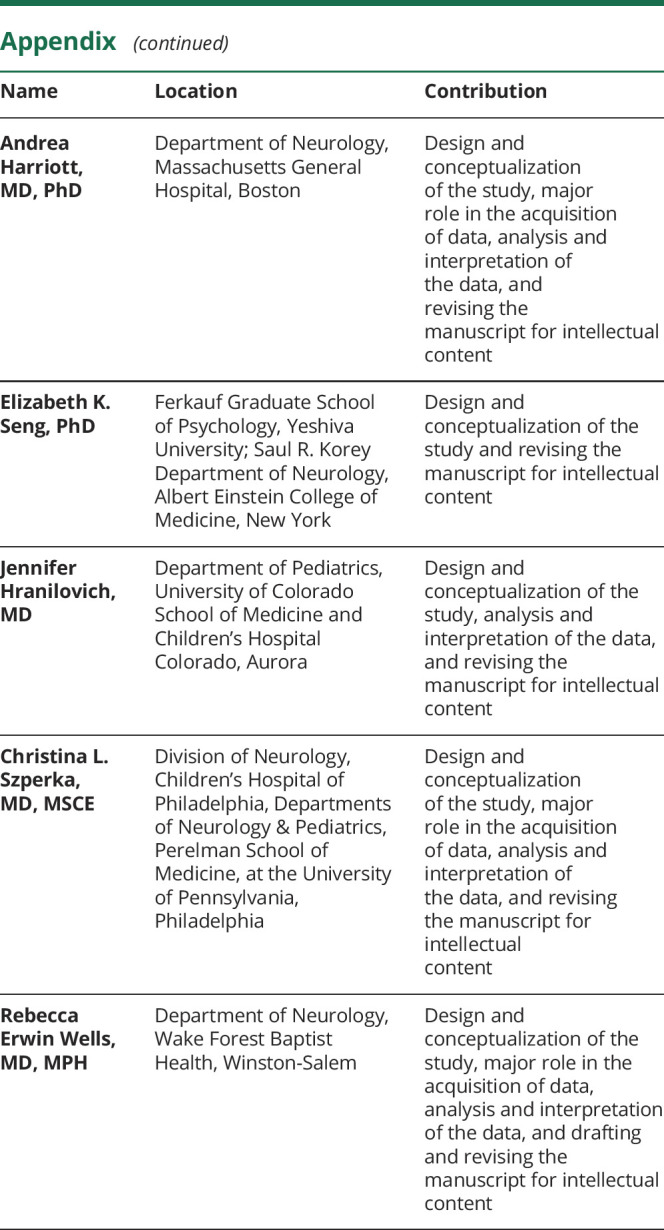

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

M.T. Minen receives salary support from the NIH NCCIH K 23 AT009706-01 and grant support for a Research Data Associate from the Doris Duke Fellowship to Retain Clinician Scientists. E.F. Law receives salary support from the NIH NINDS K23 NS089966-01A1. E.K. Seng receives salary support from the NIH NINDS K23 NS096107 05 and has funding from the NCATS (CTSA UL1TR002556-03; Seed Fund). C.L. Szperka receives salary support from the NIH NINDS K23NS102521. R.E. Wells received salary support from the NIH NCCIH K23 AT008406 05.

