Abstract

Objectives:

To determine if plasma microbial small RNAs (sRNAs) are altered in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) compared to control subjects, associated with RA disease-related features, and altered by disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

Methods:

Small RNA sequencing was performed on plasma from 165 RA patients and 90 matched controls and a separate cohort of 70 RA patients before and after starting a DMARD. Genome alignments for RA-associated bacteria, representative bacterial and fungal human microbiome genomes and environmental bacteria were performed. Microbial genome counts and individual sRNAs were compared across groups and correlated with disease features. False discovery rate was set at 0.05.

Results:

Genome counts of Lactobacillus salivarius, Anaerobaculum hydrogeniformans, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, Paenisporosarcina sp., Facklamia hominis, Sphingobacterium spiritivorum, Lentibacillus amyloliquefaciens, Geobacillus sp., and Pseudomonas fluorescens were significantly decreased in the plasma of RA compared to control subjects. Three microbial transfer RNA-derived sRNAs were increased in RA versus controls and inversely associated with disease activity. Higher total microbial sRNA reads were associated with lower disease activity in RA. Baseline total microbial sRNAs were 3-fold higher among patients who improved with DMARD versus those who did not but did not change significantly after 6 months of treatment.

Conclusion:

Plasma microbial sRNA composition is altered in RA versus control subjects and associated with some measures of RA disease activity. DMARD treatment does not alter microbial sRNA abundance or composition, but increased abundance of microbial sRNAs at baseline was associated with disease activity improvement at six months.

Small RNAs (sRNAs) are short single-stranded non-coding RNAs that regulate biological processes and serve as disease biomarkers. MicroRNAs, the most widely studied sRNA, bind to messenger RNAs causing destabilization of transcription machinery or degradation of transcript1–3. MicroRNAs are biomarkers and mediators of numerous human diseases such as cancers4,5, cardiovascular disease6, and autoimmunity7,8. With sRNA sequencing, awareness of other types of sRNAs is increasing, including sRNAs of microbial origin in human plasma9–11. These microbial sRNAs may act as signaling molecules which mediate human-microbiota interaction10.

Numerous studies demonstrated altered microbiome in early and established RA12–15. However, specific pathogens with putative rationale for driving disease through citrullination, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis16,17 and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans12, are unchanged or decreased in RA versus controls in several microbiome studies18,19, including one of the largest in RA to date14. Other microbes such as Prevotella copri13 and Lactobacillus salivarius14 are increased in RA patients, but it is unclear how these microbes may affect RA.

Microbial sRNAs may be virulence factors to evade host immunity. For example, a tRNA-derived fragment (tDR) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa inhibits human bronchial epithelial cell mitogen activated protein (MAP) kinases leading to decreased IL-8 and neutrophil recruitment to the lung, enabling chronic infection.20 Similarly, other microbial sRNAs from several human periodontal pathogens inhibit Jurkat T cell IL-5, IL-13 and IL-15 expression.21 The fungus, Botrytis cinerea, transfers sRNAs to the host plant targeting multiple genes such as MAPK1 and MAPK2, decreasing plant immune function and enhancing infection susceptibility.22 Because microbial sRNAs may alter host cellular function, plasma microbial sRNAs may represent an effector compartment of the human microbiota. Thus, characterization of microbial sRNAs is needed.

The study objective was to determine if plasma microbial sRNAs are altered in RA patients, associated with disease measures, and altered by drug treatment.

Methods

Study populations

The cross-sectional component of the study included 165 RA patients and 90 controls frequency-matched for age, race, and sex7,23–25. Recruitment and study procedures were previously described23. All subjects were >18 years of age, and RA patients met American College of Rheumatology 1987 classification criteria26. Control subjects did not have RA or other inflammatory disease.

The longitudinal study component included 70 RA patients before starting methotrexate, adalimumab, or tocilizumab and after 6 months of treatment. The patients were recruited as part of Treatment Efficacy and Toxicity in Rheumatoid Arthritis Database and Repository (TETRAD) (NCT#01070121) from nine academic centers as described previously27. Patients were >18 years of age and met American College of Rheumatology 1987 classification criteria26. Patients who also had systemic lupus erythematosus, juvenile arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, hepatitis C infection, or were currently pregnant or lactating were excluded. Both studies were approved by each respective university Institutional Review Board (ID# 000567, 150544), and all subjects gave written informed consent.

Clinical and laboratory information

Clinical and laboratory measurements were collected as previously described23,27. RA disease activity was determined by 28-joint count disease activity score (DAS28) using erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). ESR was measured by the clinical laboratory at each center. Disease duration was defined as years since diagnosis in the cross-sectional cohort study, and years since symptom onset in the longitudinal cohort. DAS28 improvement was defined as a decrease in DAS28>0 units after six months of treatment. EULAR response was defined as a decrease in DAS28≥0.6 units and endpoint DAS28≤ 5.1 units28 after six months of treatment.

Small RNA sequencing and genome alignments

Total RNA was extracted from plasma using Total RNA Purification Kits (Norgen). Libraries were prepared using TruSeq Small RNA Library Preparation Kits (Illumina). Libraries were size selected Pippin Prep and sequenced using Illumina HiSeq 3000 by the Vanderbilt Technologies for Advanced Genomics.

High quality reads were demultiplexed using Illumina’s CASAVA 1.8 pipeline and 3’ adapters were trimmed using Cutadapt29. Reads <16-nt after adapter trimming were discarded. TIGER analytical pipeline11 assigned reads as human and microbial. High quality reads were first aligned to the human genome (Hg19) and curated mature miRNAs (miRBase v21, http://www.mirbase.org), tRNAs (UCSC tRNA database GtRNAdb v2.0, http://gtrnadb.ucsc.edu/) and rRNAs (http://archive.broadinstitute.org/cancer/cga/rnaseqc_download and NCBI database), permitting 1 mismatch using Bowtie (v1.1.2). Human miRNAs were permitted offset −2 to 2-nt and other human sRNAs were counted with ≥90% overlap except for lncRNA-derived RNAs and rRNAs which required perfect match ≥90% overlap. Remaining reads ≥20-nt not aligned to the human genome were aligned using Bowtie permitting 0 mismatches to 1) representative genomes of 207 human microbiome bacteria, 8 fungi, 167 environmental bacteria, and 57 bacterial genomes with literature-based relationship to RA; 2) tRNAs in GtRNAdb database; and 3) rRNA transcripts in SILVA database (https://www.arb-silva.de). sRNAs mapping to bacterial or fungal genomes as above were designated “Microbial”. Remaining reads were categorized “Other”.

