Abstract

A 47-year-old man presented to the otolaryngology service with complaint of 6 months of intermittent globus sensation. He reported constant throat clearing and subjective lowering of his voice. Flexible nasolaryngoscopy revealed a large pedunculated mass originating from the left vocal process of the arytenoid, lying superior to the vocal fold. The patient was treated conservatively with an anti-reflux regiment and speech language therapy for 2 months, however he noted marginal worsening in voice over the proceeding interval with an increasing raspy quality. He underwent suspension microlaryngoscopy with biopsy. Microscopic examination demonstrated mucosal epithelium with surface ulceration and considerable fibrinoid necrosis, a mixed inflammatory infiltrate, and abundant granulation tissue with reactive endothelial cells. The diagnosis of laryngeal contact ulcer was rendered. The patient was treated with KTP (potassium titanyl phosphate) laser ablation and corticosteroid microinjection; he tolerated the procedures well and on follow-up noted reduced cough, improving voice quality and no residual dysphagia.

Keywords: Laryngeal contact ulcer, Contact ulcer, Vocal process granuloma, Laryngeal pyogenic granuloma, Pyogenic granuloma, Larynx

History

A 47-year-old man presented to an otolaryngology practice with complaint of 6 months of intermittent globus sensation. The sensation was worsened with aggressive sneezing which caused a subjective sensation of throat swelling. He reported intermittent aspiration with liquids without difficulties consuming solids. Additionally, he described constant throat clearing without associated postprandial epigastric or retrosternal chest pain, nighttime cough, or brackish taste in the mouth after awakening. There was no noted odynophagia, otalgia, hemoptysis or unexplained weight loss. Acquaintances had reported his voice had lowered, however he denied any subjective vocal changes. Professional demands include giving long briefs and speeches. Additional history includes seasonal allergies managed with as needed antihistamines but no active postnasal drip or rhinorrhea. He had no surgeries or intubations within the last 2 years and no tobacco use for over 10 years, with a proceeding history of four cigars per month for multiple years. Alcohol use was limited to a maximum of four servings per week.

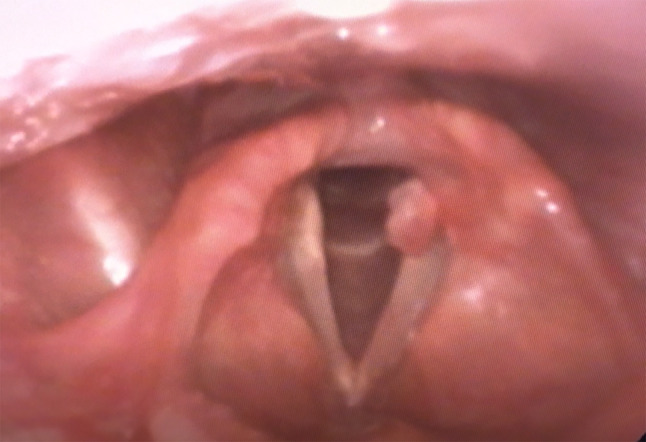

Flexible nasolaryngoscopy revealed normal supraglottic architecture without evidence of pooling secretions in the pyriform sinuses. The subglottis was patent. The true vocal cords demonstrated full abduction and adduction. The left vocal cord had a large pedunculated mass originating from the vocal process of the arytenoid, lying superior to the vocal fold. On stroboscopy the vibration was regular and periodic, mucosal wave propagation was symmetric and amplitude was normal at all pitches and intensities. No evidence of mirrored lesion of the contralateral true vocal cord (Fig. 1). A biopsy was performed.

Fig. 1.

Characteristic presentation of vocal process granuloma. Note pedunculated presentation without mirrored contralateral lesion. Associated erythema of the vocal process. Often presenting with minimal vocal complaints as demonstrated by normal stroboscopy

