Abstract

Long standing, asymptomatic, well-demarcated erythema of the hard palate with a histopathological psoriasiform pattern comprises a challenging diagnosis. We present a series of patients with such clinical and histological findings and discuss the possible diagnoses. We collected all patients with palatal erythematous lesions that had well-documented clinical examination. Excluded were patients with definitive diagnosis of oral infections (e.g. candidiasis), neoplastic/pre-neoplastic lesions, auto-immune diseases, reactive lesions, blood disorders and vascular malformations. Thirteen patients (six females, seven males, age range 11–56 years) were included. Histopathologically, a psoriasiform pattern was observed in all biopsied lesions. One patient was diagnosed with hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia (HMD) and four with cutaneous psoriasis. The remaining eight patients were otherwise healthy. A combination of persistent, asymptomatic palatal erythematous lesion with psoriasis-like histopathology may represent an oral manifestation of HMD or psoriasis, concomitant to extra-oral features. In lack of any known medical background, the term "oral psoriasiform mucositis" is suggested.

Keywords: Oral psoriasiform mucositis, Hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia, Oral psoriasis

Introduction

A long standing erythema manifested mainly or solely on the anterior hard palate, may be related to various oral pathological entities, such as chronic atrophic candidiasis, hematinic deficiencies, reactive (e.g. due to upper denture or removable orthodontic appliance) or immune-related conditions and neoplastic processes [1, 2]. An accurate diagnosis can be achieved by thorough history, intra- and extra-oral clinical co-manifestations, histopathological examination and additional laboratory tests.

We present a series of dentulous patients that share this clinical manifestation combined with histopathologic finding of psoriasiform epithelial pattern and discuss their possible heterogeneous etiologies, as we believe that these are un-recognized and under-reported lesions.

Patients and Methods

This retrospective study included patients that presented with erythematous palatal mucosa after excluding other etiologies, such as oral mucosal infections (e.g. oral candidiasis, herpetic stomatitis), reactive lesion (e.g. denture stomatitis), immune-related conditions (e.g. irritant or allergic contact stomatitis, lichenoid contact reaction, erythema multiforme), non-psoriatic autoimmune diseases (e.g. oral lichen planus, mucous membrane pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris), hematological disorders, vascular malformations, neoplastic/pre-neoplastic processes or any other defined pathological entity.

Parameters of demographical data, medical background and clinical presentation (intra- and extra-oral) as well as the treatment that had been given for the oral lesions, were retrieved from the patients' files.

Results

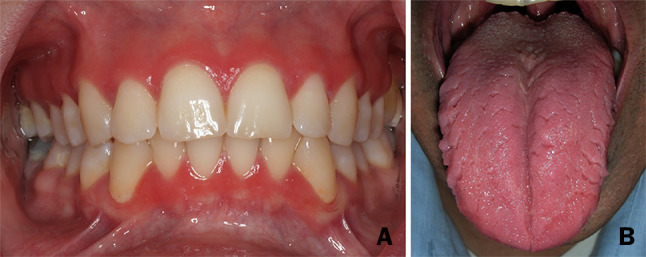

We have retrieved a total of 13 patients (six females and seven males; aged 11 to 56 years at diagnosis) who fulfilled the above criteria. The patient characteristics and their clinical features, including intra- and extra-oral manifestations, are presented in Table 1 and in Figs. 1, 2 and 3. All patients presented with a remarkable, well-demarcated symmetrical fiery-red erythema on the palatal mucosa, especially in the pre-maxilla (area of the rugae) (Fig. 1). Focal fiery-red hyperplastic gingivae in the upper jaw were recorded in 3 patients (#7, #8 and #13; Fig. 2a). Fissured tongue was noticed in 6 cases (#2, #3, #4, #5, #8 and #13; Fig. 2b), and geographic tongue in 4 patients (#2, #3, #5 and #11; Fig. 2b). Involvement of the lip commissure, presenting as angular cheilitis, was seen in patient #8.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of our patients

