Abstract

Verification of relationship status beyond self-report is an important aspect in sexually transmitted infection research, including partner treatment studies where primary sexual partners are targeted for enrollment. This exploratory study describes the use of a novel couples’ verification tool in a male partner treatment study of women with bacterial vaginosis.

Keywords: couples verification tool, sexually transmitted infection, partner treatment study

SHORT SUMMARY

This study describes the use of a novel couples’ verification tool in a male partner treatment study of women with bacterial vaginosis.

BACKGROUND

Verification of relationship status beyond self-report is an important aspect in research involving groups of related individuals, including HIV/sexually transmitted infection (STI) research where primary sexual partners are targeted for enrollment (1). Important reasons to verify relationship status beyond self-report are to avoid potential deceptive practices by participants regarding study eligibility (which can be quite common in settings where reimbursement is provided) as well as protect the integrity of the data (2, 3). Utilizing a couples’ verification tool in HIV/STI partner studies may be a useful addition beyond self-report to prevent enrollment of couples who are not primary sexual partners, which may confound study results. In addition to the tool alerting study staff of a potential violation of eligibility criteria, informing potential participants of objective verification measures has been shown to promote truthful reporting in other types of clinical research, such as the use of biochemical measures to minimize under-reporting of smoking (4).

Despite these potential advantages, many prior couples-based HIV/STI research studies have relied solely on self-report of relationship status (5–9), although couples’ verification tools have been occasionally used in some studies (10), including studies of HIV risk among urban, street-based drug-using couples (1). With this in mind, the objective of this study was to describe our use of a novel couples’ verification tool in a multi-center male partner treatment study of women with recurrent bacterial vaginosis (BV) (NCT02209519).

METHODS

The parent trial was conducted at outpatient clinics at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) in Birmingham, AL and Wayne State University in Detroit, MI. The UAB and Wayne State University Institutional Review Boards approved this study (protocols #’s: IRB-130627009 and IRB-130912027, respectively), including use of the couples’ verification tool, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Women were eligible for the trial if they were ≥18 years of age, heterosexual with a regular male partner, reported ≥2 episodes of BV during the past year, had current BV symptoms, were diagnosed with BV based on Amsel (11) and/or Nugent (12) criteria, and were willing to abstain from sex or use condoms during the study. Exclusion criteria included HIV, pregnancy or breastfeeding, trichomoniasis, allergy to 5-nitroimidazoles, and concurrent use of lithium, coumadin, dilantin, or antabuse. Women were asked to refer their regular male sexual partner within 72 hours for potential enrollment; partners had to be ≥18 years and willing to abstain from sex or use condoms during the study. If the couple was eligible, the male partner was randomized to a 7 days of oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily versus placebo. Participant reimbursement was $50/visit at UAB and $60/visit at Wayne State University (4 visits took place for women and 2 for men at each site). The primary outcome measure was the BV recurrence rate based on Amsel and/or Nugent score in the female partner at 16 weeks.

Verification of couple status was based on self-report for the purposes of the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the trial. Couples were not required to be legally married, thus legal documentation such as a marriage license was not used to verify couple status. We used this opportunity to explore the use of our novel couples’ verification tool in this setting (Table 1). This tool was adapted from a previous couples’ verification tool used in a study of HIV risk among 353 urban, street-based drug-using couples (1). Our tool separately asked each female and male partner a rotating series of 6 parallel questions of an intimate or personal nature about aspects of their relationship to “test” if the couple was legitimate as a regular couple (10). The 6 questions were randomly drawn from a pool of 20 questions, and 13 versions of the tool were designed. A couple was defined as having perfect agreement on the tool if they answered all 6 questions correctly. If they answered 2-5 questions correctly, they were defined as having partial agreement. For the purposes of this study, if the couple answered at least 4 out of 6 questions correctly, their relationship status was considered verified beyond self-report (it should be noted, however, that some prior studies using a couples’ verification tool did not implement a hard-and-fast-rule for passing it) (1). Our tool was individually administered to all female and male partners in the trial with pencil and paper in the privacy of an exam room at each of the study sites. As this was an exploratory study using a novel verification tool, couples were not excluded from the trial due to low scores on the tool. All data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet by author KH for analysis.

Table 1.

