Abstract

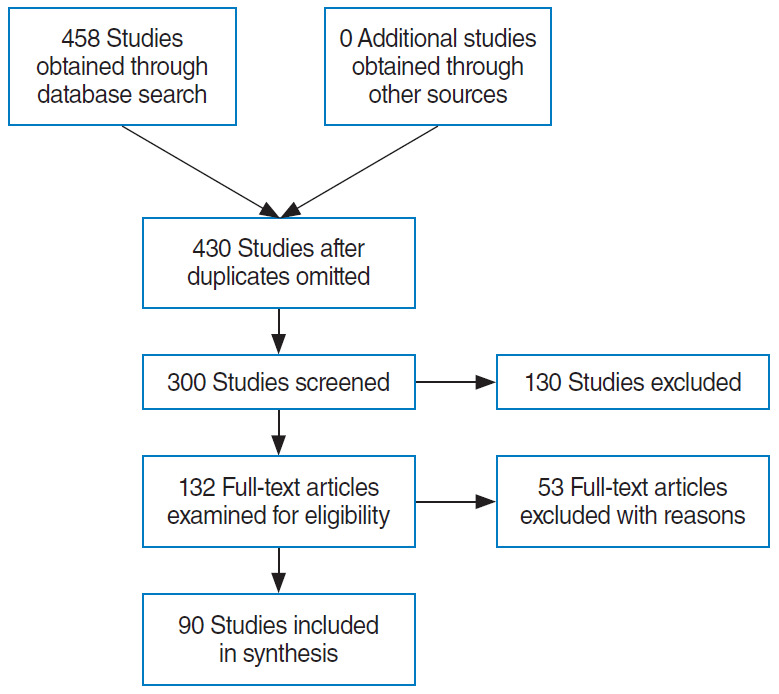

This study presents an up-to-date survey of the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in the field of otorhinolaryngology, considering opportunities, research challenges, and research directions. We searched PubMed, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Embase, and the Web of Science. We initially retrieved 458 articles. The exclusion of non-English publications and duplicates yielded a total of 90 remaining studies. These 90 studies were divided into those analyzing medical images, voice, medical devices, and clinical diagnoses and treatments. Most studies (42.2%, 38/90) used AI for image-based analysis, followed by clinical diagnoses and treatments (24 studies). Each of the remaining two subcategories included 14 studies. Machine learning and deep learning have been extensively applied in the field of otorhinolaryngology. However, the performance of AI models varies and research challenges remain.

Keywords: Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, Deep Learning, Otorhinolaryngology

INTRODUCTION

Artificial intelligence (AI) refers to the ability of machines to mimic human intelligence without explicit programming; AI can solve tasks that require complex decision-making [1,2]. Recent advances in computing power and big data handling have encouraged the use of AI to aid or substitute for conventional approaches. The results of AI applications are promising, and have attracted the attention of researchers and practitioners. In 2015, some AI applications began to outperform human intelligence: ResNet performed better than humans in the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Competition 2015 [3], and AlphaGo became the first computer Go program to beat a professional Go player in October 2015 [4]. Such technical advances have promising implications for medical applications, particularly because the amount of medical data is doubling every 73 days in 2020 [5]. As such, it is expected that AI will revolutionize healthcare because of its ability to handle data at a massive scale. Currently, AI-based medical platforms support diagnosis, treatment, and prognostic assessments at many healthcare facilities worldwide. The applications of AI include drug development, patient monitoring, and personalized treatment. For example, IBM Watson is a pioneering AI-based medical technology platform used by over 230 organizations worldwide. IBM Watson has consistently outperformed humans in several case studies. In 2016, IBM Watson diagnosed a rare form of leukemia by referring to a dataset of 20 million oncology records [6]. It is clear that the use of AI will fundamentally revolutionize medicine. Frost and Sullivan (a research company) forecast that AI will boost medical outcomes by 30%–40% and reduce treatment costs by up to 50%. The AI healthcare market is expected to attain a value of USD 31.3 billion by 2025 [7].

Otorhinolaryngologists use many instruments to examine patients. Since the early 1990s, AI has been increasingly used to analyze radiological and pathological images, audiometric data, and cochlear implant (CI). Performance [8-10]. As various methods of AI analysis have been developed and refined, the practical scope of AI in the otorhinolaryngological field has been broadened (e.g., virtual reality technology [11-13]). Therefore, it is essential for otorhinolaryngologists to understand the capabilities and limitations of AI. In addition, a data-driven approach to healthcare requires clinicians to ask the right questions and to fit well into interdisciplinary teams [8].

Herein, we review the basics of AI, its current status, and future opportunities for AI in the field of otorhinolaryngology. We seek to answer two questions: “Which areas of otorhinolaryngology have benefited most from AI?” and “ What does the future hold?”

MACHINE LEARNING AND DEEP LEARNING

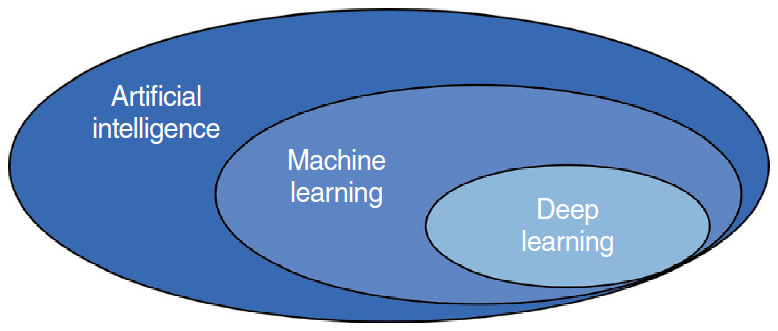

AI has fascinated medical researchers and practitioners since the advent of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) (two forms of AI) in 1990 and 2010, respectively. A flowchart of the literature search and study selection is presented in Fig. 1. Importantly, AI, ML, and DL overlap (Fig. 2). There is no single definition of AI; its purpose is to automate tasks that generally require the application of human intelligence [14]. Such tasks include object detection and recognition, visual understanding, and decision-making. Generally, AI incorporates both ML and DL, as well as many other techniques that are difficult to map onto recognized learning paradigms. ML is a data-driven technique that blends computer science with statistics, optimization, and probability [15]. An ML algorithm requires (1) input data, (2) examples of correct predictions, and (3) a means of validating algorithm performance. ML uses input data to build a model (i.e., a pattern) that allows humans to draw inferences [16,17]. DL is a subfield of ML, in which tens or hundreds of representative layers are learned with the aid of neural networks. A neural network is a learning structure that features several neurons; when combined with an activation function, a neural network delivers non-linear predictions. Unlike traditional ML algorithms, which typically only extract features, DL processes raw data to define the representations required for classification [18]. DL has been incorporated in many AI applications, including those for medical purposes [19]. The applications of DL thus far include image classification, speech recognition, autonomous driving, and text-to-speech conversion; in these domains, the performance of DL is at least as good as that of humans. Given the significant roles played by ML and DL in the medical field, clinicians must understand both the advantages and limitations of data-driven analytical tools.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the literature search and study selection.

Fig. 2.

Interconnections between artificial intelligence, machine learning, and deep learning.

AI IN THE FIELD OF OTORHINOLARYNGOLOGY

AI aids medical image-based analysis

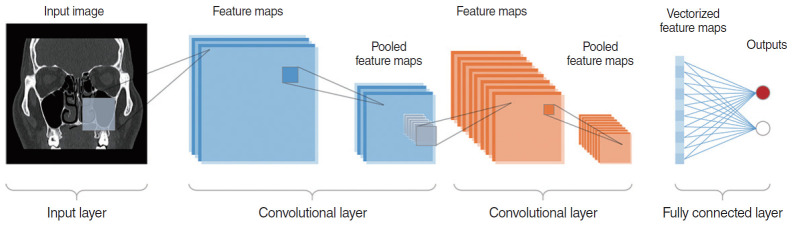

Medical imaging yields a visual representation of an internal bodily region to facilitate analysis and treatment. Ear, nose, and throat-related diseases are imaged in various manners. Table 1 summarizes the 38 studies that used AI to assist medical image-based analysis in clinical otorhinolaryngology. Nine studies (23.7%) addressed hyperspectral imaging, nine studies (23.7%) analyzed computed tomography, six studies (15.8%) applied AI to magnetic resonance imaging, and one study (2.63%) analyzed panoramic radiography. Laryngoscopic and otoscopic imaging were addressed in three studies each (7.89% each). The remaining seven studies (18.39%) used AI to aid in the analysis of neuroimaging biomarker levels, biopsy specimens, simulated Raman scattering data, ultrasonography and mass spectrometry data, and digitized images. Nearly all AI algorithms comprised convolutional neural networks. Fig. 3 presents a schematic diagram of the application of convolutional neural networks in medical image-based analysis; the remaining algorithms consisted of support vector machines and random forests.

