Abstract

Patient-centered care requires providing care that is responsive to patient preferences, needs, and values, yet data on parent and youth treatment preferences remains sparse. The present study 1) identifies variations in parent and youth preferences for depression treatment, and 2) explores relationships between parent and youth demographics and psychosocial functioning, and the preferences that parents and youth endorse. Participants were 64 youth and 63 parents awaiting randomization in a clinical trial evaluating psychosocial youth depression treatments. Parents preferred treatments that emphasize learning skills and strategies (82.5%) and include the parent in treatment at least some of the time (96.8%). Youth preferred that the therapist meet mostly with the youth alone (67.2%) but share at least some information with parents (78.1%). Youth (43.8%) tended to respond “don’t know” to questions about their preferred therapeutic approach. Understanding parent and youth preferences, especially psychosocial treatment preferences, is needed to provide high-quality, patient-centered care.

Keywords: child, parent, depression, preference, treatment

The value of patient-centered care has been increasingly recognized as a key quality improvement target in health and behavioral health care delivery [1]. Patient-centered care requires “Providing care that is respectful of, and responsive to, individual patient preferences, needs and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions” [2]. Despite the importance of understanding what patients – both youth and their parents – value and prefer, and the potential impact parent and youth preferences may have on treatment engagement [3, 4], we have very little infonnation on youth and parent preferences for behavioral health treatment, especially preferences regarding psychosocial treatment approaches for younger youth. As youth with severe impairment receive alarmingly low rates of behavioral health care [5], improving the fit between patient values and preferences and available treatments may lead to improved rates of care and patient outcomes.

Youth depression is an especially important area to study in relation to patient values and preferences. Depression frequently begins in childhood and is estimated to affect roughly 350 million people worldwide [6] and has been identified as the leading cause of disability as indexed by Years Lived with Disability [7]. Both psychosocial and medication treatments have demonstrated efficacy for treating depression in adolescents and to a lesser extent children [8–10], and multiple psychosocial approaches have demonstrated at least moderate empirical support in the treatment of youth depression, including skills-based approaches such as cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy [8, 11]. In addition to skills-based approaches, many clinicians focus their psychotherapy practice on providing support, identifying themselves as client-centered practitioners [12]. In addition, established treatment approaches for youth depression, and clinicians’ self-reported practice, varies on the degree to which parents are involved in youth-focused treatments [8]. Thus, the empirical evidence and clinicians’ current practice include a wide range of treatment choices in terms of, at minimum, treatment approach and treatment participants (i.e., parent-, youth-, or family-focused).

Even though parent and youth preferences should be key factors in choosing among treatment options for youth depression, there is little information available about what parents and youth actually want in depression treatment, especially in relation to factors that vary across types of psychosocial treatments (e.g., what kind of treatment to provide, who participates in treatment). The limited research on depression treatment preferences focuses on medication versus psychosocial treatment. In this comparison, parents and youth tend to have preferences regarding the type of treatment they want, and this can impact the treatments they seek as well as response to treatment. For instance, adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms tend to prefer psychosocial treatment rather than medications, although adolescents with longer treatment histories and more clear depressive disorders (compared to those with high symptom levels that do not meet depressive disorder criteria) tend to be more likely to prefer medication treatment [13]. Adolescents also may be more likely to prefer counseling over medication if they reported fewer negative attitudes toward depression treatment, more negative attitudes towards medications, and fewer anxiety symptoms. Preferences for non-pharmacological approaches were also found in community-based samples of adolescents [14]. Caporino and Karver [15] found that adolescents tended to find individual therapy more acceptable than family therapy, though their sample was also recruited from the community as opposed to a treatment-seeking, diagnosed sample. Tarnowski, Simonian, Bekeny, and Park [16] found that parents overwhelmingly preferred psychosocial treatment approaches to pharmacological approaches, regardless of depression severity. Other research on parent preferences across a range of non-depressive disorders has shown that parents tend to prefer non-pharmacological approaches [17–19] though parent preferences may vary based on prior treatment experiences. Lastly, some research has shown racial/ethnic differences in parent preferences. Chandra et al. [20] reported that Latino and African-American parents were less likely than white parents to prefer an active treatment approach, and also less likely to prefer pharmacotherapy. Importantly, preference for type of treatment has been shown to be associated with likelihood of adolescents receiving that treatment under routine care conditions [3].

Even though the results consistently show a preference for psychosocial treatment over medication, to our knowledge, there is no research assessing parent and depressed youth preferences for options within a psychosocial treatment approach for youth depression. When parent and youth preferences conflict with evidence-based research guidelines, practitioners are faced with reconciling patient preferences with the available research, a challenge facing those striving to provide evidence-based practice in psychology [21]. In order to facilitate the integration of research-based recommendations and parent and youth preferences, we must first understand what parent and youth treatment preferences are, and how treatment preferences are associated with other treatment-related constructs.

This study aims to further clarify youth and parent preferences for depression treatment, focusing on components of psychosocial treatment. Key questions addressed include: 1) how much parent involvement youth and parents prefer, and 2) how much youth and parents prefer a skills-based approach as opposed to therapy that focuses on support. Reflecting the limited research on parent and youth preferences, the present study’s goals are primarily descriptive, focused on describing rates of different preferences. In addition, we have included exploratory analyses focused on possible relationships among preferences and other demographic and psychosocial variables. As noted in research methodology texts [22], exploratory research is a necessary foundation to inform future research’s hypotheses and support future analytic designs focused on inferential statistics.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 64 youth (54.7% female, 45.3% male, 62.5% White, 26.6% Hispanic, 15.6% Black/African American, 4.7% Asian/Asian American, 17.2% multi-racial or “other”) with a mean age of 11.08 years (SD = 2.23) and 63 parents (92.1% mothers, 6.3% fathers, 1.6% grandmother)1 willing to participate in a randomized controlled trial comparing a family-focused treatment to individual psychotherapy for youth depression [23]. Of parents who reported family income (n = 62), 13% reported annual income below $30,000, 24.2% reported $30,000 to $49,999, 19.4% reported $50,000 to $74,999 (the median income range), and 43.5% reported incomes of $75,000 or more. The present sample includes all RCT participants enrolled in the study after the inclusion of the preference measure, who had a completed youth preference measure, parent preference measure, or both. Families were recruited to the study by referrals from outpatient mental health facilities, radio advertisements, advertisements in local parent magazines, print and internet advertising, and outreach to schools, Parent-Teacher Associations, pediatric offices, and other mental health treatment providers.