Diagnosis

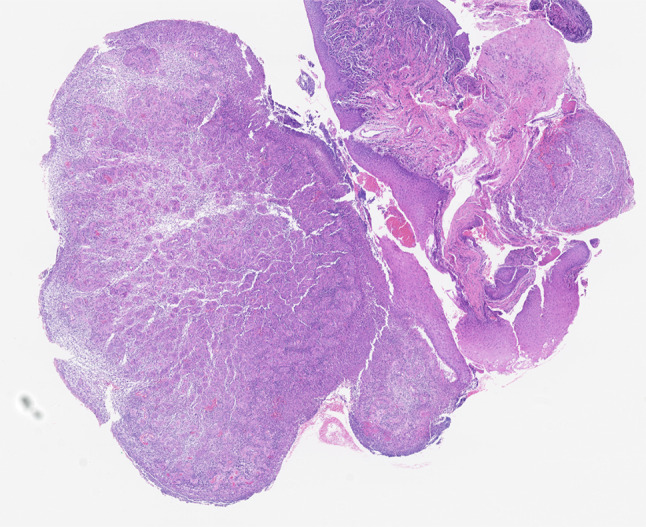

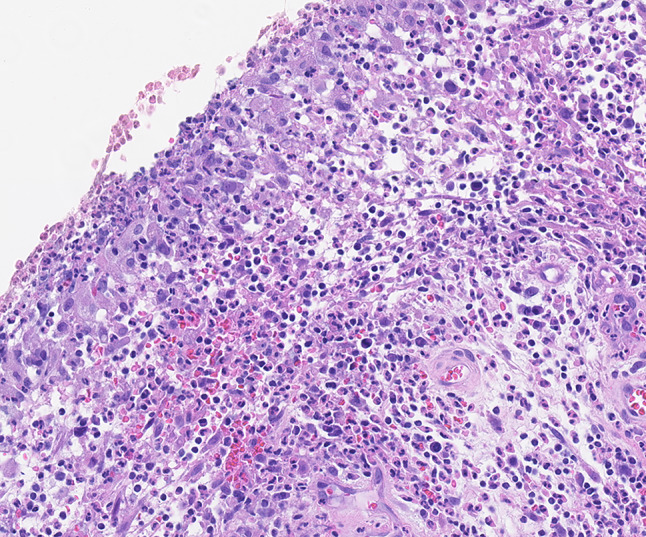

Microscopic examination demonstrated a nodule surfaced by non-keratinizing squamous epithelium with focal surface ulceration (Fig. 2). Superficially, there was considerable fibrinoid necrosis with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate including numerous histiocytes and neutrophils (Fig. 3). Deep to the ulceration was abundant granulation tissue with acute and chronic lymphoplasmacytic inflammation. The endothelial cells within the granulation tissue were reactive and large; additionally, there was considerable red blood cell extravasation (Fig. 4). The characteristic history in conjunction with the classic histology was diagnostic for a laryngeal contact ulcer.

Fig. 2.

Low power H&E image shows non-keratinizing squamous mucosal epithelium with focal surface ulceration

Fig. 3.

Medium power H&E highlights the considerable fibrinoid necrosis

Fig. 4.

High power H&E demonstrates a mixed inflammatory infiltrate including numerous histiocytes and neutrophils. Deep to the ulceration was abundant granulation tissue with acute and chronic lymphoplasmacytic inflammation

Discussion

Laryngeal contact ulcers (also known as laryngeal granulomas or vocal process granulomas) are a benign condition of the vocal cords. These lesions are most commonly caused by vocal cord overuse/abuse, endotracheal intubation, and gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) [1, 2]. There is a slight overall male predominance, however females are more likely to develop the lesions secondary to prolonged and/or ill-fitting endotracheal tubes. Patients typically present with cough, chronic throat clearing, hoarseness, and/or sore throat. If the inciting factor is chronic irritation from GERD, the patient’s chief complain may be heartburn [2, 3].

Laryngoscopy reveals these lesions are frequently located on one or both of the vocal cords. In those cases in which a lesion is found on the contralateral cord, the condition may be referred to as “kissing ulcers.” Laryngeal contact ulcers are typically located on the posterior third of the vocal cords. Clinically, they are commonly ulcerated, however they may also present as a tan-brown to red exophytic or nodular lesion [1, 2, 4]. The foremost consideration in the clinical differential diagnosis is squamous cell carcinoma; this concern may be elevated when the lesion is large and exophytic. The location is important as squamous cell carcinomas uncommonly arise on the posterior vocal cords [2, 4]. Vocal cord nodules and polyps are also a clinical consideration when contact ulcers present in a nodular fashion, however are quickly ruled out on microscopy.

Microscopically, laryngeal contact ulcers show surface ulceration of non-keratinizing squamous mucosal epithelium with considerable fibrinoid necrosis. There is a mixed inflammatory infiltrate including numerous histiocytes with acute and chronic inflammatory cells throughout the fibrin and permeating through the underlying granulation tissue. The granulation tissue is prominent with large, plump reactive appearing endothelial cells lining the newly formed vasculature. Additionally, there can be red blood cell extravasation as well as numerous hemosiderin laden macrophages. As the lesion ages, reepithelization will occur leading to a reactive and hyperplastic appearing squamous mucosa. In late lesions, residual fibrinoid necrosis may still be seen beneath the regenerated mucosa [1, 2, 4]. There is no need for special stains or immunohistochemistry as routine hematoxylin and eosin staining is sufficient for diagnosis.

