INTRODUCTION

Luminal distention is a common pathological characteristic in all mechanical [8,25,66,68,69] and functional [14,52] obstructive bowel disorders (OBD). Abdominal distention is also frequently encountered in functional bowel disorders (FBD), such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and constipation [1,9]. In fact, nearly 70% of IBS patients have abdominal distention [9], which is largely due to luminal retention of gas and feces in the bowel [1,44,65]. In these lumen distention-associated conditions, abdominal pain is a main symptom [15,25,61]. However, mechanisms for abdominal pain in lumen distention are incompletely understood. There is no specific analgesic medication for lumen distention-associated abdominal pain. Thus, opioids are often used for analgesic treatment in these conditions [61]. However, repeated use of opioids leads to opioid addiction and further dysfunctions such as opioid-induced constipation and narcotic bowel syndrome [27,36]. There is great need to uncover mechanisms of lumen distention-associated abdominal pain and identify therapeutics to specifically target pain in these conditions.

Visceral hypersensitivity (VHS) is a well-recognized mechanism of abdominal pain in gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, such as IBS [5,19,23,38,73]. Recent pre-clinical studies found that VHS is also present in OBD [21,31,45,46]. Both nociceptive and antinociceptive systems are involved in keeping visceral sensitivity in normal state [33], and alterations of any components in the two systems may lead to VHS [3,6,26,27]. Primary nociceptive afferent neurons located in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) play a critical role in the development of VHS in the gut, with DRG neuronal hyper-excitability well demonstrated in IBS and OBD [3,5,24,45]. However, whether anti-nociceptive system is involved in VHS and pain in lumen distention-associated disorders is not well understood. As the primary anti-nociceptive system, endogenous opioids and their receptors are distributed widely throughout the body, including peripheral sensory nerves of the gut [33]. There are at least three types of opioid receptors, μ, δ, and κ receptors (MOR-1, DOR-1, and KOR-1, respectively). Recent evidence suggests that a MOR-dependent endogenous opioidergic tone exists on colonic extrinsic nerve activity, as administration of peripherally restricted opioid antagonists i.e. naloxone methiodide increases visceral sensitivity in healthy and inflamed animals [6,26,33,39,57]. Moreover, decreased production of endogenous opioids may contribute to VHS [32].

Probiotics have been increasingly used for FBD and OBD [20,64]. Recent studies showed that Lactobacillus may have beneficial effects in attenuating VHS and abdominal pain [54,61,71]. In previous studies, we found that obstruction resulted in a marked reduction of L. reuteri abundance in the distended colon in rats [29]. In addition, visceral sensitivity is highly augmented in obstruction with increased excitability of the DRG neurons projecting to the distended colon [31,45]. In the present study, we determined whether colonic recolonization of L. reuteri normalizes visceral sensitivity in lumen distention and investigated the molecular mechanisms involved in the analgesic effect. We hypothesized that mechanical stress in lumen distention leads to down-regulation of opioid receptor expression in the colon, which contributes to VHS in obstruction. We further hypothesized that recolonization of L. reuteri helps to normalize visceral sensitivity in obstruction by restoring expression of opioid receptors in the colon.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Ethics Statement:

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) approved all animal procedures. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) guidelines were followed to minimize pain in animals.

Bacterial strains and culture:

L. reuteri MM2–3 (PTA-4659) and L. reuteri MM4–1A (PTA-6475) human derived strains were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, USA). L. reuteri (4–1) and L. reuteri (5–1) strains were isolated in our lab from the stomach and colon, respectively, of a naïve male Sprague Dawley rat (9 week old). Briefly, the gastric and colon mucosa was scraped off aseptically and homogenized using micro tube homogenizer in sterile PBS. Serial dilutions were then plated on MRS agar plates (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) and incubated in anaerobic jars for 24 h. White spherical colonies were then picked and screened for L. reuteri by PCR using specific 16S primers LR_IDL52F: ACCTGATTGACGATGGATCACCAGT and LB_IDL03R: CCACCTTCCTCCGGTTTGTCA, as previously described [37]. Ability of isolates to produce reuterin was evaluated as described before [59]. Isolates were further confirmed by sequencing the full length 16S gene PCR product (UniF: GCTTAACACATGCAAG, UniR: CCATTGTAGCACGTGT, Product length- 1200 bp) [53]. The sequence was analyzed using the microbial nucleotide blast tool (NCBI, Bethesda, USA) and isolates matched with L. reuteri DSM 20016 strain (99% sequence identity). The natural antibiotic resistance of Lactobacillus strains to 100 μg/ml of Kanamycin and Vancomycin was also confirmed by culture.

All L. reuteri strains were grown in MRS broth (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) with 1% Oxyrase for broth (Oxyrase, Mansfield, USA) and 100 μg/ml of Kanamycin and Vancomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cultures were started with 1% inoculum and grown for 20 h. Colony forming units (CFU) were calculated by plating serial dilutions on MRS agar. L. reuteri (4–1) reached the concentration of 2.5 × 109 CFU/ml, whereas L. reuteri (5–1) reached the concentration of 2.65 × 109 CFU/ml by 20 h.

Induction of partial colon obstruction in rats:

Male Sprague-Dawley rats at 8 −10 weeks of age (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, IN) were used in the study. Rats were housed in a controlled environment (temperature, 23°C ± 2; Humidity 55% ± 10; 12-h light/dark cycle) and allowed free access to food and water throughout the study. Partial colon obstruction was surgically induced as previously described [43,45,66]. Briefly, after rats were anesthetized, a medical-grade silicon band (3 mm wide and 20 mm long) was placed around the distal colon by midline laparotomy. Sham control rats also underwent the laparotomy as above, but the band was removed immediately after being placed. Obstruction was maintained for 7 days. When treating the rats with L. reuteri, oral gavage of 2×107 CFU in PBS /g body weight was administrated. While treating rats with human isolates, L. reuteri MM2–3 and L. reuteri MM4–1A were mixed at the above concentration before gavage. Similarly, the two rat isolates L. reuteri (4–1) and L. reuteri (5–1) were mixed before administration. Treatment was started 2 days prior to the induction of obstruction or sham surgery and continued until the day before euthanasia. Body weight, food and water intake were recorded every other day throughout the experiment.

Quantification of L. reuteri copy number in colon feces:

L. reuteri specific 16S rRNA primers, LR- f: ACCGAGAACACCGCGTTATTT; LR-r: CATAACTTAACCTAAACAATCAAAGATTGTCT (Tm: 59°C, R2:0.994) were used to calculate total copy number in colon feces by qPCR [28]. L. reuteri specific16S rRNA regions were amplified using 5–50 ng fecal DNA as template, 25 pmol/μl specific primers and 1X power SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA) in 20 μl final reaction volume. All PCRs were performed in duplicates using the StepOne plus Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA). The PCR conditions were: 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing for 30 s at respective Tm temperature, and 72 °C for 45 s. Melting curve analysis was carried out at the end.

The standard curve for L. reuteri quantification was generated by serial dilution of pJet plasmid (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA USA) in which 16S rRNA target sequence from L. reuteri 6475 (ATCC) was cloned. Copy number for the standard curve was calculated by formula: Number of copies = [amount (ng)* A] / [length (bp) * 1×109 * 650] where A was the Avogadro constant (6.02× 1023). The total bacterial 16S rRNA gene copy number /mg of sample was calculated using equation: Copy number / mg = [Mean Copy number × Volume of extracted DNA taken (μl)] / [Total volume of extracted DNA (μl) × mg of sample used for DNA isolation).

Measurements of referred visceral hyperalgesia:

Assessment of visceral sensitivity by measuring visceromotor response to colorectal distension with a balloon is not feasible during colon obstruction. However, as visceral pain has a unique feature that a painful sensation is found in a referred somatic region (i.e. lower abdomen as referral zone for colon), we measured referred visceral hyperalgesia in our OB model using the Von Frey filament (VFF) test as described elsewhere [23,31,45]. In brief, rats were shaved in the lower abdomen, and a 3 × 3 cm2 area of the lower abdomen along the midline was marked for VFF testing. Rats were kept in a translucent cage (3.5 × 7.0 × 3.5 in3) for 30 minutes for pretest adaptation and then for VFF testing. The Von Frey filaments for each of the forces (0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, and 8.0 g of force) were applied to the marked area 10 times, each for 2 seconds at a 10-second interval, in an ascending order. The numbers of withdrawal responses including abdominal retraction, licking or scratching of the filament, immediate movement or jumping were recorded. In some cases, rats were injected with peripheral opioid antagonist naloxone-methiodide 5mg/kg (i.p.) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) before the 30 min pretest adaptation time. After the adaptation time, VFF test was performed as described above.

Labeling of colon-specific sensory neurons in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) for patch clamp studies:

Colon-specific neurons in DRG were labeled by injecting 1,19-dioleyl-3,3,39,3-tetramethylindocarbocyanine methanesulfonate (DiI; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) into the colon wall as described previously [10,44,45]. In brief, after placing an obstructive band around the colon by a midline laparotomy, 5 μL of DiI (50 mg/mL in methanol) was injected into the muscle layer of the gut wall at 6–8 sites of the colon segment 3–4 cm oral to obstruction in OB rats or to the middle colon in sham rats. Isolation of DRG neurons for patch-clamp recordings were done 7–10 days after DiI injection.

Isolation of DRG neurons:

DRG neuron isolation was performed as described previously [10,44,45,74]. Briefly, rats were decapitated and spinal cord was transferred to ice-cold oxygenated fresh dissecting solution [130mM NaCl, 5mM KCl, 2mM KH2PO4, 1.5mM CaCl2, 6mM MgSO4, 10mM glucose, and 10mM HEPES, pH 7.2 (305 mOsm)]. While colon-projecting DRG neurons may originate in either thoracolumbar or lumbosacral segments [24, 31], we focused on the thoracolumbar (T13 to L2) DRG neurons in the present study as we did previously using our OB model [21, 45]. This is because our pilot study found that colon projecting DRG neurons from either thoracolumbar (i.e. T13 to L2) or lumbosacral segments (i.e. L6 to S3) demonstrated increased excitability in OB. The thoracolumbar DRGs (T13–L2) were isolated and digested in dissecting solution containing 1.5 mg/mL collagenase D (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and 1.2 mg/mL trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) at 34.5°C for 1.5 hours. After washing samples in enzyme-free solution, single-cell suspension was obtained by trituration using flame polished glass pipettes. For patch clamp, cells were plated onto acid-cleaned glass coverslips in normal external solution containing 130mM NaCl, 5mM KCl, 2mM KH2PO4, 2.5mM CaCl2,1mM MgCl2,10mM HEPES, and 10mM glucose, pH 7.4 (295–300 mOsm). For DRG culture, cells were suspended in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1X antibiotic-antimycotic solution, 1X non-essential amino acids (Gibco, Life technologies, Waltham, USA).

Patch-clamp analysis:

Recording pipettes with resistance of 4 to 7 MV and were filled with pipette solution containing 100mM KmeSO3, 40mM KCl, and 10mM HEPES, pH 7.3 (290mOsm). DiI-labeled DRG neurons of about 30 μm in diameter were accepted for analysis if they had a stable resting membrane potential (RP) (0.245 mV) and displayed overshooting action potentials (APs). DiI-labeled colon-specific DRG neurons (bright red) were identified using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with rhodamine filter (excitation 546 mm, barrier filter at 580 mm). Whole-cell current and voltage were recorded by a Dagan 3911 patch-clamp amplifier (Dagan, Minneapolis, MN) as described [10,44,45]. Capacitive transients were corrected using capacitive cancellation circuitry on the amplifier that yielded the whole-cell capacitance and access resistance. Up to 90% of the series resistance was compensated electronically. The currents were filtered at 2 to 5 kHz and sampled at 50 or 100 ms per point. Data were analyzed using pCLAMP 9.2 (Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA).

