Abstract

This randomized clinical trial investigates whether withholding the standard 48 hours of intravenous empirical antibiotics immediately after birth in preterm infants protects the developing microbiome and improves clinical outcomes.

There is increasing concern regarding antibiotics and the developing infant microbiome. We conducted what is, to our knowledge, the first randomized, double-blinded placebo-controlled trial to test the hypothesis that withholding the standard 48 hours of intravenous empirical antibiotics immediately after birth in preterm infants protects the developing microbiome and improves clinical outcomes.

Methods

Low-risk preterm infants were randomized to receive placebo vs standard dose of ampicillin and gentamicin. Written consent was obtained from the patients’ families per University of Chicago institutional review board protocol. The formal trial protocol can be found in Supplement 1. Clinical characteristics were recorded and assessed using t test for continuous variables and χ2 for categorical variables; a 2-sided P value less than .05 was considered significant. Genomic DNA from fecal samples was subjected to Illumina 16S rRNA sequencing and analyzed per Oliphant et al1; a 2-sided P less than .05 denoted statistical significance.1

Pregnant gnotobiotic germfree mice (E15-17) were gavaged with 0.25-mL placebo (Ab-) vs antibiotic-treated (Ab+) pooled early infant fecal supernatant. Delivered pups acquired the microbiome of interest from the dam. Pup measurements included (1) weight gain and (2) intestinal development by immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence for Lgr5 (stem cell marker), intestinal trefoil factor (TFF3, goblet cell marker), NF-κB (inflammation marker), and ZO-1 (tight junction protein). Behaviors at 12 weeks of age were evaluated by open field and Morris water maze tests.2 The t test was used to detect the difference between the placebo and treatment group. GraphPad Prism 7 was used; 2-sided P value less than .05 was considered significant.

Results

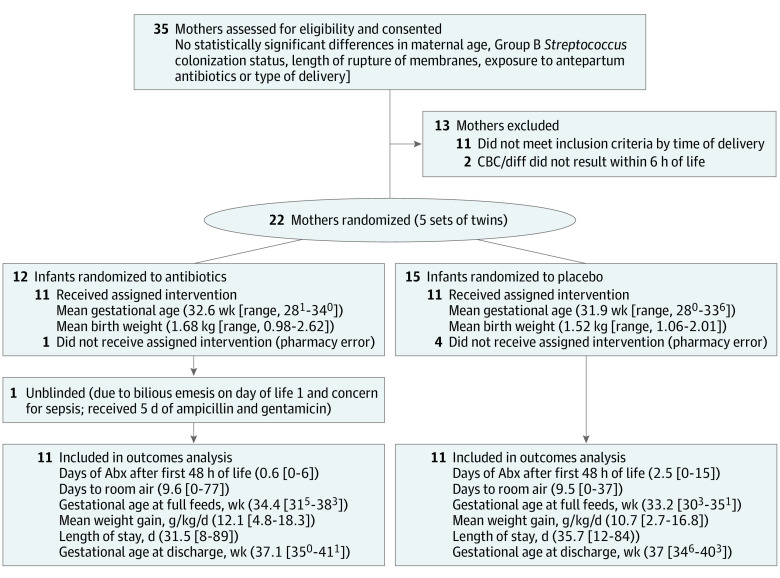

Analysis was based on 22 infants born to 18 mothers randomized to treatment (Ab+; n = 11) vs placebo (Ab-; n = 11). There were no statistically significant differences in maternal or infant characteristics (Figure 1). There were no cases of necrotizing enterocolitis, other preterm infant morbidities, or positive blood cultures. Mean weight gain, time to room air, time to full feeds, length of stay, and discharge gestational age were also the same (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CONSORT Figure.

Figure depicting patient characteristics of the placebo and treatment groups of study. Inclusion criteria for study as per https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02477423 included delivery at 28 weeks' to 34 weeks and 6 days’ gestation without congenital anomalies, rupture of membranes greater than 18 hours, evidence of maternal chorioamnionitis, 5-minute Apgar score less than 5, fraction of inspired oxygen requirement greater than 40%, immature to total neutrophil ratio (I:T) greater than 0.2 on complete blood cell count and differential (CBC/diff) at less than 6 hours of life, seizures or requirement for cardiovascular support in the first 3 hours of life. Sites: the University of Chicago Comer Children’s Hospital, Chicago, Illinois, and Northshore University HealthSystem Evanston Hospital, Evanston, Illinois, from 2015 to 2018. Abx indicates antibiotics.

