Abstract

Double-hit lymphoma (DHL) is a unique subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterized by atleast two rearrangements involving MYC, BLC2, and/or BCL6. These lymphomas are uncommon and aggressive, responding poorly to typical chemotherapy regimens. Lymphomas rarely arise from the oral cavity or tonsils, and those presenting as a neck mass are predominantly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. To date, primary DHL of the tonsils has yet to be described in the literature. Here, we report a case of a 44 year-old male patient with well-controlled human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) who presented with a sore throat. He subsequently developed acute respiratory compromise due to a rapidly enlarging tonsillar mass. Pathologic and genetic analysis confirmed the presence of BCL6 and MYC rearrangements suggestive of DHL of the tonsils. In a young patient with HIV and a neck mass, it is essential that lymphoma remains on the list of differential diagnoses as prompt diagnosis and treatment may prevent complications from its rapid expansion.

Keywords: Double hit, Lymphoma, Tonsil, DLBCL, Large B-cell lymphoma

Introduction

Neck masses are a common occurrence in children and adult populations and are caused by various etiologies. Masses may be cystic, such as a thyroglossal duct cyst or lymphangioma, or solid, such as a lymphoma, neuroblastoma, or neurofibroma. Rarely, masses arise in the tonsils with diagnoses ranging from unilateral enlarged lymph nodes to primary carcinomas. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common malignant neoplasm of the tonsils, with long-term tobacco and heavy alcohol use being major contributors, as well as human papillomavirus [1, 2]. Lymphomas occur less frequently than SCC and represent 5% of oral malignancies [3]. While the classification of lymphomas is complex, the typical nomenclature begins by identifying if the mass is a Hodgkin lymphoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), with the former characterized by the binucleated Reed–Sternberg cell [4]. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a type of NHL and the most common to arise in the oral cavity [3]. Another, more rare type is the high-grade B-cell lymphoma (HGBL) which encompasses all large B-cell lymphomas (LBCL) with rearrangements in MYC, BCL2, and/or BCL6. When HGBLs contain more than one of these rearrangements, they are called ‘double-hit lymphomas’ (DHL) and are associated with increased aggression and worse outcome [5–8].

Among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive individuals, DLBCL is the most common NHL variant. An increased rate of MYC and BCL6 rearrangements portends an aggressive phenotype compared to lymphomas affecting the general population [9]. Despite these genetic influences, the mechanisms between HIV infection and subsequent development of DHL remain largely unknown. To our knowledge, DHL of the tonsils has not yet been described in the literature. Awareness of DHL occurrence at this site is necessary due to the rapid growth of these tumors with potential to cause acute airway compromise. Herein, we describe the first case of primary tonsillar DHL in a patient with HIV, a rapidly enlarging neck mass, and acute respiratory compromise.

Case Description

A 44-year-old male with a medical history significant for active HIV, treated with ongoing antiretroviral therapy, and Helicobacter pylori peptic ulcer disease presented to our clinic with a chief complaint of a sore throat. A social history was negative for smoking, tobacco, and alcohol use, and a family history was significant for maternal throat cancer. The patient denied fever, symptoms of an upper respiratory infection, shortness of breath, or hemoptysis. A subsequent throat culture was positive for group B streptococcus for which he was given a course of antibiotics. Despite the medications, the patient experienced worsening odynophagia and developed a muffled voice. Over the course of a month, he changed to a soft food and liquid diet and reported a weight loss of 35 lbs. His HIV viral load remained undetectable through the entirety of his work-up with a CD4+ count of 491.

Prior to arriving at our clinic, the patient had visited the emergency department (ED) for his symptoms. A peritonsillar abscess drainage was attempted but did not yield significant fluid for culture. A computed tomography (CT) scan performed at that time revealed a 3.1 × 2.5 cm mass (Fig. 1). The patient was scheduled for an outpatient fine needle aspiration (FNA); however, due to increased breathing difficulties, he returned to the ED 10 days later. A CT neck with IV contrast showed a 4.6 × 4.3 cm right tonsillar mass (Fig. 2). Right levels 2A and 1B/submandibular lymph nodes were enlarged.

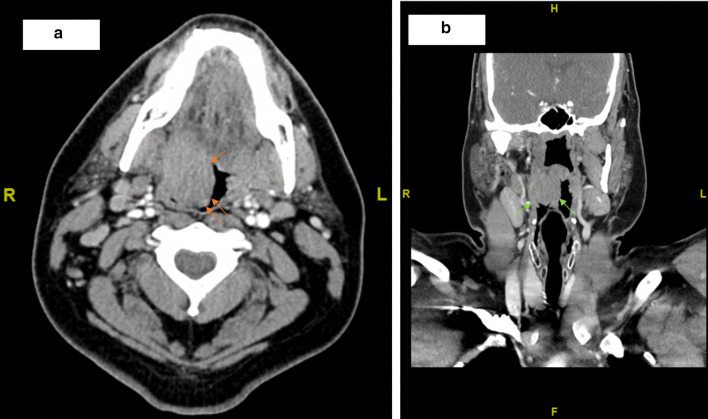

Fig. 1.

