Abstract

Odontogenic myxomas often have a distinctive radiographic presentation described as a “soap bubble”, “tennis racket”, or “honeycomb” pattern. Less frequently, examples of odontogenic myxomas with a “sunray” or “sunburst” pattern have been reported. Because malignant entities such as osteosarcomas more classically present with a sunray/sunburst appearance, odontogenic myxomas are rarely considered in the radiographic differential diagnosis of a sunburst lesion. The objective of this paper is to report a case of an odontogenic myxoma presenting with a sunburst appearance and to review similar reported cases in the literature. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this additional case of an odontogenic myxoma presenting with a sunburst appearance brings the total number of sunray/sunburst cases reported in the English language literature to 21.

Keywords: Odontogenic tumor, Myxoma, Radiography, Diagnostic imaging, Sunray, Sunburst

Introduction

The odontogenic myxoma (OM) is a benign, intraosseous neoplasm that arises from odontogenic ectomesenchyme [1]. Histologically, the OM resembles the dental papilla and consists of stellate, spindle-shaped, and round cells with long, pale cytoplasmic processes [1–3]. These cells are evenly distributed in an abundant and loose myxoid stroma containing varying amounts of collagen [1, 2]. OMs most commonly occur in the posterior mandible, and the average age of patients is 25 to 30 years old [2]. Some literature states there is no sex predilection [2], while others have found the OM to be up to twice as common in females [3]. Radiographically, the OM can appear as unilocular or multilocular radiolucencies, and has well-known patterns including “soap bubble”, “tennis racket”, and “honeycomb” [3]. The “sunray” or “sunburst” radiographic appearance of OMs has been infrequently reported in the English language literature with only 20 cases reported to date [4–18]. Although it is rare for the OM, a benign tumor, to display a sunray or sunburst pattern it is a classic presentation for some malignancies such as osteosarcomas [1, 19]. The objective of this paper is to report a case of an OM displaying a radiographic sunburst appearance, provide a review of the literature on this uncommon presentation, and discuss the prognosis and recurrence of this radiographic variant.

Case Report

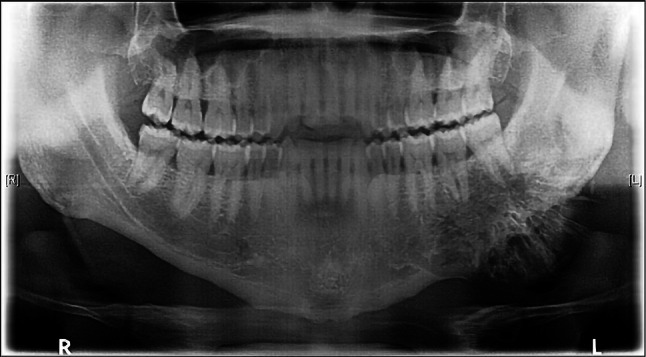

A 34-year-old male presented to the oral surgery department at Mount Sinai Hospital with mild expansion of the left posterior mandible. He stated that it had been increasing in size for about 12 years. No infection was present, and the patient denied any pain or changes in his occlusion. Intraorally, the mandibular expansion was noted to extend from the left mandibular angle to the left first molar area. A panoramic radiograph displayed a sunburst appearance of the left posterior mandible (Fig. 1). Oral surgeons included osteosarcoma in their differential diagnosis due to this distinct radiographic appearance.

Fig. 1.

Pre-operative panoramic radiograph displays a distinctive sunburst appearance of the left posterior mandible, encompassing the premolar and molar region

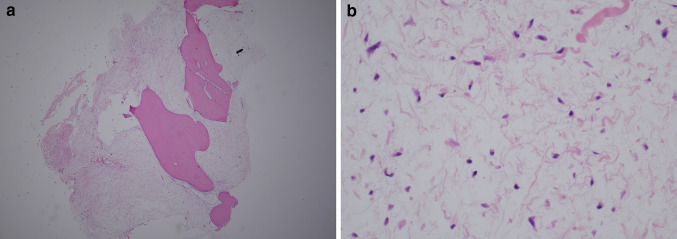

An incisional biopsy was performed and evaluated microscopically. Decalcified sections showed that the tumor consisted of cells with uniform, basophilic, slender to triangular-shaped nuclei with delicate cytoplasmic processes (Fig. 2a, b). The tumor was admixed with viable bone fragments and foci of fibrosis. The incisional biopsy was given a diagnosis of OM.

Fig. 2.

