Abstract

Primary intraoral angiosarcoma is an exceptionally rare malignancy of vascular origin which can be challenging to diagnose due to microscopic and immunohistochemical variability. A histopathologically challenging case of primary intraoral angiosarcoma, occurring in a pediatric patient is presented. A comprehensive review of the literature reveals that primary intraoral angiosarcomas occur with nearly equal frequency in males and females, affect the gingiva and the tongue most commonly and are treated primarily with surgery. As with angiosarcoma in other sites, primary intraoral angiosarcoma behaves aggressively with the majority of patients succumbing to their disease.

Keywords: Angiosarcoma, Oral, Tongue

Introduction

Angiosarcoma is a rare vascular malignancy, accounting for only 1% of sarcomas [1]. Skin is the most commonly affected site; however, angiosarcomas are known to affect breast, liver, spleen, bone and rarely the deep soft tissue [2]. Amongst head and neck angiosarcomas, oral angiosarcomas are exceedingly uncommon, representing only 2% of all angiosarcomas, and both primary and metastatic oral angiosarcomas are known to occur [3]. Reports of primary oral angiosarcoma are limited, with most cases representing single case reports or small case series. A series of 29 cases, including both primary and metastatic lesions, reported by Fanburg-Smith et al., appears to be the largest collection of oral and salivary gland angiosarcomas reported in the literature to date [4].

By definition, angiosarcomas are vasoformative, but are known to show variable histopathology, including epithelioid, spindled and solid forms [5]. Papillary growth may also be seen [4]. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is used to confirm the vascular phenotype. Angiosarcomas typically express vascular markers including CD34, CD31, von Willebrand factor (vWF), Fli1, ERG and can express D2–40 [6–8]. Due to variable rates of sensitivity and specificity, a panel of vascular markers is typically advised in the assessment of a potential angiosarcoma [9]. CD 31 is highly sensitive, shows good specificity, and is considered by many to be the gold standard for diagnosis of angiosarcoma [6, 10, 11]. However, CD31 can be expressed uncommonly in other malignancies, including carcinomas, and is positive most in histiocytic sarcomas [10, 12, 13]. Further, granular positivity in intratumoral macrophages is recognized as a substantial diagnostic pitfall in the diagnosis of vascular neoplasms [14]. Recently, ERG has also been shown to be a sensitive and specific endothelial marker, which is strongly expressed in the majority of angiosarcomas, regardless of differentiation [11].

Morphologically, the spindled type of angiosarcoma is the most common intraoral and salivary gland pattern reported; however, up to 33% of primary oral angiosarcomas in a large case series demonstrated an epithelioid pattern [4]. Given the potential of epithelioid angiosarcomas to express keratins [15] and to mimic poorly differentiated carcinoma, consideration of this entity in the differential diagnosis of a spindled or epithelioid oral malignancy is important, but may fall under the radar of many pathologists.

Angiosarcomas are aggressive neoplasms and are generally associated with a poor prognosis [16–18]. Nevertheless, there is limited evidence from the literature that suggests that primary oral angiosarcomas may have more favourable biologic behaviour when compared to angiosarcomas of other sites [4].

Case Report

An 18-year-old male presented with a 5-month history of a deep, 1.0 × 2.5 cm, painful, non-healing ulcer of the posterior dorsal tongue in the area of the foramen cecum. Previously, he underwent an incisional biopsy at another institution which was reported as granulation tissue. A subsequent incisional biopsy, demonstrated an infiltrative spindled to epithelioid malignancy (Fig. 1). In areas where epithelioid cells were present, abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and occasional macronucleoli were seen. In many areas, the tumour cells were spindled and demonstrated a fascicular pattern of growth, with a subset of cells showing a myogenic appearance. Cellular pleomorphism was most pronounced in the superficial aspects of the lesion. The vascular nature of the lesion was not prominent; however, slit-like vascular spaces were seen superficially. The malignant cells showed diffuse membranous positivity for CD31 and diffuse nuclear positivity for ERG (Fig. 2). Additionally, AE1–AE3 and vimentin were positive. CD34 and HHV8 were negative. Molecular studies were performed to exclude the possibility of hemangioendothelioma. Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) failed to detect a TFE3 gene rearrangement, and RT-PCR failed to detect the WWTR1-CAMTA1 fusion. Subsequent testing was also done to exclude the possibility of pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, with no rearrangements of FOSB or SERPINE1 detected by break-apart FISH. The patient underwent an excision 1 month following diagnosis and was found to have close but negative margins on the surgical specimen. Post-operative radiation treatment was planned; however, follow-up information is not available. The clinicopathologic features of this case are summarized in Table 1.

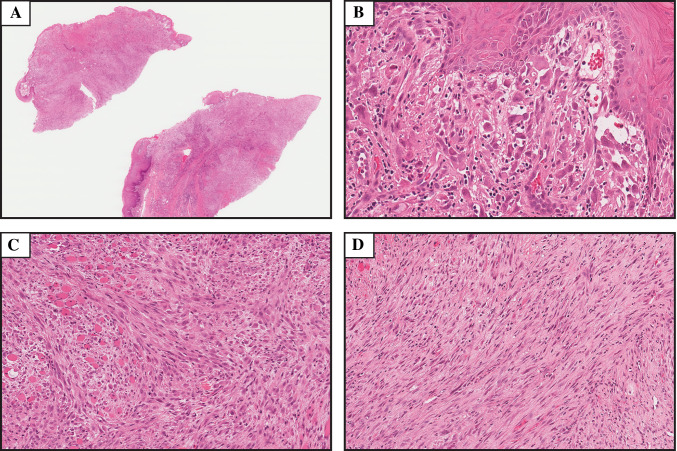

Fig. 1.

Hematoxylin and eosin stained sections depicting the microscopic features of the case presented. a Low power image showing an infiltrative, cellular neoplasm (magnification × 1). b Cellular pleomorphism was most prominent superficially, and cells in this area were epithelioid. Vascular differentiation was not conspicuous, but primitive vasculature formation can be seen here (magnification × 25). c In many areas tumor cells showed a spindled morphology with a myogenic appearance (magnification × 14). A fascicular arrangement was also present in much of the tumor (magnification × 14)

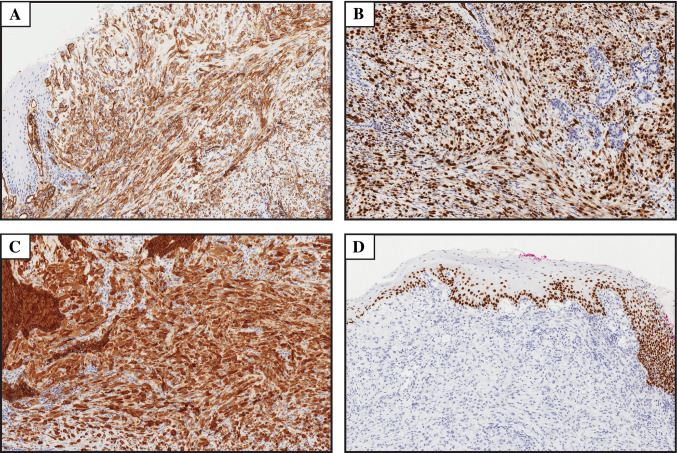

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical features of the case presented. a–c Diffuse immunoreactivity for CD31, ERG and cytokeratin AE1–AE3, respectively (magnification × 10). d The tumor was negative for p63 (magnification × 8)

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic features of the case presented

| Age | Sex | Site | Clinical | Histomorphology and immunohistochemistry | Treatment and vital status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | M | Dorsal tongue | 5-month history of 1.0 × 2.5 cm deep ulcer |

Infiltrative spindled to epithelioid malignancy with areas of fascicular growth Pos: CD31, ERG, CK AE1/AE3, vimentin, SMA (focal), EMA (focal) Neg: CD34, HHV8, desmin, myogenin, S100, p63, HMB45, h-caldesmon INI-1 expression retained |

Surgery UK |

Pos positive, UK unknown, Neg negative

Review of the Literature

A comprehensive review of the English language literature was conducted, using keyword (oral, angiosarcoma, head and neck) and MeSH terms (hemangiosarcoma, mouth, maxilla and mandible). Cases were excluded from our analysis if they did not report immunohistochemical and/or electron microscopy evidence of vascular differentiation. Due to variability in the sensitivity and specificity of markers used to assess vascular lineage, [9] cases described before CD 31 became commercially available were excluded. A total of 39 cases from 19 reports [4, 17–34] were identified, including the new case reported herein. The clinical, microscopic, treatment and vital status data of the previously reported cases are summarized in Table 2. The median age of affected patients is 63 years, with a wide age range (6–83 years). Five cases occurred in pediatric patients aged 18 years or younger. Of the 39 cases evaluated, 19 cases occurred in females and 20 cases occurred in males. The most common site of involvement of primary intraoral angiosarcoma reported was the gingiva (12), followed by the tongue (11). In order of decreasing frequency, other sites of involvement included: lip (5), soft palate/retromolar trigone (4), hard palate (3) buccal mucosa (2), mandible (1), floor of mouth (1).

Table 2.

Clinicopathologic features, treatment and vital status of reported cases of primary intraoral angiosarcoma

| Author | Age | Sex | Site | Clinical | Histomorphology and immunohistochemistry | Treatment and vital status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loudon et al. [19] | 68 | F | Right FOM | Soft tissue mass, bluish, focal ulceration, recent rapid enlargement, ill defined bony involvement | Pos: FVIIIa (patchy/weak), CD31, CK (AE1/AE3, Cam5.2), vimentin |

Resection DOD 8 mos |

| Favia et al. [17] | 65 | F | Retromolar trigone | Bluish, painful, 5.5 × 4.4 × 4 cm |

Abortive vessels and spindle cells Pos: FVIIIa, CD31, CD34 |

RT + CMT DOD 3 mos |

| 70 | M | Hard palate |

Dark red, expanding mass 4 × 3 × 3 cm |

Spindle cells, intercellular haemorrhage, slit-like spaces Pos: FVIIIa, CD31, CD34 |