Procedures

After referred families were screened by telephone, participants completed a baseline evaluation to determine eligibility and clinical status. Eligible youth (a) had a diagnosis of current Major Depressive Disorder, Dysthymic Disorder, or Depressive Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified based on information obtained through the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Aged Children (K-SADS-PL; [24]) administered by project staff, (b) were 7–14 years old; (c) had a parent able and willing to provide informed consent; and (d) were able and willing to provide assent. Youth were excluded if they had a thought or other disturbance that would interfere with the ability to benefit from the intervention and participate in treatment or assessments (e.g., psychotic disorder, pervasive developmental disorder, severe OCD, active substance abuse/dependence, mental retardation), a conduct disorder that threatened the stability of the home enviromnent (e.g., recent arrests and/or juvenile justice or children’s protective service involvement) due to the potential impact on treatment implementation, or did not speak English. All study procedures were approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Boards.

Prior to randomization, both parents and youth completed a brief questionnaire on their preferences for treatment. This questionnaire is described in further detail below.

Measures

The Initial Treatment Preferences Questionnaire – Parent and Youth Versions was used to assess both parent and youth treatment preferences prior to randomization and the start of treatment. This measure is based on a pre-existing preference measure [3, 13] for consistency across research studies and consists of four items focused on preferences for psychosocial treatment vs. medication, receiving support vs. learning strategies, who meets with the therapist, and how much information is shared with the parent (see Appendix A for a copy of the measure). Participants were asked to select only one response for each item. Parents and youth were allowed to respond “don’t know” to each item, to avoid forcing them to choose a preference and to accurately estimate the proportion of parents and youth who had unclear or unformed preferences. This measure was designed for face validity, and necessarily limited in scope to constrain the time parents and youth needed to spend completing this and other study-related measures.

Two measures of youth depression symptoms were included. First, interviewers administered the Child Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R; [25]) to youth and parents. Following standard procedures, interviewers generated best-estimate ratings based on combined youth and parent infonnation. Total scores range between 17 and 113 with scores above 40 indicating a possible diagnosis of depression. The CDRS-R is the most frequently used interviewer-rated measure of youth depression symptoms in clinical trials, and demonstrated acceptable reliability in the frill study sample (17 items, α = 0.765) with a high Interclass Correlation Coefficient of 0.942. Second, both parents and youth completed the Children’s Depression Inventory - Youth and Parent Versions (CDI [26]), a self- and parent-report measure of depression symptoms in youth. Both the parent (17 items, α=0.825) and child (27 items, α=0.926) versions demonstrated good to excellent reliability.

As an indicator of youth problem behaviors, parents completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; [27]), a widely used measure of youth psychopathology that includes an externalizing symptoms scale with well-documented reliability and validity [28]. Externalizing scale T-scores are used in the present analyses.

To assess parent psychiatric symptomatology, parents completed the Behavior Symptom Inventory (BSI; [29]), a 53-item, self-report measure that yields scores of overall functioning (wellbeing) through three global indices – Global Severity Index (GSI), Positive Symptom Total (PST), and Positive Symptom Distress Index (PSDI). Items are rated on a five-point scale from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“extremely”). The GSI demonstrated excellent internal consistency in this sample (53 items, α = .961).

Two measures of family functioning were included. First, the Conflict Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; [30]) is a 20-item, self-report measure used to assess levels of conflict and negative communication within the family. The measure demonstrated excellent internal consistency in the full study sample (20 items, α = .907). Second, youth completed the Children’s Expectations of Social Behavior Questionnaire (CESBQ; [31]) as a measure of their expectations about maternal behavior. The measure includes 15 short vignettes which describe typical interactions between a youth and his/her mother and offer three possible reactions a youth may have following the interaction. Youth are asked to choose the reaction that most closely represents which response he/she would expect from his or her mother. Lower scores represent healthier relationships. Good internal consistency (15 items, α = 0.829) was obtained in the frill study sample.

Data Analytic Strategy

Consistent with the aims of the study, descriptive statistics (with accompanying inferential statistics testing for significant differences in endorsement rates) are provided for parent- and youth-endorsed preferences. Exploratory associations between variables (e.g., baseline characteristics and treatment preferences) are reported using effect sizes. To be consistent in which results are reported given space limitations, only effect sizes that are at least “small” in magnitude are reported, and interpretations are based on the estimated size of the effect. Inferential statistics and corresponding significance levels for these exploratory analyses are also reported to assist in comparability to other research. Concordance between parent and youth preferences were also tested but are not included in the results due to a lack of relationships that were at least a small effect size.

Measures of effect size used in the present study are: (1) Cohen’s w, used to test for unequal distributions of preferences across preference categories (0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 are considered small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively; [32]), (2) Cramer’s Cramer’s V (ϕc), used to test the degree to which dichotomized predictors (age, gender, and race) were related to preferences (0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 are considered small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively; [32]), and (3) the Cox and Snell pseudo R2 effect size [33], used to test the degree to which continuous predictors were related to preferences (effect sizes greater than 0.02 are considered to have met the “small” effect size criterion and are reported).

Preference measure response categories with observed frequencies below 5 were removed to avoid unintentionally biasing the results with very low-frequency responses. For preference measure items 3 & 4, response categories 2 & 3 were combined, as we considered them conceptually similar (i.e., for item 3, the combined response category represented the youth and parent(s) meeting together; for item 4, the combined response category represented the therapist speaking with the parents only with restrictions).

To highlight “take-home” findings in each set of analyses, there is a “results section summary” statement at the end of each results subsection.

