Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has penetrated our daily lives, leading us to a new normal era. The unexpected impact of COVID-19 has posed a unique challenge for the health care system, bringing innovation around the world. Considering the current pandemic pattern, comprehensive preparedness strategies of healthcare resources need to be implemented to prepare for a large resurgence of COVID-19 within a short time. With the unprecedented spread of the new pandemic and the impending influenza season, scientific evidence-based schemes need to be developed through cooperation, coordination, and solidarity. Based on the early experience with the current pandemic, this narrative interpretive review of qualitative studies suggests a 6-domain plan to establish a better health care system that is prepared to deal with the current and future public health crises. The 6 domains are medical institutions, medical workforce, medical equipment, COVID-19 surveillance, data and information application, and governance structure.

Keywords: COVID-19, Healthcare Crisis Resource Management, Healthcare Systems, Pandemic, Health Resources

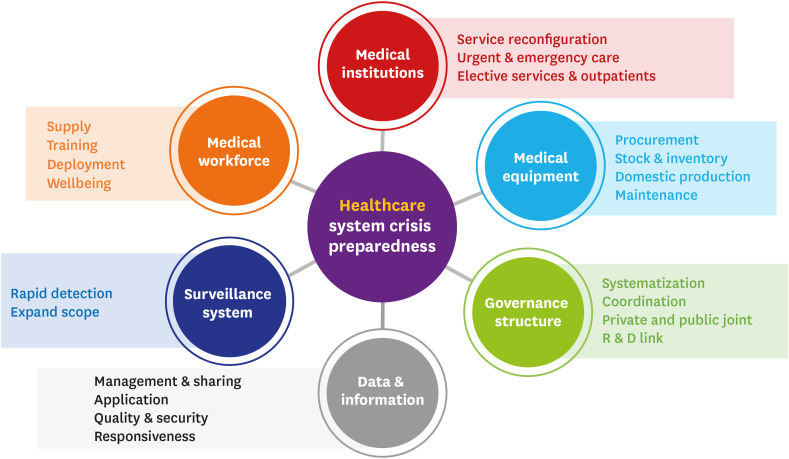

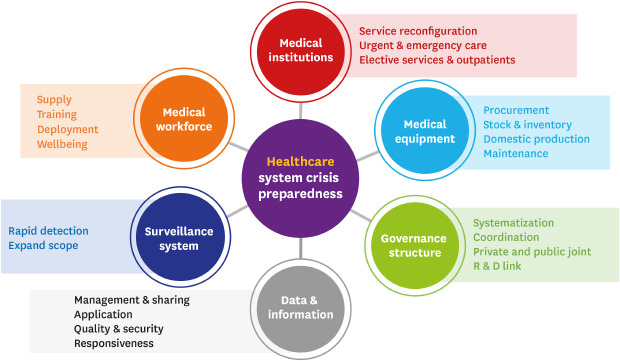

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) presents an unparalleled challenge to the healthcare system. Already, in some countries, the exponential surge of COVID-19 cases during the beginning of the outbreak threatened to collapse the healthcare system.1,2,3 A well-functioning healthcare system, which combines physicians, hospitals, and medical resources, provides the complete spectrum of medical care for targeted populations and meets the their healthcare needs.4 However, even while tackling the local or regional COVID-19 epidemic, hospitals have struggled to overcome significant resource strain, leading to excess mortality, unsecured wellbeing of medical staff, and amplified social anxiety.3,5,6

For centuries, several major pandemics have harmed people in multiple waves.7 The second wave of the Spanish flu that occurred in the early 20th century is said to have been more deadly than the first wave, and it subsequently continued to proceed at a devastating speed. Ultimately 50 to 100 million people were killed globally in few months.8 Like the Asian flu and Hong Kong flu, with 2009 H1N1 swine flu pandemic, the number of cases seemed to decline at the beginning of summer and it then increased rapidly in the fall.7 Although the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus is biologically different from the influenza virus, we must be prepared for the prolongation of this pandemic and the next wave.

In the absence of therapeutic options and vaccines against COVID-19, the high global transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 and the sheer number of asymptomatic infections leaves us out of hope for eradication. People have no immunity to the novel virus, which has already successfully spread in many climates. In addition, many countries, including the Republic of Korea (ROK), have to face COVID-19 during the impending influenza season.

The COVID-19 pandemic may have slowed down in many parts of the country, but many experts have warned about an inevitable large resurgence of COVID-19 nationally, with local or regional epidemics in the fall and winter of 2020. Further, local increases in cases have been reported in some countries following the easing of lockdown policies. To prevent this surge of cases from exceeding our current preparedness capabilities, multifaceted pandemic countermeasures should continue to be applied in outbreak situations. While efforts to flatten the curve of outbreaks would continue, the capacity of healthcare resources need to be increased simultaneously.

Therefore, this article aims to derive suggestions for short-, mid-, and long-term strategies for medical resource management beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, which would help us cope with the public health crisis caused by another surge in COVID-19 cases. This paper outlines a well-organized approach to a proactive preparedness and response to the resurge of COVID-19 cases based on six key domains (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Domains of comprehensive healthcare system preparedness for a large resurgence of COVID-19.

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

METHODS

Overview

The framework for conducting a structured, systematic narrative review followed a previously known methodology that identifies disseminated research findings and comprehends the synthesis of qualitative study-derived results from the existing literature.9,10 This protocol included identifying research questions, subdividing the research topic into domains, determining specific key terms for the search strategy, extracting references, reviewing and selecting articles, summarizing and synthesizing information, and organizing study findings. The role of experts was important because this topic area was not well organized based on scientific evidence.

