KEY POINTS

Federal–provincial and territorial cost-sharing arrangements that support publicly financed health services in Canada have evolved over the course of more than 60 years and remain contentious today.

The fraught history of cost-sharing illustrates why the federal and provincial and territorial governments have divergent views on a fair deal to support Canada’s health care systems.

Examination of the benchmarks used historically for cost sharing shows that there is a ~$20 billion variance in the level of current federal support depending on whether credit is given for tax points transferred in 1977, and on a cash-only basis, discrepancies against benchmarks range from ~$15 billion in surplus to a ~$23 billion deficit.

These discrepancies and ongoing federal–provincial and territorial disputes about cost sharing pose challenges to the jurisdictional collaboration that is essential for expansion of public coverage and successful reforms in health care.

A rational process to determine a fair deal for interjurisdictional funding of Canada’s publicly financed health services is urgently needed.

As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic continues in Canada and financial pressures mount on all levels of government, the federal–provincial/territorial cost-sharing framework for universal publicly financed coverage of physician and hospital services — commonly referred to as Medicare — has once again become a point of contention. In September 2020, just days before a federal Speech from the Throne, Canada’s provincial and territorial premiers called for the federal government to become “a full funding partner” in health care spending, raising its contribution to provincial and territorial health spending from 22% to 35%, an increase of $28 billion per annum.1 Yet, to the expressed disappointment of the premiers,2 the Throne Speech offered no increases in federal funding for health. Instead it reiterated the Government of Canada’s previous commitment to “a national, universal pharmacare program” and set out some steps toward that goal.

Although Medicare remains one of the social programs that Canadians value most highly, its stability, and any potential expansion of Medicare services, such as pharmacare, depends on a robust federal–provincial/territorial cost-sharing framework. Yet, the conflicting perspectives of different levels of government pose major challenges to any expansion of public coverage or pursuit of national health care reforms.

We review the history of federal–provincial/territorial bargaining that led to the current Medicare system and consider what constitutes a fair deal in the current climate, drawing on a variety of print and online sources (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.200143/tab-related-content) as well as the firsthand observations of 2 of the authors starting in the 1980s.

What is the history of Medicare bargaining in Canada?

Nothing in the 1867 Canadian constitution anticipated national health insurance programs. The constitution instead assigns authority for oversight and delivery of health care services to provinces and territories. Hence, provinces moved at different speeds to implement public coverage of health care, with Saskatchewan pioneering universal hospital insurance in 1947 and universal medical services insurance in 1962. This constitutional reality means that Canada has 13 somewhat distinctive provincial or territorial health care systems. Those systems have much in common, however, given shared fiscal and legislative DNA arising from a series of agreements that, since the late 1950s, have set out terms and conditions for sharing of specified costs between the Government of Canada and provinces and territories.

Full cost sharing (1957–1976)

The Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act, which received Royal Assent in April 1957,3 offered funding to participating provinces at roughly 50% of the per capita cost of eligible services delivered at general hospitals. Cost sharing initially meant that richer provinces received more funding because of higher per-capita outlays on hospital care. This was mitigated by using national average spending levels as a benchmark for half the allocation.

Sparked by the 1964 report of a Royal Commission chaired by Justice Emmett Hall, in 1966 the Government of Canada passed the Medical Care Act. This Act offered to cover 50% of the national average per capita cost of all insured medical services, net of plan administration costs and patient premiums.4 These 2 federal initiatives underpin Canada’s national Medicare plan.

In 1976/77, the last year for which funding for these 2 Acts is recorded distinctly in the Public Accounts of Canada, the coverage was 48% of hospital spending and 49% of physician spending.5 To this point, the federal government had honoured its 50:50 commitment.

