Abstract

Background:

The United States and Canada are in the midst of an overdose epidemic, fueled by illicitly manufactured fentanyl. While marked differences in vulnerability to drug-related harm between men and women who use drugs is well characterized, the extent to which gender differences manifest in the present overdose crisis remains understudied. We examined differences in self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl between men and women who use drugs.

Methodology:

Data were derived from three prospective cohorts of people who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada. Survey data were extracted on individuals who self-reported having used drugs known or believed to contain fentanyl in the past 30 days between December 2016 and November 2017. We used multivariable logistic regression (MLR) to examine the relationship between self-identified gender (woman vs. man) and self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl. As a sub-analysis, correlates of self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl were identified using MLR, stratified by gender.

Results:

Of 578 eligible participants, including 219 (37.9%) women, 200 (33.2%) perceived their exposure to fentanyl as unintentional (40.2% among women and 29.0% among men). In the MLR, being a woman was positively associated with self-reported unintentional fentanyl exposure (adjusted odds ratio = 2.11; 95% confidence interval: 1.45–3.09). Among women at least daily heroin use was negatively associated with self-reported unintentional fentanyl exposure, while perceiving a high or moderate risk of overdosing on fentanyl was positively associated with outcome. Among men older age was positively associated with self-reported unintentional fentanyl exposure, while injection drug use and at least daily heroin use was negatively associated with the outcome (all p<0.05).

Conclusions:

Women were more than two times as likely to self-report they were unintentionally exposed to fentanyl compared to men. These findings highlight the urgent need to further understand experiences of gender-based risk differences and develop gender-focused interventions and policies aimed at preventing drug-related harm.

Keywords: People who use drugs, Fentanyl, Women, Gender Differences

BACKGROUND

Municipalities across the United States and Canada are experiencing rising rates of opioid overdose-related morbidity and mortality driven by the contamination of the drug supply with illicitly manufactured fentanyl and its analogues (Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, 2015). The use of the synthetic opioids, which are much more potent than heroin, have become increasingly widespread among people who use drugs (PWUD) in recent years (Vancouver Coastal Health News, 2016). In 2017, the number of opioid-related deaths in Canada was estimated to be over 4,000, with approximately 72% of those deaths involving fentanyl and fentanyl-analogues of an unknown source (Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses). In British Columbia, where the crisis has hit the hardest, a 2017 study found that one in five people who inject drugs tested positive for fentanyl exposure (Hayashi et al., 2018), with more recent data suggesting an additional increased prevalence of fentanyl exposure in this group (Hayashi et al., 2019). Furthermore in the province, official Coroner reports indicate that the substance was detected in 85% of approximately 1,500 overdose deaths in 2018 (BC Coroners Service, 2019).

Despite often being framed as a men’s health crisis, with data indicating that men represent a disproportionate number of fatal opioid overdose deaths across the United States and Canada Hedegaard, ini o, Warner, 2008, Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses, 2019a), this characterization of the overdose crisis overlooks complex gender dynamics in relation to drug-related risk and harm (Boyd et al., 2018). Gender differences between men and women who use drugs have been found to shape substance use behaviours and patterns, risk dynamics, and barriers to accessing harm reduction and addiction treatment services. A large body of evidence suggests that women who use drugs (WWUD) experience interpersonal and social structural inequities that increase their vulnerability to various forms of gender-based violence and drug-related harm (Boyd et al., 2018; Collins et al., 2018; McNeil, Shannon, Shaver, Kerr, & Small, 2014; Pinkham, Stoicescu, & Myers, 2012). With regards to drug use experience and trajectories, compared to men, women are more likely to undergo faster progression from first time drug use to dependence, be more likely to be prescribed opioids to treat pain-related conditions, and report the use of opioids to self-medicate and cope with negative emotions (Mazure & Fiellin, 2018; Torchalla, Linden, Strehlau, Neilson, & Krausz, 2014). Prevention and addiction treatment services historically oriented around the considerations and concerns of men may pose unique barriers for women seeking to engage with care (Greenfield et al.; Pinkham et al., 2012). In addition, WWUD are more likely to engage in caregiving roles and responsibilities which create barriers for women who wish to access treatment and pose challenges for disclosing substance use due to intense fear of stigma and discrimination (Campbell & Ettorre, 2011; Mazure & Fiellin, 2018; Pinkham et al., 2012).

Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside DTES) neighborhood is Canada’s largest street-based drug scene (Boyd et al., 2018; McNeil, Shannon, et al., 2014). The neighbourhood, shaped by a history of illicit drug use in the context of criminalization and marginalization (McNeil, Shannon, et al., 2014), has been severely impacted by the opioid overdose crisis. WWUD in Vancouver’s DTES experience violence in the forms of structural and everyday violence that result from gendered dynamics in the local drug scene (McNeil, Shannon, et al., 2014). Different from direct violence (e.g. physical assault, verbal attacks), structural violence is violence that is embedded within social structures and institutional processes (Rhodes et al., 2012). Everyday violence manifests in the day-to-day threats of physical and sexual assault that are rendered invisible due to their pervasiveness (Bourgois, Prince, & Moss, 2004; Scheper-Hughes, 1996). PWUD are disproportionately affected by these forms of violence as a result of unequal distribution of resources and opportunities that create and sustain their marginalized position in society. In particular, ethnographic and qualitative research has documented how structural and everyday violence manifest in gendered ways to perpetuate the subordination and harms experienced by WWUD (Bourgois et al., 2004; Boyd et al., 2018; Collins et al., 2018; Epele, 2002; McNeil, Shannon, et al., 2014; Torchalla et al., 2014). For example, violence that manifests in the form of socio-economic and structural marginalization (e.g. homelessness, criminalization and poverty) as well as women’s interactions with male partners i.e., men who control women’s resources) and sex work clients, have an immediate effect on a woman’s ability to negotiate safer sex and drug use practices (McNeil, Shannon, et al., 2014). These gendered dynamics subsequently increase WWUD’s risk of drug-related harms such as syringe sharing, transmission of blood-borne infections and overdose (McNeil, Shannon, et al., 2014; Torchalla et al., 2014).

While the marked differences in vulnerability to drug-related risk and harm between men and women who use drugs have been well characterized and the experiences of gender-based violence in the context of local drug scenes have been explored, much of this evidence is drawn prior to the influx of illicitly-manufactured fentanyl in the drug supply (Boyd et al., 2018; International AIDS Society, 2019; McNeil, Shannon, et al., 2014; Pinkham et al., 2012; Torchalla et al., 2014). At present, limited research has been conducted to understand how such gender dynamics and differences have manifested the current overdose crisis. In particular, gender-based differences in perceptions of risk and vulnerability to severe intoxication within the fentanyl-adulterated drug supply remain underexplored. Using survey data derived from a community-recruited sample of people who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada, we sought to examine potential differences in self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl between men and women who reported recent exposure to a drug known or believed to contain fentanyl. Our study objectives were to: 1) estimate the association between gender and self-reported unintentional fentanyl exposure; and 2) characterize demographic characteristics, socio-structural exposures, and drug use behaviours associated with self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl among men and women, respectively.