| Case no. | Gender | Age at diagnosis (years) | Health status including dermal conditions | Oral symptoms | Involved intraoral location of erythematous lesions | Other tongue conditions | Final diagnosis of the palatal lesion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior hard palate | Gingiva | Other locations | |||||||

| 1 | F | 56 | Otherwise healthy | Transient mild burning sensation (palate) | + | – | – | – | Oral psoriasiform mucositis |

| 2 | F | 49 | Otherwise healthy | – | + | – | – | GT, FT | Oral psoriasiform mucositis |

| 3 | M | 49 | Psoriasis, thyroiditis, hemoptysis | – | + | – | – | GT, FT | Psoriasis |

| 4 | M | 46 | Otherwise healthy | – | + | – | – | FT | Oral psoriasiform mucositis |

| 5 | M | 40 | G6PD deficiency, constipation | – | + | – | – | GT, FT | Oral psoriasiform mucositis |

| 6 | M | 24 | Psoriasis | Transient mild burning sensation (palate) | + | – | – | – | Psoriasis |

| 7 | F | 21 | Otherwise healthy | – | + | + | – | – | Oral psoriasiform mucositis |

| 8 | F | 17 | Allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis | – | + | + | Dorsal tongue, lip commissure | FT | Oral psoriasiform mucositis |

| 9 | M | 12 | Short stature, alopecia, atopic dermatitis, corneal abscess | – | + | – | – | – | Hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia |

| 10 | M | 46 | Psoriasis | – | + | – | – | – | Psoriasis |

| 11 | M | 11 | Otherwise healthy | – | + | – | – | GT | Oral psoriasiform mucositis |

| 12* | F | 53 | Psoriasis | – | + | – | – | – | Psoriasis |

| 13* | F | 19 | Ichthyosis vulgaris | Transient itching (palate) | + | + | Tongue | FT | Oral psoriasiform mucositis |

F female, M male, yr. years, G6PD glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, FT fissured tongue, GT geographic tongue

*Patients #12 and #13 are mother and daughter, and does not refer to any statistical significance

Fig. 1.

Palatal erythematous lesions—the same clinical manifestation shared by a group of patients with a different health status. a Patient #1 who was completely healthy. b Patient #3 who was diagnosed with cutaneous psoriasis. c Patient #9 who presented additional systemic abnormalities compatible with hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia

Fig. 2.

Oral (non-palatal) lesions/conditions. a Gingival involvement in patient #13. b Tongue involvement: geographic and fissured tongue in patient #3

Fig. 3.

Extra-oral lesions/conditions. Patient #10 presenting cutaneous psoriatic lesions (a); and patient #9 with alopecia (b)

None of our patients reported a familial history of hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia (HMD). Eight patients presented dermal conditions, such as psoriasis (#3, #6, #10, and #12; Fig. 3a), atopic dermatitis (#8 and #9), alopecia (#9; Fig. 3b) and ichthyosis vulgaris (#13). The patients with psoriasis were reassessed by an experienced dermatologist (A.B.) who had confirmed this diagnosis. Five patients were otherwise healthy without any diagnosed medical condition (#1, #2, #4, #7 and #11).

Two patients used removable partial dentures (removed at night; patients #5 and #10) and one had an orthodontic retainer (only at night; #8). In contrast to denture stomatitis, no correlation was noticed between the location and shape of the appliances and the oral lesions.

Ten patients were completely asymptomatic. Complaints of a general mild burning sensation were reported in 2 patients (#1 and #6) and one patient complained of itching (#13); however, the burning and itching sensations spontaneously resolved during follow-up while the oral manifestation remained completely unchanged.

Except two (#7 and #12), all patients were tentatively diagnosed with oral candidiasis (clinically only, with no laboratory examination) and nine of them (#1, #2, #3, #4, #5, #6, #8, #10 and #13) were treated with topical antifungal agents that barely achieved a partial improvement in the appearance of the palatal lesions. Patient #7 was initially suspected for erythema multiforme and was treated with topical corticosteroids that were ineffective. Laboratory tests revealed nutritional deficiencies in patients #3, #4, #5 and #6 that consequently were treated by adequate supplements; no clinical improvement was noticed in follow-up visits.