The new deal (1976–1995)

As early as 1970, the federal government began weighing how it might limit increases in its share of health spending to the rate of growth of gross national product (GNP). (Gross national product adds net income receipts from abroad to gross domestic product [GDP], which was later adopted as the preferred national benchmark for cost sharing.) At a First Ministers Meeting in 1976, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau proposed replacing 50:50 cost-sharing with a new regime. One-half of the 1975/76 payments for 3 cost-shared programs (Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act, Medical Care Act and postsecondary education) would be paid as a block grant, escalated annually in accordance with a 3-year moving average of nominal per capita GNP growth. The other half would be offset by reducing specified federal taxes, allowing provinces to take up those revenues without any immediate changes to taxes paid by individuals and businesses.6,7

Several provinces worried that moving from 50:50 cost sharing to block grants would expose them to unilateral federal cuts. Others agreed with federal negotiators who argued that block grants and tax points would allow provinces to reduce spending on medical services and general hospitals in favour of more cost-effective services such as home care. Ultimately, the provinces and territories agreed to a slightly more generous version of the federal proposal, embodied in the Established Programs Financing Act that took effect in April 1977.8

In 1979, Justice Emmett Hall was asked by the Government of Canada to revisit his 1964 report.9 His findings led to the 1984 Canada Health Act, consolidating earlier legislation and, for the first time, giving the federal government authority to make dollar-for-dollar deductions of transfers to provinces that allowed user charges for publicly insured services.

Six federal budgets between 1985 and 1995 variously scaled back the GNP escalator on combined health and social cash transfers or completely froze payments. In a 1991 background paper, Alistair Thomson calculated that health transfers cumulatively reduced by $30 billion from 1986/87 to 1995/96.10 Further reductions through to 1998/99 trimmed another $11.2 billion relative to the 1977 agreed terms.11

Partial restitution and health accords (1996–2006)

As federal finances improved, the 1999 federal budget provided a base increase in combined health and social cash transfers of $11.5 billion over 5 years.12 Provincial and territorial officials called for more investment based on previous benchmarks and offered a new argument after being introduced to the concept of a vertical fiscal imbalance by economist G.C. Ruggeri in August 2000 (Appendix 2, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.200143/tab-related-content). Ruggeri defined vertical imbalance as arising when subnational governments face spending pressures that outstrip their revenue-raising capacity while the national government produces surpluses over time.13 This concern has been a core element of premiers’ arguments for more federal funding ever since.

With a November 2000 election looming, the premiers’ complaints could not be ignored and a First Ministers Meeting led to the first Health Accord. The 2000 accord raised the combined health and social transfer from $15.5 billion in 2000/01 to $21 billion by 2005/06, along with one-time funding for medical equipment, health information technology and primary care reform.14

The re-elected government convened the Romanow Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada in April 2001. Among other findings, the commission observed that federal cash transfers in 2001/02 covered only 18.7% of provinces’ and territories’ expenditures on hospital and physician services. Given the Established Programs Financing Act agreement, the commission recommended that “at a minimum” the federal cash transfer should be raised to 25% of those provincial and territorial costs.15

First ministers reached a second Health Accord in February 2003,16 after which a separate Canada Health Transfer was reinstituted in the federal budget, augmenting health funding by $34.8 billion over the next 5 years. However, most new funding was for short-term boosts to primary and home care. Only $9.5 billion was dedicated to base increases in the Canada Health Transfer.17

The Romanow Commission had tied the 25% federal cash contribution to only medical and hospital services. However, the provinces and territories announced in July 2003 that the recent federal budget had only raised federal funding from 14% of total provincial and territorial health spending to 16%.18

At another First Ministers’ Meeting in the summer of 2004 that focused on health, the parties agreed on a third 10-year accord that Prime Minister Paul Martin called “the fix for a generation.” The new spending totaled $41.3 billion. Growth in the Canada Health Transfer accounted for $35.3 billion, arising from initial one-time increases spread over 2 years, and then application of a 6% annual escalator to the new base. The further increase was through termlimited funds for medical equipment and reductions in wait times.19

New governments, old issues (2006–2018)

Starting in the 1950s, the Government of Canada had repeatedly leveraged its fiscal capacity to catalyze adoption of national social programs by provinces and territories. A more cautious approach to fiscal federalism ensued when a Conservative government took office in 2006. However, seeking re-election in 2011, Prime Minister Stephen Harper pledged to negotiate a fourth Health Accord.20 No negotiations ensued. Instead, at a December 2011 gathering of federal, provincial and territorial finance ministers, Federal Minister James Flaherty announced that when the 2004 accord expired in 2014, the Canada Health Transfer escalator would remain at 6% until 2017 and then grow for the next decade at the higher of 3% per annum or the 3-year moving average of nominal GDP growth %.21 A provincial/territorial working group estimated that these new rules would reduce federal outlays for health by a cumulative $36 billion as compared to those expected had the 6% escalator remained in place from 2014/15 through 2023/24.22