Despite some research from Vancouver’s DTES suggesting that the recent saturation of fentanyl in local drug markets has led to an increased willingness to use and preference for fentanyl among PWUD (Bardwell, Boyd, Tupper, & Kerr, 2019), further understanding of gender dynamics and differences in relation to self-reported fentanyl exposure in this context holds potential to inform the development of gender-focused programming and policies aimed at preventing overdose risk and drug-related harm.

METHODS

Study Participants and Design

This study draws on pooled data from three ongoing prospective Vancouver-based cohorts of people who use drugs: 1) the Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS); 2) the AIDS Care Cohort to evaluate Exposure to Survival Services (ACCESS) and the 3) At-Risk Youth Study (ARYS). All cohort participants are continually recruited through self-referral and community outreach. The VIDUS cohort includes HIV-seronegative adults who injected illegal substances in the last month before study enrollment (Wood, Stoltz, Montaner, & Kerr, 2006). The ACCESS cohort includes HIV-seropositive adults who used illegal substances other than, or in addition to cannabis in the last month before study enrollment (Wood et al., 2009). The ARYS cohort includes youth (ages 14 to 26) who used illegal substances other than, or in addition to cannabis in the last month before study enrollment (Wood et al., 2006).

All three studies use harmonized data collection and follow-up procedures that allow for the combined analysis of study participants across cohorts. At baseline and subsequent semiannual follow-ups, participants answered an interviewer-administered questionnaire obtaining detailed data on demographics characteristics, socio-structural and environmental exposures, as well as information on drug use behaviours and health-related outcomes. All study participants provided written informed consent and received an honorarium of $40 for each study visit. Ethics approval for all three cohorts were obtained from the University of British Columbia and Providence Health Care Research Ethics Boards.

Measures

The present study used data collected between December 2016 and November 2017, the first round of questionnaire administration for fentanyl-exposure related measures among active cohort participants. Eligible study participants included those who reported having used any drugs known or believed to contain fentanyl in the past 30 days. The primary outcome of interest was self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl (yes vs. no). Participants were asked, “Why did you use drugs that you knew or now believe to have contained fentanyl?”. Response options included: “Stronger or better high”, “Cheaper than other opioids including heroin and prescription pills)”, “Dope sick”, “That’s all my dealer was selling”, “Curious about the effect of fentanyl”, “Didn’t know it contained fentanyl when I used it”, and “Other”. From this question, a binary measure of self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl was defined as yes (“didn’t know [the drug] contained fentanyl when I used it”) vs. no (self-reported intentional exposure to fentanyl, including all other combined response options). While self-reports of fentanyl exposure have not been shown to be valid measures of empirical exposure to fentanyl (Amlani et al., 2015; Griswold et al., 2018), in the present study and the context of a contaminated drug supply, self-reported measures of unintentional versus intentional exposure fentanyl may elucidate perceptions of risk in relation to safety and vulnerability to drug-related harm, including severe intoxication. Our primary independent variable of interest was self-reported gender (woman vs. man). Seven transgender individuals and two gender non-binary individuals were excluded from the present analysis given the unique drug use profiles of gender and sexual minorities, and to maintain anonymity and privacy (Day, Fish, Perez-Brumer, Hatzenbuehler, & Russell, 2017).

To estimate the relationship between gender and self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl (study objective 1), we controlled for a number of covariates including key socio-structural exposures and drug use behaviours. Covariates were selected based on context-dependent knowledge of Vancouver’s DTES, as well as previously published studies on gender-based differences in socio-structural vulnerability and drug use behaviours (Boyd et al., 2018; Epele, 2002; Poole & Dell, 2005). Demographic characteristics, drug use behaviours and socio-structural exposures considered included: age (per year older), ethnicity (White vs. Non-white), recent incarceration (yes vs. no), Downtown Eastside residency (yes vs. no), experiences of physical or sexual violence (yes vs. no), engaging in sex work (yes vs. no, defined as exchanging sex for money), any injection drug use (yes vs. no), daily heroin use (yes vs. no, heroin or ‘down’ included heroin, fentanyl, speedball or goofball), daily prescription opioid use yes vs. no), daily stimulant use (yes vs. no, stimulants included cocaine, crack cocaine, crystal methamphetamine, speedball and goofball), and engagement in opioid agonist therapy (yes vs. no, defined as methadone, buprenorphine-naloxone, injectable opioid agonist therapy and slow release oral morphine).

To identify factors associated with self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl among men and women (study objective 2), in light of past literature, we considered a range of demographic characteristics, socio-structural exposures, drug use behaviours and health-related outcomes (Boyd et al., 2018; McNeil, Shannon, et al., 2014; Torchalla et al., 2014). We hypothesized that selected covariates would best elucidate gender-based profiles and differences in relation to the outcome of interest, thus highlighting avenues to inform the development of gender-focused programming and policies in current overdose crisis. Demographic characteristics and socio-structural variables considered included: age (per year older) and ethnicity (White vs. Non-white), being homeless/unstably housed (yes vs. no, being homeless/unstably housed defined as residing in a hotel room, shelter, no-fixed address, street, treatment or recovery house, jail vs. residing in a house or apartment), recent incarceration (yes vs. no), Downtown Eastside residency (yes vs. no), experiences of physical or sexual violence (yes vs. no) and engaging in sex work (yes vs. no). Since our study population is characterized by high levels of polysubstance users (Hayden et al., 2014), to better characterize a range of substance use behaviours associated with the outcome, a range of high risk substance use behaviours were considered, including: any injection drug use (yes vs. no), daily heroin use (yes vs. no), daily stimulant use (yes vs. no), any benzodiazepine use (yes vs. no) and binge alcohol use (yes vs. no, defined as using more alcohol than usual). Other drug use and health-related measures considered included: perceived susceptibility of fentanyl overdose (high/moderate risk vs. no/low risk, ascertained by asking “how high or low do you feel your risk of overdosing on fentanyl or carfentanil is?”), currently carrying Naloxone (yes vs. no), symptoms of anxiety (moderate/severe vs. none/mild, assessed through the PROMIS Anxiety Short-Form (Reeve et al., 2007) and experiences of major or persistent pain (yes vs. no, defined as pain other than minor headaches, sprains etc.).

All socio-structural exposures, drug use behaviours, and health-related measures refer to activities that took place within the past six months.

Statistical Analyses

We first examined baseline characteristics stratified by self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl using the Pearson’s Chi-squared test or Fischer’s exact tests for small cell counts) for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Next, we fit a multivariable logistic regression model adjusting for a number of covariates of interest to estimate whether gender was independently associated with self-reports unintentional exposure to fentanyl. We first fit a model containing all variables found to be significantly associated with the outcome in bivariable analysis (p<0.10, see Table 1 for variables). Coefficient values associated with gender in the full model were compared to the reduced model at each step. Variables with the smallest relative change were removed sequentially, and this iterative process was continued until the maximum change from the full model exceeded 5%. This modeling approach has been previously used elsewhere (Maldonado & Greenland, 1993; Richardson et al., 2015).

