Abstract

Objective

To explore long-term predictors of avoiding β-amyloid (Aβ) deposition and maintaining unimpaired cognition as outcomes in the oldest old.

Methods

In a longitudinal observational cohort study, 100 former participants of the Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study (GEMS; 2000–2008) completed biannual Pittsburgh compound B-PET imaging and annual clinical-cognitive evaluations beginning in 2010. Most recent Aβ status and cognitive status were selected for each participant. Longitudinal outcomes included change in serial Aβ and cognitive tests. Baseline predictors from GEMS included neuropsychological tests, daily functioning, APOE genotype, lifestyle variables, occupational measures, health history, sleep, subjective memory, physical and cognitive activities, depressive symptoms, and physical performance and health indices, among others.

Results

Mean age at the last cognitive evaluation was 92.0 (range 86–100) years. Mean follow-up time from baseline to last measured Aβ status was 12.3 (SD 1.9) years and to last cognitive evaluation was 14.1 (SD 1.9) years. The APOE*2 allele predicted last Aβ status (n = 34 Aβ negative vs n = 66 Aβ positive). Baseline cognition predicted cognitive status (n = 30 unimpaired vs n = 70 impaired). Predictors of cognitive status among Aβ-positive participants only (n = 14 normal cognition vs n = 52 impaired) were baseline cognitive test scores and smoking history. Baseline pulse pressure predicted longitudinal Aβ increase; paid work engagement and life satisfaction predicted less cognitive decline.

Conclusions

The APOE*2 allele and lower pulse pressure predict resistance to Aβ deposition in advanced aging. Cognitive test scores 14 years prior, likely reflecting premorbid abilities, predict cognitive status and maintenance of unimpaired cognition in the presence of Aβ. Several lifestyle factors appear protective.

As life expectancy around the industrialized globe increases,1 the drive to understand and influence how humans age has become pressing, particularly regarding maintenance of healthy cognitive functioning. The prevalence of dementia, including Alzheimer disease (AD), is highly age dependent, and estimates range from 15% to >40% by 90 years of age.2–4 Prevalence of significant β-amyloid (Aβ) deposition in the brain is also highly age dependent and ranges from 44% to 71% by 90 years of age among people without dementia.5 However, dementia is far from an inevitability in advanced aging; little is known about determinants of successful brain and cognitive aging, including determinants of the absence of AD pathology.

A recently proposed framework6 for conceptualizing and studying healthy cognitive aging outcomes distinguishes resistance to accumulating AD pathology from resilience in the presence of AD pathology. Evidence for resistance, therefore, is absence of or lower-than-expected levels of AD pathology, whereas evidence for resilience is better-than-expected cognitive performance relative to the degree of AD pathology. Because both Aβ deposition and cognitive impairment are highly prevalent in the 9th and 10th decades of life, studying exceptions to the rule in this life stage is well suited to applying the framework of resistance and resilience.

The goal of this study was to explore a broad array of long-term predictors of low Aβ pathology burden and maintenance of cognitive function in advanced aging. We did this in 100 participants who averaged 92 years of age at the last individual clinical follow-up. These participants all completed the 8-year Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study (GEMS)7 and were then followed up further with amyloid imaging and clinical-cognitive evaluations, up to another 8 years. Baseline predictors of the GEM study were investigated vis-à-vis long-term amyloid imaging and cognitive outcomes. For each participant, we selected outcome visits as long into follow-up as possible and then analyzed results by 3 nonmutually exclusive outcome groupings: (1) absence vs presence of Aβ, regardless of cognitive status (i.e., resistance to AD pathology); (2) absence vs presence of cognitive impairment, regardless of Aβ status; and (3) absence vs presence of cognitive impairment among people with Aβ deposition (i.e., resilience in coping with AD pathology). Finally, we investigated baseline predictors of longitudinal change in global Aβ and serial cognitive test performance as outcomes.

Methods

Participants

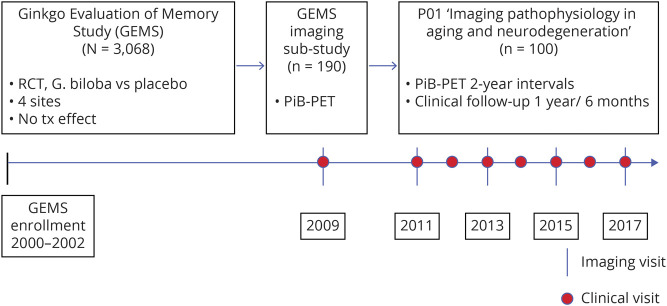

One hundred participants (mean age 92 years, range 86–100 years) were included in this study. They had completed participation in the Pittsburgh site of GEMS, a randomized controlled trial of 240 mg daily Gingko biloba vs placebo for dementia prevention from 2000 to 2008. The primary study outcome of incident dementia and the secondary outcome of cognitive decline were both negative.7,8 Of the n = 3,068 total participants enrolled, the Pittsburgh site of GEMS enrolled n = 966, of whom n = 671 completed the trial. Of those completers, n = 190 were invited to take part in the GEMS Imaging Sub-Study in 2009.9 In 2010 to 2011, n = 100 of those participants continued to be followed up in a subsequent neuroimaging study10 with serial neuroimaging and clinical-cognitive evaluations to the present time (figure). Compared to all 671 Pittsburgh site participants who completed the GEMS protocol and did not reach a dementia endpoint, the 2009 Imaging Sub-Study participants were slightly younger but otherwise comparable in sex, race, education, APOE*4 status, estimated premorbid IQ, and estimated income by zip code (p > 0.05). Compared to those participants from the Imaging Sub-Study who did not go on to the subsequent longitudinal follow-up study, those who did were comparable in age, sex, race, education, and proportion of APOE*2 carriers, but they had higher Mini-Mental State Examination scores (27.9 vs 27.1, p = 0.01), lower proportion of Aβ positivity (45.5% vs 65.3%, p = 0.004), and lower proportion of APOE*4 carriers (15.1% vs 26.4%, p = 0.04).