In July 2015 premiers again called on the federal government to increase the Canada Health Transfer envelope to cover 25% of all health spending.23 The Liberals during their campaigning soon after, criticized the Harper government for its action on health financing and promised, if elected, to negotiate a new Health Accord with provincial and territorial governments,24 a commitment reaffirmed in the Liberal Speech from the Throne after they successfully won a majority in the October 2015 federal election.25 Yet again, no health summit occurred. The 2017 federal budget reaffirmed the drop in the Canada Health Transfer escalator set by the Harper Government while providing term-limited funding of $11 billion over 10 years for home care and mental health initiatives.26

The current provincial position (2019–2020)

In July 2019, with pharmacare on the federal agenda (Final Report of the Advisory Council on the Implementation of National Pharmacare, available at www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/about-health-canada/public-engagement/external-advisory-bodies/implementation-national-pharmacare/final-report.html), premiers emphasized the need for long-term coverage of escalation of drug costs in any national drug coverage plan. They also highlighted work done by the Office of the Parlimentary Budget Officer and Conference Board of Canada that supported their ongoing concerns about an imbalance of revenues and responsibilities between the Government of Canada and the provinces (Appendix 2). In response, the premiers called for a new Canada Health Transfer annual escalator of 5.2% instead of the prevailing 3%.27 In 2020, with the arrival of COVID-19, provincial and territorial premiers began to apply more pressure on the federal government with the goal of raising federal contributions from a 22% to 35% share of the provincial and territorial annual outlay.1

What does this mean for pan-Canadian health care initiatives?

Federal attempts to contain spending on health

Cost sharing on a proportionate basis puts the national partner at risk if the subnational partners fail to control spending. Within 2 years of extending its promise of 50:50 cost sharing from general hospitals to physician services, the Government of Canada began seeking ways to contain its financial exposure. Indeed, in fiscal year 1974 alone, outlays for the 2 cost-shared health programs rose by almost 20%. From 1999 to 2009, provincial and territorial spending outstripped generous increases in the Government of Canada’s cash transfer, thereby driving down the federal share.

The advent of block grants in 1977/78, with health transfers variously bundled or uncoupled from social transfers, ended proportional cost sharing and mitigated a perverse incentive for provinces to invest preferentially in physican and hospital services as the only cost-shared services. However, it also opened the door for the federal government to unilaterally change the block-grant escalator and otherwise contain its payments — as happened repeatedly in the 1980s and 1990s, and again in 2011. Furthermore, legal redress proved impossible: in 1991, when the province of British Columbia challenged unilateral federal changes to health and social transfers, federal authority was upheld by the Supreme Court of Canada.28

Piecemeal provincial reforms

Provinces and territories rightly assert their constitutional authority over delivery of health services. That authority in turn means that they bear primary responsibility for the state of these systems, even if their efforts at times were undermined by federal decisions that arbitrarily cut transfers in repeated abrogation of the terms of the original Established Programs Financing Act legislation. When compared with peer nations on many performance measures, such as waiting times for a wide variety of services, Canadian health systems are not strong performers.29,30 Provincial and federal reviews have observed that Canada’s provincial and territorial health care systems are weakly integrated with a fragmented budgetary architecture that is a recognized impediment to efficiency, quality and innovation — and a source of frustration to those working in them.30

Why do cash transfers dominate negotiations?

By assigning revenue directly to provinces from the federal component of joint federal–provincial/territorial tax returns, the Government of Canada sought to create a permanent provincially or territorially controlled endowment for cost-shared programs in 1977. However, tax points are opaque compared with annual cash transfers.

Indeed, by 2006, the premiers’ Advisory Panel on the Fiscal Imbalance rejected all federal claims about the ongoing value of the 1977 tax points, claiming they were now simply a part of provincial tax regimes: “If there is a political debate within a province about excessively high tax levels, those tax points are simply part of the overall tax burden the province’s residents are shouldering. The political responsibility of imposing these taxes rests unequivocally with the provincial governments, not the Government of Canada.”31 Predictably, finance officials continued to impute an overall value to that contribution. But imputing fair values for any given province is challenging because federal and provincial and territorial taxation policies and revenue bases have shifted dramatically over the course of 4 decades. Today, federal officials seldom invoke this element of the cornerstone 1977 cost-sharing agreement.