As subsequent analysis, we estimated the correlates of self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl, stratified by gender. We constructed multivariable logistic regression models using an a priori-defined statistical protocol based on the examination of the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and type III p-values (Burnham & Anderson, 2002). First, to construct the full multivariable models, we included all explanatory variables that were significantly associated with self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl in the bivariable analyses (p<0.10, see Table 2 for all variables). In step-wise manner, variables with the largest p-value were removed from the full model to construct a reduced model. AIC values of the full models and reduced models were compared, and the models with the smallest AIC value were preferred. This process was continued until final gender-stratified multivariable models with the smallest AIC values were selected.

Finally, frequencies and proportions of what drug participants believed they were sold the last time they were exposed to fentanyl were reported, stratified by self-reported unintentional fentanyl exposure status. We also reported frequencies and proportions of mutually exclusive categories of substances used in the past six months among those who self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl to understand broad categories of substances consumed by the sample in relation to the outcome. Exclusive opioid use included use of heroin, fentanyl and prescription opioid use, but no stimulants (i.e., crack/powdered cocaine or crystal methamphetamine), while exclusive stimulant use included use of any stimulants but no opioids. Combined use of opioid and stimulants included a combination of the substances described above. All p-values were two-sided. All statistical analyses were preformed using the SAS version 9.4.

RESULTS

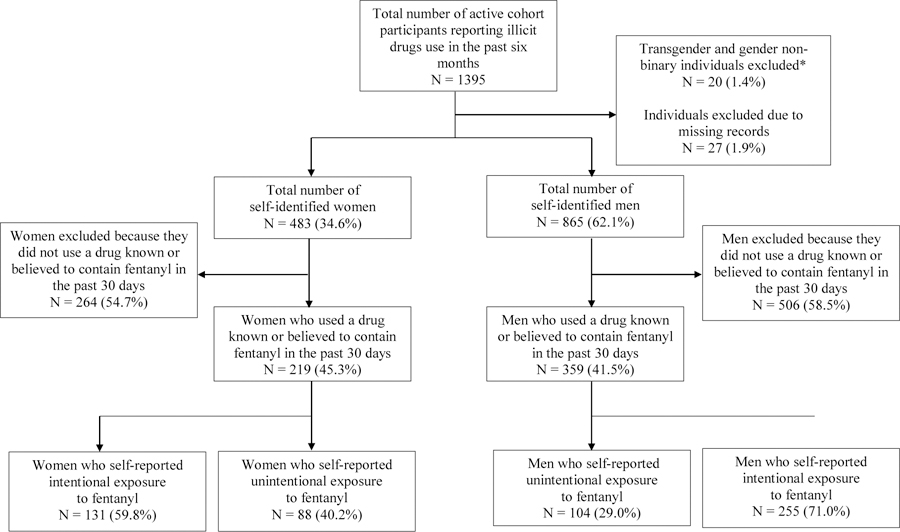

Between December 2016 and November 2017, among 1,395 active cohort participants reporting illicit drug use in the past six months, 483 (34.6%) identified as women and 865 (62.1%) identified as men. Of these, 578 (42.8%; 219 [45.3%] women and 359 [41.5%] men) self-reported using a drug known or believed to contain fentanyl in the past 30 days and were eligible for the present study. Among participants reporting recent fentanyl exposure, the median age was 41.9 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 30.6 – 52.0), 491 (84.9%) reported injection drug use in the past six months, and 192 (33.2%) reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl. The prevalence of self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl was 40.2% in women and 29.0% in men. A flow diagram of participants who self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl from the total number of cohort participants is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of study participants who self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl in a cohort of people who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada between December 2016 and November 2017.

* Transgender and gender non-binary individuals (N = 20) were excluded given the unique drug use profiles of gender and sexual minorities, and to maintain anonymity and privacy.

Table 1 represents bivariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis estimating the relationship between gender and self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl (vs. intentional exposure). In multivariable analysis, identifying as a woman remained independently and positively associated with self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.11; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.45–3.09), after adjusting for age, injection drug use and at least daily use of heroin in the past six months.

Table 1.

Bivariable and multivariable logistic regression of the association between gender and self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl in a cohort of people who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada (N=578).

| Characteristic | Self-reported Unintentional Fentanyl Exposure |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n (%) 192 (33.2) | No n (%) 386 (66.8) | Total N (%) 578 (100.0) | |||

| Gender | |||||

| Woman | 88 (45.8) | 131 (33.9) | 219 (37.9) | 1.65 (1.16– 2.35) ** | 2.11 (1.45 – 3.09) *** |

| Man | 104 (54.2) | 255 (66.1) | 359 (62.1) | ||

| Age, per year older | |||||

| (Median, IQR) | 44.7 (34.6 – 53.4) | 39 (28.2 – 50.4) | 41.9 (30.6 – 52.0) | 1.03 (1.02 – 1.05) *** | 1.03 (1.02 – 1.05) *** |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 96 (50.0) | 201 (52.5) | 297 (51.4) | 0.91 (0.64 – 1.28) | – |

| Non-white | 96 (50.0) | 182 (47.5) | 278 (48.1) | ||

| Downtown Eastside residencya | |||||

| Yes | 135 (70.3) | 243 (63.0) | 378 (65.4) | 1.39 (0.96 – 2.03) | – |

| No | 57 (29.7) | 143 (37.0) | 200 (34.6) | ||

| Incarcerationa | |||||

| Yes | 16 (8.3) | 38 (9.9) | 54 (9.3) | 0.83 (0.44 – 1.50) | – |

| No | 176 (91.7) | 347 (90.1) | 523 (90.5) | ||

| Exchanged money for sexa | |||||

| Yes | 23 (12.0) | 44 (11.4) | 67 (11.6) | 1.06 (0.61 – 1.79) | |

| No | 169 (88.0) | 342 (88.6) | 511 (88.4) | ||

| Experienced violencea | |||||

| Yes | 28 (14.6) | 52 (13.6) | 80 (13.9) | 1.08 (0.65 – 1.77) | |

| No | 164 (85.4) | 330 (86.4) | 494 (86.1) | ||

| Injection drug usea | |||||

| Yes | 155 (80.7) | 336 (87.0) | 491 (84.9) | 0.62 (0.39 – 1.00) * | 0.56 (0.34 – 0.92) * |

| No | 37 (19.3) | 50 (13.0) | 87 (15.1) | ||

| Daily heroin usea,b | |||||

| Yes | 83 (43.2) | 235 (60.9) | 318 (55.0) | 0.49 (0.34 – 0.69) *** | 0.54 (0.37 – 0.79) ** |

| No | 109 (56.8) | 151 (39.1) | 260 (45.0) | ||

| Daily prescription opioid usea | |||||

| Yes | 11 (5.7) | 14 (3.6) | 25 (4.3) | 1.61 (0.70 – 3.62) | – |

| No | 181 (94.3) | 372 (96.4) | 553 (95.7) | ||

| Daily stimulant usea,c | |||||

| Yes | 80 (41.7) | 168 (43.5) | 248 (42.9) | 0.93 (0.65 – 1.31) | – |

| No | 112 (58.3) | 218 (56.5) | 330 (57.1) | ||

| Opioid agonist therapy treatmenta | |||||

| Yes | 107 (55.7) | 227 (58.8) | 334 (57.8) | 0.88 (0.62 – 1.25) | – |

| No | 85 (44.3) | 159 (41.2) | 244 (42.2) | ||

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

reported in the last 6 months

heroin or ‘down’ includes heroin, fentanyl, speedball and goofball

stimulants include cocaine, crack cocaine, crystal methamphetamine, speedball and goofball

Table 2 represents gender-stratified bivariable and multivariable logistic regression of factors associated with self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl (vs. intentional exposure). As shown, in multivariable analysis among women, high or moderate perceived susceptibility of fentanyl overdose (AOR = 1.96; 95% CI: 1.10–3.49) was positively and independently associated with the outcome, while at least daily heroin use (AOR = 0.44; 95% CI: 0.24–0.80) was negatively and independently associated with the outcome. In multivariable analysis among men, older age (per year older, AOR = 1.04; 95% CI: 1.02–1.06) was positively and independently associated with the outcome, while injection drug use (AOR = 0..42; 95% CI: 0.23–0.76) in the past six months was negatively and independently associated with the outcome. For men, at least daily heroin use in the past six months was also negatively associated with the outcome in the bivariable model and demonstrated a similar association in the multivariable model (AOR = 0.61; 95% CI: 0.37–1.01).