Results

Overall Treatment Preferences

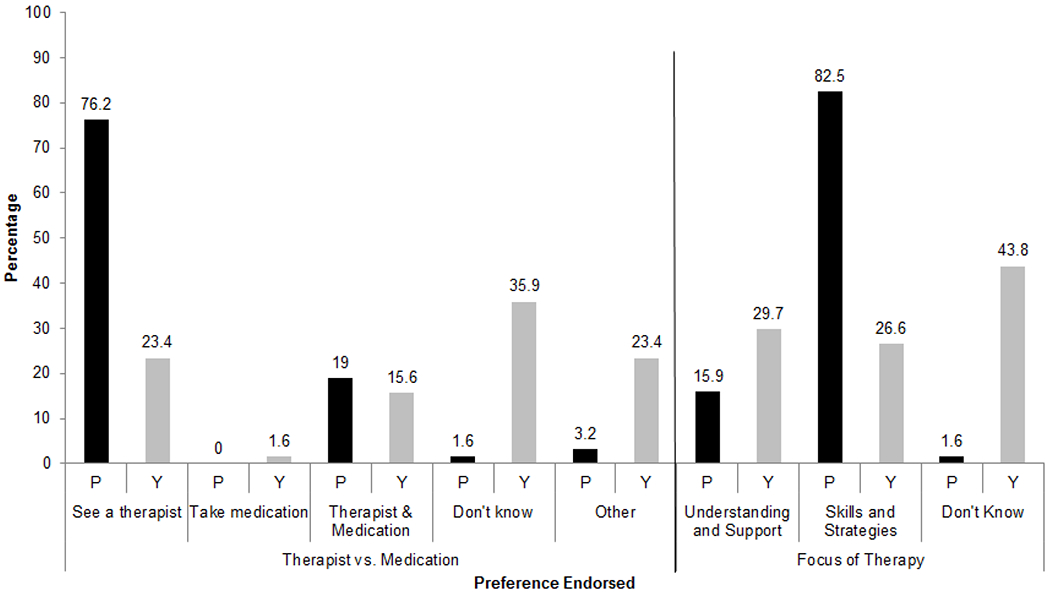

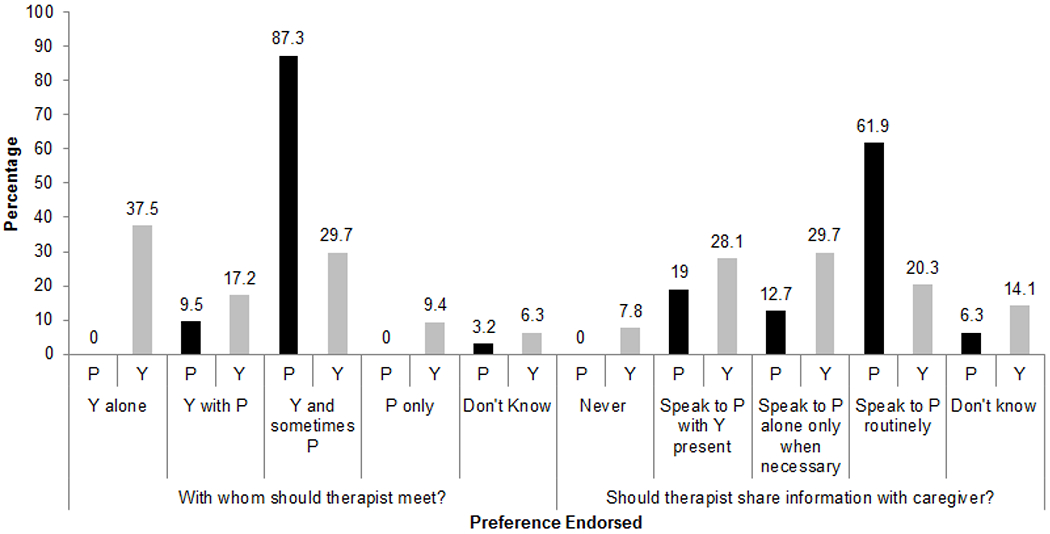

As displayed in Figs. 1 & 2, parents and youth reported multiple preferences, showing that parent and youth preferences, respectively, were unevenly distributed across response categories for therapy vs. medication (Cohen’s w = 1.446, χ2(4) = 131.683, p < .001; Cohen’s w = 0.564, χ2(4) = 20.375, p < .001), support vs. skills/strategies (Cohen’s w = 1.058, χ2(2) = 70.571, p < .001; Cohen’s w = 0.224, χ2(2) = 3.219, p = .200), who meets with the therapist (Cohen’s w = 1.692, χ2(4) = 180.254, p < .001; Cohen’s w = 0.596, χ2(4) = 22.719, p < .001), and how much information is shared with the parent (Cohen’s w = 1.095, χ2(4) = 75.492, p <.001; Cohen’s w = 0.415, χ2(4) = 11.000, p < .001).

Figure 1. Percentage of Respondents Endorsing Each Preference for Therapy Approach.

Preferences for treatment approach, including therapy versus medication and the focus of therapy, as endorsed by parents and youth. Respondent is labeled “P” for parent and “Y” for youth.

Figure 2. Percentage of Respondents Endorsing Each Preference for Parent Involvement.

Preferences for parent involvement, including whom therapist should meet with and if therapist should share information with parents, as endorsed by parents and youth. Respondent is labeled “P” for parent and “Y” for youth.

Parents, as a group, were more likely to prefer treatments that emphasized learning skills and strategies, included the parent in treatment at least some of the time, and which included speaking privately to the parent about the treatment’s progress. Youth were most likely to report that they did not know their preference for therapy vs. medication (a large effect size) or for therapy based on providing understanding and support vs. teaching skills and strategies (a small to medium, non-significant effect, suggesting a relatively even distribution across response categories with “don’t know” as the most commonly endorsed). Of those who did report a preference for therapy focus, they were evenly divided between a support-vs. skills-focused treatment. Youth were slightly more likely to prefer their parents be involved in their treatment rather than having their parents excluded (a significant, large effect size), though over a third of youth (37.5%) preferred treatment to be completely individual. A majority of youth (50.0%) preferred that the therapist speak to the parent alone at some point during treatment (a significant, medium effect size). Results section summary: parent and youth preferences varied, with parents wanting more skills- and strategies-focused treatment, and the plurality of youth responding “don’t know” to therapy focus. Both parents and youth preferred parental involvement.

