Abstract

Vulvar malignant melanoma (VMM), although uncommon, comprises 5-10% of all vulvar malignancies. Local control is notoriously poor in VMM with recurrence rates of 30-50% compared to approximately 3% in cutaneous melanomas. We studied clinicopathologic features of 37 women with VMM, after reviewing three decades of clinical follow up data in our institutional databases. Most patients were Caucasian (n=35) with an average age at diagnosis of 60.6 years (range 23-83). The most common subtype was mucosal lentiginous melanoma (n=25). We compared Kaplan-Meier survival curves of 31 patients defined by clinical and microscopic attributes using exact log-rank tests. Younger patients at diagnosis (23-64 yo), those with thin melanomas (≤1mm) and those with Clark's level II or III tumors had better 5 year survival rates than older patients (65-83 yo), and those with thick melanomas (>1mm) and those with Clark's level IV or V (p<=0.05), respectively, by exact log-rank test. Local recurrence of melanoma occurred in fifteen patients. Nine patients (24%) had eventual urethral involvement by malignant melanoma, and this feature was associated with significantly shorter survival (p=0.036). Patients with urethral involvement had shorter median time to death and worse 5-year survival rates. Given that spread to the urethra is common in VMM and urethral recurrence is also associated with mortality, pathology excision specimens should be carefully reviewed with attention to urethral involvement as a potentially important prognostic factor.

Keywords: Vulvar malignant melanoma, Mucosal melanoma, Urethral involvement, Survival analysis, Local recurrence

Introduction

Mucosal melanoma is a rare subtype of melanoma which comprises about 4% of all melanoma cases [1,2]. The most common mucosal sites are head and neck (55%), anorectal (24%), vulvovaginal (18%) and genitourinary areas (3%) [1,2] Mucosal melanoma differs significantly from cutaneous melanoma with regard to risk factors, tumor biology, clinical manifestations, and management [1] Sun exposure is a very well known etiological factor for cutaneous malignant melanoma, unlike mucosal melanomas, that arise on sun-protected parts of the body [3]. Vulvar malignant melanoma (VMM) is a subtype of mucosal melanomas arising on the female genital tract. VMM accounts for 1% to 3% of all melanomas diagnosed in women, represents 5-10% of all vulvar malignancies and is the second most common histological type of vulvar cancer [4]. The most frequent symptoms associated with VMM are bleeding, pruritus, difficulty in micturition and a palpable mass [1,2]. Diagnosis of VMM is typically delayed due to a lack of early or specific signs and symptoms, as well as the location of lesions in areas that are difficult to visualize on physical examination. VMM is characterized by low survival and high recurrence rates; many patients present with metastasis – features that often lead to poor outcomes and high mortality [1,5].

Both primary and metastatic melanoma involving the urinary tract are rare and scattered cases are reported in literature about primary or metastatic urethral melanoma [6,7]. Multiple studies have reported increased involvement of midline structure (urethra, clitoris, introitus) in VMM [8,9,10] but few of the previously reported studies independently considered urethral involvement in VMM as an important prognostic factor or have studied in depth [11]. VMM has been considered as a distinct entity among mucosal melanomas [8,9,10,12] Various prognostic factors (e.g., patient age, Breslow depth, dermal mitotic rate and lymph node involvement) have been accepted while some other factors are still controversial [8,12,13].

Management and follow up criteria for VMM which have been used are the same as for cutaneous melanoma. While surgery is usually considered the primary treatment, there are no clear guidelines for sentinel lymph node dissection in VMM [12]. The impact of urethral involvement in VMM is uncertain. Therefore, this study evaluated the outcomes in 37 patients with VMM with and without urethral involvement. In addition to that we also present clinicopathological characteristics of VMM and evaluate five-year overall survival and recurrence rate in subgroups defined by these factors.

Methods

Study Patients and Study Design

Our study cohort included 37 women with VMM seen at the Pigmented Lesion Clinic at the Hospital of University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA between 1970-2000 after careful reviewing the clinical database. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pennsylvania.

Pathological Variables.

“Urethral involvement” in our study was defined as involvement of urethral structures in subsequent followup as an extension of tumor and or metastasis by primary VMM. Histologic slides and pathological reports of each VMM specimen were reviewed by two different dermatopathologists and a trainee. Histologically each melanoma was evaluated for histologic subtype, radial growth phase (RGP), vertical growth phase (VGP), predominant cell types in each phase, Breslow thickness, Clark level, and dermal mitotic index. The presence of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), neurotropism, lymphovascular invasion, ulceration, and resection margins were also reported. Clinical and gross lesion descriptions and microscopic findings were used to assess the extent of disease and possible multifocality.

Clinical Variables.

Clinical data available included age at the time of diagnosis, race, clinical stage, lesion location, clinical description of the lesion, and presentation were ascertained from clinical notes and the electronic medical record database. Demographic and clinical information was recorded, and all histologic diagnoses were confirmed. Clinical follow up data (i.e., alive with no evidence of disease, alive with disease, died of disease) of the patients was collected from institutional medical records and various public database resources. Time to death and time to regional lymph node (RLN) recurrence was calculated as the time between diagnosis and the event. Patients lost to follow-up were censored at the date of the last follow-up. Clinocopathological variables in regards to missing follow-up data have been specifically mentioned in the results and discussion section. The median follow-up time was 33 months.

Statistical Methods.

The data were summarized using descriptive statistics. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were calculated for patients in subgroups defined using clinical (e.g., age at diagnosis, race ) and microscopic attributes (e.g., Clark level, tumor thickness, lymphovascular invasion, clinical multifocality, urethral involvement, microscopic amelanotic areas, RGP and VGP). The exact log-rank test was used to evaluate differences in survival and recurrence curves among groups. Five-year overall survival rates were computed from the estimated survival curves. A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

