Abstract

Background

There is no standard of care with respect to the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) in resectable malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM). We performed an intention-to-treat analysis with data from a single institution and the National Cancer Database (NCDB) to identify whether the use of NAC impacts survival in resectable MPM.

Methods

Patients with MPM who had surgery with curative intent at Duke University from 1995 to 2017 were selected, and the 2004–2015 NCDB was used to identify MPM patients with clinical stage I–IIIB who underwent definitive surgery. For both cohorts, patients were stratified by receipt of NAC. Primary outcomes were overall survival and postresection survival (RS), which were estimated using Kaplan-Meier and multivariable Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

A total of 257 patients met inclusion criteria in the Duke cohort. Compared with immediate resection (IR), NAC was associated with similar overall survival but an increased risk for postresection mortality in both unmatched (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] = 1.85, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.21 to 2.83) and propensity-matched (HR = 1.62, 95% CI = 1.03 to 2.55) cohorts. A total of 1949 NCDB patients were included: 1597 (81.9%) IR and 352 (18.1%) NAC. RS was worse for patients undergoing NAC in both unmatched (HR = 1.85, 95% CI = 1.21 to 2.83) and propensity-matched (HR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.06 to 1.57) analyses compared with patients receiving IR.

Conclusions

In this intention-to-treat study, NAC was associated with worse RS compared with IR in patients with MPM. The risks and benefits of induction therapy should be weighed before offering it to patients with resectable MPM.

Patients with locally advanced malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) appear to benefit from surgical treatment provided that at least a microscopically margin-positive resection is possible (1–3). The oncologic value of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) for MPM is one of the most debated management strategies, and there are no consensus guidelines on its use for patients who are surgical candidates. The recommendation for the use of platinum-based NAC in combination with pemetrexed is based on two randomized trials published in 2003 (4) and 2005 (4,5), which demonstrated a longer median overall survival (OS) and time to progression among those receiving neoadjuvant therapy with cisplatin and pemetrexed compared with those receiving cisplatin alone. However, it is notable that an inclusion criterion for these trials was that patients could not be candidates for curative surgery. There are no prospective controlled trials comparing NAC and upfront surgery with or without adjuvant therapy. Nevertheless, in current clinical practice, this chemotherapeutic regimen has been adopted in the neoadjuvant setting to allow for downstaging and, hence, increase the macroscopic complete resection rate in curative-intent surgery as well as possibly induce remission, especially as the survival benefit of dual agent chemotherapy has been tested in prospective, randomized trials while the benefit of definitive surgery has not given the premature conclusion of the MARS feasibility trial (6). In more recent studies, however, the response rate to NAC has been documented to be low with very few cases having a complete response (5,7) and a considerable fraction of patients having a poor response to chemotherapy or demonstrating continued tumor progression (8). Thus, although originally resectable and with adequate performance status, they become ineligible for surgery because of health deterioration or have an incomplete macroscopically margin-positive resection, a known prognostic factor for worse survival (7,9). Moreover, whereas pathologic complete response in many cancers is correlated with survival outcomes, this remains unclear in MPM (10). The current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines reflect this gap in clinical certainty by recommending either induction chemotherapy or surgery for medically operable patients with MPM presenting with stage I–III disease (11). We performed an intention-to-treat analysis on both an institutional and a national database to compare the outcomes of patients with resectable MPM treated with NAC followed by curative-intent surgery vs immediate resection (IR) after diagnosis.

Methods

Duke Cohort: Patient Selection

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Duke University Medical Center, and the need for individual patient consent was waived. This study has two parts: study of the Duke institutional data with a propensity-matched analysis and an analysis of a national database, including propensity score matching, to corroborate the findings of our institutional data. In the first part of the study, the pathology database at Duke University was used to identify patients who underwent surgery with curative intent for MPM between January 1, 1995, and January 15, 2017. A total of 257 met study criteria after the application of exclusion criteria outlined in Supplemental Figure 1 (available online). Pathology slides were reviewed by a pathologist with expertise in MPM to confirm the histological classification. A retrospective chart review was conducted to obtain pre-, peri-, and postoperative data. Clinical stage was obtained from both review of notes in the medical record and radiological data. The pathologic reports were reviewed to obtain TNM data. Both clinical and pathologic staging were updated to reflect the most recent eighth edition of the American Joint Commission on Cancer staging guidelines (12). The operative reports were reviewed to assure correct surgical classification based on the definitions as follows: extrapleural pneumonectomy (13): en bloc resection of the lung and pleura to remove all gross tumor with resection of the diaphragm and/or pericardium as required; radical pleurectomy and decortication: parietal and visceral pleurectomy to remove all gross tumor with resection of the diaphragm and/or pericardium as required; complete pleurectomy and decortication (CPD): parietal and visceral pleurectomy to remove all gross tumor without resection of diaphragm or pericardium. These surgical definitions are widely accepted (14). NAC patients received the standard regimen of pemetrexed and cisplatin. Within our institutional practice, patients were treated with IR prior to the trials that demonstrated survival benefits of pemetrexed and cisplatin. Following the trials, we transitioned to offering patients NAC. To mitigate possible temporal bias, we included the year of surgery in both the multivariable cox models and for propensity score matching.