Reads per million reads were analyzed as individual sRNAs, and microbial genome counts using DESeq2. The cross-sectional component was adjusted for age, race, sex and batch. In all NGS differential expression analyses for each separate module (human microbiome, environmental bacteria, fungi, and RA-related bacteria) the Benjamini-Hochberg method30 was used to adjust for multiple comparisons with false discovery rate (FDR) at 5%. Thus, <5% of significantly altered features after FDR-adjustment are expected to be false positive.

PCR validation of select microbial sRNAs

Total RNA was extracted from plasma as described above except that a cocktail of three sRNA mimic standards were added after initial lysis step. RNA was polyadenylated and converted to first strand cDNA using an oligo-dT adaptor primer and standard kits (Quanta Biosciences). Custom sRNA forward primers were designed for microbial sRNAs of interest. PerfeCTa Universal PCR primer was used as reverse primer (Quanta Biosciences). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using PerfeCTa SYBR green (Quanta Biosciences). The cross-sectional component used 96-well format with triplicate samples, and the longitudinal component used 384-well format with quadruplicate samples, and Bio-Rad CFX96 and CFX384 instruments, respectively. A sRNA mimic standard curve was run in each plate to convert Cts to molar concentrations.

General Statistics

Descriptive statistics were calculated as median with interquartile range for continuous variables and frequency and proportions for categorical variables. Wilcoxon’s rank sum tests were used to compare continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-square test to compare categorical variables. The association between clinical variables and total microbial reads, genome counts and individual sRNAs which were significantly altered in RA verses controls after FDR-adjustment were compared by Wilcoxon’s rank sum tests, Spearman correlation, and linear regression without adjusting for multiple comparisons. Geometric mean was used to present fold differences for skewed data. Data were analyzed using R version 3.6.1 and IBM SPSS version 25. The tRNA schematic was prepared using http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/31,32.

Results

This study included two components: a cross-sectional component including RA and control subjects, and an independent longitudinal component including RA patients before and after starting a new disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD).

Cross-sectional study

Subject characteristics

In the cross-sectional study of RA patients (N=165) and control subjects (N=90), median age was 54 and 53 years, respectively, and the majority were Caucasian and female (online supplementary Table S1). Among RA patients, median disease duration was 3 years, 72% were seropositive and disease activity was moderate (median DAS28 score=3.91). Most RA patients were taking methotrexate (71%), and 20% were taking an anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agent.

Total microbial sRNAs: RA vs control and relationship to RA disease features

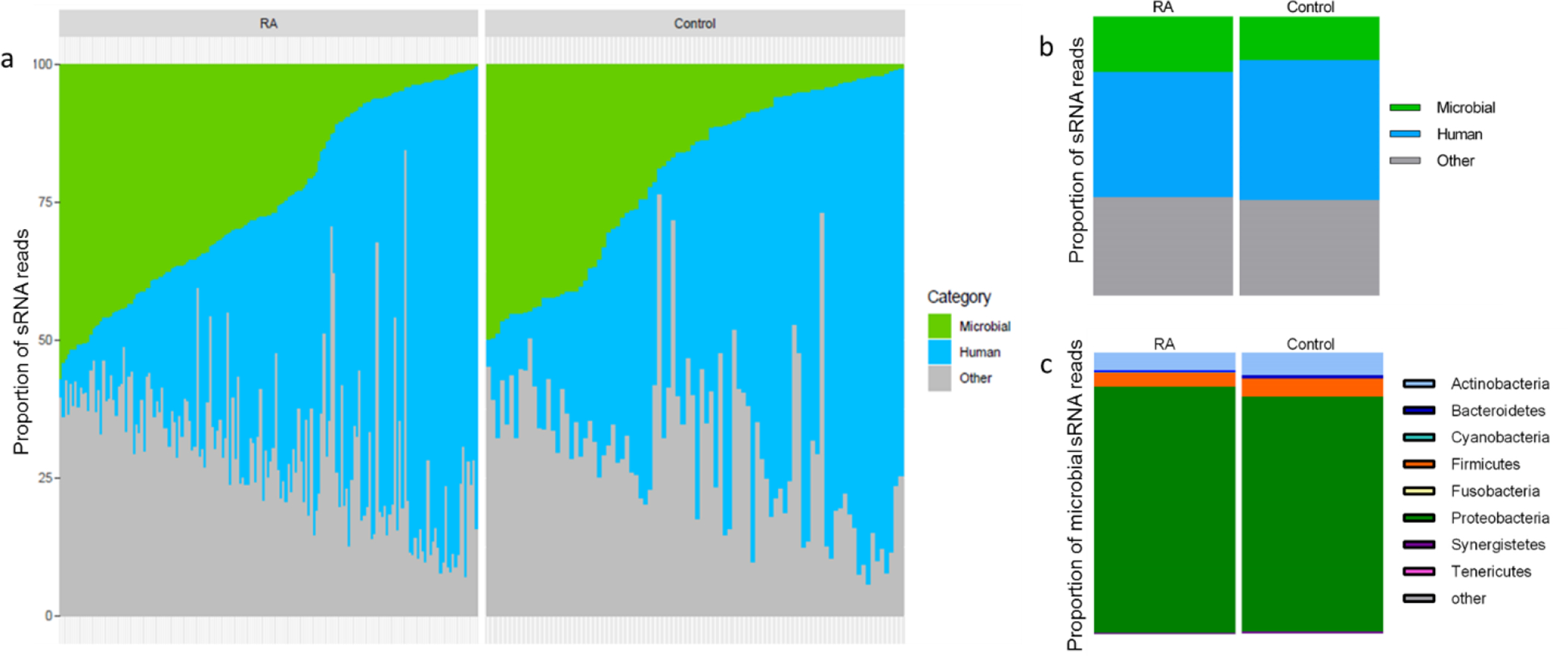

The proportion of plasma sRNAs mapping perfectly to microbial genomes was approximately 20% for RA and 16% for control subjects, and not significantly different (P=0.08) (Figure 1a and b). Most microbial sRNAs (>80%) mapped to the phylum Proteobacteria (Figure 1c). No RNA control samples had very few microbial sRNA sequences (online supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of microbial sRNAs in RA patients and control subjects. Proportion of microbial, human and other plasma sRNAs in individual patients with RA and control subjects (a) and based on geometric mean (b). Approximately 20% of plasma sRNAs from RA patients and 16% from control subjects align to microbial genomes (P=0.08). The category designated as “other” (a, b) refers to sRNAs which were too short, or did not map to the human or microbial genomes or databases evaluated.

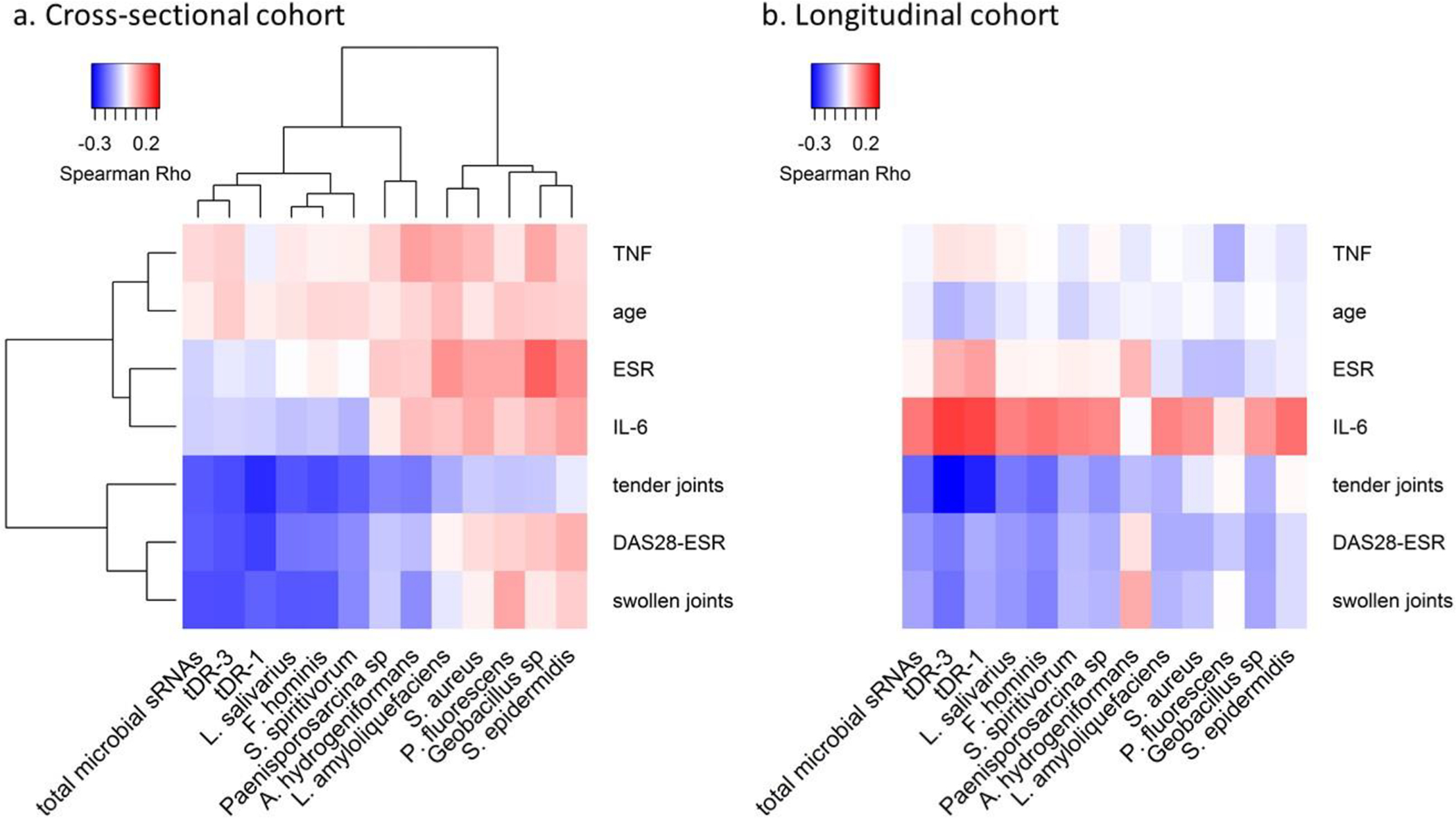

Among RA patients, tender joint count (Rho= −0.22, p=0.006), swollen joint count (Rho= −0.23, p=0.003), and DAS28 score (Rho= −0.21, P=0.008) (Figure 2a, online supplementary Table S2) were inversely associated with total microbial sRNAs. The proportion of microbial sRNAs was not different based on seropositivity (P=0.41) or correlated with ESR, interleukin 6 (IL-6) or TNF alpha (Figure 2a, online supplementary Table S2).

Figure 2.

Relationship between clinical features and microbial genome counts, and microbial sRNAs which are altered in RA patients compared to control subjects. Panel a includes data from the cross-sectional cohort. Panel b includes data from the longitudinal cohort. tDR-1 and tDR-3 are qPCR-based plasma concentrations. The inverse association between the tDR-1 and tDR-3 sequences and total proportion of plasma microbial sRNAs with DAS28 score and tender and swollen joint count is similar in the cross-sectional and longitudinal cohorts. DAS28 score = disease activity score based on 28 joint count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, ESR= erythrocyte sedimentation rate, IL-6= serum interleukin 6, TNF-α= serum tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Microbial sRNA sequences: RA vs control and relationship to disease features