Incisonal biopsy of specimen. a Low power H&E shows tumor admixed with bone fragments. (H&E × 2). b High power H&E displays tumor cells that consist of basophilic, stellate and spindle shaped nuclei within a loose, myxoid stroma (H&E × 40)

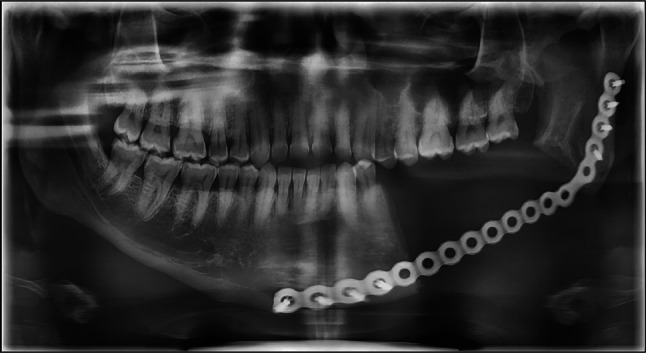

The patient returned for a computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 3a, b) followed by a segmental resection of the mandible. The resection was done with 1.0 cm margins, encompassing the left body of the mandible to the left angle of mandible, including the removal of teeth #17–20. Reconstruction of the mandible with a transosteal bone plate was performed with no complications (Fig. 4). Oral surgeons made plans for future final reconstruction with iliac crest graft and dental implants.

Fig. 3.

Computed tomography scan. a Anteroposterior and b lateral views show an expansile mass with a sunburst appearance within the left mandibular region

Fig. 4.

Post-operative panoramic radiograph of the mandible reconstructed with a transosteal bone plate. Radiograph shows the resection of mandible involved the removal of teeth #17–20 extending to the left angle of the mandible

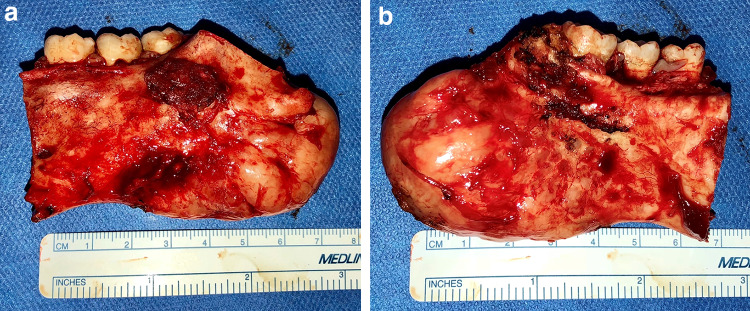

Gross examination of the resection specimen revealed a 5.0 × 2.8 × 2.2 cm tan-white, bony mass protruding from the posterior and inferior aspect of the mandible (Fig. 5a, b). The mass had ill-defined borders and was interspersed with white gelatinous tissue. Histological examination of the specimen revealed identical findings to the incisional biopsy, confirming the diagnosis of OM (Fig. 6a, b).

Fig. 5.

Gross specimen. a Buccal and b lingual views show an ill-defined bordered mass protruding from the posterior and inferior aspect of the mandible

Fig. 6.

Excisional biopsy of specimen was identical to the findings of the incisional biopsy. a Low (H&E × 2) and b high power (H&E × 40) views

The patient returned for a 3-week follow-up appointment but missed the subsequent follow-up appointment a month later. Ultimately, the patient never returned for further treatment.

Discussion and Review of the Literature

A study by Zhang et al. divides the various radiographic appearances of OMs into six types. The first type (type I) is a unilocular radiolucency. Multilocular radiolucencies creating a “honeycomb”, “soap bubble”, or “tennis racket” appearance are categorized as type II. Type III includes lesions that involve local alveolar bone. Type IV lesions consist of those involving the maxillary sinus. Lesions that cause osteolytic destruction and “moth-eaten” margins are categorized as type V. Lastly, the sunray appearance is classified as type VI [10]. Other authors use the terms “hairbrush” and “fishbone” in addition to “sunburst” when describing this radiographic pattern in their case of OM [14]. “Sunray”, “sunburst”, and “hair-on-end” are all synonymous radiographic terms used to describe thin, straight spicules of bone caused by a periosteal bone reaction [1]. This spiculated pattern is most characteristic of very aggressive and fast-growing tumors [20] including osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, central hemangioma, and metastatic prostate and breast lesions [1, 19, 21]. Though it has not been described in OMs, it is also of importance to note the laminated or “onion skin” radiographic appearance that is usually in response to inflammation, termed proliferative periostitis [2]. In this instance, the formation of periosteal new bone is displayed as a single radiopaque line or a series of radiopaque lines parallel to the surface of the cortical bone [1]. Fortunately, histological evaluation can confirm the diagnosis of an OM when the radiographic patterns are misleading.