Couples’ Verification Tool Questions*

| Question | Female Questions | Male Questions |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | When did you and your partner last have vaginal sex? | When did you and your partner last have vaginal sex? |

| 2 | Please tell me your birthday. When is your partner’s birthday? | When is your partner’s birthday? Please tell me your birthday. |

| 3 | Last time you had sex did your partner use a condom? | Did you use a condom last time you had sex? |

| 4 | How many tattoos do you have? How many tattoos does your partner have? | How many tattoos does your partner have? How many tattoos do you have? |

| 5 | How old are you? How old is your partner? | How old is your partner? How old are you? |

| 6 | Where did you meet your partner? | Where did you meet your partner? |

| 7 | Do you have a car? Does your partner have a car? | Does your partner have a car? Do you have a car? |

| 8 | What is your favorite place to get food from? What is your partner’s favorite place to get food from? | What is your partner’s favorite place to get food from? What is your favorite place to get food from? |

| 9 | What is your cell phone number? What is your partner’s cell phone number? | What is your partner’s cell phone number? What is your cell phone number? |

| 10 | Do you have any kids? Does your partner have any kids? | Does your partner have any kids? Do you have any kids? |

| 11 | When you sleep together, which side of the bed do you sleep on? Your partner? | When you sleep together, which side of the bed does your partner sleep on? You? |

| 12 | How do you prevent pregnancy? | How does your partner prevent pregnancy? |

| 13 | What is your favorite drink? What is your partner’s favorite drink? | What is your partner’s favorite drink? What is your favorite drink? |

| 14 | Where do you spend time together? | Where do you spend time together? |

| 15 | Where do you work? Where does your partner work? | Where does your partner work? Where do you work? |

| 16 | Is your mom alive? Is your partner’s mom alive? | Is your partner’s mom alive? Is your mom alive? |

| 17 | What kind of underwear do you wear? What kind of underwear does your partner wear? | What kind of underwear does your partner wear? What kind of underwear do you wear? |

| 18 | What high school or college did you go to? What high school or college did your partner go to? | What high school or college did you go to? What high school or college did your partner go to? |

| 19 | Is your partner circumcised? | Are you circumcised? |

| 20 | How many siblings do you have? How many siblings does your partner have? | How many siblings does your partner have? How many siblings do you have? |

Six questions were selected from this list for multiple questionnaire versions.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for participant demographics and STI history according to gender and study site. Couple agreement was investigated by comparing the percentage of couples with perfect agreement according to groups defined by age (<30, >30 years) and education (high school degree or less, some college or more) using chi-square tests; mean age was also compared according to agreement group using two-sample t-tests. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Between February 2015–March 2019, 222 women and 214 men were screened for the trial; 214 “regular” heterosexual couples were subsequently enrolled. Couples’ verification data were available for 201/214 (93.9%) of couples. Of these 201 couples, 5 were missing questionnaire version on their data collection forms; thus, data are presented for 196 couples (122 from UAB (62%), 74 (38%) from Wayne State). Supplementary Table 1 summarizes socio-demographic and STI history data for this population, stratified by site. Mean ages of the women and men were 32.1 years (±7.5) and 34.3 years (±9.6), respectively. A large majority were African American (158/196 [81%] of women, 164/196 [84%] of men). The sites differed significantly in terms of age and race for both sexes as well as level of education for men; UAB participants were slightly younger with more African Americans compared to Wayne State. In addition, a larger percentage of men at Wayne State were in the higher education category compared to men at UAB. The sites did not differ significantly with regards to STI history.