Table 2.

Gender-stratified bivariable and multivariable logistic regression of factors associated with self-reported un fentanyl among a cohort of people who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada (N=578).

| Characteristic | Women (n=219) |

Men (n=359) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported Unintentional Fentanyl Exposure |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted ORd (95% CI) | Self-reported Unintentional Fentanyl Exposure |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted ORd (95% CI) | |||

| Yes n (%) 88 (40.2) | No n (%) 131 (59.8) | Yes n (%) 104 (29.0) | No n (%) 255 (71.0) | |||||

| Age, per year older | 1.03 (1.00 –1.05) * | 1.04 (1.02 – 1.06) *** | 1.04 (1.02 – 1.06) *** | |||||

| (Median, IQR) | 40.9 (33.9 – 49.7) | 36.7 (29.0 – 48.4) | – | 51.2 (35.2 – 56.1) | 41.7 (28.2 – 51.1) | |||

| Ethnicity | 0.85 (0.48 – 1.48) | – | 1.11 (0.70 – 1.78) | – | ||||

| White | 33 (37.5) | 53 (41.4) | 63 (60.6) | 148 (58.0) | ||||

| Non-white | 55 (62.5) | 75 (58.6) | 41 (39.4) | 107 (42.0) | ||||

| Incarcerationa | 1.53 (0.51 – 4.63) | – | 0.68 (0.30 – 1.43) | – | ||||

| Yes | 7 (8.0) | 7 (5.3) | 9 (8.7) | 31 (12.2) | ||||

| No | 81 (92.0) | 124 (94.7) | 95 (91.3) | 223 (87.8) | ||||

| Exchanged money for sexa | 0.88 (0.47 – 1.62) | – | 0.30 (0.02 – 1.66) | – | ||||

| Yes | 22 (25.0) | 36 (27.5) | 1 (1.0) | 8 (3.1) | ||||

| No | 66 (75.0) | 95 (72.5) | 103 (99.0) | 247 (96.9) | ||||

| Experienced violencea | 0.77 (0.34 – 1.68) | – | 1.36 (0.70 – 2.54) | – | ||||

| Yes | 11 (12.5) | 20 (15.6) | 17 (16.3) | 32 (12.6) | ||||

| No | 77 (87.5) | 108 (84.4) | 87 (83.7) | 222 (87.4) | ||||

| Downtown East Side residencya | 1.90 (1.04 – 3.57) * | 1.77 (0.93– 3.38) | 1.09 (0.68 – 1.77) | |||||

| Yes | 68 (77.3) | 84 (64.1) | 67 (64.4) | 159 (62.4) | ||||

| No | 20 (22.7) | 47 (35.9) | 37 (35.6) | 96 (37.6) | ||||

| Homeless/unstably houseda | 1.10 (0.58 – 2.10) | – | 0.92 (0.54 – 1.63) | – | ||||

| Yes | 68 (77.3) | 99 (75.6) | 81 (77.9) | 202 (79.2) | ||||

| No | 20 (22.7) | 32 (24.4) | 23 (22.1) | 53 (20.8) | ||||

| Injection drug usea | 1.01 (0.44 – 2.43) | – | 0.45 (0.26 – 0.80) ** | 0.42 (0.23 – 0.76) ** | ||||

| Yes | 78 (88.6) | 116 (88.5) | 77 (74) | 220 (86.3) | ||||

| No | 10 (11.4) | 15 (11.5) | 27 (26) | 35 (13.7) | ||||

| Daily heroin usea,b | 0.42 (0.23 – 0.73) ** | 0.44 (0.24 – 0.80) ** | 0.45 (0.28 – 0.72) ** | 0.61 (0.37 – 1.01) | ||||

| Yes | 46 (52.3) | 95 (72.5) | 37 (35.6) | 140 (54.9) | ||||

| No | 42 (47.7) | 36 (27.5) | 67 (64.4) | 115 (45.1) | ||||

| Daily stimulant usea,c | 0.90 (0.52 – 1.55) | – | 0.89 (0.56 – 1.42) | – | ||||

| Yes | 40 (45.5) | 63 (48.1) | 40 (38.5) | 105 (41.2) | ||||

| No | 48 (54.5) | 68 (51.9) | 64 (61.5) | 150 (58.8) | ||||

| Any benzodiazepine usea | 0.73 (0.19 – 2.40) | – | 1.63 (0.66 – 3.85) | – | ||||

| Yes | 4 (4.5) | 8 (6.1) | 9 (8.7) | 14 (5.5) | ||||

| No | 84 (95.5) | 123 (93.9) | 95 (91.3) | 241 (94.5) | ||||

| Binge alcohol usea | 0.81 (0.38 – 1.69) | – | 1.60 (0.86 – 2.93) | – | ||||

| Yes | 13 (14.8) | 23 (17.6) | 20 (19.2) | 33 (12.9) | ||||

| No | 75 (85.2) | 108 (82.4) | 84 (80.8) | 222 (87.1) | ||||

| Perceived risk of fentanyl overdose | 2.29 (1.31 – 4.04) ** | 1.96 (1.10– 3.49) * | 1.07 (0.67 – 1.70) | – | ||||

| High/Moderate | 55 (62.5) | 54 (40.5) | 52 (52.0) | 127 (50.4) | ||||

| Low/No | 32 (36.4) | 72 (59.5) | 48 (48.0) | 125 (49.6) | ||||

| Experienced anxiety, | 1.31 (0.73 – 2.37) | – | 0.85 (0.49 – 1.42) | – | ||||

| Severe/Moderate | 35 (43.2) | 40 (36.7) | 26 (26.3) | 69 (29.6) | ||||

| Mild/None | 46 (52.8) | 69 (63.3) | 73 (73.7) | 164 (70.4) | ||||

| Carries Narcan | 0.79 (0.41 – 1.53) | – | 0.74 (0.46 – 1.20) | – | ||||

| Yes | 67 (76.1) | 105 (80.2) | 64 (61.5) | 174 (68.2) | ||||

| No | 21 (23.9) | 26 (19.8) | 40 (38.5) | 81 (31.8) | ||||

| Major or persistent paina | 0.85 (0.49 – 1.46) | – | 1.04 (0.66 – 1.64) | – | ||||

| Yes | 39 (44.8) | 64 (48.9) | 50 (48.5) | 121 (47.6) | ||||

| No | 48 (55.2) | 67 (51.1) | 53 (51.5) | 133 (53.4) | ||||

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

reported in the last 6 months

heroin or ‘down’ includes heroin, fentanyl, speedball and goofball

stimulants include cocaine, crack cocaine, crystal methamphetamine, speedball and goofball

