Abstract

To promote HIV antiretroviral therapy (ART) outcomes in Haiti, we developed a culturally relevant intervention (InfoPlus Adherence) that combines an electronic medical record alert identifying patients at elevated risk of treatment failure and provider-delivered brief problem-solving counseling. We conducted a quasi-experimental mixed-methods study among 146 patients at two large ART clinics in Haiti with 728 historical controls. We conducted quantitative assessments of patients at baseline and intervention completion (6 months) as well as focus groups with health workers and exit interviews with patients. The primary quantitative outcome measures were HIV viral suppression according to medical record and ART adherence in terms of >=90% for “proportion of days covered” (PDC) according to pharmacy dispensing data. Results indicated that the proportion of intervention patients with suppressed VL during the study/historical periods was 80.0%/86.0% and 76.8%/87.4% for controls. In a difference-in-differences (DID) analytic model, the adjusted relative risk for viral suppression with the intervention was 1.15 (95% CI: 0.92 – 1.45, p=0.21), representing favorable but non-significant association between the intervention and the trajectory of VL outcomes. PDC >= 90% during the study/historical periods was 30.9%/11.0% among intervention participants and 16.9%/19.4% among controls. In the adjusted DID model, the relative risk for of PDC>=90% with the intervention was 4.00 (95% CI: 1.91–8.38, p<0.001), representing a highly favorable association between the intervention and the trajectory of PDC outcomes. Qualitative data affirmed acceptability of the intervention, although providers reported some challenges consistently implementing it. Future research is needed to demonstrate efficacy and explore optimal implementation strategies.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, ART, Adherence counseling, EMR, Haiti

Resumen

Para promover los resultados del tratamiento antirretroviral (TAR) en Haití, desarrollamos una intervención culturalmente relevante (Adhesión InfoPlus) que combina una alerta del registro médico electrónico que identifica a los pacientes de alto riesgo de fracaso terapéutico con un breve asesoramiento brindado por el proveedor para la resolución de problemas. Realizamos un estudio cuasi-experimental de métodos mixtos entre 128 pacientes en dos clínicas grandes del TAR en Haití con 728 controles históricos. Llevamos a cabo evaluaciones cuantitativas de los pacientes al inicio, y a la realización de la intervención (6 meses), así como grupos de enfoque con personal de salud y entrevistas de salida con los pacientes. Las medidas de resultado cuantitativas primarias fueron la supresión viral del VIH de acuerdo con la historia clínica y la adherencia al tratamiento antirretroviral en términos de > = 90% para la “proporción de días cubiertos” (PDC) según los datos de dispensación de farmacia. Los resultados indicaron que la proporción de pacientes de intervención con supresión de la carga viral (CV) durante el estudio / períodos históricos fue 80.0% / 86.0% y 76.8% / 87.4% para los controles. En un modelo analítico de diferencias en diferencias (DID), el riesgo relativo ajustado por supresión viral con la intervención fue de 1,15 (IC 95%: 0,92 a 1,45; p = 0,21), lo que representa una asociación favorable pero no significativa entre la intervención y la trayectoria de los resultados del CV. PDC> = 90% durante el estudio / períodos históricos fue 30.9% / 11.0% entre los participantes de la intervención y 16.9% / 19.4% entre los controles. En el modelo DID ajustado, el riesgo relativo de PDC> = 90% con la intervención fue de 4.00 (IC 95%: 1.91–8.38; p <0.001), lo que representa una asociación altamente favorable entre la intervención y la trayectoria de los resultados de PDC. Los datos cualitativos afirmaron la aceptabilidad de la intervención, aunque los proveedores reportaron algunos desafíos con la implementación de manera consistente. Se necesita investigación futura para demostrar eficacia y estrategias óptimas de implementación.

INTRODUCTION

Achieving HIV epidemic control globally in line with the UNAIDS 95–95-95 targets will require expanding the number of patients diagnosed with HIV, started on treatment, and achieving viral suppression. In Haiti, the poorest country in the Americas, where adult HIV prevalence is nearly 2.0% (1), approximately 75% of those who know their HIV status have started HIV antiretroviral therapy (ART).(2) However, adherence to daily ART medications remains a major challenge for patients and for Haiti’s health system, where low levels of ART adherence and retention in care as well as development of ART drug resistance have been documented (3–8). Despite the critical need, scant research in Haiti has examined ART adherence and ART adherence-promoting interventions in particular.

Well-designed electronic clinical alerts and reminders can improve quality of care and patient health outcomes in HIV care and treatment programs in both well-resourced and resource-limited settings (9–14). In resource-limited settings, EMRs offering clinical decision support have ameliorated quality of HIV care, demonstrating improvements in CD4 testing (13, 15, 16), timely initiation of ART (15), completion and timeliness of HIV diagnostic testing and nutritional evaluation among HIV-exposed and positive pediatric patients (16). However, in the context of supporting ART adherence, automated alerts and reminders may be necessary but not sufficient for providers to successfully shape positive adherence behaviors among their patients. A trial of an intervention to improve physicians’ knowledge of their patients’ adherence levels by providing them electronic drug monitoring (EDM) data demonstrated that physicians receiving EDM data were more likely to speak with patients about adherence. However, less than 10% of the communication was classified as “problem-solving” in nature, and the intervention failed to produce substantive improvements in adherence (17). Training providers in problem-based counseling approaches represents an evidence-supported strategy for improving communication with patients about adherence (18–22).

To reduce the incidence of ART treatment failure in Haiti, we initiated the InfoPlus Adherence study, which involved developing and testing a provider-focused intervention using an electronic medical record (EMR)–based alert together with brief ART adherence counseling. The intervention leverages the iSanté EMR, currently used in 120 hospitals and clinics throughout Haiti, of which more than 75 are ART sites (23, 24). It contains longitudinal health data for over 125,000 patients with HIV, including approximately two thirds of active ART patients in Haiti (7). Our preliminary research demonstrated that the rich, routinely collected iSanté data could be leveraged in a prediction algorithm to identify patients at future risk of ART treatment failure, so as to direct more intensive counseling to patients in greatest need (25). Formative work on the intervention involved refining software functionality for the EMR-base alert and a qualitative study on provider and patient beliefs and attitudes involving patient questionnaires, structured observation of ART patient visits, and focus group discussion (FGDs) with health care workers and patients (26, 27).

The purpose of this paper is to describe the InfoPlus Adherence intervention and its feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy in improving ART adherence and viral suppression in Haiti.

METHODS

InfoPlus Adherence Intervention

The first component of the InfoPlus Adherence intervention is an EMR-based alert for low ART adherence and risk of ART treatment failure, which appeared on the cover page of each patient record within the iSanté EMR system (Figure 1). Our strategy to develop the iSanté prediction algorithm was based on our previous work (25), but this time drew upon a national-level dataset with records on 69,630 ART patients. We identified a suitable prediction model by including baseline and time-varying predictors reflecting the consistency of ART medication pickups and other sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. The final selected prediction model included sex, age, marital status, time from HIV diagnosis to enrollment in HIV care and treatment, time from HIV diagnosis to ART initiation, baseline CD4 count, body mass index, World Health Organization (WHO) stage of HIV disease progression, ART regimen, ART adherence as measured by proportion of days covered (PDC) based on pharmacy dispensing data, decline of greater than 0.10 in PDC from prior period, and number of times when the patient was 3 or more days late for an ART pickup. Within the EMR, there was an automated daily calculation of a risk score, based on weighted values of the variables observed in the previous 180 days (or previous 90 days for patients with less than 180 days since ART start).

Figure 1:

iSanté Alert for Risk of Treatment Failure

Based on the risk score and results of HIV viral load testing, patients were then classified into one of five color-coded categories of risk for future treatment failure. The blue category comprised patients with evidence of a suppressed viral load test result in the past 90 days. The green, yellow, and orange categories reflected progressive levels of risk for future treatment failure when no current viral load test was available, based on tertiles of the risk score distribution. The red category comprised patients with a most-recent viral load test demonstrating a detectable value of >1,000 copies/mL. Clicking on the EMR alert generated a pop-up window where providers could view more information on the patient’s adherence history and risk characteristics, along with an explanation of the color code.

The second component of InfoPlus Adherence is a job aide with Creole language scripts demonstrating how to explain each color category to patients (Figure 2). The third component is My Adherence Stories (MAS), a five-step counseling approach according to which providers: 1) reinforce the important of ART adherence and normalize ART adherence challenges; 2) explore patient motivation for adherence; 3) ask patients to describe and compare “good days” and “bad days” with respect to taking medications; 4) work with patients to identify modifiable adherence challenges; and 5) support patients to identify feasible solutions to their challenges (Figure 3).

Figure 2:

Job Aide with Scripts for Communicating about Risk Level

Figure 3:

My Adherence Stories Counseling Approach

After developing a manualized protocol for the InfoPlus Adherence intervention and provider training modules, the Haitian and American investigator team trained 26 health workers, including doctors, nurses, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians, reception staff, and social workers in a 2-day multi-disciplinary team workshop on how to implement the intervention in practice. Community health workers received training in a separate 1-day workshop. The on-site study coordinator at the intervention site carried out on-the-job training for staff members who were unable to attend the training workshop, observed patient encounters at each stage of the patient circuit approximately monthly, and provided feedback to health workers on their application of the intervention in practice to reinforce fidelity. No formal booster training was provided.

Study Sites and Design

This was a quasi-experimental mixed-methods study with historical controls, implemented within two ART clinics in Haiti. The clinic was the unit of intervention, and both sites were large-volume outpatient ART clinics within Departmental teaching hospitals. The site randomly assigned to implement the intervention (referred to hereafter as INTR site) was in the Northern city of Cap Haitien, while the control site (referred to hereafter as CNTR site) was located in the capital city of Port-au-Prince.

At the control site, patients received ART services as they are typically delivered in Haiti. All providers had access to the EMR and were expected to periodically evaluate adherence when patients presented for care, using an existing ART adherence assessment form within the iSanté EMR, although there are no specific guidelines on expected frequency or timing of these evaluations. Prior analyses revealed that 82% of patients across all iSanté sites received at least one ART adherence assessment within their first 6 months on ART, typically provided by nurses, pharmacy technicians, or doctors (unpublished results). These providers could refer patients to a psychologist or social worker for adherence counseling if available. Standard care also included multidisciplinary team meetings to discuss support for patients with problematic adherence or signs of treatment failure. Key differences between the INTR and CNTR sites were in the monthly volume of patients newly diagnosed with HIV (14 in the INTR site vs. 20 in the CNTR site during 2016–17), in monthly volume of patients newly enrolled on ART enrolled (12 in the INTR site vs. 14 in the CNTR site during 2016–17), in the staffing for ART adherence counseling and psychosocial support services (1 social worker in the INTR site vs. 4 psychologists, 1 social worker, and trainees from the National University in the CNTR site), and the completion of viral load testing within the first year on ART (approximately 17% of patients in the INTR site and 42% of patients in the CNTR site).

The study included quantitative analyses of patient socio-demographic characteristics and health outcomes, as well as qualitative analyses of interviews held at the INTR site on the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention, including both focus group discussions (FGD) with health workers and exit interviews with patients. We sought to strengthen inference about the intervention effects by also including comparisons with historical controls from each study site, as further described below. This pilot scale, quasi-experimental study had a primary goal of assessing the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention, and a secondary goal of assessing outcomes in a preliminary fashion, to guide future work.

The study was reviewed and approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Division and the Haiti Ministry of Health National Bioethics Committee

Participant Recruitment

Research staff recruited patients during their regular clinic visits. The study focused on adult patients (>18 years of age) who had initiated ART within the past 12 months and who had returned to the clinic at least once following ART initiation. Patients were excluded from the study if they had previously received ART at another health facility, if they expected to move away from the area or travel for extended period in the ensuing 9 months, or if they could not provide informed consent. Under routine care, patients typically made monthly visits to the clinic during the first six months of treatment and then transitioned to visits at 2–6 month intervals if they were clinically stable with strong ART adherence (per clinical judgement). Study enrollment began on 12 Oct 2017 and continued through 4 May 2018, and the intervention was active from 12 Oct 2017 through 7 Sep 2018.

Since the two sites and their patient populations differed in systematic ways other than the presence of the InfoPlus Adherence intervention, we also considered historical controls from each site who met the study inclusion criteria, had started ART one year prior to study-enrolled participants at each site, and had not enrolled in the study. The timing of ART initiation and viral load outcome measurement at the INTR and CNTR sites is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4:

Study and Historical Cohort ART Start Dates and Viral Load Test Dates (INTR and CNTR)

Health care workers participating in the qualitative component of the study were regular employees working within the HIV clinic at the INTR site from seven professional cadres: doctors, clinical nurses, triage nurses, community health nurses, pharmacists, social workers, and community health agents.