Resection + CMT DOD 3 months |

|

| 74 | F | Hard palate |

Cherry red, expanding mass 5 × 5 × 3 cm |

Epithelioid angiosarcoma with rare slit-like spaces Pos: CD31 Neg: FVIIIa, CD34 |

Partial maxillectomy + CMT Died 4 months |

|

| 82 | F | Alveolar ridge (31–36) |

Purplish Red, expanding mass 6 × 5 × 3.5 cm |

Abortive vessels and pleomorphic spindle cells Pos: CD31, CD34 Neg: FVIIIa |

RT + CMT DOD 6 mos |

|

| Fanburg-Smith et al. [4] | 30 | F | Tongue | UK | Epithelioid and solid | UK |

| 62 | M | Tongue | UK | Epithelioid and focal | UK | |

| 24 | F | Tongue | UK | Solid |

11 years NED UK |

|

| 30 | F | Tongue | UK | Solid |

13 years NED UK |

|

| 68 | M | Tongue | UK | Solid |

DOD 9 years UK |

|

| 6 | F | Tongue | UK | Solid | UK | |

| 30 | M | Tongue | UK | Solid (focal) |

4 years NED UK |

|

| 65 | M | Tongue | UK | Solid |

DOD 12 mos UK |

|

| 83 | F | Tongue | UK | Vasoformative |

1 year NED UK |

|

| 67 | F | Lip | UK | Epithelioid and solid |

13 years NED UK |

|

| 52 | F | Lip | UK | Epithelioid and solid |

16 years NED UK |

|

| 68 | M | Lip | UK | Solid | UK | |

| 18 | M | Lip | UK | Papillary |

14 years NED UK |

|

| 16 | M | Soft palate | UK | Very focal, epithelioid papillary, and solid | UK | |

| 82 | M | Hard palate | UK | Solid | UK | |

| Florescu et al. [20] | 70 | M | Alveolar crest of mandible | Poorly defined nodular purple mass, 4 cm |

Epithelioid Pos: CD 31, AE1/AE3 (focal) Neg: Vimentin |

UK |

| Driemel et al. [21] | 63 | M | Alveolar ridge | Polypoid, superficially ulcerated mass, 1.5 × 1 × 1 cm with mets to pleura and ileum | Pos: CD31, CD34, FVIIIa, Fli-1, CK (subset) | DOD 2 mos |

| Arribas-Garcia et al. [22] | 15 | M | Left paracomissural mucosa of lower lip | Rounded, well-defined tumoral lesion of red-bluish color, 1–1.5 cm diameter |

Irregular anastomosing vascular channels with marked cytological atypia Pos: CD34, CD31 |

Resection NED 2 years |

| Yang et al. [23] | 81 | F | Soft palate | 5–10 cm | Pos: CD31, CK |

Surgery + RT Recurrence, UK |

| Mücke et al. [24] | 76 | M | Multifocal (upper right incisor, first molar and lower right second premolar) | Multifocal ulcerative gingival lesions, history of necrotizing gingivitis (HIV neg). Lymph node mets |

Atypical cells, hemorrhage and well formed vascular channels lined by endothelium Pos: CD 31 Neg: CD34, CD45, CD68, CK18, HMWK, S100, KP-1, MPO, Factor VIIIa |

Resection + RT DOD 6 mos |

| Terada et al. [25] | 54 | F | Left cheek adjacent to the mandibular gingiva | Oral mass, 1 cm |

Solid tumour of atypical spindle and polygonal cells, nuclear hyperchromasia, intracytoplasmic vacuoles and mitoses Pos: Vim, CD34, FVIIIa, CD31 Neg: AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, SMA, EMA, S100, p63 |

Radical resection NED 1 mos |

| Suzuki et al. [26] | 69 | F | Right maxillary gingiva | Bleeding, recent enlargement, large, rounded, well-defined mass, purple to red surface, destruction of tuberosity |

Epithelioid Pos: FVIIIa, CD31 |

RT + CMT Lung metastasis 2 mos DOD 8 mos |

| Sumida et al. [27] | 55 | F | Anterior mandibular gingiva | Well-defined epulis like lesion, soft, white-red, easy bleeding |

Spindled to polygonal Pos: CD31, FVIIIa, SMA, vim Neg: panCK, S100, NSE, CD56 |

Resection NED 4 years |

| Doeuk et al. [28] | 46 | F | Left mandible | History of pain in the left jaw for 6 months, infiltrative bony lesion with IAN extension, no paresthesia |

High grade epithelioid Pos: CD31, CD34 (weak) Neg: AE1/AE3, pan melanoma, CD68 |

Resection NED 18 mos |

| Nagata et al. [18] | 55 | M | Mandibular gingiva | Rapidly expanding bluish mass, hemorrhagic and fragile, 2.5 × 2.0 cm |

Epithelioid angiosarcoma with rare slit-like spaces, Grade III Pos: CD34, EMA Neg: AE1/AE3 |

Resection Thoracic vertebral metastasis DOD 3mos |

| 64 | M | Maxillary gingiva | Dark red, hemorrhagic and fragile expanding mass, 4.2 × 2 cm |