Initial computed tomography images revealed a 3.1 × 2.5 cm mass in the a axial (orange arrows) and b coronal (green arrows) planes

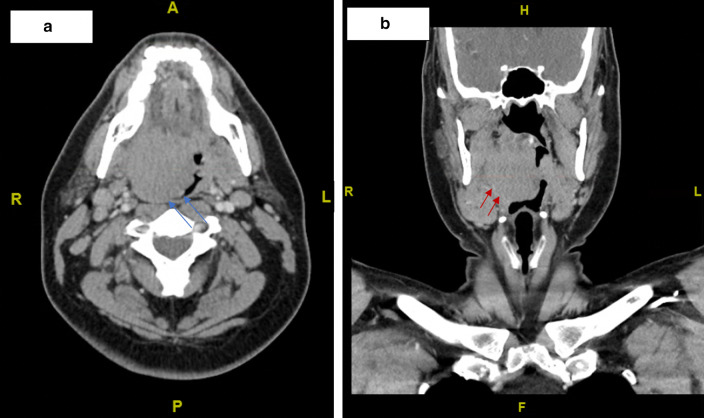

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography images revealed a 4.6 × 4.3 cm right tonsillar mass in the a axial (blue arrows) and b coronal (red arrows) planes. Increased airway impingement as compared to previous CT scan 10 days prior is noted

Examination of the oropharynx revealed a large exophytic tumor with a smooth capsule. The tumor was obstructing 80 to 90% of the oropharyngeal inlet. The patient underwent a right tonsillectomy with significant tumor debulking whereby the mass was grasped and excised down to the tonsillar fossa using Bovine electrocautery. The histopathologic findings were characteristic of an aggressive LBCL, non-germinal center derived (Fig. 3). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) showed BCL6 and MYC rearrangements, including a t(8;14) chromosomal translocation (Fig. 4). These results confirmed a double-hit HGBL. Additionally, the tumor was negative for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection by Epstein-Barr encoding region in situ hybridization (EBER-ISH). The patient underwent six cycles of R-EPOCH (Rituximab, Etoposide, Prednisone, Vincristine Sulfate, Cyclophosphamide, and Doxorubicin Hydrochloride) and responded well initially.

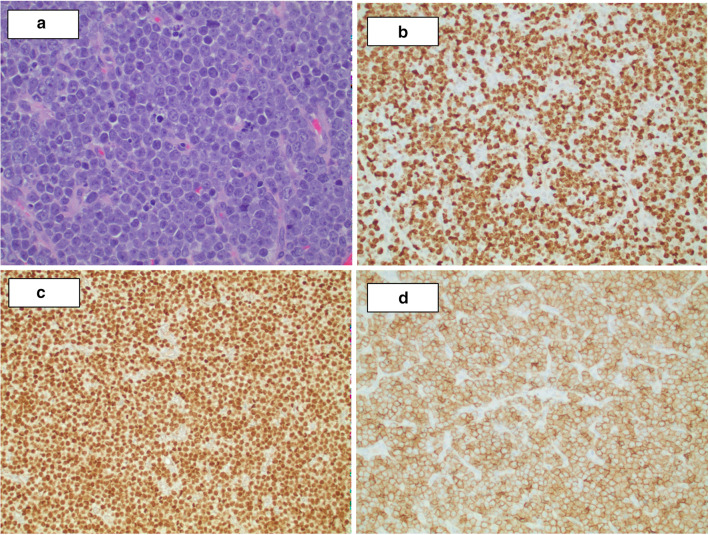

Fig. 3.

Histologic studies show solid sheets of atypical large lymphoid neoplastic cells with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli, brisk mitotic activity, and frequent apoptotic bodies. a H&E ×40, and immunohistochemical stains (×20), b Ki67, c PAX5 and d CD5 confirm overall findings consistent with an aggressive large B-cell lymphoma with non-germinal center derived phenotype (CD10−, BCL6−, MUM1+ , data not shown)