Table 3 represents the frequency and proportion of what drug participants believed they were sold when they were exposed to fentanyl. Among those who reported obtaining fentanyl as an opioid (e.g. heroin, fentanyl, prescription opioids), 27.5% self-reported unintentional fentanyl exposure, whereas of those who reported obtaining fentanyl as a stimulant (e.g. crack, powdered cocaine, crystal meth), 63.1% self-reported unintentional fentanyl exposure (p < 0.001). With respect to type of substances used by participants, of the 192 participants who reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl, 47 (24.5%) reported exclusive stimulant use, 32 (16.7%) reported exclusive opioid use, and 1 (0.5%) reported other substance use, while 112 (58.3%) reported combined opioid and stimulant use (data not shown).

Table 3.

Frequency and proportion of what drug participants believed they were sold when they were exposed to fentanyl (N=575).

| Drug sold as | Self-reported Unintentional Fentanyl Exposure (N=575) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n (%) 190 (33.0) | No n (%) 385 (66.0) | p-value | |

| Opioids | 131 (27.5) | 345 (72.5) | |

| Fentanyl | 0 (0.0) | 50 (100.0) | |

| Heroin | 130 (30.6) | 295 (69.4) | |

| Prescription Opioids | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Stimulants | 53 (63.1) | 31 (36.9) | <.0001* |

| Crystal methamphetamine | 19 (50.0) | 19 (50.0) | |

| Crack cocaine | 18 (78.3) | 5 (21.7) | |

| Powder cocaine | 16 (69.6) | 7 (30.4) | |

| Other | 5 (35.7) | 9 (64.3) | |

p-value for differences across broad substance categories (i.e., opioids, stimulants and other)

DISCUSSION

Among this community-recruited sample of people who self-reported recent exposure to a drug known or believed to contain fentanyl, we found that approximately a third reported that the exposure was unintentional. Being a woman was independently associated with a greater than two-fold higher odds of self-reporting that the exposure to fentanyl was unintentional (vs. intentional). Furthermore, in the gender-stratified analyses we found that among women, high or moderate perceived susceptibility of fentanyl overdose was positively associated with self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl, while at least daily heroin use was negatively associated with the outcome. For men, older age was positively associated with self-identified unintentional exposure to fentanyl, whereas injection drug use and at least daily heroin use were negatively associated with the outcome.

We note that the main focus of our study was to compare self-reported unintentional fentanyl exposure to intentional exposure, and not to determine the accuracy of exposure to fentanyl. Given that a number of studies indicate that PWUD are unable to accurately self-identify illicit fentanyl exposure as confirmed through biomarkers (e.g. urine drug screens) (Amlani et al., 2015; Ciccarone, Ondocsin, & Mars, 2017; Griswold et al., 2018), the use of self-reported measures is a major limitation of our study. In the context of continuously fluctuating illicit heroin and drug supplies, studies suggest that PWUD use a number of discernment measures to distinguish different types of heroin and the presence of illicitly manufactured fentanyl (Ciccarone et al., 2017; Mars, Ondocsin, & Ciccarone, 2018). These measures range from the perceived embodied effects of a particular substance, to assessment of its taste and colour (Ciccarone et al., 2017). While PWUDs’ common perceptions of fentanyl in the illicit drug market overlap with known effects of fentanyl pharmacodynamics e.g., a more intense ‘rush’ and a greater potency and shorter duration than the effect of heroin), research suggests that it is impossible to know whether PWUDs’ self-reports of fentanyl exposure are accurate without the testing of substances, thus highlighting the uncertainty with which we can accurately identify unintentional exposure to fentanyl among our study participants (Ciccarone et al., 2017). However, the exploration of self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl remains important, shedding insight into perceived threats to safety and vulnerability arising from challenges of obtaining drugs within a contaminated drug supply.

In light of this uncertainty, our study nonetheless has important implications in the context of the current overdose crisis. Despite the similar prevalence of recently using a drug known or believed to contain fentanyl between women and men (45.3% vs. 41.5%, respectively), we found that among those who self-reported recent exposure to a drug known or believed to contain fentanyl, women were more likely to report they were unintentionally exposed to fentanyl (vs. intentionally exposed) compared to men even after adjusting for key socio-demographic characteristics and drug use behaviours. Our finding may be in part explained by the longstanding experiences of subordination and violence navigated by WWUD in local drug scenes which directly affect women’s ability to navigate safer sex and drug use practices, thus increasing risk of a range of harms (Fairbairn, Small, Van Borek, Wood, & Kerr, 2010; Gagnon, 2017). Specifically, women’s limited control of type and amount of substances used may increase perceptions of unintentional fentanyl exposure, resulting from a heightened sense of vulnerability to severe intoxication and drug-related harm attributed to the fentanyl-adulterated drug supply (Gagnon, 2017; McNeil, Shannon, et al., 2014; Pinkham et al., 2012).

In our gender-stratified analyses, we found that self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl was associated with perceiving moderate or high risk of overdosing on fentanyl in women but not men. Previous research indicates that higher perceived susceptibility to overdose is associated with an increased odds of past non-fatal overdose (Bonar & Bohnert, 2016; Moallef et al., 2019; Rowe, Santos, Behar, & Coffin, 2016). These studies suggest that individuals with higher perceived risk of overdosing may be amenable to overdose prevention strategies (Bonar & Bohnert, 2016; Moallef et al., 2019), thus highlighting the potential of gender-focused overdose prevention programming tailored toward WWUD. However, the extent to which perceived overdose risk influences engagement with harm reduction behaviours remains largely unexplored (Moallef et al., 2019). Nonetheless, the gender-based implications of perceived fentanyl overdose risk remains noteworthy in context of our study. A recent qualitative and ethnographic study from our setting noted that in the backdrop of a contaminated drug supply, some women described being deliberately offered fentanyl-adulterated opioids (consumed unwittingly), resulting in rapid intoxication or loss of consciousness and leaving them susceptible to robbery and/or sexual assault (Boyd et al., 2018). These findings may explain how women’s perceived experiences of unintentional fentanyl exposure during the overdose crisis has heightened women’s awareness of, and vulnerability to violence and drug-related harm, including severe intoxication and overdose.