Spindle cells, intercellular haemorrhage, slit-like spaces, Grade II Pos: FVIIIa, CD31, CD34, vim Neg: AE1/AE3, S100, SMA |

Resection + CMT Lung mets with lobectomy NED 30mos |

|

| 78 | F | Tongue | Pink, hemorrhagic, painful expanding mass, 6.0 × 5.0 cm |

Abortive vessels and pleomorphic spindle cells, with epithelioid areas Grade III Pos: CD31, vim, AE1/AE3 Neg: FVIIIa, CD34, S100, SMA, desmin |

Resection Lung mets DOD 6 mos |

|

| Fomete et al. [29] | 35 | M | Left cheek oral mucosa | Firm, ulcerated mass, protruding intra-orally, 4 year history, 10 × 7 cm |

Spindled with sheet like growth, anastomosing dilated vasculature, hemorrhage, necrosis Pos: CD31 |

Resection NED 3 months NED |

| Aljadeff et al. [30] | 79 | M | Between left maxillary lateral incisor and canine | Red and ulcerated exophytic growth, 0.9 × 0.6 × 0.3 cm no pain, no paresthesia, no bone involvement |

Large pleomorphic and atypical epithelioid cells Pos: CD31, vim, ERG Neg: CD20, CD30, AE1/AE3, S100, MNF-116 |

Resection and post op RT DOC, 4 mos |

| Hunasgi et al. [31] | 30 | F | Gingiva labial aspect of 31–41 |

Soft, sessile painless growth arising from the labial gingiva, 3 × 3 cm, 2 month history Alveolar crestal and interproximal bone loss |

Spindled to polygonal with anastomosing vascular channels, nucleoli, mitoses, intracytoplasmic vacuoles Pos: FVIIIa, CD31, CD34 |

Surgery, negative margins NED 2 years |

| Chamberland et al. [32] | 83 | M | Gingiva and both palatine tonsils | Painful gingival lesion followed by hematoma of palatine tonsil |

Pos: CD31, CD34, SMA (partial) Neg: HHV-8, BNH9, p63, panCK, CK5/6, EMA |

CMT + RT DOD 4 months |

| Patel et al. [33] | 57 | M | Gingiva and both palatine tonsils | Irritation and fullness in the mouth | Pos: CD31, ERG |

Resection + CMT DOD 7 months |

| Hartanto et al. [34] | 52 | F | Soft palate | Soft and mobile pedunculated oval mass, reddish-blue in color |

Ovoid to spindled Pos: CD31, Factor VIIIa, Fli-1 |

DOD short time |

FOM floor of mouth, Pos positive, DOD died of disease, RT radiation therapy, CMT chemotherapy, Neg negative, NED no evidence of disease, UK unknown, DOC died other cause, CK cytokeratin, Vim vimentin, Mets metastasis

The most commonly reported treatment modality reported in the literature for primary oral angiosarcoma is surgery. Of the cases included which reported treatment, 81% (17/21) patients were treated with surgery. Of these (excluding the present case, as post-surgical treatment information is not available), 45% (9/20) of cases were treated with surgery alone, 15% (3/20) were treated with surgery and radiation therapy (RT) and 20% (4/20) were treated with surgery and chemotherapy (CMT). A small number of patients (20% or 4/20) were treated with RT and CMT only.

Of the cases with available follow-up information, 50% (15/30) patients died of disease (range 2 months to 9 years; mean 13 months), 1 patient died of other causes and 47% (14/30) were alive with no evidence of disease, with mean follow-up reported as 6 years (range, 1 month to 16 years).

Discussion

Primary intraoral angiosarcomas are rare, and in the head and neck region most commonly involve the scalp. A recent analysis of 1250 angiosarcomas of the head and neck, found the tongue to be the second most common, non-cutaneous site for head and neck angiosarcoma after the facial bones, with 14% (11/80) of cases occurring in this site [35]. The oral cavity can also be affected by metastatic angiosarcoma and a large series of intraoral and salivary gland angiosarcomas reported 7 metastatic lesions, of which 5 arose from a skin primary in the head and neck [4].

Primary intraoral angiosarcoma most commonly affects older individuals, but exceptionally may affect pediatric patients. The peak age incidence for primary intraoral angiosarcoma is similar to that reported for soft tissue angiosarcomas, with most cases occurring in the 7th decade [15], and is slightly younger than the peak incidence from all head and neck subsites [35]. In pediatric patients, angiosarcoma is exceedingly rare, and most occur in the heart/pericardium [36].

In the deep soft tissue and bone, angiosarcomas more commonly affect males than females [15]. Of the cases reviewed here, an nearly equal distribution between males and females was noted, with a marginally increased frequency in males; however, when only pediatric patients are considered, a stronger male predominance is evident (80%).

The clinical appearance of intraoral angiosarcomas reported in the literature is variable, with many reports describing expansile masses that are blue/red/purple in appearance, with or without ulceration [17, 33]. Some lesions present with bleeding, and most are painless. Ill-defined bony destruction is common in lesions with primary intraosseous presentation, or those invading bone secondarily [19, 33]. The clinical differential diagnosis encompasses several benign and malignant vascular and pigmented lesions, including: pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, melanoma, carcinoma and metastatic disease [4, 18, 19].