Multiple potential predictors were explored, including demographic characteristics (age, gender, and race), youth symptoms (depressive symptoms and externalizing symptoms), parent symptoms, youth temperament, and family conflict.

Predictors of parent treatment preferences

Therapy vs. medication.

Multiple patterns emerged in the relationships between symptom measures and parent preferences regarding whether combined medication/psychotherapy would be helpful relative to psychotherapy alone (no parent preferred medication alone). For parents, higher parent perceptions of symptom severity were associated with a greater likelihood of preferring combined therapy. These tests produced large effect sizes on the CDI-P (Cox and Snell Pseudo R-Square = .072, Likelihood Ratio Test χ2(1) = 4.485, p = .034), CBCL Externalizing Subscale (Cox and Snell Pseudo R-Square = .096, Likelihood Ratio Test χ2(1) = 5.986, p = .014), CDRS (Cox and Snell Pseudo R-Square = .102, Likelihood Ratio Test χ2(1) = 6.434, p = .011), and also for the parent-focused BSI (Cox and Snell Pseudo R-Square = .060, Likelihood Ratio Test χ2(1) = 3.588, p = .058).

Skills vs. support.

Although parents overwhelmingly preferred a therapist who taught skills and strategies, they were even more likely to prefer skills and strategies if they reported higher levels of externalizing behaviors in their children on the CBCL (Cox and Snell Pseudo R-Square = .082, Likelihood Ratio Test χ2(1) = 5.244, p = .022). Alternatively, they were slightly more likely to prefer the therapist provide understanding and support if they were non-white (ϕc = .120, χ2(1) = 0.867, p = .349), or reported a higher level of parent symptoms on the BSI (Cox and Snell Pseudo R-Square = .057, Likelihood Ratio Test χ2(1) = 3.514, p = .061).

Treatment participants.

Parents unanimously reported a preference for at least some parent involvement in treatment.

Sharing information with parents.

No parent reported wanting to receive no information from the therapist, but parents differed on whether they would meet with the therapist with limitations (i.e., speak to the therapist privately only if there’s “a big problem” or only with the youth in the room) or no limitations (i.e., speaking with the therapist privately). Parents were slightly more likely to prefer fewer limitations on their interaction with the therapist if they were non-white (ϕc = . 148, χ2(1) = 1.277, p = .258), or there were higher ratings on the CDRS (Cox and Snell Pseudo R-Square = .039, Likelihood Ratio Test χ2(1) = 2.345, p = .126), CBQ (ϕc = .275, χ2(1) = 4.463, p = .035), or CESBQ (ϕc = .143, χ2(1) = 1.192, p = .275).

Results section summary:

Parents who reported more child depressive symptoms were more likely to prefer combined therapy and parents who reported more child externalizing behaviors were more likely to prefer therapy focus on skills and strategies.

Predictors of youth treatment preference

Therapy vs. medication.

Youth were more likely to prefer including medication if they were older (ϕc = .188, χ2(3) = 2.233, p = .526), female (ϕc = .352, χ2(3) = 7.806, p = .050), or experienced more chronic depressive symptoms (ϕc = .206, χ2(3) = 2.672, p = .445), with age resulting in only a small effect size, but gender and depression chronicity producing a medium effect size. Youth were also slightly more likely (i.e., a small effect size) to endorse “don’t know” or “other” if they were non-minority (ϕc = .135, χ2(3) = 1.152, p = .765), had above median scores on the CESBQ (ϕc = .248, χ2(3) = 3.818, p = .282), or below median scores on the CBQ (ϕc = .158, χ2(3) = 1.567, p = .667).

Skills vs. support.

The plurality of youth responded, “don’t know,” when asked about their preferences for the therapist’s approach, with boys moderately more likely to respond “don’t know” relative to girls (ϕc = .222, χ2(2) = 3.145, p = .208). Older youth were moderately more likely to prefer a therapist who provides support and understanding (ϕc = .311, χ2(2) = 6.187, p = .045), as were youth without chronic depression (ϕc = .176, χ2(2) = 1.988, p = .370). Males were moderately less likely to prefer support (ϕ = .222, χ2(2) = 3.145, p = .208). Youth were slightly more likely to prefer a therapist who teaches skills and strategies if they were non-white (ϕc = .164, χ2(2) =1.715, p = .424), or had higher scores on the CDRS (Cox and Snell Pseudo R-Square = .038, Likelihood Ratio Test χ2(2) = 2.455, p = .293), CBCL Externalizing subscale (Cox and Snell Pseudo R-Square = .022, Likelihood Ratio Test χ2(2) = 1.432, p = .489), or CESBQ (ϕc = .210, χ2(2) = 2.166, p = .251). Youth with higher CBQ scores were slightly less likely to prefer the therapist focus on skills and strategies (ϕc = .122, χ2(2) = 0.959, p = .619).

Treatment participants.

Youth were slightly more likely to prefer meeting alone with the therapist if the youth were older (ϕc = .263, χ2(2) = 4.160, p = .125), female (ϕc = .285, χ2(2) = 4.887, p = .087), or non-white (ϕc = .219, χ2(2) = 2.891, p = .236); had higher scores on the CDRS (Cox and Snell Pseudo R-Square = .070, Likelihood Ratio Test χ2(2) = 4.340, p = .114), CBQ (ϕc = .310, χ2(2) = 5.758, p = .056), CESBQ (ϕο = .169, χ2(2) = 1.717, p = .424), or CDI-C (Cox and Snell Pseudo R-Square = .042, Likelihood Ratio Test χ2(2) = 2.595, p = .273); or lower scores on the CBCL Externalizing subscale (Cox and Snell Pseudo R-Square = .026, Likelihood Ratio Test χ2(2) = 1.530, p = .465). Youth with chronic depression were slightly more likely to prefer sessions that included at least some parent participation (ϕc = .173, χ2(2) = 1.802, p = .406).

