Abstract

Pseduomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (PMH) is a vascular neoplasm of intermediate biological potential first described by Hornick and Fletcher (Am J Surg Pathol 35:190–201, 2011). Despite its initial categorization as a malignant entity, PMH often demonstrates an indolent behavior profile, and thus was classified as a rarely metastasizing endothelial neoplasm in the 2013 WHO Classification of Tumors of Soft Tissue and Bone. It is a tumor primarily of skin and soft tissue, with most reported cases involving the trunk or extremities. To date, only one case of PMH involving the oral cavity has been reported. Herein, we present a case of PMH involving the mandibular gingiva and vestibule of a 33-year-old female and discuss the salient features of this entity.

Keywords: Oral, Pseduomyogenic, Hemangioendothelioma, Vascular tumor, Foreign body

Introduction

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (PMH) is a vascular neoplasm of intermediate biological potential [1]. It was originally considered a fibroma-like variant of an epithelioid sarcoma; however, histomorphologic, immunohistochemical (IHC), and genetic analysis has led to the reclassification of PMH as a unique entity [2]. Distinct features of this neoplasm include a myoid spindle cell morphology, an endothelial IHC staining pattern, and a recurrent translocation (7;19) (q22:q13) [1, 3, 4]. PMH can arise in or involve any tissue layer including epithelium or mucosa, underlying dermis or connective tissue, muscle, or bone [5]. It is most commonly found on the extremities and skin of the trunk where it often presents as a variably painful nodule [1, 6]. A male predilection of approximately 4.6:1 has been reported [1]. Occurrences of PMH involving the head and neck region are exceedingly rare, and with regard to the oral cavity in particular, only one prior case has been described [1, 7]. Herein, we present a case of an oral PMH occurring in a 33-year-old female.

Case Report

A 33-year-old female in excellent overall health was referred to the Columbia University Medical Center Division of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery for evaluation of a painful lesion of the anterior mandibular buccal gingiva. She stated that the area was debrided approximately four months prior by a local periodontist, who removed what was described as a “fishbone” from the site. No tissue was submitted for pathologic evaluation at that time. The surgical site failed to properly heal and the patient was placed on a topical corticosteroid therapy. The patient returned to her periodontist two months after the initial procedure, and a biopsy of the non-healing surgical site was performed. The lesion was diagnosed as “nonspecific inflammation and granulation tissue”. The patient was subsequently referred to our service for further management.

Upon presentation, the patient was not in acute distress. Extraoral examination was within normal limits, with no evidence of trismus, swelling, asymmetry, or palpable lymphadenopathy. On intraoral examination, two distinct slightly raised, firm, red-white lesions were identified on the anterior buccal gingiva and vestibule adjacent to the right mandibular canine and first premolar (teeth #27 and 28). The lesions measured approximately 5 × 4 mm and 4 × 3 mm in size (Fig. 1). Based on the appearance of the lesions and the provided clinical history, a localized foreign body gingivitis was considered, and a re-biopsy of the site was recommended for confirmation of the clinical diagnosis.

Fig. 1.

Clinical photograph demonstrating two distinct red-white lesions (circled) involving the right mandibular facial gingiva and vestibule. The lesions measured approximately 5 × 4 mm and 4 × 3 mm in size and were painful to palpation

