Abstract

The aim of this study was to describe the clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features of four cases of anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) diagnosed through oral manifestations. Clinical data were collected from charts of a single oral pathology laboratory over a 5-year period (2014–2019) and all cases were evaluated by conventional hematoxylin and eosin staining and an extended immunohistochemical panel comprising CD45, CD20, CD3, CD4, CD7, CD30, CD99, CD138, cytokeratin AE1/AE3, EMA, ALK, MUM-1 and Ki-67. The study included 3 male (75%) and 1 female (25%) patients, with a median age of 44 years. The most common intraoral affected site was the alveolar ridge (50%). Clinically, all cases were characterized as an ulcerated bleeding mass. Microscopically, proliferation of anaplastic large lymphoid cells with medium to large-sized, abundant amphophilic to eosinophilic cytoplasm and eccentric nuclei were observed. All cases were positive for CD30, while two cases strongly express ALK. Two patients died of the disease. Careful correlation of clinical, morphological and immunohistochemical data are necessary to establish the diagnosis of oral manifestation of ALCL since its microscopical features may mimic other malignant tumors. Clinicians and pathologists should consider ALCL in the differential diagnosis when evaluating oral ulcerated swellings exhibiting large lymphoid cells in patients with lymphadenopathy.

Keywords: Anaplastic large cell lymphoma, Oral mucosa, Immunohistochemistry

Introduction

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a subgroup of T-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) that accounts for 1% to 8% of all NHLs and 12% of all T-cell lymphomas [1–6], being microscopically characterized by proliferation of anaplastic large lymphoid cells that strongly express CD30 antigen [7–9]. The ALCLs are further subdivided into three categories according to clinical and immunohistochemical criteria in primary systemic anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) positive ALCL, primary systemic ALK-negative ALCL, and primary cutaneous ALCL [10–12]. The ALK-positive ALCLs usually occur in males in their first decades of life showing good response to chemotherapy and favorable prognosis; whereas ALK-negative ALCLs occur in elderly individuals with comparably poor outcome [6–9].

The oral involvement of ALCL is rare, and to the best of our knowledge, only 30 cases of ALCL have been published in the English-language literature so far (Table 1) [3–19]. Herein, we report four additional cases of ALCL diagnosed through oral and maxillofacial manifestations.

Table 1.

Clinical features of anaplastic large cell lymphoma with oral involvement reported in the English-language literature and the present cases

| Author | Age/gender | Location | Clinical features | Radiographic findings | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Takahashi et al. [3] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Hicks et al. [4] | 36/M | Retromolar trigone | Mass with ulcerated surface | Diffuse radiolucency with poorly margins | DOD |

| 42/M | Retromolar trigone | Enlargement surrounding a crateriform ulcer | NR | DOD | |

| Willard et al. [5] | 12/F | Gingiva | Scaly, swollen, and bleeding gingival surface | Bone resorption causing teeth displacement | NED |

| Papadimitriou et al. [6] | 12/M | Hard palate | Mass involving palate, nasal cavity and orbit | NR | NR |

| Rosenberg et al. [7] | 75/F | Upper gingiva | Periodontitis and redness of the gingiva | Bone resorption adjacent to teeth 11, 12 and 13 | NR |

| 61/M | Lower gingiva | Well-delimited ulceration | NR | NR | |

| Chandu et al. [8] | 48/M | Upper lip | Firm swelling lesion | NR | NR |

| Chim et al. [9] | 76/F | Upper lip | Swelling with a well delimited ulceration | NR | NED |

| Born et al. [10] | 65/F | Hard palate, buccal mucosa, and floor of the mouth | Well-delimited ulceration | NR | DOD |

| Savarrio et al. [11] | 77/M | Soft palate | Mass with ulceration | NR | NED |

| Notani et al. [12] | 77/Ma | Tongue | Nodular lesion with ulceration | Low density mass | NED |

| Matsumoto et al. [13] | 76/F | Upper and lower gingiva | Gingival swelling | Bone resorption | NED |