There were no significant differences in microbiome Shannon diversity (P = .22; R2 = 0.064), species richness (P = .38; R2 = 0.025),k or overall β-diversity (Figure 2A) of fecal samples collected from the first 2 weeks of life between the Ab- and Ab+ groups. Individual taxa were also not significantly different (R2 < 0.10; P ≥ .05) between study groups except that the relative abundance of Actinobacteriota was significantly increased in the Ab+ group (P = .02; R2 = 0.21; Figure 2B). Bifidobacteriaceae family had the largest relative contribution (greater than 70%) to Actinobacteriota abundance.

Figure 2. Effects of Placebo or Antibiotic Treatment on Early Fecal Microbiome Composition and Intestinal Development.

16S rRNA gene sequencing. A, No significant difference in β-diversity at all examined taxonomic levels by permutational multivariate analysis of variance shown in nonmetric multidimensional scaling plot. B, Most phyla (only >1% mean relative abundance presented) were not significantly different between placebo (Ab−) and antibiotic (Ab+), as determined by analysis of variance with patient as a random effect, except Actinobacteriota. C and D, Immunohistochemistry staining of the ileal samples of 2-week-old mice colonized with donor microbiota from Ab− and Ab+ groups (n = 4 to 6 mice). No significant difference in villus length or crypt depth (average of 12 villi or crypts per animal). D, No significant difference in NF-κB activation quantified by percentage of phosphorylated p65 subunit (pp65) positive nuclei/total nuclei. Results are presented as mean (SEM) in C and D. The t test was used to compare between Ab− and Ab+. NMDS indicates nonmetric multidimensional scaling.

aP < .05.

Mouse pups from pregnant dams transfaunated with Ab- vs Ab+ fecal samples had comparable Shannon diversity (mean [SD], 4.47 [1.66] for mice vs 4.48 [5.52] for humans) and overall β-diversity within each group to the human samples and no difference in weight gain, intestinal villus length/crypt depth (Figure 2C), Lgr5-positive cells per crypt, TFF3, ZO-1, phosphorylated NF-κB p65 subunit (pp65) nuclear translocation (Figure 2D), or behaviors (locomotor and anxiety-like behaviors by open field and spatial learning and memory by Morris water maze).

Discussion

Our study failed to demonstrate that withholding 48 hours of standard intravenous antibiotics immediately after birth improved the microbiome or clinical outcomes. Although these findings may challenge beliefs regarding the risks of antibiotics to the developing microbiome, they are consistent with other studies3,4 showing limited effect with a single course of antibiotics and even beneficial effects to early antibiotics for infants born to mothers with possible dysbiosis.3,4 Postmenstrual age is the only significant driver identified so far for development of the preterm infant microbiome, independent of confounders such as delivery mode, breastfeeding, and antibiotics.5 Initial colonization of the preterm infant cannot be assumed to be optimal. Infection may be a specific trigger of preterm birth, and alterations in the maternal microbiome have been associated with preterm delivery.6 Although this study is limited by sample size, initial empirical antibiotic therapy in preterm infants that has a long-standing record as standard of care may not be harmful to the developing microbiome.

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement.

References

- 1.Oliphant K, Cochrane K, Schroeter K, et al. Effects of antibiotic pretreatment of an ulcerative colitis-derived fecal microbial community on the integration of therapeutic bacteria in vitro. mSystems. 2020;5(1):e00404-19. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00404-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu J, Synowiec S, Lu L, et al. Microbiota influence the development of the brain and behaviors in C57BL/6J mice. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0201829. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibson MK, Wang B, Ahmadi S, et al. Developmental dynamics of the preterm infant gut microbiota and antibiotic resistome. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:16024. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ajslev TA, Andersen CS, Gamborg M, Sørensen TI, Jess T. Childhood overweight after establishment of the gut microbiota: the role of delivery mode, pre-pregnancy weight and early administration of antibiotics. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011;35(4):522-529. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.La Rosa PS, Warner BB, Zhou Y, et al. Patterned progression of bacterial populations in the premature infant gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(34):12522-12527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409497111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fettweis JM, Serrano MG, Brooks JP, et al. The vaginal microbiome and preterm birth. Nat Med. 2019;25(6):1012-1021. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0450-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement.