Highlights

-

•

Shorter treatment regimen for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.

-

•

Effect of companion drug resistance on adverse outcomes.

-

•

Gatifloxacin and isoniazid minimum inhibitory concentration.

-

•

Whole-genome sequencing.

-

•

Non-eligibility for the regimen not associated with adverse outcome.

-

•

Exclusions justified only in the case of fluoroquinolone or kanamycin resistance.

Keywords: Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, Shorter treatment regimen, Antimicrobial resistance, Fluoroquinolones, High-dose isoniazid, Whole-genome sequencing

Abstract

Objectives

We investigated whether companion drug resistance was associated with adverse outcomes of the shorter multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) treatment regimen in Bangladesh after adjustment for fluoroquinolone resistance.

Methods

MDR-TB/rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis patients registered for treatment with a standardized gatifloxacin-based shorter MDR-TB treatment regimen were selected for the study. Drug resistance was determined by the proportion method, gatifloxacin and isoniazid minimum inhibitory concentration testing for selected isolates, and whole-genome sequencing.

Results

Low-level fluoroquinolone resistance and high-level fluoroquinolone resistance were the most important predictors of adverse outcomes, with pyrazinamide resistance having a significant yet lower impact. In patients with fluoroquinolone-/second-line-injectable-susceptible tuberculosis, non-eligibility for the shorter MDR-TB treatment regimen (initial resistance to pyrazinamide, ethionamide, or ethambutol) was not associated with adverse outcome (adjusted odds ratio 1.01; 95% confidence interval 0.4–2.8). Kanamycin resistance was uncommon (1.3%). Increasing levels of resistance to isoniazid predicted treatment failure, also in a subgroup of patients with high-level fluoroquinolone-resistant tuberculosis.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that resistance to companion drugs in the shorter MDR-TB treatment regimen, except kanamycin resistance, is of no clinical importance as long as fluoroquinolone susceptibility is preserved. Hence, contrary to current WHO guidelines, exclusions to the standard regimen are justified only in the case of fluoroquinolone resistance. and possibly kanamycin resistance.

Introduction

Ideally, a tuberculosis (TB) treatment regimen includes a core drug that drives the efficacy of the regimen, and companion drugs with either bactericidal or sterilizing activity (Van Deun et al., 2018). On the basis of these principles, the so-called shorter regimen for the treatment of multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) was developed in Bangladesh two decades ago (Aung et al., 2014, Van Deun et al., 2010). It used later-generation fluoroquinolones (either gatifloxacin or levofloxacin) as the core drug and kanamycin as the main drug protecting against acquisition of resistance to the core drug. Companion drugs were included to help prevent acquired resistance to fluoroquinolone and kanamycin (Van Deun et al., 2018). Prothionamide was included because it has also bactericidal activity, and pyrazinamide and clofazimine were included because they help in sterilization. Isoniazid was expected to often have some remaining activity, contributing to the effectiveness of the regimen to a highly variable extent. The same is true for the bacteriostatic ethambutol, to which most MDR strains showed resistance at that time (Van Deun et al., 2018).

The shorter treatment regimen has since been successfully implemented in many countries worldwide. Resistance to fluoroquinolones has been found to be the major predictor of adverse treatment outcome (Rigouts et al., 2016, Trébucq et al., 2019, Van Deun et al., 2019). The importance of resistance to the other drugs in the regimen is insufficiently understood (Trébucq et al., 2019). Originally designed as a standardized regimen in a low-resource setting, the shorter treatment regimen was administered without prior drug susceptibility testing (DST). Full susceptibility to all companion drugs was not counted on, because their individual activity was not considered essential for high success rates. Moreover, the regimen was considered as part of a cascade of regimens, with a next-level core drug regimen for retreatment of the expected few failure and relapse cases (Van Deun et al., 2018). Nevertheless, current WHO guidelines for the treatment of MDR-TB recommend the use of resistance to any of the drugs in the regimen, except isoniazid, as an exclusion criterion for the shorter MDR-TB treatment regimen (WHO, 2019c).

Recently published extensive data on companion drug resistance suggest that the effect of resistance to companion drugs in the shorter MDR-TB treatment regimen on outcome is rather limited (Piubello et al., 2020). However, in this cohort, very few patients had an adverse bacteriological outcome (12/249; with eight failures and four relapses), limiting the estimation of predictors of poor outcome. Moreover, kanamycin resistance is quite rare in most settings where the regimen has been studied, restricting analyses of its association with adverse outcome (Trébucq et al., 2019). A recent individual patient data meta-analysis found that, except in low-income settings, kanamycin worsened MDR-TB treatment outcomes, which led to the WHO recommendation to stop using kanamycin (Ahmad et al., 2018, WHO, 2019c). Unfortunately, the meta-analysis neglected to check the effectiveness of injectables for prevention of acquired resistance to the core drug. Moreover, the adverse outcomes with use of kanamycin were from high-income settings only, and these results contradicted those of the previous meta-analysis by the same group that found greater survival with longer use of injectables, leading to the 2014 WHO guidelines recommending injectables for at least the first 8 months (Ahuja et al., 2012, WHO, 2014). Most likely this has led to excessively frequent ototoxicity, which is inevitable with prolonged use of these drugs, that has provoked the sudden aversion to any use of these standard TB drugs and their replacement by a new core drug with still many unknowns; that is, bedaquiline (WHO, 2019c).

A study on the implementation of the shorter MDR-TB treatment regimen in nine African countries found that isoniazid susceptibility was associated with a significantly lower risk of bacteriological failure. Since testing for isoniazid resistance is still difficult and often not done, this is another reason to use isoniazid indiscriminately for all rifampicin-resistant TB (RR-TB; Schwœbel et al., 2020, Trébucq et al., 2018). Resistance also to isoniazid (MDR-TB) is highly prevalent in RR-TB isolates (WHO, 2019a), but the frequency of the highest level of resistance, conferred by double mutations in katG and inhA (Ghodousi et al., 2019, Lempens et al., 2018), is low (<5% in most settings) (Seifert et al., 2015), and the association between different levels of resistance to the drug and treatment outcome remains unclear.

In this study, we investigated a large cohort of MDR-TB patients from Bangladesh to assess whether resistance to companion drugs is associated with adverse outcome of the shorter MDR-TB treatment regimen after adjustment for fluoroquinolone resistance. Moreover, whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data for this cohort enabled us to look into drug resistance in greater detail.

Materials and methods

Study setting

The study was conducted in the Damien Foundation MDR-TB project area in Bangladesh, which spans 13 of 64 districts of the country. In 2018, the incidence rate of TB in Bangladesh was 221 cases per 100,000, with HIV prevalence in incident TB patients of 0.20%. The incidence rate of MDR-TB/RR-TB was 3.7 cases per 100,000 (WHO, 2019a).

Study design

This was a retrospective cohort study.