| Grandhi et al. [14] | 34/F | Upper gingiva | Ulcerated mass with erythematous border | NR | NED |

| 53/M | Tongue | Mass with ulcerated area | NR | NR | |

| Rozza de Menezes et al. [15] | 57/M | Gingiva | Lobulated and pedunculated reddish nodule with bleeding | Bone resorption | DOD |

| Wang et al. [16] | 23/M | Upper lip | NR | NR | NED |

| 72/F | Lower left gingiva | NR | NR | NED | |

| 74/M | Lower left gingiva | NR | NR | NED | |

| 60/M | Soft palate | NR | NR | NED | |

| 57/M | Lower right gingiva | NR | NR | NED | |

| 56/M | Ventral tongue | NR | NR | NED | |

| 45/M | Frenulum linguae | NR | NR | NED | |

| 47/M | Ventral tongue | NR | NR | NED | |

| 52/F | Upper right gingiva | NR | NR | NED | |

| 43/F | Lower right gingiva | NR | NR | NED | |

| 67/M | Lower lip | NR | NR | NED | |

| Narwal et al. [17] | 48/M | Hard palate | Rapidly enlarging swelling | Bone resorption | NED |

| Lapthanasupkul et al. [18] | 55/F | Hard palate | Lobulated mass | Osteolytic lesion | AWD |

| Meconi et al. [19] | 40/M | Hard palate | Erythematous nodule | NR | NED |

| Present cases | 88/M | Alveolar ridge | Multilobular ulcerated swelling showing reddish a | Discrete well-defined superficial bone resorption | DOD |

| 18 Ma | Submandibular region and floor of the mouth | Painful ulcerated swelling | Hyperdense area | NED | |

| 51/M | Alveolar ridge | Ulcerated bleeding mass | Well-defined osteolytic lesion | AWD | |

| 22/Fa | Hard palate | Ulcerated reddish mass | Hyperdense image | DOD |

M male, F female, NR not reported, DOD dead of disease, NED no evidence of disease, AWD alive with disease

aALK positive

Materials and Methods

Four cases of oral involvement of ALCL were retrieved from the files of the Oral Pathology Laboratory of Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) Brazil for this retrospective cross-sectional study from 2014 to 2019. Demographic, clinical, and radiological data of the patients were obtained from the laboratory records. All cases were analysed under light microscopy using 3 μm sections on histologic slides stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). This study was carried out following the Helsinki Declaration for study involving human subjects.

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed in paraffin sections (3 μm thick, on silane-coated histologic slides) from formalin-fixed material that were dehydrated and deparaffinized according to standard procedures. Heat-induced antigen retrieval was then performed. The slides were incubated overnight with primary antibodies (Table 2) and secondary antibody used was EnVision® + Dual Link/Peroxidase (Dakocytomation®). Positive and negative controls were included in all reactions. A descriptive analysis of the clinical and microscopic findings is provided in the present study. The labeling index for Ki-67 was defined taking into consideration the percentage of cells expressing nuclear positivity out of the total number of cells, counting 1000 cells per slide in 10 high-power fields (× 400).

Table 2.

Antibodies used for immunohistochemical evaluation of anaplastic large cell lymphoma with oral involvement

| Antibody | Clone/source | Dilution | Results Case 1 | Results Case 2 | Results Case 3 | Results Case 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD45 | 2B11 + PD7/26, Dako®a | 1:200 | + | + | + | + |

| CD20 | L26, Dako®a | 1:400 | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| CD3 | Polyclonal, Dako®a | 1:200 | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| CD4 | SP35, SpringBioscienceb | 1:300 | ± | Neg | Neg | + |

| CD7 | MRQ-12, Cell Marquec | 1:300 | ± | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| CD30 | BerH2, Dako®a | 1:300 | + | + | + | + |

| CD99 | EPR3097Y, Cell Marquec | 1:300 | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| CD138 | Mi15, Dako®a | 1:100 | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| CK AE1/AE3 | AE1/AE3, Dako®a | 1:400 | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| EMA | E29, Dako®a | 1:2000 | Neg | + | + | + |