Sharing information with parents.

Youth were slightly more likely to favor limitations on parent–therapist contact if they were non-white (ϕc = .148, χ2(3) = 1.400, p = .706), older (ϕc = .137, χ2(3) = 1.196, p = .754), met criteria for chronic depression (ϕc = .154, χ2(3) = 1.520, p = .678), reported more depressive symptoms on the CDI-C (Cox and Snell Pseudo R-Square = .027, Likelihood Ratio Test χ2(3) = 1.733, p = .630), had higher scores on the CBQ (ϕc = .153, χ2(3) = 1.501, p = .682) or CESBQ (ϕc = .163, χ2(3) = 1.675, p = .643), or had parents who reported lower scores on the CBCL Externalizing subscale (Cox and Snell Pseudo R-Square = .023, Likelihood Ratio Test χ2(3) = 1.461, p = .691) or the parent-focused Brief Symptom Inventory (Cox and Snell Pseudo R-Square = .116, Likelihood Ratio Test χ2(3) = 7.673, p = .053).

Results section summary:

Stronger predictors of youth preferences included female youth being more likely to prefer including medication in treatment, older youth preferring that their therapist focus on providing support and understanding, and youth who reported more conflict in their families were more likely to want to meet alone with the therapist.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine both parent and youth preferences for depression treatments, providing important information to guide patient-centered care. Major findings with respect to parent preferences were: parents tended to have strong preferences for non-medication treatments, treatments that emphasized skills and strategies, joining in a portion of therapy sessions, and speaking regularly with their child’s therapist. In contrast, youth were often uncertain regarding what they preferred in terms of therapeutic approach (psychotherapy vs. medication; skill-building vs. support), but reported more preferences on the role their parent(s) would play during treatment with the plurality of youth preferring to meet with the therapist alone, and to have limitations on the therapist’s communication with parents. Exploratory findings also suggest that parent and youth demographics and psychosocial functioning may be associated with the preferences they endorse. There was no evidence for concordance between parent and youth preferences.

That parents are likely to report preferences is consistent with existing literature [18, 34–36]. Almost all parents chose a treatment approach that involved a therapist, with only approximately 20% of parents choosing a combined therapy and medication approach. No parents preferred medication alone. This finding is in line with other studies showing that parents are more likely to prefer psychosocial approaches over medication, possibly reflecting the variability and limits of medication effectiveness and concerns about medication safety [9, 37]. However, parents’ lack of preference for medication could also be impacted by the study design which emphasized psychosocial treatments and though continuing medication treatment was allowed (14.3% of the sample was receiving medication treatment for depression at the initial study assessment), the study did not provide medication management and families seeking medication treatment alone would not be likely to enroll in the study.

Parents were also significantly more likely to prefer the therapist teach skills and strategies compared to providing understanding and support, although a sizeable proportion of parents valued each approach. It is likely the parents who prefer that treatment focus on skills and strategies also want an understanding and supportive therapist for their child (and, vice versa, that at least a portion of parents prioritizing a therapist who provides understanding and support would also like the therapist to teach skills and strategies). Thus, the current findings suggest that the vast majority of parents would like skills and strategies included in treatment, with many of these parents prioritizing skills and strategies over understanding and support. Although current findings do not provide information on why parents are more likely to value skills and strategies over understanding and support, it is possible that parents believe active treatment is more likely to be effective, or that parent preferences are informed by public health messaging regarding evidence-based treatments (e.g., www.effectivechildtherapy.com). Fortunately, parent preferences in this sample are consistent with the emphasis on both relationship building and skill-building in CBT and other evidence-based treatments. Indeed, teaching skills and strategies is not mutually exclusive from providing understanding and support. Understanding parent preferences at the start of a treatment episode may help therapists provide information on how the available treatment options address those preferences, for example, by focusing on specific skills and strategies.

Importantly, our results indicated that parents wanted some involvement in treatment and sharing of information from the therapist (no parents reported a preference for never involving or never communicating with parents). In that context, parents also mostly preferred that the treatment include the youth (as opposed to meeting with only the parent(s)), with most preferring that the youth be the primary participant in treatment with the parent(s) only joining occasionally. These data both underscore the critical importance of some involvement of parents in delivering patient-centered care for youth depression [38, 39], and that parents want to have a role in their children’s treatment plans and be available to support their children. Here it is important to note that all parents who reported a preference on parent–therapist communication wanted to speak with the therapist, with a substantial subgroup wanting some private communication with the therapist to receive updates about their child’s therapy and possibly to receive private guidance and support in caring for their children.

Parent preferences were related, with small to moderate effect sizes, to some of the measures of participant demographics and symptoms collected at the initial assessment. Relatively few parents preferred adjunctive medication treatment, but parents were more likely to prefer adjunctive medication when they viewed their child’s symptoms as more severe (i.e., symptoms of depression and externalizing behavior) or had independent evaluators rate their children as more depressed. This finding is consistent with available data supporting the value of combined medication and psychotherapy when treating more severe depression [40].

Most parents preferred that the therapist focus on teaching skills and strategies as opposed to providing understanding and support. Parents were even more likely to prefer a skills focus if they reported more youth externalizing behaviors. Consistent with results indicating the power of enhancing parenting skills and behavior management techniques for disruptive behavior disorders [41], the disruption of externalizing behaviors may be prompting parents to endorse preferences for more active approaches (e.g., combined psychosocial and psychopharmacological treatment, skills-focused treatment). Some parent characteristics (e.g., non-White ethnicity) were associated with preferences for the therapist providing understanding and support, though the limited subsample of non-White participants and relatively modest effect sizes suggest more research is needed in this area.