Study population

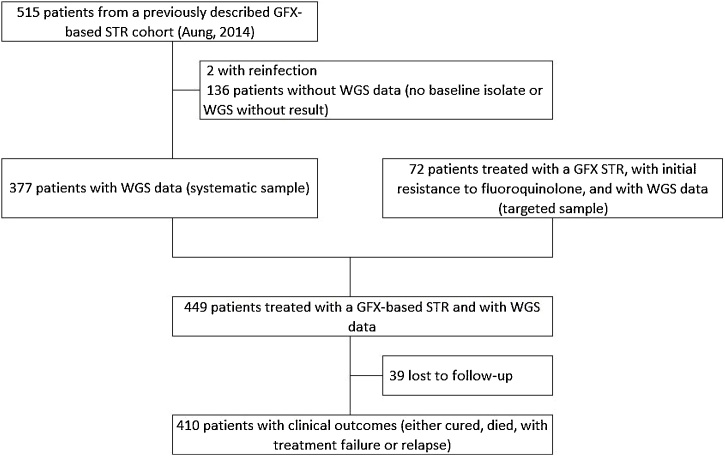

Between March 2005 and March 2015, 943 gatifloxacin-based shorter MDR-TB treatment regimen episodes for MDR-TB/RR-TB patients were registered. Besides the systematic sample including patients of the previously described Bangladesh MDR-TB cohort (Aung et al., 2014), patients with fluoroquinolone-resistant MDR/RR-TB were selected to specifically study the effect of resistance to companion drugs on treatment outcome (i.e. targeted sample) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the number of patients included in the analysis. Patients were registered for treatment in the Damien Foundation multidrug-resistant tuberculosis project area in Bangladesh between March 2005 and March 2015. For the analysis in Table 5, only patients in the cohort described by Aung et al. (2014) with a clinical outcome (342 patients = 377 patients −35 patients lost to follow-up) were included. GFX, gatifloxacin; STR, shorter multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment regimen; WGS, whole-genome sequencing.

Treatment

Patients were treated with the shorter MDR-TB treatment regimen consisting of high-dose gatifloxacin (up to 800 mg for those weighing more than 50 kg), clofazimine, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide for 9–11 months, supplemented with high-dose isoniazid (10 mg/kg), kanamycin, and prothionamide during the intensive phase of 4–6 months (the intensive phase was extended by 1 or 2 months if there was no smear conversion after 4 or 5 months). Further treatment details as well as treatment outcome definitions used have been described previously (Aung et al., 2014, Van Deun et al., 2010). Reinfection was distinguished from relapse by spoligotype analysis, and by assessment of mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit variable number tandem repeats if spoligotypes were identical.

Drug susceptibility testing

A detailed description of the final classification rules for drug resistance (level) per drug is given in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the variables included in the study, stratified by initial fluoroquinolone (FQ) resistance.

| Total |

Initial FQ resistance |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FQ S |

FQ R low |

FQ R high |

||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| 449 | 352 | 26 | 71 | |||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 133 | 29.6 | 101 | 28.7 | 7 | 26.9 | 25 | 35.2 |

| Male | 316 | 70.4 | 251 | 71.3 | 19 | 73.1 | 46 | 64.8 |

| Age group (years) | ||||||||

| 10 to <20 | 47 | 10.5 | 35 | 9.9 | 4 | 15.4 | 8 | 11.3 |

| 20 to <30 | 152 | 33.9 | 108 | 30.7 | 10 | 38.5 | 34 | 47.9 |

| 30 to <40 | 104 | 23.2 | 92 | 26.1 | 4 | 15.4 | 8 | 11.3 |

| 40 to <50 | 75 | 16.7 | 59 | 16.8 | 6 | 23.1 | 10 | 14.1 |

| 50 to <60 | 45 | 10.0 | 37 | 10.5 | 1 | 3.8 | 7 | 9.9 |

| ≥60 | 26 | 5.8 | 21 | 6.0 | 1 | 3.8 | 4 | 5.6 |

| Initial KAN resistance | ||||||||

| No | 443 | 98.7 | 352 | 100 | 25 | 96.2 | 66 | 93.0 |

| Yes | 6 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.8 | 5 | 7.0 |

| Initial INH resistance (gDST) | ||||||||

| S | 23 | 5.1 | 21 | 6.0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.8 |

| R low | 23 | 5.1 | 19 | 5.4 | 1 | 3.8 | 3 | 4.2 |

| R moderate | 358 | 79.7 | 281 | 79.8 | 21 | 80.8 | 56 | 78.9 |

| R high | 45 | 10.0 | 31 | 8.8 | 4 | 15.4 | 10 | 14.1 |

| Initial INH resistance (pDST) | ||||||||

| S | 5 | 1.1 | 5 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| R low | 17 | 3.8 | 15 | 4.3 | 1 | 3.8 | 1 | 1.4 |

| R moderate | 48 | 10.7 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 11.5 | 45 | 63.4 |

| R high | 18 | 4.0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7.7 | 16 | 22.5 |

| Unknown | 361 | 80.4 | 332 | 94.3 | 20 | 76.9 | 9 | 12.7 |

| Initial INH resistance (gDST and pDST) | ||||||||

| S | 4 | 0.9 | 4 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| R low | 17 | 3.8 | 15 | 4.3 | 1 | 3.8 | 1 | 1.4 |

| R moderate | 48 | 10.7 | 1 | 0.3 | 3 | 11.5 | 44 | 62.0 |

| R high | 19 | 4.2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7.7 | 17 | 23.9 |

| Unknown | 361 | 80.4 | 332 | 94.3 | 20 | 76.9 | 9 | 12.7 |

| Initial EMB resistance | ||||||||

| No | 148 | 33.0 | 129 | 36.6 | 4 | 15.4 | 15 | 21.1 |

| Yes | 301 | 67.0 | 223 | 63.4 | 22 | 84.6 | 56 | 78.9 |

| Initial PZA resistance | ||||||||

| No | 302 | 67.3 | 254 | 72.2 | 13 | 50.0 | 35 | 49.3 |

| Yes | 147 | 32.7 | 98 | 27.8 | 13 | 50.0 | 36 | 50.7 |

| Initial ETH resistance | ||||||||

| No | 344 | 76.6 | 274 | 77.8 | 17 | 65.4 | 53 | 74.6 |

| Yes | 105 | 23.4 | 78 | 22.2 | 9 | 34.6 | 18 | 25.4 |

| Initial CFZ resistance | ||||||||

| No | 449 | 352 | 26 | 71 | ||||

| Outcomes | ||||||||

| Cure | 344 | 76.6 | 292 | 83.0 | 20 | 76.9 | 32 | 45.1 |

| Completion | 12 | 2.7 | 10 | 2.8 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.8 |

| FL | 19 | 4.2 | 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 7.7 | 16 | 22.5 |

| RL | 8 | 1.8 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7.7 | 6 | 8.5 |

| Death | 27 | 6.0 | 20 | 5.7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 9.9 |

| LTFU | 39 | 8.7 | 29 | 8.2 | 2 | 7.7 | 8 | 11.3 |

| Programmatic effectiveness | ||||||||

| Success | 356 | 79.3 | 302 | 85.8 | 20 | 76.9 | 34 | 47.9 |

| Adverse outcome (death, LTFU, FL, or RL) | 93 | 20.7 | 50 | 14.2 | 6 | 23.1 | 37 | 52.1 |

| Clinical effectiveness | ||||||||

| Success | 356 | 86.8 | 302 | 93.5 | 20 | 83.3 | 34 | 54.0 |

| Adverse outcome (death, FL, or RL) | 54 | 13.2 | 21 | 6.5 | 4 | 16.7 | 29 | 46.0 |

| Sample | ||||||||

| Systematic | 377 | 84.0 | 352 | 100 | 13 | 50.0 | 12 | 16.9 |

| Targeted | 72 | 16.0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 50.0 | 59 | 83.1 |