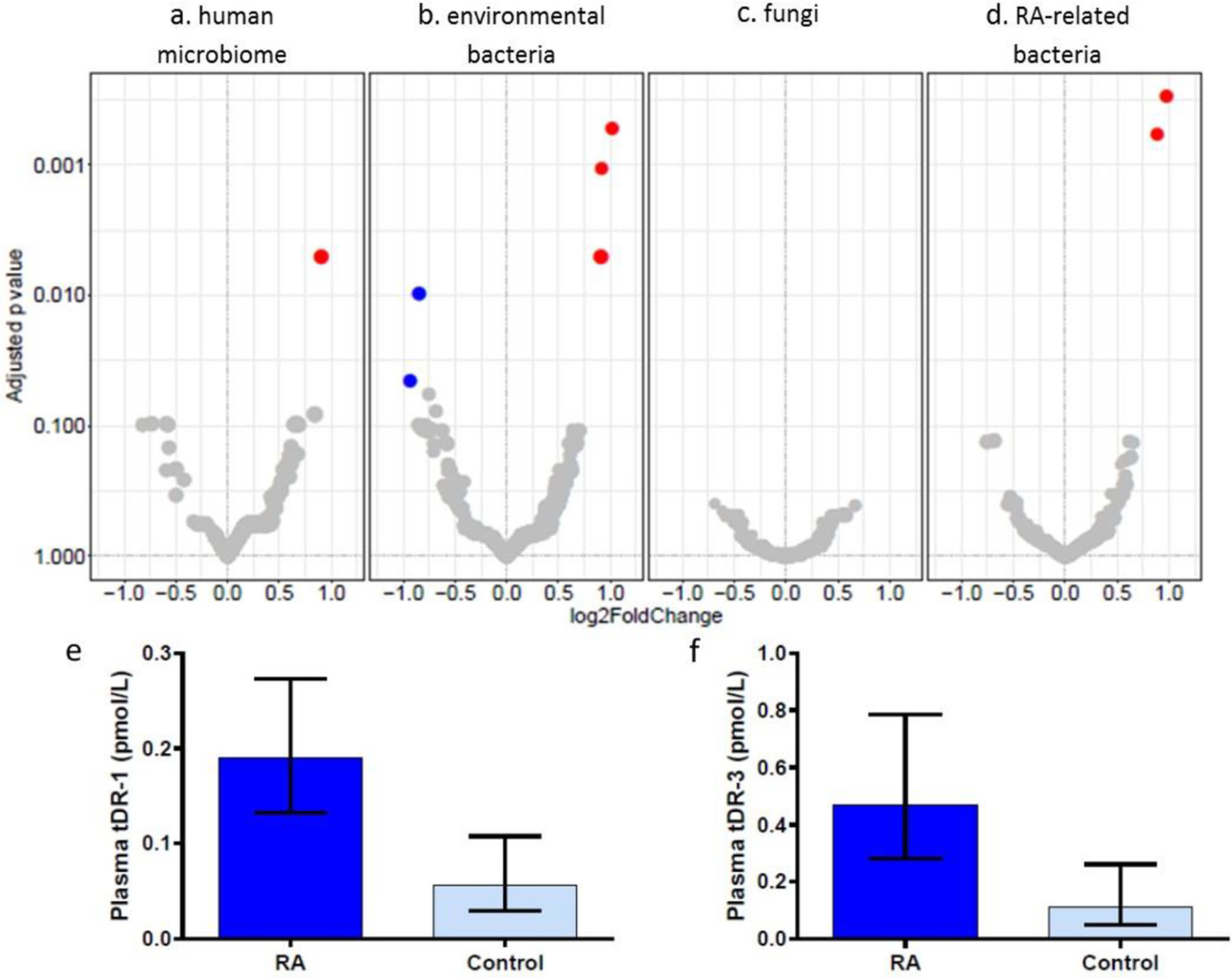

Individual microbial sRNA sequence counts aligning to any of four modules: human microbiome, environmental bacteria, fungal, and literature-derived RA-related human microbiome (Figure 3a–d) were compared between RA and control subjects. After FDR adjustment three microbial sRNAs were significantly increased approximately 2-fold and two microbial sRNAs were significantly decreased approximately 2-fold in RA compared to control subjects (Table 1, online supplementary Tables 3S–6S).

Figure 3.

Differential expression of microbial sRNAs in RA versus control subjects. Volcano plots of differential expression of individual microbial sRNA sequences in RA versus control subject plasma. Red dots indicate increased expression in RA plasma and blue dots indicated decreased expression in RA versus control subject plasma. Larger dot indicates increased relative abundance of the sRNA sequence. The plots include sRNAs aligning to microbial genomes of the human microbiome (a), environmental bacteria (b), fungi (c), and bacterial genomes with literature-based relationship to RA (d). qPCR-based validation of tDR-1 (e) and tDR-3 (f) presented as geometric mean and 95% confidence intervals.

Table 1.

Significantly altered microbial sRNAs in RA vs Control subjects (cross-sectional cohort)

| Modules to which the sRNA maps | Fold difference | P adj | |

|---|---|---|---|

| tDR-1: GCACCCGTAGCTCAGCTGGA | Microbiome, environmental, RA-associated | 2.02 | 0.0005 |

| tDR-2: GCACCCGTAGCTCAGCTGGATA | Microbiome, environmental, RA-associated | 1.89 | 0.001 |

| tDR-3: GCACCCGTAGCTCAGCTGGATAGAGCACCAGACT | Microbiome, environmental | 1.88 | 0.005 |

| rDR-1: GAGATTAGCGGAACGCTCTGGAAAGTGC | Environmental | −1.80 | 0.01 |

| rDR-2: TTCAAGGCCGAGAGCTGATGACGAGTT | Environmental | −1.91 | 0.046 |

tDR= microbial transfer RNA derived RNA. rDR= microbial ribosomal RNA derived RNA. Fold difference comparing RA versus control subjects assessed by DESeq2 adjusted for age, race, sex, batch (FDR=0.05) from NGS data for each module.

The three microbial sRNAs which were increased among RA patients are tRNA-derived RNAs (tDRs) derived from the same tRNA encoding for arginine (Table 1, online supplementary Figure S2). Two of these sequences are tRNA fragments size of microRNAs (tDR-1= GCACCCGTAGCTCAGCTGGA and tDR-2= GCACCCGTAGCTCAGCTGGATA), and the third sequence is a 5’ tRNA half (tDR-3= GCACCCGTAGCTCAGCTGGATAGAGCACCAGACT). These three tDRs align mainly to phylum Proteobacteria and class Alphaproteobacter, such as the genera Brevundimonas, Brucella, Bartonella, and Porphyrobacter. tDR-1 and tDR-3 were also significantly enriched in RA vs control plasma when measured by qPCR (Figure 3e and f; tDR-1: 3.36-fold, P=0.0006; tDR-3: 4.13-fold, P=0.008). tDR-2 was not assayed by qPCR due to concern for overlap of primer specificity with tDR-1. The two plasma microbial sRNA sequences which were decreased in RA compared to controls (Table 1) are derived from rRNAs, however, were not significantly decreased in RA patients by qPCR. Thus, only tDR-1 and tDR-3 were evaluated further.

Plasma concentrations of tDR-1 and tDR-3 were significantly inversely associated with DAS28 score, tender joint count, and swollen joint count, but not markers of inflammation, such as ESR, IL-6 and TNFα (Figures 2a, online supplementary Table S2).