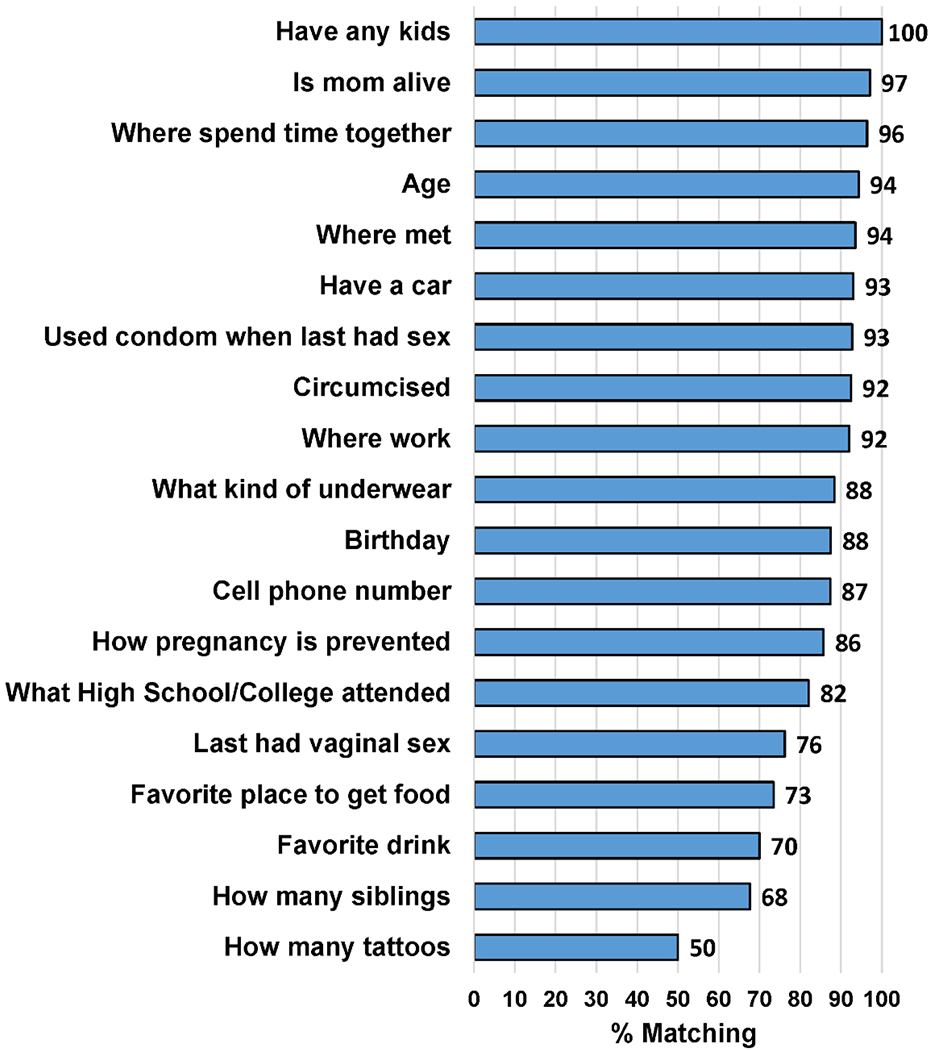

Figure 1 shows the percentage of correct couples’ responses per question across both sites. As there were 13 versions of the tool (each including 6 questions), not all questions were answered by all couples; the sample size for each of the questions ranged from 10-111. The distribution of questions asked was not significantly different between sites (p=0.404). Of the 196 couples, a large percentage (183; 93.4% [95% CI, 88.9%-96.4%]) answered 4 or more questions correctly (4 questions: 22 [11.2%]; 5 questions: 67 [34.2%]; 6 questions: 94 [48.0%]). Only 13 couples, 4/196 [2.0%] and 9/196 [4.6%], respectively, answered 2 or 3 questions correctly. The question with the highest percentage of correct responses (100%) was regarding how many children each partner had. In contrast, the question with the lowest percentage (50%) of correct responses asked how many tattoos each partner had. Questions related to whether or not the partners’ mom was alive, where the couple likes to spend time together, the partners’ age, where they met, whether they used a condom at last vaginal sex, where they work, and if the male was circumcised had a high percentage of correct responses, ranging from 92-97%. In contrast, questions related to the number of siblings, favorite drink, favorite place to get food, and date of last vaginal sex had a lower percentage of correct responses, ranging from 68%-76%. Interestingly, the percentage of perfect agreement responses significantly differed by site: 72/122 (59.0%) of UAB couples had perfect scores compared to only 22/74 (29.7%) of Wayne State couples (p<0.001). Couples’ agreement responses did not significantly differ according to age, race, or level of education across sites (Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 1:

Percentage of Couples with Matching Responses on Items from the Couples’ Verification Tool

DISCUSSION

This study is unique in that it is one of few HIV/STI research studies to incorporate the use of a couples’ verification tool in a partner treatment trial. A prior HIV risk study of 353 urban, street-based, drug-using couples using a couples’ verification tool found it to be invaluable in preventing enrollment of couples who were not primary sexual partners (1). With regards to BV, all six prior male partner treatment trials only used self-report to verify couple status (13–18). In our study, a large percentage (93.4%) of self-reported “regular” couples answered at least 4 out of 6 questions on the tool correctly, with almost half (48%) answering all questions correctly. This is reassuring that the large majority of participants in the trial knew each other intimately; only 13 couples would have been excluded if this tool was formally used as an exclusion criteria.