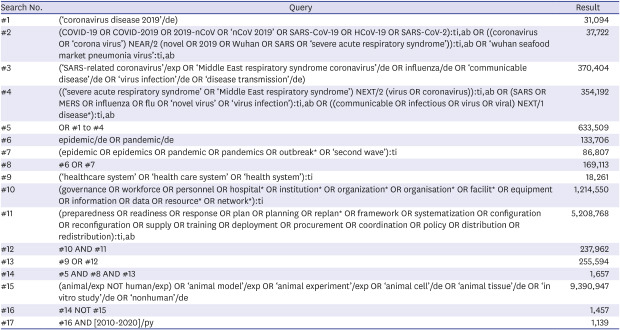

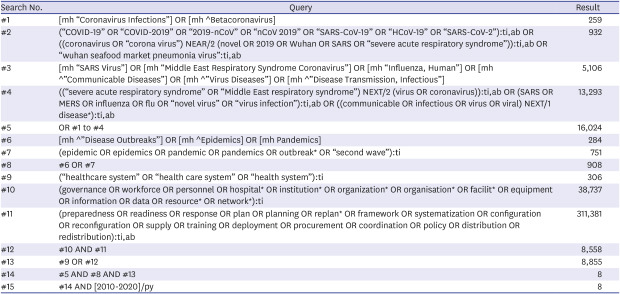

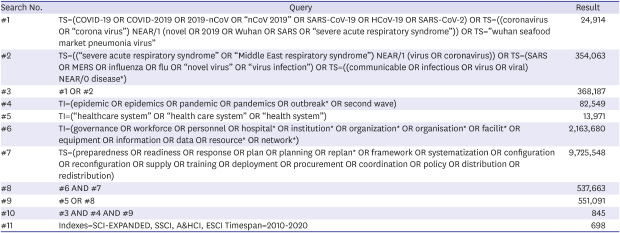

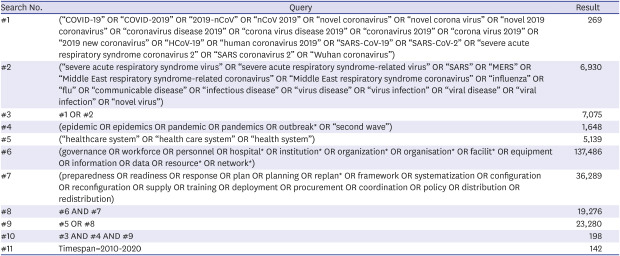

Search strategy

A comprehensive search of the literature was undertaken initially on July 31, 2020. Electronic databases, including PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and KoreaMed, were searched for articles published in English, on the pandemic-preparedness strategies of healthcare resources. To focus on the most current research, database searches were limited to the past 10 years (2010–2020). The search terms were suggested by experts of infectious diseases, with the assistance of a research librarian. Subject headings and keyword terms were chosen under the three broad search themes of infectious diseases, epidemic or pandemic, and healthcare system. We also used variants and combinations of the search terms. The reference lists of the included articles were scrutinized to identify additional relevant studies that were not discovered during the database searches. Only studies involving humans were included in this systematic review. The full list of search terms and a detailed description of the complete search strategies have been provided in Appendix 1.

Eligibility criteria and selection of articles

Our research included all types of literature if they aimed to suggest a detailed methodology to develop preparedness strategies of healthcare resources for epidemics or pandemics. Publications that did not explicitly suggest how to prepare or respond to the health public crisis with regard to the healthcare system, including medical institutions, workforce, medical resources or supplies, governance, and information sharing, were excluded from this analysis. As a preliminary step, the title and abstract of the articles identified in the initial search were screened and evaluated based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and duplicate publications were removed. The second stage involved reviewing the full text of potentially-relevant publications for inclusion. In the last stage, the reference lists of the ultimately selected publications were hand-searched for additional articles relevant to this review.

Data charting

To map the available evidence, data extracted from the final included articles were tabulated, including publication year, publication type, domain focus, and narratively suggested intervention. Each article was reviewed to identify which of the 6 predefined domains it fit; they were then used as data for the narrative review.

RESULTS

Results of the search

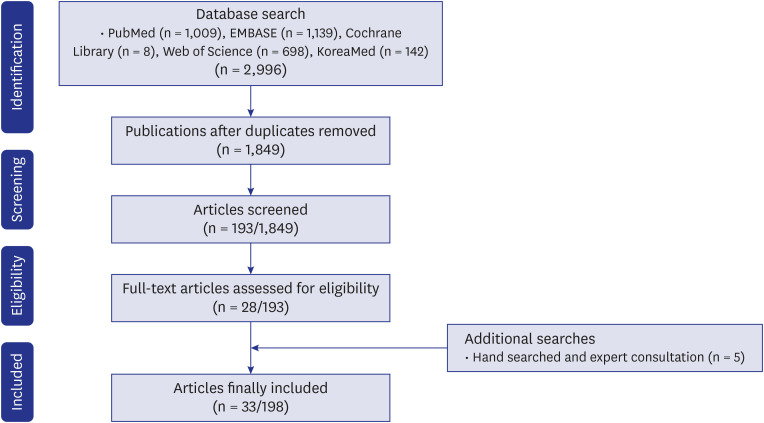

A total of 2,996 eligible articles were identified through initial searches, of which, 1,147 articles were excluded due to duplication and 1,656 were excluded because the contents in the title and abstract were not relevant for this review. The remaining 193 studies were screened again using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Subsequently, 165 articles were removed after a full-text review. Finally, 28 articles met the criteria for inclusion for this review. An additional five articles that were not detected by the database search were found from the reference lists of selected articles using manual search. The selection process for this study has been presented in shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Flow diagram of the literature selection process for the systematic narrative review.