| ALK | Polyclonal, Dako®a | 1:200 | Neg | + | Neg | + |

| MUM-1 | MUM-1p, Dako®a | 1:300 | Neg | Neg | Neg | + |

| Ki-67 | MIB-1, Dako®a | 1:200 | 90% | 90% | 95% | 90% |

CK Cytokeratin, EMA Epithelial membrane antigen, ALK Anaplastic lymphoma kinase

+ Positive, ± focally positive, Neg negative

aDako, Dako Corporation, California, USA

bSpringBioscience, USA

cCell Marque, USA

Results

Four ALCL cases with oral involvement were found in 5 years, representing 0.06% from a total of 6214 oral biopsies cases evaluated in this period. The clinical and immunohistochemical findings are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 respectively. The study included 3 male (75%) and 1 female (25%) patients, with a mean age of 44 years (range 18–88 years), who were affected mainly by ulcerated bleeding masses, which were located in the alveolar ridge in half of the cases.

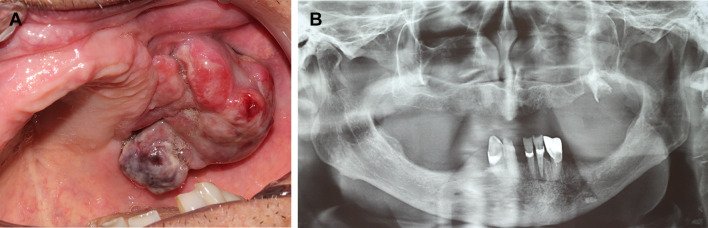

The first patient was an 88-years-old male referred for evaluation of a swelling in the posterior upper alveolar ridge lasting 20 days, which caused bleeding and interfering in the use of the total denture. The past medical history was unremarkable. Intraoral examination revealed a pedunculated multilobular swelling measuring 5 × 4 cm, showing reddish to purplish coloration, covered by ulcerated mucosa and located at the posterior alveolar ridge of the left maxilla (Fig. 1a). The lesion was fibroelastic in consistency and asymptomatic. Panoramic radiography revealed a discrete well-defined superficial bone resorption of the upper posterior alveolar ridge, indicating the extra-osseous location of the lesion, which was associated with an upper molar with crown destruction (Fig. 1b). Routine laboratory studies showed normal values. Under the main clinical hypotheses of reactive lesion, and malignant primary or metastatic tumors, an incisional biopsy was performed.

Fig. 1.

Clinical and radiographical features of ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma with oral manifestation (case 1). a Intraoral examination showing a pedunculated multilobular swelling with reddish and purplish areas, covered by ulcerated mucosa located at the posterior alveolar ridge of the left maxilla. b Panoramic radiography exhibiting a discrete well-defined superficial bone resorption of the alveolar ridge

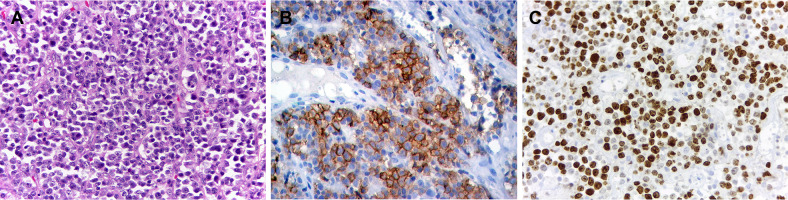

Microscopically, it was identified a uniform proliferation of medium to large-sized atypical cells with abundant amphophilic to eosinophilic cytoplasm, with nuclear chromatin finely dispersed and small basophilic nucleoli. Cells with eccentric, horse-shoe, or kidney-shaped nuclei and mitotic figures were also observed (Fig. 2a). The microscopic differential diagnoses were lymphoma, poorly differentiated carcinoma, amelanotic melanoma and rhabdomyosarcoma. By immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells showed strong CD30 expression in more than 75% of neoplastic cells in a membrane and cytoplasmic pattern. Ki-67 positive staining was observed in 90% of tumor cells. Positive staining was also identified with CD45, while CD4 and CD7 were focally positive (Fig. 2b, c). Based on clinical, histopathological, and immunohistochemical findings, the final diagnosis was of a primary ALK-negative ALCL of the oral cavity. The patient was then referred to a hematology-oncology service, and a hyperdense mass was observed in his right lung. Patient was then submitted to chemotherapy, but unfortunately, he died 6 months after the diagnosis.

