Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is the main cause of infectious mononucleosis (IM), a self-limiting infection among immunocompetent patients. EBV is also implicated in the development of several malignancies. We describe a case of a previously healthy 34-year-old man who presented with non-tender, enlarging, right cervical lymphadenopathy for over a year that was associated with significant weight loss, fevers, and night sweats. Two fine needle core biopsies showed inconclusive then reactive tissue, respectively. A third excisional biopsy demonstrated a reactive lymph node with EBV-positive IM. There was no evidence of lymphoma by histologic examination or flow cytometry. A diagnosis of chronic active EBV (CAEBV) was rendered. Subsequent lymph node debulking six months later showed classic Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL) positive for EBV. The patient underwent chemotherapy with full treatment response. This is an unusual presentation of EBV infection that led to either a delayed onset or delayed diagnosis of CHL.

Introduction

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is regarded as the primary cause of infectious mononucleosis (IM) and is typically self-limiting among immunocompetent patients. Symptoms of IM include fever, fatigue, and lymphadenopathy/glandular adenopathy, with lymph node swelling most commonly seen in the cervical region [12]. EBV can also cause chronic active Epstein-Barr virus (CAEBV) infection [10]. CAEBV is an uncommon disease that primarily affects children and is characterized by symptoms of fever, lymph node swelling, and hepatosplenomegaly with elevated liver serum transaminase levels [15]. Adult-onset cases may be more progressive and have a less favorable prognosis as compared to pediatric patients [1]. Currently, there is no established treatment regimen for this disease. Hematopoietic stem cell therapy (HSCT) has been a pivotal treatment and is the only known curative therapy, with varying degrees of success [5, 6, 15]. Acyclovir can theoretically be used for treatment of primary EBV infection but has no proven effect on CAEBV infection[3].

EBV is also implicated in the development of several lymphoproliferative disorders and lymphomas including Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s types [4]. More rarely, EBV infection can present with features of lymphoma without underlying malignancy [7]. Non-malignant EBV infection may have a different immunophenotypic profile than typical classic Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL). On biopsy, it may mimic other types of lymphoma such as non-germinal center type diffuse large B-cell lymphoma as the atypical lymphoid infiltrates are MUM1/IRF4+, CD10-, and BCL-6-[7]. While the presentation of an enlarging neck mass accompanied by B symptoms of night sweats, fatigue, and weight loss is concerning for lymphoma, non-malignant EBV infection is a common imitator. We present an unusual case of the opposite scenario, where lymphoma mimicked EBV infection resulting in a delayed diagnosis of CHL.

Case Presentation

A previously healthy 34-year-old man presented with nontender, enlarging right cervical lymphadenopathy for over a year (Fig. 1). At presentation, the patient reported significant weight loss of 78 pounds, decreased appetite, weakness, joint pain, and night sweats. On computed tomography (CT) scan, a prominent right level IIb lymph node was identified, measuring 5.0 cm in greatest diameter, as well as multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the right neck (Fig. 2). The lymphadenopathy was limited to the neck as CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis were unremarkable. An initial needle biopsy was inconclusive and a second needle biopsy showed reactive tissue. Excisional biopsy of a lymph node demonstrated EBV by in-situ hybridization (ISH) consistent with infectious mononucleosis. Concurrent flow cytometry and histopathology showed no evidence of B-cell lymphoma or T-cell surface antigen deletion or expansion, and the patient was diagnosed with chronic active Epstein-Barr virus (CAEBV).

Fig. 1.

Photograph of the right neck mass

Fig. 2.