Sample collection, RNA isolation, and qRT-PCR analysis:

To obtain colonic mucosa/submucosa (MS) and muscularis externa (ME) tissues, colon segments 2 cm oral to the obstruction site were collected and opened along the mesenteric border. The MS and ME layers were separated by microdissection as described previously [40,42,44,66]. To isolate colon specific DRG neurons for gene expression studies, cholera toxin B subunit (CTB, 40 μg in 20 μL PBS per rat) was injected to the musculature of the mid colon (6 sites). After 7~10 days, rats were euthanized, and DRGs of T13 to L2 were isolated. The CTB-labeled colon specific DRG neurons were isolated by laser capture micro-dissection [21, 45]. To determine if OB alters expression of nociceptive and anti-nociceptive mediators in the lower abdominal wall where visceral sensation in the colon is referred to, we also dissected rectus abdominis muscle with skin tissue in the lower abdomen for molecular studies.

Total RNA was extracted from tissue samples using the Qiagen RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). 500 ng of total RNA was reverse-transcribed with the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and qRT-PCR was carried out in Applied Biosystems 7000 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The assay IDs for TaqMan detection of rat OPRM1: Rn01430371_m1, OPRD1: Rn00561699 _m1, OPRK1: Rn01448892_m1, TRPV1:Rn00583117_m1, NGF: Rn01533872_m1, BDNF: Rn01484928_m1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). 18S rRNA was used as endogenous control (Part no. 4352930E, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Western blotting:

Colonic ME and MS samples were homogenized on ice in RIPA buffer (Cell signaling, Danvers, USA) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 2 and 3 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). After centrifuging at 12,000 g at 4°C for 15 minutes, the supernatant was collected and resolved by a standard immunoblotting method. Equal quantities (20~100 μg) of total protein were run on pre-made 4–12% Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). OPRM1 (MOR-1) antibody (1:2000) was from Thermo-fisher scientific (Austin, TX) (Cat# PA3–203, Lot# ra224670). OPRD1 (DOR-1) antibody (1:500) was purchased from Life span biosciences (Seattle, WA, USA) (Cat# LS-C383200, Lot# 126591). OPRK1 (KOR-1) antibody (1:200) was purchased from Santa Cruz biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA) (Cat# Sc-374479, Lot# K2816). β-actin antibody (1:5000, Sigma, St. Louis, USA) was used as loading control. The protein band detection was performed using Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

Immunofluorescence staining:

Immunofluorescence staining was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, 4-μm thick colon sections of sham and obstruction rats. After deparaffinization and rehydration, sections were subjected to antigen retrieval in Tris-EDTA Buffer (10mM Tris Base, 1mM EDTA Solution, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 9.0). Cells were permeabilized using 0.2% Tween-20 (Fisher scientific) and blocking was done with 1x TBS containing 10% goat serum and 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). Sections were treated with 0.25% Sudan black to reduce auto fluorescence as described before [18]. Primary antibodies were diluted in 1x TBS containing 2% BSA and sections were incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing slides with 1X TBS thrice, sections were incubated with pre-adsorbed fluorescent conjugated respective secondary antibodies (Thermo Fischer scientific, Austin, USA). Slides were mounted using Vectashield mounting medium (Vector laboratories, Burlingame, USA) and images were taken using Revolve fluorescent microscope from Echo labs (Echo, San Diego, USA). Anti-OPRM1 antibody (1:100) was purchased from Thermo Fischer scientific (Austin, USA) and Anti-Hu antibody (1:250) was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Fluorescence intensity was quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). A region of interest (ROI), of fixed size was used to randomly select 5 different microscopic fields in each image. Background fluorescent intensity was also measured using identical ROI and was subtracted from positive fluorescent intensity signals. An average fluorescence intensity was obtained for each image.

Muscle bath study:

Colonic segment ~2 cm oral to the obstruction was collected in fresh carbogenated Krebs buffer (118 mM NaCl, 4.7mM KCl, 2.5mM CaCl2, 1mM NaH2PO4, 1.2mM MgCl2, 1mM D-glucose, and 25mM NaHCO3). Colonic circular smooth muscle strips of size 3 × 10 mm2 were dissected from the colon segment [45,66,67] and aligned along the circular muscle orientation in muscle baths (Radnoti Glass, Monrovia, CA) containing 10 mL carbonated Krebs solution. The muscle contractility was recorded as described before [66,67] using Grass isometric force transducers and amplifiers connected to Biopac data-acquisition system (Biopac Systems, Goleta, CA, USA). Initial equilibration of muscle strips was done at 1 g tension for 60 min at 37 °C, and then contractile response to acetylcholine (ACh) 10−6 to10−2 M was recorded with 15 to 20 min interval. Contractility was measured in terms of the increase in area under curve (AUC) in the first 4 min of ACh stimulation against the AUC during 4 min before the addition of ACh. AUCs of each muscle strip were normalized with its cross section area using below formula: wet tissue weight (mg) / [tissue length (mm) × 1.05 (muscle density in mg/mm³)].

Statistical analysis:

Graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla, CA, USA). Results are represented as means ± standard mean error unless stated. Comparison between the sham and OB samples were done using two tailed unpaired t-test assuming unequal variance. Multiple comparisons were done using two-way ANOVA (followed by Turkey’s test and p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS:

Validation of L. reuteri colonization in rat colon

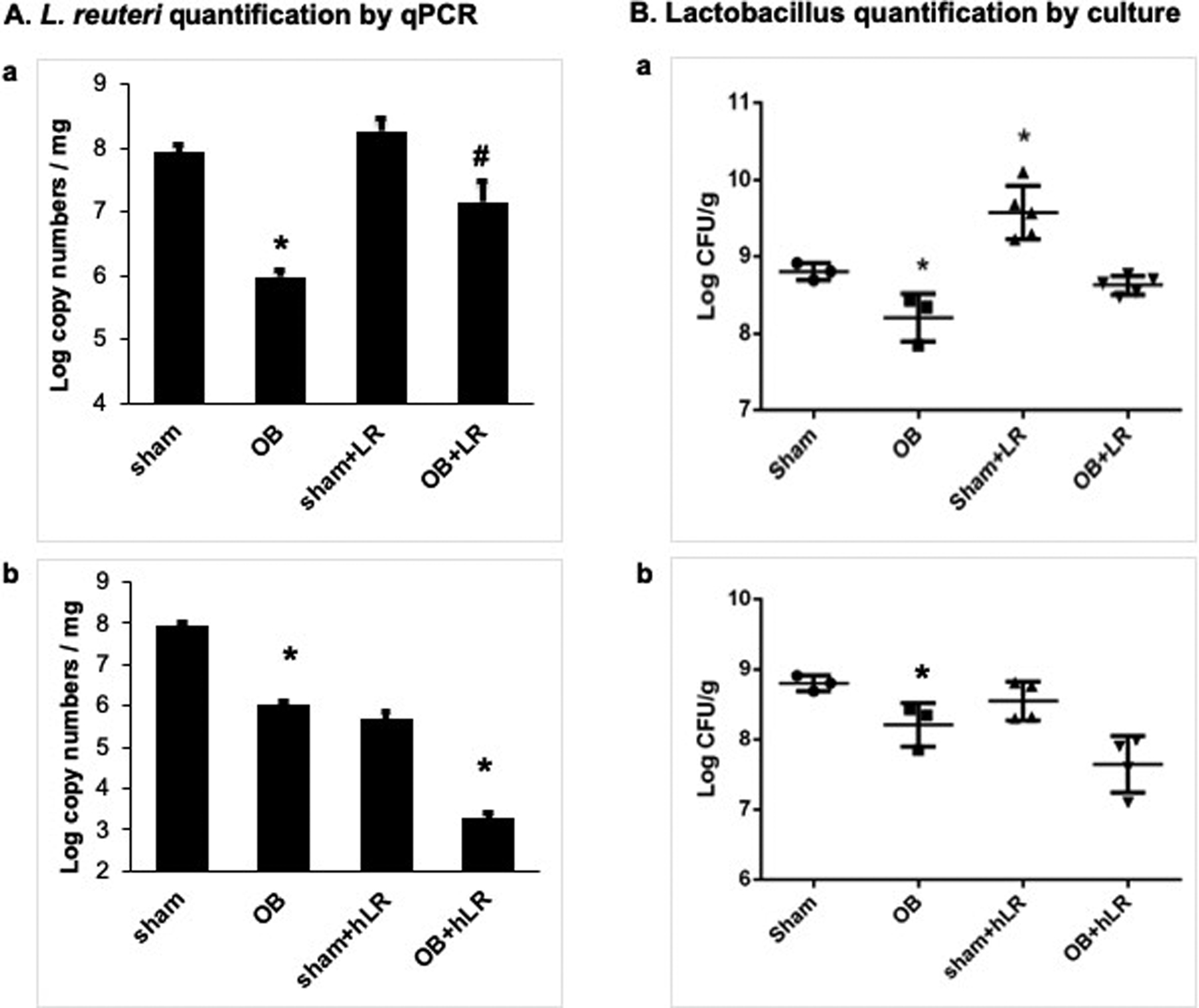

Quantification of total L. reuteri 16S copy number by qRT-PCR revealed that L. reuteri abundance decreased by two orders of magnitude in OB colon feces [Log (5.98 ± 0.11) copies mg−1, n=4], compared to sham control [Log (7.94 ± 0.10) copies mg−1, n= 5, Fig 1 Aa and Ab, p<0.05]. This was confirmed by quantification of total viable lactobacillus in sham and OB colon feces showing significantly decreased lactobacillus abundance in OB rats [sham: Log (8.80 ± 0.11) CFU g−1; OB: Log (8.21 ± 0.31) CFU g−1, n= 3, p<0.05, Fig 1 Ba and Fig Bb). To achieve L. reuteri re-colonization in rat colon, we compared the results after treatments with L. reuteri strains isolated from human (L. reuteri MM2–3 and L. reuteri MM4–1A) and indigenous rat strains (LR 4–1 and LR 5–1). Daily oral gavage of an equal mixture (1:1) of rat L. reuteri strains LR 4–1 and LR 5–1 at 2X107 CFU in PBS /g body weight for 9 days led to a significant increase in L. reuteri abundance in sham and OB rats. Administration of rat strains also significantly increased L. reuteri copy numbers in treated sham (Sham+LR) [Log (8.27 ± 0.20) copies mg−1, n= 5] compared to control sham (p<0.05), and significantly compensated for L. reuteri loss in treated OB rats (OB+LR) [Log (7.15 ± 0.34) copies mg−1, n= 5, p>0.05 vs sham, p<0.05 vs OB, Fig 1 Aa]. Viable Lactobacillus abundance was also significantly increased when using L. reuteri rat isolates [sham+LR: Log (9.40 ± 0.25) CFU g−1; OB+LR: Log (8.59 ± 0.15) CFU g−1, n= 3, Fig 1 Ba] (p<0.05 compared to control sham). However, 9-day treatment with a mixture of human origin strains (L. reuteri MM2–3 and L. reuteri MM4–1A) did not result in significant re-colonization of L. reuteri in rat colon. The L. reuteri copy number and viable Lactobacillus abundance did not increase either in sham or OB rats (Fig. 1 Ab and Bb). Because this represents a major species adaptation of human derived bacterial isolates, we performed our remaining experiments using L. reuteri rat-derived strains that were able to recolonize the colon in rats.

Figure 1: L. reuteri (A) and Lactobacillus (B) abundance in rat colon.