Systematic review findings

Describing approaches falling under six predefined domains, 33 articles specifically focused on preparedness strategies of healthcare resources for the pandemic (Table 1).11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43 The final list of selected publications included 3 original articles, 9 commentaries, and 21 review articles. All but six articles were published between 2019 and 2020. The six domains of approaches conceived by experts were mostly based on subjective opinions. As several studies included in the present systematic review did not provide detailed information, they were not grouped by these predefined domains. Although several review articles dealt with more than one response strategy for the pandemic, they were grouped based on the most salient domain.

Table 1. Overview of evidence from the systematic review on preparedness strategies for a large resurgence of COVID-19 nationally.

| Domain | Year | Publication type | Core suggestions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical institutions | 2020 | Review article | • Adaptive model of health system organization and responses | 11 |

| • Mobilization of different stakeholders and communities | ||||

| • Synchronous implementation of response strategies | ||||

| 2020 | Review article | • Critical care and peri-operative healthcare resource management strategies | 12 | |

| 2020 | Review article | • Collaborative model for an academic hospital and long-term care facilities | 13 | |

| 2020 | Commentary | • Health system collaborations for supporting nursing facilities | 14 | |

| 2020 | Review article | • Improving preparedness for and response to COVID-19 in long-term care hospitals | 15 | |

| 2020 | Review article | • Designated hospitals, newly built temporary hospitals, and Fangcang shelter hospitals | 16 | |

| 2020 | Commentary | • Strategies for safe hospital operations based on the experiences of the Republic of Korea | 17 | |

| 2020 | Review article | • Role of primary care in the healthcare system for fighting COVID-19 | 18 | |

| 2020 | Review article | • National plan for building negative pressure isolation rooms | 19 | |

| 2020 | Commentary | • Strategical preparedness and response actions in the healthcare system against COVID-2019 according to the transmission scenario | 20 | |

| 2016 | Review article | • Continuous and integrated chain of activities that link hospitals, health centers, and communities | 21 | |

| Medical workforce | 2020 | Commentary | • A hidden key to COVID-19 management: public health doctors | 22 |

| 2020 | Review article | • Training content, including self-protection knowledge and skills, professional knowledge and skills, and preventive psychology counseling based on national policies and guidelines | 23 | |

| 2020 | Review article | • Multidisciplinary teams and new online training tools | 24 | |

| • Nationwide centralized recruitment strategy, streamlined process to quickly communicate recruiting information across departments and expedite onboarding to areas of greatest need | ||||

| 2020 | Commentary | • Provision of well-trained healthcare workers | 25 | |

| 2019 | Original article | • Strengthening healthcare workforce capacity: an innovative and effective approach to epidemic preparedness and response | 26 | |

| Medical equipment | 2020 | Review article | • National strategy for ventilator and ICU resource allocation during the COVID-19 pandemic | 27 |

| 2020 | Review article | • Allocation of scarce resources in a pandemic | 28 | |

| 2020 | Review article | • Fair allocation of scarce medical resources | 29 | |

| 2020 | Commentary | • Methods to address critical supply shortages, including directing private-sector companies to manufacture more PPE, reducing hoarding of PPE, and ensuring reasonable distribution of PPE | 30 | |

| 2020 | Review article | • Strategies to inform allocation of stockpiled ventilators to healthcare facilities during a pandemic | 31 | |

| 2020 | Commentary | • Activation of the materials R&D community | 32 | |

| COVID-19 surveillance | 2020 | Review article | • Notifiable infectious diseases reporting information system | 33 |

| • Strong and coordinated laboratory infrastructure throughout the country | ||||

| 2020 | Original article | • Dedicated enhanced surveillance for high-risk groups using space-time surveillance | 34 | |

| 2016 | Review article | • Building capacities for early event detection, epidemiologic workforce, and laboratory response | 35 | |

| Data and information application | 2020 | Commentary | • Applications of digital technology in COVID-19 pandemic planning and response | 36 |

| 2017 | Review article | • Establishing a public agency that has linkages with multiple organizations | 37 | |

| • Institutional collective action framework | ||||

| 2012 | Review article | • Various channels of networks | 38 | |

| • Evidence in the public administration and organization | ||||

| Governance structure | 2020 | Review article | • Consolidated and evidence-based nation-wide plan | 39 |

| • Community participation and engagement in the response to COVID-19 | ||||

| 2020 | Review article | • Whole-of-government response and accountability | 40 | |

| • Multi-sectoral cooperation platform | ||||

| 2019 | Review article | • National/subnational leadership and coordination | 41 | |

| • Partnership and coordination between government and non-government organizations | ||||

| • Global health leadership | ||||

| 2014 | Original article | • Rational scientific approach to pandemic management with global forces and new intermodal forms of nodal governance | 42 | |

| • Socio-politically nuanced response to the challenges of pandemic management | ||||

| 2013 | Review article | • Comprehensive national agency to deal with public health crisis | 43 |

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019, ICU = intensive care unit, PPE = personal protective equipment.

DISCUSSION

Medical institutions

The most important measures implemented globally in response to COVID-19 pertained to restricting transmission and protecting health systems. Accurate and rapid diagnosis, effective isolation of cases, and comprehensive contact tracing and quarantining of contacts restrained the spread of COVID-19 such that it was prevented from crossing the threshold at which health systems would be unable to deliver quality clinical care.44 Though the COVID-19 outbreak is prolonged, rapid case identification and multifaceted surveillance strategies should continue to be strengthened.