It is interesting to note that questions with the least amount of correct responses asked participants for numerical answers (i.e. number of each partners’ tattoos and siblings; questions said to be a good indicator of couple status in prior studies) (1). It is possible that partially matching responses (i.e. a female stating her male partner had 8 tattoos while he reported 9) may not have been counted as correct in these instances. In addition, questions with elements of dates (i.e. date of last vaginal sex) also had a lower number of correct responses. Future versions of this tool used in partner treatment studies should consider limiting these types of questions to one or two per questionnaire and specifying an a priori defined range for determining matching responses, as well as focusing on using more concrete questions (i.e. “is your partners’ mom alive?”).

The primary limitation of this study is that we have not yet formally validated this couples’ verification tool which would require demonstrating that the tool’s responses differ for non-couples as compared to couples; this should be the next step in this line of research. Validation across a range of relationships including new or casual sexual partnerships versus regular/long-term partnerships should also be performed. Another limitation is the potential subjective nature of several of our questions (i.e. the kind of underwear a partner wears).

We found no demographic differences in couple agreement on the tool, suggesting that demographic groups would not be differentially excluded if responses on the tool were used as a study inclusion criteria (which could be proposed once the tool is validated). Currently, use of a tool such as the one described here appears to be helpful in providing quantitative data to assist in accurately discerning regular sexual partnerships beyond self-report, as well as potentially encouraging truthful reporting.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Joy Lewis and Sanquetta McClendon for their assistance recruiting and enrolling couples in this study. This study was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) (grant U01AI108509 awarded to Jane R. Schwebke, MD). Christina A. Muzny, MD, MSPH is currently funded by NIAID (R01AI146065-01A1).

REFERENCES

- 1.McMahon JM, Tortu S, Torres L, et al. Recruitment of heterosexual couples in public health research: a study protocol. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernandez Lynch H, Joffe S, et al. Association Between Financial Incentives and Participant Deception About Study Eligibility. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2(1):e187355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee CP, Holmes T, Neri E, Kushida CA. Deception in clinical trials and its impact on recruitment and adherence of study participants. Contemp Clin Trials 2018;72:146–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray DM, O’Connell CM, Schmid LA, Perry CL. The validity of smoking self-reports by adolescents: a reexamination of the bogus pipeline procedure. Addict Behav 1987;12(1):7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NIMH Multisite HIV/STD Prevention Trial for African American Couples Group. Methodological overview of an African American couple-based HIV/STD prevention trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;49 Suppl 1:S3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witte SS, El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, et al. Recruitment of minority women and their main sexual partners in an HIV/STI prevention trial. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2004;13(10):1137–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Wu E, et al. Couple-based HIV prevention for low-income drug users from New York City: a randomized controlled trial to reduce dual risks. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011;58(2):198–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Bassel N, Witte SS, Gilbert L, et al. Long-term effects of an HIV/STI sexual risk reduction intervention for heterosexual couples. AIDS Behav 2005;9(1):1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pappas-DeLuca KA, Kraft JM, Edwards SL, et al. Recruiting and retaining couples for an HIV prevention intervention: lessons learned from the PARTNERS project. Health Educ Res 2006;21(5):611–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Syvertsen JL, Robertson AM, Abramovitz D, et al. Study protocol for the recruitment of female sex workers and their non-commercial partners into couple-based HIV research. BMC Public Health 2012;12:136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, et al. Nonspecific vaginitis. Diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med 1983;74(1):14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol 1991;29(2):297–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swedberg J, Steiner JF, Deiss F, et al. Comparison of single-dose vs one-week course of metronidazole for symptomatic bacterial vaginosis. JAMA 1985;254(8):1046–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mengel MB, Berg AO, Weaver CH, et al. The effectiveness of single-dose metronidazole therapy for patients and their partners with bacterial vaginosis. J Fam Pract 1989;28(2):163–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moi H, Erkkola R, Jerve F, et al. Should male consorts of women with bacterial vaginosis be treated? Genitourin Med 1989;65(4):263–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vejtorp M, Bollerup AC, Vejtorp L, et al. Bacterial vaginosis: a double-blind randomized trial of the effect of treatment of the sexual partner. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1988;95(9):920–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vutyavanich T, Pongsuthirak P, Vannareumol P, et al. A randomized double-blind trial of tinidazole treatment of the sexual partners of females with bacterial vaginosis. Obstet Gynecol 1993;82(4 Pt 1):550–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colli E, Landoni M, Parazzini F. Treatment of male partners and recurrence of bacterial vaginosis: a randomised trial. Genitourin Med 1997;73(4):267–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.