Duke Cohort: Statistical Analysis

Patients were stratified into two groups based on receipt of NAC or IR after diagnosis. Background characteristics were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum and Pearson χ2 tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The primary outcomes were overall survival (OS) and survival following surgery (postresection survival [RS]), which were estimated using Kaplan-Meier and multivariable Cox proportional hazards models. We defined OS as time from pathologically confirmed diagnosis to death. Death status was determined by chart review and searching the Social Security Death Index Database. RS was defined as the time from curative intent surgery to death. RS was chosen as an alternative measure of survival to mitigate the immortal time bias experienced by patients undergoing NAC. Finally, multivariable cox proportional hazards regression was performed to identify factors independently associated with RS. The proportional hazards assumption for all tests was checked using Schoenfeld residuals.

A one-to-one propensity score–matched analysis was performed using the nearest neighbor algorithm comparing IR patients with NAC patients (15). Both patient and tumor-related variables, including age, sex, Charlson-Deyo comorbidity score (CDCC), tobacco and asbestos exposure, histology, clinical stage, preoperative hemoglobin, preoperative forced expiratory volume 1% predicted, and year of surgery, were used to match patients. Because of the limited number of events in the cohort, the final multivariable Cox model was developed in stages to minimize the degrees of freedom. Univariate analyses tested the effect of numerous variables on RS: age, sex, CDCC score, year of surgery, tobacco use, asbestos exposure, histology, clinical stage, preoperative creatinine, preoperative hemoglobin, preoperative hematocrit, preoperative platelets, pre-operative forced expiratory volume 1% predicted. Only variables that had a statistically significant effect on survival (P < .05) were included in the final model. For all tests, the cutoff point for statistical significance was P less than .05, and all tests were two-sided.

National Cancer Database (NCDB) Cohort: Patient Selection

The aim of the second part of the study was to analyze national data to corroborate the findings from our institutional data. The NCDB is a collaborative initiative of the American Cancer Society and the American College of Surgeons. It is a prospectively maintained registry containing information about approximately 80% of cancers diagnosed in 1500 treatment centers in the United States every year (16). Data are collected by certified, independent tumor registrars. The 2004–2015 NCDB was used to identify patients with American Joint Commission on Cancer eighth edition clinical stage I–IIIB MPM who underwent definitive surgery. Patients with missing survival information were excluded. Only the NCDB codes for definitive surgery were used. While the NCDB does not contain details about surgery specific to mesothelioma, the most common codes for patients undergoing definitive surgery were used including simple/partial removal (30), complete removal (40), debulking (50), and radical surgery (60). Patients were stratified by receipt of NAC.

NCDB Cohort: Statistical Analysis

Primary outcomes were OS and RS, estimated using Kaplan-Meier and multivariable Cox proportional hazards models. The proportional hazards assumption for all tests was checked using Schoenfeld residuals. A one-to-one propensity score–matched analysis was then performed to minimize differences in background characteristics between the two groups (15). Groups were matched on both patient and tumor-related variables including age, sex, race, year of diagnosis, CDCC score, insurance type, treatment location, treatment at an academic center, histology of the tumor, and clinical stage. The final multivariable Cox model was developed in stages to minimize the degrees of freedom. Univariate analyses tested the effect of numerous variables, and only variables that had a statistically significant effect on survival (P < .05) were included in the final model. The cutoff point for statistical significance was P less than .05, and all tests were two-sided.

Additional Analyses

Two additional analyses were performed. First, to test the hypothesis that NAC may be selectively more beneficial in earlier stage patients, we performed a subgroup analysis in only clinical stage I patients using both the Duke registry and the NCDB. Second, because clinical staging may have limited prognostic utility in MPM, we also performed a survival analysis of the original Duke and NCDB cohorts including pathologic rather than clinical stage in the multivariable Cox models. For both of these analyses, the results of a multivariable Cox model using survival from the time of surgery are presented (Supplementary Table 1, available online).

For all the analyses, missing data were handled with complete case analysis, and all statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.5.1 for Mac (Vienna, Austria). The number of total and censored events for every survival analysis is presented in Supplementary Figures 2–9 (available online). A two-sided P value less than or equal to .05 was considered statistically significant. All tests were two-sided.

Results

Duke Cohort: Unadjusted and Adjusted Outcomes

Overall, 257 patients met the inclusion criteria: 127 (49.4%) had IR without NAC and 130 (50.6%) had NAC followed by resection with curative intent. The majority of NAC patients (124; 95.4%) received the most common induction regimen (a pemetrexed and cisplatin combination) for a mean of 3 (1) cycles; two patients (1.5%) received carboplatin and paclitaxel, and the regimen of four (3.1%) patients was unknown. The background characteristics of the patients in each group are summarized in Table 1. Compared with IR patients, NAC patients were more likely to be female, have favorable histology, not have a history of exposure to tobacco and asbestos, and have surgery at a later year. They also had lower preoperative hemoglobin and platelet values.

Table 1.