Fig. 2.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical features of ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma with oral manifestation (case 1). a Uniform proliferation of medium to large-sized atypical cells with abundant amphophilic to eosinophilic cytoplasm, with nuclear chromatin finely dispersed and small basophilic nucleoli (HE, ×400). Tumor cells were positivity for b CD30 and c Ki-67 (Immunoperoxidase, ×400)

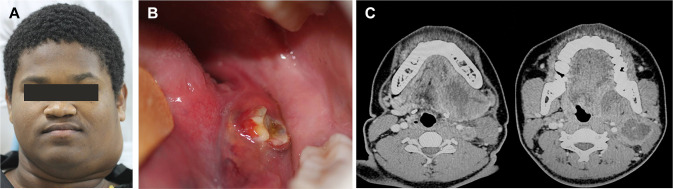

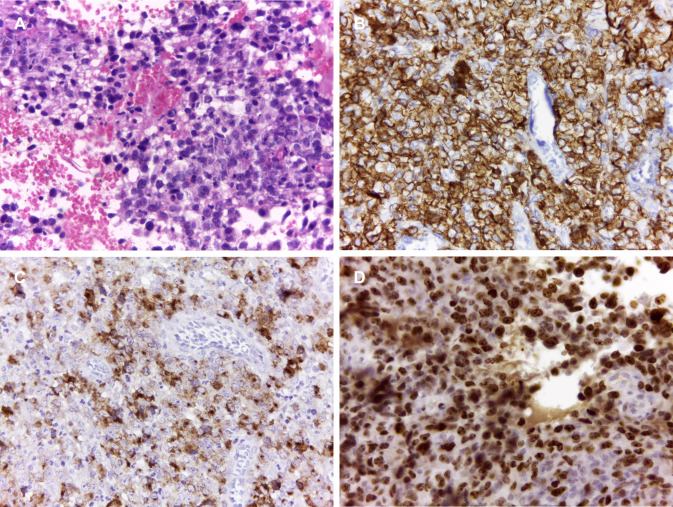

The second patient was an otherwise healthy 18-year-old male referred for evaluation of a painful swelling in the neck and ulcer in the oral cavity lasting 30 days, which was interfering in the mastication. The patient was a nonsmoker and his medical history did not reveal other relevant information. The extraoral examination showed a tender swelling in the left submandibular region measuring 3 × 4 cm (Fig. 3a). Intraoral examination revealed a swelling on the left side of the posterior floor of the mouth, showing a small superficial ulceration of reddish to yellowish coloration (Fig. 3b). Image exams revealed a hyperdense round tumor of 4 × 5 cm affecting the submandibular lymph nodes, showing a central hypodense area compatible with necrosis (Fig. 3c). With the main clinical hypotheses of a malignant mesenchymal tumor and lymphoma, an incisional biopsy was performed. Microscopically, proliferation of medium to large-sized atypical cells with abundant amphophilic to eosinophilic cytoplasm and eccentric nuclei, with mitotic figures and reactive macrophages were observed (Fig. 4a, b). By immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells were positive for CD45, EMA, and CD30. ALK was positive in a nuclear and cytoplasmic pattern. Ki-67 index was 90% (Fig. 4c–f). The final diagnosis was of a primary ALK-positive ALCL. The patient was then referred to a hematology-oncology service and submitted to chemotherapy. The patient is under 2 years of follow-up with no signs of recurrence.