Table 1.

AI techniques used for medical image-based analysis

| Study | Analysis modality | Objective | AI technique | Validation method | No. of samples in the training dataset | No. of samples in the testing dataset | Best result |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (%)/AUC | Sensitivity (%)/specificity (%) | |||||||

| [20] | CT | Anterior ethmoidal artery anatomy | CNN: Inception-V3 | Hold-out | 675 Images from 388 patients | 197 Images | 82.7/0.86 | - |

| [21] | CT | Osteomeatal complex occlusion | CNN: Inception-V3 | - | 1.28 Million images from 239 patients | - | 85.0/0.87 | - |

| [22] | CT | Chronic otitis media diagnosis | CNN: Inception-V3 | Hold-out | 975 Images | 172 Images | -/0.92 | 83.3/91.4 |

| [23] | DECT | HNSCC lymph nodes | RF, GBM | Hold-out | Training and testing set are randomly chosen with a ratio 70:30 from a total of 412 lymph nodes from 50 patients. | 90.0/0.96 | 89.0/91.0 | |

| [24] | microCT | Intratemporal facial nerve anatomy | PCA+SSM | - | 40 Cadaveric specimens from 21 donors | - | - | - |

| [25] | CT | Extranodal extension of HNSCC | CNN | Hold out | 2,875 Lymph nodes | 200 Lymph nodes | 83.1/0.84 | 71.0/85.0 |

| [26] | CT | Prediction of overall survival of head and neck cancer | NN, DT, boosting, Bayesian, bagging, RF, MARS, SVM, k-NN, GLM, PLSR | 10-CV | 101 Head and neck cancer patients, 440 radiomic features | -/0.67 | - | |

| [27] | DECT | Benign parotid tumors classification | RF | Hold-out | 882 Images from 42 patients | Two-thirds of the samples | 92.0/0.97 | 86.0/100 |

| [28] | fMRI | Predicting the language outcomes following cochlear implantation | SVM | LOOCV | 22 Training samples, including 15 labeled samples and 7 unlabeled samples | 81.3/0.97 | 77.8/85.7 | |

| [29] | fMRI | Auditory perception | SVM | 10-CV | 42 Images from 6 participants | 47.0/- | - | |

| [30] | MRI | Relationship between tinnitus and thicknesses of internal auditory canal and nerves | ELM | Repeated hold-out | 46 Images from 23 healthy subjects and 23 patients. Test was repeated 10 times for three training ratios, i.e., 50%, 60%, and 70%. | 94.0/- | - | |

| [31] | MRI | Prediction of treatment outcomes of sinonasal squamous cell carcinomas | SVM | 9-CV | 36 Lesions from 36 patients | 92.0/- | 100/82.0 | |

| [32] | Neuroimaging biomarkers | Tinnitus | SVM | 5-CV | 102 Images from 46 patients and 56 healthy subjects | 80.0/0.86 | - | |

| [33] | MRI | Differentiate sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma from inverted papilloma | SVM | LOOCV | 22 Patients with inverted papilloma and 24 patients with SCC | 89.1/- | 91.7/86.4 | |

| [34] | MRI | Speech improvement for CI candidates | SVM | LOOCV | 37 Images from 37 children with hearing loss and 40 images from 40 children with normal hearing | 84.0/0.84 | 80.0/88.0 | |

| [35] | Endoscopic images | Laryngeal soft tissue | Weighted voting (UNet+ErfNet) | Hold-out | 200 Images | 100 Images | 84.7/- | - |

| [36] | Laryngoscope images | laryngeal neoplasms | CNN | Hold-out | 14,340 Images from 5,250 patients | 5,093 Images from 2,271 patients | 96.24/- | 92.8/98.9 |

| [37] | Laryngoscope images | Laryngeal cancer | CNN | Hold-out | 13,721 Images | 1,176 Images | 86.7/0.92 | 73.1/92.2 |

| [38] | Laryngoscope images | Oropharyngeal cariconoma | Naive Bayes | Hold-out | 4 Patients with oropharyngeal cariconoma and 1 healthy subject | 16 Patients with oropharyngeal cariconoma and 9 healthy subjects | 65.9/- | 66.8/64.9 |

| [39] | Otoscopic images | Otologic diseases | CNN | Hold-out | 734 Images; 80% of the images were used for the training and 20% were used for validation. | 84.4/- | - | |

| [40] | Otoscopic images | Otitis media | MJSR | Hold-out | 1,230 Images; 80% of and 20% were used the images were used for the training for validation. | 91.41/- | 89.48/93.33 | |

| [41] | Otoscopic images | Otoscopic diagnosis | AutoML | Hold-out | 1,277 Images | 89 Images | 88.7/- | 86.1/- |

| [42] | Digitized images | H&E-stained tissue of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma | LDA, QDA, RF, SVM | Hold-out | 50 Images | 65 Images | 88.0/0.87 | 78.0/93.0 |

| [43] | PESI-MS | Intraoperative specimens of HNSCC | LR | LOOCV | 114 Non-cancerous specimens and 141 cancerous specimens | 95.35/- | - | |

| [44] | Biopsy specimen | Frozen section of oral cavity cancer | SVM | LOOCV | 176 Specimen pairs from 27 subjects | -/0.94 | 100/88.78 | |

| [45] | HSI | Head and neck cancer classification | CNN | LOOCV | 88 Samples from 50 patients | 80.0/- | 81.0/78.0 | |

| [46] | HSI | Head and neck cancer classification | CNN | LOOCV | 12 Tumor-bearing samples for 12 mice | 91.36/- | 86.05/93.36 | |

| [47] | HSI | Oral cancer | SVM, LDA, QDA, RF, RUSBoost | 10-CV | 10 Images from 10 mice | 79.0/0.86 | 79.0/79.0 | |

| [48] | HSI | Head and neck cancer classification | LDA, QDA, ensemble LDA, SVM, RF | Repeated hold-out | 20 Specimens from 20 patients | 16 Specimens from 16 patients | 94.0/0.97 | 95.0/90.0 |

| [49] | HSI | Tissue surface shape reconstruction | SSRNet | 5-CV | 200 SL images | 96.81/- | 92.5/- | |

| [50] | HSI | Tumor margin of HNSCC | CNN | 5-CV | 395 Surgical specimens | 98.0/0.99 | - | |

| [51] | HSI | Tumor margin of HNSCC | LDA | 10-CV | 16 Surgical specimens | 90.0/- | 89.0/91.0 | |

| [52] | HSI | Optical biopsy of head and neck cancer | CNN | LOOCV | 21 Surgical gross-tissue specimens | 81.0/0.82 | 81.0/80.0 | |

| [53] | SRS | Frozen section of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma | CNN | 5-CV | 18,750 Images from 45 patients | 100/- | - | |

| [54] | HSI | Cancer margins of ex-vivo human surgical specimens | CNN | Hold-out | 11 Surgical specimens | 9 Surgical specimens | 81.0/0.86 | 84.0/77.0 |

| [55] | USG | Genetic risk stratification of thyroid nodules | AutoML | Hold-out | 556 Images from 21 patients | 127 Images | 77.4/- | 45.0/97.0 |

| [56] | CT | Concha bullosa on coronal sinus classification | CNN: Inception-V3 | Hold-out | 347 Images (163 concha bullosa images and 184 normal images) | 100 Images (50 concha bullosa images and 50 normal images) | 81.0/0.93 | - |

| [57] | Panoramic radiography | Maxillary sinusitis diagnosis | AlexNet CNN | Hold-out | 400 Healthy images and 400 inflamed maxillary sinuses images | 60 Healthy and 60 inflamed maxillary sinuses images | 87.5/0.875 | 86.7/88.3 |

AI, artificial intelligence; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CT, computed tomography; CNN, convolutional neural network; DECT, dual-energy computed tomography; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; RF, random forest; GBM, gradient boosting machine; PCA, principle component analysis; SSM, statistical shape model; NN, neural network; DT, decision tree; MARS, multi adaptive regression splines; SVM, support vector machine; k-NN, k-nearest neighbor; GLM, generalized linear model; PLSR, partial least squares and principal component regression; CV, cross-validation; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; LOOCV, leave-one-out cross-validation; ELM, extreme learning machine; CI, cochlear implant; MJSR, multitask joint sparse representation; LDA, linear discriminant analysis; QDA, quadratic discriminant analysis; PESI-MS, probe electrospray ionization mass spectrometry; LR, logistic regression; HSI, hyperspectral imaging; SSRNet, super-spectral-resolution network; SRS, stimulated Raman scattering; USG, ultrasonography.