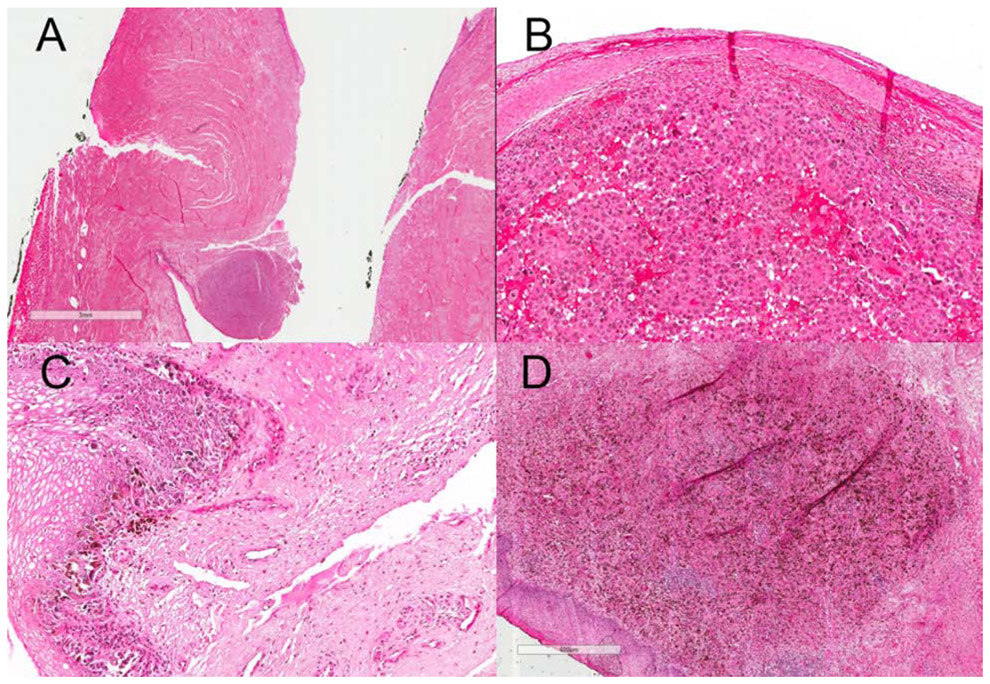

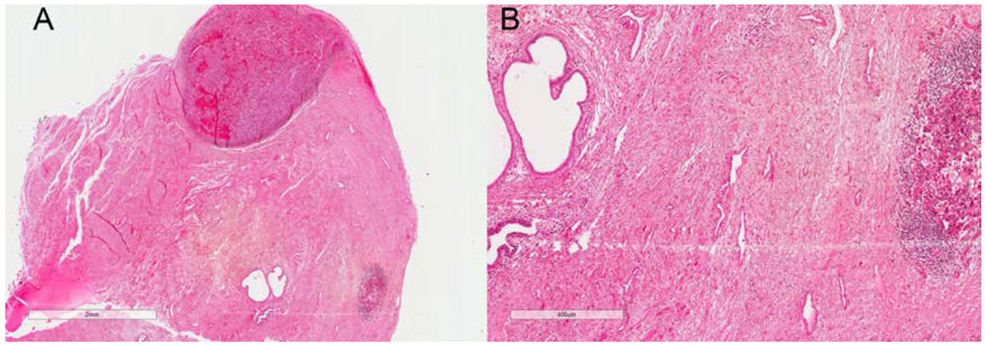

The clinicopathologic characteristics of the 37 study patients are summarized in Table 1. The median age at diagnosis was 66 years (range, 23 to 39 years). Thirty-five (35/37, 95%) patients were Caucasian and the remaining two patients were African American. The most common histologic subtype was mucosal lentiginous melanoma (25/37, 68%). Other cases were classified as superficial spreading melanoma (5/37, 14%), nodular melanoma (3/37, 8%), with remaining (4/37, 10%) considered to be unclassified. Histologically, the invasive component of VMM, like that of any other cutaneous malignant melanoma, is characterized by atypical epitheliod or occasionally spindle melanocytes in the dermis with mitotic activity and variable abundance of melanin pigment. (Figure 1, 2)

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| All Patients (n=37) |

Patients with follow up (n=31) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Percent | N | Percent | ||

| Tumor Thickness | |||||

| 0 | 6 | 16.2 | 5 | 16.1 | |

| 0.01-1.00 mm | 7 | 18.9 | 5 | 16.1 | |

| > 1.00mm | 23 | 62.2 | 20 | 64.5 | |

| Unknown | 1 | 2.7 | 1 | 3.2 | |

| Clark’s Level | |||||

| II or III | 11 | 29.7 | 8 | 25.8 | |

| IV or V | 16 | 43.2 | 14 | 41.2 | |

| Unknown | 10 | 27.0 | 9 | 29.0 | |

| Ulceration | |||||

| Present | 15 | 40.5 | 13 | 41.9 | |

| Absent | 7 | 18.9 | 6 | 19.4 | |

| Unknown | 15 | 40.5 | 12 | 38.7 | |

| Lymphovascular Invasion | |||||

| Present | 8 | 21.6 | 7 | 22.6 | |

| Absent | 13 | 35.1 | 10 | 32.3 | |

| Unknown | 16 | 43.2 | 14 | 45.2 | |

| VGP Mitotic Rate | |||||

| 0 | 1 | 2.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 1-6 | 6 | 16.2 | 6 | 19.4 | |

| >6 | 10 | 27.0 | 8 | 25.8 | |

| Unknown | 20 | 54.1 | 17 | 54.8 | |

| Histologic Amelanotic foci | |||||

| 1 | Yes | 19 | 51.4 | 16 | 51.6 |

| 0 | No | 18 | 48.7 | 15 | 48.4 |

| Clinical Multifocality | |||||

| 1 | Present | 13 | 35.1 | 13 | 41.9 |

| 0 | Absent | 24 | 64.9 | 18 | 58.1 |

| Urethral Involvement | |||||

| 1 | Yes | 9 | 24.3 | 9 | 29.0 |

| 0 | No | 28 | 75.7 | 22 | 71.0 |

| Age at Diagnosis | |||||

| 23-64 yrs | 17 | 46.0 | 15 | 48.4 | |

| 65-83 yrs | 20 | 54.1 | 16 | 51.6 | |

Figure 1:

A : Scanning magnification view (3X view) of VMM showing atypical epitheliod cells (melanocytes) in epidermis on H&E slide; Higher magnification (300X view, B & C and 600X view, D) of VMM showing atypical epitheliod cells (melanocytes) in epidermis and dermis with scattered melanin pigments in dermis on H&E slide

Note: The glass slide is almost 34 years old, and there has been some fading over time.