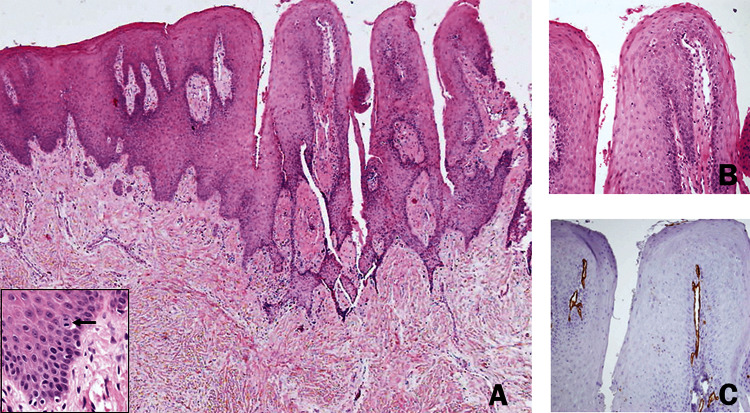

In all patients, except one (#11), an incisional biopsy was taken from the palatal lesion. Microscopically, all the biopsied lesions demonstrated findings compatible with a psoriasiform pattern (Fig. 4). Elongated rete ridges usually of an even length, and concomitant high and rather superficial tips of the connective tissue were observed in all specimens. Occasionally, mitotic figures were observed within the oral epithelium, some of them above the basal layer. In one biopsy, a few neutrophils were seen within the keratin layer, reminiscent of the pattern seen in Monroe abscess. The superficial extensions of the connective tissue carried dilated and torturous blood vessels. A light diffuse chronic inflammatory response was usually present within the connective tissue. The rich vascularity of the connective tissue tips has been highlighted using immunohistochemistry with anti CD31 antibody (Fig. 4c; Abcam, Cambridge, UK; ab124432).

Fig. 4.

Oral psoriasiform mucositis: characteristic microscopic findings of the palatal lesions. a The oral lining epithelium shows a nodular outline. There is remarkable acanthosis with downward elongation of the rete ridges. Tips of the connective tissue papillae extend towards the surface and are lined by a relatively thinned epithelium. Suprabasilar mitotic figures were occasionally seen (inset). b The connective tissue tips contain prominent, tortuous blood vessels. c The rich and superficial vascularity was highlighted by CD31 immunostain

Discussion

Erythematous lesions of the oral cavity may be the result of either epithelial and/or subepithelial alterations, usually caused by inflammation, variations in vascularity or neoplastic/pre-neoplastic changes. The diagnosis can be challenging when these lesions are present almost solely on the anterior hard palate (sometimes with involvement of the adjacent gingiva) in a practically asymptomatic and chronic manner. In the present study we report 13 such patients. Oral candidiasis was the main attempted clinical diagnosis, but erythema multiforme, hematinic deficiencies, oral lichen planus and erythroplakia were also included in the differential diagnosis. However, given the histopathological results, the final diagnoses were restricted to HMD and psoriasis involving the oral mucosae.

HMD is a rare genetic disorder that was first described in by Witkop et al. [3, 4] and from then, only several dozens of cases were reported [5–8]. This condition assumedly results from structural irregularities in the intercellular adhesion complexes (i.e. desmosomes and gap junctions) [3, 4]. The disease is considered as autosomal dominantly inherited, although sporadic cases have been described. However, the offender gene has not yet been identified, and therefore, no definitive test can be performed to confirm or rule out the diagnosis of HMD [5, 6]. Recently several authors have suggested that the existence of the triad of non-scarring alopecia, well-demarcated erythema of oral mucosa and psoriasiform perineal rash should strongly suggest the diagnosis of this disorder [6, 7].