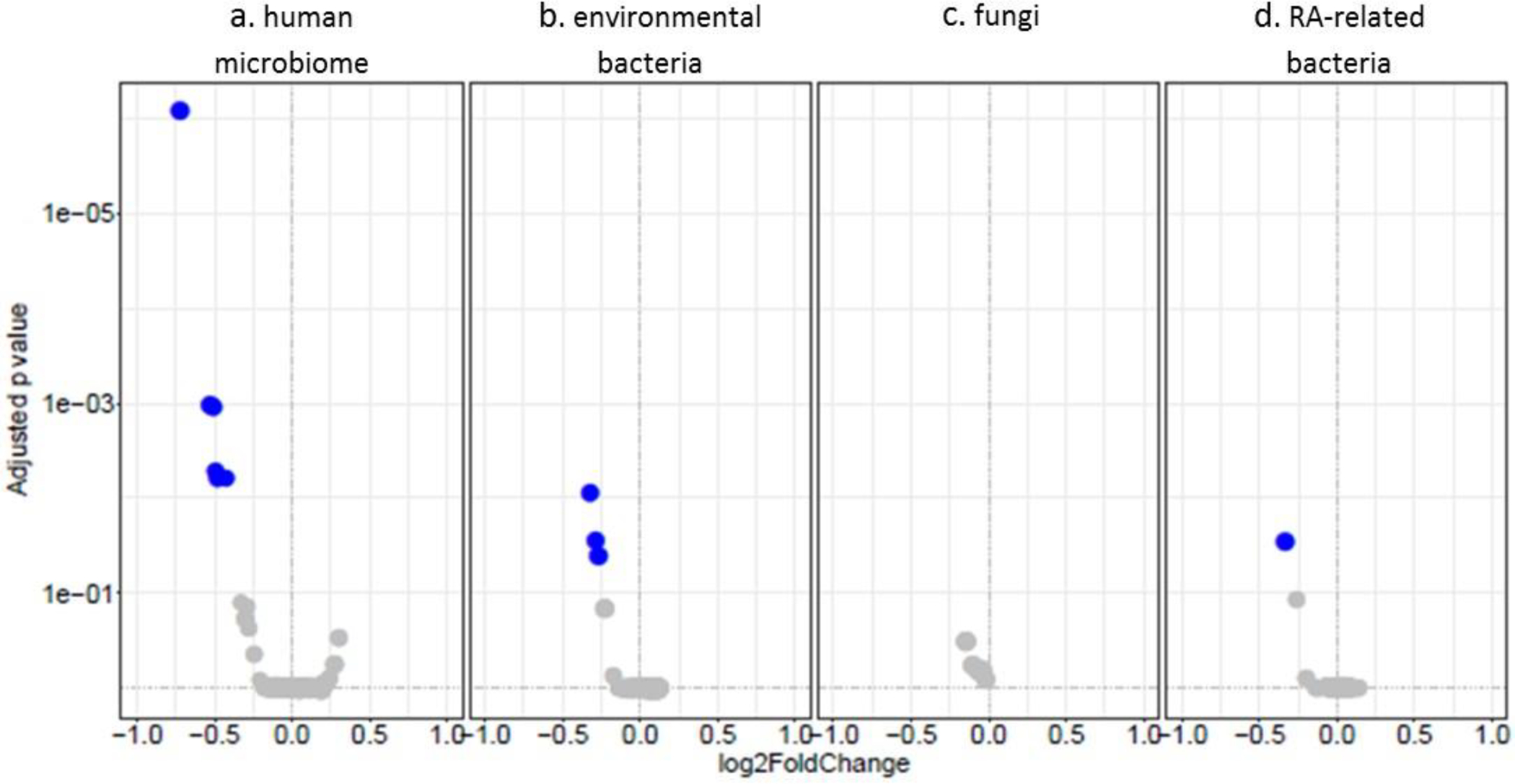

Microbial genome counts: RA vs controls and relationship to disease features

Microbial sRNAs were assigned to genome counts of microbes within the four modules (Figure 4). In the human microbiome module, genome counts of Anaerobaculum hydrogeniformans, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, Paenisporosarcina sp., Facklamia hominis, and Sphingobacterium spiritivorum were significantly decreased in RA patients compared to controls after FDR-adjustment (Table 2, online supplementary Table S7). In the environmental module, genome counts of Lentibacillus amyloliquefaciens, Geobacillus sp., and Pseudomonas fluorescens were significantly decreased in RA patients compared to controls after FDR-adjustment (Table 2, online supplementary Table S8). Fungal genome counts were not significantly altered (online supplementary Table S9). In the RA-associated microbial genomes module, genome counts of Lactobacillus salivarius were significantly decreased in RA patients compared to control subjects after FDR-adjustment (Table 2, online supplementary Table S10).

Figure 4.

Volcano plots of differential expression of genome alignment counts of plasma sRNAs in RA vs Control subject plasma. The plots include genome counts of representative microbes of the human microbiome (a), environmental bacteria (b), fungi (c), and RA-related bacteria (d).

Table 2.

Microbial genome counts which are altered in RA versus control subjects (cross-sectional cohort)

| Fold difference RA vs Control | Padj | |

|---|---|---|

| Microbiome | ||

| Anaerobaculum hydrogeniformans | −1.65 | 8.60E-07 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | −1.44 | 0.001 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | −1.42 | 0.001 |

| Paenisporosarcina sp. | −1.41 | 0.005 |

| Facklamia hominis | −1.40 | 0.006 |

| Sphingobacterium spiritivorum | −1.34 | 0.006 |

| Environmental | ||

| Lentibacillus amyloliquefaciens | −1.26 | 0.009 |

| Geobacillus sp. | −1.22 | 0.03 |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | −1.21 | 0.04 |

| RA-specific | ||

| Lactobacillus salivarius | −1.26 | 0.03 |

Fold difference of microbial genome counts comparing RA versus control subjects assessed by DESeq2 adjusted for age, race, sex, batch (FDR=0.05) from NGS data for each module.

Microbial genome counts of F. hominis and L. salivarius were significantly inversely associated with DAS28 score, tender and swollen joint count, but not with ESR, plasma IL-6 or TNFα (Figure 2a, online supplementary Table S11).

Longitudinal Study – Before and after DMARD

Subject characteristics

In the longitudinal study RA patients (N=70) had a median age of 54 years and the majority were Caucasian and female. Median disease duration was 4.2 years, 61% were seropositive, and median disease activity was moderate (DAS28=4.91). A total of 24 started methotrexate, and 23 each started adalimumab and tocilizumab (online supplementary Table S12).