Fig. 3.

Artificial intelligence (AI) techniques used for medical image-based analysis.

AI aids voice-based analysis

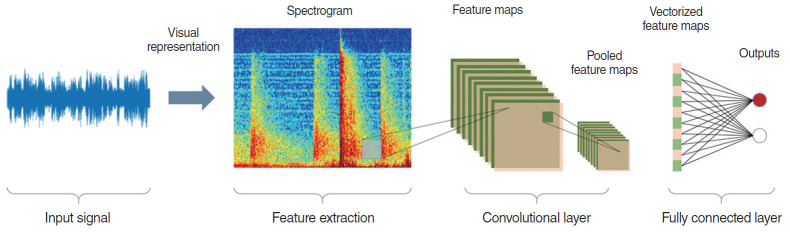

The subfield of voice-based analysis within otorhinolaryngology seeks to improve speech, to detect voice disorders, and to reduce the noise experienced by patients with (CIs; Table 2 lists the 14 studies that used AI for speech-based analyses. Nine (64.29%) sought to improve speech intelligibility or reduce noise for patients with CIs. Two (14.29%) used acoustic signals to detect voice disorders [67] and “hot potato voice” [70]. In other studies, AI was used for symptoms, voice pathologies, or electromyographic signals as a way to detect voice disorders [68,69], or to restore the voice of a patient who had undergone total laryngectomy [71]. Neural networks were favored, followed by k-nearest neighbor methods, support vector machines, and other widely known classifiers (e.g., decision trees and XGBoost). Fig. 4 presents a schematic diagram of the application of convolutional neural networks in medical voice-based analysis.

Table 2.

AI techniques used for voice-based analysis

| Study | Analysis modality | Objective | AI technique | Validation method | No. of samples in the training dataset | No. of samples in the testing dataset | Best result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [58] | CI | Noise reduction | NC+DDAE | Hold-out | 120 Utterances | 200 Utterances | Accuracy: 99.5% |

| [59] | CI | Segregated speech from background noise | DNN | Hold-out | 560×50 Mixtures for each noise type and SNR | 160 Noise segments from original unperturbed noise | Hit ratio: 84%; false alarm: 7% |

| [60] | CI | Improved pitch perception | ANN | Hold-out | 1,500 Pitch pairs | 10% of the training material | Accuracy: 95% |

| [61] | CI | Predicted speech recognition and QoL outcomes | k-NN, DT | 10-CV | A total of 29 patients, including 48% unilateral CI users and 51% bimodal CI users | Accuracy: 81% | |

| [62] | CI | Noise reduction | DDAE | Hold-out | 12,600 Utterances | 900 Noisy utterances | Accuracy: 36.2% |

| [63] | CI | Improved speech intelligibility in unknown noisy environments | DNN | Hold-out | 640,000 Mixtures of sentences and noises | - | Accuracy: 90.4% |

| [64] | CI | Modeling electrode-to-nerve interface | ANN | Hold-out | 360 Sets of fiber activation patterns per electrode | 40 Sets of fiber activation patterns per electrode | - |

| [65] | CI | Provided digital signal processing plug-in for CI | WNN | Hold-out | 120 Consonants and vowels, sampled at 16 kHz; half of data was used as training set and the rest was used as testing set. | SNR: 2.496; MSE: 0.086; LLR: 2.323 | |

| [66] | CI | Assessed disyllabic speech test performance in CI | k-NN | - | 60 Patients | - | Accuracy: 90.83% |

| [67] | Acoustic signals | Voice disorders detection | CNN | 10-CV | 451 Images from 10 health adults and 70 adults with voice disorders | Accuracy: 90% | |

| [68] | Dysphonic symptoms | Voice disorders detection | ANN | Repeated hold-out | 100 Cases of neoplasm, 508 cases of benign phonotraumatic, 153 cases of vocal palsy | Accuracy: 83% | |

| [69] | Pathological voice | Voice disorders detection | DNN, SVM, GMM | 5-CV | 60 Normal voice samples and 402 pathological voice samples | Accuracy: 94.26% | |

| [70] | Acoustic signal | Hot potato voice detection | SVM | Hold-out | 2,200 Synthetic voice samples | 12 HPV samples from real patients | Accuracy: 88.3% |

| [71] | SEMG signals | Voice restoration for laryngectomy patients | XGBoost | Hold-out | 75 Utterances using 7 SEMG sensors | - | Accuracy: 86.4% |

AI, artificial intelligence; CI, cochlear implant; NC, noise classifier; DDAE, deep denoising autoencoder; DNN, deep neural network; SNR, signal-to-noise ratio; ANN, artificial neural network; QoL, quality of life; k-NN, k-nearest neighbors; DT, decision tree; CV, cross-validation; WNN, wavelet neural network; MSE, mean square error; LLR, log-likelihood ratio; CNN, convolutional neural network; GMM, Gaussian mixture model; SVM, support vector machine; HPV, human papillomavirus; SEMG, surface electromyographic.

Fig. 4.

Artificial intelligence (AI) techniques used for voice-based analysis.

AI analysis of biosignals detected from medical devices

Medical device-based analyses seek to predict the responses to clinical treatments in order to guide physicians who may wish to choose alternative or more aggressive therapies. AI has been used to assist polysomnography, to explore gene expression profiles, to interpret cellular cartographs, and to evaluate the outputs of non-contact devices. These studies are summarized in Table 3. Of these 14 studies, most (50%, seven studies) focused on analyses of gene expression data. Three studies (21.43%) used AI to examine polysomnography data in an effort to score sleep stages [72,73] or to identify long-term cardiovascular disease [74]. Most algorithms employed ensemble learning (random forests, Gentle Boost, XGBoost, and a general linear model+support vector machine ensemble); this approach was followed by neural networkbased algorithms (convolutional neural networks, autoencoders, and shallow artificial neural networks). Fig. 5 presents a schematic diagram of the application of the autoencoder and the support vector machine in the analysis of gene expression data.

Table 3.

AI analysis of biosignals detected from medical device

| Study | Analysis modality | Objective | AI technique | Validation method | No. of samples in the training dataset | No. of samples in the testing dataset | Best result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [73] | EEG signal of PSG | Sleep stage scoring | CNN | 5-CV | 294 Sleep studies; 122 composed the training set, 20 composed the validation set, and 152 were used in the testing set. | Accuracy: 81.81%; F1 score: 81.50%; Cohen’s Kappa: 72.76% | |

| [72] | EEG, EMG, EOG signals of PSG | Sleep stage scoring | CNN | Hold-out | 42,560 Hours of PSG data from 5,213 patients | 580 PSGs | Accuracy: 86%; F1 score: 81.0%; Cohen’s Kappa: 82.0% |

| [74] | Sleep heart rate variability in PSG | Long-term cardiovascular outcome prediction | XGBoost | 5-CV | 1,252 Patients with cardio vascular disease and 859 patients with non-cardio vascular disease | Accuracy: 75.3% | |

| [87] | Sleep breathing sound using an air-conduction microphone | AHI prediction | Gaussian process, SVM, RF, LiR | 10-CV | 116 Patients with OSA | CC: 0.83; LMAE: 9.54 events/hr; RMSE: 13.72 events/hr | |

| [88] | Gene signature | Thyroid cancer lymph node metastasis and recurrence rediction | LDA | 6-CV | 363 Samples | 72 Samples | AUC: 0.86; sensitivity: 86%; specificity: 62%; PPV: 93%; NPV: 42% |

| [89] | Gene expression profile | Response prediction to chemotherapy in patient with HNSCC | SVM | LOOCV | 16 TPF-sensitive patients and 13 non-TPF-sensitive patients | Sensitivity: 88.3%; specificity: 88.9% | |

| [90] | Mucus cytokines | SNOT-22 scores prediction of CRS patients | RF, LiR | - | 147 Patients with 65 patients with postoperative follow-up | R2: 0.398 | |

| [91] | Cellular cartography | Single-cell resolution mapping of the organ of Corti | Gentle boost, RF, CNN | Hold-out | 20,416 Samples | 19,594 Samples | Recall: 99.3%; precision: 99.3%; F1: 93.3% |

| [92] | RNA sequencing, miRNA sequencing, methylation data | HNSCC progress prediction | Autoencoder and SVM | 2×5-CV | 360 Samples from TCGA | C-index: 0.73; Brier score: 0.22 | |

| [93] | DNA repair defect | HNSCC progress prediction | CART | 10×5-CV | 180 HPV-negative HNSCC patients | AUC: 1.0 | |

| [94] | PESI-MS | Identified TGF-β signaling in HNSCC | LDA | LOOCV | A total of 240 and 90 mass spectra from TGF-β-unstimulated and stimulated HNSCC cells, respectively | Accuracy: 98.79% | |

| [95] | Next generation sequencing of RNA | Classified the risk of malignancy in cytologically indeterminate thyroid nodules | Ensemble of elastic net GLM and SVM | 40×5-CV | A total of 10,196 genes, among which are 1,115 core genes | Sensitivity: 91%; specificity: 68% | |

| [96] | Gene expression profile | HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma detection | LR | 500-CV | 146 Genes from patients with node-negative disease and node-positive disease | AUC: 0.93 | |

| [97] | miRNA expression profile | Sensorineural hearing loss prediction | DF, DJ, LR, NN | LOOCV | 16 Patients were included. | Accuracy: 100% | |

AI, artificial intelligence; EEG, electroencephalogram; PSG, polysomnography; CNN, convolutional neural network; CV, cross-validation; EMG, electromyography; EOG, electrooculogram; AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; SVM, support vector machine; RF, random forest; LiR, linear regression; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; CC, correlation coefficient; LMAE, least mean absolute error; RMSE, root mean squared error; LDA, linear discriminant analysis; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; LOOCV, leave-one-out cross validation; TPF, docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil; SNOT-22, 22-item sinonasal outcome test; CRS, chronic rhinosinusitis; miRNA, microRNA; TCGA, the cancer genome atlas; CART, classification and regression trees; HPV, human papillomavirus; PESI-MS, probe electrospray ionization mass spectrometry; TGF-β, transforming growth factor beta; GLM, generalized linear model; LR, logistic regression; DF, decision forest; DJ, decision jungle; NN, neural network.

Fig. 5.

Artificial intelligence (AI) analyses of biosignals detected from medical devices. SVM, support vector machine.

AI for clinical diagnoses and treatments

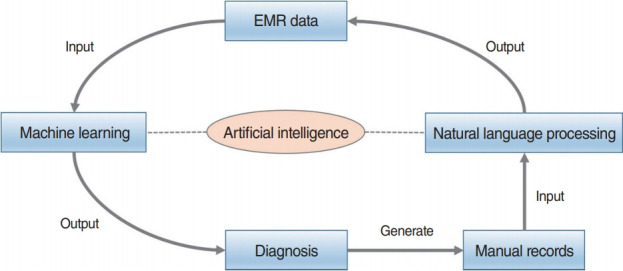

Clinical diagnoses and treatments consider only symptoms, medical records, and other clinical documentation. We retrieved 24 relevant studies (Table 4). Of the ML algorithms, most used logistic regression for classification, followed by random forests and support vector machines. Notably, many studies used hold-outs to validate new methods. Fig. 6 presents a schematic diagram of the process cycle of utilizing AI for clinical diagnoses and treatments.

Table 4.

AI techniques used for clinical diagnoses and treatments

| Study | Analysis modality | Objective | AI technique | Validation method | No. of samples in the training dataset | No. of samples in the testing dataset | Best result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [98] | Hearing aids | Hearing gain prediction | CRDN | Hold-out | 2,182 Patients that were diagnosed with hearing loss; the percentages of randomly sampled training, validation, and test sets were 40%, 30%, and 30%, respectively. | MAPE: 9.2% | |

| [99] | Hearing aids | Predicted CI outcomes | RF | LOOCV | 121 Postlingually deaf adults with CI | MAE: 6.1; Pearson’s correlation coefficient: 0.96 | |

| [100] | Clinical data | SSHL prediction | DBN, LR, SVM, MLP | 4-CV | 1,220 Unilateral SSHL patients | Accuracy: 77.58%; AUC: 0.84 | |

| [101] | Clinical data including demographics and risk factors | Determined the risk of head and neck cancer | LR | Hold-out | 1,005 Patients, containing 932 patients with no cancer outcome and 73 patients with cancer outcome | 235 Patients, containing 212 patients with no cancer outcome and 23 patients with cancer outcome | AUC: 0.79 |

| [102] | Clinical data including symptom | Peritonsillar abscess diagnosis prediction | NN | Hold-out | 641 Patients | 275 Patients | Accuracy: 72.3%; sensitivity: 6.0%; specificity: 50% |

| [103] | Vestibular test batteries | Vestibular function assessment | DT, RF, LR, AdaBoost, SVM | Hold-out | 5,774 Individuals | 100 Individuals | Accuracy: 93.4% |

| [104] | Speakers and microphones within existing smartphones | Middle ear fluid detection | LR | LOOCV | 98 Patient ears | AUC: 0.9; sensitivity: 84.6%; specificity: 81.9% | |

| [105] | Cancer data survival | 5-Year survival patients with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma | DF, DJ, LR, NN | Hold-out | 26,452 Patients | 6,613 Patients | AUC: 0.8; accuracy: 71%; precision: 71%; recall: 68% |

| [106] | Histological data | Occult lymph node metastases identification in clinically oral cavity squamous cell | RF, SVM, LR, C5.0 | Hold-out | 56 Patients | 112 Patients | AUC: 0.89; accuracy: 88.0%; NPV: >95% |

| [107] | Clinicopathologic data | Head and neck free tissue transfer surgical complications prediction | GBDT | Hold-out | 291 Patients | 73 Patients | Specificity: 62.0%; sensitivity: 60.0%; F1: 60.0% |

| [108] | Clinicopathologic data | Delayed adjuvant radiation prediction | RF | Hold-out | 61,258 Patients | 15,315 Patients | Accuracy: 64.4%; precision: 58.5% |

| [109] | Clinicopathologic data | Occult nodal metastasis prediction in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma | LR, RF, SVM, GBM | Hold-out | 1,570 Patients | 391 Patients | AUC: 0.71; sensitivity: 75.3%; specificity: 49.2% |

| [110] | Dataset of the center of pressure sway during foam posturography | Peripheral vestibular dysfunction prediction | GBDT, bagging, LR | CV | 75 Patients with vestibular dysfunction and 163 healthy controls | AUC: 0.9; recall: 0.84 | |

| [111] | TEOAE signals | Meniere’s disease hearing outcome prediction | SVM | 5-CV | 30 Unilateral patients | Accuracy: 82.7% | |

| [112] | Semantic and syntactic patterns in clinical documentation | Vestibular diagnoses | NLP+Naïve Bayes | 10-CV | 866 Physician-generated histories from vestibular patients | Sensitivity: 93.4%; specificity: 98.2%; AUC: 1.0 | |

| [113] | Endoscopic imaging | Nasal polyps diagnosis | ResNet50, Xception, and Inception V3 | Hold-out | 23,048 Patches (167 patients) as training set, 1,577 patches (12 patients) as internal validation set, and 1,964 patches (16 patients) as external test set | Inception V3: AUC: 0.974 | |

| [114] | Intradermal skin tests | Allergic rhinitis diagnosis | Associative classifier | 10-CV | 872 Patients with allergic symptoms | Accuracy: 88.31% | |

| [115] | Clinical data | Identified phenotype and mucosal eosinophilia endotype subgroups of patients with medical refractory CRS | Cluster analysis | - | 46 Patients with CRS without nasal polyps and 67 patients with nasal polyps | - | |

| [116] | Clinical data | Prognostic information of patient with CRS | Discriminant analysis | - | 690 Patients | - | |

| [117] | Clinical data | Identified phenotypic subgroups of CRS patients | Discriminant analysis | - | 382 Patients | - | |

| [118] | Clinical data | Characterization of distinguishing clinical features between subgroups of patients with CRS | Cluster analysis | - | 97 Surgical patients with CRS | - | |

| [119] | Clinical data | Identified features of CRS without nasal polyposis | Cluster analysis | - | 145 Patients of CRS without nasal polyposis | - | |

| [120] | Clinical data | Identified inflammatory endotypes of CRS | Cluster analysis | - | 682 Cases (65% with CRS without nasal polyps) | - | |

| [121] | Clinical data | Identified features of CRS with nasal polyps | Cluster analysis | - | 375 Patients | - | |

AI, artificial intelligence; CRDN, cascade recurring deep network; MAPE, mean absolute percentage error; RF, random forest; LOOCV, leave-one-out cross validation; CI, cochlear implant; MAE, mean absolute error; SSHL, sudden sensorineural hearing loss; DBN, deep belief network; LR, logistic regression; SVM, support vector machine; MLP, multilayer perceptron; CV, cross-validation; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; NN, neural network; DT, decision tree; DF, decision forest; DJ, decision jungle; NPV, negative predictive value; GBDT, gradient boosted decision trees; GBM, gradient boosting machine; TEOAE, transient-evoked otoacoustic emission; NLP, natural language processing; CRS, chronic rhinosinusitis.