Fig. 3.

Clinical and radiographical features of ALK-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma with oral manifestation (case 2). a The extraoral examination showed a swelling in the left submandibular region and b intraoral examination revealed an ulcerated mass showing reddish and yellowish areas, located at the floor of the mouth. c Image exams revealed a central hyperdense area compatible with necrosis in the submandibular lymph node region

Fig. 4.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical features of ALK-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma with oral manifestation (case 2). a Proliferation of atypical cells with abundant amphophilic to eosinophilic cytoplasm and eccentric nuclei. b Reactive macrophages were also observed (HE, 400X). Tumor cells showed a strong positivity for c CD45, d EMA, e CD30 and f ALK (Immunoperoxidase, ×400)

The third patient was a 51-year-old male referred for evaluation of a painless soft tissue mass on right alveolar ridge of the mandible lasting three months. Extraoral examination revealed a facial asymmetry involving the right body of the mandible (Fig. 5a). Intraoral examination revealed a mass with irregular surface on the posterior lower alveolar ridge of the right side, measuring 3 cm (Fig. 5b). The mass was ulcerated and soft in consistency, easily bleeding and covered by yellow and red mucosa. Panoramic radiograph showed a well-defined osteolytic lesion causing irregular destruction of the right mandible (Fig. 5c). Microscopically, a dense infiltration of round tumour cells was recognized. These atypical cells were highly pleomorphic with medium to large-sized and contained abundant basophilic cytoplasm and pleomorphic nuclei (Fig. 6a). On immunohistochemical examination, tumor cells showed a strong reactivity to CD45, CD30, and EMA. Ki-67 index was 95% (Fig. 6b–d). The diagnosis of primary ALK-negative ALCL was established. The patient was referred to a heamato-oncologist for treatment and is currently undergoing chemotherapy with initial remission after 4 months of treatment.

Fig. 5.

Clinical and radiographical features of ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma with oral manifestation (case 3). a The extraoral examination showed a swelling in the right mandible and b intraoral examination revealed a mass with irregular surface on the posterior alveolar ridge of the right mandible. c Panoramic radiograph showed a well-defined osteolytic lesion causing destruction of the right mandible

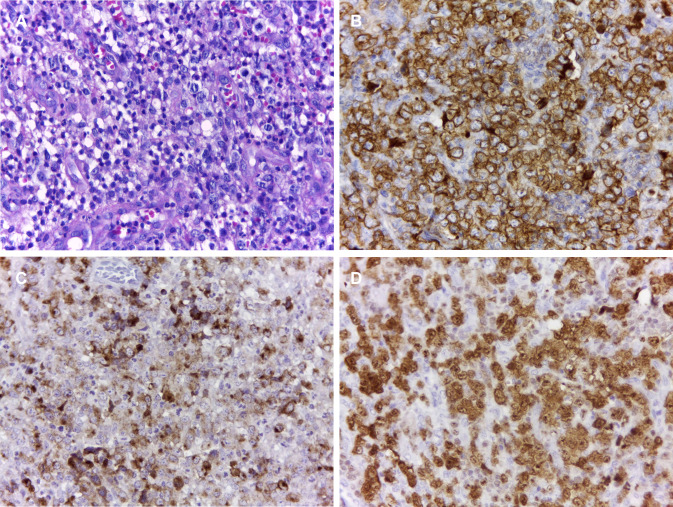

Fig. 6.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical features of ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma with oral manifestation (case 3). a Infiltration of atypical cells with medium to large-sized and contained abundant basophilic cytoplasm and pleomorphic nuclei (HE, ×400). Tumor cells showed a strong positivity for b CD30, c EMA, and d Ki-67 (Immunoperoxidase, ×400)