CT of neck mass, lymph node indicated by the arrow

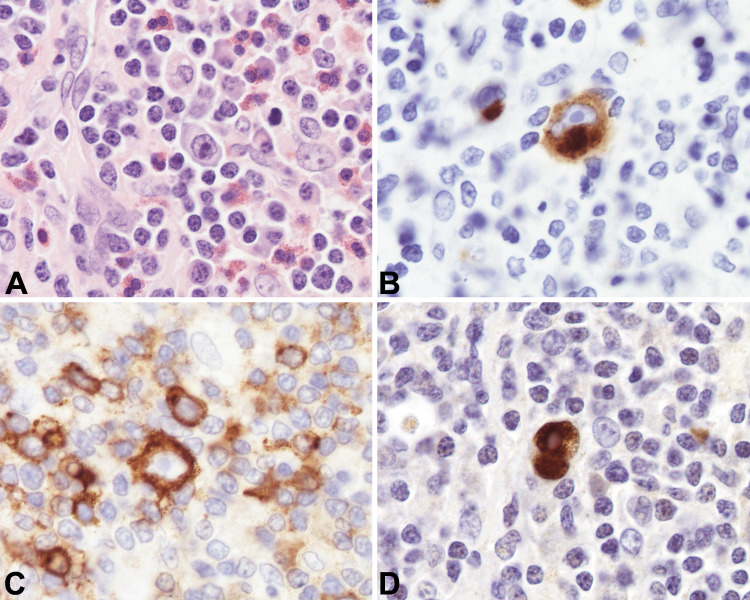

Six months later, the patient underwent elective removal of the neck mass. Tissue section evaluation by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain revealed a partly effaced and distorted lymph node involved by a mixed population of inflammatory cells including histiocytes, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and eosinophils. Scattered residual intact follicles with germinal centers were identified with the following immuno profile: CD10+, BCL6+, BCL2-, and CD23 highlighting follicular dendritic meshwork. The interfollicular areas showed scattered Reed-Sternberg cells that had enlarged nuclei with irregular nuclear contours, prominent nucleoli, and abundant pale-staining cytoplasm. Binucleated and multinucleated forms were noted amongst a background of small lymphocytes and scattered eosinophils. The large atypical cells were positive for CD30, CD15, PAX5 (weak), OCT-2, and BOB1, and negative for CD20 and CD45. In situ hybridization (ISH) for EBV-encoded viral RNA (EBER) was positive in the large cells. Scattered plasma cells were polyclonal by kappa and lambda ISH, with some IgG and IgG4 positive plasma cells noted (Fig. 3). These findings were consistent with CHL, mixed cellularity subtype, EBV associated.

Fig. 3.

a Lymph node excisional biopsy specimen (hematoxylin and eosin, × 100 magnification). b Lymph node excisional biopsy specimen with CD15 immunohistochemical staining. c Lymph node excisional biopsy specimen with CD30 immunohistochemical staining. c Lymph node excisional biopsy specimen with EBER (EBV associated RNA) staining

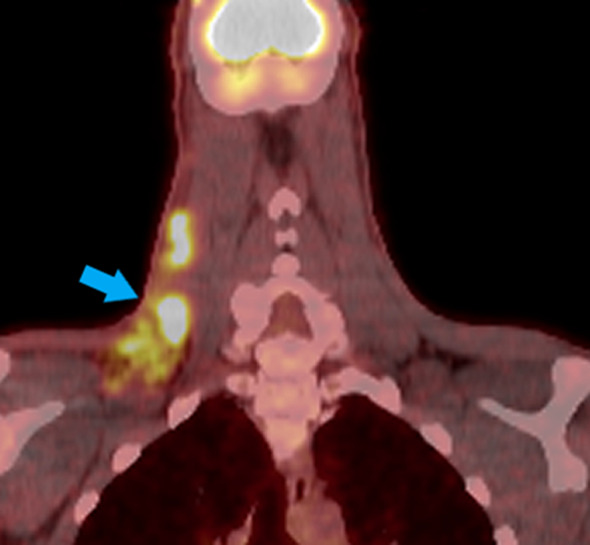

Based on imaging studies, the patient was designated as Ann-Arbor stage IIB disease (early unfavorable). The patient subsequently underwent chemotherapy with ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine) with involved-site radiotherapy and achieved complete treatment response two years after initial presentation. A positron emission tomography (PET) scan two months post-treatment showed no evidence of disease consistent with clinical remission (Fig. 4). Clinically, the patient continued to have pain in both hands, fatigue, and night sweats, but denied fever, chills or further unintentional weight loss.

Fig. 4.

PET/CT with arrow indicating enlarged lymphadenopathy

Discussion

EBV infection causing infective mononucleosis may mimic several lymphoproliferative disorders, including lymphoma, in the absence of underlying malignancy [2, 7]. Conversely, lymphoma may mimic a number of conditions, complicating the diagnosis. After extensive review of the literature, however, we were unable to find a case of lymphoma mimicking EBV infection, making the presentation described in this report unusual.

Tissue samples from enlarged lymph nodes of CAEBV typically show lymphoid hyperplasia without evidence of malignancy [11]. This presentation was consistent with the results of the first excisional biopsy, resulting in an initial diagnosis of CAEBV. Many factors contribute to the development of lymphoma and lymphoproliferative disorders in individuals with CAEBV, but the progression of the clinical course may depend on a balance of genetics, viral factors, and overall host immune status [9, 13]. It is unclear whether tissue from the initial biopsy was truly insufficient for diagnosis or if the patient developed lymphoma during this time. Patients with CAEBV are known to develop malignancies, including EBV-associated lymphoma, as the infection progresses [2, 11].