CFZ, clofazimine; EMB, ethambutol; ETH, ethionamide; FL, failure; gDST, genotypic drug susceptibility testing; high, high level; INH, isoniazid; KAN, kanamycin; LTFU, lost to follow-up; low, low level; moderate, moderate level; pDST, phenotypic drug susceptibility testing; PZA, pyrazinamide; R, resistant; RL, relapse; S, susceptible.

Phenotypic drug resistance was determined by the proportion method on Löwenstein–Jensen (LJ) medium (isoniazid 0.2, 1.0, and 5.0 mg/L, ethambutol 2 mg/L) and Middlebrook 7H11 agar (ofloxacin 2.0 and 8.0 mg/L, kanamycin 6.0 mg/L, ethionamide 10.0 mg/L). In addition, gatifloxacin minimum inhibitory concentration (0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 8.0, and 16.0 mg/L on LJ medium) was determined for isolates with resistance to ofloxacin at 2.0 mg/L, and isoniazid minimum inhibitory concentration (1.6, 3.2, 6.4, 12.8, 19.2, and 25.6 mg/L on LJ medium) was determined for isolates with high-level resistance to ofloxacin at 8.0 mg/L.

Genotypic resistance was determined by WGS. A subset of isolates (n = 47) was included in our earlier publication on the association between genotypic and phenotypic isoniazid resistance, and their WGS was described there (Lempens et al., 2018). For the remaining samples, genomic DNA was extracted by a combined enzymatic and mechanical extraction procedure (Lempens et al., 2018). WGS was done at the Translational Genomics Research Institute through the ReSeqTB sequencing platform (Starks et al., 2015). Microbial classification of the reads was done with Centrifuge (Kim et al., 2016) and non-Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) reads were removed. Isolates were marked as contaminated and were subsequently excluded if the percentage of non-MTB reads was greater than 10%. The MTBseq pipeline was used for quality control of the MTB reads, and isolates failing quality control (i.e. < 90% coverage of the reference genome or average sequencing depth <30×) were excluded (Kohl et al., 2018). Read trimming and mapping as well as variant calling and annotation were done with command line version 2.8.12 of TBProfiler (Coll et al., 2015, Phelan et al., 2019). Annotated variants were reported if found at any frequency in the isolate (i.e. minority populations conferring heteroresistance) and if present in the literature-based TBProfiler library database (https://github.com/jodyphelan/tbdb) accessed on 15 July 2020. Genomic variants associated with drug resistance having a sequencing depth below the default threshold of 10× but greater than 1× were included in the analysis. They were frequently found at certain common drug resistance positions, and for drugs with additional susceptibility information, their presence was supported by Sanger sequencing, line probe assay, and/or phenotypic DST (pDST) results.

Data availability

WGS reads are available in the European Nucleotide Archive (PRJEB39569). Variables included in the analysis are provided in Supplementary Table 2. Moreover, WGS reads, as well as pDST and clinical data, are included in the ReSeqTB data platform and are accessible on registration at https://platform.reseqtb.org/.

Table 2.

Correlation between genotypic and phenotypic isoniazid (INH) susceptibility testing in 88 patients with data available for both methods.

| Total | Phentotypic DST level of resistance |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | Low | Moderate | High | No data | ||

| Susceptible on gDST | ||||||

| Wild type | 21 | 4 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| ahpC 52C > T | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| ahpC 81C > T | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Low-level resistance on gDST | ||||||

| fabG1 15C > T | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| fabG1 15C > Ta | 13 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| fabG1 17 G > T | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| fabG1 8 T > C | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| InhA Ile194Thra | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| InhA Ile21Val | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| InhA Ser94Ala | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Moderate-level resistance on gDST | ||||||

| ahpC 48 G > A, KatG Ser315Thr | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| fabG1 15C > Ta, InhA Ile194Thra | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| fabG1 15C > Ta, InhA Ser94Alaa | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| fabG1 15C > T, InhA Ser94Ala | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| fabG1 8 T > Aa, InhA Ile194Thra | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| InhA Ile21Thr, fabG1 15C > Ta | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| InhA Ile21Val, fabG1 15C > Ta | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| InhA Ile21Val, fabG1 8 T > Aa | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| InhA Ser94Ala, fabG1 15C > Ta | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| KatG Ala264Thr | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| KatG Asn138His | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| KatG Asn138Ser | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| KatG Ser315Asn | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| KatG Ser315Thr | 337 | 1 | 0 | 45 | 7 | 284 |

| High-level resistance on gDST | ||||||

| fabG1 15C > Ta, KatG Ser315Glya, InhA Ile194Thra | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| fabG1 15C > T, KatG Ser315Thr | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| katG 2153889_2156147del | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| katG 54_55insAC, fabG1 15C > Ta | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| KatG Met126Ile, InhA Ser94Alaa | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| KatG Ser315Thr, fabG1 15C > Ta | 31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 25 |

| KatG Ser315Thr, InhA Ser94Alaa | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| KatG Ser315Thr, KatG Thr275Ala | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| KatG Trp397Ter | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| KatG Trp90Ter | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| KatG Tyr155Cys, InhA Ile21Val | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 449 | 5 | 17 | 48 | 18 | 361 |

DST, drug susceptibility testing; gDST, genotypic drug susceptibility testing; R, resistant; S, susceptible.

Genomic variants associated with drug resistance having a sequencing depth below the default threshold of 10× but greater than 1×, and with no heteroresistance (i.e. 100% of reads showed that allele).

Statistics

The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used to identify associations between categorical variables. We used Firth multivariable logistic regression models to estimate the correlation between variables of interest showing initial resistance (for ethambutol, fluoroquinolones, isoniazid (pDST alone, genotypic DST (gDST) alone, and a composite variable of both pDST and gDST), kanamycin, ethionamide (results apply to prothionamide as the drug in the shorter treatment regimen), and pyrazinamide) and outcome variables, including “clinically adverse outcome” (failure, relapse, or death), “bacteriologically adverse outcome” (either failure or relapse), and treatment failure only. We adjusted the data for the presence of initial fluoroquinolone resistance, which is known to be the most important predictor of adverse outcome in patients treated with the shorter treatment regimen (Van Deun et al., 2019), and the sampling approach (systematic vs targeted). When DST results were not complete for a variable of interest, we performed a complete case analysis, including only those patients with no missing data for the variables of interest. We used Stata version 14.2 (StataCorp, USA).