Figure 2:

A: Scanning magnification view (2X view) of VMM showing periurethral involvement by VMM and dermal boundaries in relation to Clark level of invasion and tumor thickness on H&E slide; B: Higher magnification view (400X view) of periurethral involvement by VMM and atypical epitheliod cells (melanocytes) in dermis on H&E slide

Note: The glass slide is almost 34 years old, and there has been some fading over time.

Urethral involvement by melanoma was identified in nine patients (9/37, 24%). Fifteen patients (15/22, 68%) had histologic evidence of ulceration, twenty-three patients (23/36, 63%) had tumor thickness greater than 1 mm and in sixteen patients (16/27, 59%), tumor had Clark level III/IV invasion.Microscopically amelanotic foci were found in nineteen patients (19/37, 51%).

Clinical follow up was available for 31 patients (31/37, 84%) and their median follow-up time was 33 months (Table 2). Fifteen patients developed a local recurrence (15/37, 40%) and twelve patients developed distant metastasis (12/37, 32%) during follow up. Follow up on regional lymph node recurrence was available for 24 patients (24/37, 64%). For the 13 patients (13/24, 54%) who developed regional lymph node recurrence, the median time to this recurrence was 25 months. For the cohort of twenty patients (20/31, 64%) who died of disease, the median time to death was 27 months. At the last follow up, six patients were alive without evidence of disease, five patients were alive with metastatic disease and twenty patients had died of disease.

Table 2.

Five-Year Survival Rates, Median Follow up and Median Time to Death (n=31)

| N | Exact Log- rank test p-value |

Five-Year Survival Rates (Percent) |

Median Follow up* (Months) |

Deaths N |

Median Time to Death (Months) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Thickness** |

0.003 | ||||||

| 0 | 5 | 100.0 | 81.0 | 0 | |||

| 0.01-1.0mm | 7 | 50.0 | 29.0 | 4 | 78.5 | ||

| > 1.00mm | 23 | 27.2 | 24.5 | 15 | 25.0 | ||

| Clark’s Level | 0.041 | ||||||

| II or III | 8 | 66.7 | 49.5 | 4 | 78.5 | ||

| IV or V | 14 | 20.0 | 24.5 | 11 | 25.0 | ||

| Unknown | 9 | 55.6 | 60.0 | 5 | 25.0 | ||

| Urethral Involvement |

0.036 | ||||||

| 1 | Yes | 9 | 12.5 | 24.0 | 8 | 24.5 | |

| 0 | No | 22 | 57.0 | 46.0 | 12 | 40.0 | |

| Age at Diagnosis | 0.034 | ||||||

| 23-64 years | 15 | 58.7 | 60 | 9 | 44.0 | ||

| 65-83 years | 16 | 25.6 | 15.5 | 11 | 23.0 | ||

| Clinical Multifocality |

0.071 | ||||||

| 1 | Yes | 13 | 20.0 | 23 | 9 | 24.0 | |

| 0 | No | 24 | 58.2 | 52 | 11 | 36.0 | |

Time from diagnosis to last follow up.

One patient with unknown thickness excluded from the analysis.