Background characteristics of Duke patients stratified by primary treatment approach*

| Variable | IR (n = 127) | NAC (n = 130) | P † |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, median (IQR) | 64 (58–70) | 67 (60–72) | .17 |

| Female sex | 10 (8) | 25 (19) | .01 |

| Race | .17 | ||

| White | 120 (94) | 118 (91) | |

| Black | 7 (6) | 7 (5) | |

| Asian | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| Hispanic | 0 | 4 (3) | |

| CDS | .86 | ||

| 0 | 88 (69) | 91 (70) | |

| 1 | 31 (24) | 29 (22) | |

| 2 | 6 (5) | 6 (5) | |

| ≥3 | 2 (2) | 4 (3) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| HTN | 61 (48) | 63 (48) | .99 |

| CHF | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | .50 |

| CAD | 18 (14) | 15 (11) | .66 |

| DM | 16 (13) | 20 (15) | .64 |

| COPD | 10 (8) | 9 (7) | .96 |

| CVA | 2 (2) | 5 (4) | .45 |

| CRI | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | .99 |

| Radiation exposure | 4 (3) | 2 (1) | .44 |

| Tumor characteristics | |||

| Laterality | .75 | ||

| Left | 46 (36) | 51 (39) | |

| Right | 79 (62) | 78 (60) | |

| Bilateral | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| Mediastinal | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| Histologic type | .03 | ||

| Epithelial | 81 (64) | 97 (75) | |

| Biphasic | 38 (30) | 32 (25) | |

| Sarcomatoid | 8 (6) | 1 (1) | |

| Clinical stage | .005 | ||

| IA | 74 (58) | 59 (45) | |

| IB | 22 (17) | 40 (31) | |

| II | 23 (18) | 19 (15) | |

| IIIA | 8 (6) | 5 (4) | |

| IIIB | 0 | 7 (5) | |

| Exposures and risks | |||

| Tobacco exposure | 92 (74) | 80 (62) | .04 |

| Asbestos exposure | 111 (89) | 99 (79) | .04 |

| Year of surgery, median (IQR) | 2005 (2002–2008) | 2013 (2011–2015) | <.001 |

| FEV1% predicted, median (IQR) | 63 (54–75) | 64 (55–74) | .86 |

| Preoperative creatinine, median (IQR), mg/dL | 0.90 (0.80–1.10) | 1.00 (0.80–1.10) | .11 |

| Preoperative hemoglobin, median (IQR), g/dL | 12.9 (11.8–14.2) | 12.3 (11.1–13.5) | .003 |

| Preoperative platelets, median (IQR), 109/L | 329 (271–403) | 260 (210–316) | <.001 |

Unless otherwise specified, the values in each column represent the number of patients with the corresponding percentage in parentheses. CAD = coronary artery disease; CDS = Charlson-Deyo comorbidity index score; CHF = congestive heart failure; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRI = chronic renal insufficiency; CVA = cerebrovascular accident; DM = diabetes mellitus; FEV = forced expiratory volume; HTN = hypertension; IQR = interquartile range; IR = initial resection; NAC = neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

The P value was calculated using the Wilcoxon rank sum and Pearson χ2 tests for continuous and categorical measures, respectively. All tests were two-sided.

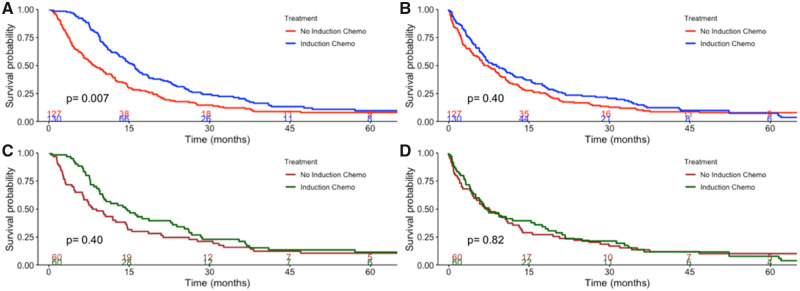

In unadjusted outcomes, IR patients were more likely to have an extrapleural pneumonectomy or a CPD and a higher rate of margin-negative resection compared with NAC patients (Table 2). Pathologic stage, postoperative events, and 30- and 90-day mortality were similar between groups. Although there was a difference in OS in unadjusted analysis (Figure 1A), when analyzing unadjusted RS, there was no difference between the cohorts: median RS was 8.9 months (95% confidence interval [CI] = 6.6 to 12.2) and 7.4 months (95% CI = 5.6 to 9.9) for NAC vs IR, respectively (Figure 1B). In multivariable analysis, NAC was associated with an increased risk of postresection mortality (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.85, 95% CI = 1.21 to 2.83; multivariable Cox P = .005) (Table 3), but not with an increased overall mortality risk (HR = 1.37, 95% CI = 0.90 to 2.09; multivariable Cox P = .14) (Supplemental Table 2, available online).

Table 2.

Unadjusted outcomes for Duke MPM patients stratified by type of primary therapy*

| Variable | IR (n = 127) | NAC (n = 130) | P † |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical operation | <.001 | ||

| EPP | 93 (73) | 48 (37) | |

| RPD | 12 (9) | 66 (51) | |

| CPD | 22 (17) | 16 (12) | |

| Tumor characteristics | |||

| Extent of resection | <.001 | ||

| R0 | 81 (64) | 52 (40) | |

| R1 | 32 (25) | 63 (49) | |

| R2 | 14 (11) | 15 (12) | |

| Pathologic stage | .32 | ||

| IA | 8 (6) | 6 (5) | |

| IB | 57 (46) | 56 (45) | |

| II | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| IIIA | 6 (5) | 13 (10) | |

| IIIB | 50 (40) | 46 (37) | |

| IV | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Unknown | 0 | 2 (2) | |