Data Collection

Haitian national site-based study coordinators, all trained as psychologists and with prior professional work within HIV clinics, led data collection. Patients enrolled in the study during their existing clinic visits, completing a baseline sociodemographic questionnaire at study enrollment as well as a brief, semi-structured exit interview at study closure approximately 6 months later (median follow up 6.5 months, range 4–12 months). A professional translator translated all questionnaires from English to Haitian Creole and study staff members who were fluent in English and Haitian Creole reviewed them for fidelity of meaning. At both sites, the study coordinators contacted study participants midway through the follow-up period to encourage their continuation in the study. For patients who failed to return to the clinic at the target time for the exit interview, the study coordinators traced them in the community with assistance of lay community health workers. The study coordinators used the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tool on tablets to collect responses, and patients received a stipend of ~$6 each for the baseline and exit interviews to cover their time and transportation costs.

Data on ART initiation date, ART medication dispensing data, and viral load (VL) test orders and results came from the iSanté EMR, in which site personnel documented these data during routine practice. Study coordinators periodically reminded clinic staff to complete EMR data entry and reviewed patient files against the EMR to make sure that key data points, such as ART dispenses and HIV VL results, were captured. We also extracted paradata automatically logged within the EMR on the number of times during patient clinical encounters when health care workers clicked on the alert within the EMR patient cover page to bring up the alert “pop up” window with detailed information on the patient’s ART adherence and risk status. These clicks were automatically recorded by the iSante system, and reflected health worker engagement with the alert. EMR data were extracted from the study sites in March 2018, after closure of the study.

Participant exit interviews took place in a private office within the HIV clinic, or within a private space in a home or community setting for those who failed to return to the clinic for their regular medical appointments.

FGD with health workers at the INTR site were carried out seven months after the intervention was introduced, with separate groups for each of the seven distinct professional cadres. An experienced qualitative interviewer external to the site facilitated each FGD, using a mixture of French and Creole language based upon the preference of participants. FGDs took place within a private meeting room within the clinic. Interviews were audio recorded and translated and transcribed into French in a single step. Health workers received a stipend of ~$15 for their participation.

Measures

The primary quantitative health outcome measures were: 1) HIV VL status; 2) ART adherence in terms of “proportion of days covered” (PDC) according to pharmacy dispensing data; and 3) proportion of patients who were never more than 7 days late for an ART refill pickup (“never late”). We added the “never late” outcome to our analysis plan post hoc, because it had greater comparability across sites and time periods than the PDC measure.

VL results were characterized as suppressed at a level of <1,000 copies/ml, as outlined in Haitian national ART guidelines and the World Health Organization (WHO) consolidated ART guidelines.(28, 29) VL test results for participants during the study period reflected the first available result meeting two conditions: 1) the result occurred at least 90 days after the intervention start (on or after January 11, 2018); and 2) the result occurred 90–365 days after the patient’s ART start date. To ensure comparability, VL test results for historical cohort participants were limited to the first available result meeting similar conditions: 1) the result occurred on or after January 11, 2017 up until the study start date; and 2) the result occurred 90–365 days after the patient’s ART start date. Many patients in both historical and study periods lacked VL test results. VL testing was largely unavailable in Haiti prior to 2016 and although national clinical guidelines recommended routine VL monitoring after 6 months on ART and annually thereafter, during the time frame of the study access to VL testing was still being scaled up.(30) Patients without VL results were excluded from analysis of the VL outcome (no imputation was done for VL outcomes), but retained in the analyses of adherence outcomes.

Our two proxy measures for ART adherence were measured during the 180 days following study enrollment. For the historical comparison groups, we created a “synthetic” study enrollment date, based on an interval from ART initiation to study enrollment randomly drawn from the distribution observed among study participants at each respective clinic. The PDC measure reflected the proportion of calendar days covered by dispensed medication. We created a dichotomized PDC variable with PDC >=90% as an indicator of strong adherence. The alternative proxy measure for ART adherence was based on never being more than 7 days late for an ART refill. There was no missing data in the historical and study groups on these two adherence indicators, and results were available for participants with and without VL test results in both time periods.

Fidelity to the intervention was measured by health worker engagement with the EMR-based alert, defined as the frequency of clicking on the alert to bring up the alert “pop up” window. Qualitative FGDs covered themes related to acceptability and feasibility of the intervention, including knowledge and attitudes toward the EMR-based alert and the MAS counseling method, roles of each cadre in routine application of the intervention, challenges in implementing the intervention, and suggestions for improving the intervention design. The question guide was informed by constructs from the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)(31) and Bowen’s framework on intervention acceptability.(32)

Exit interviews with participants covered personal challenges with ART adherence, strategies for addressing the challenges, perceived support from health workers in discussing and resolving adherence challenges, satisfaction with one’s communication with health workers about ART adherence, and (for participants at the INTR site) knowledge of the InfoPlus Adherence color-coded alert and opinions of the alert.

Data Analysis

For the quantitative outcomes, we explored participant characteristics using descriptive statistics and tested for systematic differences in characteristics between study sites and between the study and historical periods. While our study was not statistically powered to test the efficacy of the intervention, we carried out inferential analyses to assess preliminary evidence of efficacy. VL results, our primary outcome measure, were not available for all patients, so we examined characteristics of patients with missing VL measures to assess for any systematic differences between patients with and without available results. Next, we compared the VL outcomes and ART adherence indictors between the sites and across time periods, using Fisher’s exact test for equality of proportions. We also conducted a difference-in-differences (DID) analysis of outcomes, comparing outcomes in the historical and study cohorts between INTR and CNTR sites. This analysis involved a generalized linear model with estimates for the effect of the presence of the intervention, of time, and of the interaction between the intervention and time, as well as adjustment for patient characteristics that were potential confounders (gender, age, WHO stage, and time since ART initiation). In the DID models, the interaction term estimates the causal effect of the intervention. The DID models used a modified Poisson regression approach to estimate incidence rate ratios (IRRs, a measure of relative risk) from binary outcomes, based on generalized linear models with a log link, a Poisson family, and robust variance (33, 34).

For the qualitative analyses, the investigator team developed a codebook to guide thematic coding. The codebook was originally based upon the interview guide and modified to add emergent codes during the coding process. Each interview transcript was first coded by a Haitian analyst (WD) and then reviewed by a second analyst (NP for the provider FGD, CC for the patient exit interviews). The two analysts discussed and agreed upon salient themes related to the research questions on acceptability and feasibility of the intervention.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

There were 146 participants enrolled in the study (81 at the INTR site and 65 at the CNTR site), and 728 participants in the historical control groups (362 at the INTR site and 366 at the CNTR site. Across the four comparison groups (INTR study, INTR historical, CNTR study, CNTR historical), the age and sex distribution of the study participants was fairly consistent, with about 60% female and median age of 36.2–37.8 years. However, there were differences in marital status, WHO stage, and socio-economic indicators across the groups (Table I). The mean duration of ART dispenses included in the PDC measure was higher at the INTR site during the study period (75.9 days) compared to the historical period (53.2 days). At the CNTR site, the mean duration of ART dispenses was lower than at the INTR site and was more similar between periods (48.6 days during the study period vs. 44.5 days during the historical period) (results not shown).