Ethics

All patients starting the shorter MDR-TB treatment regimen provided written informed consent. Ethics approval for the present deidentified analysis was provided by the Institute of Tropical Medicine institutional review board.

Results

Patient and bacteriological characteristics

Of 515 patients included in our previous publication (Aung et al., 2014), WGS data were available for 377 patients (73.2%) (Figure 1). We added data from 72 patients with initial resistance to fluoroquinolones and treated with a gatifloxacin-based regimen to obtain an analysis population of 449 patients.

Table 1 summarizes the variables included in the study, stratified by initial fluoroquinolone resistance. Most patients were male (70.4%). Of the 449 patients, 352 (78.4%) initially had fluoroquinolone-susceptible TB, 26 (5.8%) initially had low-level fluoroquinolone-resistant TB, and 71 (15.8%) initially had high-level fluoroquinolone-resistant TB. Of the 449 patients, 344 (76.6%) were cured, 12 (2.7%) completed treatment, 19 (4.2%) were identified as having treatment failure, 8 (1.8%) had relapse, 27 (6.0%) died, and 39 (8.7%) were lost to follow-up.

Frequency of initial resistance

Of the 449 patients, 301 (67.0%) had initial resistance to ethambutol, 147 (32.7%) had initial resistance to pyrazinamide, and 105 (23.4%) had initial resistance to ethionamide (Table 1). Initial kanamycin resistance was found in few patients (n = 6; 1.3%). High-level initial genotypic isoniazid resistance was found in 45 patients (10.0%) and high-level phenotypic resistance to isoniazid was found in 18 of 88 patients (20.5%) with pDST data. Data on the phenotypic level of isoniazid resistance were missing for 361 patients (80.4%). Table 2 shows all variants found in isoniazid-resistance-conferring genes, their classification as susceptible, low-level resistant, moderate-level resistant, and high-level resistant, and their pDST results. No clofazimine resistance was found.

Adverse outcomes

Not considering those lost to follow-up, 13.2% of patients (54/410) had a clinically adverse outcome (treatment failure, relapse, or death) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinically adverse outcome (failure, relapse, or death) by initial resistance to drugs included in the shorter multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment regimen (STR).

| Total | Success |

Failure |

Relapse |

Died |

pc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| 410 | 356 | 86.8 | 19 | 4.6 | 8 | 2.0 | 27 | 6.6 | ||

| FQ | <0.001 | |||||||||

| S | 323 | 302 | 93.5 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 6.2 | |

| R low | 24 | 20 | 83.3 | 2 | 8.3 | 2 | 8.3 | 0 | 0 | |

| R high | 63 | 34 | 54.0 | 16 | 25.4 | 6 | 9.5 | 7 | 11.1 | |

| KAN | 0.001 | |||||||||

| S | 404 | 354 | 87.6 | 16 | 4.0 | 8 | 2.0 | 26 | 6.4 | |

| R | 6 | 2 | 33.3 | 3 | 50.0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 16.7 | |

| INH (gDST) | 0.5 | |||||||||

| S | 20 | 19 | 95.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.0 | |

| R low | 22 | 20 | 90.9 | 2 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| R moderate | 330 | 285 | 86.4 | 13 | 3.9 | 7 | 2.1 | 25 | 7.6 | |

| R high | 38 | 32 | 84.2 | 4 | 10.5 | 1 | 2.6 | 1 | 2.6 | |

| INH (pDST)a | 0.02 | |||||||||

| S | 5 | 5 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| R low | 16 | 15 | 93.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6.3 | |

| R moderate | 42 | 25 | 59.5 | 6 | 14.3 | 6 | 14.3 | 5 | 11.9 | |

| R high | 18 | 9 | 50.0 | 8 | 44.4 | 1 | 5.6 | 0 | 0 | |

| INH (gDST and pDST)a | 0.02 | |||||||||

| S | 4 | 4 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| R low | 16 | 15 | 93.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6.3 | |

| R moderate | 43 | 26 | 60.5 | 6 | 14.0 | 6 | 14.0 | 5 | 11.6 | |

| R high | 18 | 9 | 50.0 | 8 | 44.4 | 1 | 5.6 | 0 | 0 | |

| EMB | 0.2 | |||||||||

| S | 139 | 124 | 89.2 | 3 | 2.2 | 1 | 0.7 | 11 | 7.9 | |

| R | 271 | 232 | 85.6 | 16 | 5.9 | 7 | 2.6 | 16 | 5.9 | |

| PZA | <0.001 | |||||||||

| S | 275 | 250 | 90.9 | 8 | 2.9 | 1 | 0.4 | 16 | 5.8 | |

| R | 135 | 106 | 78.5 | 11 | 8.1 | 7 | 5.2 | 11 | 8.1 | |

| ETH | 0.06 | |||||||||

| S | 316 | 276 | 87.3 | 10 | 3.2 | 7 | 2.2 | 23 | 7.3 | |

| R | 94 | 80 | 85.1 | 9 | 9.6 | 1 | 1.1 | 4 | 4.3 | |

| Sample | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Systematic | 342 | 316 | 92.4 | 3 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.3 | 22 | 6.4 | |

| Targeted | 68 | 40 | 58.8 | 16 | 23.5 | 7 | 10.3 | 5 | 7.4 | |

| WHO STR eligibilityb | 0.003 | |||||||||

| Eligible | 81 | 76 | 93.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6.2 | |

| Resistance to a companion drug | 242 | 226 | 93.4 | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 6.2 | |

| Resistance to FQ (any level) | 19 | 14 | 73.7 | 2 | 10.5 | 1 | 5.3 | 2 | 10.5 | |

EMB, ethambutol; ETH, ethionamide; FQ, fluoroquinolone; gDST, genotypic drug susceptibility testing; high, high, level; INH, isoniazid; KAN, kanamycin; low, low level; moderate, moderate level; pDST, phenotypic drug susceptibility testing; PZA = pyrazinamide; R, resistant S, susceptible.

Data on level of phenotypic isoniazid resistance were missing for 329 patients.

Data from systematic sample only; In this subgroup no patients had tuberculosis initially resistant to second-line injectables; WHO eligible: no resistance to any of the STR components (except isoniazid).

Fisher's exact test.

Among patients with initially fluoroquinolone-susceptible TB, 6.5% (21/323) experienced a clinically adverse outcome, compared with 16.7% (4/24) with low-level resistant TB and 46.0% (29/63) with high-level resistant TB (Table 3). We also found a correlation between clinical outcomes and level of initial resistance to isoniazid on pDST (p = 0.02), and resistance to isoniazid on a combination of pDST and gDST (p = 0.02). As the level of isoniazid resistance increased, the proportion with a successful outcome decreased, with 100%, 93.8%, 59.5%, and 50.0% success on pDST for susceptible, low-level resistant, moderate-level resistant, and high-level resistant TB, respectively. Also pyrazinamide resistance was correlated with clinical outcome (p < 0.001). In the targeted sample, adverse outcomes were more likely (p < 0.001).