| Postoperative events | |||

| Length of hospital stay, d | 7 (6–9) | 8 (6-11) | .09 |

| Reoperation, 30 d | 19 (15) | 22 (17) | .80 |

| 30-day event—any | 84 (67) | 77 (60) | .34 |

| 30-day event—major | 37 (29) | 34 (27) | .72 |

| 30-day event—minor | 70 (56) | 66 (52) | .61 |

| Mortality | |||

| Intraoperative | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1.00 |

| 30-day | 12 (9) | 5 (4) | .12 |

| 90-day | 23 (18) | 13 (10) | .09 |

| 90-day <2013 | 22 (18) | 7 (11) | .31 |

| 90-day ≥2013 | 1 (33) | 6 (9) | .70 |

| Complications | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 38 (30) | 26 (20) | .09 |

| Reintubation | 9 (7) | 9 (7) | 1.00 |

| Pneumonia | 6 (5) | 5 (4) | .97 |

| Bacteremia | 1(1) | 2 (2) | 1.00 |

| GI bleed | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | .47 |

| Renal failure | 4 (3) | 7 (5) | .13 |

| Prolonged air leak | 6 (5) | 21 (16) | .01 |

| Empyema | 4 (3) | 7 (5) | .56 |

| Superficial wound infection | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | .98 |

| Deep wound infection | 2 (2) | 9 (7) | .07 |

| Sepsis | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | .99 |

| Chylothorax | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | .25 |

| CVA or stroke | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Vocal cord paralysis | 8 (6) | 9 (7) | 1.00 |

| Esophageal leak | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1.00 |

| Hematoma | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | .63 |

| ARDS | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1.00 |

| Hemorrhage | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | .60 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1.00 |

| Mesh failure | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 1.00 |

| Bowel ischemia | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | .99 |

| Abdominal injury | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1.00 |

| BP fistula | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1.00 |

| Adjuvant therapy | |||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 51 (40) | 7 (5) | NA |

| Adjuvant radiation | 32 (25) | 32 (25) | NA |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation | 19 (15) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Salvage chemotherapy | 17 (24) | 18 (25) | 1.00 |

| Salvage radiation | 9 (14) | 12 (17) | .77 |

Unless otherwise specified, the values in each column represent the number of patients with the corresponding percentage in parentheses. CPD = complete pleurectomy and decortication; EPP = extrapleural pneumonectomy; IQR = interquartile range; IR = initial resection; MPM = malignant pleural mesothelioma; NAC = neoadjuvant chemotherapy; RPD = radical pleurectomy and decortication; R0 = margin-negative resection; R1 = microscopically margin-positive resection; R2 = macroscopically margin-positive resection. Major events: death, gastrointestinal (GI) bleed, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), bacteremia, pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), mesh-failure, perforated viscus, renal failure requiring dialysis, empyema, vocal cord paralysis, sepsis, reoperation to evacuate a hemothorax, hemorrhage, deep wound infection, wound dehiscence, non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, chylothorax, bronchopleural (BP) fistula. Minor events: atrial fibrillation, bronchoscopy, blood transfusion, re-intubation, pleural effusion needing drainage, pneumothorax needing a chest tube, altered mental status, pancreatitis, prolonged air leak, dehydration, deep vein thrombosis, asthma exacerbation, metabolic abnormalities, oxygen requirements, urinary tract infection, ileus, wound cellulitis, acute kidney injury, supraventricular tachycardia.

The P value was calculated using the Wilcoxon rank sum and Pearson χ2 tests for continuous and categorical measures, respectively. All tests were two-sided.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for Duke malignant pleural mesothelioma patients. Kaplan-Meier curves are stratified by receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy demonstrating overall survival (A) and postresection survival (B) in the unmatched Duke cohort and overall survival (C) and postresection survival (D) in the propensity-match Duke cohort. P values represent the two-sided log-rank test. Numbers at risk are provided at the bottom of the graph.

Table 3.

Multivariable Cox regression of factors independently associated with survival computed from surgery in Duke MPM patients

| Variable | Adjusted HR | 95% CI |

Multivariable Cox P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age, per year | 1.02 | 1.00 | 1.04 | .05 |

| Female, reference: male | 0.74 | 0.45 | 1.21 | .23 |

| Charlson-Deyo comorbidity index, reference: 0 | ||||

| 1 | 0.94 | 0.66 | 1.34 | .74 |

| 2 | 1.91 | 0.83 | 4.36 | .13 |

| ≥3 | 0.43 | 0.13 | 1.44 | .17 |

| Histology, reference: epithelial | ||||

| Biphasic | 1.59 | 1.12 | 2.25 | .009 |

| Sarcomatoid | 4.40 | 1.60 | 12.07 | .004 |

| Clinical stage, reference: IA | ||||

| IB | 0.77 | 0.54 | 1.10 | .15 |

| II | 0.84 | 0.55 | 1.27 | .40 |

| IIIA | 1.34 | 0.72 | 2.51 | .36 |

| IIIB | 0.68 | 0.24 | 1.91 | .46 |

| Tobacco exposure | 1.46 | 1.03 | 2.08 | .04 |

| Asbestos exposure | 0.77 | 0.52 | 1.16 | .21 |

| Year of surgery | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.96 | <.001 |

| Preoperative FEV1% predicted | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01 | .58 |

| Preoperative creatinine | 1.45 | 0.75 | 2.82 | .27 |

| Preoperative hemoglobin | 0.89 | 0.82 | 0.97 | .01 |

| Preoperative platelets | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | .001 |

| Preoperative chemotherapy, reference: none | 1.85 | 1.21 | 2.83 | .005 |

All tests were two-sided. CI = confidence interval; FEV = forced expiratory volume; HR = hazard ratio; MPM = malignant pleural mesothelioma.

Duke Cohort: Propensity Match Analysis

After propensity matching, the cohort was composed of 60 pairs of patients. Background characteristics are found in Supplementary Table 3 (available online). There was no statistically significant difference in unadjusted OS (Figure 2C) and RS (Figure 2D) between the NAC and IR cohorts. In multivariable analysis, induction chemotherapy was associated with an increased risk of postresection mortality (HR = 1.62, 95% CI = 1.03 to 2.55; multivariable Cox P = .04) (Table 4), but not with an increased overall mortality risk (HR = 1.16, 95% CI = 0.74 to 1.81, P = .52) (Supplemental Table 4, available online).

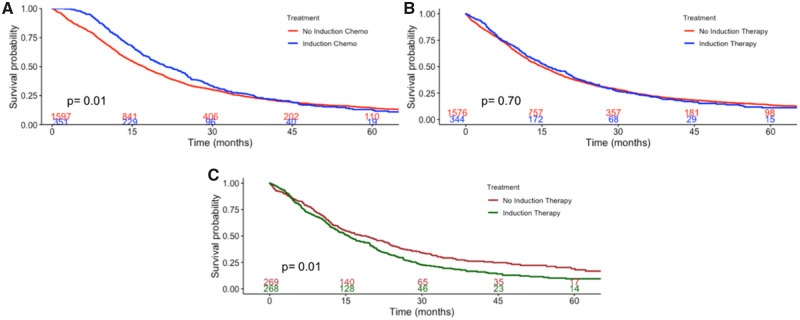

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for National Cancer Database (NCDB) patients. Kaplan-Meier curves are stratified by receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy demonstrating overall survival (A) and postresection survival (B) in the unmatched NCDB cohort and postresection survival (C) in the propensity-match NCDB cohort. P values represent the two-sided log-rank test. Numbers at risk are provided at the bottom of the graph

Table 4.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards model of factors independently associated with survival in propensity score–matched Duke patients, with survival computed from surgery

| Variable | HR | 95% CI |

P * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age, per year | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.05 | .03 |

| Histology, reference: epithelial | ||||

| Biphasic | 2.18 | 1.36 | 3.49 | .001 |

| Sarcomatoid | 4.79 | 1.40 | 16.4 | .01 |

| Clinical stage, reference: IA | ||||

| IB | 0.68 | 0.42 | 1.11 | .12 |

| II | 0.73 | 0.41 | 1.31 | .29 |

| IIIA | 1.38 | 0.67 | 2.83 | .39 |

| IIIB | 0.72 | 0.25 | 2.06 | .54 |

| Year of surgery | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.99 | .03 |

| Preoperative creatinine | 4.23 | 1.54 | 11.7 | .005 |

| Preoperative platelets | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | .001 |

| Preoperative chemotherapy, reference: none | 1.62 | 1.03 | 2.55 | .04 |

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression was performed, and the proportional hazards assumption was checked using Schoenfeld residuals. All tests were two-sided. CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio.

NCDB Cohort

A total of 1949 patients met study criteria: 1597 (81.9%) IR and 352 (18.1%) NAC. The patients in the NAC group were more likely to be younger, have private insurance, be treated at academic centers, and have favorable histology (Table 5). NAC patients experienced a median survival of 21 months (95% CI = 19 to 25) vs 17 months (95% CI = 16 to 18) in the IR group (Figure 2A); however, RS was similar between the two groups (Figure 2B). NAC was associated with an increased risk of postresection mortality (HR = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.02 to 1.39; multivariable Cox P = .02; Table 6), but not with an increased risk of overall mortality (HR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.88 to 1.19; P = .80; Supplementary Table 5, available online).

Table 5.

Preoperative characteristics of NCDB patients with MPM, stratified by receipt of induction therapy*

| Variable | IR (n = 1597) | NAC (n = 352) | P † |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median, y | 69 | 65 | <.001 |