Figure. Timeline of study procedures and participant selection and flow through the GEMS, 2009 GEMS Imaging Sub-Study, and current imaging and clinical follow-up study.

GEMS = Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study; PiB = Pittsburgh compound B; RCT = randomized controlled trial.

Inclusion criteria for GEMS (2000–2002 enrollment) were age ≥75 years and residing in 1 of the 4 catchment site areas. Exclusion criteria were prevalent dementia; taking warfarin, 400 IU vitamin E, or medication with high anticholinergic load; history of bleeding disorders, severe depression, or Parkinson disease; abnormal metabolic laboratory values, liver function tests, vitamin B12, or platelets; or disease-related life expectancy <5 years.7

The inclusion criterion for the present longitudinal neuroimaging study was completion of GEMS/GEMS Imaging Sub-Study. Exclusion criteria were contraindications to MRI/PET and dementia at study entry (2010–2011).

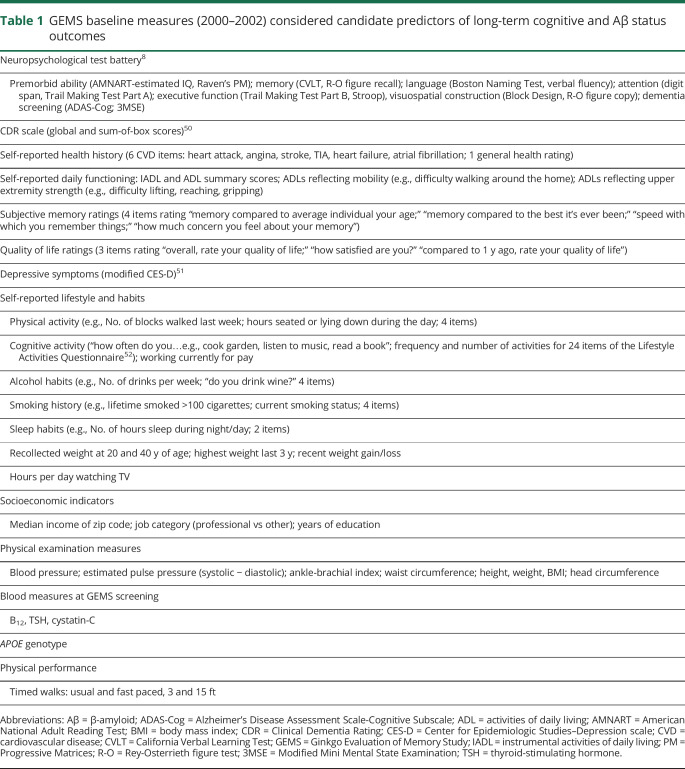

Predictors from GEMS baseline

A wide range of variables measured at GEMS enrollment (2000–2002) were investigated as potential predictors of long-term cognitive and brain Aβ outcomes. Categories of measures included neuropsychological test performance, informant-based daily functioning, self-reported health history, subjective memory/quality of life/depressive symptom ratings, lifestyle and habits, socioeconomic indicators, physical examination measures, laboratory screening measures, and APOE genotype (table 1). APOE genotyping was performed on isolated DNA from blood as described previously.11

Table 1.

GEMS baseline measures (2000–2002) considered candidate predictors of long-term cognitive and Aβ status outcomes

Outcomes

Pittsburgh compound B-PET imaging

Before PET imaging visits, a spoiled gradient recalled magnetic resonance scan was obtained for each participant for MRI-PET image coregistration and anatomic region of interest definition, as previously described.12 PET imaging was conducted with a Siemens/CTI ECAT HR+ (Malvern, PA; 3D mode, 15.2-cm field of view, 63 planes, reconstructed image resolution ≈6 mm). High-specific-activity [11C]Pittsburgh compound B (PiB), produced as previously described, was synthesized by a standard method.13,14 The PiB-PET data were acquired over the 50- to 70-minute postinjection interval in a dynamic series of 6 × 500-second frames as previously described.13,15

Analysis of the PiB-PET data was performed on summed PET images in a manner consistent with established methods.16 Before the acquisition frames were summed, the dynamic PET images were visually inspected by an experienced analyst for significant intraframe motion, and if necessary, motion correction was applied on a frame-by-frame basis as previously described.13 ROIs were separately hand drawn on a coregistered MRI and included the following regions: frontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, striatum (caudate and anterior putamen), precuneus/posterior cingulate cortex, parietal cortex, lateral temporal cortex, and cerebellum.12,17 The region of interest definitions were transferred to the coregistered summed PET images and used to compute regional standardized uptake value ratios (SUVR) normalized to cerebellar gray matter.16 A global amyloid load index was determined by calculating a voxel-weighted average of the regions listed previously, excluding the cerebellum. A partial volume–corrected cutoff of 1.67 SUVR determined PiB negative from PiB positive.18 PiB-PET imaging occurred in 2009 in the year after the GEMS trial and thereafter every ≈2 years (figure).

Clinical-cognitive evaluations

Clinical-cognitive evaluations included the GEMS diagnostic neuropsychological test battery8 (table 1), as well as the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale, a physical and neurologic examination, the Geriatric Depression Scale, and self-reported health history, as described previously.10 If in-person evaluations were not feasible, a phone interview was conducted in a small number of cases using the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status.19 Clinical-cognitive evaluations occurred annually until 2015 and every 6 months thereafter (figure). Cognitive diagnosis was determined for every study visit by multidisciplinary consensus conference, with DSM-IV criteria used for dementia and Peterson/Winblad criteria used for mild cognitive impairment.20,21 Cognitive diagnosis was the basis for cognitive status (i.e., cognitively unimpaired vs impaired) used in the outcome groupings, reported below.

Outcome groupings

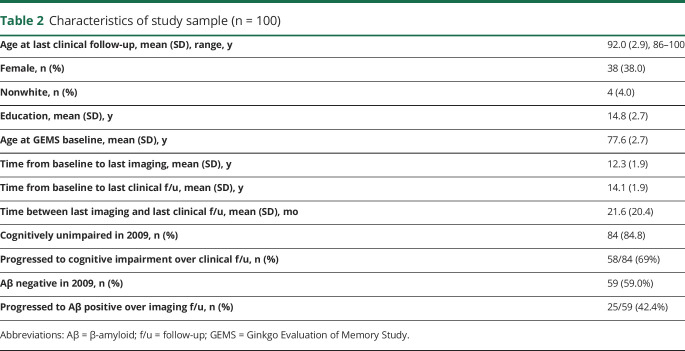

For each participant, brain Aβ status and cognitive status were determined by the last available neuroimaging visit and by the last available clinical-cognitive evaluation, respectively. Thus, the duration in years from baseline to outcome differed among participants and differed slightly between the amyloid imaging and the cognitive outcome groupings (table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of study sample (n = 100)

Longitudinal outcomes

Longitudinal outcomes included global PiB SUVR and 4 neuropsychological tests selected as representative of key domains in AD: verbal and visual memory (California Verbal Learning Test [CVLT] delayed recall; Rey-Osterrieth figure delayed recall), language (semantic fluency), and executive functions (Trail Making Test Part B). Longitudinal outcomes were measured from 2009 to 2017 and included 2 to 4 serial PiB scans and 2 to 13 serial neuropsychological evaluations.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and participant consents

The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Analysis

Given the large number of candidate baseline predictors, analyses were considered exploratory, and no type I error corrections were made. Univariate logistic regression was used to investigate baseline predictors of Aβ and cognitive outcome groups. Generalized estimating equations were used to model longitudinal cognitive scores and longitudinal global Aβ. Univariate predictors significant at p < 0.10 were considered for inclusion in subsequent multivariate logistic regression or generalized estimating equations models, respectively. Then stepwise selection was used to identify significant predictors of outcomes. A significance level of p = 0.05 was required to allow an effect into and to remain in the model. Logistic regression models included age, sex, education, and time from baseline as forced variables. Finally, to evaluate change over time in outcomes in the generalized estimating equations models, interaction terms with time were added to each significant predictor in stepwise models for longitudinal outcomes. Analyses were conducted with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Data availability

Anonymized data analyzed in the current study will be made available on request by qualified investigators.

Results

Table 2 shows characteristics of the whole study sample, with mean age of 92 years at last clinical follow-up and mean follow-up time from baseline of 14 years to last clinical visit and 12 years to last PiB-PET imaging visit. The mean age at which GEMS baseline predictor data were collected was 77.6 years. Of note, mortality was 54% since 2011 (enrollment into the follow-up imaging study).

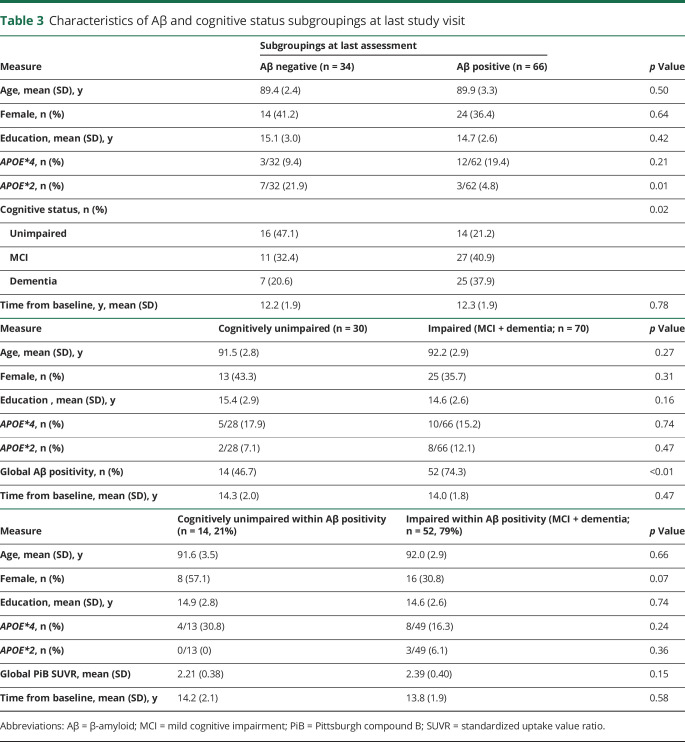

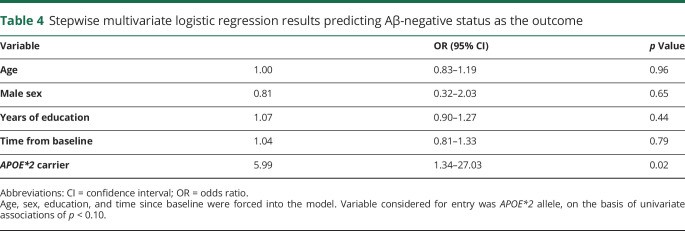

Outcome grouping 1: Aβ status, regardless of cognitive status

Table 3 shows demographic and APOE variables of subgroups by Aβ status at the last imaging visit, when 34% (n = 34) of participants were Aβ negative. These subgroups were not statistically different by age, sex, education, or APOE*4 status, although the expected trend toward higher Aβ positivity with APOE*4 was observed. The Aβ-negative subgroup had a higher proportion of APOE*2 carriers than the Aβ-positive subgroup (21.9% vs 4.8%, odds ratio [OR] 5.5, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.3–23.0, p = 0.01). Of the GEMS baseline predictors listed in table 1, the only significant univariate predictor of negative Aβ status was the APOE*2 allele, which remained significant after adjustment for demographics and time from baseline (OR 5.99, 95% CI 1.34–27.03; p = 0.02; table 4).

Table 3.

Characteristics of Aβ and cognitive status subgroupings at last study visit

Table 4.

Stepwise multivariate logistic regression results predicting Aβ-negative status as the outcome

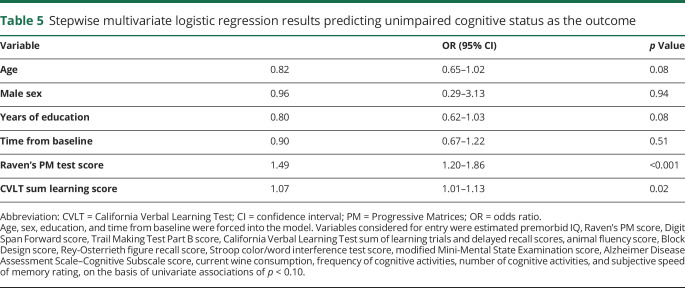

Outcome grouping 2: Cognitive status, regardless of Aβ status

Table 3 shows demographic and APOE variables of subgroups by cognitive status at the last clinical visit, when 30% (n = 30) had unimpaired (normal) cognition. These subgroups were not different by any demographic variable or APOE*4 or APOE*2 status. Candidate univariate baseline predictors (p < 0.10) of cognitively unimpaired status are listed in the footnote to table 5. A stepwise multivariate logistic model resulted in 2 predictors, Raven's Progressive Matrices (PM) test, a measure of premorbid cognitive ability and reasoning (OR 1.49, 95% CI 1.20–1.86; p < 0.001), and CVLT learning trials, a verbal memory measure (OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.01–1.13; p = 0.02) (table 5).

Table 5.

Stepwise multivariate logistic regression results predicting unimpaired cognitive status as the outcome

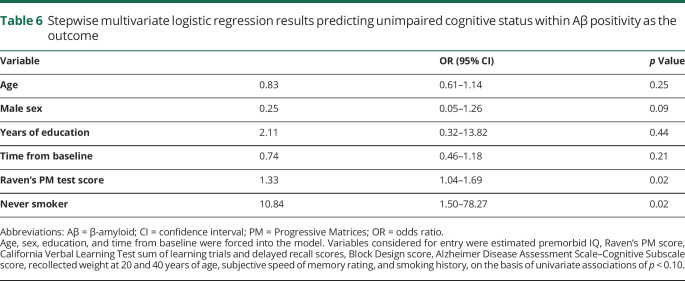

Outcome grouping 3: Cognitive status within Aβ positivity

Table 3 shows cognitive status subgroups within n = 66 Aβ-positive participants, when 21% (n = 14) were CU. Of note, the mean clinical follow-up time since the first positive Aβ scan observed for these 14 CU participants was 5.0 (range 0–8.4) years. This small subgroup was not different from cognitively impaired Aβ-positive participants by demographic variables or APOE genotype. Candidate univariate predictors (p < 0.10) of unimpaired cognition within Aβ positivity are listed in the footnote to table 6. In a stepwise multivariate model, never having smoked (OR 10.84, 95% CI 1.50–78.27; p = 0.02) and Raven's PM test score (OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.04–1.69; p = 0.02) were significant (table 6).

Table 6.

Stepwise multivariate logistic regression results predicting unimpaired cognitive status within Aβ positivity as the outcome

Longitudinal Aβ outcome, regardless of cognitive status

A stepwise selection model of all variables with p < 0.10 at the univariate level resulted in a multivariate model with TIA history, APOE*4 allele, worse Trail Making Test Part B performance, and higher pulse pressure predicting higher overall global PiB SUVR across time (multivariate model p < 0.05). Adding interaction terms resulted in a significant pulse pressure × time interaction such that higher pulse pressure predicted greater increase in global PiB over time (estimate 0.001, SE 0.0004; p < 0.01). Full results are given in supplemental table 1a and 1b (doi.org/10.5061/dryad.fxpnvx0nf).

Longitudinal cognitive outcomes, regardless of Aβ status

A stepwise selection model of all variables with p < 0.10 predicting longitudinal verbal memory scores at the univariate level resulted in a multivariate model with lower CDR sum of boxes scores, higher number of cognitive activities, absence of hypertension, better subjective memory rating, and female sex predicting higher overall longitudinal verbal memory scores (p < 0.05). Adding baseline predictors × time interaction terms resulted in no significant associations with change in verbal memory over time (p > 0.35; supplemental table 2a and 2b, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.fxpnvx0nf). Univariate predictors of longitudinal visual memory scores were candidates in the stepwise selection procedure, resulting in a multivariate model with Raven's PM score, engagement in paid work, and higher ankle-brachial index predicting better longitudinal visual memory scores (p < 0.01). Adding interaction terms resulted in a significant paid work × time interaction (estimate 0.24, SE 0.12; p < 0.05), indicating that paid work engagement (vs none) predicted less memory decline over time (supplemental table 3a and 3b, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.fxpnvx0nf). Univariate baseline predictors of longitudinal language test scores were candidates for the stepwise selection procedure, resulting in a multivariate model with a higher sum of cognitive activities, number of hours of daytime sleep, lower pulse pressure, and better subjective memory rating predicting better overall longitudinal language scores (p < 0.05). Adding interaction terms resulted in no significant predictors of change in language scores over time (p > 0.20) (supplemental table 4a and 4b, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.fxpnvx0nf). Finally, univariate baseline predictors of longitudinal executive function were candidates for the stepwise selection procedure, resulting in a multivariate model with Raven's PM score, younger baseline age, higher life satisfaction rating, faster 15-ft usual-pace walk, lower pulse pressure, and higher sum of cognitive activities predicting better overall longitudinal executive function scores (p < 0.05). Adding interaction terms resulted in a significant life satisfaction × time interaction (estimate 0.03, SE 0.01, p < 0.01), indicating that satisfaction with life (vs any other response choice) predicted less executive function decline over time (supplemental table 5a and 5b, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.fxpnvx0nf).

Longitudinal cognitive outcomes, within Aβ positivity

Among the n = 66 participants with Aβ positivity at the last scan, candidate univariate baseline predictors of longitudinal verbal and visual memory are listed in supplemental tables 6a and 7a (doi.org/10.5061/dryad.fxpnvx0nf), respectively. Better subjective memory ratings, higher frequency of cognitive activities, and lower systolic blood pressure predicted better overall verbal memory over time in a multivariate model (p < 0.05), but there were no significant interaction terms with time (p > 0.09) (supplemental table 6b, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.fxpnvx0nf). Predicting better visual memory over time in a stepwise model were higher subjective memory ratings, higher Raven's PM score, lower CDR score, nonsmoker status, and no reported difficulty getting out of a chair or bed (p < 0.05). Only worse subjective speed of memory predicted change (faster decline) in visual memory (estimate 0.18, SE 0.09; p < 0.05) (supplemental table 7b, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.fxpnvx0nf). Candidate univariate baseline predictors for language (semantic fluency) and executive functions (Trail Making Test Part B) are presented in supplemental tables 8a and 9a (doi.org/10.5061/dryad.fxpnvx0nf), respectively. Multivariate stepwise models selected higher number of cognitive activities and higher thyroid-stimulating hormone predicting better overall longitudinal language scores (p < 0.01), while number of cognitive activities, Raven's PM test performance, lower age, higher ankle-brachial index, and no instrumental activities of daily living impairment predicted better overall executive function scores (p < 0.01). However, none of these baseline predictors interacted significantly with time to predict change in language or executive function scores (p > 0.08) (supplemental tables 8b and 9b, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.fxpnvx0nf).

Discussion

We investigated long-term predictors of resistance to Aβ and cognitive resilience in the oldest old. Studying advanced aging is well suited to investigating resistance to brain disease markers, defined here as absence of or lower-than-expected AD pathology, because this is the less common outcome in the ninth decade of life.5 Our main findings from predictions of the last measured outcomes (i.e., cognitive and Aβ status) are that (1) the APOE*2 allele predicted the absence of significant Aβ pathology (resistance); (2) performance on cognitive tests from 14 years prior was predictive of maintaining healthy cognition; and (3) healthy cognition within Aβ positivity (resilience) was similarly predicted by baseline cognitive test performance, as well as never having smoked. Main findings from longitudinal analyses are that (4) baseline vascular health factors and APOE*4 predicted overall Aβ deposition across time, including lower baseline pulse pressure as protective against Aβ increases over time (resistance); and (5) few baseline measures predicted differential change in cognition over time; these included current paid work engagement and life satisfaction, both protective against memory decline in the whole cohort. Among the Aβ-positive subgroup, better baseline subjective memory ratings predicted less memory decline over time.

The finding that the APOE*2 allele is protective against significant Aβ pathology on imaging is consistent with other studies with younger and broader age ranges. Grothe et al.22 reported lower regional amyloid load with AV45-PET among APOE*2 carriers compared to E3/E3 in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, with a mean age of 73 years. Also using Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative data, Lim and Mormino23 examined longitudinal imaging over 2 years and reported a trend toward a slower rate of Aβ accumulation in APOE*2 carriers. However, no effect of APOE*2 was found on Aβ load among Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study participants with a mean age of 70 years.24 In a meta-analysis estimating the prevalence of amyloid pathology on imaging5 from combined data across 55 studies, APOE*2 status was associated with reduced odds of Aβ positivity at age 70 years; while this effect was estimated to hold across older ages, the actual number of participants >89 years of age in the meta-analysis was limited to n = 46. The present findings replicate and extend the literature on APOE*2 in a larger sample of oldest old. Recently, a study of an unusual Columbian presenilin 1 mutation carrier living without AD dementia at age 70 years, with 2 copies of the APOE*3 Christchurch (R136S) mutation, points to the intervention potential of future APOE-directed therapy because both APOE*3ch and APOE*2 bind poorly to heparan sulfate proteoglycans, making this a druggable target.25 Although the APOE*3ch variant lowers Aβ42 aggregation in vitro similar to the effect of APOE*2, the recent Columbian case study showed very high levels of Aβ on PET imaging but limited tau and neurodegeneration, suggesting that the effect of APOE*3ch in vivo is downstream of Aβ deposition.

That vascular health factors and the APOE*4 allele predicted higher Aβ across time is consistent with previous studies, including several studies on APOE*4.5,26,27 Cardiovascular effects on Aβ accumulation may operate through reduced clearance via cerebral blood flow or increased small vessel stiffness and compromised blood-brain barrier integrity. We also note that an earlier report from this same cohort found that pulse wave velocity and arterial stiffness in 2011 were associated with Aβ positivity and Aβ accumulation from 2009 to 2011.28 Current results extend those findings to much longer prediction and observation periods, because baseline pulse pressure was measured in 2000 to 2002 and Aβ accumulation was measured across 2009 to 2017.

Baseline neuropsychological tests predicted long-term cognitive outcomes. In particular, baseline performance on a measure reflective of estimated lifelong fluid cognitive abilities was the most consistently predictive cognitive measure. These findings are consistent with the theory of cognitive reserve,29 that is, that aspects of individual differences in premorbid cognitive abilities contribute to maintaining cognitive health in the face of brain pathology. That cognitive test performance was not, by and large, predictive of future Aβ deposition supports the interpretation that baseline tests generally reflect premorbid individual differences in abilities rather than downstream effects of very early or latent AD pathology. The mechanisms of this protection are unclear from this study, but possibilities for consideration and further study include neurobiological resilience factors, socioeconomic advantage, systemic health factors, or possible influence by selection bias factors (see limitations below).30 Regarding possible neural mechanisms of premorbid resilience, recent research approaches include investigating gray matter volume, whole-brain or regional patterns, cortical surface area and thickness, PET measures of synaptic integrity, or white matter microstructure.30 For example, a recent study applied structural equation modeling in a large longitudinal cohort, observing evidence for a causal pathway from education and lifetime occupation to systemic vascular health to microstructural white matter integrity to cortical thinning to cognitive decline.31 These are important directions for further research.

Overall, we found some evidence, although limited, of protection from lifestyle variables against Aβ or cognitive impairment in the oldest old, in contrast to stronger evidence from studies in younger-old populations regarding dementia risk.32–35 Never having smoked predicted maintenance of healthy cognition in the presence of Aβ deposition. Other studies have found smoking to be a risk factor for dementia and cognitive decline.36,37 Engagement in paid work is consistent with the broader pattern of significant predictors in these analyses reflecting cognitive reserve and cognitive activities. Paid work has previously been reported as protective, independently of sex,38 and findings are consistent with larger studies linking occupational complexity39 and early retirement40 to cognitive outcomes in late life. Low life satisfaction has also been reported as predictive of dementia.41 Studies investigating sense of life purpose or meaning support the notion that psychological well-being captured by broad constructs may offer protection against poorer cognitive42 and vascular and mortality outcomes.43

Few studies have examined risk and protective factors in advanced aging. In one of the largest oldest-old cohorts, the 90+ Study, Corrada et al.44 reported that neither APOE*4 nor APOE*2 alleles were associated with incident dementia over 2 years, although APOE*4 was associated with prevalent dementia at baseline. Other studies also suggest a decreased impact of APOE*4 on dementia risk as people age into their 80s and 90s.45,46 Ganguli et al.46 found that the risk and protective factors for incident dementia in a population cohort with onset at <87 years of age, including APOE*4, were not significant for dementia onset at >87 years of age. In fact, no risk or protective factors could be detected in this age-of-onset range, despite accelerating incidence. The authors discuss the challenge of increased heterogeneity of neuropathology and decreased overlap between neuropathology and dementia in the oldest old.47,48 New studies targeting the oldest old with the explicit goal of advancing understanding in this age group are growing in importance as the global population ages.49

Limitations of this study include selection biases toward characteristics associated with willingness and eligibility to complete a long-term clinical trial and subsequent neuroimaging research program. These participants were mostly white, highly educated, and in good health in 2000 (mean age 75 years), without dementia in 2009 (mean age 84 years), and had an unusually large proportion of men (62%), limiting generalizability to other aging populations. Specifically, participants who agreed to and were eligible for study entry points were less likely to have Aβ deposition and the APOE*4 allele; thus, the findings may be underestimates of general aging population effects or at least limited in their external validity. This study was exploratory given the large number of candidate predictors and relatively small number, especially of the APOE genotype groups; independent confirmation is therefore important. Furthermore, the term prediction is not used in the strict statistical sense because there is no cross-validation to evaluate generalized predictive accuracy but rather in the context of sequential measurements in a longitudinal study design. An important difference from most other longitudinal aging studies is that we did not apply a time-to-event analysis. Rather, we selected the last available clinical-cognitive and PiB-PET status as outcomes, resulting in longer observational time, older ages at follow-up, and greater confidence in the stability of outcomes. Of note, the observation of a mean of 5 years of amyloid positivity among the Aβ-positive oldest-old participants with unimpaired cognition offers an opportunity to address questions of resilience.