High-level fluoroquinolone resistance was associated with a clinically adverse outcome (vs fluoroquinolone-susceptible TB; adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 10.3; 95% confidence interval (CI) 3.1–35.0; p < 0.001) after adjustment for the sampling approach (Table 4). Initial pyrazinamide resistance (aOR 2.0; 95% CI 1.1–3.7; p = 0.04) was associated with a clinically adverse outcome after adjustment for initial fluoroquinolone resistance and the sampling approach. Initial resistance to other companion drugs did not predict clinically adverse outcomes.

Table 4.

Factors associated with having an adverse outcome (clinically or bacteriologically: treatment failure with or without relapse with or without death).

| Success vs FL, RL, or died |

Success vs FL or RL |

Success vs FL |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI | |

| N=410 | N=383 | N=375 | ||||

| Fluoroquinolone resistance | ||||||

| Susceptible | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Low-level resistance | 2.9 | 0.8–10.5 | 34.1*** | 4.3–271.6 | 22.1** | 2.4–207.5 |

| High-level resistance | 10.3*** | 3.1–35.0 | 83.9*** | 10.4–673.9 | 73.0*** | 7.8–679.2 |

| Kanamycin resistance (vs susceptibility) | 2.9 | 0.5–15.5 | 2.7 | 0.5–15.1 | 4.2 | 0.7–25.4 |

| Isoniazid resistance (gDST)a | 1.2 | 0.7–2.2 | 1.3 | 0.6–3.0 | 1.3 | 0.5–3.2 |

| Isoniazid high-level resistance on gDST (vs other) | 0.9 | 0.3–2.6 | 1.4 | 0.4–4.8 | 1.7 | 0.5–6.6 |

| Ethambutol resistance (vs susceptibility) | 1 | 0.5–1.9 | 1.7 | 0.5–5.7 | 1.6 | 0.4–5.9 |

| Pyrazinamide resistance (vs susceptibility) | 2.0* | 1.1–3.8 | 2.6* | 1.01–6.7 | 1.8 | 0.6–5.1 |

| Ethionamide resistance (vs susceptibility) | 1.2 | 0.6–2.4 | 2.2 | 0.8–6.0 | 3.6* | 1.2–11.0 |

| Sampling (targeted vs systematic)b | 1.2 | 0.4–3.9 | 1.7 | 0.4–6.4 | 1.4 | 0.3–6.8 |

| N=81c | N=75c | N=68c | ||||

| Isoniazid resistance (pDST)a | 1.9 | 0.7–5.0 | 2.3 | 0.8–6.5 | 3.6* | 1.01–12.9 |

| Isoniazid high-level resistance on pDST (vs other) | 1.6 | 0.5–4.9 | 2.2 | 0.7–6.8 | 3.8* | 1.03–13.7 |

| Isoniazid resistance (gDST and pDST)a | 1.8 | 0.7–4.8 | 2.3 | 0.8–6.5 | 3.6* | 1.02–12.8 |

| Isoniazid high-level resistance on gDST and pDST (vs other) | 1.6 | 0.5–4.9 | 2.2 | 0.7–6.8 | 3.8* | 1.03–13.7 |

| N=323d | NAe | NAe | ||||

| WHO STR eligibility in patients with FQ-/SLI-susceptible TB | ||||||

| Eligible | 1 | |||||

| Resistance to a companion drug | 1.01 | 0.4–2.8 | ||||

Odds ratios were adjusted for the sampling approach and level of initial resistance to fluoroquinolones.

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; FL, failure; FQ, fluoroquinolone; gDST, genotypic drug susceptibility testing; INH, isoniazid; NA, not applicable; pDST, phenotypic drug susceptibility testing; RL, relapse; SLI, second-line injectable; STR, shorter multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment regimen.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

Odds for every increase between susceptibility, low-level resistance, moderate-level resistance, and high-level resistance.

In addition to the systematic sample, patients with initial FQ resistance were sampled to enrich the cohort.

Missing data: 329 patients for INH pDST and for INH gDST and pDST for success versus FL, RL, or died; 308 patients for INH pDST and for INH gDST and pDST for success versus FL or RL; 307 patients for INH pDST and for INH gDST and pDST for success versus FL.

In patients with FQ-/SLI-susceptible tuberculosis, from systematic sample only; WHO eligible: no resistance to any of the STR components (except isoniazid) (WHO, 2019b).

Regression data not shown: only one patient with treatment failure in 303 patients with initially FQ-susceptible tuberculosis.

Table 4 also shows predictors of bacteriologically adverse outcomes (either failure or relapse), with low-level fluoroquinolone resistance (aOR 34.1; 95% CI 4.3–271.6; p = 0.001), high-level fluoroquinolone resistance (aOR 83.9; 95% CI 10.4–673.9; p < 0.001), and pyrazinamide resistance (aOR 2.6; 95% CI 1.01–6.7; p = 0.048) predicting an adverse outcome.

Predictors of failure included only low-level and high-level fluoroquinolone resistance and ethionamide resistance. For every step increase between susceptibility, low-level resistance, moderate-level resistance, and high-level resistance to isoniazid, the odds of failure increased significantly on either pDST (aOR 3.6; 95% CI 1.01–12.9; p = 0.048) or a combination of pDST and gDST (aOR 3.6; 95% CI 1.02–12.8; p = 0.047). High-level isoniazid resistance (vs any other level) predicted treatment failure on either pDST (aOR 3.8; 95% CI 1.03–13.7; p = 0.04) or a combination of pDST and gDST (aOR 3.8; 95% CI 1.03–13.7; p = 0.04).

Among 342 patients belonging to the systematic sample and treated with the shorter treatment regimen, 81 (23.7%) were eligible on the basis of WHO criteria (only initial resistance to isoniazid is allowed) (WHO, 2019b). Treatment success was 93.3% among 242 patients not eligible because of initial resistance to pyrazinamide, ethionamide, or ethambutol, which is similar to the 93.8% success among 81 patients eligible according to the WHO criteria, and higher than the 73.7% success among 19 patients with initial resistance to fluoroquinolones (Table 3).

In patients with initially fluoroquinolone-susceptible/second-line-injectable-susceptible TB, having initial resistance to pyrazinamide, ethionamide, or ethambutol (and thus not eligible for the shorter treatment regimen according to WHO criteria) (WHO, 2019b) did not predict a clinically adverse outcome (aOR 1.01; 95 %CI 0.4–2.8; p = 1.0; Table 4).