| Sex, female | 404 (25) | 80 (23) | .35 |

| Race | .35 | ||

| Caucasian | 1495 (95) | 333 (96) | |

| Black | 58 (4) | 12 (4) | |

| Other | 25 (2) | 2 (1) | |

| Year of diagnosis, median (IQR) | 2010 (2008–2013) | 2011 (2009–2013) | .003 |

| CDCC score | .05 | ||

| 0 | 1178 (74) | 277 (79) | |

| 1 | 330 (21) | 65 (19) | |

| ≥2 | 89 (6) | 10 (3) | |

| Insurance | <.001 | ||

| Private | 589 (37) | 171 (51) | |

| Government | 967 (61) | 162 (48) | |

| Uninsured | 21 (1) | 4 (1) | |

| Academic | 855 (55) | 255 (74) | <.001 |

| Histology | <.001 | ||

| Epithelioid | 856 (69) | 244 (80) | |

| Biphasic | 233 (19) | 49 (16) | |

| Sarcomatoid | 157 (13) | 12 (4) | |

| Clinical stage | .01 | ||

| IA | 427 (27) | 83 (24) | |

| IB | 669 (42) | 149 (42) | |

| II | 120 (8) | 35 (10) | |

| IIIA | 110 (7) | 39 (11) | |

| IIIB | 271 (17) | 46 (13) | |

| Margin status | <.001 | ||

| R0 | 513 (41) | 150 (54) | |

| R1 | 294 (24) | 70 (25) | |

| R2 | 129 (10) | 19 (7) | |

| Indeterminate | 312 (25) | 41 (15) | |

| Pathologic stage | .29 | ||

| IA | 104 (11) | 21 (8) | |

| IB | 344 (36) | 104 (40) | |

| II | 99 (11) | 24 (9) | |

| IIIA | 163 (17) | 55 (21) | |

| IIIB | 219 (23) | 50 (19) | |

| IV | 17 (2) | 6 (2) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 552 (35) | 48 (14) | <.001 |

Unless otherwise specified, the values in each column represent the number of patients with the corresponding percentage in parentheses. IR = initial resection; MPM = malignant pleural mesothelioma; NAC = neoadjuvant chemotherapy; NCDB = National Cancer Database; R0 = margin-negative resection; R1 = microscopically margin-positive resection; R2 = macroscopically margin-positive resection.

The P value was calculated using the Wilcoxon rank sum and Pearson χ2 tests for continuous and categorical measures, respectively.

Table 6.

Multivariable Cox model of factors independently associated with survival in NCDB patients, with survival computed from surgery

| Predictor | HR | 95% CI |

P * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age, per year | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.03 | <.001 |

| Female sex, reference: male | 0.72 | 0.62 | 0.83 | <.001 |

| Race, reference: white | ||||

| Black | 1.30 | 0.94 | 1.79 | .11 |

| Year of diagnosis | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.99 | .003 |

| Charlson-Deyo comorbidity index, reference: 0 | ||||

| 1 | 0.97 | 0.83 | 1.12 | .66 |

| ≥2 | 1.21 | 0.93 | 1.56 | .15 |

| Insurance, reference: private | ||||

| Government | 1.00 | 0.85 | 1.16 | .96 |

| None | 0.90 | 0.47 | 1.71 | .74 |

| Treatment location, reference: metro | ||||

| Urban | 1.39 | 1.17 | 1.67 | <.001 |

| Rural | 1.13 | 0.70 | 1.81 | .61 |

| Academic center | 0.92 | 0.82 | 1.04 | .19 |

| Histology, reference: epithelial | ||||

| Biphasic | 1.72 | 1.48 | 2.01 | <.001 |

| Sarcomatoid | 2.48 | 2.04 | 3.00 | <.001 |

| Clinical stage, reference: IA | ||||

| IB | 0.97 | 0.84 | 1.13 | .73 |

| II | 1.26 | 1.00 | 1.61 | .05 |

| IIIA | 1.44 | 1.13 | 1.83 | .003 |

| IIIB | 1.62 | 1.35 | 1.95 | <.001 |

| Preoperative chemotherapy, reference: none | ||||

| Preoperative chemotherapy | 1.19 | 1.02 | 1.39 | .02 |

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression was performed, and the proportional hazards assumption was checked using Schoenfeld residuals. All tests were two-sided. CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; NCDB = National Cancer Database.

In a propensity-matched cohort of 269 patient pairs (Supplementary Table 6, available online), NAC patients (median survival = 16 months, 95% CI = 13 to 19) experienced worse RS compared with IR patients (median survival = 19 months, 95% CI = 15 to 23) (log-rank P = .04; Figure 2C). In multivariable analysis, induction chemotherapy (HR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.06 to 1.57; multivariable Cox P = .01) was associated with an increased risk of postresection mortality (Supplementary Table 7, available online) and similar risk of overall mortality (Supplementary Table 8, available online).

Additional Analyses

In the first analysis, patients with exclusively clinical stage I disease were identified. In a multivariable analysis of 195 patients from Duke, there was no difference in RS between patients undergoing IR and NAC, whereas in 1327 NCDB patients, NAC was associated with worse RS compared with IR (Supplementary Table 1, available online). In the second analysis, pathologic rather than clinical stage was included in the multivariable Cox model of the original cohorts because it is more accurate. In a multivariable Cox model, NAC was associated with worse RS compared with IR in both Duke and NCDB patients (Supplementary Table 1, available online).

Discussion

We used institutional and national hospital-based registries to examine the effect of NAC on survival in patients with clinical stage I–III MPM. In both databases, we found that patients receiving NAC experienced similar OS compared with those receiving IR but that patients with NAC had worse RS compared with those receiving IR. Our findings suggest that NAC is not associated with a survival benefit in MPM and that the risks and benefits of NAC should be weighed carefully before offering it to patients with operable disease.