Angiosarcoma can be a histologically challenging neoplasm to diagnose, particularly if vasoformation is not a prominent feature. In general, angiosarcomas show variable histomorphology, ranging from well-developed anastomosing vascular channels lined by atypical endothelial cells, to solid sheets of epithelioid or spindled cells. Hemorrhage and necrosis are common [37]. With respect to oral lesions, diagnostic difficulty may be further compounded by the relatively common occurrence of the epithelioid subtype in this site [4, 18, 20, 26, 28, 30]. Epithelioid angiosarcomas are more commonly reported in the deep soft tissue and viscera, and occur less frequently in the skin [2, 15, 38]. Epithelioid angiosarcomas can be particularly troublesome as up to 30% may demonstrate cytokeratin reactivity [1, 4] which can lead to potential misdiagnosis as a poorly differentiated carcinoma. Of the cases included in this review, including our case, 13 reported the presence of epithelioid features, whether focal or widespread. However, only 3 cases with epithelioid features also reported the presence of cytokeratin positivity [18, 20]. Fanburg-Smith et al. reported 5 cases in their series with epithelioid features; however, cytokeratin staining was not performed. The case we present was unusual, as this case did not show a predominant epithelioid phenotype, but strongly expressed cytokeratins. It is known that cytokeratin reactivity is not exclusively seen in the epithelioid type of angiosarcoma; however, is thought to occur more frequently when epithelioid features are present [15]. Expression of p63 has also been reported in malignant vascular tumours, including angiosarcoma. Although expression is typically seen in a small subset of nuclei, Kallen et al., reported one case of epithelioid angiosarcoma with p63 positivity in 75% of cells [39].

Of the cases included in this review, 11 reported a predominant or partially spindled morphology [17, 18, 25, 27, 31, 29, 34]. For tumours showing a spindled phenotype, spindle cell carcinoma must be considered in the differential diagnosis. The diagnosis of spindle cell carcinoma depends on confirmation of the epithelial phenotype through demonstration of a typical carcinoma component (in situ or invasive), or immunohistochemical positivity for epithelial markers [40, 41]. In our case, which was strongly positive for cytokeratin, lack of expression of p63 was helpful in excluding spindle cell carcinoma. However, it is known that spindle cell carcinomas may show an absence of epithelial markers [40], or may show only focal or patchy staining, suggesting that tumours that are non-homogeneous and small or poorly oriented biopsies can lead to diagnostic difficulty. To complicate things further, spindle cell carcinomas can also show pseudoangiomatous change, mimicking angiosarcoma [42]. Although angiosarcomas can express both broad spectrum cytokeratin and p63 staining, to the best of our knowledge, no cases exhibiting this phenomenon have been reported to date. EMA staining in angiosarcoma can also occur, but is uncommon [43].

Due to their morphologic diversity, angiosarcomas can also show histologic and immunohistochemical overlap with several other lesions. For epithelioid neoplasms in particular, the primary differential diagnostic considerations may include epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (EHE), pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (PHE, epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma) and epithelioid sarcoma (ES). EHE and PHE are rare malignancies. Distinction between angiosarcoma and these lesions is important as both EHE and PHE demonstrate more indolent behaviour [9, 38]. EHE demonstrates cords and nests of rounded to spindled endothelial cells, with intracellular lumina (blister cells) being characteristic [9, 37]. Tumours are CD31 and CD34 positive and epithelial markers are expressed in 25–40%. The WWTR1-CAMTA1 fusion is specific for hemangioendothelioma and not found in angiosarcoma [44, 45]. A subset of tumours lacking WWTR1-CAMTA1 show YAP1-TFE3 [46]. PHE most commonly presents as a multinodular proliferation affecting the extremities of young males [47]. Similar to EHE, PHEs are known to express vascular and epithelial markers. PHE characteristically demonstrates a gene fusion involving FOSB. The SERPINE1-FOSB fusion was thought to be characteristic of PHE; however, a recent study has also confirmed the presence of ACTB-FOSB in a subset of cases lacking the SERPINE1-FOSB fusion, which more commonly showed a solitary clinical presentation [48, 49]. The presence of a FOSB rearrangement is helpful in distinguishing pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma from angiosarcoma, and recent investigations have demonstrated good sensitivity of the FOSB antibody in the distinction of PHE from histologic mimics [48, 50, 51]. Classic (distal) epithelioid sarcoma exhibits a multinodular to sheet-like growth pattern. Tumour cells are classically epithelioid, but can also show spindled or rhabdoid morphology. A pseudoangiomatous appearance has been reported due to loss of cellular cohesion and secondary hemorrhage [52]. ES are known to express cytokeratins and EMA, with CD 34 positivity also reported in 50% of cases [53]. Interestingly, ERG positivity has also been demonstrated in ES [11]; however, Stockman and colleagues have helpfully demonstrated that ERG positivity in EHE is significantly more likely when a monoclonal antibody directed at the N-terminus is used [54]. In their study 68% of ES cases tested showed positivity for ERG directed at the N-terminus, while only a single case (3%) showed moderate staining to a C-terminus specific anti-ERG antibody [54]. Furthermore, ES does not express CD31, and most cases of ES will show a loss of INI-1, features which are helpful in distinguishing this lesion from angiosarcoma [53, 54].