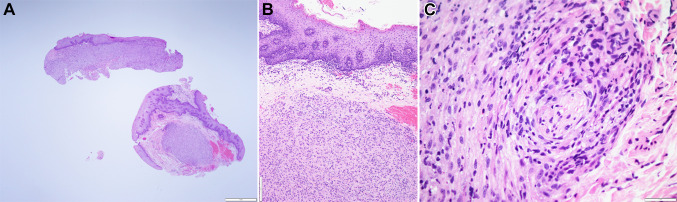

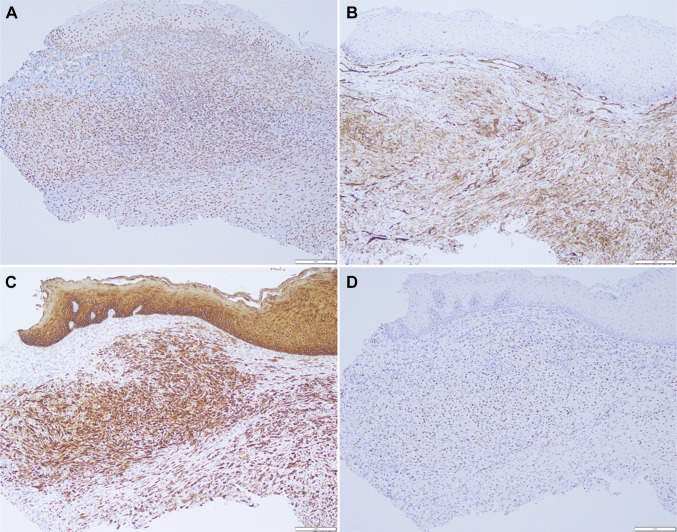

Histologic examination of the specimen revealed surface epithelium overlying fibrous connective tissue. The fibrous connective tissues were infiltrated by plump spindle and epithelioid cells arranged in a loose fascicular and sheet-like pattern within a vascular, fibromyxoid background (Fig. 2a). The lesional cells appear to abut the surface epithelium with ample, albeit not clearly defined, cytoplasm and round to ovoid nuclei with smudged chromatin (Fig. 2b). Mitotic figures were not seen. IHC studies were performed and the lesional cells were diffusely and strongly positive for INI1 (Fig. 3a), CD31 (Fig. 3b), pan cytokeratin (AE1/AE3) (Fig. 3c), CD68, and ERG (Fig. 3d). The lesional cells were negative for S100, CD34, Factor XIIIA, SMA, and desmin. Due to suspicion of PMH, break apart fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) probes for the SERPINE1 and the FOSB loci were used to demonstrate the characteristic SERPINE1-FOSB translocation. Based on the histomorphology, IHC profile, and molecular studies, a diagnosis of PMH was rendered.

Fig. 2.

a Histologic examination revealed a mostly well-defined tumor within the fibrous connective tissue abutting the surface epithelium (H&E, × 20). b Higher power magnification of the tumor in relation to the epithelium (H&E × 100). c On high power magnification, perineural invasion is seen. The tumor consists of plump spindle and epithelioid cells with a rhabdomyoblast-like appearance within a vascular, loose fibromyxoid background intermixed with neutrophils (H&E × 400)

Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemical profiling of the tumor cells showed them to be positive for a INI1, b CD31, c AE1/AE3, and d ERG (× 100)

Following the diagnosis, the patient was sent for additional comprehensive studies prior to definitive treatment. Imaging studies showed no evidence of additional lesions. Definitive surgical management consisted of wide local excision with approximately 1 cm margins. Intraoperative frozen sections were utilized to assess the margin status at the time of resection. The patient is currently one year status post surgical treatment with no evidence of recurrence.

Discussion

PMH is an endothelial neoplasm of intermediate biological potential first reported by Hornick and Fletcher [1]. Although initially described as a malignant entity, it has an indolent behavior profile, and may be more appropriately considered a neoplasm of intermediate biologic potential [1]. Prior to its classification as a distinct entity, PMH was referred to as a “fibroma like variant of epithelioid sarcoma” and “epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma” [2, 8]. Although the current case involved a young female, PMH has a strong predilection for young males, as demonstrated in Hornick and Fletcher’s [1] study of 50 cases which found a gender distribution of almost 5:1 (41 males to 9 females) and a median age at diagnosis of 31 years [1]. Other studies have reported similar age and gender profiles [9]. The most frequent sites of occurrence include the upper and lower extremities, trunk, and genitalia, with the head and neck representing one of the least frequently affected sites [1]. Lesions usually range from 0.5 to 5.5 cm in size and in approximately 50% of cases patients will report pain. More than half of the reported cases of PMH present with multiple nodules affecting the same anatomic region [1].

The clinical differential diagnosis of PMH can vary depending on location. When occurring extraorally, it may include both benign and malignant soft tissue neoplasms, including myofibroma, leiomyoma, benign fibrous histiocytoma, epithelioid sarcoma, and leiomyosarcoma [6]. The intermediate behavior profile of PMH can make it difficult to restrict a clinical differential to solely benign or malignant entities, and in all cases tissue biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis. Due to the scarcity of oral cases, it is difficult to establish a consistent clinical differential diagnosis. In the current case, a localized foreign body reaction was favored given the patient’s history. Given that PMH most often presents as a multinodular process in younger individuals, consideration could also be given to gingival fibromatosis, myofibromatosis, and multiple mucosal neuromas in the setting of Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia 2B Syndrome.