We found that NAC is not associated with improved survival compared with IR. No prospective trials have compared the receipt of NAC with IR. The landmark trials that established the survival benefits of using a combination of pemetrexed and cisplatin compared with cisplatin alone in MPM-enrolled patients who were “not candidates for curative surgery” (4) and who were “not amenable for radical resection” (5). Thus, the trials were composed of 78–79% of patients who had stage III–IV disease and never underwent surgical resection. Nevertheless, the use of pemetrexed and cisplatin has been adopted in both the neoadjuvant and the adjuvant setting in clinical practice, especially because the MARS feasibility trial failed and the SAKK 17/04 trial did not demonstrate a benefit with adjuvant radiation, leaving chemotherapy as the only treatment option with the best level of evidence (17). Sharkey and colleagues (18) compared the use of NAC with adjuvant therapy or as salvage therapy in recurrence. In this single-institution series, only 36 patients had NAC, and compared with those in the adjuvant chemotherapy (AC) and recurrence cohorts, there were no differences in median survival. Another recent observational study by Verma and colleagues (19) used the NCDB to compare OS between NAC and AC and also found that the survival in the cohorts did not differ. In contrast to our study, Verma and colleagues chose to exclude patients with sarcomatoid or node-positive disease. We included these patients because there is no definitive evidence to exclude sarcomatoid MPM from surgical intervention, and node-positive disease is represented in stage IIIB, which, according to the current NCCN guidelines, is potentially a resectable disease. Moreover, the first randomized phase II study of NAC vs IR followed by AC is currently ongoing in Europe and enrolls patients with stage I–IIIB irrespective of the histological subtype (20), further supporting the inclusion of these patients in our analysis. Neither of these studies [Sharkey et al. (18) or Verma et al. (19)] strictly compared NAC with IR but instead compared NAC with AC. In our experience, the majority of the patients who undergo IR do not receive AC; therefore, we elected to perform an intention-to-treat analysis that better represents current clinical practice. Our study is strengthened by the use of two separate databases: an institutional database of a high-volume MPM center with granular data about chemotherapeutic regimens and minimal variability in institutional practice and the NCDB with liberal inclusion criteria to best mimic clinical practice. Moreover, no studies have reported postsurgical survival as a method to account for immortal time bias as we have presented in this body of work. Other studies analyze NAC as part of a trimodality treatment strategy (NAC followed by surgery and adjuvant radiation and/or chemotherapy), and thus the specific effects of NAC are not discernible. The NCCN guidelines recommend either NAC or IR, demonstrating that an accepted treatment paradigm does not exist in resectable MPM. To our knowledge, ours is the largest analysis comparing outcomes of patients undergoing NAC vs IR for MPM, and our findings suggest that the receipt of NAC does not prolong survival in MPM and may in fact be associated with worse survival following surgery.

Our unadjusted and adjusted survival models may appear discrepant. For instance, the unadjusted OS is better for NAC patients compared with IR patients in Figures 1A and 2A by the log-rank test, but OS is similar between the two groups in a multivariable Cox regression (Tables 3 and 6). This is most likely attributable to differences in background characteristics. For instance, Duke patients receiving NAC were more likely than IR patients to be female and have favorable histology, which are good prognostic features. Similarly, NAC patients in the NCDB were more likely to be younger, have fewer comorbidities, be privately insured, be treated at an academic center, and have favorable histology compared with IR patients. After adjustment for these variables in a Cox regression, any OS disparity observed in Kaplan-Meier analysis vanishes. After adjustment for the immortal time bias enjoyed by NAC patients by computing survival from the time of surgery, survival was actually worse for NAC patients compared with IR patients.

There are several possible explanations for the lack of survival benefit observed in patients receiving NAC. First, NAC may not actually decrease tumor burden enough to observe a survival benefit. Studies have documented that only one-third of patients have a radiographic response to NAC (7,21–23). In our institutional cohort, 26 (20%) patients had evidence of response to NAC in restaging studies. As a result, patients who receive surgery delayed by NAC may experience disease progression and, consequently, decreased survival following surgery, which we observed in both our institutional and NCDB cohorts. Another possible explanation is that any benefit obtained from NAC may be negated by its effect on fitness for surgery. We know from feasibility studies that only 70–75% of patients who undergo NAC are able to proceed with surgical resection (17,21). Even among those who complete NAC and proceed with surgery, the effects of lingering myelosuppression on surgical outcomes is unknown. Sharkey and colleagues (18) reported that the cohort of patients who received NAC, compared with AC and recurrence chemotherapy cohorts, had the highest in-hospital mortality (8.3%) and 30-day mortality (5.6%). The NCDB analysis by Verma and colleagues (19) found longer rates of postoperative length of stay and higher 30-day mortality (3.3% vs 0%; P = .20) among those receiving NAC compared with AC. Patients in our institution who underwent NAC had evidence of myelosuppression with lower baseline hemoglobin and platelets compared with patients undergoing IR. This, along with other adverse reactions to induction therapy, may have resulted in worse postsurgical survival in our institutional cohort. Our study has several limitations. As a retrospective cohort analysis, it is limited by selection bias that cannot be entirely adjusted for. We do not know the reasons driving receipt of induction therapy in the NCDB. In our institution, however, mesothelioma has been treated by the same group of oncologists and surgeons throughout the study period, minimizing variability. We were also limited by the variables available in the NCDB, because it does not contain codes specific to surgery for MPM such as radical pleurectomy and decortication and CPD, so we chose codes we believed best represented surgery with curative intent. The NCDB also does not contain information about the chemotherapeutic regimens offered to patients; however, in the case of MPM, there is minimal treatment variation in the neoadjuvant setting, and our study is strengthened by the use of our institutional database, which has detailed information about chemotherapy. Finally, the NCDB does not contain information about the frailty and nutritional status of patients, which may have influenced their receipt of induction therapy.