During this pandemic, frontline healthcare workers (HCWs) are treating not only the COVID-19 cases but also non-COVID-19 cases. Some experts suggested that the measures against COVID-19 may negatively impact other causes of death, owing to a reduction of hospital visits and emergency admissions.45 COVID-19 screening should be conducted actively, mainly in public health centers and medical institutions, so that medical care of non-COVID-19 patients would be normalized immediately, particularly in tertiary care hospitals. Services such as the acute respiratory infection clinics (ARICs) operated in Singapore should also be established immediately through public–private cooperation, such that private institutions, including primary care clinics, would be able to function in a safe setting.46 ARICs are expected to conduct testing for COVID-19 and to treat patients with acute respiratory infection together. This would create a safe care environment and would simultaneously facilitate active surveillance of COVID-19 in the community.18,21 The drive-through and walk-through screening systems for COVID-19 testing should be conducted appropriately based on the dynamic situation.47,48

During early strategic planning, a control tower must first identify the current state of beds available in the hospital to aid case management. This process should utilize modeling data according to the changing situation to enable the estimation of and preparation for the potential shortage of intensive care unit (ICU) beds, non-ICU beds, and negative-pressure or air-borne infection isolation rooms (AIIRs).19 In Korea, public hospitals and the National Medical Center have been designated for COVID-19 care since the early phase of the COVID-19 response. Government-designated public hospitals and the National Medical Center should be dedicated to treating COVID-19 patients with asymptomatic infection or mild illness, and those with critical-illness, respectively, to ensure the efficiency of medical care. All national designated AIIRs that have been set up since 2003 should be evaluated to determine if such beds are available for actual cases.43 If a substantial surge occurs, temporary care facilities can be set up to exclusively treat COVID-19 patients with asymptomatic infection or mild illness, or for those in the recovery phase.16,49 In preparation for a surge beyond the care-provision capacity of facilities, non-designated private academic and teaching hospitals should be equipped and trained to care for COVID-19 cases.11,17,20

In order for prepared beds, especially ICU beds, to be used smoothly, it is important to establish systematic and rational severity criteria for the triage and transfer of COVID-19 cases. In addition to such step-up transfer protocols for severe patients, it is essential to develop step-down transfer protocol for recovery patients. For the rapid bed circulation of severe patients, it may be beneficial to provide medical facilities for long-term care and post-acute care for COVID-19 patients with dementia, mental illness, medically complex conditions, and disability requiring hospital-level intense medical rehabilitation.15,50

From the long-term perspective, it is essential to develop and implement a plan to establish national infectious disease hospitals in all regions of the country.51 In this model, specialized units for intensive care, elective or emergent surgery, delivery, and pediatric care should be typically equipped with the infrastructure necessary for treating patients with emerging infectious diseases.12 The government may create a new independent medical institution, but the efficiency of medical resources can be improved by linking them with existing academic or tertiary hospitals and by ensuring flexible operation depending on the situation. A collaborative model for academic hospitals and long-term care facilities would enable healthcare facilities to meet the real-time facility needs for the containment of the pandemic.13,14 However, in order to maintain such a realistic medical system, appropriate institutional support and compensation systems must be guaranteed.

Medical workforce

A skilled, healthy, and well-trained medical workforce constitutes the backbone of any healthcare system, and personnel training is essential to ensure successful preparedness. Physicians, nurses, caregivers, paramedics, and other hospital staff around the world are facing an unprecedented workload in health facilities that have been overstretched during the pandemic. Public health authorities and each hospital's control tower need to be proactively prepared to expand the supply of personnel.24 In the short term, alternative sources of staff recruitment include those who have retired recently, returners from non-clinical settings such as research and education, healthcare students, and volunteers. In the long term, the government should develop a system to train competent human resources as medical professionals for the pandemic, including infectious disease specialists, intensive care physicians, intensive care nurses, infection control professionals, and epidemiologists.22

Apart from the epidemic situation, HCWs are always at risk of nosocomial transmission of COVID-19, with infected HCWs accounting for 2.7%–3.8% of confirmed cases.52,53 In contrast, a study showed that no HCW was infected when they received training on the appropriate use of personal protective equipment (PPE).54 The safety of HCWs should be the first priority.23 Therefore, all medical and non-medical personnel must be sufficiently trained for the proper use of PPE or a powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR).26 After providing adequate PPE or PAPR training, HCWs providing specialized care should practice using all medical equipment in a high-fidelity simulation environment, which will prepare them to perform expected activities while wearing PPE or a PAPR.25 Finally, scientific evidence on the use of PPE by medical staff at different levels should be studied according to the risk of transmission.

As part of strengthened public health response to the outbreak, a mandatory 14-day stay-home notice was imposed on HCWs who may have come in contact with COVID-19 patients without wearing enhanced PPE. Such measures, including mass isolation after unexpected exposure, can exacerbate the workforce situation by causing sudden staffing shortages. Fortunately, scientific information had been collected about COVID-19 through experience. Rational and scientific response levels must be identified to minimize the shortage of medical resources in the long term, and to prevent medical staff fatigue and economic damage in clinical settings.

As the pandemic situation continues prolong and become more difficult, we expect the role of primary HCWs in the community to gain importance.18,21 With regard to the pandemic, the current healthcare system's primary dependence on public health institutions and tertiary hospitals is insufficient for responding to a surge in patients with acute respiratory diseases during the impending influenza season. In this context, primary physicians comprise the core manpower that could operate ARICs effectively in the community. Therefore, in addition to the active exchange of opinions among stratified medical systems, communication among groups of primary health care providers, experts, and the government are critical to realize the established response strategy effectively. In this regard, a cadre of motivated, trained, and functional community HCWs is expected to play a significant role in the establishment of a public–private partnership system.