Outcomes in patients with high-level fluoroquinolone resistance

Not considering those who died (n = 7), 34 (60.7%) of 56 patients with high-level fluoroquinolone resistance were cured, while 16 (28.6%) had treatment failure and 6 (10.7%) had relapse (Table 5). Among patients with high-level fluoroquinolone resistance, those with initial resistance to ethionamide were cured less likely than those with TB susceptible to ethionamide (35.7% vs 69.0%; aOR for having a bacteriologically unfavourable outcome: 3.8; 95% CI 1.1–12.9; p = 0.03).

Table 5.

Bacteriologically adverse outcome (either failure or relapse) among patients with high-level fluoroquinolone resistance by initial resistance to drugs included in the shorter treatment regimen.

| Total | Success |

Failure |

Relapse |

pb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| 56 | 34 | 60.7 | 16 | 28.6 | 6 | 10.7 | ||

| KAN | 0.7 | |||||||

| S | 52 | 32 | 61.5 | 14 | 26.9 | 6 | 11.5 | |

| R | 4 | 2 | 50.0 | 2 | 50.0 | 0 | 0 | |

| INH (gDST) | 0.5 | |||||||

| S | 2 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| R low | 3 | 1 | 33.3 | 2 | 66.7 | 0 | 0 | |

| R moderate | 42 | 27 | 64.3 | 10 | 23.8 | 5 | 11.9 | |

| R high | 9 | 4 | 44.4 | 4 | 44.4 | 1 | 11.1 | |

| INH (pDST)a | 0.1 | |||||||

| S | 0 | |||||||

| R low | 1 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| R moderate | 34 | 23 | 67.6 | 6 | 17.6 | 5 | 14.7 | |

| R high | 16 | 7 | 43.8 | 8 | 50.0 | 1 | 6.3 | |

| INH (gDST and pDST)a | 0.1 | |||||||

| S | 0 | |||||||

| R low | 1 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| R moderate | 34 | 23 | 67.6 | 6 | 17.6 | 5 | 14.7 | |

| R high | 16 | 7 | 43.8 | 8 | 50.0 | 1 | 6.3 | |

| EMB | 0.7 | |||||||

| S | 12 | 9 | 75.0 | 2 | 16.7 | 1 | 8.3 | |

| R | 44 | 25 | 56.8 | 14 | 31.8 | 5 | 11.4 | |

| PZA | 0.1 | |||||||

| S | 27 | 20 | 74.1 | 6 | 22.2 | 1 | 3.7 | |

| R | 29 | 14 | 48.3 | 10 | 34.5 | 5 | 17.2 | |

| ETH | 0.03 | |||||||

| S | 42 | 29 | 69.0 | 8 | 19.0 | 5 | 11.9 | |

| R | 14 | 5 | 35.7 | 8 | 57.1 | 1 | 7.1 | |

EMB, ethambutol; ETH, ethionamide; gDST, genotypic drug susceptibility testing high, high level; INH, isoniazid; KAN, kanamycin; low, low level; moderate, moderate level; pDST, phenotypic drug susceptibility testing; PZA, pyrazinamide; R, resistant; S, susceptible.

Data on level of phenotypic isoniazid resistance were missing for five patients.

Fisher's exact test.

In this small subgroup no patient had isoniazid-susceptible TB, and only one patient had low-level isoniazid-resistant TB. High-level isoniazid resistance (vs any other level) on pDST predicted treatment failure (8/15 (53.3%) vs 6/30 (20.0%); aOR 4.3; 95% CI 1.2–15.8; p = 0.03), with the same results for the combination of pDST and gDST.

Discussion

In this study, fluoroquinolone resistance and pyrazinamide resistance were associated with clinically adverse outcome (failure, relapse, or death) and bacteriologically adverse outcome (either failure or relapse) in patients treated with a standardized shorter MDR-TB treatment regimen. Moreover, success was less frequent when the level of isoniazid resistance was higher, and initial resistance to isoniazid was associated with treatment failure. Treatment failure but not relapse was also more likely in patients with initial resistance to ethionamide. In patients with initially fluoroquinolone-/second-line-injectable-susceptible TB, resistance to other drugs in the regimen (ethambutol, ethionamide, or pyrazinamide) was not associated with a clinically adverse outcome.

The association between fluoroquinolone resistance and adverse outcome with the shorter MDR-TB treatment regimen found in this study is in agreement with the findings of previous publications regarding the effectiveness of the regimen (Trébucq et al., 2019, Van Deun et al., 2019), although low-level resistance was not a predictor of failure in a prior analysis of a subset of the present cohort (Rigouts et al., 2016). This supports our understanding of later-generation fluoroquinolones as a core drug of the regimen having both high bactericidal activity and high sterilizing activity (Van Deun et al., 2018). Resistance to fluoroquinolones was not rare (24.4%; 118/483), albeit enriched in our cohort, and the proportion with high-level resistance has increased since the prior analysis. Hence, investments in rapid fluoroquinolone susceptibly testing seem justified. Detection of resistance to fluoroquinolones necessitates replacement by another drug with similar properties, with bedaquiline likely being the best candidate (Van Deun et al., 2018).

Every increase in level (susceptible, low-level resistance, moderate-level resistance, high-level resistance) of phenotypic isoniazid resistance increased the odds of treatment failure, which suggests that high-dose isoniazid continues to contribute to treatment success. These results are in line with findings of other studies (Frieden et al., 1996). A randomized controlled trial that compared high-dose isoniazid (16–18 mg/kg) with normal-dose isoniazid (5 mg/kg) and placebo for the treatment of MDR-TB found that high-dose isoniazid significantly decreased the time to smear conversion (Katiyar et al., 2008). In a study in which MDR-TB patients were treated with a partially standardized regimen, the use of high-dose isoniazid (16–18 mg/kg) was associated with faster culture conversion and higher odds of successful outcome (Walsh et al., 2019). In the latter study, 94% of patients had high-level phenotypic isoniazid resistance, which was defined as resistance at 1.0 mg/L on 7H10 agar medium and corresponds to moderate-level or high-level resistance in our study. A recent study investigating the early bactericidal activity of isoniazid in isoniazid-resistant TB or MDR-TB found that high-dose isoniazid (10–15 mg/kg) is as effective for inhA mutants as normal-dose isoniazid (5 mg/kg) for isoniazid-susceptible TB (Dooley et al., 2020). In contrast, in a study that evaluated the countrywide implementation of the shorter MDR-TB treatment regimen in Niger, no association between the level of resistance to isoniazid and adverse treatment outcome was found (Piubello et al., 2020). This may be explained by the small numbers of patients with failure and relapse in that study, as well as the infrequent occurrence of double mutants of inhA and katG, affecting the power to detect an association.

Among patients with high-level fluoroquinolone resistance, treatment failure was more likely when patients had high-level isoniazid resistance (compared with moderate-level resistance among the vast majority of the remainder). These results suggest that even when high-dose gatifloxacin, a more powerful fluoroquinolone than moxifloxacin is used, high-dose isoniazid is a useful addition in virtually all patients treated with the shorter treatment regimen. Hence, testing for levels of isoniazid resistance (by pDST at a high concentration or by gDST) seems to have value for the constitution of an individualized regimen for fluoroquinolone-resistant MDR-TB.