Discosure

M.T. Minen and E.F. Law report no disclosures. A. Harriott discloses research support from electroCore and served on the scientific advisory board of Bristol-Myers Squibb. E.K. Seng has consulted for GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, and Click Therapeutics. J. Hranilovich reports no disclosures. C.L. Szperka has received grant support from Pfizer, and her institution has received compensation for her consulting work for Allergan; she receives research funding from the FDA. R.E. Wells has no financial disclosures. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.AAMC. AAMC Applicant Matriculant Data File as of 11/26/2018. AAMC; 2018. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/system/files/d/1/92-applicant_and_matriculant_data_tables.pdf. Accessed March 14, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.AAMC. Active Physicians by Sex and Specialty: AAMC; 2017. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-sex-and-specialty-2017. Accessed March 14, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Neurological Association. Professional development courses. American Neurological Association Web site. Available at: myana.org/education/programs. Accessed January 13, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.NIH, Office of Strategic Coordination (Common Fund). Request for Information (RFI): Increasing the Diversity of Applications to the NIH Common Fund High-Risk, High-Reward Research Program. NOT-RM-20-002. 2019. Available at: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-RM-20-002.html. Accessed March 14, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Responsible Conduct of Research Training. 2016. National Institue of Health Office of Intramural Research Web site. Available at: oir.nih.gov/sourcebook/ethical-conduct/responsible-conduct-research-training. Accessed March 3, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aikens ML, Robertson MM, Sadselia S, et al. Race and gender differences in undergraduate research mentoring structures and research outcomes. CBE Life Sci Educ 2017;16:ar34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniels HA, Grineski SE, Collins TW, Frederick AH. Navigating social relationships with mentors and peers: comfort and belonging among men and women in STEM summer research programs. CBE Life Sci Educ 2019;18:ar17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moss-Racusin CA, Dovidio JF, Brescoll VL, Graham MJ, Handelsman J. Science faculty's subtle gender biases favor male students. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:16474–16479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Academy of Neurology, GDTF. Gender Disparity Task Force Report. AAN; 2017. Available at: https://www.aan.com/conferences-community/member-engagement/Learn-About-AAN-Committees/committee-and-task-force-documents/gender-disparity-task-force-report/. Accessed March 14, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.AAMC. Medical School Faculty by Sex, Rank, and Department, 2018. AAMC Faculty Roster; 2018. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/faculty-institutions/report/faculty-roster-us-medical-school-faculty. Accessed March 14, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander H, Lang J. The long-term retention and attrition of U.S. medical school faculty. AAMC Anal Brief 2008;8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Speck RM, Sammel MD, Troxel AB, et al. Factors impacting the departure rates of female and male junior medical school faculty: evidence from a longitudinal analysis. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:1059–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowenstein SR, Fernandez G, Crane LA. Medical school faculty discontent: prevalence and predictors of intent to leave academic careers. BMC Med Educ 2007;7:37–6920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Academy of Sciences (US), National Academy of Engineering (US), and Institute of Medicine (US). Beyond Bias and Barriers: Fulfilling the Potential of Women in Academic Science and Engineering. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LaFaver K, Miyasaki JM, Keran CM, et al. Age and sex differences in burnout, career satisfaction, and well-being in US neurologists. Neurology 2018;91:e1928–e1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone P. Opting Out': Challenging Stereotypes and Creating Real Options for Women in the Professions by Pamela Stone, Gender & Work: Challenging Conventional wisdom, harvard business school, 2013. Gender & Work: Challenging Conventional Wisdom. Harvard Business School; 2013:5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasan TF, Turnbull MT, Vatz KA, Robinson MT, Mauricio EA, Freeman WD. Burnout and attrition: expanding the gender gap in neurology? Neurology 2019;93:1002–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freund KM, Raj A, Kaplan SE, et al. Inequities in academic compensation by gender: a follow-up to the national faculty survey cohort study. Acad Med 2016;91:1068–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Stewart A, Sambuco D, DeCastro R, Ubel PA. Gender differences in the salaries of physician researchers. JAMA 2012;307:2410–2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silver JK. Understanding and addressing gender equity for women in neurology. Neurology 2019;93:538–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sege R, Nykiel-Bub L, Selk S. Sex differences in institutional support for junior biomedical researchers. JAMA 2015;314:1175–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carnes M, Devine PG, Baier Manwell L, et al. The effect of an intervention to break the gender bias habit for faculty at one institution: a cluster randomized, controlled trial. Acad Med 2015;90:221–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowen R, Rajgopal S, Venkatachalam M. Accounting discretion, corporate governance, and firm performance. Contemp Account Res 2008;25:310–405. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gray K, Neville A, Kaji AH, et al. Career goals, salary expectations, and salary negotiation among male and female general surgery residents. JAMA Surg 2019;154:1023–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ley TJ, Hamilton BH. Sociology. The gender gap in NIH grant applications. Science 2008;322:1472–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliveira DFM, Ma Y, Woodruff TK, Uzzi B. Comparison of national institutes of health grant amounts to first-time male and female principal investigators. JAMA 2019;321:898–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ginther DK, Kahn S, Schaffer WT. Gender, race/ethnicity, and national institutes of health R01 research awards: is there evidence of a double bind for women of color? Acad Med 2016;91:1098–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoppe TA, Litovitz A, Willis KA, et al. Topic choice contributes to the lower rate of NIH awards to African-American/black scientists. Sci Adv 2019;5:eaaw7238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwedt TJ, Shapiro RE. Funding of research on headache disorders by the national institutes of health. Headache 2009;49:162–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hechtman LA, Moore NP, Schulkey CE, et al. NIH funding longevity by gender. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115:7943–7948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fox MF. Women, science, and academia: graduate education and careers. Gender Society 2001;15(5):654–666. [Google Scholar]

