Abstract

Although visual acuity is largely stable in adults with coloboma, they are at risk of being labelled as glaucoma suspects and developing early-onset cataracts. Broad systemic screening may identify previously unnoticed comorbidities.

Coloboma is a rare, potentially blinding disorder caused by failure of optic fissure closure;1 it may be isolated or paired with systemic abnormalities (i.e., syndromic). While associations and comorbidities of coloboma in children are broadly recognized, these are less well-characterized in adults.2

We queried the electronic medical records of the National Eye Institute (NEI, Bethesda, MD, USA) for coloboma patients >18 years of age at their last visit. Patients were consented to an NEI- sponsored, IRB approved, clinical research protocol for studying the genetics and natural history of coloboma. Demographic, ophthalmologic, medical and family history were reviewed for each patient.

Patients with atypical isolated optic nerve coloboma were excluded if it was unclear that they manifested a true failure of optic fissure closure. Sixteen patients with clearly syndromic coloboma were excluded given that they are characterized elsewhere in the literature. Sixty-two patients (104 eyes) with apparently isolated coloboma integrated our cohort. An “isolated” coloboma patient was defined by not having any systemic abnormalities readily discernible on physical exam. Twenty-seven (44%) of these patients were included in a previous report.3

The mean age of the cohort at their last visit was 37 ± 14 years old (standard deviation). Most of our patients (68%) presented with bilateral coloboma and 56% of the eyes had both anterior and posterior segment involvement. The characteristics regarding the extension of the coloboma are described in Table S1 (available at www.aaojournal.org).

Visual acuity was stable and that there were no other signs of a progressive disease over the follow up visits (mean follow up time of 7.1 ± 4.4 years). Forty-seven patients (76%) had at least one eye with visual acuity >20/60. Nine patients (15%) were visually impaired (<20/60 to >20/200), and six (10%) were legally blind (≤20/200 in the better eye). Visual acuity of the eye with coloboma ranged from 20/20 to no light perception (NLP). Fifty of the 104 colobomatous eyes (48%) had 20/40 vision or better, 23% were 20/400 or worse.

Most of the patients had myopia (n=34; 55%), followed by no refractive error (n=21, 34%) and hyperopia (n=7, 11%). High and moderate myopia (refraction greater than −3.00 D and/or axial length greater than 24.7 mm) were present in at least one eye on 16 patients (26%). Six myopes had axial lengths <23.5 mm and normal keratometry (median K1/K2: 43.38 D/42.8 D), implying that myopia may be due to abnormally developed corneas (affecting the stroma or the posterior corneal surface) and/or a lens component.

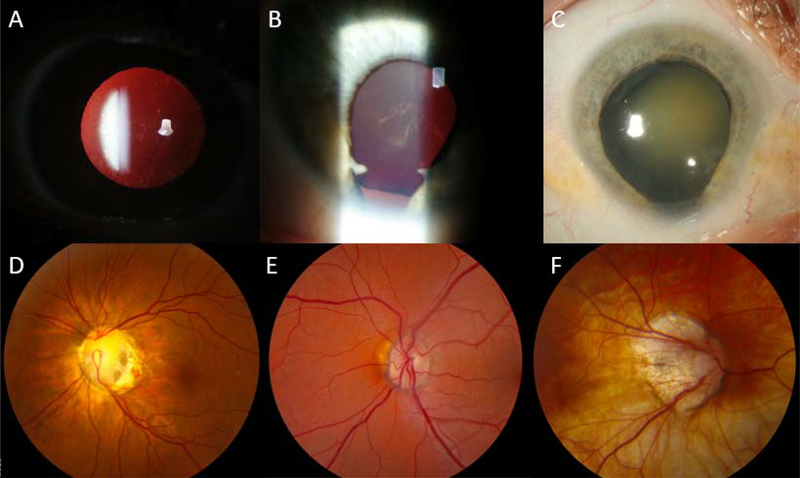

The most frequent ocular anomalies in pediatric populations with coloboma are strabismus and cataracts, the latter affecting up to 16% of the patients.3 We found the same pattern in our adult cohort, in which strabismus or a history of it was present in 37% of the patients and cataracts in 50% (31 patients, Figure A–C). Twenty-five out of the 31 patients with cataracts had anterior segment coloboma. While the precise reason for this higher cataracts’ prevalence is unclear, we postulate that abnormal development of the eye may affect lens cells’ physiology such that they are less able to retain soluble cytoplasmic proteins, ergo lens clarity. Cataract extraction in these patients may be needed at a younger age than in general population and should be approached with extra caution due to possibly associated lens coloboma and phacodonesis.