Total microbial sRNAs: drug effect and response

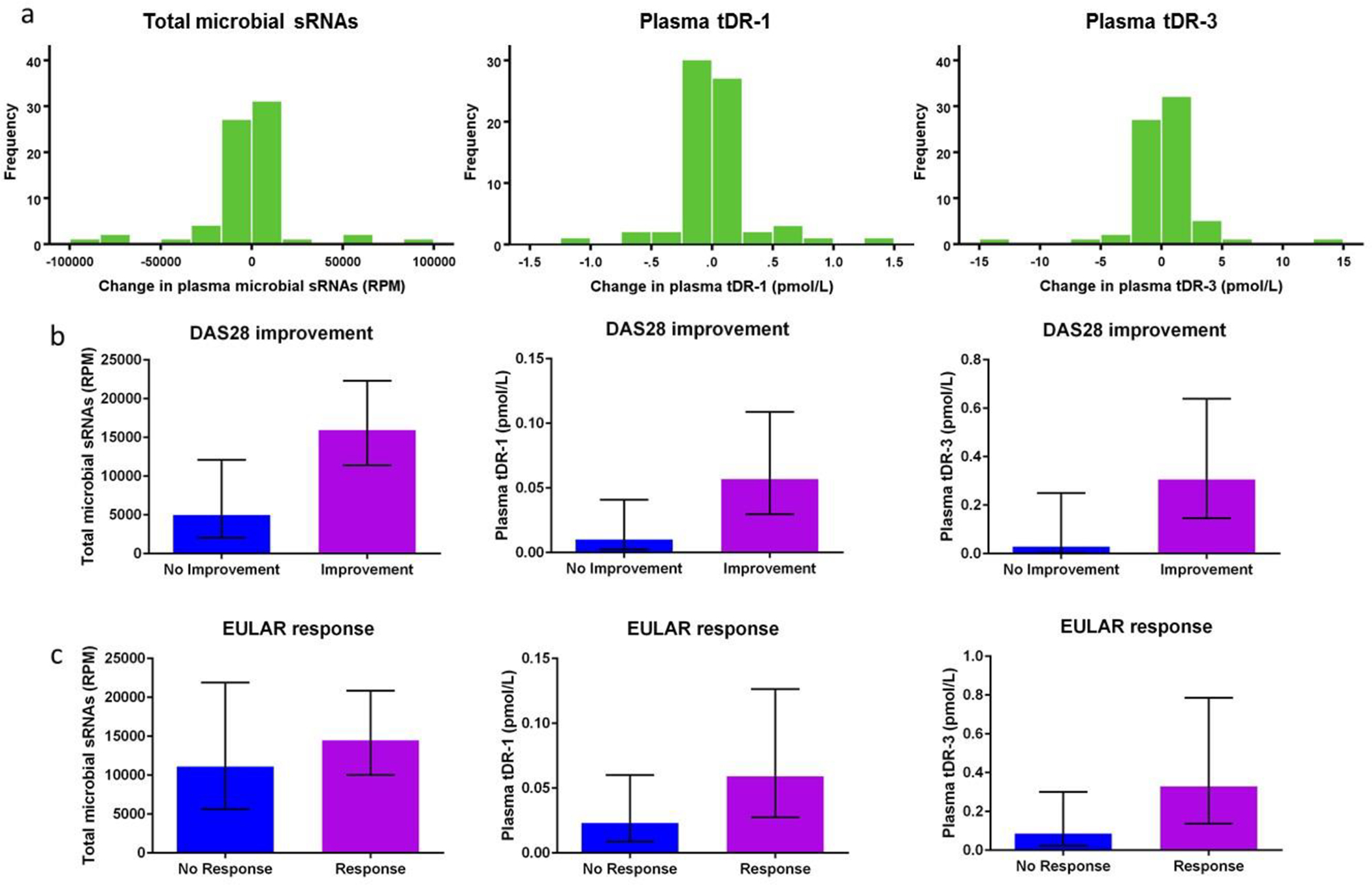

Total microbial sRNA reads were not significantly altered in RA before compared to 6 months after starting a new DMARD (P=0.57) (Figure 5a). However, baseline microbial sRNA reads were 3.19-fold higher at baseline (P=0.004) among patients whose DAS28 score improved after initiation of the index drug compared to those whose score was unchanged or worsened (Figure 5b). Baseline microbial sRNA reads were non-significantly higher among those met moderate-to-good EULAR response criteria compared to did not (1.3-fold higher among responders, P=0.27) (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Microbial sRNAs and relationship to DMARD use. No significant change in total plasma microbial sRNAs, plasma tDR-1, or plasma tDR-3 concentrations was observed after initiation of a new DMARD (a). Among RA patients whose DAS28 score improved after initiation of a new DMARD, total plasma microbial sRNAs, plasma tDR-1, and plasma tDR-3 concentrations were all significantly increased compared to those did not improve (b). Among RA patients who met EULAR response criteria 6 months after initiation of a new DMARD, total plasma microbial sRNAs, plasma tDR-1, and plasma tDR-3 concentrations were not significantly increased compared to those did not achieve EULAR response (b). Histograms of the change in microbial sRNAs six months after initiation of a new disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) are presented (a). Bar plots are presented as geometric mean with 95% confidence intervals (b, c).

Microbial sRNA sequences: drug effect and response

Plasma tDR-1 and tDR-3 concentrations did not significantly change after 6-months of new DMARD treatment (Figure 5a, change in tDR-1 P=0.44; change in tDR-3 P=0.47). However, similar to total microbial sRNA reads, baseline tDR-1 and tDR-3 concentrations were significantly higher (tDR-1: 5.6-fold, P=0.02; and tDR-3: 10.7-fold, P=0.03) among patients whose DAS28 score improved after drug initiation compared to those whose DAS28 score remained unchanged or worsened (Figure 5b). A similar trend for moderate to good EULAR response criteria was observed but not significant (tDR-1: 2.5-fold, P=0.08; and tDR-3: 3.9-fold, P=0.08) (Figure 5c).

Other individual microbial sRNA sequences and microbial genome counts were not significantly altered before versus after treatment after FDR-adjustment (all Padj>0.05).

Replication of cross-sectional study findings within the longitudinal cohort

Similar to the cross-sectional study, total plasma microbial sRNA abundance (Rho=−0.19, P=0.02) and tDR-1 (Rho=−0.28, P=0.001), and tDR-3 (Rho=−0.33, P<0.001) were all significantly inversely associated with tender joint count within the longitudinal cohort (Figure 2b, online supplementary Table S2). A similar trend for association with DAS28 score and swollen joint count was observed for these features but not all were statistically significant. As in the longitudinal cohort, total plasma microbial sRNAs, tDR-1 and tDR-3 were not associated with TNFα concentration or ESR (Figure 2a and b, online supplementary Table S2). The significant inverse relationship between tender joint count and genome counts of F. hominis and L. salivarius was also found in the longitudinal cohort (Figure 2b, online supplementary Table S13).

Functional prediction of tDR-1 and tDR-3

Based on seed region binding to mRNA 3’UTR (online supplementary Table S14), tDR-1 and tDR-3 are predicted to downregulate “antimicrobial response, cell death and survival and inflammatory response” gene network (online supplementary Table S15), and the “B cell activating factor signaling” canonical pathway (online supplementary Table S16). Thus, these tDRs are predicted to downregulate pathways related to host immune function.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first study to examine microbial sRNAs in RA patients. There were several major findings. In RA patients, a higher proportion of plasma microbial sRNAs was associated with lower RA disease activity. Several microbial tDRs closely structurally related were significantly increased among RA patients and were also associated with lower measures of disease activity. Genome counts of 10 microbes were modestly but significantly decreased among RA patients compared to control subjects, and higher genome counts of several of these were also modestly associated with lower measures of disease activity. Although the findings were modest, the cross-sectional and longitudinal RA studies were concordant for several findings: measures of disease activity were inversely associated with the proportion of plasma microbial sRNAs, plasma tDR-1 and tDR-3 concentrations, and proportion of sRNA sequences aligning to L. salivarius and F. hominis.

Few studies have investigated disease associations and biologic significance of microbial sRNAs within human circulation. Despite different methods, studies report similar microbial sRNA landscape to our study with Proteobacteria a commonly identified bacterial phylum9,10. In plasma from 3 healthy controls, 3 colon cancer and 3 ulcerative colitis patients, about 20% of sRNAs aligned to microbial genomes with Proteobacteria most abundant bacterial phylum based on alignment to microbial genomes10. Another study assembled non-human sRNA reads from 3 human plasma samples as contigs for annotation, an approach which would not be applicable to many processed sRNAs, nevertheless contigs aligning to Proteobacteria represented the most abundant phylum9.