- 32.West JD, Jacquet J, King MM, Correll SJ, Bergstrom CT. The role of gender in scholarly authorship. PLoS One 2013;8:e66212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pakpoor J, Liu L, Yousem D. A 35-year analysis of sex differences in neurology authorship. Neurology 2018;90:472–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clark J, Horton R. What is the lancet doing about gender and diversity? Lancet 2019;393:508–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Babcock LLS. Women Don't Ask: The High Cost of Avoiding Negotiation-And Positive Strategies for Change. New York: Bantam; 2007:272. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silver JK, Poorman JA, Reilly JM, Spector ND, Goldstein R, Zafonte RD. Assessment of women physicians among authors of perspective-type articles published in high-impact pediatric journals. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e180802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lerchenmueller MJ, Sorenson O, Jena AB. Gender differences in how scientists present the importance of their research: observational study. BMJ 2019;367:l6573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nittrouer CL, Hebl MR, Ashburn-Nardo L, Trump-Steele RCE, Lane DM, Valian V. Gender disparities in colloquium speakers at top universities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park SM. Research, teaching, and service: why Shouldn't women's work count? J Higher Educ 1996;67:46. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loder E, Burch R. Underrepresentation of women among authors of invited commentaries in medical journals-where are the female editorialists? JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e1913665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silver JK, Bank AM, Slocum CS, et al. Women physicians underrepresented in American Academy of Neurology recognition awards. Neurology 2018;91:e603–e614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boiko JR, Anderson AJM, Gordon RA. Representation of women among academic grand rounds speakers. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:722–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stentz NC, Griffith KA, Perkins E, Jones RD, Jagsi R. Fertility and childbearing among American female physicians. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2016;25:1059–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kemkes-Grottenthaler A. Postponing or rejecting parenthood? Results of a survey among female academic professionals. J Biosoc Sci 2003;35:213–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farkas AH, Bonifacino E, Turner R, Tilstra SA, Corbelli JA. Mentorship of women in academic medicine: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34:1322–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blood EA, Ullrich NJ, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, et al. Academic women faculty: are they finding the mentoring they need? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:1201–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.NIH Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tool (RePORT). 2020. Available at: projectreporter.nih.gov/reporter.cfm. Accessed March 14, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Career Development Awards. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Web site. Available at: www.ninds.nih.gov/Funding/Training-Career-Development/Career-Development-Awards. Accessed March 14, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Travis EL, Doty L, Helitzer DL. Sponsorship: a path to the academic medicine C-suite for women faculty? Acad Med 2013;88:1414–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Research Supplements to Promote Diversity in Health-Related Research. Contacts, Submission Dates and Special Instructions for PA-16-288. NIH Grants & Funding Web site. Available at: grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/contacts/PA-15-322_contacts.html. Accessed March 18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Fund to Retain Clinical Scientists, Medical Research. Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Web site. Available at: www.ddcf.org/what-we-fund/medical-research/goals-and-strategies/encourage-and-develop-clinical-research-careers/fund-to-retain-clinical-scientists/2020. Accessed March 14, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 52.DeBord LC, Patel V, Braun TL, Dao H Jr. Social media in dermatology: clinical relevance, academic value, and trends across platforms. J Dermatolog Treat 2019;30:511–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cabrera D. Mayo Clinic Includes Social Media Scholarship Activities in Academic Advancement: Mayo Clinic Social Media Network; 2016. Available at: https://socialmedia.mayoclinic.org/2016/05/25/mayo-clinic-includes-social-media-scholarship-activities-in-academic-advancement/. Accessed March 14, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schor NF. Women in medical school leadership positions: implications for research. Ann Neurol 2019;85:789–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yin HL, Gabrilove J, Jackson R, et al. Sustaining the clinical and translational research workforce: training and empowering the next generation of investigators. Acad Med 2015;90:861–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Comeau DL, Escoffery C, Freedman A, Ziegler TR, Blumberg HM. Improving clinical and translational research training: a qualitative evaluation of the atlanta clinical and translational science institute KL2-mentored research scholars program. J Investig Med 2017;65:23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jagsi R, DeCastro R, Griffith KA, et al. Similarities and differences in the career trajectories of male and female career development award recipients. Acad Med 2011;86:1415–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jagsi R, Motomura AR, Griffith KA, Rangarajan S, Ubel PA. Sex differences in attainment of independent funding by career development awardees. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:804–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Plank-Bazinet JL, Bunker Whittington K, Cassidy SK, et al. Programmatic efforts at the national institutes of health to promote and support the careers of women in biomedical science. Acad Med 2016;91:1057–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peek ME, Kim KE, Johnson JK, Vela MB. “URM candidates are encouraged to apply”: a national study to identify effective strategies to enhance racial and ethnic faculty diversity in academic departments of medicine. Acad Med 2013;88:405–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Flores G, Mendoza FS, DeBaun MR, et al. Keys to academic success for under-represented minority young investigators: recommendations from the research in academic pediatrics initiative on diversity (RAPID) national advisory committee. Int J Equity Health 2019;18:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]