The fourth patient was a 22-year-old female referred for evaluation of a painless exophytic mass on the hard palate of three months evolution. Intraoral examination revealed an ulcerated reddish mass of irregular surface on the hard palate, showing a central depression and measuring 4 cm (Fig. 7a). A computed tomography showed a hyperdense image involving the nasal cavity, the left ethmoidal sinus, and the right and left maxillary sinus, confirming the hard palate destruction and the tumor epicentre in the sinonasal region (Fig. 7b). Microscopically, there was a dense infiltration of pleomorphic round tumour cells of medium to large size (Fig. 8a), which were positive for CD45, CD30, MUM-1, CD4, and EMA. ALK was positive in a nuclear and cytoplasmic pattern. Ki-67 index was 90% (Fig. 8b–d). Based on the histopathological and immunohistochemical findings, the diagnosis was of primary ALK-positive ALCL. The patient was transferred to a heamato-oncologist but died before undergoing chemotherapy.

Fig. 7.

Clinical and radiographical features of ALK-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma with oral manifestation (case 4). a Intraoral examination revealed an ulcerated red mass with irregular surface on the hard palate. b Computed tomography showed a hyperdense image involving the nasal cavity, the left ethmoidal sinus, and the right and left maxillary sinus.

Fig. 8.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical features of ALK-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma with oral manifestation (case 4). a Proliferation of atypical lymphoid cells (HE, ×400). Tumor cells showed a strong positivity for b CD30, c EMA, and d ALK (Immunoperoxidase, ×400)

Discussion

ALCL is currently subcategorized into three groups, the first being part of the spectrum of CD30 + T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders (primary cutaneous ALCL and lymphomatoid papulosis), and the other two groups are composed of primary systemic ALCL (ALK-positive and ALK-negative) [1, 2, 20]. CD30 + lymphoproliferative diseases are the second most common primary cutaneous T-cell disorders, the most common being mycosis fungoides [8]. The classification of CD30 + lymphoproliferative disorders remains controversial since lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) and ALCL might share similar histopathological and immunophenotypic features [12]. Lymphomatoid papulosis is characterized by recurrent papules, nodules, and plaques that follow a benign clinical course [14]. In contrast, although primary cutaneous ALCLs appear histopathologically similar, they follow a malignant course and may occur de novo or as a malignant transformation from lymphomatoid papulosis. Primary cutaneous ALCLs are identified as single or multiple skin lesions affecting older patients, being usually negative for ALK negative [13].

Primary systemic ALK-positive and ALK-negative ALCLs commonly affect lymph nodes, especially in the cervical and inguinal regions [16]. ALK-positive ALCL may also involve extranodal sites such as skin, bone, soft tissues, lung, and liver in 60% of cases, while ALK-negative ALCL tends to involve skin, liver, bone, bone marrow, subcutaneous tissue, the gastrointestinal tract and the oral cavity [13–15]. Only 30 cases of primary ALCL with oral manifestation have been published in the English-language literature [3–19] (Table 1). The average age of the patients is 53.7 years (ranging from 12 to 77 years), with predilection for females (1.8:1). The gingiva/alveolar ridge is the most common affected site (12 cases), followed by palate (8 cases), tongue (6 cases), lip (4 cases), and retromolar trigone (2 cases). The most common clinical feature of oral ALCL is a nodule or mass with ulcerated surface, and the main radiographic finding was bone resorption, as also observed in our series [3–19].

Microscopically, ALCL is characterized by proliferation of large, anaplastic lymphoid cells with eccentric horse-shoe or kidney-shaped nuclei and one or more prominent nucleoli [9–11]. The cells are pleomorphic with abundant cytoplasm and show cohesive growth, and numerous mitotic figures may be present [15]. The phenotypic profile of neoplastic cells in ALCL includes CD30-positivity that demonstrates membrane and sometimes dot-like Golgi staining. The immunomarkers may also include epithelial membrane antigen, positive in 60%-70% of ALK-positive ALCL cases; and CD3, positive in 45% ALK-negative cases and 12% in ALK positive cases [11–15]. A minority of cases also expresses CD4 or CD8 with a predominance of CD4 [13]. Approximately 80% of ALK-positive cases are positive for TIA1, granzyme B, and perforin, in contrast to only 50% of ALK-negative cases [13]. About 20% of cases, there is lack of CD45 expression with the presence of CD15 positivity. Epstein-Barr virus and PAX5 are usually negative and thus help to differentiate from Hodgkin lymphoma [10–12].