Histologically, the differential diagnosis principally includes squamous cell carcinoma, an inflammatory process, or vascular lesions. As the lesion progresses, areas of fibrinoid necrosis may be trapped under the newly regenerated reactive mucosa giving the appearance of invasive squamous cell carcinoma. This regenerated mucosa is often irregular which may give the impression of invasions depending on the plane of sectioning [1, 2, 4]. The review of multiple step sections may be helpful in differentiating the reactive process seen in contact ulcers. Importantly, a contact ulcer will lack many of the salient features of squamous cell carcinoma. True invasion should not be identified. Pleomorphism, desmoplastic stroma and atypical mitoses are a seen in squamous cell carcinoma, but not in contact ulcers. Sampling error should be a consideration, additionally. If clinicians have a high degree of suspicion of malignancy, rebiopsy should be considered.

Given the degree of mixed inflammation, infection should always be considered, however clinical history can aid in the distinction. Despite the alternate names for this entity, true granulomas are not a histologic finding and if found should prompt further infectious work-up. If doubt remains, cultures or appropriate special stains may be useful [2, 4].

Lobular capillary hemangioma (pyogenic granulomas), Kaposi sarcoma, or angiosarcoma may also all be considered given the degree of granulation tissue with reactive, plump endothelial cells. Though some authors believe laryngeal contact ulcers and lobular capillary hemangiomas are the same entity and use the names interchangeably, others have argued that laryngeal contact ulcers will not have the classic lobular appearance at low power that pyogenic granulomas demonstrate [4]. Kaposi sarcoma is rare within the larynx and can be ruled out with an HHV8 stain [4]. Finally, it is important to note the endothelial cells are reactive but not atypical in laryngeal contact ulcers, while striking atypia and numerous mitotic figures are commonly seen in angiosarcoma [2, 4].

The treatment of laryngeal contact ulcers is multifactorial, but the principle notion is the removal of the inciting factor. In lesions caused by endotracheal intubation, the inciting factor has already been removed by the time the patient presents to the clinician. Common treatments include anti-reflex medications and speech and language therapy, followed by anti-inflammatories and/or inhaled or oral steroids [3, 5, 6]. Interestingly, it has been described that anti-reflux medication is beneficial for patients with lesions due to endotracheal intubation; these authors postulate that reflux may be a predisposing factor in these patients [6]. Additionally, Botulinum toxin has been shown to be effective in refractory or recurrent lesions [3, 5, 6]. Finally, laser laryngeal techniques and traditional surgical excision may be indicated for large lesions, bilateral lesions, or lesions that fail to resolve with medical therapy [3, 5]. The time frame for resolution following treatment varies depending of the treatment itself; surgical treatment providing the quickest resolution of symptoms with medical therapy take on average between 6 and 8 months [5, 6].

Prognosis is excellent as these are reactive lesions and have no documented malignant potential [2]. Unfortunately, despite the exceptional prognosis, recurrence may be common and challenging to manage. Recurrence rates vary by the etiology of the lesion, however range up to 90% [6]. It is therefore necessary for these patients to have continued follow-up, commonly with laryngoscopy during treatment to ensure complete clinical resolution.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article reflect the results of research conducted by the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the United States Government.

I am a military service member or federal/contracted employee of the United States government. This work was prepared as part of my official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. 105 provides that ‘copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.’ Title 17 U.S.C. 101 defines a U.S. Government work as work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person's official duties.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Thompson LDR. Diagnostically challenging lesions in head and neck pathology. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1997;254:357–366. doi: 10.1007/BF01642550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devany KO, Rinaldo A, Ferlito A. Vocal process granuloma of the larynx—recognition, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Oral Oncol. 2005;41:666–669. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kraimer KL, Husain I. Updated medical and surgical treatment for common benign laryngeal lesions. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 2019;52:745–757. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2019.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson LDR. Larnyx contact ulcer. Ear Nose Throat J. 2005;84(6):340. doi: 10.1177/014556130508400607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karkos PD, George M, Van Der Veen J, Atkinson H, Dwivedi RC, Kin A, Repanos C. Vocal process granulomas: a systemic review of treatment. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2014;123(5):314–320. doi: 10.1177/0003489414525921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rimoli CF, Garcia Martins RH, Cataneo DC, Imamura R, Maria Cataneo AJ. Treatment of post-intubation laryngeal granulomas: systemic review and proportional meta-analysis. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;84(6):781–789. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]