The source of circulating microbial sRNAs is not known. We and others33 hypothesize several ways that microbial sRNAs may enter plasma. One possibility is that plasma microbial sRNAs correspond with components of the human microbiota. In this study and others9,10,34 Proteobacteria was the most abundant bacterial phylum represented by plasma microbial sRNAs, but is not abundant in most human microbiome studies35. However, Proteobacteria is the most abundant phylum in gut mucosal biopsies36, and plasma microbiome studies37. Thus, microbes in close contact with mucosal barriers may be most likely to cross a leaky barrier and contribute to circulating microbial sRNAs. There are likely other sources of microbial sRNAs beyond the gut.

The function of microbial sRNAs in humans is only starting to be evaluated and to date there is little information. Some believe these microbial sRNAs are purposefully delivered to the host via extracellular vesicles along with virulence factors to promote bacterial survival20. For example, sRNAs are abundant in bacterial outer membrane vesicles from Pseudomonas aeruginosa20 and these outer membrane vesicles were able to deliver sRNAs to human bronchial epithelial cells. Moreover, a tDR, abundant in P. aeruginosa outer membrane vesicles, downregulated the LPS-stimulated MAPK signaling pathway within human cells to suppress innate immune response. Thus, microbial sRNAs may help the microbe evade the human immune system, but little is known currently.

The three microbial tDRs enriched among RA patients and inversely associated with disease activity were derived from the same tRNA. The length of the tDRs suggest they were processed as typical tRNA fragments (tDR-1 and tDR-2) and halves (tDR-3) as found in bacterial outer membrane vesicles20, 21,38 and within cells and body fluids of humans39–42. Microbial tDR processing and function is not fully understood. In mammalian cells, angiogenin is increased during cellular stress response and cleaves some tRNAs, forming halves which can cause global inhibition of translation43 and inhibition of apoptosome formation44 to promote cell survival. The tRNA fragments, which are of similar length to microRNAs, may function like microRNAs by using Argonaute proteins45, or enabling rapid cell division by binding to and loosening hairpin loops of mRNA encoding for ribosomal proteins46.

The consideration that sRNAs could alter host immune response is intriguing given our finding that higher proportion of plasma microbial sRNAs is associated with lower measures of disease activity in two separate cohorts. Moreover, as we demonstrated in the longitudinal cohort, microbial sRNA alterations present among RA patients were not changed by DMARDs. Rather, total microbial sRNAs in the plasma and certain sequences may indicate that a patient will improve with a new DMARD. Microbial sRNAs could alter host immune response, as suggested by target predictions, and ability to respond to DMARDs. Alternatively, these may be a marker of host immune function. Further studies will be dedicated to testing this hypothesis.

Limitations

This study has limitations. Observed clinical associations with microbial sRNAs are very modest. Differences in plasma sRNA classes and individual sequences are relative to the total sRNAs sequenced. Contamination could lead to plasma microbial sRNA measurements47, but we found few microbial sRNAs in no-RNA controls. Lastly, because most microbial sRNAs in human plasma are rDRs and tDRs, sequences are often conserved across similar species. Thus, one microbial sRNA may align to multiple genomes.

Supplementary Material

Key messages:

What is already known about this subject?

Microbial small RNAs are found in human plasma and can alter host immune function.

What does this study add?

We found that the composition of microbial small RNAs is altered in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared to control subjects and related to measures of disease activity.

While the microbial small RNAs are not altered by three common disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, greater abundance of microbial small RNAs and specific small RNAs were associated with better drug response.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

It is possible that microbial small RNAs may act as an effector compartment of the human microbiota and potentially open new avenues of drug therapy for patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases. However, further studies will be necessary to understand the role of microbial sRNAs in RA.

Funding:

This work is supported by Veterans Health Administration CDA IK2CX001269, Arthritis Foundation Delivering on Discovery grant, Alpha Omicron Pi, NIH Grants: P60AR056116, and CTSA award UL1TR000445 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Competing interests Dr. Ormseth reports grants from Veterans Health Administration/ Office of Research and Development, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Wu reports grants from Alpha Omicron Pi, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Zhao has nothing to disclose. Dr. Allen has nothing to disclose. Dr. Solus has nothing to disclose. Dr. Sheng has nothing to disclose. Dr. Guo has nothing to disclose. Dr. Ye has nothing to disclose. Ms Ramirez has nothing to disclose. Dr. Bridges has nothing to disclose. Dr. Curtis has nothing to disclose. Dr. Vickers has nothing to disclose. Dr. Stein reports grants from NIH, during the conduct of the study.

TETRAD Investigators: Dr. Bingham has nothing to disclose. Dr. Levesque reports other from Abbvie, outside the submitted work. Dr. Moreland has nothing to disclose. Dr. Nigrovic has nothing to disclose. Dr. O’Dell has nothing to disclose. Dr. Shadick reports Brigham and Women’s Hospital grant funding from Mallinckrodt, Bristol Myers Squibb, Crescendo Biosciences, Sanofi-Regeneron, Lilly and AMGEN; consulting for Bristol Myers Squibb <5K. Dr. St Clair has nothing to disclose.

Previous presentation of work Components of this work were presented in oral format at the 2018 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting and poster format at the 2017 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting and as such the abstracts were published in an online supplement of Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Ethical approval The Institutional review board of Vanderbilt University Medical Center approved this study. Additionally, Institutional review boards of University of Alabama at Birmingham, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Duke University, Johns Hopkins University, North Shore Medical Center, Stanford University, University of Colorado Denver, University of Nebraska, and University of Pittsburgh approved the prospective component of the study.

Data sharing statement Data will be made available on request to the corresponding author (Michelle J Ormseth).