Youth preferences were more evenly divided across response options, with no clear consensus preferences. There are several potential explanations for this finding. First, youth preferences may reflect a set of values (e.g., gaining autonomy versus working collaboratively) that are more heterogeneous as youth mature. Second, youth goals for treatment may have varied widely. Several youth likely agreed to participate in the study but would have preferred to abstain from treatment. In support of this explanation, over half of the youth in this sample responded “don’t know” or “other” when asked what type of treatment hey would prefer if they were sad and depressed. And a youth not wanting to seek help at all may be more likely to not report a preference, or to prefer treatment options that may appear easier, such as receiving understanding and support, or having the therapist meet only with parents. Lastly, it could be that the many “don’t know” responses and varied preferences reflect a lack of understanding on the part of some youth regarding their options. The present study did not provide any education or decision support prior to preference measurement. This omission provides a clearer picture of youth preferences before exposure to psychoeducation and decision aids, in particular, the substantial portion of youth who do not have stated preferences prior to the initiation of treatment. Developing informed preferences requires dedicated effort [42], and this is especially relevant when working with youth at varying developmental levels. This broader spread of preferences and high frequency of “don’t know” responses may, in part, explain the lack of significant effects (despite several small to moderate effect sizes) in the exploratory analyses on the relationships between youth preferences and demographic and symptom-measure variables.

The present study used a brief, face-valid measure of preferences, administered to parents and youth before they were assigned to receive a specific treatment. This measure was consistent with previous preference measurement approaches for similar (yet older) samples [3, 13], and also reflects the ways in which preferences are most often assessed – by asking patients directly what treatment they prefer to receive [43]. However, this approach may not fully capture the richness and complexity of patient preferences. Other assessment formats (e.g., preference interviews, lengthier measures assessing preferences across multiple continua; [44–46]) address these challenges, yet have not been validated for youth and parents, and are not always practically possible in a limited assessment battery.

Understanding and documenting initial preferences, which have been formed and reported on prior to psychoeducation and discussion, is important to the field and the focus of this study. These initial preferences may impact which treatments parents and youth seek out, and the degree to which they engage in a given treatment [4]. Yet preferences are not necessarily consistent or static – a client may have multiple preferences that conflict with one another, and these preferences may change over time. Treatment preferences could change following standardized education about different treatment options [47], and preferences may vary based on the available cues at the time of assessment [48]. Furthermore, some participants may have chosen not to report preferences they identified, or may have not been aware of preferences they did have. Research on preference elicitation has found that preferences may be formed through the process of values clarification [49]. In depth, idiographic, and qualitative research on youth treatment preferences is needed to enhance our understanding of the preference construct, and to reflect more accurately the ways in which preferences are assessed in clinical practice.

In this sample, parent and youth preferences did not align with each other. Published studies on parent and youth preferences have focused solely on either parent or youth preferences, so there are no direct points of comparison for the present findings, yet disagreement between parents and youth regarding the presenting problem is well-established [50]. This highlights the clinical necessity of assessing both parent and youth preferences, so neither’s preferences are neglected. This also highlights the importance of negotiating the treatment plan between parents and youth, including such treatment plan features as how often and how much therapists communicate with parents. Incorporating divergent preferences into treatment planning represents a separate challenge, focused on in work on youth shared decision-making [51]. The present findings suggest that such work is necessary in routine clinical practice and should be considered as a standard practice (e.g., a module) at the start of manual-based interventions.

There are several limitations to the present study that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the study sample was primarily White with a relatively small proportion of ethnic/racial minority families (37% non-White). Second, study participants agreed to participation in a randomized trial testing two types of psychotherapy. Families preferring medication monotherapy would not have been likely to have enrolled in the trial, and those with especially strong preferences (i.e., those unwilling to receive a non-preferred treatment) would also not have been likely to participate in the randomized trial. However, it is important to note that medication use was not an exclusion criterion, so parents may still have chosen to participate to receive psychosocial treatment. And existing research has documented a strong preference for psychosocial interventions over medication [52]. Further, study recruitment records indicate very few potential participants inquiring about the types of psychosocial treatment provided (and even fewer decided not to participate because of randomization). The study also did not ask about eHealth or mHealth interventions which are becoming increasingly available and represent a new direction in health and mental health care.

The need to acknowledge and incorporate patient preferences into treatment planning is not new. It is a key element of patient-centered care [2], evidence-based practice in psychology [21], and care delivery models such as pediatric patient-centered medical homes [1]. There is also notable work in adult populations showing that, compared to usual care, collaborative care management of depression leads to greater rates of treatment, satisfaction with care, symptom improvement, and quality of life [53], and a meta-analysis of 53 studies examining adult mental health treatment demonstrated that when providers accommodated preferences, there were fewer treatment dropouts and more positive treatment outcomes [43]. However, our understanding of parent and youth preferences is severely limited. The present study is, to the authors’ knowledge, the first to report on parent and youth preferences for variations in a psychosocial treatment approach. We found that most parents and youth had specific preferences regarding how psychosocial treatment is conducted, and some preferences tended to converge, such as parents’ preferring skills-based treatment versus a treatment focused on understanding and support. In addition to investigating broader psychosocial treatment preferences (e.g., skills/strategies vs. understanding/support), future research should also investigate preferences for specific skills and strategies (e.g., behavioral activation vs. problem solving), as this will assist in planning treatments within a specific treatment approach/orientation, and potentially lead to treatments that are more efficient and effective. The larger percentage of youth who reported no preference also highlights the potential need for mental health treatment providers across disciplines to provide information to youth regarding their treatment options. Specific interventions to assess preferences, increase patient knowledge, and collaboratively plan care (e.g., shared decision-making; [51]) may increase the likelihood that youth and parents will engage in treatment. For example, when adolescents with elevated depression symptoms who preferred “watchful waiting” received a quality improvement intervention, they were more likely to receive care [3].