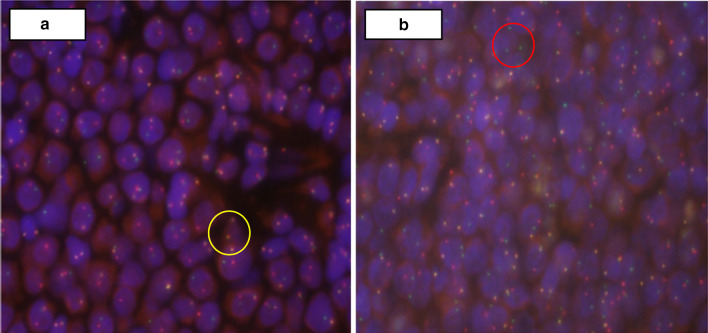

Fig. 4.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis was performed using split-signal probes to identify rearrangements in BCL2, BCL 6, MYC, t(8;14), and t(14;18). BCL6 rearrangements were detected (a) with 1 red, 1 green, and 1 yellow fusion (1R1G1F, yellow circle) probes, indicating splitting of one yellow probe. MYC rearrangements (b) were also detected with 1R1G1F probes, indicated by the red circle. t(8;14) (not shown) was also detected in the analysis. The BCL2 rearrangement and t(14;18) were not present

Five months later, the patient developed a right-sided facial swelling. CT showed an enlarging mass in the right parotid space with increased metabolic activity on positron emission tomography (PET) scan. FNA confirmed recurrence and EBER-ISH was again negative. He was started on DHAP (Dexamethasone, Cytarabine and Cisplatin) and tolerated it well with an impressive resolution of the facial swelling. The patient is undergoing continuous follow-up.

Discussion

Previously, LBCLs with MYC and BCL2 and/or, less commonly, BCL6 translocations were thought of as hybrid malignancies between Burkitt lymphoma (BL) and DLBCL. They were designated “B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable”. In the updated 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) classification system, this nomenclature was modified to the umbrella term HGBL which includes all LBCLs with MYC, BCL2, and/or BCL6 known as “double-/triple-hit” lymphomas [5–8]. The distinction becomes clinically significant as it is known that HGBLs tend to act aggressively and respond poorly to standard CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine, and prednisone) or rituximab-CHOP therapy [3, 6, 8, 10–13]. Rather, first-line treatment with R-EPOCH has been shown to reduce progression and disease burden [10, 13]. Like many other NHLs, HGBLs with MYC/BCL6 translocations, as seen in our patient, frequently present as extranodal masses with documented cases of involvement of the central nervous system, nasopharynx, palate, ribs, ovaries, liver, and, in one case, an effusion-based lymphoma [3, 7, 10–12, 14].

In general, lymphoma is the second most common primary malignancy to arise within the head and neck region after SCC. The rising rate of SCC in younger populations, due to an increase in high-risk HPV infections, contributes to the misdiagnosis of lymphoma-based tonsillar masses [15]. Both tonsillar lymphoma and SCC present with non-specific findings early in the disease course which pose diagnostic challenges for clinicians. Risk factors such as heavy alcohol and tobacco use are known to be associated with SCC but their absence does not necessarily suggest lymphoma due to the increased prevalence of HPV-mediated cancers in the region [1]. Not only should clinicians consider lymphoma in the evaluation of tonsillar masses, other possibilities include those of benign origin including lymphangiomas. These benign lesions may resemble their malignant tonsillar counterparts as they may be locally destructive. However, unlike the malignant tonsillar masses, lymphangiomas are usually congenital and present early in life with a smooth and pedunculated gross appearance [2]. The distinction in etiology and clinical presentation is crucial as it guides the treatment course and choice of chemotherapy.

Of the malignant tonsillar masses, most have a site predilection for Waldeyer’s ring (WR), a region comprising the lymphoid tissue of the pharynx including tonsillar tissues of the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and base of the tongue [16–18]. The palatine tonsils appear to be the highest occurring primary site within WR for NHL to manifest and DLBCL represents the most frequently encountered NHL subtype [17–20]. However, the authors are unaware of any reports of primary DHL of the tonsils to date. There is one published case report of tonsillar follicular lymphoma expressing BCL2 which subsequently underwent transformation into a triple-hit lymphoma of the frontal bone with a MYC/BCL2/BCL6 phenotype [10, 11]. Nonetheless, the involvement of the tonsils by HGBL with MYC/BCL6 translocations is a novel finding, especially in a patient with HIV.

Given the relatively new classification schema, there is scarce evidence describing the propensity of HIV-infected individuals to develop DHL. Previous evidence comparing DLBCL between HIV-infected patients and the general population demonstrates differing molecular characteristics between the two groups. HIV-infected patients with DLBCL tend to have a higher rate of MYC and BCL6 abnormalities and thus a worse prognosis compared to those without HIV [9]. Additionally, of the different translocations noted in HIV-infected patients, MYC appears to be the most common and confers a more aggressive clinical course [9, 21]. There is one case report of an HIV-related DHL that presented as peripheral blood involvement with both BCL2 and MYC translocations [22]. Further research is required to delineate the association between HIV-infection and subsequent development of DHL, with emphasis on the genetic phenotype as it pertains to treatment and prognosis. We describe a patient with HIV who developed primary DHL of the tonsils. While uncommon, this entity should be included on the differential diagnosis for neck and tonsillar masses due to its rapid growth and the potential for airway compromise.