L. reuteri copy numbers were significantly decreased in OB rat colon feces compared to sham samples (A). Administration with rat L. reuteri strains (+LR) improved the L. reuteri copy numbers in treated rats (Aa). However, human L. reuteri strains (+hLR) failed to colonize in rats (Ab). Total viable lactobacillus CFU also decreased in OB colon feces compared to sham (B). Treatment with L. reuteri rat strains improved lactobacillus levels (Ba). But L. reuteri human strains had no effect on Lactobacillus levels in treated animals (Bb). N=3–5, * p<0.05 vs. sham, # p<0.05 vs. OB (Two-way ANOVA).

L. reuteri treatment improves body weight and food intake

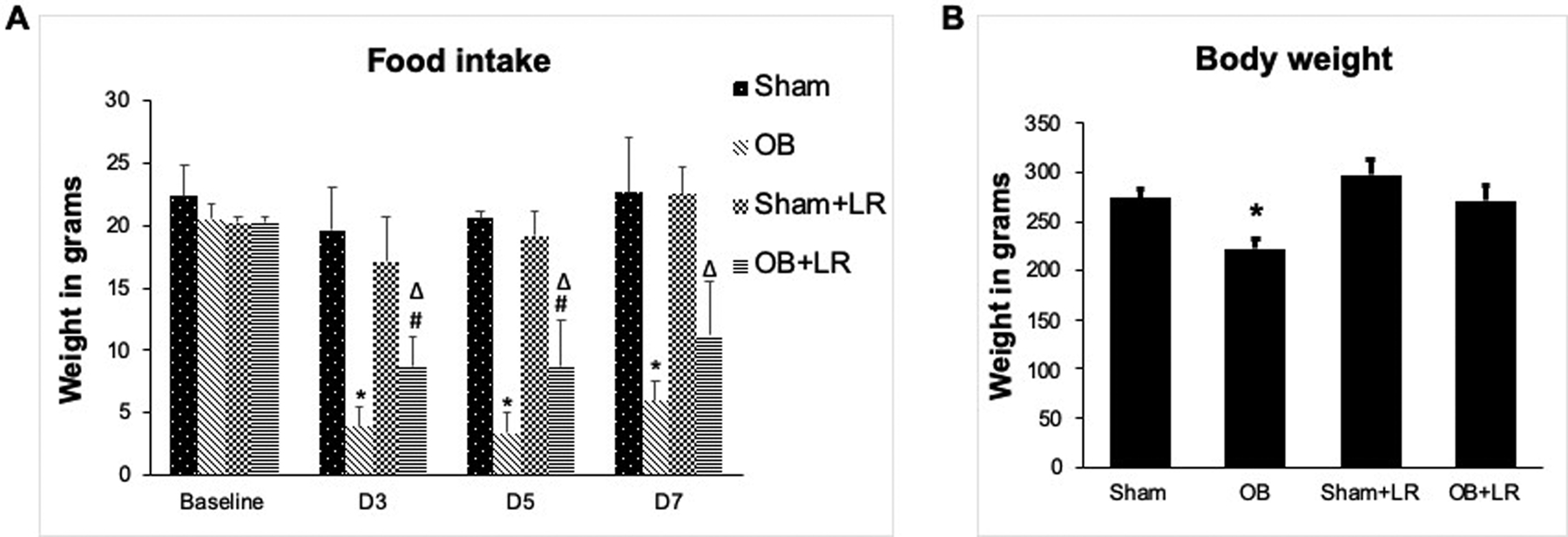

Food intake and weight change were assessed in vehicle control (PBS) and L. reuteri treated sham and OB rats throughout the experiment. We found that food intake in OB rats started to decrease on the first day after induction of obstruction, and remained significantly decreased throughout the experiment (days 3, 5, 7) (p<0.05 vs. sham, Fig 2A). However, daily gavage of L. reuteri significantly improved food intake in OB rats compared to vehicle treated OB rats (p<0.05, Fig 2A), though it did not affect food intake in sham rats. Treatment with L. reuteri also significantly improved body weight in the OB rats [OB: (222 ± 9.8) g, OB+LR: (271 ± 15.8) g, p<0.05], with no detectable effect on sham rats (Fig 2B).

Figure 2: Effect of L. reuteri treatment on food intake and body weight change.

Food intake is significantly reduced in OB rats compared to sham controls, but L. reuteri treatment significantly improved food intake in treated OB rats (A) (N=4 each). L. reuteri treatment also improved body weight in the treated OB rats (B) (N=15 for sham and OB, 6 for sham+LR and OB+LR). * p<0.05 vs. sham, # p<0.05 vs. OB, Δ p<0.05 vs. sham+LR (Two-way ANOVA).

L. reuteri treatment decreased lumen distention-associated sensory neuron hyper-excitability and referred hyperalgesia in colon obstruction

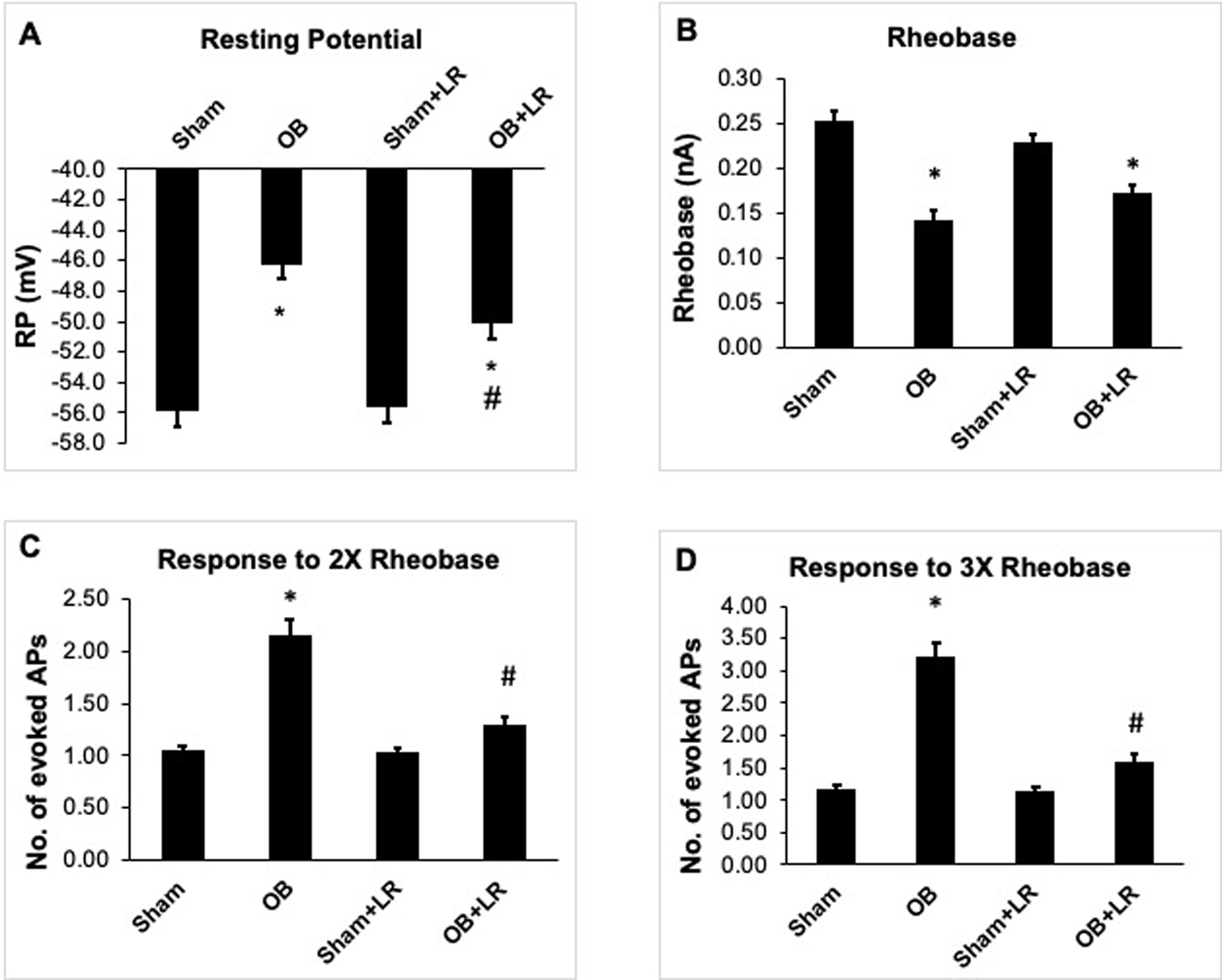

To determine if L. reuteri treatment impacts luminal distention associated VHS, we first performed patch clamp recordings of Dil labelled colon specific DRG neurons of T13 to L2 segments from control and L. reuteri treated sham and OB rats. Consistent with previous studies [44,45], cell excitability of colon specific DRG neurons was significantly increased after obstruction, with a significant decrease in resting membrane potential (RP) and rheobase, (p<0.05 Vs sham) and a significant increase in numbers of evoked action potentials (AP) (p<0.05 Vs sham, Fig 3). More importantly, L. reuteri treatment increased RP [OB+LR: −50.5(± 0.26) mV, OB: −46.2(±0.75) mV, p<0.05, Fig 3A] and rheobase [OB+LR: 0.19(±0.01) nA, OB: 0.14 (±0.01) nA, p>0.05, Fig 3B]. Furthermore, L. reuteri treatment significantly decreased the number of evoked AP in the OB rats (2X rheobase: 1.26± 0.08, 3X rheobase: 1.59±0.12, p<0.05, Fig 3C and 3D), compared to control OB rats (2X rheobase: 2.16±0.15, 3X rheobase: 3.23±0.22). L. reuteri administration did not significantly alter any tested electrophysiological properties of colon neurons in sham control rats.

Figure 3: Patch clamp study on colon-projecting dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons.

The colon-specific DRG neurons were highly excited in OB rats with decreased resting membrane potential (RP) (A) and rheobase (B) and increased number of action potentials (APs) in response to 2X rheobase stimulation (C) and 3X rheobase stimulation (D) . L. reuteri treatment partially but significantly improved resting membrane potential (RP) (A) and rheobase (B) and reduced number of action potentials (APs) in response to both 2X rheobase and 3X rheobase stimulation (C and D). N (no. of neurons/animals) = sham: 51/6, OB: 31/4, sham+LR: 28/4, OB+LR: 31/5. * p<0.05 vs. sham, # p<0.05 vs. OB (Two-way ANOVA).