Patient-centered care dictates that treatment is responsive to patient preferences when such preferences exist. Prior work has demonstrated preferences regarding psychosocial treatment versus medication. The present paper documents parent and youth preferences among psychosocial approaches. Although future research assessing parent and youth preferences across multiple treatment contexts with diverse patient populations is warranted, our findings argue that clinicians should assess preferences not just for psychosocial treatment versus medication, but for how the psychosocial treatment is conducted.

Summary

Patient-centered care requires providing care that is responsive to patient preferences, needs, and values, yet data on parent and youth treatment preferences remains sparse. This is especially true for parent and youth preferences when choosing among psychosocial treatment options (e.g., skill-based vs. supportive therapy), and specifically when choosing among treatment options for youth depression. The present study 1) identified variations in parent and youth treatment preferences, and 2) explored relationships between parent and youth demographics and psychosocial functioning, and the preferences that parents and youth endorsed. Sixty-four youth and 63 parents awaiting randomization in a clinical trial evaluating psychosocial youth depression treatments reported on their preferences for treatment approach (e.g., skills vs. support) and participants (i.e., level of parent involvement). Parents preferred treatments that emphasize learning skills and strategies (82.5%) and include the parent in treatment at least some of the time (96.8%). These preferences are in line with recommendations for evidence-based practice for youth depression. Youth preferred that the therapist meet mostly with the youth alone (67.2%) but share at least some information with parents (78.1%). Youth (43.8%) tended to respond, “don’t know” to questions about their preferred therapeutic approach. Youth likely require more dedicated effort and guidance in developing and articulating informed preferences. Understanding parent and youth preferences, especially psychosocial treatment preferences, is needed to provide high quality, patient-centered care.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH101238, principal investigator David A. Langer; MH082861, principal investigator Martha C. Tompson; MH082856, principal investigator Joan R. Asamow).

Appendix A.

Treatment Preference Measure – Parent

| This set of questions involves your views about treatment for depression. Please circle the answer that best describes your preferences in the following examples. | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | If your child were depressed, would you prefer: | a) To have your child see a therapist b) To have your child take medication c) To have your child see a therapist and take medication d) I don’t know e) Other:_________ |

| 2 | If your child went for therapy, would you prefer that the therapist focus on: | a) Providing understanding and support b) Teaching skills and strategies c) I don’t know |

| 3 | If your child went for therapy, would you rather the therapist see: | a) Your child only b) Your child together with you c) Your child, sometimes including you d) You only e) I don’t know |

| 4 | Children have different feelings about how much their parents should know about what’s going on in their therapy. Would you prefer that the therapist: | a) Never speak to you b) Speak to you, but only with your child in the room c) Speak to you alone, but only if there’s a big problem d) Speak to you alone to let you know what’s going on in therapy e) I don’t know |

Appendix B.

Treatment Preference Measure – Youth

| This set of questions involves your views about treatment for depression. Please circle the answer that best describes your preferences in the following examples. | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | If you were sad and depressed, would you prefer: | a) To see a therapist b) To take medication c) To see a therapist and take medication d) I don’t know e) Other:___________ |

| 2 | If you went for therapy, would you prefer that the therapist focus on: | a) Providing understanding and support b) Teaching skills and strategies c) I don’t know |

| 3 | If you went for therapy, would you rather the therapist see: | a) You by yourself b) You with your mom or dad c) You, but sometimes include your mom or dad d) Your parents only e) I don’t know |

| 4 | Kids have different feelings about how much their parents should know about what’s going on in their therapy. Would you prefer that the therapist: | a) Never speak to your parents b) Speak to your parents, but only with you in the room c) Speak to your parents alone, but only if there’s a big problem d) Speak to your parents alone to let them know what’s going on in therapy e) I don’t know |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

The term “parent” is used instead of a more general term (e.g., “caregiver”) because the vast majority of adult participants were parents.

References

- 1.Asarnow JR, Kolko DJ, Miranda J, Kazak AE (2017) The pediatric patient-centered medical home: innovative models for improving behavioral health. Am Psychol 72:13–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine (2001) Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. The National Academies Press, Washington DC: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rapp AM, Chavira DA, Sugar CA, Asarnow JR (2017) Integrated primary medical-behavioral health care for adolescent and young adult depression: predictors of service use in the youth partners in care trial. J Pediatr Psychol 42: 1051–1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bannon WM Jr., McKay MM (2005) Are barriers to service and parental preference match for service related to urban child mental health service use? Fam Soc 86: 30–34 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olfson M, Druss BG, Marcus SC (2015) Trends in mental health care among children and adolescents. N Engl J Med 372: 2029–2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcus M, Yasamy MT, van Ommeren M, Chisholm D, Saxena S (2012) Depression: a global public health concern. https://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/who_paper_depression_wfmh_2012.pdf