We investigated long-term predictors of resistance to Aβ deposition and of cognitive resilience in the presence of Aβ pathology in the oldest old. The APOE*2 allele is protective against Aβ, and better cognitive test performance 14 years earlier, including measures of premorbid ability, predicts unimpaired cognitive status overall and for those with significant Aβ deposition. As advanced aging increases in developed countries and worldwide, well-designed studies are needed to better understand the variability of cognitive outcomes in the 10th decade of life, particularly to determine and confirm modifiable risk and protective factors.

Glossary

- Aβ

β-amyloid

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- AIBL

Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle

- CDR

Clinical Dementia Rating

- CI

confidence interval

- CVLT

California Verbal Learning Test

- DSM-IV

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition

- GEMS

Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study

- OR

odds ratio

- PiB

Pittsburgh compound B

- PM

Progressive Matrices

- SUVR

standardized uptake value ratio

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

Editorial, page 329

Study funding

This work was supported by NIH grants U01 AT000162 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine and the Office of Dietary Supplements and National Institute on Aging; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; P01 AG025204; AG030653; and AG041718.

Disclosure

B. Snitz, Y. Chang, D. Tudorascu, O. Lopez, and B. Lopresti report no disclosures. S. DeKosky is on advisory boards for Amgen and Cognition Therapeutics, chairs the Drug Monitoring Committee for Biogen, and is editor for Dementia. M. Carlson, A. Cohen, I. Kamboh, and H. Aizenstein report no disclosures. W. Klunk is a coinventor of PiB and, as such, has a financial interest in this license agreement. GE Healthcare provided no grant support for this study. L. Kuller reports no disclosures. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Kochanek KD, Arias E, Bastian BA. The effect of changes in selected age-specific causes of death on non-Hispanic white life expectancy between 2000 and 2014. NCHS Data Brief 2016:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lobo A, Launer L, Fratiglioni L, et al. Prevalence of dementia and major subtypes in Europe: a collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurology 2000;54:S4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lucca U, Tettamanti M, Logroscino G, et al. Prevalence of dementia in the oldest old: the Monzino 80-plus population based study. Alzheimers Dement 2015;11:258–270.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corrada M, Brookmeyer R, Berlau D, Paganini-Hill A, Kawas C. Prevalence of dementia after age 90: results from the 90+ Study. Neurology 2008;71:337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jansen WJ, Ossenkoppele R, Knol DL, et al. Prevalence of cerebral amyloid pathology in persons without dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2015;313:1924–1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Vemuri P. Resistance vs resilience to Alzheimer disease: clarifying terminology for preclinical studies. Neurology 2018;90:695–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeKosky ST, Williamson JD, Fitzpatrick AL, et al. Ginkgo biloba for prevention of dementia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008;300:2253–2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snitz BE, O'Meara ES, Carlson MC, et al. Ginkgo biloba for preventing cognitive decline in older adults: a randomized trial. JAMA 2009;302:2663–2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathis CA, Kuller LH, Klunk WE, et al. In vivo assessment of amyloid-β deposition in nondemented very elderly subjects. Ann Neurol 2013;73:751–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez OL, Becker JT, Chang Y, et al. Amyloid deposition and brain structure as long-term predictors of MCI, dementia, and mortality. Neurology 2018;90:e1920–e1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamboh MI, Aston CE, Hamman RF. The relationship of APOE polymorphism and cholesterol levels in normoglycemic and diabetic subjects in a biethnic population from the San Luis Valley, Colorado. Atherosclerosis 1995;112:145–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen AD, Price JC, Weissfeld LA, et al. Basal cerebral metabolism may modulate the cognitive effects of Abeta in mild cognitive impairment: an example of brain reserve. J Neurosci 2009;29:14770–14778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price JC, Klunk WE, Lopresti BJ, et al. Kinetic modeling of amyloid binding in humans using PET imaging and Pittsburgh compound-B. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2005;25:1528–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson AA, Garcia A, Chestakova A, Kung H, Houle S. A rapid one-step radiosynthesis of the β-amyloid imaging radiotracer N-methyl-[11C] 2-(4′-methylaminophenyl)-6-hydroxybenzothiazole ([11C]-6-OH-BTA-1). J Labelled Compounds Radiopharm Official J Int Isotope Soc 2004;47:679–682. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McNamee RL, Yee S-H, Price JC, et al. Consideration of optimal time window for Pittsburgh compound B PET summed uptake measurements. J Nucl Med 2009;50:348–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopresti BJ, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, et al. Simplified quantification of Pittsburgh compound B amyloid imaging PET studies: a comparative analysis. J Nucl Med 2005;46:1959–1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosario BL, Weissfeld LA, Laymon CM, et al. Inter-rater reliability of manual and automated region-of-interest delineation for PiB PET. Neuroimage 2011;55:933–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen AD, Mowrey W, Weissfeld LA, et al. Classification of amyloid-positivity in controls: comparison of visual read and quantitative approaches. Neuroimage 2013;71:207–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brandt J, Spencer M, Folstein M. The telephone interview for cognitive status. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1988;1:111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med 2004;256:183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment-beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med 2004;256:240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grothe MJ, Villeneuve S, Dyrba M, Bartrés-Faz D, Wirth M; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Multimodal characterization of older APOE2 carriers reveals selective reduction of amyloid load. Neurology 2017;88:569–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim YY, Mormino EC; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. APOE genotype and early β-amyloid accumulation in older adults without dementia. Neurology 2017;89:1028–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim YY, Williamson R, Laws SM, et al. Effect of APOE genotype on amyloid deposition, brain volume, and memory in cognitively normal older individuals. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;58:1293–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arboleda-Velasquez JF, Lopera F, O'Hare M, et al. Resistance to autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease in an APOE3 Christchurch homozygote: a case report. Nat Med 2019:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gottesman RF, Schneider AL, Zhou Y, et al. Association between midlife vascular risk factors and estimated brain amyloid deposition. JAMA 2017;317:1443–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santos CY, Snyder PJ, Wu W-C, Zhang M, Echeverria A, Alber J. Pathophysiologic relationship between Alzheimer's disease, cerebrovascular disease, and cardiovascular risk: a review and synthesis. Alzheimers Dement Diagn Assess Dis Monit 2017;7:69–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughes TM, Kuller LH, Barinas-Mitchell EJ, et al. Arterial stiffness and β-amyloid progression in nondemented elderly adults. JAMA Neurol 2014;71:562–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stern Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:1006–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stern Y, Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Bartrés-Faz D, et al. Whitepaper: defining and investigating cognitive reserve, brain reserve, and brain maintenance. Alzheimers Dement 2018;S1552-5260:33491–33495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vemuri P, Lesnick TG, Knopman DS, et al. Amyloid, vascular, and resilience pathways associated with cognitive aging. Ann Neurol 2019;86:866–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baumgart M, Snyder HM, Carrillo MC, Fazio S, Kim H, Johns H. Summary of the evidence on modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia: a population-based perspective. Alzheimers Dement 2015;11:718–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marioni RE, van den Hout A, Valenzuela MJ, Brayne C, Matthews FE. Active cognitive lifestyle associates with cognitive recovery and a reduced risk of cognitive decline. J Alzheimers Dis 2012;28:223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown BM, Peiffer J, Taddei K, et al. Physical activity and amyloid-β plasma and brain levels: results from the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle Study of Ageing. Mol Psychiatry 2013;18:875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deckers K, van Boxtel MP, Schiepers OJ, et al. Target risk factors for dementia prevention: a systematic review and Delphi consensus study on the evidence from observational studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015;30:234–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rusanen M, Rovio S, Ngandu T, et al. Midlife smoking, apolipoprotein E and risk of dementia and Alzheimer's disease: a population-based cardiovascular risk factors, aging and dementia study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2010;30:277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitmer RA, Sidney S, Selby J, Johnston SC, Yaffe K. Midlife cardiovascular risk factors and risk of dementia in late life. Neurology 2005;64:277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujiwara Y, Shinkai S, Kobayashi E, et al. Engagement in paid work as a protective predictor of basic activities of daily living disability in Japanese urban and rural community-dwelling elderly residents: an 8-year prospective study. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2016;16:126–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andel R, Crowe M, Pedersen NL, et al. Complexity of work and risk of Alzheimer's disease: a population-based study of Swedish twins. J Gerontol Ser B: Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2005;60:P251–P258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rohwedder S, Willis RJ. Mental retirement. J Econ Perspect 2010;24:119–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peitsch L, Tyas SL, Menec VH, John PDS. General life satisfaction predicts dementia in community living older adults: a prospective cohort study. Int Psychogeriatr 2016;28:1101–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Effect of a purpose in life on risk of incident Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older persons. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67:304–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohen R, Bavishi C, Rozanski A. Purpose in life and its relationship to all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 2016;78:122–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corrada MM, Paganini-Hill A, Berlau DJ, Kawas CH. Apolipoprotein E genotype, dementia, and mortality in the oldest old: the 90+ Study. Alzheimers Dement 2013;9:12–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Juva K, Verkkoniemi A, Viramo P, et al. APOE ε4 does not predict mortality, cognitive decline, or dementia in the oldest old. Neurology 2000;54:412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ganguli M, Lee CW, Snitz BE, Hughes TF, McDade E, Chang CCH. Rates and risk factors for progression to incident dementia vary by age in a population cohort. Neurology 2015;84:72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.James BD, Bennett DA, Boyle PA, Leurgans S, Schneider JA. Dementia from Alzheimer disease and mixed pathologies in the oldest old. JAMA 2012;307:1798–1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corrada M, Berlau DJ, Kawas CH. A population-based clinicopathological study in the oldest-old: the 90+ Study. Curr Alzheimer Res 2012;9:709–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Legdeur N, Badissi M, Carter SF, et al. Resilience to cognitive impairment in the oldest-old: design of the EMIF-AD 90+ Study. BMC Geriatr 2018;18:289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993;43:2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carlson MC, Parisi JM, Xia J, et al. Lifestyle activities and memory: variety may be the spice of life: the Women's Health and Aging Study II. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2012;18:286–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data analyzed in the current study will be made available on request by qualified investigators.