A subset of angiosarcomas have shown recurrent alterations involving several genes, including: KDR/PTPRB/PLCG1, MYC/FLT4 and CIC [38, 55]. MYC/FLT4 coamplification is primarily reported in angiosarcomas secondary to radiation or chronic lymphedema [38, 56, 57]. CIC rearrangements have been reported in a small subset of cases demonstrating epithelioid morphology, and have been primarily associated with young adults and cases occurring outside of the breast [55]. The molecular alterations reported are thought to characterize approximately 50% of angiosarcomas [38, 55].

Surgical excision is the most common treatment modality for all angiosarcomas, including those arising intraorally [4, 58], with some patients also receiving radiation treatment or chemotherapy. In general, as a stand-alone treatment, radiation is reported to be less effective than surgery, and chemotherapy is recommended for local disease not amenable to surgery, or metastatic disease [35, 59, 60].

Angiosarcoma is an aggressive neoplasm that is generally associated with a poor prognosis [9]. Head and neck cases of angiosarcoma are no exception, and recently, Lee et al. reported the 5-year overall survival for head and neck angiosarcomas to be 26.5% [35]. Fanburg-Smith et al., suggested that primary oral angiosarcomas may behave more favorably when compared to angiosarcomas of other sites. In their series, only 22% (2/9) patients with a primary oral angiosarcoma died of disease [4]. However, when these results are combined with all of the other reported cases, the majority of patients with primary oral angiosarcoma (50%) succumb to their disease. Interestingly, when site of occurrence is considered, 43% (3/7) of patients with angiosarcoma in the tongue died of disease (DOD) [4, 18], 64% (7/11) cases from the gingiva DOD [17, 18, 21, 24, 26, 32, 33], and no cases from the buccal mucosa or lip died of disease [4, 22, 25, 29]. It should be noted; however, in two cases involving the cheek/buccal mucosa area, the duration of follow-up was extremely short [25, 29]. Due to the limited number of cases published, definitive conclusions about the biological behaviour of primary oral angiosarcomas cannot be made, particularly with respect to how behavior may differ from cutaneous angiosarcomas. Nevertheless, there do appear to be some differences in biologic behaviour based on intraoral site affected, with lesions occurring in the buccal mucosa or lip behaving considerably better than those occurring elsewhere in the oral cavity. Complete data on treatment is not available in all cases with follow-up information, but practically speaking, lesions of the buccal mucosa and lip may be more amenable to complete excision, which may explain why these lesions behave better.

Conclusion

This paper reports a histopathologically challenging case of primary intraoral angiosarcoma. Our case demonstrates some of the potential pitfalls that may arise in the diagnosis of rare intraoral malignancies. Analysis of the literature suggests that the gingiva and tongue are the most common sites of occurrence for primary intraoral angiosarcoma, and just as in other anatomic subsites, primary intraoral angiosarcoma behaves aggressively, with the majority of patients succumbing to their disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Brendan Dickson, Dr. Ilan Weinreb and Dr. Cristina Antonescu for their consultation and the molecular testing of this case.