Taken together from our study findings and an existing evidence base on gender-based risk and drug-related harm (Boyd et al., 2018; McNeil, Shannon, et al., 2014; Rhodes et al., 2012; Torchalla et al., 2014), it is imperative that public health efforts addressing the overdose crisis consider gender-based risk differences into policy and practice. In Canada, safe consumption sites (SCS), including legally-sanctioned supervised injection services and unsanctioned overdose prevention sites (OPS) that have been implemented as emergency measures to reduce overdose death, have both been identified as safe spaces to consume illicitly-obtained drugs and intervene in the event of an overdose (Kerr, Mitra, Kennedy, & McNeil). Beyond a place to mitigate overdose risk, these services, particularly low-barrier, peer-run OPS models, serve as safe-havens against the violence experienced by WWUDs by means of accommodating for a range of drug use practices, maximizing access and autonomy, and fostering a sense of community and peer accountability (Boyd et al., 2018). To further meet the immediate needs of WWUD in the overdose crisis, SCSs should consider gender-informed operational and regulatory policies, including women’s only SCS or women’s specific drop-in hours, culturally attentive gender-focused training for staff, active involvement of WWUD in service provision and design, and client referrals to women’s specific programming. These approaches to SCS hold potential to minimize threats of overdose and drug related harm for WWUD by modifying risk environments, as well as provide a space for autonomy of control over quantity and quality of drugs consumed (Boyd et al., 2018; McNeil, Small, Lampkin, Shannon, & Kerr, 2014). Other gender-based considerations for harm reduction services for WWUD include women’s focused culturally attentive counselling programs and case management teams, and health and social service programming attentive to women-specific needs including reproductive health and childcare, as well as care for pain, trauma and mental health supports (Greenfield & Grella, 2009; VanHouten, Rudd, Ballesteros, & Mack, 2019).

Our findings also indicated that irrespective of gender, those using heroin or ‘down’ on a daily basis were less likely to report self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl. These findings are in line with previous studies that suggest that heroin use may be associated with fentanyl exposure (Carroll, Marshall, Rich, & Green, 2017; Hayashi et al., 2018; Kenney, Anderson, Conti, Bailey, & Stein, 2018). In the landscape of a highly fentanyl-adulterated drug supply, it is likely that routine use of and exposure to heroin among PWUD may reduce the likelihood of self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl given the majority of heroin is now expected to contain fentanyl. Research from our setting also suggests increased willingness to use and preference for fentanyl among PWUD since the recent influx of illicitly-manufactured fentanyl in local drug markets (Bardwell et al., 2019). Furthermore, in combination with the results from our descriptive sub-analyses (including Table 3) which indicate that self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl occurred more commonly among those who believe they obtained or used stimulants alone or in combination with opioids, compared to those who believed they obtained opioids or used opioids only, our findings suggest that unintentional exposure to fentanyl may be in part attributed to unexpected contamination of stimulant-fentanyl mixtures sold as stimulants. A recent study conducted in Vancouver found that 5% of those who tested positive for fentanyl confirmed through urine drug screens also reported having used only stimulants alone and not in combination with opioids (Hayashi et al., 2018). While these findings suggest that fentanyl-contaminated stimulants may be less commonly available in local drug markets compared to heroin adulterated with fentanyl, they still are circulated in the drug supply (Amlani et al., 2015; Hayashi et al., 2018; Klar et al., 2016) and may be of concern to those who use stimulants alone or in combination with opioids.

In light of these findings, a range of drug checking services, offered through existing harm reduction services including SCS, hold potential to reduce drug related-harm by providing individuals with information about the contents of their drugs to make informed decisions about their drug use (Bardwell et al., 2019). The services, predominantly implemented in the form fentanyl tests strips at the time of the present study, have been introduced as a novel public health intervention aimed at reducing harms associated with a highly toxic drug supply (Karamouzian et al., 2018). Some studies have demonstrated willingness to use and feasibility of the services in detecting fentanyl contaminated substances (Bardwell et al., 2019; Karamouzian et al., 2018b; Kennedy et al., 2018; Krieger et al., 2018; Peiper et al., 2019; Sherman et al., 2019; Tupper, McCrae, Garber, Lysyshyn, & Wood, 2018). However, a recent study also suggests that the services may be most useful where the illicit drug market is not saturated with fentanyl (i.e. the illicit stimulant market in the present study’s setting (Bardwell et al., 2019). Furthermore, despite the present lack of gender-based evaluations of the services, drug checking among WWUD may be particularly useful to mitigate uncertainty among those who perceive heightened vulnerability to drug-related harm, including severe intoxication. Future evaluations are necessary to understand how these services may be targeted towards priority groups, including women and those who use stimulants alone or in addition to opioids.

Of final note, North America’s opioid overdose crisis is in part contributed to by the introduction of highly potent and synthetic opioids into the illegal drug market. People who once had a safe and predictable source of pharmaceutical opioids or illegal heroin are now using highly intoxicating substances with unpredictable effects (Tyndall, 2018). Implementation and expansion of existing overdose-oriented harm reduction services, including SCS, opioid agonist therapy and take-home naloxone, are a necessary and critical first response. However, these harm reduction approaches can be limited in their scope and impact (Tyndall, 2018). The overdose crisis has fueled debates over drug law reform, prompting calls from some advocates and researchers to promote public health-based approaches to drug policies that support access to a legally regulated alternative drug supply (Kerr, 2019; Strike & Watson, 2019; Tyndall, 2018). Regulated alternatives may be achieved through the expansion of treatment- and prescription-based approaches such as low-barrier accessibility to hydromorphone or injectable opioid agonist therapy. However, alternatives beyond the scope of clinical-based settings are likewise necessary to ensure a safe source of drugs for those who remain at most risk to overdose-related harm (Kerr, 2019; Strike & Watson, 2019; Tyndall, 2018).

Strengths and Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, data from this study are derived from a non-random sample of PWUD in Vancouver, Canada, which may limit the generalizability of its findings. Second, this study used self-identified measures to ascertain fentanyl exposure rather than confirmed biomarkers (i.e., urine drug screens), resulting in reporting and measurement bias. Specifically, we unable to determine how participants knew they were unintentionally exposed to fentanyl as no related follow-up questions were asked. As discussed above, without testing of substances, it is impossible to know whether self-reports of fentanyl exposure are accurate. Despite numerous discernment measures used by PWUD to distinguish the presence of illicit fentanyl (Ciccarone et al., 2017; Mars et al., 2018), research suggests self-identified measures of fentanyl exposure may not be reliable (Amlani et al., 2015; Griswold et al., 2018). It is further important to acknowledge the gender-based differences in perception of risk when interpreting findings related to the self-reported outcome. Evidence indicates that compared to men, women are more likely to perceive themselves susceptible to a range of negative health consequences resulting from engaging in risky behaviours (Harris, Jenkins, & Glaser, 2006). However, research suggests that women’s perception of risk and vulnerability are shaped by environmental factors, as well as women’s past experiences of victimization, continual exposure implicit or explicit threats to safety, and fear of violence perpetrated by men (Gustafson, 1998; Smith, Torstensson, & Johansson, 2001). Self-reports of unintentional fentanyl exposure may thus reveal important gender dynamics related to perceptions of safety and drug-related harm in the current the overdose crisis. Study findings should likewise be interpreted with caution due to unobserved and unmeasured confounders not adjusted for in the analysis, including other direct measures of gender-based violence (e.g. emotional and psychological violence). Finally, no conclusions with regards to transgender or gender non-binary individuals and unintentional exposure to fentanyl can be drawn from the present study. Due to low numbers of transgender and non-binary individuals in our sample, we were unable to conduct sensitivity analyses. Given their unique risk profiles, future research is necessary to understand the experiences of opioid overdose risk among transgender persons and other gender and sexual minorities. Despite these limitations, with consideration of past research, these findings reveal nuanced gender differences, highlighting how the interplay between gender dynamics and women’s experiences of violence and subordination may affect perceptions around safety and vulnerability to drug-related harm within the current overdose crises (Boyd et al., 2018; Collins et al., 2018; McNeil, Shannon, et al., 2014; Torchalla et al., 2014).