PMH has histologic overlap with many entities and thus histomorphologic differential diagnosis includes epithelioid sarcoma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, epithelioid angiosarcoma, myogenic tumors, and spindle cell/sarcomatoid squamous cell carcinoma. PMH has been described as a primarily spindle cell lesion with an infiltrative pattern. The spindle cells are typically arranged in loose sheets or fascicles and demonstrate vesicular nuclei, variably prominent nucleoli, and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm [7]. In some instances, the lesional cells have a distinctly rhabdomyoblast-like appearance. The tumor cells are often admixed within a vascular fibromyxoid background and variable amounts of neutrophils care commonly seen [7]. Features such as cellular pleomorphism and atypical mitoses are often not observed [7]. Although IHC profiling is required to definitively distinguish an epithelioid sarcoma from PMH, these two entities can also be separated on the basis of histomorphology. Epithelioid sarcoma lacks the plump, myoid appearing spindle cell morphology of PMH as well as its fascicular and sheet-like pattern [10]. The morphology of PMH also differs from that of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (EH). EH presents as epithelioid cells with occasional intracytoplasmic vacuoles arranged in cords in a myxohyaline stroma compared to the solid sheets and fascicles of spindle cells observed in PMH [10]. Epithelioid angiosarcoma (EA) can have histomorphologic overlap with PMH; however, EA has larger epithelioid cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm when compared to PMH. EA also exhibits stromal hemorrhage and high nuclear pleomorphism, whereas PMH is limited to mild atypia. Spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma (scSCC) may also share histologic similarities with PMH. scSCC has a biphasic carcinomomatous and sarcomatoid cellular morphology, in which the normal nesting pattern of conventional squamous cell carcinoma can be lost. Thus a predominantly spindle cell population found in sarcomatoid squamous cell carcinoma can appear similar to the spindle cell population seen in PMH. However, the high grade nuclear features and high mitotic activity can be used to help distinguish this entity from PMH [11]. Lastly, PMH frequently exhibits rhabdomyoblast-like cellular features with eosinophilic cytoplasm, wavy nuclei, and spindle morphology thus myogenic tumors such as leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyoma, rhabdomyosarcoma may be included in the histologic differential.

Although histomorphologic subtleties may be helpful in differentiating PMH from other entities, immunohistochemistry and molecular analysis are required for definitive diagnosis. The tumor cells of PMH consistently stain positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, FLI-1, and INI-1 [7]. The cytokeratin AE1/AE3 stain is theorized to highlight the epithelial differentiation of PMH, but studies have shown that endothelial cells in vascular tumors may stain positive for keratins and thus this could represent innate keratin formation rather than true differentiation [12]. Furthermore, Cytokeratin AE1/AE3 is the only keratin stain that is consistently positive in PMH, whereas other commonly used keratin markers have weak and diffuse reactivity [7]. FLI-1, the nuclear transcription factor that has an association with cellular proliferation and tumorigenesis, stains the endothelial component of PMH [13]. PMH can also stain variably positive for CD31, CAM5.2, smooth muscle actin, and epithelial membrane antigen [7]. INI-1 positivity is the main differentiating factor between PMH and conventional epithelioid sarcoma. INI-1 expression is lost in 90% of epithelioid sarcomas, but retained in PMH [9, 14]. Beyond the INI-1 comparison, epithelioid sarcoma is positive for EMA and CD34, while PMH has variable positivity for EMA and is negative for CD34. CD34 can also be used to help differentiate PMH from EH and EA, since EH and EA will stain positive for CD34 [10] In addition, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma uniquely stains positive for calmodulin-binding transcription activator 1 (CAMTA1) due to the WWTR1-CAMTA1 fusion gene found over 90% of the time [15]. When comparing scSCC to PMH, both stain positive for keratin markers, however the endothelial markers CD31 and ERG help exclude this diagnosis. Exclusion of carcinoma is critical, given that SCC is much more frequently encountered in this anatomic location. PMH is distinctly negative for desmin, which can be used to distinguish it from tumors of myogenic origin [16, 17]. Molecular studies can also be used to demonstrate a characteristic translocation between chromosomes 7 and 19 that results in a SERPINE1-FOSB fusion gene [3, 4, 18]. This translocation is thought to be the driver mutation of this neoplasm, and is diagnostic for this entity [3, 4].