The histopathological differential diagnosis typically includes poorly differentiated carcinoma, amelanotic melanoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and anaplastic variant of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL); therefore, an immunohistochemistry examination is helpful to distinguish it from those other disease entities [15]. Most carcinoma cells are positive for epithelial markers, unlike an ALCL. However, an ALCL is sometimes positive for EMA; therefore, careful examination is required to distinguish them [13]. ALCL must be distinguished from other lesions that may contain CD30-positive cells, i.e., a malignant melanoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, anaplastic variant of DLBCL, and adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma [14]. Tumor cells in malignant melanomas often react with melanocyte associated antigen like HMB-45, Melan-A and S-100 protein, whereas ALCL tumor cells do not have such reactivity. Furthermore, Hodgkin cells and Reed-Sternberg cells from Hodgkin disease are usually positive for CD15 and have Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) protein or RNA, whereas ALCL cells do not have those features.

It is well known that ALK-positive ALCL is a distinctive entity clinically and pathogenetically and should be differentiated from ALK-negative ALCL cases [12]. The tumors that show a positive reaction for ALK usually have less cell proliferation and can show a relatively better prognosis [12–15]. Recently, studies have proposed that proteins such as aberrant fusion protein (NPM-ALK), JAK-STAT, and PI3K/STAT may be a potential target in ALK-positive lymphomas [12, 20]. The findings about specific antigens also suggest that ALK represents an ideal tumor antigen for vaccination-based therapies of ALCL and other ALK-positive tumors. On the other hand, the cases of ALK-negative ALCL show an inaccurate behavior with a relatively unfavorable prognosis [12–14]. To make the diagnosis of ALK-negative ALCL, there must be a large cell predominant population with abundant cytoplasm and pleomorphic, embryo or hallmark nuclei or wreath-like giant cells, and strong CD30 expression with a membrane and Golgi distribution in virtually every cell with a highly anaplastic T-cell phenotype [13]. Considering the oral ALCL cases published in the literature, only 1 case was ALK-positive [12], while 18 cases were ALK-negative and in 11 cases this information was not available [3–19].

Primary systemic ALK-positive cases usually respond well to chemotherapy, mainly with brentuximab vedotin, an anti-CD30 antibody conjugated to monomethyl auristatin E, and have good prognosis in comparison with primary systemic ALK-negative cases, which have a poorer prognosis with unpredictable clinical behavior [12–14, 19]. Only 30% to 50% of cases achieve stable complete remission with use of standard regimens in comparison with 90% complete remission in ALK-positive cases. A 30% to 40% 5-year survival rate is noted in systemic ALK-negative cases as opposed to 80% to 93% survival in ALK-positive cases [12]. From all ALCL cases with oral manifestation reported in the literature, 19 patients had no evidence of disease, and 4 died of disease [3–19].

In summary, ALCL with oral manifestation is a rare entity, with microscopical features that may mimic other malignant tumors. Careful morphological and immunohistochemical analyses, correlating with clinical local and systemic data are necessary to establish the diagnosis of ALCL from an oral biopsy. Clinicians and oral pathologists should consider ALCL in the differential diagnosis when evaluating oral ulcerated swellings with large lymphoid cells.