Patient and Public Involvement Patients and/or public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

References

- 1.Baek D, Villen J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP, Bartel DP. The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature. 2008;455(7209):64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116(2):281–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136(2):215–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwarzenbach H, Nishida N, Calin GA, Pantel K. Clinical relevance of circulating cell-free microRNAs in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11(3):145–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montani F, Bianchi F. Circulating Cancer Biomarkers: The Macro-revolution of the Micro-RNA. EBioMedicine. 2016;5:4–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navickas R, Gal D, Laucevicius A, Taparauskaite A, Zdanyte M, Holvoet P. Identifying circulating microRNAs as biomarkers of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Cardiovasc Res. 2016;111(4):322–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ormseth MJ, Solus JF, Vickers KC, Oeser AM, Raggi P, Stein CM. Utility of Select Plasma MicroRNA for Disease and Cardiovascular Risk Assessment in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. The Journal of rheumatology. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Churov AV, Oleinik EK, Knip M. MicroRNAs in rheumatoid arthritis: altered expression and diagnostic potential. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(11):1029–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beatty M, Guduric-Fuchs J, Brown E, et al. Small RNAs from plants, bacteria and fungi within the order Hypocreales are ubiquitous in human plasma. BMC genomics. 2014;15:933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang K, Li H, Yuan Y, et al. The complex exogenous RNA spectra in human plasma: an interface with human gut biota? PloS one. 2012;7(12):e51009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen RM, Zhao S, Ramirez Solano MA, et al. Bioinformatic analysis of endogenous and exogenous small RNAs on lipoproteins. J Extracell Vesicles. 2018;7(1):1506198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konig MF, Abusleme L, Reinholdt J, et al. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans-induced hypercitrullination links periodontal infection to autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(369):369ra176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scher JU, Sczesnak A, Longman RS, et al. Expansion of intestinal Prevotella copri correlates with enhanced susceptibility to arthritis. eLife. 2013;2:e01202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Zhang D, Jia H, et al. The oral and gut microbiomes are perturbed in rheumatoid arthritis and partly normalized after treatment. Nat Med. 2015;21(8):895–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez-Oliva I, Paropkari AD, Saraswat S, et al. Dysbiotic Subgingival Microbial Communities in Periodontally Healthy Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(7):1008–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wegner N, Wait R, Sroka A, et al. Peptidylarginine deiminase from Porphyromonas gingivalis citrullinates human fibrinogen and alpha-enolase: implications for autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2010;62(9):2662–2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mikuls TR, Thiele GM, Deane KD, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis and disease-related autoantibodies in individuals at increased risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2012;64(11):3522–3530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scher JU, Ubeda C, Equinda M, et al. Periodontal disease and the oral microbiota in new-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2012;64(10):3083–3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mankia K, Cheng Z, Do T, et al. Prevalence of Periodontal Disease and Periodontopathic Bacteria in Anti-Cyclic Citrullinated Protein Antibody-Positive At-Risk Adults Without Arthritis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e195394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koeppen K, Hampton TH, Jarek M, et al. A Novel Mechanism of Host-Pathogen Interaction through sRNA in Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(6):e1005672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi JW, Kim SC, Hong SH, Lee HJ. Secretable Small RNAs via Outer Membrane Vesicles in Periodontal Pathogens. J Dent Res. 2017;96(4):458–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiberg A, Wang M, Lin FM, et al. Fungal small RNAs suppress plant immunity by hijacking host RNA interference pathways. Science. 2013;342(6154):118–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chung CP, Oeser A, Raggi P, et al. Increased coronary-artery atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis: relationship to disease duration and cardiovascular risk factors. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2005;52(10):3045–3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ormseth MJ, Lipson A, Alexopoulos N, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue is associated with cardiometabolic risk and the metabolic syndrome in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis care & research. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ormseth MJ, Chung CP, Oeser AM, et al. Utility of a novel inflammatory marker, GlycA, for assessment of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity and coronary atherosclerosis. Arthritis research & therapy. 2015;17:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1988;31(3):315–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ormseth MJ, Yancey PG, Solus JF, et al. Effect of Drug Therapy on Net Cholesterol Efflux Capacity of High-Density Lipoprotein-Enriched Serum in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(9):2099–2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Gestel AM, Prevoo ML, van ‘t Hof MA, van Rijswijk MH, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Development and validation of the European League Against Rheumatism response criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. Comparison with the preliminary American College of Rheumatology and the World Health Organization/International League Against Rheumatism Criteria. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1996;39(1):34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulte JH, Marschall T, Martin M, et al. Deep sequencing reveals differential expression of microRNAs in favorable versus unfavorable neuroblastoma. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(17):5919–5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate - a Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J Roy Stat Soc B Met. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gruber AR, Lorenz R, Bernhart SH, Neubock R, Hofacker IL. The Vienna RNA websuite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Web Server issue):W70–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lorenz R, Bernhart SH, Honer Zu Siederdissen C, et al. ViennaRNA Package 2.0. Algorithms Mol Biol. 2011;6:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fritz JV, Heintz-Buschart A, Ghosal A, et al. Sources and Functions of Extracellular Small RNAs in Human Circulation. Annu Rev Nutr. 2016;36:301–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeri A, Courtright A, Reiman R, et al. Total Extracellular Small RNA Profiles from Plasma, Saliva, and Urine of Healthy Subjects. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Human Microbiome Project C. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486(7402):207–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang MS, Poles J, Leung JM, et al. Inferred metagenomic comparison of mucosal and fecal microbiota from individuals undergoing routine screening colonoscopy reveals similar differences observed during active inflammation. Gut Microbes. 2015;6(1):48–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shukla SK, Cook D, Meyer J, et al. Changes in Gut and Plasma Microbiome following Exercise Challenge in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). PloS one. 2015;10(12):e0145453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han EC, Choi SY, Lee Y, Park JW, Hong SH, Lee HJ. Extracellular RNAs in periodontopathogenic outer membrane vesicles promote TNF-alpha production in human macrophages and cross the blood-brain barrier in mice. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2019:fj201901575R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Godoy PM, Bhakta NR, Barczak AJ, et al. Large Differences in Small RNA Composition Between Human Biofluids. Cell Rep. 2018;25(5):1346–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li S, Xu Z, Sheng J. tRNA-Derived Small RNA: A Novel Regulatory Small Non-Coding RNA. Genes (Basel). 2018;9(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sobala A, Hutvagner G. Small RNAs derived from the 5’ end of tRNA can inhibit protein translation in human cells. RNA Biol. 2013;10(4):553–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ormseth MJ, Solus JF, Sheng Q, et al. The Endogenous Plasma Small RNAome of Rheumatoid Arthritis. ACR Open Rheumatology. 2020;2(2):97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ivanov P, Emara MM, Villen J, Gygi SP, Anderson P. Angiogenin-induced tRNA fragments inhibit translation initiation. Molecular cell. 2011;43(4):613–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saikia M, Jobava R, Parisien M, et al. Angiogenin-cleaved tRNA halves interact with cytochrome c, protecting cells from apoptosis during osmotic stress. Molecular and cellular biology. 2014;34(13):2450–2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ren B, Wang X, Duan J, Ma J. Rhizobial tRNA-derived small RNAs are signal molecules regulating plant nodulation. Science. 2019;365(6456):919–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim HK, Fuchs G, Wang S, et al. A transfer-RNA-derived small RNA regulates ribosome biogenesis. Nature. 2017;552(7683):57–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heintz-Buschart A, Yusuf D, Kaysen A, et al. Small RNA profiling of low biomass samples: identification and removal of contaminants. BMC Biol. 2018;16(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.