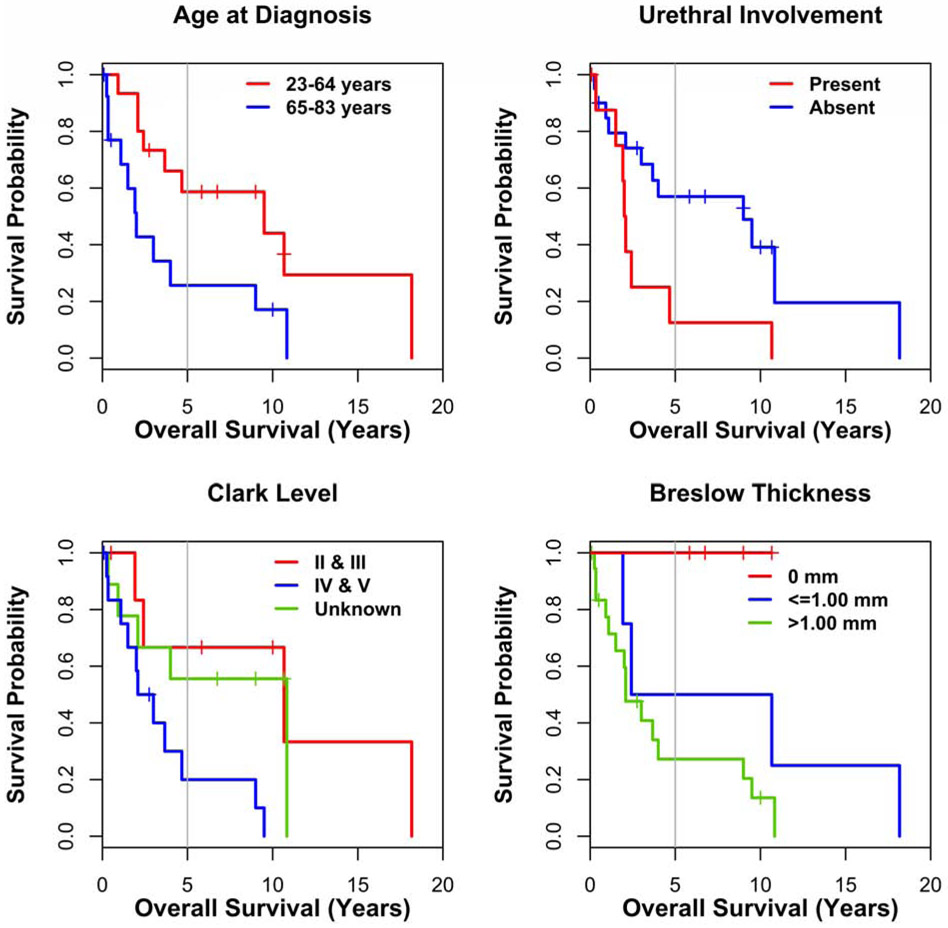

Survival curves differed significantly for patients who had urethral involvement (vs uninvolved, p=0.036, 5-year survival rates 13% vs 57%, respectively), were of older age at the time of diagnosis (>=65 vs <=64, p=0.034, 5-year survival rates 26% vs 59%, respectively), had Clark level of tumor invasion IV/V (vs II/III, p=0.041, 5-year survival rates 20% vs 67%, respectively,) and had tumor thickness >1mm (vs <=1mm, p=0.003, 5-year survival rates 27% vs 50%), respectively (Figure 3). The log-rank test evaluating the difference between the curves for time to regional lymph node recurrence for patients with and without histological amelanotic foci was not significant (p=0.069).

Figure 3:

Prognostic factors for VMM patients (n=31). Kaplan-Meier curves for factors predictive of overall survival: age at diagnosis, urethral involvement, Clark level and Breslow thickness.