What is a fair deal?

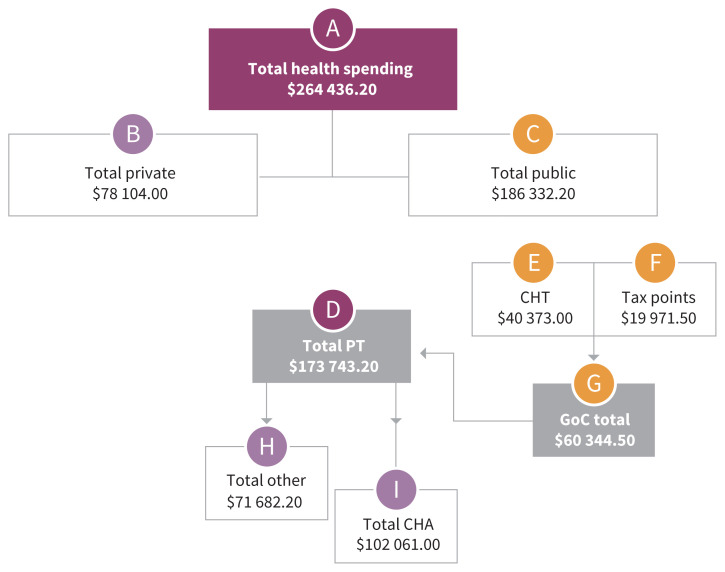

Figure 1 shows some of the relevant flows of federal and provincial health care funds projected for 2019/20 (see also Appendix 1), and Table 1 examines cost-sharing options and benchmarks.

Figure 1:

Schematic of current cost sharing relevant to Medicare in Canada, projected for 2019/20. Note: CHA = Canada Health Act, CHT = Canada Health Transfer, GoC = Government of Canada, PT = provincial/territorial. All values are in millions of Canadian dollars. (A) Total public and private health spending in calendar year 2019. (B and C) Breakdown of A into private and public sector shares for calendar year 2019. (D) Total provincial and territorial spending on health care. (E) The CHT is the annual federal cash transfer to provinces and territories. It is calculated only for fiscal years (2019/20), thus all totals for (D) to (I) are on that basis. Differences are minimal (e.g., the calendar/fiscal ratio is above 99% where both numbers are available). (F) Imputed value in 2019/20 dollars of tax points first transferred to provinces and territories in 1977, based on Department of Finance Canada escalators of federal tax points transferred to provinces and territories in 1977. (G) Combines the components in (E) and (F), showing the total support provided by the GoC. (H) Provincial and territorial spending on services not covered by the conditions set out in the 1985 CHA. (I) Services covered by the 1985 CHA, specifically physicians’ services and general hospital care with related diagnostic services.

Table 1:

Benchmarking the federal share of provincial and territorial publicly financed health spending (all values in millions of Canadian dollars)

| Measure (value) | Benchmark | Benchmark value, $ | Federal surplus (shortfall), $ |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHT ($40 373.00) | 25% of total PT health spending | 43 435.80 | (3062.80) |

| 25% of PT health spending on physician and general hospital services | 25 515.30 | 14 857.70 | |

| 37% of total PT health spending* | 64 285.00 | (23 912.00) | |

| CHT + tax points ($60 344.50) | 37% of total PT health spending* | 64 285.00 | (3940.50) |

Note: CHT = Canada Health Transfer, PT = provincial/territorial.

At the time of the Established Programs Financing Act arrangement, physician and hospital services accounted for 74%–75% of total PT spending on health care. The expectation was that ceded federal tax points and a Government of Canada cash transfer that together represented a 50% share of that amount would escalate in proportion to overall economic growth and be available for funding all health services, hence the 37% benchmark.