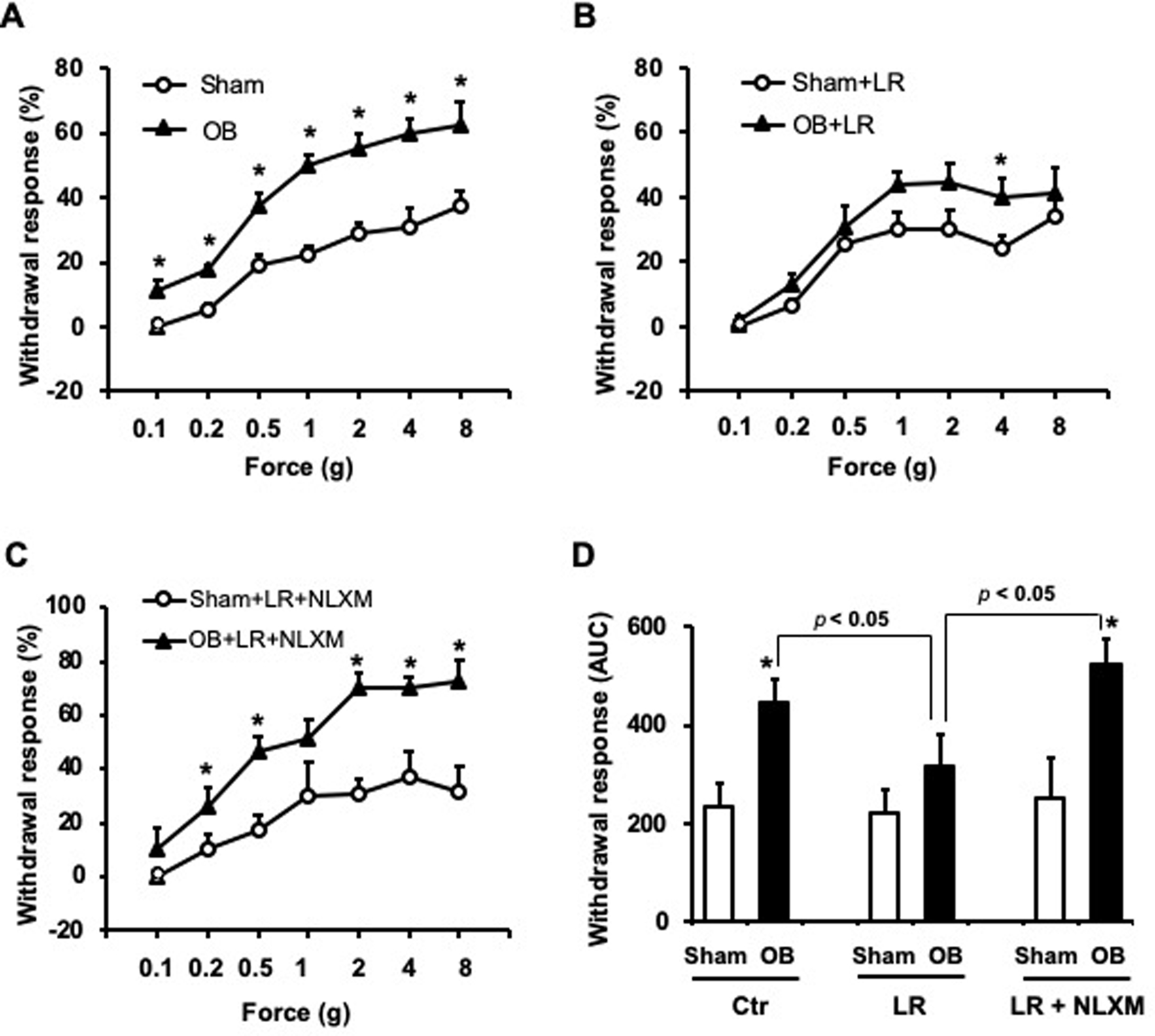

We then determined if L. reuteri treatment attenuated luminal distention associated referred hyperalgesia in OB. Consistent with previous report [45], withdrawal response to VFF stimulation was significantly increased on day 7 in OB rats compared to sham controls (Fig 4). Abdominal stimulation with 8 g VFF force evoked a withdrawal response in 37.5 (±4.5)% of the times in sham controls, but 62.5 (±6.8)% in OB rats (n=8, p<0.05, Fig 4A). However, L. reuteri treatment significantly attenuated distention-associated increase of withdrawal response in OB rats. There was no significant difference between L. reuteri- treated sham and OB rats for all the tested VFF forces (p>0.05) except for 4 g force (p=0.049, n=8) (Fig 4B). Analysis of the area under curve (AUC) also confirmed significant decreases in withdrawal response in L. reuteri treated OB rats compared to control OB rats (AUC in OB group = 444±50, AUC in OB+LR group: AUC = 316±64, p<0.05, Fig. 4D).

Figure 4: Measurements of referred visceral hyperalgesia using the von Frey filament (VFF) test.

Withdrawal response to VFF applications to the abdomen was significantly increased in obstruction on day 7 (A). N=8, * p<0.05 vs. sham (unpaired t-test). L. reuteri (LR) treatment significantly attenuated obstruction-associated referred hyperalgesia in OB rats (B). N=8, * p<0.05 vs. sham+LR (unpaired t-test). Treatment with Nalaxone methiodide (NLXM) blocked the beneficial effect of LR on the referred hyperalgesia in obstruction (C). N=7 or 8, * p<0.05 vs. sham+LR+NLXM (unpaired t-test). Analysis of area under curve (AUC) using Graphpad Prism is summarized in (D) showing the overall withdrawal responses in sham and OB rats with control (Ctr), LR and NLXM treatments. N=7 or 8, * p<0.05 vs. sham in the same treatment. Additional statistical analyses between OB control and OB+LR+NLXM vs. OB+LR were marked in the graph (D).

Expression of opioid receptors in the colon, colon-projecting DRG neurons, and somatic tissues in colon obstruction

To uncover the mechanism of action of L. reuteri in attenuating OB-associated VHS, we first determined if recolonization of L. reuteri prevented up-regulation of nociceptive mediators nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), as previous studies showed that mechanical stress-induced expression of NGF and BDNF in colon smooth muscle cells (SMC) plays a critical role in VHS in OB [21, 45]. However, we found that L. reuteri treatment did not decrease obstruction associated up-regulation of NGF and BDNF in the colon (Fig. 5A).

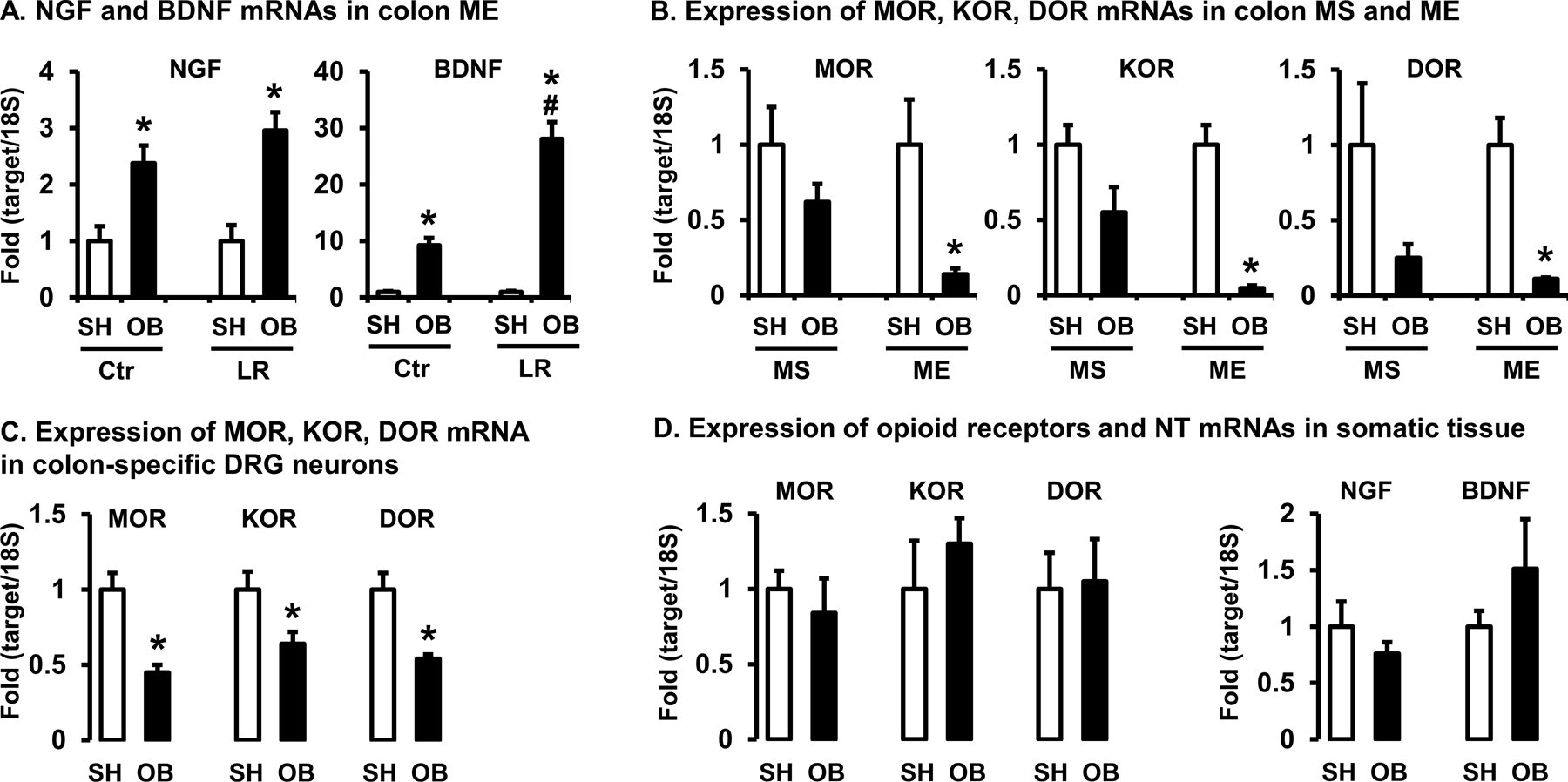

Figure 5: Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mRNA expression of neurotrophins (NT) and opioid receptors (OR) in the colon, colon-specific DRG neurons, and somatic tissues.

(A) Expression of nociceptive NTs NGF and BDNF mRNAs in colon muscularis externae (ME) of rats in sham (SH) and bowel obstruction (OB, 7 days) treated with vehicle (Ctr) or L. reuteri (LR). N=5 or 6, * p<0.05 vs. sham, # p<0.05 vs. Ctr OB (Two-way ANOVA). (B) Expression of 3 opioid receptors mRNAs (MOR-1, KOR-1 and DOR-1) in colon mucosa/submucosa (MS) and ME of sham and OB rats. All three opioid receptors expression is down-regulated significantly in ME of OB rats. (C) Expression of 3 opioid receptors mRNAs in colon-specific DRG neurons (T13 to L2) of sham and OB rats. Colon-specific DRG neurons were obtained with laser-capture micro-dissection. N=4 or 5, * p<0.05 vs. sham (Unpaired t-test). (D) Expression of ORs and NTs mRNAs in the somatic tissues (rectus abdominis muscle and skin) obtained from the lower abdomen of sham and OB rats. N=5 each group, * p<0.05 vs. sham (Unpaired t-test).

To explore the potential role of anti-nociceptive system in the analgesic effect of L. reuteri in OB, we determined expression of opioid receptors in obstruction. By quantifying MOR-1, KOR-1 and DOR-1 mRNA levels of colon mucosa/submucosa (MS) and muscularis externae (ME) collected from sham and OB rats, we found no significant change in any of the opioid receptors expression in colon MS (p>0.05, Fig 5B). However, the mRNA levels of all three opioid receptors in colon ME samples were markedly down-regulated in OB rats compared to sham controls [MOR-1: 0.14 (±0.04), KOR-1: 0.04 (±0.01), DOR-1: 0.10 (±0.007), n=5 or 6, all p<0.05 vs. sham] (Fig 5B).

We next determined whether down-regulation of opioid receptors in the distended colon occurred specifically in the primary afferent nerve innervating the colon. By laser-capture microdissection to obtain colon-specific DRG neurons, we found that the levels of MOR, KOR, and DOR mRNA expression were all significantly down-regulated in the colon-projecting DRG neurons in rats with OB compared with sham [MOR-1: 0.45 (±0.05), KOR-1: 0.64 (±0.08), DOR-1: 0.54 (±0.03), n=4 or 5 each group, all p<0.05 vs. sham] (Fig. 5C).

Considering that we assessed referred visceral hyperalgesia by applying von Frey filaments to the lower abdominal wall, we also measured mRNA expression of opioid receptors, NGF, and BDNF in the somatic area. However, there is no any significant difference of mRNA expression of MOR, KOR, and DOR in the lower abdomen between sham and OB rats (Fig. 5D). The mRNA expression of NGF and BDNF in the somatic area also is not significantly altered in bowel obstruction. These data indicate that bowel obstruction may only affect opioid receptor expression in the sensory neurons projecting to the colon.

Effect of L. reuteri treatment on mRNA and protein expression of opioid receptors in colon obstruction

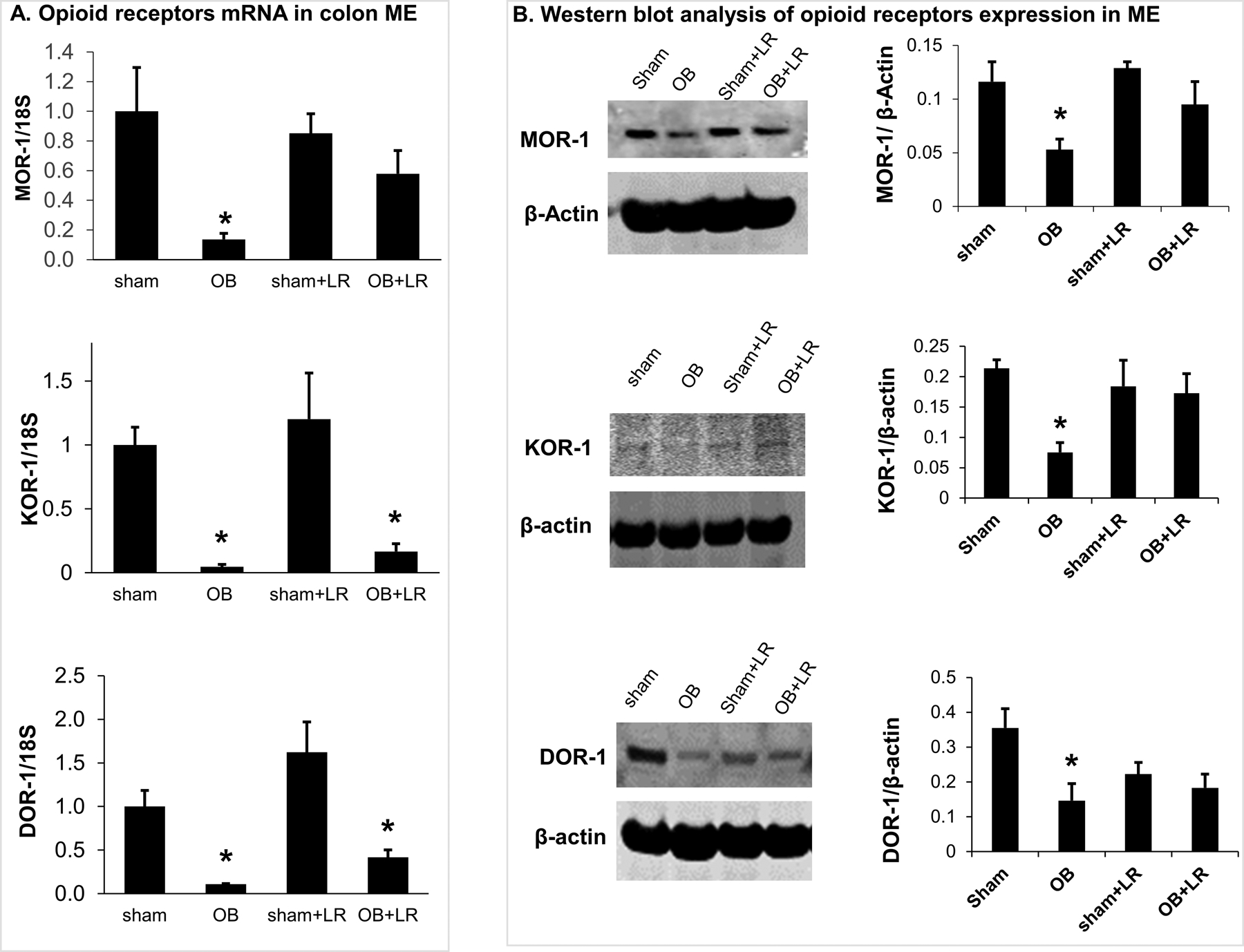

We then focused our study in the colon ME of sham and OB rats to determine the effect of L. reuteri treatment on expression of opioid receptors. Our qRT-PCR results revealed that L. reuteri treatment significantly restored MOR-1 mRNA levels in OB rats [OB+LR: 0.58 (±0.16), p>0.05 Vs sham or sham+LR, Fig 6A]. Treatment with L. reuteri also relatively increased mRNA expression of DOR-1 [OB+LR: 0.41(±0.08); OB: 0.10(±0.007), p>0.05] and KOR-1 [OB+LR: 0.16 (±0.06); OB: 0.04(±0.01), p>0.05], though the differences between groups of OB+LR and sham+LR are still statistically significant (p<0.05) (Fig 6A).

Figure 6: Effect of L. reuteri treatment on expression of opioid receptors in colon muscularis exteranae (ME).

(A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mRNA expression of 3 opioid receptors (MOR-1, KOR-1 and DOR-1) in colon ME samples from sham and OB rat colon. All three opioid receptors mRNA expression is down-regulated significantly in the ME of OB rats. L. reuteri treatment significantly prevented down-regulation of MOR-1 mRNA in OB. N=5 or 6, * p<0.05 vs. sham (Two-way ANOVA). (B) Western blot analysis revealed down-regulation of MOR-1, KOR-1 and DOR-1 protein levels in colon ME of OB rats. L. reuteri treatment improved the expression of all 3 opioid receptors. N=3 or 4, * p≤0.05 vs. sham (Two-way ANOVA).

Western blot analysis of colon ME samples confirmed that MOR-1, KOR-1 and DOR-1 protein expression was all down-regulated in OB compared to sham controls (p<0.05, n=3, Fig 6B). More importantly, when rats were treated with L. reuteri, the MOR, KOR, and DOR expression levels were not different between sham and OB rats (sham+LR and OB+LR, p>0.05) (Fig. 6B).

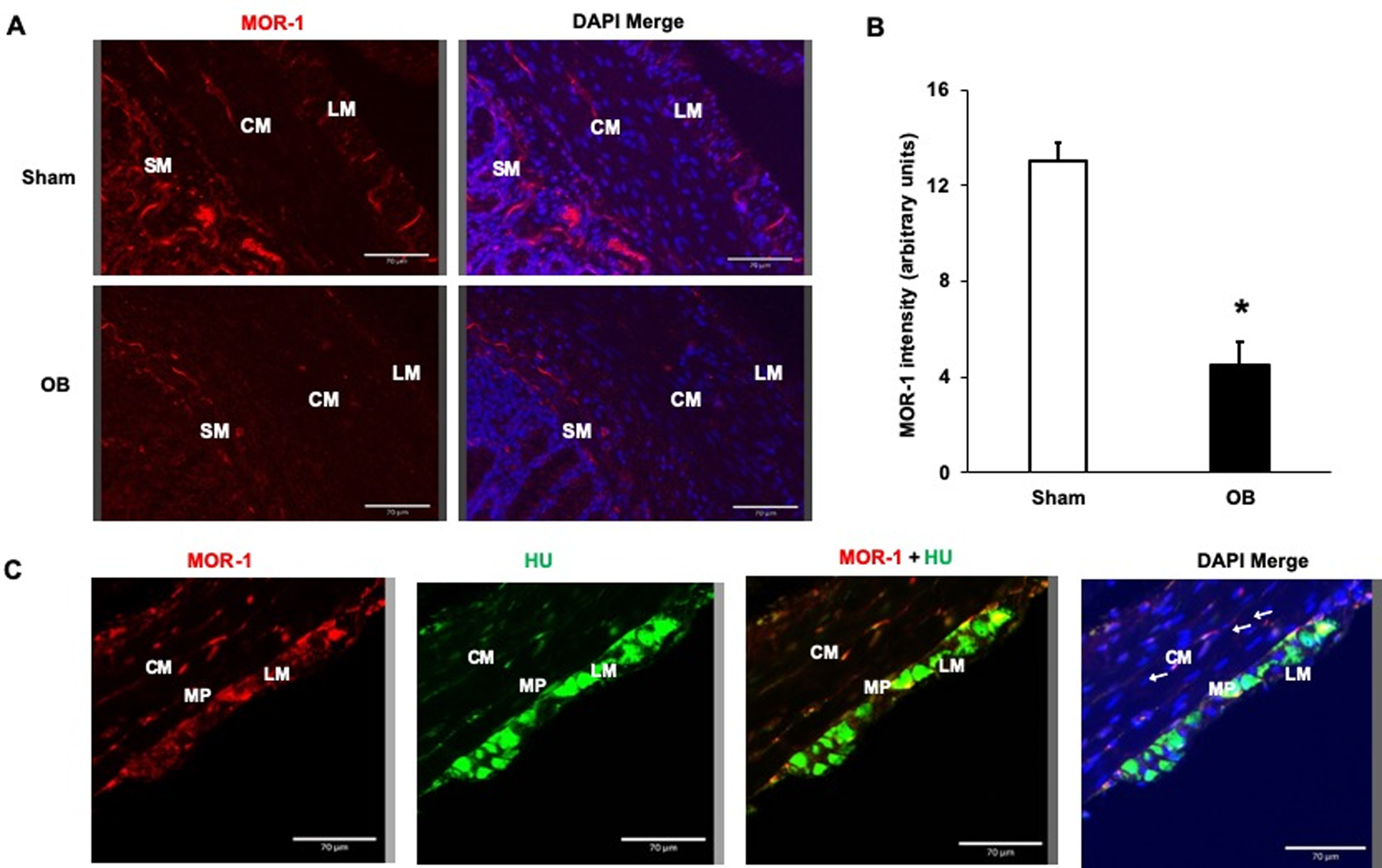

Immunofluorescence staining of MOR-1 in the colon confirmed a significant decrease of MOR-1 expression in colonic ME of OB rats compared to sham control (Fig 7A, 7B). To evaluate the histological localization of MOR-1 in the colon, we performed double immunofluorescence staining to detect MOR-1 and enteric neuronal marker Hu. Our results showed that MOR-1 was expressed not only in the enteric nervous system, but also along the nerve endings detected between smooth muscle cells (Fig 7C).

Figure 7: Immunofluorescence analysis of MOR-1 expression in the colon.

MOR-1 (Red) expression was decreased in the colonic muscularis externae (ME) in OB compared to the sham samples (A). Quantification of MOR-1 fluorescence intensity using ImageJ revealed significant decrease in MOR-1 expression in ME of OB colon compared to Sham (B). * p<0.05 vs. sham (unpaired t-test). Double staining of sham colon sections with MOR-1 (red) and enteric neuronal marker Hu (green) reveals expression of MOR-1 not only in the myenteric plexus neurons, but in nerve endings in the muscularis externae (arrows) (C). Bars 70 μm. LM, longitudinal muscle; CM, circular muscle; SM, submucosa; MP, myenteric plexus.

Peripheral opioid receptor antagonist naloxone methiodide blocks L. reuteri efficacy on referred hyperalgesia

Given that peripheral opioid receptor expression is decreased in the OB colon, and L. reuteri treatment restores expression of opioid receptors, we then determined whether down-regulation of opioid receptors plays a role in hyperalgesia in lumen distention. The withdrawal response to mechanical stimulation to the abdomen in sham and OB rats treated with L. reuteri was evaluated 30 min after administration of peripheral opioid receptor antagonist naloxone methiodide (NLXM, i.p.). Interestingly, NLXM pre-treatment almost completely blocked the analgesic effect of L. reuteri on referred hyperalgesia in OB (Fig 4C). After NLXM treatment, OB+LR rats showed a response of 72.5 (±7.6)%, compared to 31.2 (±9.9)% in sham+LR rats (n=8, p<0.05) (Fig 4C).