OMs have been examined with many different imaging modalities. These include conventional radiography (CR) such as panoramic, occlusal, and periapical radiographs; cone beam computed tomography/computed tomography (CBCT/CT); and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In some studies, it appears that the sunray/sunburst radiographic pattern is more likely to be seen with CBCT/CT versus others [8, 15]. However, there are 15 cases in the literature in which the sunray/sunburst pattern of OMs was indeed seen on CR [5–7, 9–14, 17, 18]. It is possible that some of the features that CBCT has in comparison to CR may make it more likely to display a spiculated pattern. For instance, in contrast to CR, CBCT displays a lesion’s fine internal structures [16], the extent of the lesion, and involvement of adjacent anatomic structures more precisely [20]. However, the best method of displaying this rare pattern cannot be determined based on the varying imaging modalities used in the previous cases in the literature.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, 20 cases of radiographic sunray/sunburst OMs have been published in the English language literature [4–18]. Table 1 presents a review of these 20 cases. Based on data from these cases and our additional case, approximately 15 of 18 known sites were in the mandible [4–6, 9–18]. Patient ages ranged from 17–35 with an average age of 26. Out of 15 cases with known sex, there were 7 males and 8 females [4–18]. The demographics and locations of these cases are similar to OMs that present more classically [2, 3]. The sites of 3 tumors, the ages of 5 patients, and the sex of 6 patients could not be determined from the review of the literature [5, 10, 16].

Table 1.

Cases of sunray/sunburst odontogenic myxoma

| Author | Review of 20 cases reported in the literature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases | Sex | Age | Site | Imaging | Treatment | Follow-up | |

| Large et al. [4] | 1 | M | 35 | MD | * | Resection | 3y NR |

| Schmidseder et al. [5] | 1 | * | 34 | POST MD | Panoramic | Resection | 7y NR |

| Chuchurru et al. [6] | 1 | F | 20 | MD | Occlusal | Resection | 1.5y NR |

| Peltola et al. [7] | 1 | F | 31 | MX Sinus | Panoramic | * | * |

| MacDonald-Jankowski et al. [8] | 1 | M | 17 | MX | CT | * | * |

| Li et al. [9] | 1 | F | 22 | POST MD | Panoramic | Block resection | 7y NR |

| Zhang et al. [10] | 5 | M, M*** | 28, 27*** | MD, MD*** | Conventional radiography (not specified) | ***** | ***** |

| Sara Thomas et al. [11] | 1 | F | 27 | POST MD | Lateral oblique | Segmental resection | 2y NR |

| Kidwai et al. [12] | 1 | M | 28 | POST MD | Panoramic & CBCT | Surgical excision | NR |

| Goel et al. [13] | 1 | F | 18 | POST MD | Panoramic & CT | Hemimandibulectomy | 1y NR |

| Varun et al. [14] | 1 | F | 35 | MD | Occlusal | Surgical resection | * |

| Dabbaghi et al. [15] | 1 | F | 27 | POST MD | CBCT | Block resection | 2y NR |

| Wang et al. [16] | 2 | ** | ** | MX/Sinus, ANT MD | CBCT, CBCT |

NR NR |

** |

| Garg et al. [17] | 1 | M | 22 | MD | Panoramic | * | * |

| Das et al. [18] | 1 | F | 17 | POST MD | Panoramic | Excision of lesion | 3 m NR |

NR no evidence of recurrence

*Not available

Treatment of OMs depends on the size of the lesion. Smaller lesions may only need curettage. Larger lesions necessitate resection as they tend to infiltrate surrounding bone. This is due to the loose myxoid composition and lack of encapsulation of OMs [2]. The high permeability of the tumor into neighboring tissues makes the method of removal a crucial determinant of recurrence. Typically, OMs have recurrence rates of around 25% [2, 3]. Recurrence following incomplete removal would usually occur within 2 years but can occur much later [3]. For the nine cases in the literature that provided length of follow-up, the follow-up period ranged from 3 to 84 months (7 years) with an average of 36 months (3 years), and all with no recurrences reported [4–6, 9, 11–13, 15, 18]. 11 of the cases did not report any follow up data [7, 8, 10, 14, 16, 17]. Based on this limited number of cases, there does not appear to be an increased rate of recurrence associated with the sunray/sunburst radiographic appearance compared to more traditional radiographic presentations.