Fig. 6.

Artificial intelligence (AI) techniques used for clinical diagnoses and treatments. EMR, electronic medical record.

DISCUSSION

We systematically analyzed reports describing the integration of AI in the field of otorhinolaryngology, with an emphasis on how AI may best be implemented in various subfields. Various AI techniques and validation methods have found favor. As described above, advances in 2015 underscored that AI would play a major role in future medicine. Here, we reviewed post-2015 AI applications in the field of otorhinolaryngology. Before 2015, most AI-based technologies focused on CIs [10,75-86]. However, AI applications have expanded greatly in recent years. In terms of image-based analysis, images yielded by rigid endoscopes, laryngoscopes, stroboscopes, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and multispectral narrow-band imaging [38], as well as hyperspectral imaging [45-52,54], are now interpreted by AI. In voice-based analysis, AI is used to evaluate pathological voice conditions associated with vocal fold disorders, to analyze and decode phonation itself [67], to improve speech perception in noisy conditions, and to improve the hearing of patients with CIs. In medical device-based analyses, AI is used to evaluate tissue and blood test results, as well as the outcomes of otorhinolaryngology-specific tests (e.g., polysomnography) [72,73,122] and audiometry [123,124]. AI has also been used to support clinical diagnoses and treatments, decision-making, the prediction of prognoses [98-100,125,126], disease profiling, the construction of mass spectral databases [43,127-129], the identification or prediction of disease progress [101,105,107-110,130], and the confirmation of diagnoses and the utility of treatments [102-104,112,131].

Although many algorithms have been applied, some are not consistently reliable, and certain challenges remain. AI will presumably become embedded in all tools used for diagnosis, treatment selection, and outcome predictions; thus, AI will be used to analyze images, voices, and clinical records. These are the goals of most studies, but again, the results have been variable and are thus difficult to compare. The limitations include: (1) small training datasets and differences in the sizes of the training and test datasets; (2) differences in validation techniques (notably, some studies have not included data validation); and (3) the use of different performance measures during either classification (e.g., accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, F1, or area under the receiver operating characteristic curve) or regression (e.g., root mean square error, least mean absolute error, R-squared, or log-likelihood ratio).

ML algorithms always require large, labeled training datasets. The lack of such data was often a major limitation of the studies that we reviewed. AI-based predictions in the field of otorhinolaryngology must be rigorously validated. Often, as in the broader medical field, an element of uncertainty compromises an otherwise ideal predictive method, and other research disparities were also apparent in the studies that we reviewed. Recent promising advances in AI include the ensemble learning model, which is more intuitive and interpretable than other models; this model facilitates bias-free AI-based decision-making. The algorithm incorporates a concept of “fairness,” considers ethical and legal issues, and respects privacy during data mining tasks. In summary, although otorhinolaryngology-related AI applications were divided into four categories in the present study, the practical use of a particular AI method depends on the circumstances. AI will be helpful for use in real-world clinical treatment involving complex datasets with heterogeneous variables.

CONCLUSION

We have described several techniques and applications for AI; notably, AI can overcome existing technical limitations in otorhinolaryngology and aid in clinical decision-making. Otorhinolaryngologists have interpreted instrument-derived data for decades, and many algorithms have been developed and applied. However, the use of AI will refine these algorithms, and big health data and information from complex heterogeneous datasets will become available to clinicians, thereby opening new diagnostic, treatment, and research frontiers.

HIGHLIGHTS

▪ Ninety studies that implemented artificial intelligence (AI) in otorhinolaryngology were reviewed and classified.

▪ The studies were divided into four subcategories.

▪ Research challenges regarding future applications of AI in otorhinolaryngology are discussed.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through an NRF grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2020R1A2C1009744), the Bio Medical Technology Development Program of the NRF funded by the Ministry of Science ICT (No. 2018M3A9E8020856), and the Po-Ca Networking Group funded by the Postech-Catholic Biomedical Engineering Institute (PCBMI) (No. 5-2020-B0001-00046).