Analysis of AUC values showed that the withdrawal responses after naloxone methiodide treatment in LR-treated OB rats (OB+LR+NLXM, AUC = 522±55) were significantly increased compared to either before NLXM treatment (OB+LR, AUC = 316±64) or in sham+LR+NLXM rats (AUC = 252±83, p<0.05, Fig 4D). These results demonstrate a specific role of peripheral opioid receptors in L. reuteri mediated analgesia in lumen distention. Our study did not find any significant change between rats with sham, sham+LR, and sham+LR+NLXM treatment in their withdrawal response to VFF stimulus (Sham: AUC=235±46, Sham+LR: AUC= 220±42, Sham+LR+NLXM: AUC = 252±83) (Fig 4D).

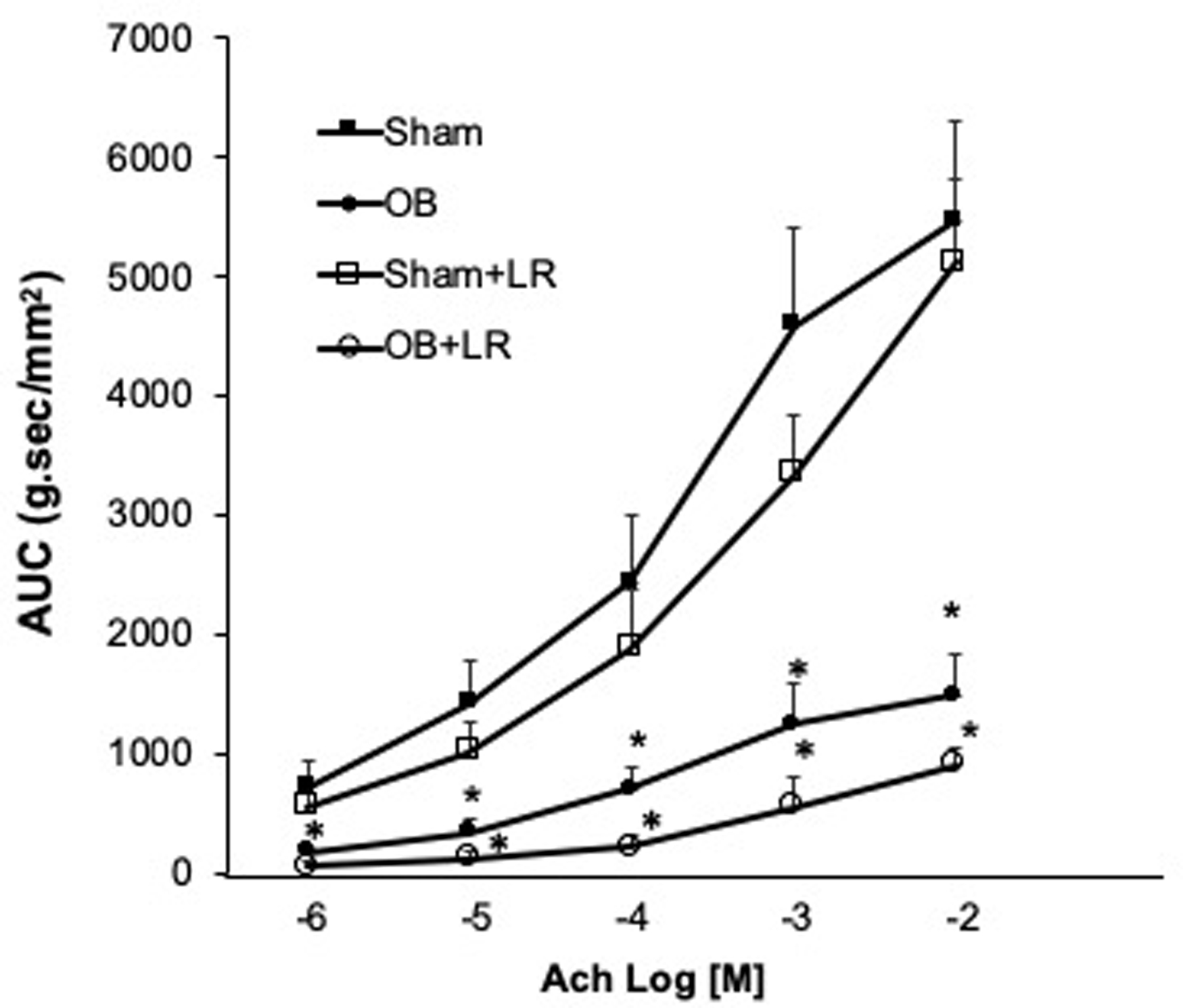

L. reuteri treatment has no effect on the reduced colon muscle contractility in OB rats

Colonic circular muscle contractility was assessed in control and L. reuteri treated sham and OB rats (day 7). Consistent with previous results [43,75], smooth muscle contractility was significantly impaired in obstruction compared to sham in response to ACh challenges (n=8, p<0.05, Fig 8). However, L. reuteri treatment did not improve the impaired muscle contractility in OB rats. We observed still significantly reduced muscle contractility in L. reuteri treated OB rats compared to L. reuteri treated sham (n=8, p<0.05, Fig 8).

Figure 8: Colonic smooth muscle contractility in sham and OB rats with and without L. reuteri treatment.

The colonic circular muscle contractility to ACh was significantly reduced in OB rats compared to sham rats. L. reuteri treatment (LR) did not improve the muscle contractility in the treated OB rats. N=4 or 5, * p<0.05 Vs sham (Two-way ANOVA).

DISCUSSION

Chronic abdominal pain is a main symptom in lumen distention-associated GI diseases, such as OBD and FBD. Clinical and pre-clinical investigations suggest that VHS is a main mechanism underlying abdominal pain in these conditions. Previous studies in partial colon obstruction, a prototype lumen distention model, found that visceral sensitivity is highly augmented in OBD, as the primary sensory neurons projecting to the distended colon demonstrated corresponding hyper-excitability [31,45]. The present work showed that the relative abundance of L. reuteri is markedly reduced in the distended lumen in obstruction. However, precision recolonization with L. reuteri rat strains significantly attenuates sensory neuron hyper-excitability and referred visceral hyperalgesia associated with lumen distention. These data suggest that L. reuteri treatment may have therapeutic potential for abdominal pain in lumen distention-associated conditions. Our results are consistent with previous reports that Lactobacillus are beneficial in the management of OB and abdominal pain in lumen distention associated conditions [11]. Kamiya et al and Ma et al found that L. reuteri ingestion prevented DRG neuron hyper-excitability and visceromotor response to colorectal distention [35,48]. In a double-blind clinical trial, Weizman et al. found that treatment of L. reuteri DSM 17938 in children with functional abdominal pain showed significant decrease in frequency and intensity of abdominal pain [72].

Mechanisms of action of L. reuteri in VHS and abdominal pain were not well understood [51]. However, we discovered that expression of opioid receptors in the peripheral sensory nerve was dramatically down-regulated in the distended colon, and L. reuteri administration largely restored opioid receptor expression in the colon and attenuated DRG neuron hyper-excitability and referred visceral hyperalgesia. Restoration of opioid receptors may account for the improved visceral sensitivity, as pre-treatment with peripheral opioid antagonist blocked the analgesic effect of L. reuteri in lumen distention. Interestingly, two earlier studies reported that L. acidophilus was also able to induce MOR expression in the colon [58,62]. These discoveries that Lactobacillus increases expression of peripheral opioid receptors may constitute a new mechanism underlying the analgesic effects of Lactobacillus.

As specific analgesics to tackle lumen distention-associated abdominal pain are not available, pain in such cases are usually managed with opioid agents. Large doses and chronic use of opioids may be required [27,36,61]. Although morphine and other opioid agents are considered to exert their analgesic effect via central mechanisms, increasing evidence suggests that peripheral opioid receptors may have been implicated in the regulation of visceral hypersensitivity [6,26,33,39,57]. Our findings suggest that peripheral opioid receptors may be involved in the analgesic effects of opioid agents in OBD, as peripheral opioid receptors were down-regulated in chronic lumen distention, and restoration of MOR expression with L. reuteri attenuated visceral hypersensitivity. Furthermore, we found that peripheral opioid antagonist naloxone methiodide effectively blocked the analgesic effect of L. reuteri in the lumen distention model. It is interesting to note that peripheral opioid antagonists are often used to relieve opioid-induced constipation and narcotic bowel syndrome in the management for IBS and OBD [7, 50]. Given our results that peripheral opioid antagonists block the analgesic effect of L. reuteri in lumen distention, we call for careful re-evaluation of using peripheral opioid antagonists in patients with such conditions. In fact, abdominal pain is the most common adverse effect of peripheral opioid antagonists such as naldemedine when it is used to treat opioid-induced constipation [30].