Conclusions

Many authors have previously presented evidence that OMs can have varying radiographic appearances [7, 10]. This paper serves to further the awareness of the prevalence and prognosis of the sunburst radiographic pattern of OMs. The sunray or sunburst presentation of OMs is not the most common presentation; however, it is necessary for clinicians and pathologists to be cognizant of it. Very often, the sunray or sunburst appearance has been associated with a malignant process and prompts a differential diagnosis that gravitates toward malignant entities [1, 19]. Even in the case reported here, a clinical diagnosis of osteosarcoma was considered before histologic evaluation. Therefore, there is value in the awareness that the OM, a benign lesion, can have this same appearance. It is important that the sunray/sunburst pattern become a more recognized radiographic presentation of OMs to aid in the diagnostic process. Ultimately, despite the fact that the rare radiographic sunray/sunburst appearance mimics that of a malignant process, histologic evaluation reveals characteristic findings of an OM, and there does not appear to be an increased rate of recurrence. However, studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow up periods would help to further confirm whether prognosis could potentially be affected.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

No funding obtained.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declares that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jamie A. White, Email: Jamie.White@mountsinai.org

Naomi Ramer, Email: Naomi.Ramer@mountsinai.org.

Todd R. Wentland, Email: Todd.Wentland.omfs@gmail.com

Molly Cohen, Email: Molly.D.Cohen@gmail.com.

References

- 1.White SC, Pharoah M. Oral radiology: principles and interpretation. 7. Amsterdam: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Chi AC. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. 4. Amsterdam: Elsevier Inc.; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Naggar AK, Chan JK, Rubin Grandis J, Takata T, Slootweg PJ. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. 4. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Large ND, Niebel HH, Fredricks WH. Myxoma of the jaws: report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1960;13(12):1462–1468. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(60)90236-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidseder R, Groddeck A, Scheunemann H. Diagnostic and therapeutic problems of myxomas (myxofibromas) of the jaws. J Maxillofac Surg. 1978;6:281–286. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0503(78)80107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chuchurru JA, Luberti R, Cornicelli JC, Dominguez FV. Myxoma of the mandible with unusual radiographic appearance. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;43(12):987–990. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(85)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peltola J, Magnusson B, Happonen RP, Borrman H. Odontogenic myxoma—a radiographic study of 21 tumours. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;32(5):298–302. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(94)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacDonald-Jankowski DS, Yeung RWK, Li T, Lee KM. Computed tomography of odontogenic myxoma. Clin Radiol. 2004;59(3):281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li TJ, Sun LS, Luo HY (2006) Odontogenic myxoma: a clinicopathologic study of 25 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med 130(12):179sssss9–1806. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Zhang J, Wang H, He X, Niu Y, Li X. Radiographic examination of 41 cases of odontogenic myxomas on the basis of conventional radiographs. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2007;36(3):160–167. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/38484807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas PS, Babu GS, Mishra C, Anusha RL, Shetty S. Odontogenic myxoma: report of two cases with review of literature. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2011;23(2):143–146. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10011-1115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kidwai S, Mohan RP, Wadhwan V, Kamarthi N, Goel S, Gupta S. Sunburst appearance in odontogenic myxoma of mandible: a radiological diagnostic challenge. J Oral Maxillofac Radiol. 2016;4(1):18. doi: 10.4103/2321-3841.177065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goel S, Goel M, Dinkar AD (2016) Odontogenic myxoma of mandible with unusual (sunburst) appearance: a rare case report. J Clin Diagn Res 10(5):ZJ05 10.7860/JCDR/2016/20123.7812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Varun A, Ramachandran S, Rajasekharan A, Balan A. Odontogenic myxoma: an archetypal presentation of a rare entity. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2016;28(4):465–469. doi: 10.4103/jiaomr.JIAOMR_25_16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dabbaghi A, Nikkerdar N, Bayati S, Golshah A. Rare appearance of an odontogenic myxoma in cone-beam computed tomography: a case report. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospect. 2016;10(1):65–68. doi: 10.15171/joddd.2016.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang K, Guo W, You M, Liu L, Tang B, Zheng G. Characteristic features of the odontogenic myxoma on cone beam computed tomography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2017;46(2):20160232. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20160232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garg K, Sachdev R, Singh SK, Mehrotra V. Oral medicine and radiology: case report on sunburst appearing odontogenic myxoma of mandible: basic approach. Clin Dent. 2018;12(7):21–24. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Das S, Mazumdar A. Odontogenic myxoma: A case report and review. Indian J Case Reports. 2019. https://atharvapub.net/IJCR/article/view/1343/1028. Accessed February 26 2019

- 19.Larheim TA, Westesson PLA. Maxillofacial imaging. 2. Berlin: Springer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scarfe WC, Angelopoulos C. Maxillofacial cone beam computed tomography. New York: Springer International Publishing; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varghese G, Singh S, Sreela L. A rare case of breast carcinoma metastasis to mandible and vertebrae. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2014;5(2):184. doi: 10.4103/0975-5950.154832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]