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: DHK, SWK, SL. Data curation: BAT, DHK, GK. Formal analysis: BAT, DHK, GK. Funding acquisition: DHK, SL. Methodology: BAT, DHK, GK. Project administration: DHK, SWK, SL. Visualization: BAT, DHK, GK. Writing–original draft: BAT, DHK. Writing–review & editing: all authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pomerol JC. Artificial intelligence and human decision making. Eur J Oper Res. 1997 May;99(1):3–25. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon HA. The sciences of the artificial. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J, editors. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silver D, Hassabis D, editors. Google AI Blog; 2016. Alphago: mastering the ancient game of go with machine learning [Internet] [cited 2020 Aug 1]. Available from: https://ai.googleblog.com/2016/01/alphagomastering-ancient-game-of-go.html. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Densen P. Challenges and opportunities facing medical education. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2011;122:48–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monegain B, editor. Healthcare IT News; 2016. IBM Watson pinpoints rare form of leukemia after doctors misdiagnosed patient [Internet] [cited 2020 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/ibm-watson-pinpoints-rare-form-leukemia-after-doctors-misdiagnosed-patient. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grand View Research . San Francisco, CA: Grand View Research; 2019. Artificial intelligence in healthcare market size, share & trends analysis by component (hardware, software, services), by application, by region, competitive insights, and segment forecasts, 2019-2025 [Internet] [cited 2020 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/artificial-intelligence-ai-healthcare-market. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crowson MG, Ranisau J, Eskander A, Babier A, Xu B, Kahmke RR, et al. A contemporary review of machine learning in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery. Laryngoscope. 2020 Jan;130(1):45–51. doi: 10.1002/lary.27850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freeman DT, editor. Computer recognition of brain stem auditory evoked potential wave V by a neural network. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1991:305–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zadak J, Unbehauen R. An application of mapping neural networks and a digital signal processor for cochlear neuroprostheses. Biol Cybern. 1993;68(6):545–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00200814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim DH, Kim Y, Park JS, Kim SW. Virtual reality simulators for endoscopic sinus and skull base surgery: the present and future. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2019 Feb;12(1):12–7. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2018.00906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park JH, Jeon HJ, Lim EC, Koo JW, Lee HJ, Kim HJ, et al. Feasibility of eye tracking assisted vestibular rehabilitation strategy using immersive virtual reality. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2019 Nov;12(4):376–84. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2018.01592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song JJ. Virtual reality for vestibular rehabilitation. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2019 Nov;12(4):329–30. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2019.00983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chollet F, Allaire JJ. Deep learning with R. Shelter Island (NY): Manning Publications; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohri M, Rostamizadeh A, Talwalkar A. Foundations of machine learning. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flach P. Machine learning: the art and science of algorithms that make sense of data. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.James G, Witten D, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. An introduction to statistical learning. Berlin: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G. Deep learning. Nature. 2015 May;521(7553):436–44. doi: 10.1038/nature14539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tama BA, Rhee KH. Tree-based classifier ensembles for early detection method of diabetes: an exploratory study. Artif Intell Rev. 2019;51:355–70. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang J, Habib AR, Mendis D, Chong J, Smith M, Duvnjak M, et al. An artificial intelligence algorithm that differentiates anterior ethmoidal artery location on sinus computed tomography scans. J Laryngol Otol. 2020 Jan;134(1):52–5. doi: 10.1017/S0022215119002536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chowdhury NI, Smith TL, Chandra RK, Turner JH. Automated classification of osteomeatal complex inflammation on computed tomography using convolutional neural networks. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019 Jan;9(1):46–52. doi: 10.1002/alr.22196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang YM, Li Y, Cheng YS, He ZY, Yang JM, Xu JH, et al. Automated classification of osteomeatal complex inflammation on computed tomography using convolutional neural networks. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019 Jan;9(1):46–52. doi: 10.1002/alr.22196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seidler M, Forghani B, Reinhold C, Perez-Lara A, Romero-Sanchez G, Muthukrishnan N, et al. Dual-energy CT texture analysis with machine learning for the evaluation and characterization of cervical lymphadenopathy. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2019 Jul;17:1009–15. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hudson TJ, Gare B, Allen DG, Ladak HM, Agrawal SK. Intrinsic measures and shape analysis of the intratemporal facial nerve. Otol Neurotol. 2020 Mar;41(3):e378–86. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kann BH, Hicks DF, Payabvash S, Mahajan A, Du J, Gupta V, et al. Multi-institutional validation of deep learning for pretreatment identification of extranodal extension in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Apr;38(12):1304–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parmar C, Grossmann P, Rietveld D, Rietbergen MM, Lambin P, Aerts HJ. Radiomic machine-learning classifiers for prognostic biomarkers of head and neck cancer. Front Oncol. 2015 Dec;5:272. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al Ajmi E, Forghani B, Reinhold C, Bayat M, Forghani R. Spectral multi-energy CT texture analysis with machine learning for tissue classification: an investigation using classification of benign parotid tumours as a testing paradigm. Eur Radiol. 2018 Jun;28(6):2604–11. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5214-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan L, Holland SK, Deshpande AK, Chen Y, Choo DI, Lu LJ. A semi-supervised support vector machine model for predicting the language outcomes following cochlear implantation based on pre-implant brain fMRI imaging. Brain Behav. 2015 Oct;5(12):e00391. doi: 10.1002/brb3.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang F, Wang JP, Kim J, Parrish T, Wong PC. Decoding multiple sound categories in the human temporal cortex using high resolution fMRI. PLoS One. 2015 Feb;10(2):e0117303. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ergen B, Baykara M, Polat C. Determination of the relationship between internal auditory canal nerves and tinnitus based on the findings of brain magnetic resonance imaging. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2018 Feb;40:214–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujima N, Shimizu Y, Yoshida D, Kano S, Mizumachi T, Homma A, et al. Machine-learning-based prediction of treatment outcomes using MR imaging-derived quantitative tumor information in patients with sinonasal squamous cell carcinomas: a preliminary study. Cancers (Basel) 2019 Jun;11(6):800. doi: 10.3390/cancers11060800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Niu H, Zhu J, Zhao P, Yin H, Ding H, et al. Morphological neuroimaging biomarkers for tinnitus: evidence obtained by applying machine learning. Neural Plast. 2019 Dec;2019:1712342. doi: 10.1155/2019/1712342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramkumar S, Ranjbar S, Ning S, Lal D, Zwart CM, Wood CP, et al. MRI-based texture analysis to differentiate sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma from inverted papilloma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017 May;38(5):1019–25. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng G, Ingvalson EM, Grieco-Calub TM, Roberts MY, Ryan ME, Birmingham P, et al. Neural preservation underlies speech improvement from auditory deprivation in young cochlear implant recipients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018 Jan;115(5):E1022–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717603115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laves MH, Bicker J, Kahrs LA, Ortmaier T. A dataset of laryngeal endoscopic images with comparative study on convolution neural network-based semantic segmentation. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2019 Mar;14(3):483–92. doi: 10.1007/s11548-018-01910-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ren J, Jing X, Wang J, Ren X, Xu Y, Yang Q, et al. Automatic recognition of laryngoscopic images using a deep-learning technique. Laryngoscope. 2020 Feb 18; doi: 10.1002/lary.28539. [Epub]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiong H, Lin P, Yu JG, Ye J, Xiao L, Tao Y, et al. Computer-aided diagnosis of laryngeal cancer via deep learning based on laryngoscopic images. EBioMedicine. 2019 Oct;48:92–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.08.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mascharak S, Baird BJ, Holsinger FC. Detecting oropharyngeal carcinoma using multispectral, narrow-band imaging and machine learning. Laryngoscope. 2018 Nov;128(11):2514–20. doi: 10.1002/lary.27159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Livingstone D, Talai AS, Chau J, Forkert ND. Building an otoscopic screening prototype tool using deep learning. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Nov;48(1):66. doi: 10.1186/s40463-019-0389-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tran TT, Fang TY, Pham VT, Lin C, Wang PC, Lo MT. Development of an automatic diagnostic algorithm for pediatric otitis media. Otol Neurotol. 2018 Sep;39(8):1060–5. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Livingstone D, Chau J. Otoscopic diagnosis using computer vision: an automated machine learning approach. Laryngoscope. 2020 Jun;130(6):1408–13. doi: 10.1002/lary.28292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu C, Lewis JS, Jr, Dupont WD, Plummer WD, Jr, Janowczyk A, Madabhushi A. An oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma quantitative histomorphometric-based image classifier of nuclear morphology can risk stratify patients for disease-specific survival. Mod Pathol. 2017 Dec;30(12):1655–65. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2017.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashizawa K, Yoshimura K, Johno H, Inoue T, Katoh R, Funayama S, et al. Construction of mass spectra database and diagnosis algorithm for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2017 Dec;75:111–9. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2017.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grillone GA, Wang Z, Krisciunas GP, Tsai AC, Kannabiran VR, Pistey RW, et al. The color of cancer: margin guidance for oral cancer resection using elastic scattering spectroscopy. Laryngoscope. 2017 Sep;127 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):S1–9. doi: 10.1002/lary.26763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Halicek M, Lu G, Little JV, Wang X, Patel M, Griffith CC, et al. Deep convolutional neural networks for classifying head and neck cancer using hyperspectral imaging. J Biomed Opt. 2017 Jun;22(6):60503. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.22.6.060503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma L, Lu G, Wang D, Wang X, Chen ZG, Muller S, et al. Deep learning based classification for head and neck cancer detection with hyperspectral imaging in an animal model. Proc SPIE Int Soc Opt Eng. 2017 Feb;10137:101372G. doi: 10.1117/12.2255562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu G, Wang D, Qin X, Muller S, Wang X, Chen AY, et al. Detection and delineation of squamous neoplasia with hyperspectral imaging in a mouse model of tongue carcinogenesis. J Biophotonics. 