Following a comprehensive analysis of the well documented HMD cases in which the oral cavity has been inspected, erythematous lesions were inevitably observed on the mucosa of the hard palate [3–8] and histopathologic psoriasiform patterns were found in the dermal and/or mucosal biopsies in most of the cases [5, 6, 8]. These lesions were identical to those detected in our patients at both clinical and microscopical levels. However, while in the HMD cases alopecia, dermal and ocular pathologies were always present and genital and pulmonary involvements were frequently reported, only one of our 13 patients, a 12-year-old, actually presented extra-oral manifestations that could conform to the diagnosis of HMD. Apart from the characteristic oral lesions, no additional similarities were found between our other 12 patients and the reported HMD cases.

Four of our patients had cutaneous psoriasis. Currently, there is no consensus whether the oral cavity is actually involved by psoriasis and if so, what are the exact oral manifestations of this condition [9, 10]. Geographic and fissured tongue are often associated with psoriasis [9, 11–14]. Geographic tongue, the most common manifestation of erythema migrans, which occasionally can involve extra-lingual locations, appears clinically as wax and wane atrophic lesions bordered by slightly elevated, thin, white hyperkeratotic margins [15]. In addition, other mucosal expressions have been described in psoriatic patients, including diffuse intense mucosal erythema and a mixture of ulcerative, vesicular, pustular and indurated lesions [16, 17]. These lesions commonly manifest on the tongue and less frequently on the hard palate, buccal mucosa and gingiva [18, 19]. Moreover, the accurate incidence of psoriatic oral lesions is also questionable as a consequence of the overlap of histological features between cases of true oral psoriasis and other oral conditions, such as geographic tongue [9, 20]. Given that the palatal lesions noted in four of our patients with psoriasis demonstrated histopathologically a psoriasiform pattern, the possibility that these oral lesions could be attributed to the cutaneous disease has to be taken into consideration.

Eight of our patients did not manifest any extra-oral lesions that could be attributed to HMD and psoriasis. Therefore, we may raise the possibility that at least part of these patients could represent a localized/limited form of non-diagnosed HMD, but unfortunately, due to a lack of a definite identification of the genetic alterations in HMD, we currently cannot accurately confirm or reject this assumption. In addition, we cannot exclude the possibility that at least some of these patients, who were not previously diagnosed with psoriasis, could be considered as having oral psoriasis. To support this, is the finding that these patients demonstrated a high frequency of fissured tongue (62.5%) and geographic tongue (37.5%), while the estimated prevalence of fissured tongue in the general population is only 2–5% and of geographic tongue is 1–3% [20, 21]. Still, we cannot exclude that the presence of palatal erythema and fissured tongue/geographic tongue in our patients was incidental. To this moment, only a few cases of oral psoriasis that exclusively affect the oral mucosa were reported in the English literature [11, 22]. Reis et al. reported a 35-years-old female with erythematous patches on the hard and soft palate and diffuse erythema on the upper gingival mucosa. No other lesions were noticed in other mucosal areas or skin and she was otherwise healthy [23]. Histological examination was consistent with a psoriasiform lesion. According to those authors, in the absence of sufficient diagnostic criteria this patient should not be diagnosed with oral psoriasis and the term oral psoriasiform mucositis (OPM) was suggested to be much more appropriate for her diagnosis [23]. In light of this, OPM could be applied to eight of our patients that could not be definitively diagnosed with either HMD or psoriasis.

The inter-relations between the clinical and histopathological features of the palatal erythema and the range of possible diagnoses are illustrated in Fig. 5. As of this moment, a long standing diffuse erythema mainly or solely manifested on the palate with a histopathologic psoriasiform pattern may represent (1) HMD in the rare cases in which the pathognomonic extra-oral manifestations of this systemic condition are present, (2) an oral manifestation of psoriasis in patients diagnosed with cutaneous psoriasis, (3) less likely, a focal or restricted form of HMD or psoriasis, and (4) a distinctive oral condition of OPM, that although inherently benign, its true nature remains to be clarified.

Fig. 5.