To the best of our knowledge, the current case represents only the second documented case of oral PMH. The previous case was reported by Rawal and involved the anterior maxillary gingiva in a 21-year-old female [7]. This patient was similarly treated with a wide local excision and remained disease free for two-years after definitive surgery. Although it is difficult to ascertain demographic information based on such a limited sample, it is interesting to note that both oral cases opposed the strong male predominance of PMH reported in other locations.

Conclusion

PMH is a vascular neoplasm of intermediate biologic potential which may rarely involve the oral cavity. Due to its behavior profile, it may mimic more commonly encountered, reactive oral lesions, leading to a delay in diagnosis and management. The current case represents only the second documented report of oral PMH and highlights the salient features of this entity.

Funding

The study received no commercial funding.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest declared by any other author.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: a distinctive, often multicentric tumor with indolent behavior. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:190–201. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ff0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirra JM, Kessler S, Bhuta S, et al. The fibroma-like variant of epithelioid sarcoma. A fibrohistiocytic/myoid cell lesion often confused with benign and malignant spindle cell tumors. Cancer. 1992;69:1382–1395. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920315)69:6<1382::AID-CNCR2820690614>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trombetta D, Magnusson L, von Steyern FV, et al. Translocation t(7;19)(q22;q13)—a recurrent chromosome aberration in pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma? Cancer Genet. 2011;204:211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walther C, Tayebwa J, Lilljebjorn H, et al. A novel SERPINE1-FOSB fusion gene results in transcriptional up-regulation of FOSB in pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma. J Pathol. 2014;232:534–540. doi: 10.1002/path.4322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ge Y, Lin X, Zhang F, Xu F, Luo L, Huang W, et al. A rare case of pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (PHE)/epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma (ES-H) of the breast first misdiagnosed as metaplastic carcinoma by FNAB and review of the literature. Diagn Pathol. 2019;14(1):79. doi: 10.1186/s13000-019-0857-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Pseudomyogenic (“fibroma-like”) variant of epithelioid sarcoma: a distinctive tumor type with a propensity for multifocality in a single limb but surprisingly indolent behavior. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(Suppl 1):13. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rawal YB, Anderson KM, Dodson TB. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: a vascular tumor previously undescribed in the oral cavity. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11:525–530. doi: 10.1007/s12105-016-0770-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:48–57. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amary MF, O’Donnell P, Berisha F, et al. Pseudomyogenic (epithelioid sarcoma-like) hemangioendothelioma: characterization of five cases. Skelet Radiol. 2013;42(7):947–957. doi: 10.1007/s00256-013-1577-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hornick JL. Practical soft tissue pathology: a diagnostic approach E-Book: a volume in the pattern recognition series. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017.

- 11.Takata T, Ito H, Ogawa I, Miyauchi M, Ijuhin N, Nikai H. Spindle cell squamous carcinoma of the oral region. Virchows Arch A. 1991;419(3):177–182. doi: 10.1007/BF01626345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doyle LA. Sarcoma classification: an update based on the 2013 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of Soft Tissue and Bone. Cancer. 2014;120(12):1763–1774. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pusztaszeri MP, Seelentag W, Bosman FT. Immunohistochemical expression of endothelial markers CD31, CD34, von Willebrand factor, and Fli-1 in normal human tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54(4):385–395. doi: 10.1369/jhc.4A6514.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hornick JL, Dal Cin P, Fletcher CD. Loss of INI1 expression is characteristic of both conventional and proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:542–550. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181882c54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shibuya R, Matsuyama A, Shiba E, Harada H, Yabuki K, Hisaoka M. CAMTA1 is a useful immunohistochemical marker for diagnosing epithelioid haemangioendothelioma. Histopathology. 2015;67(6):827–835. doi: 10.1111/his.12713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zin A, Bertorelle R, Dall’Igna P, Manzitti C, Gambini C, Bisogno G, et al. Epithelioid rhabdomyosarcoma: a clinicopathologic and molecular study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38(2):273–278. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miettinen M, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Esophageal stromal tumors: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 17 cases and comparison with esophageal leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(2):211–222. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200002000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hung YP, Fletcher CD, Hornick JL. FOSB is a useful diagnostic marker for pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:596–606. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]