2018 Mar;11(3):e201700078. doi: 10.1002/jbio.201700078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu G, Little JV, Wang X, Zhang H, Patel MR, Griffith CC, et al. Detection of head and neck cancer in surgical specimens using quantitative hyperspectral imaging. Clin Cancer Res. 2017 Sep;23(18):5426–36. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin J, Clancy NT, Qi J, Hu Y, Tatla T, Stoyanov D, et al. Dual-modality endoscopic probe for tissue surface shape reconstruction and hyperspectral imaging enabled by deep neural networks. Med Image Anal. 2018 Aug;48:162–76. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Halicek M, Dormer JD, Little JV, Chen AY, Myers L, Sumer BD, et al. Hyperspectral imaging of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma for cancer margin detection in surgical specimens from 102 patients using deep learning. Cancers (Basel) 2019 Sep;11(9):1367. doi: 10.3390/cancers11091367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fei B, Lu G, Wang X, Zhang H, Little JV, Patel MR, et al. Label-free reflectance hyperspectral imaging for tumor margin assessment: a pilot study on surgical specimens of cancer patients. J Biomed Opt. 2017 Aug;22(8):1–7. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.22.8.086009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Halicek M, Little JV, Wang X, Chen AY, Fei B. Optical biopsy of head and neck cancer using hyperspectral imaging and convolutional neural networks. J Biomed Opt. 2019 Mar;24(3):1–9. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.24.3.036007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang L, Wu Y, Zheng B, Su L, Chen Y, Ma S, et al. Rapid histology of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma with deep-learning based stimulated Raman scattering microscopy. Theranostics. 2019 Apr;9(9):2541–54. doi: 10.7150/thno.32655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Halicek M, Little JV, Wang X, Patel M, Griffith CC, Chen AY, et al. Tumor margin classification of head and neck cancer using hyperspectral imaging and convolutional neural networks. Proc SPIE Int Soc Opt Eng. 2018 Feb;10576:1057605. doi: 10.1117/12.2293167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Daniels K, Gummadi S, Zhu Z, Wang S, Patel J, Swendseid B, et al. Machine learning by ultrasonography for genetic risk stratification of thyroid nodules. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Oct;146(1):1–6. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parmar P, Habib AR, Mendis D, Daniel A, Duvnjak M, Ho J, et al. An artificial intelligence algorithm that identifies middle turbinate pneumatisation (concha bullosa) on sinus computed tomography scans. J Laryngol Otol. 2020 Apr;134(4):328–31. doi: 10.1017/S0022215120000444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Murata M, Ariji Y, Ohashi Y, Kawai T, Fukuda M, Funakoshi T, et al. Deep-learning classification using convolutional neural network for evaluation of maxillary sinusitis on panoramic radiography. Oral Radiol. 2019 Sep;35(3):301–7. doi: 10.1007/s11282-018-0363-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lai YH, Tsao Y, Lu X, Chen F, Su YT, Chen KC, et al. Deep learning-based noise reduction approach to improve speech intelligibility for cochlear implant recipients. Ear Hear. 2018 Jul-Aug;39(4):795–809. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Healy EW, Yoho SE, Chen J, Wang Y, Wang D. An algorithm to increase speech intelligibility for hearing-impaired listeners in novel segments of the same noise type. J Acoust Soc Am. 2015 Sep;138(3):1660–9. doi: 10.1121/1.4929493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Erfanian Saeedi N, Blamey PJ, Burkitt AN, Grayden DB. An integrated model of pitch perception incorporating place and temporal pitch codes with application to cochlear implant research. Hear Res. 2017 Feb;344:135–47. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guerra-Jimenez G, Ramos De Miguel A, Falcon Gonzalez JC, Borkoski Barreiro SA, Perez Plasencia D, Ramos Macias A. Cochlear implant evaluation: prognosis estimation by data mining system. J Int Adv Otol. 2016 Apr;12(1):1–7. doi: 10.5152/iao.2016.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lai YH, Chen F, Wang SS, Lu X, Tsao Y, Lee CH. A deep denoising autoencoder approach to improving the intelligibility of vocoded speech in cochlear implant simulation. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2017 Jul;64(7):1568–78. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2016.2613960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen J, Wang Y, Yoho SE, Wang D, Healy EW. Large-scale training to increase speech intelligibility for hearing-impaired listeners in novel noises. J Acoust Soc Am. 2016 May;139(5):2604. doi: 10.1121/1.4948445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gao X, Grayden DB, McDonnell MD. Modeling electrode place discrimination in cochlear implant stimulation. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2017 Sep;64(9):2219–29. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2016.2634461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hajiaghababa F, Marateb HR, Kermani S. The design and validation of a hybrid digital-signal-processing plug-in for traditional cochlear implant speech processors. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2018 Jun;159:103–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ramos-Miguel A, Perez-Zaballos T, Perez D, Falconb JC, Ramosb A. Use of data mining to predict significant factors and benefits of bilateral cochlear implantation. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015 Nov;272(11):3157–62. doi: 10.1007/s00405-014-3337-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Powell ME, Rodriguez Cancio M, Young D, Nock W, Abdelmessih B, Zeller A, et al. Decoding phonation with artificial intelligence (DeP AI): proof of concept. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2019 Mar;4(3):328–34. doi: 10.1002/lio2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tsui SY, Tsao Y, Lin CW, Fang SH, Lin FC, Wang CT. Demographic and symptomatic features of voice disorders and their potential application in classification using machine learning algorithms. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2018;70(3-4):174–82. doi: 10.1159/000492327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fang SH, Tsao Y, Hsiao MJ, Chen JY, Lai YH, Lin FC, et al. Detection of pathological voice using cepstrum vectors: a deep learning approach. J Voice. 2019 Sep;33(5):634–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fujimura S, Kojima T, Okanoue Y, Shoji K, Inoue M, Hori R. Discrimination of “hot potato voice” caused by upper airway obstruction utilizing a support vector machine. Laryngoscope. 2019 Jun;129(6):1301–7. doi: 10.1002/lary.27584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rameau A. Pilot study for a novel and personalized voice restoration device for patients with laryngectomy. Head Neck. 2020 May;42(5):839–45. doi: 10.1002/hed.26057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang L, Fabbri D, Upender R, Kent D. Automated sleep stage scoring of the Sleep Heart Health Study using deep neural networks. Sleep. 2019 Oct;42(11):zsz159. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang X, Xu M, Li Y, Su M, Xu Z, Wang C, et al. Automated multi-model deep neural network for sleep stage scoring with unfiltered clinical data. Sleep Breath. 2020 Jun;24(2):581–90. doi: 10.1007/s11325-019-02008-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang L, Wu H, Zhang X, Wei X, Hou F, Ma Y. Sleep heart rate variability assists the automatic prediction of long-term cardiovascular outcomes. Sleep Med. 2020 Mar;67:217–24. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.11.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yao J, Zhang YT. The application of bionic wavelet transform to speech signal processing in cochlear implants using neural network simulations. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2002 Nov;49(11):1299–309. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2002.804590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nemati P, Imani M, Farahmandghavi F, Mirzadeh H, Marzban-Rad E, Nasrabadi AM. Artificial neural networks for bilateral prediction of formulation parameters and drug release profiles from cochlear implant coatings fabricated as porous monolithic devices based on silicone rubber. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2014 May;66(5):624–38. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Middlebrooks JC, Bierer JA. Auditory cortical images of cochlear-implant stimuli: coding of stimulus channel and current level. J Neurophysiol. 2002 Jan;87(1):493–507. doi: 10.1152/jn.00211.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Charasse B, Thai-Van H, Chanal JM, Berger-Vachon C, Collet L. Automatic analysis of auditory nerve electrically evoked compound action potential with an artificial neural network. Artif Intell Med. 2004 Jul;31(3):221–9. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Botros A, van Dijk B, Killian M. AutoNR: an automated system that measures ECAP thresholds with the Nucleus Freedom cochlear implant via machine intelligence. Artif Intell Med. 2007 May;40(1):15–28. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.van Dijk B, Botros AM, Battmer RD, Begall K, Dillier N, Hey M, et al. Clinical results of AutoNRT, a completely automatic ECAP recording system for cochlear implants. Ear Hear. 2007 Aug;28(4):558–70. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31806dc1d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gartner L, Lenarz T, Joseph G, Buchner A. Clinical use of a system for the automated recording and analysis of electrically evoked compound action potentials (ECAPs) in cochlear implant patients. Acta Otolaryngol. 2010 Jun;130(6):724–32. doi: 10.3109/00016480903380539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nemati P, Imani M, Farahmandghavi F, Mirzadeh H, Marzban-Rad E, Nasrabadi AM. Dexamethasone-releasing cochlear implant coatings: application of artificial neural networks for modelling of formulation parameters and drug release profile. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2013 Aug;65(8):1145–57. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang J, Wei W, Ding J, Roland JT, Jr, Manolidis S, Simaan N. Inroads toward robot-assisted cochlear implant surgery using steerable electrode arrays. Otol Neurotol. 2010 Oct;31(8):1199–206. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181e7117e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chang CH, Anderson GT, Loizou PC. A neural network model for optimizing vowel recognition by cochlear implant listeners. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2001 Mar;9(1):42–8. doi: 10.1109/7333.918275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Castaneda-Villa N, James CJ. Objective source selection in blind source separation of AEPs in children with cochlear implants. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2007;2007:6224–7. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2007.4353777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Desmond JM, Collins LM, Throckmorton CS. Using channel-specific statistical models to detect reverberation in cochlear implant stimuli. J Acoust Soc Am. 2013 Aug;134(2):1112–20. doi: 10.1121/1.4812273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kim JW, Kim T, Shin J, Lee K, Choi S, Cho SW. Prediction of apnea-hypopnea index using sound data collected by a noncontact device. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020 Mar;162(3):392–9. doi: 10.1177/0194599819900014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ruiz EM, Niu T, Zerfaoui M, Kunnimalaiyaan M, Friedlander PL, Abdel-Mageed AB, et al. A novel gene panel for prediction of lymphnode metastasis and recurrence in patients with thyroid cancer. Surgery. 2020 Jan;167(1):73–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2019.