Discussion

For our patients with VMM, urethral involvement identified on histopathology was a significant, poor prognostic factor. The 5-year overall survival rates for VMM patients with and without involvement of urethra by malignant melanoma were 13 vs 57%, respectively. Among nine women had eventual involvement of the urethra by malignant melanoma, there were eight patients with information about local recurrence; out of which five patients developed local recurrence(5/8, 62%). These local recurrence rates are higher than overall local recurrence (40%) reported in our study. Younger patients at diagnosis (23-64 years old), and those with thin melanoma (<=1mm) and Clark level II or III had better 5 year survival rates than older patients (65-83 years old), and those with thick melanoma (>1mm) and Clark level IV or V by Kaplan Meier survival curves (p<=0.05). About 40% of mucosal melanomas are amelanotic, unlike 10% of cutaneous melanomas [1]. In our study cohort of VMM, 51% of patients also had histologic evidence of amelanotic foci. In a study of 100 patients with VMM, Nagarajan et al. showed tumor thickness and dermal mitotic rate were key variables associated with prognosis of VMM [8]. Traditionally, variables such as age, Clark level, tumor thickness [8,9,13], lymph node involvement [9], mitotic rate [8] have been studied for survival analysis [8], however presence/absence of urethral involvement as a prognostic factor has not been well studied in VMM.

Prior studies have described involvement of midline structures by VMM [8,9,10]. Raspagliesi et al.[9] and Iacoponi et al.[10], had 30% (12/30) involvement of midline structures (clitoris, urethra) and 45% (19/42) involvement of midline, respectively, in their studies of VMM. However, those prior studies did not focus specifically on urethral involvement in VMM as an important prognostic factor [8,9,10,11]. There have been few reports of urethral recurrence and urethral involvement in patients with vulvar melanoma in the literature [1,3]. This was observed in 24% or our patients. Such involvement can result in management difficulties, relating to the extent of surgery that may be indicated for cases at primary presentation, and in follow-up [1,3]. Our study showed that the median time to death for patients with the presence of urethral involvement in VMM was much shorter compared to those without urethral involvement. Therefore, urethral involvement should be identified and managed carefully. Lungs, vagina, liver and brain are commonly reported metastatic sites in vulvar melanoma in the literature [3,14,15].

Urethral involvement has been reported in cases of VMM, but it has not been studied as an independent prognostic factor to this date [1,3]. Patients with VMM generally have a poor prognosis, with reported 5-year survival rates ranging between 10% and 63% concordant with our stduy [12,16,17] Low survival rates are attributed to the late stage often found at diagnosis and high recurrence rates [12,16,18]. Other studies suggested that a substantial number of recurrences occur late (>5 years) [12,10] and, ten-year survival rates may be more informative than five-year survival rates possibly due to late recurrences [12,10] Local recurrence occurs in approximately 30-50 % of women with vulvar melanoma, while only about 3-5% of cutaneous melanomas recur locally [12,10,19]. Studies have reported high locoregional recurrence rates (53%), distant recurrence rates (28%) and both locoregional and distant recurrence (19%) in VMM [12,19] . High local (40%) and locoregional LN recurrence (54%) has been observed in our cohort, as well. This issue of high local recurrence should be addressed in management and follow- up planning.

The primary aim of clinical follow-up of any type of cancer, including melanoma, is to detect locoregional or distant recurrences in an early stage to improve the long-term survival [12,20]. There are no guidelines on VMM follow up, and schedules are usually based on clinical experience and customary practice rather than on evidence. However, evaluation of these current follow-up regimes has not been undertaken to this date [12]. As for any high-risk vulvar malignancy the most often used follow-up scheme consists of appointments starting 6–8 weeks postoperative, then every 3–4 months in the first two years post-diagnosis and then twice a year in the 3rd and 4th year [12]. However, due to higher recurrence rates and common late recurrences(> 5 years), a long-term follow-up plan may need to be considered is needed [12,21].

Melanoma of mucosal sites (VMM, rectal and sinonasal) have historically demonstrated interesting pathological challenges [8]. The histology of vulvar skin represents some unique complexities, having keratinized and nonkeratinized epithelium depending on vulvar region. Labia majora skin is composed of keratinized squamous epithelium with all skin adnexa, which transitions to non keratinized squamous mucosa in the labia minora [8,22]. The measurement of tumor depth by Breslow thickness is still the best criterion for staging, which was also evident in our cohort as well [12,22].