As noted by the Romanow Commission, the Established Programs Financing Act defined cost-sharing cash transfers scaled initially to be 25% of average provincial spending for physician and general hospital services. As Table 1, row 2 shows, this benchmark represents a substantial surplus in favour of the federal government. However, it also makes little sense, as the foundational cost-sharing arrangement was presented and accepted specifically to untether spending from a benchmark based on medical and hospital costs.

Since 2003 provinces and territories have used a benchmark of 25% of total health spending for cash transfers. As shown in Table 1 row 1, this leads to a shortfall in Government of Canada spending of $3062.80 million per annum, which is also questionable, as the initial agreement involved both tax points and a steadily escalating cash transfer.

At no point has the federal government ever proposed to cover 50% of all provincial and territorial health spending. An alternative baseline is its commitment to provide over time a block sum scaled to 50% of the proportion of provincial and territorial spending attributable to hospitals and physicians as of 1977/78 when the Established Programs Financing Act was struck (which at the time represented 74%–75% of total health spending). This historic benchmark would thus see the Government of Canada covering no less than 37% of all provincial and territorial health spending.

If the historic benchmark is applied and federal coverage of 37% of provincial and territorial health spending is deemed a fair deal, the key question then becomes how tax points are tallied. If, as the provinces and territories have argued, tax points are immaterial to current negotiations, the federal shortfall moves toward the levels claimed by the premiers in September 2020 as shown in Table 1, row 3. If, however, an escalating value is imputed to tax points ceded by the federal government in 1977, the deficit is much smaller at $3940.50 million per annum (Table 1, row 4).

Conclusion

The Canadian federal–provincial/territorial relationship in health care is coloured by a complex, decades-long history of mutual frustrations and disappointments. Federal governments of all political stripes have repeatedly abrogated the 1977 bargain, while Canada’s provinces and territories have largely failed to effect fundamental reforms that might contain long-term cost escalation and strongly enhance value-for-money in publicly financed health care. This history, along with persisting multibillion dollar disagreements about numerators and denominators for cost-sharing calculations, not only explains recurrent tensions. It also creates a difficult backdrop for new cooperative initiatives that involve large outlays of public funds and new cost-sharing arrangements, such as universal Pharmacare, improved support for long-term care or expanded coverage of mental health services. Absent a process to agree on rational benchmarks for fair inter-jurisdictional cost sharing, prospects for overdue changes in the financing, organization and scope of Canada’s publicly financed health care services will be bleak.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All of the authors contributed to the conception of the article, drafted the work, revised it critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work and its accuracy or integrity.

Funding: C. David Naylor and Andrew Boozary are supported by the University of Toronto. Andrew Boozary is supported by the University Health Network, Toronto. Owen Adams is supported by the Canadian Medical Association, Ottawa. There were no specific sponsors for this work.

References

- 1.Canada’s Premiers outline priorities [news release]. Ottawa: Council of the Federation Secretariat; 2020. Sept. 18 Available: www.canadaspremiers.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Sept_18_COF_Communique_final.pdf (accessed 2020 Sept. 28). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canada’s Premiers reiterate priorities [news release]. Ottawa: Council of the Federation Secretariat; 2020. Sept. 24 Available: www.canadaspremiers.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Sept_24_COF_Communique_fnl.pdf (accessed 2020 Sept. 28). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act. SC 1957, c 28.

- 4.Canada. Medical Care Act. SC 1966–67, c 64.

- 5.Goyer J. Public accounts of Canada 1977. Volume I: Summary report and financial statements. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor MG. Insuring national medical care: the Canadian experience. Chapel Hill (NC): University of North Carolina Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Special Committee on the Federal–Provincial Fiscal Arrangements. Fiscal federalism in Canada: report of the Parliamentary Task Force on Federal–Provincial Fiscal Arrangements. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Federal–Provincial Fiscal Arrangements and Established Programs Financing Act, 1977. S.C. 1976–77, c. 10, s. 27(8).