Medical equipment

The need for equipment, and medical or non-medical supplies during the COVID-19 pandemic should be gauged in response to changes in the epidemic situation. Public health authorities should list priority equipment and medical or non-medical supplies that are essential for responding to the COVID-19 pandemic, consider alternatives, and develop a tool forecasting their requirements in response to the real-time pandemic using the suite of complimentary surge calculators developed by the World Health Organization.55

The availability of sufficient equipment and medical or non-medical supplies should be monitored in real time by public health authorities. Current stock inventories and forecasted additional demand for equipment and medical or non-medical supplies should be reviewed periodically in response to the changing epidemic situation. The control tower in each hospital should be aware of the stock status of equipment and medical supplies such as PPE or PAPR. If a shortage is identified, public health authorities must strive to secure their stable supply.30,32 In the long run, the government should add the efforts to localize key equipment and medical supplies, including infection control resources such as testing kits, PPE, oxygen delivery systems, closed-circuit ventilators, continuous renal replacement therapy equipment, extracorporeal support systems, infusion devices, and physiological monitors.56

In case of a shortage of resources, a system should be developed to support the decision-making pertaining to the allocation of scarce resources.27,28,31 Previous proposals for the allocation of resources during pandemics converge on four fundamental values; maximizing benefits, treating people equally, promoting and rewarding instrumental value considering benefit to others, and giving priority to the worst off.29 Public health authorities should establish expert committees to develop a national framework that can guide institutions in building equitable and fair decision-making strategies for medical resource allocation.

COVID-19 surveillance: a national framework

Infectious disease surveillance includes the ongoing systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of data on the occurrence of COVID-19, involving the health care delivery system, public health laboratories, and epidemiologists.57,58 It provides a scientific and factual database that is essential for making informed decisions and for implementing appropriate public health action to contain the spread of COVID-19.33,59

Comprehensive national surveillance for COVID-19 allows public health authorities to monitor long-term trends in COVID-19 transmission, understand disease activity at the local and national level, define the burden of COVID-19, identify chances for disease containment, and evaluate the impact of policies.60 Furthermore, surveillance data can be used to plan the allocation of available resources to areas of great necessity, and to forecast future trends in the incidence of COVID-19 using real-world data. Population-level sero-surveillance can provide reliable markers of exposure and prior infection to SARS-CoV-2. Therefore, it is essential to create the capacity to perform widespread serologic testing to identify the true extent of COVID-19, especially in regions where active testing was not performed extensively and asymptomatic or mildly ill patients were likely to be undiagnosed. Surveillance isolates could also be used to create a better understanding of viral evolution, molecular epidemiology, and transmission dynamics.

Surveillance sites for COVID-19 include individuals in the community, primary care sites, other hospitals, existing sentinel influenza-like illness or severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) clinics, residential facilities, and vulnerable groups.60 Individual cases in the community, participation in contact tracing, cluster investigations and sentinel cases, or the virus are subject to surveillance.60

The ROK has already established a case-based surveillance system that relies on reporting from public health centers. Considering the prolongation of this pandemic and the rapid exponential growth of COVID-19 cases in populations, individuals exhibiting the symptoms and signs of COVID-19 should be able to access testing at the primary care level. Another complementary option is to establish dedicated COVID-19 community testing facilities, such as drive-through sites or ARIC-type facilities in community buildings.

Hospitalized surveillance data that include the number and proportion of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 provide information on the COVID-19 burden. As a mandatory notifiable disease, data on patients with confirmed COVID-19 diagnoses in hospitals have also been included, within 24 hours, in an epidemiological analysis of public health authorities. Similar to hospitalized surveillance data, mortality and excess death data have also been included in the metrics of COVID-19 spread in the community.61

Particularly, sentinel surveillance is an active surveillance system that offers high-quality data.62 Selected reporting sites are used to identify trends, notice outbreaks, and monitor the disease burden of COVID-19 in a community. In the ROK, the Korea Influenza and Respiratory Surveillance System and SARI surveillance systems could be used for community- and hospital-based surveillance, respectively. This would enable the monitoring of COVID-19 epidemiology in private primary clinics, and academic or teaching hospitals, respectively.63,64

Further, it is important to conduct dedicated enhanced surveillance for high-risk groups using space-time surveillance, to ensure the prompt detection of cases and active or emerging clusters of COVID-19 at the national level.34 Some high-risk groups exposed to closed environments, including prisons, long-term-care facilities, nursing homes, and dosshouses, and those working in vulnerable settings, including fishing vessels, call centers, and construction sites, may require dedicated enhanced surveillance regularly and proactively if continuing cluster outbreaks occur. Particularly, on being admitted to a nursing home, a surveillance examination of all patients is expected to protect vulnerable people.

Laboratory-based virologic surveillance includes monitoring the incidence of COVID-19 in the community and testing molecular characteristics that analyze the genetic sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 in the hospitals and commercial laboratories.65 The number of positive and negative tests, and positive testing rate could be used to identify asymptomatic people and to evaluate the adequacy of testing. The difference between the total number of tests and the total number of people tested is also useful for tracking multiple tests of an individual over time. Such measures would provide major indicators of disease spread in the community, such as the proportion of cases with unknown source of exposure.