Our study reported higher rate of regional lymph node recurrences (54%). Although we did not study Lymph node (LN) status as a prognostic factor, positive LN status has been shown to be of prognostic significance for distant recurrence in VMM [12,9]. Multiple studies have shown that the evaluation of LN status is a possible prognostic factor in VMM. Ten-year survival rates are 11.5% in the LN positive cases and 43.8% in the LN negative cases [12,23,24,25]. The five-year survival rate in LN positive patients averaged 23.4% (range 0–68%) [12,9,23,24,25]. Additionally, the extent of LN involvement is shown to be prognostic for survival [12,9]. After a thorough review of the literature, it appears that average survival rates for VMM with 0, 1 or more than 2 positive lymph nodes are respectively 65%, 20% and 0% [2,12].

Our cohort had a high rate of metastasis and death (64%). Since the time of our study, Two studies, by Hou et al. and Dias-Santagata et al.. showed that approximately 20% and 44% of VMM, respectively, are found to have KIT mutations [13,26] and these can potentially be responsive to targeted therapy in metastatatic or inoperable local disease. Of important note, Dias-Santagata et al. highlighted CD117 overexpression and KIT mutations, as factors indicating better survival in VMM without further disease progression [13]. Furthermore, Heinzelmann-Schwarz et al. showed 26% of VMM cases had a BRAF mutation, 50% of them in codons other than the canionical V600E [16] and Dias-Santagata et al. showed BRAF mutation in 25% of VMM cases [13]. Results of immune therapy with checkpoint inhibitors may be disappointing, likely because these melanomas tend to have a low tumor mutation burden implying limited antigenicity, however a response rate of approximately 28% has been recently documented in a small study of vulvar, vaginal and cervical mucosal melanomas and these novel systemic therapies have proven to improve survival in vulvar melanoma [27].

Conclusion

Vulvar melanoma is an insidious disease often with microscopic amelanotic foci, clinical multifocality and ill-defined borders. Spread to the urethra is common and a frequent source of recurrence and urethral recurrence is associated with mortality. Hence, pathology excision specimens should be carefully reviewed with particular attention to urethral involvement. High local recurrence of vulvar melanoma is associated with mortality and factors contributing to local recurrence should be carefully reviewed.

Vulvar malignant melanoma is a subtype of mucosal melanomas arising on the female genital tract.

High local recurrence of vulvar melanoma is associated with mortality and factors contributing to local recurrence should be carefully reviewed.

Spread to the urethra is common and a frequent source of recurrence and urethral recurrence is associated with mortality in vulvar melanoma.

Acknowledgement:

All authors would like to thank Dr. Wallace H. Clark. Jr for his contribution towards the case study population.

Funding support: The research was supported by the National Institute of Health (P50CA174523).