In contrast to phenotypic resistance, genotypic resistance to isoniazid was not associated with adverse treatment outcome in our study, despite the previously described strong association between drug-resistance-conferring variants and phenotypic resistance levels (Lempens et al., 2018). The very low proportion of patients with isoniazid-susceptible TB may have affected the power to identify an association. Moreover, incomplete genotypic information for isoniazid resistance could have led to small numbers of false negatives. As more information on genotypic resistance patterns emerges through platforms such as ReSeqTB (Starks et al., 2015), we will be able to better explain these inconsistencies.

Bangladeshi people are mostly fast acetylators, which reduces their chance of experiencing adverse effects of isoniazid, in particular with high doses of the drug, compared with slow acetylators (Weber and Hein, 1979, Zaid et al., 2004). Evidence regarding the implementation of the shorter treatment regimen in countries with a larger proportion of slow acetylators shows, however, that adverse events were rare and manageable (Piubello et al., 2020, Trébucq et al., 2019).

We also found a correlation between initial pyrazinamide and ethionamide resistance and adverse treatment outcomes. However, for combination as a single category (any resistance to pyrazinamide, ethionamide, or ethambutol) we did not find a correlation with a clinically or bacteriologically adverse outcome. Treatment success was 93.3% among 242 patients according to WHO criteria not eligible due to resistance to pyrazinamide, ethionamide, or ethambutol, which is very similar to the 93.8% success among 81 eligible patients, and is much higher than the 73.7% success among 19 patients with initial resistance to fluoroquinolones. Hence, the present WHO guidelines (WHO, 2019b), which recommend the shorter treatment regimen not be used in patients with TB resistant to any of the components of the regimen (except isoniazid), may need to be revised, at least for a high-dose gatifloxacin-based regimen. To systematically test for pyrazinamide or ethionamide resistance would result in serious diagnostic delay, as their DST methods are not readily available in most high TB burden countries and for ethionamide DST is not very accurate, and gDST is still problematic, including interpretation of the numerous mutations. Given the high rate of treatment success among those with initial resistance to these drugs, the benefit gained would be questionable. Our findings are supported by other studies evaluating the shorter treatment regimen, some also using the weaker moxifloxacin at the standard dose (Piubello et al., 2020, Trébucq et al., 2019). We were unable to explore the role of second-line injectables, as initial resistance to kanamycin was very rare in this cohort. Moreover, no resistance to clofazimine was found (all isolates had the wild-type Rv0678 gene); hence, the effect of initial resistance to clofazimine could not be assessed.

A targeted sample of patients with fluoroquinolone resistance was included in this study to be able to identify the contribution of companion drugs when fluoroquinolones were no longer driving the regimen’s efficacy. This, however, resulted in higher drug resistance frequencies and worse treatment outcomes than those in the general Damien Foundation Bangladesh MDR-TB/RR—TB population, and may thus limit the generalizability of our findings. Because of the retrospective design of our study, it was not possible to adapt sampling to the research question on the effect of initial resistance on outcome. For example, this led to relatively small groups of patients with low-level or high-level isoniazid resistance compared with moderate-level resistance. However, since we used programme data, our findings represent the reality of the setting. In addition, the Bangladesh dataset has undergone repeated rounds of data verification throughout the years, ensuring a clean and high-quality dataset.

In conclusion, our study confirms that gatifloxacin drives the efficacy of the shorter treatment regimen. Initial resistance to isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethionamide is associated with adverse outcomes; however, the effect on outcomes is not important enough to justify systematic baseline DST, especially when fluoroquinolone susceptibility is preserved. Hence, contrary to current guidelines (WHO, 2019b), exclusions to the regimen may thus be justified only in the case of fluoroquinolone or kanamycin resistance but not other drug resistance.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contribution statement

BdJ, AVD, CM, and LR conceived and designed the study. PL, CM, KA, and MH acquired the data. TD and PL analysed and interpreted the data. PL and TD drafted the article. All authors revised the article critically and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the patients and to the staff of Damien Foundation Bangladesh, and to Damien Foundation Belgium for its financial and logistic support to run the project, including its research activities. We thank Mourad Gumusboga, Elie Nduwamahoro, Cécile Uwizeye, and Sari Cogneau for their dedicated laboratory support, minimum inhibitory concentration determination, and genomic DNA extraction work. We thank Jody Phelan for his support in using TBProfiler. The sequencing work was performed under the direction of David Engelthaler at the Translational Genomics Research Institute through the ReSeqTB sequencing platform led by Marco Schito and supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1115887). BdJ, CM, and LR were supported by the European Research Council (Starting Grant INTERRUPTB 311725).