Figure :

Types of lens opacities and dysplastic optic nerves in adult patients with coloboma. Cataracts range from non-visually significant nuclear dots (A), sutural (B) and/or cortical cataracts all the way to visually significant, mature nuclear (C) cataract. Dysplastic optic nerves are often present in patients with posterior segment coloboma. Note that these include splitting of the superior and inferior vascular trunks with an inferior slope to the optic nerve cup (D); optic nerve hypoplasia with an inferior crescent of scleral show (E); and highly tilted, myopic discs with peripapillary atrophy (F).

Thirteen patients (13/62; 21%) had a pachymetry of more than 600 μm in at least one eye (normal central corneal thickness: 549.34 ± 29.14 pm), six of which had microcornea.4 The mean endothelial cell density was within normal limits (2645 cell/mm ) and there was no evidence of endothelial dropout. The intraocular pressure (IOP) was borderline-high (18–22 mmHg) in six of these patients. This feature combined with hypoplastic or dysplastic optic nerves (present in 81% of our patients, Figure D–F), put patients with coloboma at risk of being labelled as glaucoma suspects (n= 7, 11%) and overtreated with ocular hypotensive drops (n=5, 8%). Karatepe et al reported on isolated iris coloboma patients with thicker corneas although normal IOP.5

Five of our patients had retinal detachment (8%), all with coexisting ocular conditions (e.g, high myopia) or history of trauma. Three of these patients were not treated (due to poor visual prognosis) while the remaining two had their retina successfully reattached. This lower prevalence compared to other reports in the literature (up to 40%)6 could be due to referral bias (i.e., participating in a research study vs. clinical treatment in a retina practice) and/or the relatively low prevalence of other ocular comorbidities such as microphthalmia (8/62; 13%). Other less frequent complications in the posterior segment were choroidal neovascularization (2/62; 3%), vitreous hemorrhages and subretinal fluid.

Systemic health was evaluated in every participant by a standard systemic workup similar to the one used in children with syndromic forms of coloboma, including: physical exam, audiology, kidney ultrasound, blood chemistries & urinalysis, and spine x-ray. Additional exams were added as clinically indicated. Forty-six patients had systemic issues (74%), while systemic abnormalities in pediatric cohorts have been found in up to 38% of the evaluated patients.7 Thirty-nine patients (63%) had at least one systemic finding characteristic of syndromic coloboma (musculoskeletal, renal, cardiac, audiologic or neuro/psychological), while seven (11%) had an issue not likely associated with a genetic syndrome (i.e., hypothyroidism, hypercholesterolemia, prostate cancer). Although this high prevalence is to be expected along with the aging of our cohort, this is certainly higher than in general adult populations (health issues reported by up to 26.9% in 2017 National Health Interview Survey). Overall, there was no significant deterioration in health over the time of the study. All patients were living an independent life, working or studying, including those with poor visual acuity.

This study provides the first extensive data on the visual and systemic prognosis for adult patients with ocular coloboma. We note that visual acuity is largely stable, retinal complications may not be as high as previously reported, cataract may appear at a comparatively early age, some may be overtreated for glaucoma, and that broad systemic screening may identify other important comorbidities.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: Location and extension of uveal coloboma among our cohort.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was supported by the Intramural Program of the National Eye Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No authors have a conflict of interest bearing on the contents of this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1).Chang L, Blain D, Bertuzzi S, Brooks BP. Uveal coloboma: clinical and basic science update. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17(5):447–470. doi: 10.1097/01.icu.0000243020.82380.f6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Uhumwangho OM, Jalali S. Chorioretinal coloboma in a paediatric population. Eye (Lond). 2014;28(6):728–733. doi: 10.1038/eye.2014.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Huynh N, Blain D, Glaser T, et al. Systemic diagnostic testing in patients with apparently isolated uveal coloboma.Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156(6):1159–1168.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.06.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Gharieb HM, Ashour DM, Saleh MI, Othman IS. Measurement of central corneal thickness using Orbscan 3, Pentacam HR and ultrasound pachymetry in normal eyes [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 27]. Int Ophthalmol. 2020; 10.1007/s10792-020-01344-1. doi: 10.1007/s10792-020-01344-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Karatepe HaşhaşAS Arifoğlu HB, Yuce Y, Duru N, Ulusoy DM, Zararsiz G. Evaluations of Corneas in Eyes with Isolated Iris Coloboma. Curr Eye Res.2017;42(1):41–46. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2016.1151054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Jesberg DO, Schepens CL. Retinal detachment associated with coloboma of the choroid. Arch Ophthalmol. 1961;65:163–173. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1961.01840020165003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Skalicky SE, White AJR, Grigg JR et al. ; Microphthalmia, Anophthalmia, and Coloboma and Associated Ocular and Systemic Features. Understanding the Spectrum . JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(12):1517–1524. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.5305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: Location and extension of uveal coloboma among our cohort.