Footnotes

Disclosure : No disclosures

Conflict of interest : No conflict of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brasero Burgos J, Gómez de Vicente JM, F de A Donis Canet, et al. Recurrent vulvar melanoma invading urethra. Clinical case and literature review. Urol Case Rep. 2018;19:42–44. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Truong H, Sundi D, Sopko N, Xing D, Lipson EJ, Bivalacqua TJ. A Case Report of Primary Recurrent Malignant Melanoma of the Urinary Bladder. Urol Case Rep. 2013;1(1):2–4. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2013.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lemańska A, Banach P, Magnowska M, Frankowski A, Nowak-Markwitz E, Spaczyński M. Vulvar melanoma with urethral invasion and bladder metastases – a case report and review of the literature. Arch Med Sci. 2015;11(1):240–252. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2013.36184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinasac SE, Petrella TM, Rouzbahman M, Sade S, Ghazarian D, Vicus D. Melanoma of the Vulva and Vagina: Surgical Management and Outcomes Based on a Clinicopathologic Reviewof 68 Cases. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019;41(6):762–771. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2018.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang AE, Karnell LH, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on cutaneous and noncutaneous melanoma: a summary of 84,836 cases from the past decade. The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Cancer. 1998;83(8):1664–1678. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takamatsu D, Shiota M, Sugimoto M, et al. A case report of primary malignant melanoma of male urethra with distinct appearance in multiple regions. Int Cancer Conf J. 2016;5(4):174–177. doi: 10.1007/s13691-016-0252-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szabó B, Szűcs M, Horváth A, et al. [Mucosal melanoma primary and metastatic cases with urogenital localization in our department]. Orv Hetil. 2019;160(10):378–385. doi: 10.1556/650.2019.31303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagarajan P, Curry JL, Ning J, et al. Tumor Thickness and Mitotic Rate Robustly Predict Melanoma-Specific Survival in Patients with Primary Vulvar Melanoma: A Retrospective Review of 100 Cases. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(8):2093–2104. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raspagliesi F, Ditto A, Paladini D, et al. Prognostic indicators in melanoma of the vulva. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7(10):738–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iacoponi S, Rubio P, Garcia E, et al. Prognostic Factors of Recurrence and Survival in Vulvar Melanoma: Subgroup Analysis of the VULvar CANcer Study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26(7):1307–1312. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chokoeva A, Tchernev G, Wollina U. [Vulvar melanoma]. Akush Ginekol (Sofiia). 2015;54(2):56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boer FL, Ten Eikelder MLG, Kapiteijn EH, Creutzberg CL, Galaal K, van Poelgeest MIE. Vulvar malignant melanoma: Pathogenesis, clinical behaviour and management: Review of the literature. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019;73:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dias-Santagata D, Selim MA, Su Y, et al. KIT mutations and CD117 overexpression are markers of better progression-free survival in vulvar melanomas. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(5):1376–1384. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baiocchi G, Duprat JP, Neves RI, et al. Vulvar melanoma: report on eleven cases and review of the literature. Sao Paulo Med J. 2010;128(1):38–41. doi: 10.1590/s1516-31802010000100008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jahnke A, Makovitzky J, Briese V. Primary melanoma of the female genital system: a report of 10 cases and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2005;25(3A):1567–1574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinzelmann-Schwarz VA, Nixdorf S, Valadan M, et al. A clinicopathological review of 33 patients with vulvar melanoma identifies c-KIT as a prognostic marker. Int J Mol Med. 2014;33(4):784–794. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheistrøen M, Tropé C, Koern J, Pettersen EO, Abeler VM, Kristensen GB. Malignant melanoma of the vulva. Evaluation of prognostic factors with emphasis on DNA ploidy in 75 patients. Cancer. 1995;75(1):72–80. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ditto A, Bogani G, Martinelli F, et al. Surgical Management and Prognostic Factors of Vulvovaginal Melanoma. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20(3):e24–29. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verschraegen CF, Benjapibal M, Supakarapongkul W, et al. Vulvar melanoma at the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center: 25 years later. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2001;11(5):359–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trotter SC, Sroa N, Winkelmann RR, Olencki T, Bechtel M. A Global Review of Melanoma Follow-up Guidelines. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6(9):18–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehra T, Grözinger G, Mann S, et al. Primary localization and tumor thickness as prognostic factors of survival in patients with mucosal melanoma. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11):e112535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kesic V Colposcopy of the vulva, perineum and anal canal. :39. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trimble EL, Lewis JL, Williams LL, et al. Management of vulvar melanoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1992;45(3):254–258. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(92)90300-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Räber G, Mempel V, Jackisch C, et al. Malignant melanoma of the vulva: Report of 89 patients. Cancer. 1996;78(11):2353–2358. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeMatos P, Tyler D, Seigler HF. Mucosal melanoma of the female genitalia: a clinicopathologic study of forty-three cases at Duke University Medical Center. Surgery. 1998;124(1):38–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hou JY, Baptiste C, Hombalegowda RB, et al. Vulvar and vaginal melanoma: A unique subclass of mucosal melanoma based on a comprehensive molecular analysis of 51 cases compared with 2253 cases of nongynecologic melanoma. Cancer. 2017;123(8):1333–1344. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Indini A, Di Guardo L, Cimminiello C, Lorusso D, Raspagliesi F, Del Vecchio M. Investigating the role of immunotherapy in advanced/recurrent female genital tract melanoma: a preliminary experience. J Gynecol Oncol. 2019;30(6):e94. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2019.30.e94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]