- 9.Hall EM. Canada’s national-provincial health program for the 1980’s: a commitment for renewal. Ottawa: Health and Welfare Canada; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomson A. Federal support for health care: a background paper. Ottawa: Health Action Lobby; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Historical transfer tables: 1980 to present. Ottawa: Department of Finance Canada; 2017, modified 2020 Jan. 19. Available: https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/4eee1558-45b7-4484-9336-e692897d393f#wb-auto-6 (accessed 2020 Jan. 11). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Finance Canada. The budget plan 1999: including supplementary information and notices of ways and means motions — building today for a better tomorrow. Ottawa: Finance Canada Distribution Centre; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruggeri GC. A federation out of balance. In: Proceedings of the 41st Annual Premiers’ Conference; 2000 Aug. 9–11; Winnipeg: Lombard Hotel. Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat. [Google Scholar]

- 14.First Ministers’ meeting communiqué on health [news release]. Ottawa: Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat; 2000. Sept. 11 Available: https://scics.ca/en/product-produit/news-release-first-ministers-meeting-communique-on-health/ (accessed 2020 Jan. 14). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romanow RJ. Building on values: the future of health care in Canada. Ottawa: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.2003 First Ministers’ Accord on Health Care Renewal. Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat. Ottawa: Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat; 2003. Available: www.scics.gc.ca/CMFiles/800039004_e1GTC-352011-6102.pdf (accessed 2020 Jan. 11). [Google Scholar]

- 17.The budget plan 2003. Ottawa: Department of Finance Canada; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Health care remains Premiers’ number one priority. In: Proceedings of the 44th Premiers’ Conference; 2003 July 9–11; Charlottetown. Ottawa: Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat; Available: https://scics.ca/en/product-produit/news-release-health-care-remains-premiers%E2%80%99-number-one-priority/ (accessed 2020 Jan. 11). [Google Scholar]

- 19.A 10-year plan to strengthen health care. Ottawa: Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat; Available: https://scics.ca/wp-content/uploads/CMFiles/800042005_e1JXB-342011-6611.pdf (accessed 2020 Jan. 11). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Here for Canada: Stephen Harper’s low-tax plan for job and economic growth. Ottawa: Conservative Party of Canada; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Department of Finance Canada. Harper government announces major new investment in health care. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada; 2011. Available: http://webarchive.bac-lac.gc.ca:8080/wayback/20140806102655/http://www.fin.gc.ca/n11/11-141-eng.asp (accessed 2020 Jan. 11). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Report of the Council of the Federation Working Group on Fiscal Arrangements: assessment of the fiscal impact of the current federal fiscal proposals. Ottawa: Council of the Federation Secreteriat; 2012. Available: www.canadaspremiers.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/cof_working_group_on_fiscal_arrangements_report_and_appendices_july.pdf (accessed 2020 Jan. 11). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Providing services for an aging population. Ottawa: Council of the Federation Secreteriat; 2015. Available: https://canadaspremiers.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/aging_final.pdf (accessed 2020 Jan. 11). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Real change: a new plan for a strong middle class. Ottawa: Liberal Party of Canada; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Debate of the Senate. 42nd Parliament, 1st sess, 2015. December 4 Available: https://sencanada.ca/en/Content/Sen/chamber/421/debates/002db_2015-12-04-e#1 (accessed 2020 Jan. 11).

- 26.Morneau B. Budget 2017 — Building a strong middle class. Ottawa: Department of Finance Canada; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Premiers committed to healthcare sustainability, call on federal government to be full, partner. Ottawa: Council of the Federation Secreteriat; 2019. Available: www.canadaspremiers.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Health_Sustainability_and_Mental_Health_July11_FINAL.pdf (accessed 2020 Jan. 11). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reference Re Canada Assistance Plan (B.C.) [1991] 2 SCR 525. Ottawa: Supreme Court of Canada; 1991. Available: https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/781/index.do (accessed 2020 Jan. 11). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider EC, Sarnak DO, Squires D, et al. Mirror, Mirror 2017: international comparison reflects flaws and opportunities for better U.S. health care. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 2017. Available: www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_fund_report_2017_jul_schneider_mirror_mirror_2017.pdf (accessed 2020 Mar. 9). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Unleashing innovation: excellent healthcare for Canada — Report of the Advisory Panel on Healthcare Innovation. Ottawa: Health Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Council of the Federation Advisory Panel on Fiscal Imbalance. Reconciling the irreconcilable: addressing Canada’s fiscal imbalance. Ottawa: Council of the Federation Secretariat; 2006. Available: www.canadaspremiers.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/report_fiscalim_mar3106.pdf (accessed 2020 Jan. 14). [Google Scholar]