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhong Q, Fang J, Huang Z, Yang Y, Lian M, Liu H, et al. A response prediction model for taxane, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy in hypopharyngeal carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2018 Aug;8(1):12675. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31027-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chowdhury NI, Li P, Chandra RK, Turner JH. Baseline mucus cytokines predict 22-item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test results after endoscopic sinus surgery. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020 Jan;10(1):15–22. doi: 10.1002/alr.22449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Urata S, Iida T, Yamamoto M, Mizushima Y, Fujimoto C, Matsumoto Y, et al. Cellular cartography of the organ of Corti based on optical tissue clearing and machine learning. Elife. 2019 Jan;8:e40946. doi: 10.7554/eLife.40946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhao Z, Li Y, Wu Y, Chen R. Deep learning-based model for predicting progression in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 2020;27(1):19–28. doi: 10.3233/CBM-190380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Essers PBM, van der Heijden M, Verhagen CV, Ploeg EM, de Roest RH, Leemans CR, et al. Drug sensitivity prediction models reveal a link between DNA repair defects and poor prognosis in HNSCC. Cancer Res. 2019 Nov;79(21):5597–611. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ishii H, Saitoh M, Sakamoto K, Sakamoto K, Saigusa D, Kasai H, et al. Lipidome-based rapid diagnosis with machine learning for detection of TGF-β signalling activated area in head and neck cancer. Br J Cancer. 2020 Mar;122(7):995–1004. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-0732-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Patel KN, Angell TE, Babiarz J, Barth NM, Blevins T, Duh QY, et al. Performance of a genomic sequencing classifier for the preoperative diagnosis of cytologically indeterminate thyroid nodules. JAMA Surg. 2018 Sep;153(9):817–24. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stepp WH, Farquhar D, Sheth S, Mazul A, Mamdani M, Hackman TG, et al. RNA oncoimmune phenotyping of HPV-positive p16-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas by nodal status. Version 2. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018 Nov;144(11):967–75. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.0602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shew M, New J, Wichova H, Koestler DC, Staecker H. Using machine learning to predict sensorineural hearing loss based on perilymph micro RNA expression profile. Sci Rep. 2019 Mar;9(1):3393. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40192-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nam Y, Choo OS, Lee YR, Choung YH, Shin H. Cascade recurring deep networks for audible range prediction. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2017 May;17(Suppl 1):56. doi: 10.1186/s12911-017-0452-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kim H, Kang WS, Park HJ, Lee JY, Park JW, Kim Y, et al. Cochlear implantation in postlingually deaf adults is time-sensitive towards positive outcome: prediction using advanced machine learning techniques. Sci Rep. 2018 Dec;8(1):18004. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36404-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bing D, Ying J, Miao J, Lan L, Wang D, Zhao L, et al. Predicting the hearing outcome in sudden sensorineural hearing loss via machine learning models. Clin Otolaryngol. 2018 Jun;43(3):868–74. doi: 10.1111/coa.13068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lau K, Wilkinson J, Moorthy R. A web-based prediction score for head and neck cancer referrals. Clin Otolaryngol. 2018 Mar;43(4):1043–9. doi: 10.1111/coa.13098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wilson MB, Ali SA, Kovatch KJ, Smith JD, Hoff PT. Machine learning diagnosis of peritonsillar abscess. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Nov;161(5):796–9. doi: 10.1177/0194599819868178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Priesol AJ, Cao M, Brodley CE, Lewis RF. Clinical vestibular testing assessed with machine-learning algorithms. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015 Apr;141(4):364–72. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.3519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chan J, Raju S, Nandakumar R, Bly R, Gollakota S. Detecting middle ear fluid using smartphones. Sci Transl Med. 2019 May;11(492):eaav1102. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Karadaghy OA, Shew M, New J, Bur AM. Development and assessment of a machine learning model to help predict survival among patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 May;145(12):1115–20. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mermod M, Jourdan EF, Gupta R, Bongiovanni M, Tolstonog G, Simon C, et al. Development and validation of a multivariable prediction model for the identification of occult lymph node metastasis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2020 Aug;42(8):1811–20. doi: 10.1002/hed.26105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Formeister EJ, Baum R, Knott PD, Seth R, Ha P, Ryan W, et al. Machine learning for predicting complications in head and neck microvascular free tissue transfer. Laryngoscope. 2020 Jan 28; doi: 10.1002/lary.28508. [Epub]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Shew M, New J, Bur AM. Machine learning to predict delays in adjuvant radiation following surgery for head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Jun;160(6):1058–64. doi: 10.1177/0194599818823200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bur AM, Holcomb A, Goodwin S, Woodroof J, Karadaghy O, Shnayder Y, et al. Machine learning to predict occult nodal metastasis in early oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2019 May;92:20–5. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kamogashira T, Fujimoto C, Kinoshita M, Kikkawa Y, Yamasoba T, Iwasaki S. Prediction of vestibular dysfunction by applying machine learning algorithms to postural instability. Front Neurol. 2020 Feb;11:7. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Liu YW, Kao SL, Wu HT, Liu TC, Fang TY, Wang PC. Transient-evoked otoacoustic emission signals predicting outcomes of acute sensorineural hearing loss in patients with Meniere’s disease. Acta Otolaryngol. 2020 Mar;140(3):230–5. doi: 10.1080/00016489.2019.1704865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Luo J, Erbe C, Friedland DR. Unique clinical language patterns among expert vestibular providers can predict vestibular diagnoses. Otol Neurotol. 2018 Oct;39(9):1163–71. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wu Q, Chen J, Deng H, Ren Y, Sun Y, Wang W, et al. Expert-level diagnosis of nasal polyps using deep learning on whole-slide imaging. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020 Feb;145(2):698–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Jabez Christopher J, Khanna Nehemiah H, Kannan A. A clinical decision support system for diagnosis of allergic rhinitis based on intradermal skin tests. Comput Biol Med. 2015 Oct;65:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2015.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Adnane C, Adouly T, Khallouk A, Rouadi S, Abada R, Roubal M, et al. Using preoperative unsupervised cluster analysis of chronic rhinosinusitis to inform patient decision and endoscopic sinus surgery outcome. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017 Feb;274(2):879–85. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-4315-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Soler ZM, Hyer JM, Rudmik L, Ramakrishnan V, Smith TL, Schlosser RJ. Cluster analysis and prediction of treatment outcomes for chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Apr;137(4):1054–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Soler ZM, Hyer JM, Ramakrishnan V, Smith TL, Mace J, Rudmik L, et al. Identification of chronic rhinosinusitis phenotypes using cluster analysis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015 May;5(5):399–407. doi: 10.1002/alr.21496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Divekar R, Patel N, Jin J, Hagan J, Rank M, Lal D, et al. Symptom-based clustering in chronic rhinosinusitis relates to history of aspirin sensitivity and postsurgical outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015 Nov-Dec;3(6):934–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2015.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lal D, Hopkins C, Divekar RD. SNOT-22-based clusters in chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyposis exhibit distinct endotypic and prognostic differences. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018 Jul;8(7):797–805. doi: 10.1002/alr.22101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Tomassen P, Vandeplas G, Van Zele T, Cardell LO, Arebro J, Olze H, et al. Inflammatory endotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis based on cluster analysis of biomarkers. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 May;137(5):1449–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kim JW, Huh G, Rhee CS, Lee CH, Lee J, Chung JH, et al. Unsupervised cluster analysis of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyp using routinely available clinical markers and its implication in treatment outcomes. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019 Jan;9(1):79–86. doi: 10.1002/alr.22221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Goldstein CA, Berry RB, Kent DT, Kristo DA, Seixas AA, Redline S, et al. Artificial intelligence in sleep medicine: background and implications for clinicians. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020 Apr;16(4):609–18. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Weininger O, Warnecke A, Lesinski-Schiedat A, Lenarz T, Stolle S. Computational analysis based on audioprofiles: a new possibility for patient stratification in office-based otology. Audiol Res. 2019 Nov;9(2):230. doi: 10.4081/audiores.2019.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Barbour DL, Howard RT, Song XD, Metzger N, Sukesan KA, DiLorenzo JC, et al. Online machine learning audiometry. Ear Hear. 2019 Jul-Aug;40(918):26. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wu YH, Ho HC, Hsiao SH, Brummet RB, Chipara O. Predicting three-month and 12-month post-fitting real-world hearing-aid outcome using pre-fitting acceptable noise level (ANL) Int J Audiol. 2016;55(5):285–94. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2015.1120892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bramhall NF, McMillan GP, Kujawa SG, Konrad-Martin D. Use of non-invasive measures to predict cochlear synapse counts. Hear Res. 2018 Dec;370:113–9. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Rasku J, Pyykko I, Levo H, Kentala E, Manchaiah V. Disease profiling for computerized peer support of Meniere’s disease. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol. 2015 Sep;2(2):e9. doi: 10.2196/rehab.4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Morse JC, Shilts MH, Ely KA, Li P, Sheng Q, Huang LC, et al. Patterns of olfactory dysfunction in chronic rhinosinusitis identified by hierarchical cluster analysis and machine learning algorithms. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019 Mar;9(3):255–64. doi: 10.1002/alr.22249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Quon H, Hui X, Cheng Z, Robertson S, Peng L, Bowers M, et al. Quantitative evaluation of head and neck cancer treatment-related dysphagia in the development of a personalized treatment deintensification paradigm. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017 Dec;99(5):1271–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Jochems A, Leijenaar RT, Bogowicz M, Hoebers FJ, Wesseling F, Huang SH, et al. Combining deep learning and radiomics to predict HPV status in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Radiat Oncol. 2018 Apr;127:S504–5. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Bao T, Klatt BN, Whitney SL, Sienko KH, Wiens J. Automatically evaluating balance: a machine learning approach. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2019 Feb;27(2):179–86. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2019.2891000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]