Illustrative relationship between oral psoriasiform mucositis and other conditions presenting with the same oral manifestation

Compliance with Ethical Standard

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of Tel-Aviv University and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration in its later amendments, which did not require informed consent.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ayelet Zlotogorski Hurvitz and Yehuda Zadik have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Scully C, Felix DH. Oral medicine-update for the dental practitioner. 6. Red and pigmented lesions. Br Dent J. 2005;199:639–645. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4813017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reichart PA, Philipsen HP. Oral erythroplakia: a review. Oral Oncol. 2005;41:551–561. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witkop CJ, Jr., White JG, Sauk JJ, Jr., King RA. Clinical, histologic, cytologic, and ultrastructural characteristics of the oral lesions from hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia: a disease of gap junction and desmosome formation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1978;46:645–657. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(78)90461-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Witkop CJ, Jr, White JG, King RA, Dahl MV, Young WG, Sauk JJ., Jr Hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia: a disease apparently of desmosome and gap junction formation. Am J Hum Genet. 1979;31:414–427. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leithauser LA, Mutasim DF. Hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia: unique histopathological findings in skin lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:431–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2011.01857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boralevi F, Haftek M, Vabres P, Lepreux S, Goizet C, Leaute-Labreze C, et al. Hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia: clinical, ultrastructural and genetic study of eight patients and literature review. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:310–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halawa M, Abu-Hasan MN, ElMallah MK. Hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia and severe respiratory distress. Respir Med Case Rep. 2015;15:27–29. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kulkarni T, de Andrade J, Zhou Y, Luckhardt T, Thannickal VJ. Alveolar epithelial disintegrity in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2016;311:L185–L191. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00115.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu J-F, Kaminski MJ, Pulitzer DR, Hu J, Thomas HF. Psoriasis: pathophysiology and oral manifestations. Oral Dis. 1996;2:135–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1996.tb00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yesudian PD, Chalmers RJ, Warren RB, Griffiths CE. In search of oral psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2012;304:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00403-011-1175-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Picciani B, Silva-Junior G, Carneiro S, Sampaio A, Goldemberg D, Oliveira J, Porto L, Dias E. Geographic stomatitis: an oral manifestation of psoriasis? J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:113–116. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2012.1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernández-Pérez F, Jaimes-Aveldañez A, Urquizo-Ruvalcaba Mde L, Díaz-Barcelot M, Irigoyen-Camacho ME, Vega-Memije ME, Mosqueda-Taylor A. Prevalence of oral lesions in patients with psoriasis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:E703–E708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Germi L, De Giorgi V, Bergamo F, Niccoli MC, Kokelj F, Simonacci M, Satriano RA, Priano L, Massone C, Pigatto P, Filosa G, De Bitonto A, Fornasa CV. Psoriasis and oral lesions: multicentric study of Oral Mucosa Diseases Italian Group (GIPMO) Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawson TA. Tongue lesions in generalized pustular psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1974;91:419–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1974.tb13080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zadik Y, Drucker S, Pallmon S. Migratory stomatitis (ectopic geographic tongue) on the floor of the mouth. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:459–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA. Oral psoriasis: an overlooked enigma. Dermatology. 2016;232:319–325. doi: 10.1159/000444850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pindborg JJ. Atlas of diseases of the oral mucosa. 4. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pietrzak D, Pietrzak A, Krasowska D, Borzęcki A, Franciszkiewicz-Pietrzak K, Polkowska-Pruszyńska B, Baranowska M, Reich K. Digestive system in psoriasis: an update. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017;309:679–693. doi: 10.1007/s00403-017-1775-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brooks JK, Kleinman JW, Modly CE, Basile JR. Resolution of psoriatic lesions on the gingiva and hard palate following administration of adalimumab for cutaneous psoriasis. Cutis. 2017;99:139–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Migliari DA, Penha SS, Marques MM, Matthews RW. Considerations on the diagnosis of oral psoriasis a case report. Med Oral. 2004;9:300–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Chi AC. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. 4. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2016. pp. 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Younai SF, Phelan JA. Oral mucositis with features of psoriasis: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84:61–67. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(97)90297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reis V, Artico G, Seo J, Bruno I, Hirota S, Lemos C, Martins M, Migliari D. Psoriasiform mucositis on the gingival and palatal mucosae treated with retinoic-acid mouthwash. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:113–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]