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, in this community-based sample of people who use drugs reporting recent exposure to a drug known or believed to contain fentanyl, we found that women were more likely to perceive they were unintentionally exposed to fentanyl (vs. intentionally exposed) compared to men. These findings indicate that women may perceive heightened risk of drug-related harm in relation to the marginalized spaces they occupy in local drug scenes. There is accordingly an urgent need to develop gender-focused, culturally attentive interventions and policies aimed at meeting the needs of WWUD in the current overdose crisis. Moreover, given that we found that self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl occurred more frequently among people who believed they obtained or used stimulants alone or in combination with opioids, strategies may likewise benefit from targeting the needs of people who use stimulants and engage in polysubstance use. In the backdrop of the catastrophic crisis of opioid overdose, such tailored harm reduction approaches may hold potential to mitigate drug-related harm and overdose risk among those who believe they were unintentionally exposed to fentanyl-adulterated substances.

HIGHLIGHTS.

33% of people who use drugs self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl

Women were more than twice as likely as men to report unintentional fentanyl exposure

Daily heroin use was negatively associated with unintentional fentanyl exposure

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

None

REFERENCES

- Amlani A, McKee G, Khamis N, Raghukumar G, Tsang E, & Buxton JA (2015). Why the FUSS (Fentanyl Urine Screen Study)? A cross-sectional survey to characterize an emerging threat to people who use drugs in British Columbia, Canada. Harm Reduct J, 12, 54. doi: 10.1186/s12954-015-0088-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell G, Boyd J, Tupper KW, & Kerr T (2019). “We don’t got that kind of time, man. We’re trying to get high!”: Exploring potential use of drug checking technologies among structurally vulnerable people who use drugs. Int J Drug Policy, 71, 125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BC Coroners Service. (2019). Illicit Drug Overdose Deaths in BC - January 1st, 2009 - January 31, 2019. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/birth-adoption-death-marriage-and-divorce/deaths/coroners-service/statistical/illicit-drug.pdf

- Bonar E, & Bohnert A (2016). Perceived Severity of and Susceptibility to Overdose Among Injection Drug Users: Relationships With Overdose History. Subst Use Misuse, 51(10), 1379–1383. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2016.1168447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P, Prince B, & Moss A (2004). The Everyday Violence of Hepatitis C Among Young Women Who Inject Drugs in San Francisco. Hum Organ, 63(3), 253–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd J, Collins A, Mayer S, Maher L, Kerr T, & McNeil R (2018). Gendered violence and overdose prevention sites: a rapid ethnographic study during an overdose epidemic in Vancouver, Canada. Addiction, 113(12), 2261–2270. doi: 10.1111/add.14417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham K, & Anderson D (2002). Model Selection and Mutlimodel Inference: A Practice Information-Theoretic Approach: Springer; 2nd ed. 2002 Corr. 3rd printing 2003 edition. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell N, & Ettorre E (2011). Gendering addiction: the politics of drug treatment in a neurochemical world. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. (2015). CCENDU Bulletin: Deaths involving Fentanyl in Canada, 2009–2014. Retrieved from Ottawa, ON: https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-05/CCSA-CCENDU-Fentanyl-Deaths-Canada-Bulletin-2015-en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Carroll J, Marshall B, Rich J, & Green T (2017). Exposure to fentanyl-contaminated heroin and overdose risk among illicit opioid users in Rhode Island: A mixed methods study. Int J Drug Policy, 46, 136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarone D, Ondocsin J, & Mars SG (2017). Heroin uncertainties: Exploring users’ perceptions of fentanyl-adulterated and - substituted ‘heroin’. Int J Drug Policy, 46, 146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins A, Boyd J, Damon W, Czechaczek S, Krusi A, Cooper H, & McNeil R (2018). Surviving the housing crisis: Social violence and the production of evictions among women who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada. Health Place, 51, 174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JK, Fish JN, Perez-Brumer A, Hatzenbuehler ML, & Russell ST (2017). Transgender Youth Substance Use Disparities: Results From a Population-Based Sample. J Adolesc Health, 61(6), 729–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.06.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epele M (2002). Gender, violence and HIV: women’s survival in the streets. Cult Med Psychiatry, 26(1), 33–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn N, Small W, Van Borek N, Wood E, & Kerr T (2010). Social structural factors that shape assisted injecting practices among injection drug users in Vancouver, Canada: a qualitative study. Harm Reduct J, 7, 20. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-7-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon M (2017). It’s time to allow assisted injection in supervised injection sites. CMAJ, 189(34), E1083–e1084. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield S, Brooks A, Gordon S, Green C, Kropp K, McHugh R, … GM M (2007). Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend, 86(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield S, & Grella C (2009). What is “women-focused” treatment for substance use disorders? Psychiatr Serv, 60(7), 880–882. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.60.7.88010.1176/appi.ps.60.7.88010.1176/ps.2009.60.7.88010.1176/ps.2009.60.7.880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griswold MK, Chai PR, Krotulski AJ, Friscia M, Chapman B, Boyer EW, … Babu KM (2018). Self-identification of nonpharmaceutical fentanyl exposure following heroin overdose. Clin Toxicol (Phila), 56(1), 37–42. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2017.1339889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson P (1998). Gender differences in risk perception: theoretical and methodological perspectives. Risk Anal, 18(6), 805–811. doi: 10.1023/b:rian.0000005926.03250.c0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris C, Jenkins M, & Glaser D (2006). Gender differences in risk assessment: Why do women take fewer risks than men? Judgment and Decision Making, 1(1), 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Fairbairn N, Dong H, Milloy M, Debeck K, Wood E, & Kerr T (2019). Known and unknown exposure to fentanyl and the associatd risks among people who inject drugs in Vancouver, Canada. Paper presented at the College on Problems of Drug Dependence, San Antontio, Texas, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Milloy M, Lysyshyn M, DeBeck K, Nosova E, Wood E, & Kerr T (2018). Substance use patterns associated with recent exposure to fentanyl among people who inject drugs in Vancouver, Canada: A cross-sectional urine toxicology screening study. Drug Alcohol Depend, 183, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.10.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden A, Hayashi K, Dong H, Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Montaner JS, & Wood E (2014). The impact of drug use patterns on mortality among polysubstance users in a Canadian setting: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health, 14, 1153. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard H, ini o A, Warner M (2008). Drug overdose deaths in the United States, –2017. NCHS Data Brief, no 329. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- International AIDS Society. (2019). Women who inject drugs: overlooked, yet invisible. Retrieved from https://www.iasociety.org/Web/WebContent/File/2019_IAS_Brief_Women_who_inject_drugs.pdf