In this intention-to-treat analysis, we found that OS in clinical stage I–III MPM is similar between those receiving NAC compared with those who have an IR right after diagnosis but that RS is worse within the NAC group. The risks and benefits of NAC should be weighed before offering it to patients with resectable MPM.

Funding

This work received no direct funding. Drs Voigt and Raman were supported by a National Institutes of Health T-32 grant 5T32CA093245 in surgical oncology. Dr Jawitz was supported by a National Institutes of Health T-32 grant 5T32HL069749 in clinical research Dr. Harpole was partially supported by a Department of Defense grant CA160891 for study of mesothelioma.

Notes

The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The authors have no disclosures.

The American College of Surgeons is in a Business Associate Agreement that includes a data use agreement with each of its Commission on Cancer–accredited hospitals. The data used in the study are derived from a deidentified NCDB file. The American College of Surgeons and the Commission on Cancer have not verified and are not responsible for the analytic or statistical methodology used or the conclusions drawn from these data by the investigators.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Hountis P, Chounti M, Matthaios D, Romanidis K, Moraitis S. Surgical treatment for malignant pleural mesothelioma: extrapleural pneumonectomy, pleurectomy/decortication or extended pleurectomy? J Buon. 2015;20(2):376–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cao C, Tian D, Park J, Allan J, Pataky KA, Yan TD. A systematic review and meta-analysis of surgical treatments for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Lung Cancer. 2014;83(2):240–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rusch V, Baldini EH, Bueno R, et al. The role of surgical cytoreduction in the treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma: meeting summary of the International Mesothelioma Interest Group Congress, September 11-14, 2012, Boston, Mass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145(4):909–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vogelzang NJ, Rusthoven JJ, Symanowski J, et al. Phase III study of pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(14):2636–2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Van Meerbeeck JP, Gaafar R, Manegold C, et al. Randomized phase III study of cisplatin with or without raltitrexed in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: an intergroup study of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Lung Cancer Group and the National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(28):6881–6889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Treasure T, Lang-Lazdunski L, Waller D, et al. Extra-pleural pneumonectomy versus no extra-pleural pneumonectomy for patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: clinical outcomes of the Mesothelioma and Radical Surgery (MARS) randomised feasibility study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(8):763–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stahel R, Weder W. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Lung Cancer. 2005;49 (suppl 1):S69–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shohdy K, Abdel-Rahman O. The timing of chemotherapy in the management plan for medically operable early-stage malignant pleural mesothelioma. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2019;13(6):579–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bolukbas S, Eberlein M, Fisseler-Eckhoff A, Schirren J. Radical pleurectomy and chemoradiation for malignant pleural mesothelioma: the outcome of incomplete resections. Lung Cancer. 2013;81(2):241–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lau B, Kumar S, Yan T, et al. Pathological complete response in malignant pleural mesothelioma patients following induction chemotherapy: predictive factors and outcomes. Lung Cancer. 2017;111:75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Network NCC. Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (Version 2); 2018. https://oncolife.com.ua/doc/nccn/Malignant_Pleural_Mesothelioma.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2019.

- 12. Berzenji L, Van Schil PE, Carp L. The eighth TNM classification for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2018;7(5):543–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Federico R, Adolfo F, Giuseppe M, et al. Phase II trial of neoadjuvant pemetrexed plus cisplatin followed by surgery and radiation in the treatment of pleural mesothelioma. BMC Cancer. 2013;13(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cao C, Akhunji Z, Fu B, et al. Surgical management of malignant pleural mesothelioma: an update of clinical evidence. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;27(1):6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stuart EA, King G, Imai K, Ho MatchIt D. Nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J Stat Soft. 2011;42(8):1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Ko CY. The National Cancer Data Base: a powerful initiative to improve cancer care in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(3):683–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stahel RA, Riesterer O, Xyrafas A, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and extrapleural pneumonectomy of malignant pleural mesothelioma with or without hemithoracic radiotherapy (SAKK 17/04): a randomised, international, multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(16):1651–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sharkey AJ, O’Byrne KJ, Nakas A, Tenconi S, Fennell DA, Waller DA. How does the timing of chemotherapy affect outcome following radical surgery for malignant pleural mesothelioma? Lung Cancer. 2016;100:5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Verma V, Ahern CA, Berlind CG, et al. Treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma with chemotherapy preceding versus after surgical resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;157(2):758–766.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Raskin J, Surmont V, Cornelissen R, Baas P, van Schil PEY, van Meerbeeck JP. A randomized phase II study of pleurectomy/decortication preceded or followed by (neo-)adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with early stage malignant pleural mesothelioma (EORTC 1205). Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2018;7(5):593–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hasegawa S, Okada M, Tanaka F, et al. Trimodality strategy for treating malignant pleural mesothelioma: results of a feasibility study of induction pemetrexed plus cisplatin followed by extrapleural pneumonectomy and postoperative hemithoracic radiation (Japan Mesothelioma Interest Group 0601 Trial). Int J Clin Oncol. 2016;21(3):523–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Donahoe L, Cho J, de Perrot M. Novel induction therapies for pleural mesothelioma. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;26(3):192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pasello G, Ceresoli GL, Favaretto A. An overview of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the multimodality treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39(1):10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.