EBV is specifically associated with the development of several types of head and neck cancers including both Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma [14]. Both IM and CHL are diseases that present with scattered, atypical, EBV-positive cells and, because of these similarities, these entities may be mistaken for one another. CHL is distinguished from IM by the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells, the classic “owl-eye” binucleate cells with predominant nucleoli. However, these were not evident on the initial biopsies. Another clue to CHL is the presence of acute inflammatory cells like eosinophils, neutrophils, and plasma cells. This finding can help inform diagnosis and management in inconclusive cases without classic features. Evaluation of the excised lymph node six months later suggested CHL, evidenced by the presence of CD30, CD15, PAX5 (weak), OCT-2, and BOB1 staining with negativity for CD20 and CD45 [8] (Fig. 3). Notably, this specimen had CD10 + and BCL-6 + germinal centers, in contrast to the typical immunophenotypic profile of non-malignant EBV infection, and associated lymphoid infiltrates [7]. The histologic findings are important because although CHL is a B-cell lymphoma, it does not show kappa /lambda monotypia on flow cytometry. Rather, flow cytometry is often unremarkable, making the histopathologic diagnosis critical.

The symptoms of weight loss and night sweats over the course of the patient’s illness further supported an underlying lymphoproliferative process as CHL is known to cause generalized symptoms in just under half (41%) of cases along with painless, enlarged lymph nodes [16]. While this patient fully responded to chemotherapy and radiation, it is important to note the implications of a delayed diagnosis of lymphoma. Progression of the disease process confers increased morbidity and mortality as curative therapy and clinical remission are more challenging. In this particular case, the hypothesis of CAEBV progressing to lymphoma between biopsies is less likely as the advanced stage of lymphoma (Ann-Arbor IIB) together with B-symptomology suggests a long-standing disease process rather than a newly developed malignancy.

This case demonstrates the importance of multidisciplinary care as the clinical presentation, radiographic findings, and histologic examination together were necessary to achieve the correct diagnosis. Emphasis should be placed on appropriate sampling and tissue evaluation, as limited biopsy evaluation and sampling bias may obscure the accurate diagnosis and overall disease assessment.

Conclusions

We present a case of CHL masquerading as CAEBV in a patient with an enlarging, non-tender neck mass, weight loss, fever, and night sweats. Despite two initial fine needle biopsies that were negative for malignancy, a third excisional biopsy revealed CHL. The patient completed chemotherapy and involved-site radiotherapy two years following initial presentation with full treatment response. It is crucial to consider a diagnosis of lymphoma on the differential diagnosis for any enlarging neck mass or lymphadenopathy, despite negative results on limited biopsy specimens, especially with a documented history of EBV involvement of the lymphoid tissue.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Julie Teruya-Feldstein, Dr. Adolfo Firpo-Betancourt and the Department of Pathology, Molecular & Cell-Based Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital for their assistance in obtaining and reviewing slides.

Funding

The authors have no funding, financial relationships.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Arai A, et al. Clinical features of adult-onset chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection: a retrospective analysis. Int J Hematol. 2011;93(5):602–9. doi: 10.1007/s12185-011-0831-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auerbach A, Aguilera NS. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated lymphoid lesions of the head and neck. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2015;32(1):12–22. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bollard CM, Cohen JI. How I treat T-cell chronic active Epstein-Barr virus disease. Blood. 2018;131(26):2899–905. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-03-785931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen JI. Epstein-Barr virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(7):481–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008173430707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimura H, Cohen JI. Chronic active Epstein-Barr virus disease. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1867. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimura H. Prognostic factors for chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(4):527–533. doi: 10.1086/367988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Louissaint A, Jr, et al. Infectious mononucleosis mimicking lymphoma: distinguishing morphological and immunophenotypic features. Mod Pathol. 2012;25(8):1149–59. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathas S, Hartmann S, Küppers R. Hodgkin lymphoma: pathology and biology. Semin Hematol. 2016;53(3):139–47. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAulay KA, Jarrett RF. Human leukocyte antigens and genetic susceptibility to lymphoma. Tissue Antigens. 2015;86(2):98–113. doi: 10.1111/tan.12604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okano M. Severe chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4(1):129–35. doi: 10.1128/CMR.4.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okano M. Overview and problematic standpoints of severe chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection syndrome. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;44(3):273–82. doi: 10.1016/S1040-8428(02)00118-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okano M. Acute or chronic life-threatening diseases associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. Am J Med Sci. 2012;343(6):483–9. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318236e02d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park S, Ko YH. Epstein-Barr virus-associated T/natural killer-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. J Dermatol. 2014;41(1):29–39. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prabhu SR, Wilson DF. Evidence of Epstein-Barr virus association with head and neck cancers: a review. J Can Dent Assoc. 2016;82:2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sawada A, Inoue M, Kawa K. How we treat chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection. Int J Hematol. 2017;105(4):406–18. doi: 10.1007/s12185-017-2192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weber AL, Rahemtullah A, Ferry JA. Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the head and neck: clinical, pathologic, and imaging evaluation. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2003;13(3):371–92. doi: 10.1016/S1052-5149(03)00039-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]