- Karamouzian M, Dohoo C, Forsting S, McNeil R, Kerr T, & Lysyshyn M (2018a). Evaluation of a fentanyl drug checking service for clients of a supervised injection facility, Vancouver, Canada. (1477–7517 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Karamouzian M, Dohoo C, Forsting S, McNeil R, Kerr T, & Lysyshyn M (2018b). Evaluation of a fentanyl drug checking service for clients of a supervised injection facility, Vancouver, Canada. Harm Reduct J, 15(1), 46. doi: 10.1186/s12954-018-0252-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy M, Scheim A, Rachlis B, Mitra S, Bardwell G, Rourke S, & Kerr T (2018). Willingness to use drug checking within future supervised injection services among people who inject drugs in a mid-sized Canadian city. Drug Alcohol Depend, 185, 248–252. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney S, Anderson B, Conti M, Bailey G, & Stein M (2018). Expected and actual fentanyl exposure among persons seeking opioid withdrawal management. J Subst Abuse Treat, 86, 65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T (2019). Public health responses to the opioid crisis in North America. J Epidemiol Community Health, 73(5), 377–378. doi: 10.1136/jech-2018-210599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Mitra S, Kennedy MC, & McNeil R (2017). Supervised injection facilities in Canada: past, present, and future. (1477–7517 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Klar SA, Brodkin E, Gibson E, Padhi S, Predy C, Green C, & Lee V (2016). Notes from the Field: Furanyl-Fentanyl Overdose Events Caused by Smoking Contaminated Crack Cocaine - British Columbia, Canada, July 15–18, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 65(37), 1015–1016. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6537a6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger MS, Yedinak JL, Buxton JA, Lysyshyn M, Bernstein E, Rich JD, … Marshall BDL (2018). High willingness to use rapid fentanyl test strips among young adults who use drugs. Harm Reduct J, 15(1), 7. doi: 10.1186/s12954-018-0213-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado G, & Greenland S (1993). Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol, 138(11), 923–936. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars SG, Ondocsin J, & Ciccarone D (2018). Sold as Heroin: Perceptions and Use of an Evolving Drug in Baltimore, MD. J Psychoactive Drugs, 50(2), 167–176. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2017.1394508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazure C, & Fiellin D (2018). Women and opioids: something different is happening here. Lancet, 392(10141), 9–11. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31203-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, Shannon K, Shaver L, Kerr T, & Small W (2014). Negotiating place and gendered violence in Canada’s largest open drug scene. Int J Drug Policy, 25(3), 608–615. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, Small W, Lampkin H, Shannon K, & Kerr T (2014). “People knew they could come here to get help”: an ethnographic study of assisted injection practices at a peer-run ‘unsanctioned’ supervised drug consumption room in a Canadian setting. AIDS Behav, 18(3), 473–485. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0540-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moallef S, Nosova E, Milloy M, DeBeck K, Fairbairn N, Wood E, … Hayashi K (2019). Knowledge of Fentanyl and Perceived Risk of Overdose Among Persons Who Use Drugs in Vancouver, Canada. Public Health Rep, 134(4), 423–431. doi: 10.1177/0033354919857084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiper NC, Clarke SD, Vincent LB, Ciccarone D, Kral AH, & Zibbell JE (2019). Fentanyl test strips as an opioid overdose prevention strategy: Findings from a syringe services program in the Southeastern United States. Int J Drug Policy, 63, 122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham S, Stoicescu C, & Myers B (2012). Developing effective health interventions for women who inject drugs: Key areas and recommendations for program development and policy. Adv Prev Med, 2012, 269123. doi: 10.1155/2012/269123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole N, & Dell C (2005). Girls, Women and Substance Use.

- Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Cook KF, Crane PK, Teresi JA, … Cella D (2007). Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Med Care, 45(5 Suppl 1), S22–31. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250483.85507.04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Wagner K, Strathdee S, Shannon K, Davidson P, & Bourgois P (2012). Structural Violence and Structural Vulnerability Within the Risk Environment: Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives for a Social Epidemiology of HIV Risk Among Injection Drug Users and Sex Workers In D. J. O’Campo P. Ed.), Rethinking Social Epidemiology. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson L, Kerr T, Dobrer S, Puskas C, Guillemi S, Montaner J, … Milloy M (2015). Socioeconomic marginalization and plasma HIV-1 RNA nondetectability among individuals who use illicit drugs in a Canadian setting. AIDS, 29(18), 2487–2495. doi: 10.1097/qad.0000000000000853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe C, Santos G, Behar E, & Coffin P (2016). Correlates of overdose risk perception among illicit opioid users. Drug Alcohol Depend, 159, 234–239. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheper-Hughes N (1996). Gender, violence and HIV: wome,’s survival in the streets. Social Science & Medicine, 43, 889–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman S, Morales K, Park J, McKenzie M, Marshall B, & Green T (2019). Acceptability of implementing community-based drug checking services for people who use drugs in three United States cities: Baltimore, Boston and Providence. Int J Drug Policy, 68, 46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith W, Torstensson M, & Johansson K (2001). Perceived Risk and Fear of Crime: Gender Differences in Contextual Sensitivity. International Review of Victimology, 8(2), 159–181. doi: 10.1177/026975800100800204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses. (2019a). National report: Apparent opioid-related deaths in Canada (January 2016 to December 2018) Web Based Report. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; Retrieved from https://health-infobase.canada.ca/datalab/national-surveillance-opioid-mortality.html [Google Scholar]

- Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses. (2019b). National report: Apparent opioid-related deaths in Canada (January 2016 to September 2018) Web Based Report. Retrieved from Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; : https://infobase.phac-aspc.gc.ca/datalab/national-surveillance-opioid-harms-mortality.html [Google Scholar]

- Strike C, & Watson T (2019). Losing the uphill battle? Emergent harm reduction interventions and barriers during the opioid overdose crisis in Canada. Int J Drug Policy, 71, 178–182. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torchalla I, Linden I, Strehlau V, Neilson E, & Krausz M (2014). “Like a lots happened with my whole childhood”: violence, trauma, and addiction in pregnant and postpartum women from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Harm Reduct J, 11, 34. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-11-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tupper K, McCrae K, Garber I, Lysyshyn M, & Wood E (2018). Initial results of a drug checking pilot program to detect fentanyl adulteration in a Canadian setting. Drug Alcohol Depend, 190, 242–245. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyndall M (2018). An emergency response to the opioid overdose crisis in Canada: a regulated opioid distribution program. CMAJ, 190(2), E35–e36. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.171060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancouver Coastal Health News. (2016). 86% of drugs checked at Insite contain fentanyl. Retrieved from http://vchnews.ca/across-vch/2016/09/01/86-drugs-checked-insite-contain-fentanyl/#.XMCtKKcZPpA

- VanHouten J, Rudd R, Ballesteros M, & Mack K (2019). Drug Overdose Deaths Among Women Aged 30–64 Years - United States, 1999–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 68(1), 1–5. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6801a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Kerr T, Marshall B, Li K, Zhang R, Hogg R, … Montaner J (2009). Longitudinal community plasma HIV-1 RNA concentrations and incidence of HIV-1 among injecting drug users: prospective cohort study. BMJ, 338, b1649. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Stoltz J, Montaner J, & Kerr T (2006). Evaluating methamphetamine use and risks of injection initiation among street youth: the ARYS study. Harm Reduct J, 3, 18. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-3-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]