Funding

None.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Goldbloom JR, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Malignant vascular tumors. Enzinger and Weiss' soft tissue tumours. 6. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher CD, Beham A, Bekir S, Clarke AM, Marley NJ. Epithelioid angiosarcoma of deep soft tissue: a distinctive tumor readily mistaken for an epithelial neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15(10):915–924. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maddox JC, Evans HL. Angiosarcoma of skin and soft tissue: a study of forty-four cases. Cancer. 1981;48(8):1907–1921. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19811015)48:8<1907::aid-cncr2820480832>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fanburg-Smith JC, Furlong MA, Childers EL. Oral and salivary gland angiosarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 29 cases. Mod Pathol. 2003;16(3):263–271. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000056986.08999.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fletcher CD. Vascular tumors: an update with emphasis on the diagnosis of angiosarcoma and borderline vascular neoplasms. Monogr Pathol. 1996;38:181–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeYoung BR, Swanson PE, Argenyi ZB, Ritter JH, Fitzgibbon JF, Stahl DJ, et al. CD31 immunoreactivity in mesenchymal neoplasms of the skin and subcutis: report of 145 cases and review of putative immunohistologic markers of endothelial differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22(3):215–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1995.tb00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folpe AL, Chand EM, Goldblum JR, Weiss SW. Expression of Fli-1, a nuclear transcription factor, distinguishes vascular neoplasms from potential mimics. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(8):1061–1066. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200108000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miettinen M, Lindenmayer AE, Chaubal A. Endothelial cell markers CD31, CD34, and BNH9 antibody to H- and Y-antigens-evaluation of their specificity and sensitivity in the diagnosis of vascular tumors and comparison with von Willebrand factor. Mod Pathol. 1994;7(1):82–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antonescu C. Malignant vascular tumors: an update. Mod Pathol. 2014;27(Suppl 1):S30–S38. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Young BR, Fitzgibbon JF, Sigri KE, Swanson PE. CD31: an immunospecific marker for endothelial differentiation in human neoplasms. Appl Immunohistochem. 1993;1:97–100. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miettinen M, Wang ZF, Paetau A, Tan SH, Dobi A, Srivastava S, et al. ERG transcription factor as an immunohistochemical marker for vascular endothelial tumors and prostatic carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(3):432–441. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318206b67b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hornick JL, Jaffe ES, Fletcher CD. Extranodal histiocytic sarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 14 cases of a rare epithelioid malignancy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(9):1133–1144. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000131541.95394.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKay KM, Doyle LA, Lazar AJ, Hornick JL. Expression of ERG, an Ets family transcription factor, distinguishes cutaneous angiosarcoma from histological mimics. Histopathology. 2012;61(5):989–991. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2012.04286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKenney JK, Weiss SW, Folpe AL. CD31 expression in intratumoral macrophages: a potential diagnostic pitfall. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(9):1167–1173. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200109000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meis-Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG. Angiosarcoma of soft tissue: a study of 80 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22(6):683–697. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199806000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frick WG, McDaniel RK. Angiosarcoma of the tongue: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;46(6):496–498. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(88)90422-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Favia G, Lo Muzio L, Serpico R, Maiorano E. Angiosarcoma of the head and neck with intra-oral presentation: a clinico-pathological study of four cases. Oral Oncol. 2002;38(8):757–762. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(02)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagata M, Yoshitake Y, Nakayama H, Yoshida R, Kawahara K, Nakagawa Y, et al. Angiosarcoma of the oral cavity: a clinicopathological study and a review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;43(8):917–923. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loudon JA, Billy ML, DeYoung BR, Allen CM. Angiosarcoma of the mandible: a case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89(4):471–476. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(00)70127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Florescu M, Simionescu C, Margaritescu C, Georgescu CV. Gingival angiosarcoma: histopathologic and immunohistochemical study. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2005;46(1):57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Driemel O, Muller-Richter UD, Hakim SG, Bauer R, Berndt A, Kleinheinz J, et al. Oral acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma shares clinical and histological features with angiosarcoma. Head Face Med. 2008;4:17. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arribas-Garcia I, Dominguez MF, Alcala-Galiano A, Garcia AF, Valls JC, De Rasche EN. Oral primary angiosarcoma of the lower lip mucosa: report of a case in a 15-year-old boy. Head Neck. 2008;30(10):1384–1388. doi: 10.1002/hed.20773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang XJ, Zheng JW, Zhou Q, Ye WM, Wang YA, Zhu HG, et al. Angiosarcomas of the head and neck: a clinico-immunohistochemical study of 8 consecutive patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39(6):568–572. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mucke T, Deppe H, Wolff KD, Kesting MR. Gingival angiosarcoma mimicking necrotizing gingivitis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39(8):827–830. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terada T. Angiosarcoma of the oral cavity. Head Neck Pathol. 2011;5(1):67–70. doi: 10.1007/s12105-010-0211-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki G, Ogo E, Tanoue R, Tanaka N, Watanabe Y, Abe T, et al. Primary gingival angiosarcoma successfully treated by radiotherapy with concurrent intra-arterial chemotherapy. Int J Clin Oncol. 2011;16(4):439–443. doi: 10.1007/s10147-010-0145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sumida T, Murase R, Fujita Y, Ishikawa A, Hamakawa H. Epulis-like gingival angiosarcoma of the mandible: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5(8):830–833. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doeuk C, McNamara Z, Taheri T, Batstone MD. Primary angiosarcoma of the mandible: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72(12):2499.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fomete B, Samaila M, Edaigbini S, Agbara R, Okeke UA. Primary oral soft tissue angiosarcoma of the cheek: a case report and literature review. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;41(5):273–277. doi: 10.5125/jkaoms.2015.41.5.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aljadeff L, Fisher CA, Wolf SL, Byrd KM, Curtis W, Ward BB, et al. Red exophytic mass of the maxillary anterior gingiva. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122(4):379–384. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunasgi S, Koneru A, Vanishree M, Manvikar V. Angiosarcoma of anterior mandibular gingiva showing recurrence: a case report with immunohistochemistry. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(7):1–4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/18497.8080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chamberland F, Maurina T, Degano-Valmary S, Spicarolen T, Chaigneau L. Angiosarcoma: a case report of gingival disease with both palatine tonsils localization. Rare Tumors. 2016;8(3):5907. doi: 10.4081/rt.2016.5907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel PB, Kuan EC, Peng KA, Yoo F, Nelson SD, Abemayor E. Angiosarcoma of the tongue: a case series and literature review. Am J Otolaryngol. 2017;38(4):475–478. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2017.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haranto FK, Lau SH. A case report of angiosarcoma of maxillary gingiva: hisopathology aspects. Sci Dent J. 2018;2:77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee KC, Chuang SK, Philipone EM, Peters SM. Characteristics and prognosis of primary head and neck angiosarcomas: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program (SEER) analysis of 1250 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2019;13(3):378–385. doi: 10.1007/s12105-018-0978-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deyrup AT, Miettinen M, North PE, Khoury JD, Tighiouart M, Spunt SL, et al. Angiosarcomas arising in the viscera and soft tissue of children and young adults: a clinicopathologic study of 15 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(2):264–269. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181875a5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fletcher CD, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 7. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hung YP, Hornick JL. Epithelioid soft tissue tumors: a clinicopathologic and molecular update. AJSP Rev Rep. 2017;22(2):62–74. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kallen ME, Nunes Rosado FG, Gonzalez AL, Sanders ME, Cates JM. Occasional staining for p63 in malignant vascular tumors: a potential diagnostic pitfall. Pathol Oncol Res. 2012;18(1):97–100. doi: 10.1007/s12253-011-9426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bishop JA, Montgomery EA, Westra WH. Use of p40 and p63 immunohistochemistry and human papillomavirus testing as ancillary tools for the recognition of head and neck sarcomatoid carcinoma and its distinction from benign and malignant mesenchymal processes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38(2):257–264. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Batsakis JG, Suarez P. Sarcomatoid carcinomas of the upper aerodigestive tracts. Adv Anat Pathol. 2000;7(5):282–293. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200007050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Banerjee SS, Eyden BP, Wells S, McWilliam LJ, Harris M. Pseudoangiosarcomatous carcinoma: a clinicopathological study of seven cases. Histopathology. 1992;21(1):13–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1992.tb00338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al-Abbadi MA, Almasri NM, Al-Quran S, Wilkinson EJ. Cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen expression in angiosarcomas: an immunohistochemical study of 33 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131(2):288–292. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-288-CAEMAE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Errani C, Zhang L, Sung YS, Hajdu M, Singer S, Maki RG, et al. A novel WWTR1-CAMTA1 gene fusion is a consistent abnormality in epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of different anatomic sites. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011;50(8):644–653. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanas MR, Sboner A, Oliveira AM, Erickson-Johnson MR, Hespelt J, Hanwright PJ, et al. Identification of a disease-defining gene fusion in epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(98):9882. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Antonescu CR, Le Loarer F, Mosquera JM, Sboner A, Zhang L, Chen CL, et al. Novel YAP1-TFE3 fusion defines a distinct subset of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2013;52(8):775–784. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: a distinctive, often multicentric tumor with indolent behavior. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(2):190–201. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ff0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walther C, Tayebwa J, Lilljebjorn H, Magnusson L, Nilsson J, von Steyern FV, et al. A novel SERPINE1-FOSB fusion gene results in transcriptional up-regulation of FOSB in pseudomyogenic haemangioendothelioma. J Pathol. 2014;232(5):534–540. doi: 10.1002/path.4322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Agaram NP, Zhang L, Cotzia P, Antonescu CR. Expanding the spectrum of genetic alterations in pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma with recurrent novel ACTB-FOSB gene fusions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(12):1653–1661. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sugita S, Hirano H, Kikuchi N, Kubo T, Asanuma H, Aoyama T, et al. Diagnostic utility of FOSB immunohistochemistry in pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma and its histological mimics. Diagn Pathol. 2016;11(1):75. doi: 10.1186/s13000-016-0530-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hung YP, Fletcher CD, Hornick JL. FOSB is a useful diagnostic marker for pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41(5):596–606. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaddu S, Wolf I, Horn M, Kerl H. Epithelioid sarcoma with angiomatoid features: report of an unusual case arising in an elderly patient within a burn scar. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(3):324–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hornick JL, Dal Cin P, Fletcher CD. Loss of INI1 expression is characteristic of both conventional and proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(4):542–550. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181882c54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stockman DL, Hornick JL, Deavers MT, Lev DC, Lazar AJ, Wang WL. ERG and FLI1 protein expression in epithelioid sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27(4):496–501. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang SC, Zhang L, Sung YS, Chen CL, Kao YC, Agaram NP, et al. Recurrent CIC gene abnormalities in angiosarcomas: a molecular study of 120 cases with concurrent investigation of PLCG1, KDR, MYC, and FLT4 gene alterations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40(5):645–655. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Manner J, Radlwimmer B, Hohenberger P, Mossinger K, Kuffer S, Sauer C, et al. MYC high level gene amplification is a distinctive feature of angiosarcomas after irradiation or chronic lymphedema. Am J Pathol. 2010;176(1):34–39. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guo T, Zhang L, Chang NE, Singer S, Maki RG, Antonescu CR. Consistent MYC and FLT4 gene amplification in radiation-induced angiosarcoma but not in other radiation-associated atypical vascular lesions. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011;50(1):25–33. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mullins B, Hackman T. Angiosarcoma of the head and neck. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;19(3):191–195. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1547520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guadagnolo BA, Zagars GK, Araujo D, Ravi V, Shellenberger TD, Sturgis EM. Outcomes after definitive treatment for cutaneous angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Head Neck. 2011;33(5):661–667. doi: 10.1002/hed.21513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ishida Y, Otsuka A, Kabashima K. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: update on biology and latest treatment. Curr Opin Oncol. 2018;30(2):107–112. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]