Funding

No funding was received.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All of authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest and no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This study was carried out following the Helsinki Declaration for study involving human subjects.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Falini B, Lamant-Rochaix L, Campo E, et al. Anaplastic T cell lymphoma, ALK-positive. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, et al., editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARC; 2017. pp. 413–418. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldman AL, Harris NL, Stein H, et al. Anaplastic T cell lymphoma, ALK-negative. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, et al., editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. IARC: Lyon; 2017. pp. 418–421. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi H, Fujita S, Okabe H, Tsuda N, Tezuka F. Immunophenotypic analysis of extranodal non-Hodgkin's lymphomas in the oral cavity. Pathol Res Pract. 1993;189:300–311. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(11)80514-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hicks MJ, Flaitz CM, Nichols CM, Luna MA, Gresik MV. Intraoral presentation of anaplastic large-cell Ki-1 lymphoma in association with HIV infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;76:73–81. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90298-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willard CC, Foss RD, Hobbs TJ, Auclair PL. Primary anaplastic large cell (KI-1 positive) lymphoma of the mandible as the initial manifestation of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in a pediatric patient. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;80:67–70. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(95)80018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papadimitriou JC, Abruzzo LV, Bourquin PM, Drachenberg CB. Correlation of light microscopic, immunocytochemical and ultrastructural cytomorphology of anaplastic large cell Ki-1 lymphoma, an activated lymphocyte phenotype. A case report. Acta Cytol. 1996;40:1283–1288. doi: 10.1159/000334022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg A, Biesma DH, Sie-Go DM, Slootweg PJ. Primary extranodal CD3O-positive T-cell non-Hodgkins lymphoma of the oral mucosa. Report of two cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;25:57–59. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(96)80013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandu A, Mitchell DA, Corrigan AM. Cutaneous CD30 positive large T cell lymphoma of the upper lip: a rare presentation. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;35:193–195. doi: 10.1016/S0266-4356(97)90563-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chim CS, Chan AC, Raymond L. Primary CD30-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the lip. Oral Oncol. 1998;34:313–315. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(98)80014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Born S, Gaber G, Willgeroth K, Wagner U, Haneke E, Marsch WC. Metastasising malignant lymphoma mimicking necrotising and hyperplastic gingivostomatitis. Eur J Dermatol. 1999;9:569–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savarrio L, Gibson J, Dunlop DJ, O'Rourke N, Fitzsimons EJ. Spontaneous regression of an anaplastic large cell lymphoma in the oral cavity: first reported case and review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 1999;35:609–613. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(99)00034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Notani K, Shindoh M, Takami T, Yamazaki Y, Kohgo T, Fukuda H. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) in the oral mucosa with repeating recurrence and spontaneous regression of ulceration: report of a case. Oral Med Pathol. 2002;7:79–82. doi: 10.3353/omp.7.79. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsumoto N, Ohki H, Mukae S, Amano Y, Harada D, Nishimura S, Komiyama K. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma in gingiva: case report and literature review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:e29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grandhi A, Boros AL, Berardo N, Reich RF, Freedman PD. Two cases of CD30+, anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma with oral manifestations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;115:e41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rozza-de-Menezes RE, Jeronimo Ferreira S, Lenzi Capella D, Schwartz S, Willrich AH, de Noronha L, Batista Rodrigues Johann AC, Couto Souza PH. Gingival anaplastic large-cell lymphoma mimicking hyperplastic benignancy as the first clinical manifestation of AIDS: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dent. 2013;2013:852932. doi: 10.1155/2013/852932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang W, Cai Y, Sheng W, Lu H, Li X. The spectrum of primary mucosal CD30-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders of the head and neck. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;117:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Narwal A, Yadav AB, Prakash S, Gupta S. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma of hard palate as first clinical manifestation of acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Contemp Clin Dent. 2016;7:114–117. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.177115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lapthanasupkul P, Songkampol K, Boonsiriseth K, Kitkumthorn N. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the palate: a case report. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;120:172–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2018.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meconi F, Secchi R, Palmieri R, Vaccarini S, Rapisarda VM, Giannì L, Esposito F, Provenzano I, Nasso D, Pupo L, Cantonetti M. Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the oral cavity successfully treated with brentuximab vedotin. Case Rep Hematol. 2019;17(2019):9651207. doi: 10.1155/2019/9651207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leventaki V, Bhattacharyya S, Lim MS. Pathology and genetics of anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2020;37:57–71. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2019.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]