Table I.

Characteristics of HIV-Positive Patients at Intervention and Controls Sites in Haiti

| Intervention Site (INTR) | Control Site (CNTR) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Period (n=81) | Historical Period (n=362) | Study Period (n=65) | Historical Period (n=366) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 57% | 62% | 60% | 60% |

| Male | 43% | 38% | 40% | 40% |

| Age in years (median) | 36.2 | 36.4 | 37.2 | 37.8 |

| Marital Status*** | ||||

| Married/partner | 53% | 59% | 29% | 38% |

| Widow/divorce | 19% | 9% | 11% | 18% |

| Single | 23% | 24% | 32% | 27% |

| Missing | 5% | 8% | 28% | 17% |

| WHO Stage at Study*** | ||||

| Stage 1 | 33% | 22% | 60% | 46% |

| Stage 2 | 27% | 34% | 12% | 19% |

| Stage 3 | 32% | 23% | 6% | 11% |

| Stage 4 | 7% | 18% | 14% | 23% |

| Missing | 0% | 3% | 8% | 0% |

| Days since ART Start (median) | 56 | 58 | 51 | 42 |

| Days since HIV Diagnosis (median) | 69 | 138 | 63 | 266 |

| Socioeconomic Status (SES) | ||||

| Lowest quintile | 26% | NA | 22% | NA |

| 2nd quintile | 11% | NA | 20% | NA |

| 3rd quintile | 14% | NA | 22% | NA |

| 4th quintile | 9% | NA | 12% | NA |

| Highest quintile | 27% | NA | 14% | NA |

| Missing | 14% | NA | 11% | NA |

| SES Indicators | ||||

| Has electricity | 54% | NA | 68% | NA |

| Has mobile phone | 52% | NA | 43% | NA |

| Has bank account | 16% | NA | 12% | NA |

| Has flush toilet** | 41% | NA | 20% | NA |

Notes. Pearson Chi-2 test of equality of proportions was used for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables.

p<0.05.

p<0.01.

p<0.001.

Thirty-one health workers at the INTR site participated in the FGDs, including 2 doctors, 8 nurses, 4 pharmacy personnel, 2 social workers, and 15 community health workers.

VL and ART Adherence Outcomes

VL results were available for 45 out of 81 participants at the INTR site (56%) and 56 out of 65 participants at the CNTR site (86%) during the study period. There were few differences between participants with and without available VL results; however, those with VL results tended to be older than those without (mean age 39.6 years vs. 34.9 years, p=0.01) and, as would be expected, had higher PDC values (mean PDC 76.9% vs. 56.2%, p<0.001). During the historical period, VL results were available for 43 out of 362 participants at the INTR site (12%) and 143 out of 366 participants at the CNTR site (39%).

As shown in Figure 5, among the patients for whom we had VL data, the proportion with suppressed VL was similar between the INTR site (36 out of 45, 80.0%) and the control site (43 out of 56, 76.8%) during the study period p=0.44 for Fisher’s exact p value. In both INTR and CNTR sites, the proportion of patients with suppressed VL results declined during the study period compared to the historical period, but this decline was smaller in the INTR site (6.0 percentage point decline) than the CNTR site (10.6 percentage point decline). In the DID model, the adjusted relative risk for the interaction term was 1.15 (95% CI: 0.92 – 1.45, p=0.21), representing a 15% improvement in the trajectory of viral suppression associated with the INTR site (Table II).

Figure 5:

Proportion of Patients with Suppressed Viral Load (VL<1,000 copies/ml)

INTR = intervention site; CNTR = control site

Table II.

Adjusted Difference-in-Difference Models for Viral Load and Adherence Outcomes among HIV-Positive Patients in Haiti

| Suppressed Viral Load (n = 287)Ϯ | High Adherence, PDC >=90% (n = 873)¥ | High Adherence, Never >7 days late for ART pickup (n=873)¥ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | IRR (95% CI) | P value | IRR (95% CI) | P value | IRR (95% CI) | P value | |

|

Study period (ref = Historical) |

0.90 (0.77–1.05) | 0.17 | 0.82 (0.46, 1.48) | 0.52 | 0.76 (0.55, 1.05) | 0.10 | |

|

Intervention site (ref = Control site) |

0.99 (0.86–1.13) | 0.85 | 0.58 (0.40, 0.83) | <0.01 | 0.75 (0.62, 0.91) | <0.01 | |

|

Interaction (Intervention*Study period) |

1.15 (0.92–1.45) | 0.21 | 4.00 (1.91, 8.38) | <0.001 | 2.16 (1.42, 3.28) | <0.001 | |

|

Male sex (ref = Female) |

0.99 (0.90–1.10) | 0.92 | 1.06 (0.79, 1.42) | 0.69 | 1.20 (1.02, 1.41) | 0.03 | |

|

Age in years (Each add’l year) |

1.01 (1.00–1.01 | 0.01 | 1.02 (1.00, 1.03) | 0.03 | 1.01 (1.01, 1.02) | <0.001 | |

|

Pre-ART interval (Each add’l day) |

1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.35 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) | 0.06 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.03 | |

|

WHO Stage (ref = Stage 1) |

Stage 2 | 0.96 (0.87–1.07) | 0.47 | 1.33 (0.90, 1.97) | 0.16 | 0.97 (0.79, 1.20) | 0.79 |

| Stage 3 | 0.72 (0.58–0.89) | <0.01 | 0.63 (0.37, 1.10) | 0.10 | 0.79 (0.61, 1.02) | 0.08 | |

| Stage 4 | 0.75 (0.60–0.93) | 0.01 | 1.50 (1.01, 2.22) | 0.05 | 0.90 (0.72, 1.13) | 0.37 | |

| Missing | 0.82 (0.48–1.42) | 0.49 | 2.49 (1.15, 5.40) | 0.02 | 1.40 (0.86, 2.28) | 0.18 | |

Patients without VL test results excluded from analysis

One patient with missing gender excluded from analysis.