A national approach to COVID-19 surveillance should be standardized using automated electronic reporting. This information must be shared regularly and clearly, and utilized effectively by the public, public health officials, policy decision-makers, and HCWs.34

Data and information application

Data-driven action is required to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of interventions at all phases of this pandemic.38 While the ROK experienced a sharp growth in COVID-19 cases early in the global pandemic, substantial information has been accumulated about SARS-CoV-2. Now we need to reassess if our response to COVID-19 was scientific. Additionally, we need to revisit our situations based on scientific evidence. Successful response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the ROK was characterized by rapid large-scaling testing, adoption of mask wearing and social distancing measures, and active public participation in following recommendations. However, during the initial outbreak, no measure was proposed based on prior and their effectiveness has not been proven scientifically. Furthermore, there was no data estimating the time-varying reproduction number, which should have been shared constantly, even in extreme conditions.66 So far, the government's dataset has failed to include information on the detailed epidemiological characteristics and clinical information of COVID-19 patients. Clinical data, including information on transmission mechanisms and viruses isolated from COVID-19 cases should be formalized quickly and be discussed among private experts. The refined data should be used in the clinical setting and be applied in preparing countermeasures to ensure preparedness and patient care. Such factual and scientific data will help eliminate numerous rumors and conspiracy theories that circulate at local, national, and global levels.67

During this pandemic, the control tower of the state must establish an information network on the real-time nationwide status of the clinical field in response to the public health crisis.37 With regard to the clinical scene in the contingency, the database of the National Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service can be a valuable foundation for building a computerized system that allows medical staff to share information about COVID-19 patients' medical history. In addition to clinical and epidemiologic data, those on the current status of hospital beds, manpower, and medical equipment or supplies should be collected.

In addition, public health authorities are encouraged to build a data warehouse that can share clinical data on patient progress in real-time during the medical treatment process. Such measures would support operation personnel and improve information utilization. Open and transparent sharing of data with public health authorities, scientists, public health experts, and the public will strengthen pandemic control measures and help in building a bottom-up consensus. It would offer the wider scientific community an opportunity to offer constructive criticism on policies and perhaps suggest course corrections.

In order to provide a basis for the establishment of a policy for preparedness and response to the pandemic, it is necessary to expand the scope of governance and the roadmap for research and development, which is currently too focused on vaccine and drug development. Intensive global collaborative research will also help maximize the amount of scientific information obtained, which could be used to overcome COVID-19 and subsequent pandemics. Emergency support measures for clinical research should be enacted during the surge of cases, including funding research and establishing a fast-track research approval system.

With no effective vaccine or therapy and the rapid transmission of COVID-19, government-coordinated efforts across the globe have focused on containment and mitigation using surveillance, testing, contact tracing, and strict quarantine. Digital technology has been integrated into the pandemic policy and response to control the spread of COVID-19.36 However, digital health interventions, particularly those that track individuals and enforce quarantining, could infringe privacy, data security, and civil liberties. In order to minimize such collateral damage, the scope and duration of personal information sharing should be minimized, with ethical considerations guiding the use of digital proximity tracking technologies.

Governance structure

During the public health crisis, central-local cooperative governance should be created for developing an integrated and coordinated approach based on the regional centered healthcare system.41,43 A decentralized healthcare system is favorable even in case of simultaneous local or regional epidemics. Subnational governments composed of regions and municipalities should be responsible for critical aspects of containment measures and health care, placing them at the frontline of crisis management. As such responsibilities are shared among multiple levels of the government, coordinated effort is critical.40 Particularly, the centralized control tower should be established to link public health authorities to minimize the risk of a fragmented crisis response and to reduce redundant work burden on site, such as repeatedly reporting information to public health centers, city halls, provincial governments, and the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention during the outbreak in the ROK.

National leadership can play a role in coordinating interventions and resource mobilization nationwide only if it is evidence-based.39,42 Under the rational leadership of a national control tower, the mobilization of emergency responses has been forwarded effectively. Multisectoral cooperation at a high level can ensure the appropriate management of healthcare resources across the country.

CONCLUSIONS

To maintain an effective response to the COVID-19 pandemic, public health authorities and hospitals should prepare detailed short- and long-term evidence-based pandemic preparedness plans for the large resurgence of COVID-19 nationally, with local or regional epidemics. This paper suggests a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach to preparedness planning for COVID-19. Such measures will ensure a rational and optimized response from the healthcare system during such difficult times. Indeed, the lessons learned from the crisis will lead us to the way forward in the post-COVID-19 world.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We greatly appreciate the efforts of all hospital employees and their families who are working tirelessly during this outbreak. We thank all the members of the Korean Society of Infectious Diseases (KSID) and members of its task force for Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Appendix 1

Search string applied to the 5 databases, using the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keyword terms for systematic literature review

Database: PubMed (Date: 07/31/2020)

Total hits: 1,009

Database: EMBASE (Date: 07/31/2020)

Total hits: 1,139

Database: Cochrane Library (Date: 07/31/2020)

Total hits: 8

Database: Web of Science (Date: 07/31/2020)

Total hits: 698

Database: KoreaMed (Date: 07/31/2020)

Total hits: 142

Footnotes

Funding: This research was supported by the Government-wide R&D Fund for Infectious Disease Research (GFID), Republic of Korea (Grant No. HG18C0019).

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: Peck KR.

- Data curation: Yoon YK.

- Supervision: Peck KR.

- Writing - original draft: Yoon YK.

- Writing - review & editing: Lee J, Kim SI, Peck KR.