Funding

There was no outside funding or grants received that assisted in this study.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chad Hinkle, Email: hinklec5@rowan.edu.

Gabriel S. Makar, Email: makarg3@rowan.edu

Joshua D. Brody, Email: brody-joshua@cooperhealth.edu

Nadir Ahmad, Email: ahmad-nadir@cooperhealth.edu.

Gord Guo Zhu, Email: zhu-gordguo@cooperhealth.edu.

References

- 1.Strome S, Savva A, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the tonsils: a molecular analysis of HPV associations. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1093–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mardekian S, Karp J. Lymphangioma of the palatine tonsil. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137(12):1837–1842. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0678-RS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frei M, Dubach P, Reichart PA, et al. Diffuse swelling of the buccal mucosa and palate as first and only manifestation of an extranodal non-Hodgkin ‘double-hit’ lymphoma: report of a case. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;16:69–74. doi: 10.1007/s10006-010-0254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas RK, Re D, et al. Epidemiology and etiology of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2002;13(4):147–152. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J. WHO Classification of tumour of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4. Lyon: IARC Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakr H, Cook JR. Identification of “double Hit” lymphomas using updated WHO criteria: insights from routine MYC immunohistochemistry in 272 consecutive cases of aggressive B-cell lymphomas. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2019;27(6):410–415. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliveira CC, Maciel-Guerra H, Kucko L, et al. Double-hit lymphomas: clinical, morphological, immunohistochemical and cytogenetic study in a series of Brazilian patients with high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Diagn Pathol. 2017;12(3):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13000-016-0593-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beham-Schmid C. Aggressive lymphoma 2016: revision of the WHO classification. Memo. 2017;10:248–254. doi: 10.1007/s12254-017-0367-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chao C, Silverberg MJ, Xu L, et al. A comparative study of molecular characteristics of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma from patients with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(6):1429–1437. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minhas H, Abdelmalek C, Khan M, et al. Double-hit lymphoma (MYC and BCL6) with involvement of skull and adnexal lesions: a case report and a review of the literature. Am J Case Rep. 2018;19:1035–1041. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.909400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu X, Zhang L, Wang Y, et al. Double-hit and triple-hit lymphomas arising from follicular lymphoma following acquisition of MYC: report of two cases and literature review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6(4):788–794. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pillai RK, Sathanoori M, Oss SB, et al. Double-hit B-cell lymphomas with BCL6 and MYC translocations are aggressive, frequently extranodal lymphomas distinct from BCL2 double-hit B-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37(3):323–332. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31826cebad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sesques P, Johnson NA. Approach to the diagnosis and treatment of high-grade B-cell lymphomas with MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements. Blood. 2017;129:280–288. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-02-636316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen BJ, Chen DYT, Kuo CC, et al. EBV-associated but HHV8-unrelated double-hit effusion-based lymphoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 2016;45(3):257–261. doi: 10.1002/dc.23638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quin Y, Lu L, et al. Hodgkin lymphoma involving the tonsil misdiagnosed as tonsillar carcinoma. Medicine. 2018;97(7):e9761. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohammadianpanah M, Omidvai S, Mosalei A, et al. Treatment results of tonsillar lymphoma: a 10-year experience. Ann Hematol. 2005;84(4):223–226. doi: 10.1007/s00277-004-0860-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee YH, Cho SG, Jung SE, et al. Analysis of treatment outcomes for primary tonsillar lymphoma. Radiat Oncol J. 2016;34(4):273–279. doi: 10.3857/roj.2016.01781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laskar S, Bahl G, Muckaden MA, et al. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the tonsils is a higher radiotherapy dose required? Cancer. 2007;110:816–823. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harabuchi Y, Tsubota H, Ohguro S, et al. Prognostic factors and treatment outcome in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of Waldeyer’s ring. Acta Oncol. 1997;36:413–420. doi: 10.3109/02841869709001289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamanaka N, Harabuchi Y, Sambe S, et al. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of Waldeyer’s ring and nasal cavity clinical and immunological aspects. Cancer. 1985;56:768–776. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850815)56:4<768::AID-CNCR2820560412>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morton LM, Kim CJ, Weiss LM, et al. Molecular characteristics of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in human immunodeficiency virus infected and -uninfected patients in the pre-highly active antiretroviral therapy and pre-rituximab era. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55(3):551–557. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.813499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathew T, Aqil B, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a deceptive leukemic presentation in the setting of HIV. Am J Clin Path. 2018;150(1):95. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqy097.230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]