Notes. CI = Confidence Interval; IRR = incidence rate ratio, a measure of relative risk

During the study period, the proportion of patients with PDC>=90% was higher at the INTR site (25 out of 81 patients, 30.9%) compared to the CNTR site (11 out of 65 patients, 16.9%), p=0.04 by Fisher’s exact test (Figure 6A). In the INTR site, this proportion was notably higher during the study period compared to the historical control period (30.9% vs. 11.0%, p=0.002). In contrast, there was no change in proportion of patients with PDC>=90% between periods at the CNTR site (16.9% vs. 19.4%, p=0.64). In the adjusted DID model, the IRR for the interaction term of study period and intervention site was 4.00 (95% CI: 1.91 – 8.38, p<0.001) (Table II), representing a 400% improvement in the trajectory of the PDC outcome associated with the INTR site. The alternative marker of ART adherence, the proportion of patients never >7 days late for an ART refill, was also higher in the INTR site than the CNTR site (51.9% vs. 36.9%, p=0.07), and improved in the INTR site but declined in the CNTR site over the historical comparison period (Figure 6B). The adjusted DID model for the “never late” indicator also suggested a favorable association with the intervention (IRR=2.16; 95% CI: 1.42–3.28, p<0.001) (Table II).

Figure 6A:

Proportion of Patients with Strong Adherence (Proportion of Days Covered >=90%)*

INTR = intervention site; CNTR = control site; *Proportion of days covered (PDC) is based on pharmacy ART refill data during 180 days after study enrollment

Figure 6B:

Proportion of Patients Never Late for ART Pickup*

INTR = intervention site; CNTR = control site; *Not more than 7 days late from ART pickup based on expected date of return for medication refills, based on ART pickups within 180 days of study enrollment date

Fidelity of Implementation

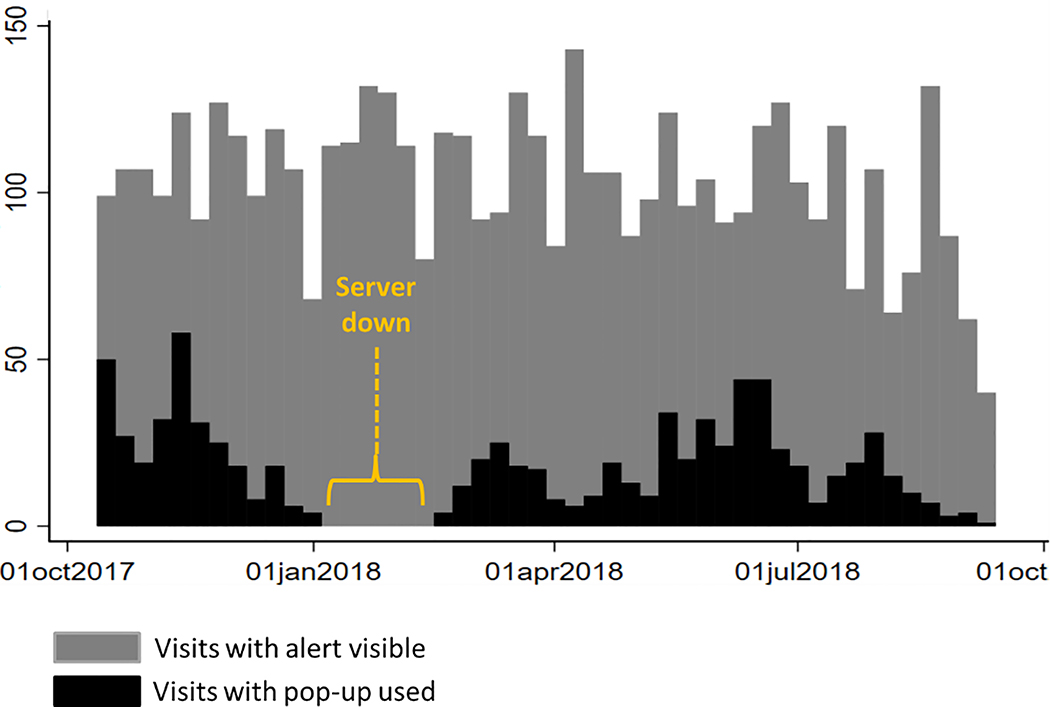

The EMR-based alert was not available during weeks 13–18 of intervention implementation, when the server for the EMR was destroyed by a power surge. It took 6 weeks for the alert functionality to be restored within the site. On average, there were 102 patients seen per week where the alert appeared on the patient’s cover page, and 19 patients per week for which the site personnel engaged with the alert by clicking on the “pop up” window (19%) (Figure 7). Engagement with the alert varied from 3% to 47% per week.

Figure 7:

EMR-Based Alert Usage by Week

Feasibility and Acceptability of the Intervention

Participants

During exit interviews, participants at the INTR site expressed overall acceptability of the intervention. They stated that the providers used the color code as a means of recognizing consistent adherence or reminding them to take their medication. About one third of participants at the INTR site reported being aware of their current color code status. Those who were not aware of their current color code status still confirmed that the clinic doctors or nurses had explained the color code to them. They stated that providers would congratulate them if their color suggested adherence, such as blue or green. Several of the participants who were in low-adherence colors, such as yellow, stated that the providers would show concern and further promote ART adherence: Yes, the doctor sent me to the Miss who told me that I have the yellow color and (she) told me that it wasn’t good for me and that I have to take my medications.

Health Care Workers

In general, health workers of all cadres perceived the InfoPlus Adherence intervention to be feasible and acceptable and described using the alert, job aide and MAS counseling approach. The understanding of the different components of the intervention were strong across all cadres of health workers: without prompting, they explained the meaning of each alert color category and talked about how they used “good days” vs. “bad days” as a conversation prompt for discussing adherence. They described counseling using the MAS approach requiring from 5 to 20 minutes. They posted the job aide on the walls of the clinic waiting room and consultation rooms, treating it a patient education tool. Community health workers as well embraced the intervention. They used a weekly visit to the clinic as an opportunity to look up the color categories of their patients on their panels within the EMR system, and then used the job aide to educate and communicate with patients about their adherence. Health workers of all cadres mentioned that they would like the EMR alert to appear for all patients, including pediatric patients and those who have been on ART for many years.

Health workers noted numerous strengths of the InfoPlus Adherence intervention, as well as challenges and recommendations for strengthening the intervention (Supplemental Appendix). They valued how the alert helped open conversations with patients about their adherence challenges, and how the alert encouraged patients to be honest about their adherence challenges.

With regards to the colors, we are more direct in our dialogue with the patient and the colors give us a lot more to say to the patient according to what they tell us about the changes in the state of their health. (Community health worker).

They appreciated that that it “ Helps you work better and go faster… because we know how to direct the counseling” (Pharmacist), and that it offered information to assess status of patient in between VL tests.

They noted that the alert seemed to motivate patients to focus on ART adherence, and that “We often hear them (patients) tell other patients to ask the providers to tell them about their color when they see them” (Pharmacist). They also valued how MAS brought about a more patient-centered approach to counseling.