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.08.042.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Ahmad N., Ahuja Sd, Akkerman Ow, Alffenaar Jc, Anderson Lf, Baghaei P. Treatment correlates of successful outcomes in pulmonary multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;392(10150):821–834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31644-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja Sd, Ashkin D., Avendano M., Banerjee R., Bauer M., Bayona Jn. Multidrug resistant pulmonary tuberculosis treatment regimens and patient outcomes: an individual patient data meta-analysis of 9,153 patients. PLoS Med. 2012;9(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001300. Corrrection PLoS Med 9(9):10.1371/annotation/230240bc-bcf3-46b2-9b21-22e6e584f7333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aung K.J., Van Deun A., Declercq E., Sarker M.R., Das P.K., Hossain M.A. Successful’ 9-month Bangladesh regimen’ for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among over 500 consecutive patients. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(10):1180–1187. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll F., McNerney R., Preston M.D., Guerra-Assunção J.A., Warry A., Hill-Cawthorne G. Rapid determination of anti-tuberculosis drug resistance from whole-genome sequences. Genome Med. 2015;7(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0164-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley K.E., Miyahara S., von Groote-Bidlingmaier F., Sun X., Hafner R., Rosenkranz S.L. Early bactericidal activity of different isoniazid doses for drug resistant TB (INHindsight): a randomized open-label clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(11):1416–1424. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201910-1960OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieden T.R., Sherman L.F., Maw K.L., Fujiwara P.I., Crawford J.T., Nivin B. A multi-institutional outbreak of highly drug-resistant tuberculosis: epidemiology and clinical outcomes. JAMA. 1996;276(15):1229–1235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghodousi A., Tagliani E., Karunaratne E., Niemann S., Perera J., Koser C.U. Isoniazid resistance in mycobacterium tuberculosis is a heterogeneous phenotype composed of overlapping mic distributions with different underlying resistance mechanisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63(7):e00092–19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00092-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katiyar S.K., Bihari S., Prakash S., Mamtani M., Kulkarni H. A randomised controlled trial of high-dose isoniazid adjuvant therapy for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12(2):139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Song L., Breitwieser F.P. Salzberg SL. Centrifuge: rapid and sensitive classification of metagenomic sequences. Genome Res. 2016;26(12):1721–1729. doi: 10.1101/gr.210641.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl T.A., Utpatel C., Schleusener V., De Filippo M.R., Beckert P., Cirillo D.M. MTBseq: a comprehensive pipeline for whole genome sequence analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolates. PeerJ. 2018;6:e5895. doi: 10.7717/peerj.5895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lempens P., Meehan C.J., Vandelannoote K., Fissette K., de Rijk P., Van Deun A. Isoniazid resistance levels of Mycobacterium tuberculosis can largely be predicted by high-confidence resistance-conferring mutations. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):3246. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21378-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan J.E., O’Sullivan D.M., Machado D., Ramos J., Oppong Y.E.A., Campino S. Integrating informatics tools and portable sequencing technology for rapid detection of resistance to anti-tuberculous drugs. Genome Med. 2019;11(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s13073-019-0650-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piubello A., Souleymane M.B., Hassane-Harouna S., Yacouba A., Lempens P., Assao-Neino M.M. Management of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis with shorter treatment regimen in Niger: nationwide programmatic achievements. Respir Med. 2020;161 doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2019.105844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigouts L., Coeck N., Gumusboga M., de Rijk W.B., Aung K.J., Hossain M.A. Specific gyrA gene mutations predict poor treatment outcome in MDR-TB. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(2):314–323. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwœbel V., Trébucq A., Kashongwe Z., Bakayoko A.S., Kuaban C., Noeske J. Outcomes of a nine-month regimen for rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis up to 24 months after treatment completion in nine African countries. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;20 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert M., Catanzaro D., Catanzaro A., Rodwell T.C. Genetic mutations associated with isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starks A.M., Avilés E., Cirillo D.M., Denkinger C.M., Dolinger D.L., Emerson C. Collaborative effort for a centralized worldwide tuberculosis relational sequencing data platform. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(Suppl 3):S141–6. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trébucq A., Decroo T., Van Deun A., Piubello A., Chiang C.Y., Koura K.G. Short-course regimen for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a decade of evidence. J Clin Med. 2019;9(1):55. doi: 10.3390/jcm9010055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trébucq A., Schwoebel V., Kashongwe Z., Bakayoko A., Kuaban C., Noeske J. Treatment outcome with a short multidrug-resistant tuberculosis regimen in nine African countries. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2018;22(1):17–25. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.17.0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Deun A., Decroo T., Kuaban C., Noeske J., Piubello A., Aung K.J.M. Gatifloxacin is superior to levofloxacin and moxifloxacin in shorter treatment regimens for multidrug-resistant TB. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2019;23(9):965–971. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.19.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Deun A., Decroo T., Piubello A., de Jong B.C., Lynen L., Rieder H.L. Principles for constructing a tuberculosis treatment regimen: the role and definition of core and companion drugs. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2018;22(3):239–245. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.17.0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Deun A., Maug A.K., Salim M.A., Das P.K., Sarker M.R., Daru P. Short, highly effective, and inexpensive standardized treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(5):684–692. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0077OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh K.F., Vilbrun S.C., Souroutzidis A., Delva S., Joissaint G., Mathurin L. Improved outcomes with high-dose isoniazid in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment in Haiti. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69(45):717–719. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber W.W., Hein D.W. Clinical pharmacokinetics of isoniazid. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1979;4(6):401–422. doi: 10.2165/00003088-197904060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Companion Handbook to the WHO Guidelines for the Programmatic Management of Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. 2014. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/130918/9789241548809_eng.pdf?sequence=1 Available from: [PubMed]

- WHO Global Tuberculosis Report 2019. 2019. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329368/9789241565714-eng.pdf?ua=1 Available from:

- WHO Rapid Communication: Key Changes to the Treatment of Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. 2019. http://www9.who.int/tb/publications/2019/WHO_RapidCommunicationMDR_TB2019.pdf Available from:

- WHO WHO consolidated guidelines on drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment. 2019. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311389/9789241550529-eng.pdf?ua=1 Available from: [PubMed]

- Zaid R.B., Nargis M., Neelotpol S., Hannan J.M., Islam S., Akhter R. Acetylation phenotype status in a Bangladeshi population and its comparison with that of other Asian population data. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2004;25(6):237–241. doi: 10.1002/bdd.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

WGS reads are available in the European Nucleotide Archive (PRJEB39569). Variables included in the analysis are provided in Supplementary Table 2. Moreover, WGS reads, as well as pDST and clinical data, are included in the ReSeqTB data platform and are accessible on registration at https://platform.reseqtb.org/.

Table 2.

Correlation between genotypic and phenotypic isoniazid (INH) susceptibility testing in 88 patients with data available for both methods.

| Total | Phentotypic DST level of resistance |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | Low | Moderate | High | No data | ||

| Susceptible on gDST | ||||||

| Wild type | 21 | 4 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| ahpC 52C > T | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| ahpC 81C > T | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Low-level resistance on gDST | ||||||

| fabG1 15C > T | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| fabG1 15C > Ta | 13 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| fabG1 17 G > T | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| fabG1 8 T > C | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| InhA Ile194Thra | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| InhA Ile21Val | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| InhA Ser94Ala | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Moderate-level resistance on gDST | ||||||

| ahpC 48 G > A, KatG Ser315Thr | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| fabG1 15C > Ta, InhA Ile194Thra | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| fabG1 15C > Ta, InhA Ser94Alaa | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| fabG1 15C > T, InhA Ser94Ala | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| fabG1 8 T > Aa, InhA Ile194Thra | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| InhA Ile21Thr, fabG1 15C > Ta | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| InhA Ile21Val, fabG1 15C > Ta | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| InhA Ile21Val, fabG1 8 T > Aa | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| InhA Ser94Ala, fabG1 15C > Ta | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| KatG Ala264Thr | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| KatG Asn138His | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| KatG Asn138Ser | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| KatG Ser315Asn | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| KatG Ser315Thr | 337 | 1 | 0 | 45 | 7 | 284 |

| High-level resistance on gDST | ||||||

| fabG1 15C > Ta, KatG Ser315Glya, InhA Ile194Thra | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| fabG1 15C > T, KatG Ser315Thr | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| katG 2153889_2156147del | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| katG 54_55insAC, fabG1 15C > Ta | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| KatG Met126Ile, InhA Ser94Alaa | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| KatG Ser315Thr, fabG1 15C > Ta | 31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 25 |

| KatG Ser315Thr, InhA Ser94Alaa | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| KatG Ser315Thr, KatG Thr275Ala | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| KatG Trp397Ter | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| KatG Trp90Ter | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| KatG Tyr155Cys, InhA Ile21Val | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 449 | 5 | 17 | 48 | 18 | 361 |

DST, drug susceptibility testing; gDST, genotypic drug susceptibility testing; R, resistant; S, susceptible.

Genomic variants associated with drug resistance having a sequencing depth below the default threshold of 10× but greater than 1×, and with no heteroresistance (i.e. 100% of reads showed that allele).