- 7.World Health Organization International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology (2000) Cross-national comparisons of the prevalences and correlates of mental disorders. Bull World Health Organ, 78: 413–426 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weersing VR, Jeffreys M, Do MT, Schwartz KTG, Bolano C (2017) Evidence base update of psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 46: 11–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, Barbe R, Birmaher B, Pincus HA et al. (2007) Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Med Assoc 297: 1683–1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birmaher B, Brent D (2007) Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46: 1503–1526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Ebesutani C, Young J, Becker KD, Nakamura BJ et al. (2011) Evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: an updated review of indicators of efficacy and effectiveness. Clin Psychol-Sci Pr 18: 154–172 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook JM, Biyanova T, Elhai J, Schnurr PP, Coyne JC (2010) What do psychotherapists really do in practice? An internet study of over 2,000 practitioners. Psychotherapy 47: 260–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaycox LH, Asarnow JR, Sherbourne CD, Rea MM, LaBorde AP, Wells KB (2006) Adolescent primary care patients’ preferences for depression treatment. Adm Policy Ment Health 33: 198–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley KL, McGrath PJ, Brannen CL, Bagnell AL (2010) Adolescents’ attitudes and opinions about depression treatment. Community Ment Health J 46: 242–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caporino NE, Karver MS (2012) The acceptability of treatments for depression to a community sample of adolescent girls. J Adolesc 35: 1237–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarnowski KJ, Simonian SJ, Bekeny P, Park A (1992) Acceptability of interventions for childhood depression. Behav Modif 16: 103–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewin AB, McGuire JF, Murphy TK, Storch EA (2014) Editorial perspective: the importance of considering parent’s preferences when planning treatment for their children–the case of childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 55: 1314–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown AM, Deacon BJ, Abramowitz JS, Dammann J, Whiteside SP (2007) Parents’ perceptions of pharmacological and cognitive-behavioral treatments for childhood anxiety disorders. Behav Res Ther 45: 819–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnston C, Hommersen P, Seipp C (2008) Acceptability of behavioral and pharmacological treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: relations to child and parent characteristics. Behav Ther 39: 22–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chandra A, Scott MM, Jaycox LH, Meredith LS, Tanielian T, Burnam A (2009) Racial/ethnic differences in teen and parent perspectives toward depression treatment. J Adolesc Health 44: 546–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.APA Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice (2006) Evidence-based practice in psychology. Am Psychol 61: 271–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kazdin AE (2016) Methodological issues and strategies in clinical research, 4th edn. American Psychological Association, Washington DC [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tompson MC, Sugar CA, Langer DA, Asarnow JR (2017) A randomized clinical trial comparing family-focused treatment and individual supportive therapy for depression in childhood and early adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 56: 515–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao UMA, Flynn C, Moreci P et al. (1997) Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36: 980–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poznanski EO, Grossman JA, Buchsbaum Y, Banegas M, Freeman L, Gibbons R (1984) Preliminary studies of the reliability and validity of the Children’s Depression Rating Scale. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 23: 191–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kovacs M (1992) Children’s depression inventory. Multi-Health System, North Tonawanda, NY [Google Scholar]

- 27.Achenbach T, Rescorla L (2001) ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. ASEBA, Burlington, VT [Google Scholar]

- 28.Achenbach TM (2009) The Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA): development, findings, theory, and applications. University of Vermont research center for children, youth, and families, Burlington, VT [Google Scholar]

- 29.Derogatis L (1975) Brief symptom inventory. National Computer Systems, Paramus [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robin AL, Foster SL (1995) The Conflict Behavior Questionnaire. Dictionary of behavioral assessment techniques. Pergamon, New York, pp 148–150 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rudolph KD, Hammen C, Burge D (1995) Cognitive representations of self, family, and peers in school‐age children: links with social competence and sociometric status. Child Dev 66: 1385–1402 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cox DR, Snell EJ (1989) Analysis of binary data, 2nd edn. Chapman and Hall, London [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brinkman WB, Epstein JN (2011) Treatment planning for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: treatment utilization and family preferences. Patient Prefer Adherence 5: 45–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cunningham CE, Deal K, Rimas H, Buchanan DH, Gold M, Sdao-Jarvie K, et al. (2008) Modeling the information preferences of parents of children with mental health problems: a discrete choice conjoint experiment. J Abnorm Child Psychol 36: 1123–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waschbusch DA, Cunningham CE, Pelham WE Jr, Rimas HL, Greiner AR, Gnagy EM,. et al. (2011) A discrete choice conjoint experiment to evaluate parent preferences for treatment of young, medication naive children with ADHD. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 40: 546–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cipriani A, Zhou X, Del Giovane C, Hetrick SE, Qin B, Whittington C, et al. (2016) Comparative efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: a network meta-analysis. Lancet 388: 881–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tompson MC, Boger KD, Asarnow JR (2012) Enhancing the developmental appropriateness of treatment for depression in youth: integrating the family in treatment. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 21: 345–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dowell KA, Ogles BM (2010) The effects of parent participation on child psychotherapy outcome: a meta-analytic review. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 39: 151–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kennard B, Silva S, Vitiello B, Curry J, Kratochvil C, Simons A, et al. (2006) Remission and residual symptoms after short-term treatment in the treatment of adolescents with depression study (TADS). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 45: 1404–1411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaminski JW, Claussen AH (2017) Evidence base update for psychosocial treatments for disruptive behaviors in children. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 46: 477–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Witteman HO, Scherer LD, Gavaruzzi T, Pieterse AH, Fuhrel-Forbis A, Dansokho SC, et al. (2016) Design features of explicit values clarification methods: a systematic review. Med Decis Making 36: 453–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swift JK, Callahan JL, Cooper M, Parkin SR (2018) The impact of accommodating client preference in psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol 74: 1924–1937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vollmer B, Grote J, Lange R, Walker C (2009) A therapy preferences interview: empowering clients by offering choices. Psychother Bull 44: 33–37 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cooper M, Norcross JC (2016) A brief, multidimensional measure of clients’ therapy preferences: the Cooper-Norcross Inventory of Preferences (C-NIP). Int J Clin Hlth Psyc 16: 87–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sandell R, Clinton D, Frövenholt J, Bragsejö M (2011) Credibility clusters, preferences, and helpfulness beliefs for specific forms of psychotherapy. Psychol Psychother-T 84: 425–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson TD, Gilbert DT (2003) Affective forecasting. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 35: 345–411 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peters E, Klein W, Kaufman A, Meilleur L, Dixon A (2013) More is not always better: intuitions about effective public policy can lead to unintended consequences. Soc Iss Policy Rev 7: 114–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fagerlin A, Pignone M, Abhyankar P, Col N, Feldman-Stewart D, Gavaruzzi T et al. (2013) Clarifying values: an updated review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 13: S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yeh M, Weisz JR (2001) Why are we here at the clinic? Parent-child (dis)agreement on referral problems at outpatient treatment entry. J Consult Clin Psychol 69: 1018–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Langer DA, Jensen-Doss A (2018) Shared decision-making in youth mental health care: using the evidence to plan treatments collaboratively. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 47: 821–831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McHugh RK, Whitton SW, Peckham AD, Welge JA, Otto MW (2013) Patient preference for psychological vs pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders: A meta-analytic review. J Clin Psychiatry 74: 595–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW, Hunkeler E, Harpole L et al. (2002) Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc 288: 2836–2845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]