References

- 1.Armocida B, Formenti B, Ussai S, Palestra F, Missoni E. The Italian health system and the COVID-19 challenge. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e253. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30074-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemos DR, D'Angelo SM, Farias LA, Almeida MM, Gomes RG, Pinto GP, et al. Health system collapse 45 days after the detection of COVID-19 in Ceará, Northeast Brazil: a preliminary analysis. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2020;53:e20200354. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0354-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang WH, Guan WJ, Li CC, Li YM, Liang HR, Zhao Y, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalised patients with COVID-19 treated in Hubei (epicentre) and outside Hubei (non-epicentre): a nationwide analysis of China. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(6):2000562. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00562-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coddington DC, Moore KD, Fischer EA. Integrated Health Care: Reorganizing the Physician, Hospital and Health Plan Relationship. Englewood, CO: Center for Research in Ambulatory Health Care Administration (US); 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dev N, Kumar V, Sankar J. COVID-19 infection outbreak among health care workers: perspective from a low-middle income country. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2020;90(3) doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2020.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung HS, Lee DE, Kim JK, Yeo IH, Kim C, Park J, et al. Revised triage and surveillance protocols for temporary emergency department closures in tertiary hospitals as a response to COVID-19 crisis in Daegu Metropolitan City. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(19):e189. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saunders-Hastings PR, Krewski D. Reviewing the history of pandemic influenza: understanding patterns of emergence and transmission. Pathogens. 2016;5(4):66. doi: 10.3390/pathogens5040066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morens DM, Taubenberger JK, Harvey HA, Memoli MJ. The 1918 influenza pandemic: lessons for 2009 and the future. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(4) Suppl:e10–e20. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181ceb25b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(Suppl 1):6–20. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones K. Mission drift in qualitative research, or moving toward a systematic review of qualitative studies, moving back to a more systematic narrative review. Qual Rep. 2004;9(1):94–111. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Nguyen H, Van Hoang M, Dao AT, Nguyen HL, Van Nguyen T, Nguyen PT, et al. An adaptive model of health system organization and responses helped Vietnam to successfully halt the COVID-19 pandemic: What lessons can be learned from a resource-constrained country. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2020;35(5):988–992. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee CC, Thampi S, Lewin B, Lim TJ, Rippin B, Wong WH, et al. Battling COVID-19: critical care and peri-operative healthcare resource management strategies in a tertiary academic medical centre in Singapore. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(7):861–871. doi: 10.1111/anae.15074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Archbald-Pannone LR, Harris DA, Albero K, Steele RL, Pannone AF, Mutter JB. COVID-19 collaborative model for an academic hospital and long-term care facilities. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(7):939–942. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unroe KT, Vest J. Time to leverage health system collaborations: Supporting nursing facilities through the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(6):1129–1130. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim T. Improving preparedness for and response to coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) in long-term care hospitals in Korea. Infect Chemother. 2020;52(2):133–141. doi: 10.3947/ic.2020.52.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang D, Pan S, Li Z, Yuan T, Jiang B, Gan D, et al. Large-scale public venues as medical emergency sites in disasters: lessons from COVID-19 and the use of Fangcang shelter hospitals in Wuhan, China. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(6):e002815. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noh JY, Song JY, Yoon JG, Seong H, Cheong HJ, Kim WJ. Safe hospital preparedness in the era of COVID-19: the Swiss cheese model. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;98:294–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daumas RP, Silva GA, Tasca R, Leite ID, Brasil P, Greco DB, et al. The role of primary care in the Brazilian healthcare system: limits and possibilities for fighting COVID-19. Cad Saude Publica. 2020;36(6):e00104120. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00104120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim H, Kim D, Paul C, Lee CK. The spatial allocation of hospitals with negative pressure isolation rooms in Korea: Are we prepared for new outbreaks? Int J Health Policy Manag. 2020 doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.118. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim T, Choi MJ, Kim SB, Kim JY, Lee J, Oh HS, et al. Strategical preparedness and response actions in the healthcare system against coronavirus disease 2019 according to transmission scenario in Korea. Infect Chemother. 2020;52(3):389–395. doi: 10.3947/ic.2020.52.3.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cancedda C, Davis SM, Dierberg KL, Lascher J, Kelly JD, Barrie MB, et al. Strengthening health systems while responding to a health crisis: Lessons learned by a nongovernmental organization during the Ebola virus disease epidemic in Sierra Leone. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(suppl 3):S153–S163. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi S. A hidden key to COVID-19 management in Korea: public health doctors. J Prev Med Public Health. 2020;53(3):175–177. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.20.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y, Wang H, Chen J, Zhang X, Yue X, Ke J, et al. Emergency management of nursing human resources and supplies to respond to coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic. Int J Nurs Sci. 2020;7(2):135–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keeley C, Jimenez J, Jackson H, Boudourakis L, Salway RJ, Cineas N, et al. Staffing up for the surge: expanding the New York City public hospital workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff (Millwood) 2020;39(8):1426–1430. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huh K, Shin HS, Peck KR. Emergent strategies for the next phase of COVID-19. Infect Chemother. 2020;52(1):105–109. doi: 10.3947/ic.2020.52.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bemah P, Baller A, Cooper C, Massaquoi M, Skrip L, Rude JM, et al. Strengthening healthcare workforce capacity during and post Ebola outbreaks in Liberia: an innovative and effective approach to epidemic preparedness and response. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;33(Suppl 2):9. doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2019.33.2.17619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramachandran P, Swamy L, Kaul V, Agrawal A. A national strategy for ventilator and ICU resource allocation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Chest. 2020;158(3):887–889. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romney D, Fox H, Carlson S, Bachmann D, O'Mathuna D, Kman N. Allocation of scarce resources in a pandemic: a systematic review of US state crisis standards of care documents. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, Thome B, Parker M, Glickman A, et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2049–2055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ranney ML, Griffeth V, Jha AK. Critical supply shortages - The need for ventilators and personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):e41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2006141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koonin LM, Pillai S, Kahn EB, Moulia D, Patel A. Strategies to inform allocation of stockpiled ventilators to healthcare facilities during a pandemic. Health Secur. 2020;18(2):69–74. doi: 10.1089/hs.2020.0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dargaville T, Spann K, Celina M. Opinion to address the personal protective equipment shortage in the global community during the COVID-19 outbreak. Polym Degrad Stabil. 2020;176:109162. doi: 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2020.109162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gopichandran V, Subramaniam S. Response to COVID-19: an ethical imperative to build a resilient health system in India. Indian J Med Ethics. 2020;V(2):1–4. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2020.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desjardins MR, Hohl A, Delmelle EM. Rapid surveillance of COVID-19 in the United States using a prospective space-time scan statistic: detecting and evaluating emerging clusters. Appl Geogr. 2020;118:102202. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2020.102202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balajee SA, Arthur R, Mounts AW. Global health security: building capacities for early event detection, epidemiologic workforce, and laboratory response. Health Secur. 2016;14(6):424–432. doi: 10.1089/hs.2015.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitelaw S, Mamas MA, Topol E, Van Spall HG. Applications of digital technology in COVID-19 pandemic planning and response. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2(8):e435–40. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30142-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim K, Andrew SA, Jung K. Public health network structure and collaboration effectiveness during the 2015 MERS outbreak in South Korea: an institutional collective action framework. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(9):1064. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14091064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lai AY. Organizational collaborative capacity in fighting pandemic crises: a literature review from the public management perspective. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2012;24(1):7–20. doi: 10.1177/1010539511429592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.AlKhaldi M, Kaloti R, Shella D, Al Basuoni A, Meghari H. Health system's response to the COVID-19 pandemic in conflict settings: policy reflections from Palestine. Glob Public Health. 2020;15(8):1244–1256. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2020.1781914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ning Y, Ren R, Nkengurutse G. China's model to combat the COVID-19 epidemic: a public health emergency governance approach. Glob Health Res Policy. 2020;5:34. doi: 10.1186/s41256-020-00161-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palagyi A, Marais BJ, Abimbola S, Topp SM, McBryde ES, Negin J. Health system preparedness for emerging infectious diseases: a synthesis of the literature. Glob Public Health. 2019;14(12):1847–1868. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2019.1614645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carney T, Bennett B. Framing pandemic management: new governance, science or culture? Health Sociol Rev. 2014;23(2):136–147. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee HY, Oh MN, Park YS, Chu C, Son TJ. Public health crisis preparedness and response in Korea. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2013;4(5):278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.phrp.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peck KR. Early diagnosis and rapid isolation: response to COVID-19 outbreak in Korea. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(7):805–807. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Appleby J. What is happening to non-COVID deaths? BMJ. 2020;369:m1607. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Government of Singapore. Looking for PHPC near you? [Updated 2020]. [Accessed October 13, 2020]. https://www.flugowhere.gov.sg/