…[I]t allows us to speak with the patient instead of only giving them the medications, [so] they (the patients) feel valued, and evaluating their adherence, you can go in depth about their story and know something else beyond the fact that they didn’t take their medications. (Community health nurse)

Table III contains a summary of themes from the qualitative interviews with health workers, and Supplemental Appendix includes sample quotes associated with each theme.

Table III.

Themes Related to Acceptability and Feasibility of InfoPlus Adherence

| EMR-Based Alert |

| Strengths |

| • Can open conversations about ART adherence with patients and promote honesty about adherence challenges |

| • Motivates patients to prioritize ART adherence |

| • Provides an easy overview or “early clue” about the risk level of the patient |

| • Offers objective summary of patient risk |

| • Offers information to assess status of patient between VL tests |

| • Draws the attention of providers and helps to focus counseling on patients who need it most |

| • Color categories are intuitive to understand |

| Limitations |

| • Discordance between alert value and the apparent health status of certain patients can cause doubt about the reliability of the alert |

| • Imperfect understanding of the criteria used to calculate the alert |

| • Could close off conversations |

| Recommendations |

| • Implement the alert for all patients (including pediatric & long-time ART patients) |

| • Ensure alert does not appear before 3 months on ART |

| • Improve the sensitivity and specificity of the alert |

| • Allow access to specific criteria determining patient’s color category (doctors may be more interested in this information than community health workers) |

| • Make the calendar appearing in the pop-up window more intuitive |

| • Add “adherence curve” to the patient cover page |

| • Change the red color status for unsuppressed VL result, so that it does not persist beyond three months after the VL test date; Patients who improve adherence behaviors but who remain in the red category due to a prior unsuppressed VL result may find the alert demotivating. |

| • Offer more hands-on training on use of the EMR alert and pop-up window. |

| My Adherence Stories Counseling Intervention |

| Strengths |

| • Generally good comprehension of the method |

| • Demonstrates concern for patients |

| • Encourages a patient-centered approach, focused on problem-solving |

| • Promotes a common language and approach for providers delivering adherence counseling |

| • Is feasible |

| Limitations |

| • All steps not widely implemented |

| • Without appropriate counseling, alert on its own may reduce patients’ adherence motivation |

| • Health workers still would like stronger skills in counseling patients |

| • There are many topics to cover when working with clients, so it can be difficult to prioritize adherence |

| Recommendations |

| • Provide a job aide for the five-step counseling approach |

| • Increase training and mentoring on use of the approach, particularly on helping patients to identify modifiable challenges to adherence, to generate and select a solution to try, and to check in on progress over time |

| • Need to target counseling to patients in orange or yellow categories, not only red category |

Suggestions for Improvement

Health workers and the study team noted several ways that the intervention could be improved. First, the sensitivity and specificity of the alert could be further optimized. Health workers noted that at times the alert seemed to be discordant with the patient’s true health status and risk situation, which left them in a difficult situation of trying to explain the “why” behind the color alert status. Second, some health worker’s understanding of the factors used to calculate the patient risk score and color category could have been stronger. For example, several health workers indicated a belief that patients’ sexual risk-taking contributed to their risk status, even though the EMR does not routinely capture information on sexual risk-taking behaviors and these data were not used to calculate the alert. Others perceived a contradiction between patients who appeared to be in good health but who had a concerning color status of orange or red, reflecting perhaps a limited understanding about the alert for risk of future treatment failure as opposed to present clinical decline.

Third, health workers could have more consistently used the alert and more faithfully followed the MAS five-step counseling approach. While all cadres reported using the contrast between “good days” and “bad days” as a prompt to identify adherence challenges and possible solutions, few described systematically using the last two steps in the MAS problem-solving counseling approach (identifying a specific challenge and a specific solution to try out). Health workers acknowledged that at times they were not able to apply the intervention, particularly with patients who were enrolled in community-based ART distribution and during times when the clinic was very busy. They also noted challenges to applying the intervention when the patient was too sick to engage in counseling, when the patient was accompanied in the clinic or in a community setting by people who did not know patient’s HIV status, or when they had other priority topics to address with the patient such as the need for VL monitoring or disclosure and linkage of partners to HIV testing. Several health worker cadres noted that there were many situations which they struggled to present within a modifiable adherence challenge – such as poor SES, denial of HIV and unwillingness to engage in care, lack of disclosure to household members, or strong religious beliefs leading to denial.

DISCUSSION

We successfully implemented one of the first research studies in Haiti to develop and evaluate a clinic-based intervention to promote ART adherence. The approach innovatively combined a data-driven prediction model for ART adherence and treatment failure with a brief provider-led behavioral counseling approach designed to improve ART adherence. The approach was feasible and acceptable and showed promise in terms of pharmacy-based adherence and VL outcomes, including a 15% greater likelihood of achieving viral suppression in the INTR versus the CNTR site.

While there are classical examples of prediction rules that have remained in widespread use for decades, such as the Framingham risk score for coronary heart disease (35), the Apgar score (American Academy of Pediatrics)(36), and the Glasgow coma scale (37), many tools for clinical prediction have not penetrated into routine use in clinical practice (38), and few studies have examined the use of EMR-based prediction models in clinical practice in resource-limited settings like Haiti.

While interventions using in-depth cognitive behavioral therapy have been shown to be effective in supporting ART adherence, they often depend upon highly trained personnel and require significant time. For example, in Safren’s study integrating cognitive behavioral therapy for depression with adherence counseling using the “Life-Steps” approach (CBT-AD), the intervention required Masters or Doctoral-level psychologists to conduct 11 counseling modules, each lasting up to 60 minutes (39). These types of programs would be difficult to implement at wide scale in a setting like Haiti, since many HIV care and treatment sites lack trained psychologists. The InfoPlus Adherence intervention, with its emphasis on brief, problem-solving oriented counseling, with complementary messaging and communication techniques delivered as a standard part of the patient circuit in the clinic, appeared to be a feasible method of providing ART adherence counseling using existing clinic and community-based personnel.

Bowen et al. describes several relevant constructs of feasibility including acceptability, demand, implementation, practicality, adaptation, integration, and expansion.(32) We noted acceptability, demand and practicality, with providers remarking how the intervention made it easier to rapidly gain an overview of the patient’s adherence and risk of treatment failure and how MAS brought a more systematic, consistent, and patient-centered approach to addressing adherence challenges. The intervention also reinforced a team-based approach to communicating with patients about ART adherence. However, the low fidelity of implementation (with health workers engaging with the alert during only 19% of patient encounters) underscored the need for improvements in the alert’s sensitivity, specificity and design, as well as in staff training and on-going supervision on use of the alert. That health workers reported persistent professional challenges in counseling patients when issues of denial, stigma, and lack of social support impacted ART adherence also indicated a need for more robust training on managing these situations through the MAS approach.