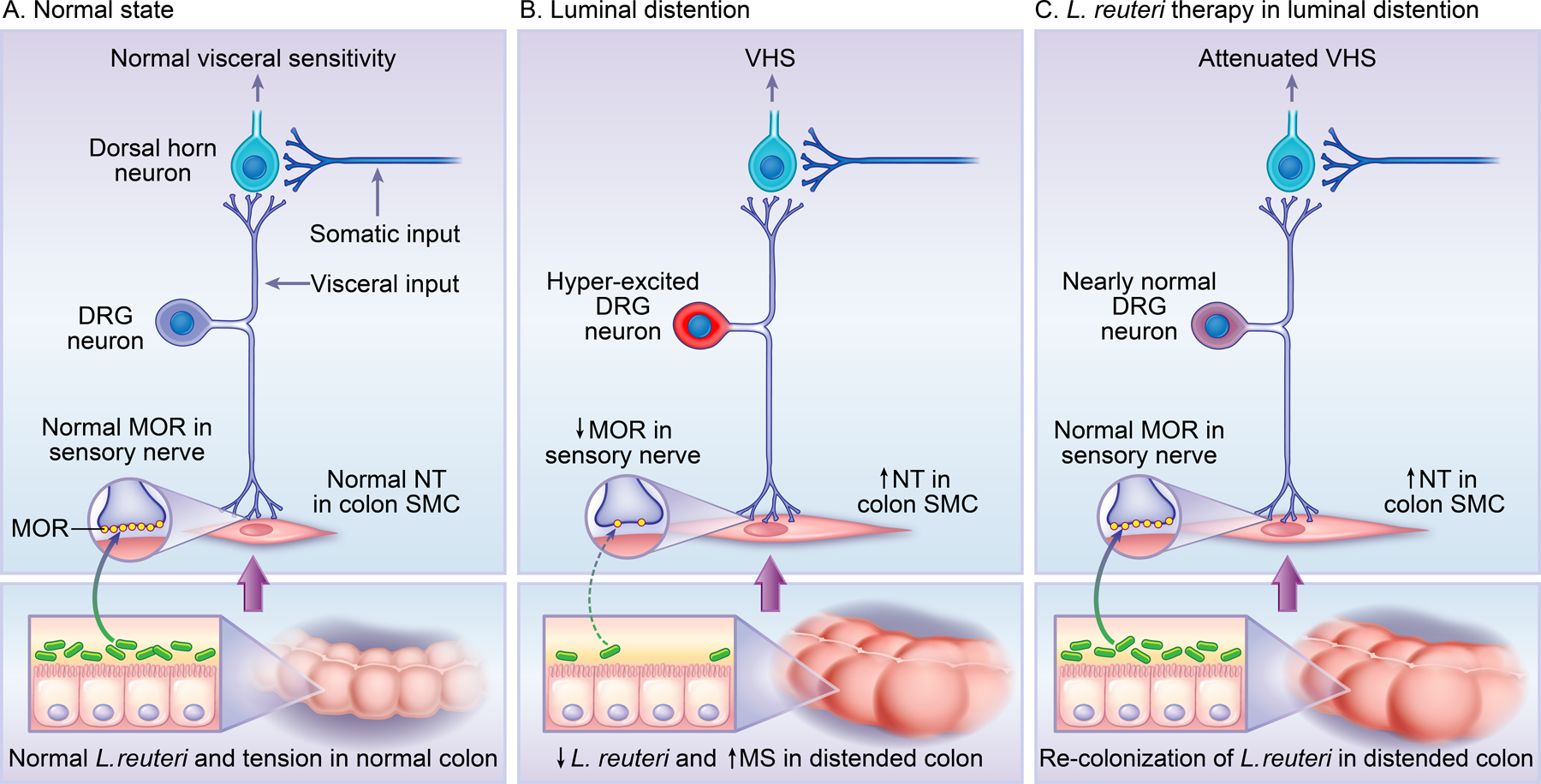

To uncover mechanisms of VHS in lumen distention, we previously discovered that mechanical stress-induced up-regulation of nociceptive mediators NGF and BDNF in gut SMC play an important role in sensitizing primary sensory neurons in OB [21,45]. We now found that down-regulation of peripheral opioid receptors in the primary afferent nerve in the colon (as a part of anti-nociceptive system) may also contribute to VHS in lumen distention in the obstruction model. Treatment with L. reuteri did not significantly affect mechano-transcription of NGF and BDNF, but restored expression of opioid receptors. Together, these studies suggest that both nociceptive and anti-nociceptive systems may help to keep a normal level of visceral sensitivity in the colon. However, mechanical stress in lumen distention-associated conditions could lead to visceral hypersensitivity by peripheral mechanisms involving either up-regulation of nociceptive mediators in gut SMC or down-regulation of the anti-nociceptive system in the sensory nerves (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. Diagram illustrating peripheral mechanisms of visceral hypersensitivity in lumen distention (bowel obstruction) and action of L. reuteri in attenuating visceral hypersensitivity in the colon.

Bowel obstruction increases mechanical stress (MS) and decreases L. reuteri abundance in the colon. These changes lead to upregulation of nociceptive mediators i.e. neurotrophins (NT) NGF and BDNF in colon smooth muscle cells (SMC), and down-regulation of opioid receptors i.e. Mu-opioid receptors (MOR) in the sensory nerve. Up-regulation of NT and down-regulation of MOR contribute to DRG neuron hyper-excitability and visceral hypersensitivity (VHS). Referred visceral hyperalgesia is observed in rats with obstruction by measuring their withdrawal response to mechanical stimulation to the lower abdomen, as the somatic input from that area enters the dorsal horn neurons which also receive visceral input from the colon-projecting DRG neurons. Precision L. reuteri treatment restores L. reuteri abundance in the colon, normalizes expression of MOR (but not NT), and significantly attenuates VHS.

The circumferential mechanical stress in chronic OB appears to affect muscularis externae tissues most effectively, as up-regulation of NGF and BDNF in SMC [21,45] and down-regulation of opioid receptors in sensory nerve occur in the muscularis externae, but not mucosa and submucosa of the distended colon. Bowel obstruction also did not alter expression of nociceptive or anti-nociceptive mediators in the lower abdominal wall where sensation of the colon refers to. The very somatic area (e.g. lower abdomen) is also where we and others [21,31,45] applied von Frey filaments to assess referred visceral hyperalgesia in OB. The absence of altered nociceptive or antinociceptive mediators in the somatic area further suggest that the increased response to mechanical stimulation in the lower abdomen in OB represents referred visceral hyperalgesia (Fig. 9).

Currently, the mechanisms and mediators involved in L. reuteri –induced up-regulation of opioid receptors are not known. However, lactic acid bacteria are known to produce many bio-active metabolites [51,56]. In fact, Lactobacillus are shown to produce opioid peptides, which in turn may act on host opioid receptors to regulate their expression and function [55]. Lactobacillus can also produce GABA, a well-known inhibitory neurotransmitter [51]. Some of the probiotic benefits of L. reuteri have been ascribed to ‘reuterin’, an antimicrobial compound produced by L. reuteri in presence of glycerol. Reuterin is known to inhibit various pathogenic intestinal bacteria [12,13,70]. Our preliminary study on the two L. reuteri rat strains suggests that reuterin production may not be necessary for the anti-nociceptive activity of L. reuteri [Hegde and Shi, unpublished observation]. Growing evidence suggests that microRNAs (miRNAs) are well involved in the regulation of opioid receptor expression and function [4, 34]. Recently, Lactobacillus have been shown to alter miRNA levels in the host gut [22, 60]. It is yet to determine whether miRNAs mediate the effect of L. reuteri on opioid receptor expression in the colon, and if so, what mediators are involved in the process. Nevertheless, our work indicates the capability of gut bacteria in modulating opioid receptor function to potentially alter desensitization, which represents a major treatment concern in the current opioid crisis.

It is of interest that re-colonization of L. reuteri treatment not only attenuated VHS, but also improved food intake and body weight in obstruction. Similar beneficial effects in body weight gain and food intake have been reported in probiotic treatment with other Lactobacillus strains [49]. We do not know what exactly accounted for the improved body weight gain and food intake in our lumen distention model. Neuromuscular dysfunction in obstruction may severely affect appetite, food digestion and absorption [63]. However, quantitative measurement of gut smooth muscle contractility found that L. reuteri treatment did not significantly improve gut motor function in obstruction. It is possible that the improved body weight gain and food intake may be a result secondary to improved visceral sensitivity and attenuated abdominal pain. However, more studies are needed to better understand the mechanism of Lactobacillus species on body weight gain and food intake in lumen distention.

In our initial effort to restore L. reuteri abundance in the distended colon, we first tested human origin strains L. reuteri MM2–3 (PTA-4659) and L. reuteri MM4–1A (PTA-6475). Both of the strains have been used with success in various rodent models [2,17,41,47]. However, in our model of partial colon obstruction, both human strains failed to colonize in the distended bowel. Although exact mechanisms are not known, the highly disturbed microenvironment in the obstructed colon and bacterial host specificity might be responsible for the failed colonization of human origin L. reuteri strains in rats [16]. Interestingly, the L. reuteri strains isolated from rats (L. reuteri 4–1, and L. reuteri 5–1) were able to re-colonize effectively in the obstructed colon (Fig 1), and achieved beneficial effects on visceral sensitivity, food intake and body weight gain. These data indicate that colonization may be a prerequisite for probiotics efficacy in abdominal pain. A precision-based microbial approach is therefore required to advance such therapeutics since major probiotic strain differences are also evident in humans.

In summary, we found that recolonization of L. reuteri in the colon attenuated lumen distention-associated visceral hypersensitivity in a rodent model of partial bowel obstruction. We also found that expression of peripheral opioid receptors, especially MOR-1, in the sensory nerve of the colon was dramatically down-regulated by lumen distention, and that L. reuteri treatment significantly prevented down-regulation of opioid receptors. Moreover, administration of peripheral opioid receptor antagonist naloxone methiodide abolished the analgesic effect of L. reuteri in this model. Taken together, our studies suggest that down-regulation of opioid receptors may partly account for visceral hypersensitivity in GI diseases associated with lumen distention. The analgesic action of L. reuteri may depend on its novel ability to maintain peripheral opioid receptor expression and function in affected tissues (Fig. 9).

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institute of Health (R01 DK102811 to XZS). XZS is also supported in part by R01 DK124611. TS is supported in part by P30 DK56338 and U01 AI24290. The authors thank Ms. Karen S. Prince for her help on figures.

Footnotes

The authors report no competing interests, or other conflict of interest that might be perceived to influence the results or discussion in this paper.

Some of the results in the paper were presented as an abstract in the Digestive Disease Week 2018 in Washington D.C., Jun. 2–5, 2018.

References:

- 1.Agrawal A, Houghton LA, Reilly B, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. Bloating and distension in irritable bowel syndrome: the role of gastrointestinal transit. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104(8):1998–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahl D, Liu H, Schreiber O, Roos S, Phillipson M, Holm L. Lactobacillus reuteri increases mucus thickness and ameliorates dextran sulphate sodium-induced colitis in mice. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2016;217:300–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azpiroz F, Bouin M, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Poitras P, Serra J, Spiller RC. Mechanisms of hypersensitivity in IBS and functional disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2007;19:62–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbierato M, Zusso M, Skaper SD, Giusti P. MicroRNAs: emerging role in the endogenous μ opioid system. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2015;14(2):239–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bielefeldt K Neurochemical and molecular basis of peripheral sensitization In: Chronic abdominal and visceral pain, eds. Pasricha PJ, Willis WD, Gebhart GF. Boka Raton: Informa Healthcare; 2006, 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boue J, Basso L, Cenac N, Blanpied C, Rolli-Derkinderen M, Neunlist M, Vergnolle N, Dietrich G. Endogenous regulation of visceral pain via production of opioids by colitogenic CD4(+) T cells in mice. Gastroenterology 2014;146:166–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camilleri M, Andresen V. Current and novel therapeutic options for irritable bowel syndrome management. Digestive and Liver Disease 2009; 41:854–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cappell MS, Batke M. Mechanical obstruction of the small bowel and colon. Med Clin North Am 2008;92:575–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang L, Lee OY, Naliboff B, Schmulson M, Mayer EA. Sensation of bloating and visible abdominal distension in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96(12):3341–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J, Winston JH, Fu Y, Guptarak J, Jensen KL, Shi XZ, Green TA, Sarna SK. Genesis of anxiety, depression, and ongoing abdominal discomfort in ulcerative colitis-like colon inflammation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2015;308:R18–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen SC, Yen ZS, Lee CC, Liu YP, Chen WJ, Lai HS, Lin FY. Nonsurgical management of partial adhesive small-bowel obstruction with oral therapy: A randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 2005;173:1165–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung TC, Axelsson L, Lindgren SE, Dobrogosz W. In vitro studies on reuterin synthesis by Lactobacillus reuteri. Microb Ecol Health Dis 1989;2:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cleusix V, Lacroix C, Vollenweider S, Duboux M, Le Blay G. Inhibitory activity spectrum of reuterin produced by Lactobacillus reuteri against intestinal bacteria. BMC Microbiol 2007;7:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Giorgio R, Cogliandro RF, Barbara G, Corinaldesi R, Stanghellini V. Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction: Clinical features, diagnosis, and therapy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2011;40:787–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: History, pathophysiology, clinical features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology 2016;150(6):1262–1279.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duar RM, Frese SA, Lin XB, Fernando SC, Burkey TE, Tasseva G, Peterson DA, Blom J, Wenzel CQ, Szymanski CM, Walter J. Experimental evaluation of host adaptation of Lactobacillus reuteri to different vertebrate species. Appl Environ Microbiol 2017;83(12):e00132–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eaton KA, Honkala A, Auchtung TA, Britton RA. Probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri ameliorates disease due to enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli in germfree mice. Infect Immun 2011;79:185–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erben T, Ossig R, Naim HY, Schnekenburger J. What to do with high autofluorescence background in pancreatic tissues - an efficient Sudan black B quenching method for specific immunofluorescence labelling. Histopathology 2016;69:406–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farzaei MH, Bahramsoltani R, Abdollahi M and Rahimi R. The role of visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome: Pharmacological targets and novel treatments. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2016;22(4):558–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, Soffer EE, Spiegel BM, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109(10):1547–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu Y, Lin YM, Winston JH, Radhakrishnan R, Huang LM, Shi XZ. Role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the pathogenesis of distention-associated abdominal pain in bowel obstruction. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018;30(10):e13373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganesh BP, Hall A, Ayyaswamy S, Nelson JW, Fultz R, Major A, Haag A, Esparza M, Lugo M, Venable S, Whary M, Fox JG, Versalovic J. Diacylglycerol kinase synthesized by commensal Lactobacillus reuteri diminishes protein kinase C phosphorylation and histamine-mediated signaling in the mammalian intestinal epithelium. Mucosal Immunol. 2018;11(2):380–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gebhart GF. Pathobiology of visceral pain: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications IV. Visceral afferent contributions to the pathobiology of visceral pain. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2000;278:G834–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gold MS. Overview of pain and sensitization In: Chronic abdominal and visceral pain, Eds. Pasricha PJ, Willis WD, Gebhart GF. Informa Healthcare; 2006, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gore RM , Silvers RI, Thakrar KH, Wenzke DR, Mehta UK, Newmark GM, Berlin JW. Bowel Obstruction. Radiol Clin North Am 2015;53:1225–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenwood-Van Meerveld B, Gardner CJ, Little PJ, Hicks GA, Dehaven-Hudkins DL. Preclinical studies of opioids and opioid antagonists on gastrointestinal function. Neurogastroenterol Motil, Suppl 2, 2004;16:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grunkemeier DM, Cassara JE, Dalton CB, Drossman DA. The narcotic bowel syndrome: clinical features, pathophysiology, and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:1126–39. quiz 1121–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haarman M, Knol J. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of fecal Lactobacillus species in infants receiving a prebiotic infant formula. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006;72:2359–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hegde S, Lin YM, Golovko G, Khanipov K, Cong Y, Savidge T, Fofanov Y, Shi XZ. Microbiota dysbiosis and its pathophysiological significance in bowel obstruction. Sci Rep 2018;8(1):13044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu K, Bridgeman MB. Naldemedine (symproic) for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation. Pharmacy & Therapeutics 2018; 43(10):601–627. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang TY, Hanani M. Morphological and electrophysiological changes in mouse dorsal root ganglia after partial colonic obstruction. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2005;289:G670–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hughes PA, Moretta M, Lim A, Grasby DJ, Bird D, Brierley SM, Liebregts T, Adam B, Blackshaw LA, Holtmann G, Bampton P, Hoffmann P, Andrews JM, Zola H, Krumbiegel D. Immune derived opioidergic inhibition of viscerosensory afferents is decreased in Irritable Bowel Syndrome patients. Brain Behav Immun 2014;42:191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hughes PA, Costello SP, Bryant RV, Andrews JM. Opioidergic effects on enteric and sensory nerves in the lower GI tract: Basic mechanisms and clinical implications. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2016;311:G501–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hwang CK, Wagley Y, Law PY, Wei LN, Loh HH. MicroRNAs in opioid pharmacology. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012;7(4):808–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kamiya T, Wang L, Forsythe P, Goettsche G, Mao Y, Wang Y, Tougas G, Bienenstock J. Inhibitory effects of Lactobacillus reuteri on visceral pain induced by colorectal distension in Sprague-Dawley rats. Gut 2006;55:191–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ketwaroo GA, Cheng V, Lembo A. Opioid-induced bowel dysfunction. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2013;15:344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwon HS, Yang EH, Yeon SW, Kang BH, Kim TY. Rapid identification of probiotic Lactobacillus species by multiplex PCR using species-specific primers based on the region extending from 16S rRNA through 23S rRNA. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2004;239:267–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lembo T, Munakata J, Mertz H, Niazi N, Kodner A, Nikas V, Mayer EA. Evidence for the hypersensitivity of lumbar splanchnic afferents in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 1994;107:1686–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lembo T, Naliboff BD, Matin K, Munakata J, Parker RA, Gracely RH, Mayer EA. Irritable bowel syndrome patients show altered sensitivity to exogenous opioids. Pain 2000;87(2):137–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li F, Lin YM, Sarna SK, Shi XZ. Cellular mechanism of mechanotranscription in colonic smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2012;303: G646–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin YP, Thibodeaux CH, Peña JA, Ferry GD, Versalovic J. Probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri suppress proinflammatory cytokines via c-Jun. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14:1068–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin YM, Li F, Shi XZ. Mechano-transcription of COX-2 is a common response to lumen dilation of the rat gastrointestinal tract. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012;24: 670–7, e295–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin YM, Sarna SK, Shi XZ. Prophylactic and therapeutic benefits of COX-2 inhibitor on motility dysfunction in bowel obstruction: roles of PGE₂ and EP receptors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2012;302:G267–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin YM, Fu Y, Wu CC, Xu GY, Huang LY, Shi XZ. Colon distention induces persistent visceral hypersensitivity by mechanotranscription of pain mediators in colonic smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2015;308: G434–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin YM, Fu Y, Winston J, Radhakrishnan R, Sarna SK, Huang LM, Shi XZ. Pathogenesis of abdominal pain in bowel obstruction: Role of mechanical stress-induced upregulation of nerve growth factor in gut smooth muscle cells. Pain 2017;158(4):583–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin YM, Yu F, Radhakrishnan R, Huang LM, Shi XZ. Stretch-induced BDNF in colon smooth muscle plays a critical role in obstruction associated visceral hypersensitivity by altering Kv function in primary sensory neurons. Gastroenterology 2017;152(5):S203–S204. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu Y, Fatheree NY, Mangalat N, Rhoads JM. Human-derived probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri strains differentially reduce intestinal inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2010;299:G1087–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma XY, Mao K, Wang B, Huizinga JD, Bienenstock J, Kunze W. Lactobacillus reuteri ingestion prevents hyperexcitability of colonic DRG neurons induced by noxious stimuli. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2009;296:G868–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Million M, Angelakis E, Paul M, Armougom F, Leibovici F, Raoult D. Comparative meta-analysis of the effect of Lactobacillus species on weight gain in humans and animals. Microb Pathog 2012;53:100–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moss J, Rosow CE, Development of peripheral opioid antagonists: New insights into opioid effects. Mayo Clin Proc 2008; 83(10):1116–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mu Q, Tavella VJ, Luo XM. Role of Lactobacillus reuteri in human health and diseases. Front. Microbiol 2018; 9:757. doi.org/ 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nunez R, Blesa E, Cabrera R. Hirschsprung’s disease: Clinical features In: Hirschsprung’s disease: Diagnosis and treatment, eds. Nunez R, Lopez-Alonso M New York: Nova Science publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 53.O’Neill SL, Giordano R, Colbert AM, Karr TL, Robertson HM. 16S rRNA phylogenetic analysis of the bacterial endosymbionts associated with cytoplasmic incompatibility in insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992;89:2699–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perez-Burgos A, Wang L, McVey Neufeld KA, Mao YK, Ahmadzai M, Janssen LJ, Stanisz AM, Bienenstock J, Kunze WA. The TRPV1 channel in rodents is a major target for antinociceptive effect of the probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938. J Physiol 2015;593:3943–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pessione E, Cirrincione S. Bioactive molecules released in food by lactic acid bacteria: Encrypted peptides and biogenic amines. Front Microbiol 2016;7:876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Raveschot C, Cudennec B, Coutte F, Flahaut C, Fremont M, Drider D, Dhulster P. Production of bioactive peptides by lactobacillus species: From gene to application. Front Microbiol 2018;9:2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reiss D, Ceredig RA, Secher T, Boué J, Barreau F, Dietrich G, Gavériaux-Ruff C. Mu and delta opioid receptor knockout mice show increased colonic sensitivity. Eur J Pain 2017;21(4):623–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ringel-Kulka T, Goldsmith JR, Carroll IM, Barros SP, Palsson O, Jobin C, Ringel Y. Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM affects colonic mucosal opioid receptor expression in patients with functional abdominal pain - a randomised clinical study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;40:200–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rodríguez EJ. Arqués L, Rodríguez R, Nuñez M, Medina M. Reuterin production by lactobacilli isolated from pig faeces and evaluation of probiotic traits. Lett Appl Microbiol 2003;37:259–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rodríguez-Nogales A, Algieri F, Garrido-Mesa J, Vezza T, Utrilla MP, Chueca N, Garcia F, Olivares M, Rodríguez-Cabezas ME, Gálvez J. Differential intestinal anti-inflammatory effects of Lactobacillus fermentum and Lactobacillus salivarius in DSS mouse colitis: impact on microRNAs expression and microbiota composition. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017; 61(11). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roeland E, von Gunten CF. Current concepts in malignant bowel obstruction management. Curr Oncol Rep 2009;11:298–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rousseaux C, Thuru X, Gelot A, Barnich N, Neut C, Dubuquoy L, Dubuquoy C, Merour E, Geboes K, Chamaillard M, Ouwehand A, Leyer G, Carcano D, Colombel JF, Ardid D, Desreumaux P. Lactobacillus acidophilus modulates intestinal pain and induces opioid and cannabinoid receptors. Nat Med 2007;13:35–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sarna SK and Shi XZ. Function and regulation of colonic contractions in health and disease In:Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract, ed. Johnson LR. Vol 1, Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press; 2006, 965–993. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Savino F, Garro M, Montanari P, Galliano I, Bergallo M. Crying time and RORγ/FOXP3 expression in Lactobacillus reuteri DSM17938-treated infants with colic: A randomized trial. J Pediatr 2018;192:171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Serra J, Azpiroz F, Malagelada JR. Impaired transit and tolerance of intestinal gas in the irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2001;48(1):14–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shi XZ, Lin YM, Powell DW, Sarna SK. Pathophysiology of motility dysfunction in bowel obstruction: role of stretch-induced COX-2. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2011;300:G99–G108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shi XZ, Sarna SK. Cell culture retains contractile phenotype but epigenetically modulates cell-signaling proteins of excitation-contraction coupling in colon smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2013;304:G337–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shi XZ. Mechanical regulation of gene expression in gut smooth muscle cells. Front Physiol 2017;8:1000. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.01000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shi XZ, Lin YM, Hegde S. Novel insights into the mechanisms of abdominal pain in obstructive bowel disorders. Front Integr Neurosci 2018;12:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Spinler JK, Taweechotipatr M, Rognerud CL, Ou CN, Tumwasorn S, Versalovic J. Human-derived probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri demonstrate antimicrobial activities targeting diverse enteric bacterial pathogens. Anaerobe 2008;14:166–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wegh CAM, Benninga MA, Tabbers MM. Effectiveness of probiotics in children with functional abdominal pain disorders and functional constipation: A systematic review. J Clin Gastroenterol 2018;52:S10–S26. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weizman Z, Abu-Abed J, Binsztok M. Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 for the management of functional abdominal pain in childhood: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Pediatr 2016;174:160–164.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Whitehead WE, Holtkotter B, Enck P, Hoelzl R, Holmes KD, Anthony J, Shabsin HS, Schuster MM. Tolerance for recto-sigmoid distension in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 1990;98:1187–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Winston J, Toma H, Shenoy M, Pasricha PJ. Nerve growth factor regulates VR-1 mRNA levels in cultures of adult dorsal root ganglion neurons. Pain 2001;89:181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wu CC, Lin YM, Gao J, Winston JH, Cheng LK, Shi XZ. Are interstitial cells of Cajal involved in mechanical stress-induced gene expression and impairment of smooth muscle contractility in bowel obstruction? PLoS One 2013;8:e76222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]