- 47.Kwon KT, Ko JH, Shin H, Sung M, Kim JY. Drive-through screening center for COVID-19: a safe and efficient screening system against massive community outbreak. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(11):e123. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim SI, Lee JY. Walk-through screening center for COVID-19: an accessible and efficient screening system in a pandemic situation. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(15):e154. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park PG, Kim CH, Heo Y, Kim TS, Park CW, Kim CH. Out-of-hospital cohort treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 patients with mild symptoms in Korea: an experience from a single community treatment center. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(13):e140. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sheehy LM. Considerations for postacute rehabilitation for survivors of COVID-19. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e19462. doi: 10.2196/19462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.National Centre for Infectious Diseases (SG) For patients and visitors. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed October 13, 2020]. https://www.ncid.sg/Patients-and-Visitors/Visit-a-Specialist/Overview/Pages/default.aspx.

- 52.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang J, Zhou M, Liu F. Reasons for healthcare workers becoming infected with novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105(1):100–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu M, Cheng SZ, Xu KW, Yang Y, Zhu QT, Zhang H, et al. Use of personal protective equipment against coronavirus disease 2019 by healthcare professionals in Wuhan, China: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2020;369:m2195. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.World Health Organization. WHO surge calculators. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed October 13, 2020]. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/covid-19-critical-items.

- 56.World Health Organization. List of priority medical devices for COVID-19 case management. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed October 13, 2020]. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/list-of-priority-medical-devices-for-covid-19-case-management.

- 57.Davis JR, Lederberg J. Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Emerging Infections. Public Health Systems and Emerging Infections: Assessing the Capabilities of the Public and Private Sectors: Workshop Summary. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press (US); 2000. 3. Surveillance. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thacker SB, Berkelman RL. Public health surveillance in the United States. Epidemiol Rev. 1988;10:164–190. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nsubuga P, White ME, Thacker SB, Anderson MA, Blount SB, Broome CV, et al. Chapter 53. Public health surveillance: a tool for targeting and monitoring interventions. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, et al., editors. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd edition. Washington, D.C.: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 60.World Health Organization. Public health surveillance for COVID-19: interim guidance. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed October 13, 2020]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-2019-nCoV-surveillanceguidance-2020.7.

- 61.Setel P, AbouZahr C, Atuheire EB, Bratschi M, Cercone E, Chinganya O, et al. Mortality surveillance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Bull World Health Organ. 2020;98(6):374. doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.263194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.World Health Organization. Sentinel surveillance. [Accessed October 13, 2020]. https://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/burden/vpd/surveillance_type/sentinel/en/

- 63.Korean Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Laboratory surveillance for infectious diseases. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed October 13, 2020]. http://www.cdc.go.kr/contents.es?mid=a20301090503.

- 64.Choi WS. The national influenza surveillance system of Korea. Infect Chemother. 2019;51(2):98–106. doi: 10.3947/ic.2019.51.2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. COVID-19: the CIDRAP viewpoint. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed October 13, 2020]. https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/sites/default/files/public/downloads/cidrap-covid19-viewpoint-part5.pdf.

- 66.Dighe A, Cattarino L, Cuomo-Dannenburg G, Skarp J, Imai N, Bhatia S, et al. Response to COVID-19 in South Korea and implications for lifting stringent interventions. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):321. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01791-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ali I. COVID-19: Are we ready for the second wave? Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]