There were several notable ways in which the intervention was implemented and adapted that were surprising. We originally intended the intervention to be provider facing, yet health workers shared the alert color status with patients to motivate them and used the job aides as patient education tools, representing site-level adaptations. Also surprising was the strong embrace of the intervention by the community health worker (CHW) team, including their use of the alert and MAS counseling approach in their interactions with the patients in their homes and communities. CHWs were among the most supportive of the intervention, explaining in detail how it helped them to communicate with their clients about problem-solving for ART adherence.

The results of the DID model comparing HIV VL results between the INTR and CNTR sites in historical and intervention periods, suggested a more favorable trajectory for viral suppression levels at the INTR site compared to the CNTR site (though results were not statistically significant). However, the high level of missingness of VL results in both the study and historical periods strongly limits any conclusions about the trajectory of viral suppression in the overall patient population. The two ART adherence indicators (PDC and “never late”) both demonstrated a highly statistically significant and favorable association with the intervention. Together, these results suggest an improved trajectory in ART adherence at the intervention site compared with the control site. While this pilot study was not powered to detect a statistically significant difference in the VL outcome, these were encouraging results for an intervention which leveraged the existing health information system infrastructure and staffing model and did not require a significant infusion of new infrastructure or resources. Improvements to the intervention, more robust training of health workers on intervention delivery, and use of booster training to improve fidelity of implementation (which was relatively weak), could all bolster the likelihood of effectiveness if the intervention is extended to other sites in Haiti.

We acknowledge some limitations to the study. The scale and design of our study enabled us to test the intervention with a limited number of participants in only two sites, meaning that our ability to definitively measure the efficacy and certainly the effectiveness of the intervention was limited. Although the INTR clinic was randomly chosen, there were underlying differences in the patient populations and the health delivery systems between the sites. Conditions at the INTR site may have changed over time in a way that limits the strength of our pre-post inference about the effectiveness of the intervention. While we adjusted for several sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, unmeasured patient factors could have biased our results in unpredictable directions, and we were not able to disentangle the effect of changes at the INTR site between the historical and study periods from the effect of the intervention itself.

Another key limitation of the study was in the robustness of our outcome and fidelity measures. VL results were missing for a meaningful proportion of patients in both the historical and study periods, particularly at the INTR site. Our analysis of visit patterns suggests that patients without VL results were generally those who were lost to follow-up, something which did not change between the historical and study periods. However, we cannot assume that VL results were missing at random in either the historical or study periods, meaning the possibility of unpredictable bias in our results. For the adherence outcome, the PDC and “never late” indicators were proxy measures of adherence. In the current and prior studies using iSanté EMR data, PDC was highly correlated with viral suppression, consistent with studies of pharmacy-based adherence measures like PDC in other settings.(40) However, these proxies were imperfect measure of medication-taking behavior, since some patients may faithfully pick up medications from the clinic without actually taking them as prescribed. The large change in ART dispensing patterns toward multiple-month dispenses certainly biased our estimate of the effect of the intervention on PDC towards a favorable result at the INTR site, but the “never late” indicator was less subject to this bias, and reinforces the impression that ART adherence may have indeed improved at the INTR site. Finally, our measurement of fidelity of use of the intervention was limited. The metric for measuring engagement with the alert reflected only the times when health workers clicked to open the alert “pop-up,” not the times they may have viewed the alert and used it in patient management. We also lacked a measure of fidelity of use of the MAS approach, though our qualitative interviews and informal observation indicated imperfect use of the approach.

Haiti is a challenging setting for carrying out a research project such as ours. Over the course of the study, the two research sites dealt with several lengthy strikes among health workers and ancillary staff due to unpaid salaries, where the sites reduced operations for days or weeks. Server malfunction due to a power surge was another external challenge to the protocol. Periodic street demonstrations at times limited access of patients and staff from the hospital sites. For both sites, this study was the first time they participated in extramural research, and the research infrastructure, including personnel with experience in rigorous research practices, was limited.

In conclusion, the InfoPlus Adherence study demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of the iSanté EMR-based alert on risk of HIV treatment failure coupled with the MAS brief problem-solving ART adherence counseling approach. Our qualitative results demonstrated that the intervention was well understood and appreciated by both patients and health workers for the ways it made it easy for providers to gain a rapid overview of the status of ART adherence and risk of treatment failure, motivated patients, and supported honest communication between providers and patients about ART adherence challenges. Our quantitative results demonstrated a trend toward a favorable effect of the intervention on viral suppression and medication refills, although limitations of the study design argue for a cautious interpretation of this result. A larger-scale trial using a cluster randomized or stepped-wedge study design at a national level in Haiti is warranted in order to more definitively study the effectiveness of InfoPlus Adherence intervention.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the participation of clinic patients as well as the assistance with recruitment from the clinic staff.

This research was supported by NIH grants #5R34MH112378 and AI027757.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

REFERENCES

- 1.IHE. Enquête Mortalité, Morbidité et Utilisation des Services (EMMUS-VI 2016–2017) Pétion-Ville, Haïti and Rockville, Maryland, USA: Institut Haïtien de l’Enfance (IHE) and ICF; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.PEPFAR. Haiti Country Operational Plan (COP) 2018 Strategic Direction Summary. 2018.

- 3.Charles M, Noel F, Leger P, Severe P, Riviere C, Beauharnais CA, et al. Survival, plasma HIV-1 RNA concentrations and drug resistance in HIV-1-infected Haitian adolescents and young adults on antiretrovirals. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2008;86(12):970–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dionne-Odom J, Massaro C, Jogerst KM, Li Z, Deschamps MM, Destine CJ, et al. Retention in Care among HIV-Infected Pregnant Women in Haiti with PMTCT Option B. AIDS Research and Treatment. 2016;2016:6284290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hennessey KA, Leger TD, Rivera VR, Marcelin A, McNairy ML, Guiteau C, et al. Retention in Care among Patients with Early HIV Disease in Haiti. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2017;16(6):523–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auld AF, Valerie P, Robin EG, Shiraishi RW, Dee J, Antoine M, et al. Retention Throughout the HIV Care and Treatment Cascade: From Diagnosis to Antiretroviral Treatment of Adults and Children Living with HIV-Haiti, 1985–2015. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97(4_Suppl):57–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Domercant J, Puttkammer N, Young P, Yuhas K, François K, Grand’Pierre R, et al. Attrition from antiretroviral treatment services among pregnant and non-pregnant patients following adoption of Option B+ in Haiti. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1330915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puttkammer N, Domercant JW, Adler M, Yuhas K, Young P, Francois K, et al. ART Attrition and Risk Factors among Option B+ Patients in Haiti: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Plos One. 2017;12(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oluoch T, Santas X, Kwaro D, Were M, Biondich P, Bailey C, et al. The effect of electronic medical record-based clinical decision support on HIV care in resource-constrained settings: A systematic review. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2012;81(10):e83–e92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robbins G, Lester W, Johnson K, Chang Y, Estey G, Surrao D, et al. Efficacy of a Clinical Decision-Support System in an HIV Practice. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012;157(11):757–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pearson S-A, Moxey A, Robertson J, Hains I, Williamson M, Reeve J, et al. Do computerised clinical decision support systems for prescribing change practice? A systematic review of the literature (1990–2007). BMC Health Services Research. 2009;9(154):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damiani G, Pinnarelli L, Colosimo SC, Almiento R, Sicuro L, Galasso R, et al. The effectiveness of computerized clinical guidelines in the process of care: a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research. 2010;10(2):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Were MC, Shen C, Tierney WM, Mamlin JJ, Biondich PG, Li X, et al. Evaluation of computergenerated reminders to improve CD4 laboratory monitoring in sub-Saharan Africa: a prospective comparative study. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2011;18(2):150–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitahata MM, Dillingham PW, Chaiyakunapruk N, Buskin SE, Jones JL, Harrington RD, et al. Electronic Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Clinical Reminder System Improves Adherence to Practice Guidelines among the University of Washington HIV Study Cohort. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2003;36:803–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oluoch T, Kwaro D, Ssempijja V, Katana A, Langat P, Okeyo N, et al. Better adherence to pre-antiretroviral therapy guidelines after implementing an electronic medical record system in rural Kenyan HIV clinics: a multicenter pre–post study. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Were MC, Nyandiko WM, Huang KTL, Slaven JE, Shen C, Tierney WM, et al. Computer-Generated Reminders and Quality of Pediatric HIV Care in a Resource-Limited Setting. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):e789–e96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson IB, Barton Laws M, Safren SA, Lee Y, Lu M, Coady W, et al. Provider-Focused Intervention Increases Adherence-Related Dialogue but Does Not Improve Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence in Persons With HIV. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;53(3):338–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simoni JM, Amico KR, Pearson CR, Malow R. Strategies for Promoting Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy: A Review of the Literature. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2008;10(6):515–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Cargill VA, Chang LW, Gross R, et al. Guidelines for Improving Entry Into and Retention in Care and Antiretroviral Adherence for Persons With HIV: Evidence-Based Recommendations From an International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care Panel Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(11):817–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levy RW, Rayner CR, Farley CK, Kong CM, Mijch A, Costello K, et al. Multidisciplinary HIV Adherence Intervention: A Randomized Study. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2004;18(12):728–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabin LL, DeSilva MB, Hamer DH, Xu K, Zhang J, Li T, et al. Using Electronic Drug Monitor Feedback to Improve Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy Among HIV-Positive Patients in China. Aids and Behavior. 2009;14(3):580–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milam J, Richardson JL, McCutchan A, Stoyanoff S, Weiss J, Kemper C, et al. Effect of a Brief Antiretroviral Adherence Intervention Delivered by HIV Care Providers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40:356–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matheson AI, Baseman JG, Wagner SH, O’Malley GE, Puttkammer NH, Emmanuel E, et al. Implementation and expansion of an electronic medical record for HIV care and treatment in Haiti: an assessment of system use and the impact of large-scale disruptions. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2012;81(4):244–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lober W, Quiles C, Wagner S, Cassagnol R, Lamothes R, Alexis D, et al. Three years experience with the implementation of a networked electronic medical record in Haiti. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings 2008;Nov 6:434–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puttkammer N, Zeliadt S, Balan JG, Baseman J, Destiné R, Domerçant JW, et al. Development of an Electronic Medical Record Based Alert for Risk of HIV Treatment Failure in a Low-Resource Setting. Plos One. 2014;9(11):e112261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simoni J, Chéry M, Demes A, Balan JG, Haight L, Dubé JG, Genna W, Puttkammer N. Formative Research on a Provider-Delivered EMR Alert-based ART Adherence Counseling Program in Haiti: InfoPlus Adherence. International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care Conference; June 4–6; Miami, FL2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haight L PN, Chéry JM, Dervis W, Jules M, Genna W, Dubé JG, Calixte G, Balan JG, Honoré JG, Simoni J. ART adherence information, motivation, and behaviors and provider-patient relationships among new ART patients in Haiti. International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care Conference; June 8–10; Miami FL2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.MSPP. Directives unifiées pour la Prise en Charge Clinique, Thérapeutique et Prophylactique des personnes à risque et infectées par le VIH en Haiti. Port-au-Prince, Haiti: Haiti Ministry of Health and Population (MSPP); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.WHO. Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Barnhart S, Desforges G, Robin E, Francois K, Deas J, et al. Expanded Access to Viral Load Testing and Use of Second Line Regimens in Haiti: Time Trends from 2010–17., in press. BMC Infectious Diseases 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009;4:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, Cofta-Woerpel L, Linnan L, Weiner D, et al. How We Design Feasibility Studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;36(5):452–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou G A Modified Poisson Regression Approach to Prospective Studies with Binary Data. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;159(7):702–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yelland LN, Salter AB, Ryan P. Performance of the Modified Poisson Regression Approach for Estimating Relative Risks From Clustered Prospective Data. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2011;174(8):984–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suka M, Sugimori H, Yoshida K. Application of the updated Framingham risk score to Japanese men. Hypertension Research. 2001;24(6):685–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newborn AAoPCoFa, Practice ACoOaGCoO. The Apgar Score. Pediatrics. 2015;136(4):819–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braine M, Cook N. The Glasgow Coma Scale and evidence-informed practice: a critical review of where we are and where we need to be. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26:280–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collins G, de Groot J, Dutton S, Omar O, Shanyinde M, Tajar A, et al. External validation of multivariable prediction models: a systematic review of methodological conduct and reporting. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(40). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Safren SA, Bedoya CA, O’Cleirigh C, Biello KB, Pinkston MM, Stein MD, et al. Treating Depression and Adherence (CBT-AD) in Patients with HIV in Care: A Three-arm Randomized Controlled Trial. Lancet HIV. 2016;3(11):e529–e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ross-Degnan D, Pierre-Jacques M, Zhang F, Tadeg H, Gitau L, Ntaganira J, et al. Measuring adherence to antiretroviral treatment in resource-poor settings: The clinical validity of key indicators. BMC Health Services Research. 2010;10(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.