Abstract

Background and aims: Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) FOXD2 adjacent opposite strand RNA 1 (FOXD2-AS1) is aberrantly expressed in various cancers and associated with cancer progression. A comprehensive meta-analysis was performed based on published literature and data in the Gene Expression Omnibus database, and then the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset was used to assess the clinicopathological and prognostic value of FOXD2-AS1 in cancer patients.

Methods: Gene Expression Omnibus databases of microarray data and published articles were used for meta-analysis, and TCGA dataset was also explored using the GEPIA analysis program. Hazard ratios (HRs) and pooled odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to assess the role of FOXD2-AS1 in cancers.

Results: This meta-analysis included 21 studies with 2391 patients and 25 GEO datasets with 3311 patients. The pooled HRs suggested that highly expressed FOXD2-AS1 expression was correlated with poor overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS). Similar results were obtained by analysis of TCGA data for 9502 patients. The pooled results also indicated that FOXD2-AS1 expression was associated with bigger tumor size and advanced TNM stage, but was not related to age, gender, differentiation and lymph node metastasis.

Conclusion: The present study demonstrated that FOXD2-AS1 is closely related to tumor size and TNM stage. Additionally, increased FOXD2-AS1 was a risk factor of OS and DFS in cancer patients, suggesting FOXD2-AS1 may be a potential biomarker in human cancers.

Keywords: FOXD2-AS1, long non-coding RNA, meta-analysis, Neoplasm, prognosis

Introduction

Malignant tumors pose a great threat to human health [1]. Each year, there are approximately 14 million new cases of malignant tumors worldwide and more than 8.2 million deaths [2,3]. The prognosis for cancers is still poor, the difficulties of early cancer diagnosis and the lack of tumor-specific targeted drugs is the main reason [4]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for the identification of tumor-specific diagnostic biomarkers.

Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) was originally discovered during large-scale sequencing of mouse full-length complementary DNA (cDNA) libraries [5], are RNA molecules over 200 nt in length that cannot be translated into proteins [6]. LncRNA was initially considered as noise, but the development of high-throughput sequencing and gene chip technology has revealed that many lncRNAs are abnormally expressed in tumor tissues. These lncRNAs are closely related to tumor resistance, cancer development, invasion and metastasis, suggesting that lncRNAs may be a new class of predictors or therapeutic targets for cancers [7,8]. Some lncRNAs have been identified as prognostic biomarkers for cancer patients, including HOTAIR [9], CRNDE [10], ZEB1-AS1 [11], and PCAT-1 [12].

LncRNA FOXD2 adjacent opposite strand RNA 1 (FOXD2-AS1) is located at chromosome 1p33, and has been linked to deterioration and progression of cancers. FOXD2-AS1 is elevated in several cancers, such as nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NC) [13], hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [14–17], gastric cancer (GC) [18], colorectal cancer (CRC) [19,20], non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [21,22] and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) [22–25], breast cancer [26], glioma [27–30] and so on. The overexpression of FOXD2-AS1 has also been associated with clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of cancers. However, the association between FOXD2-AS1 expression and clinicopathological characteristics in cancers remains controversial, and most studies have been limited by small sample size. Su et al. [31] reported that high FOXD2-AS1 expression was associated with T stage and recurrence, but not with lymph node metastasis and differentiation, and overexpression of FOXD2-AS1 was related to poor overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) in bladder cancer. Xu et al. [18] found that FOXD2-AS1 expression was related to tumor size, TNM stage, and lymphatic metastasis, but not to gender, age and differentiation, and overexpression of FOXD2-AS1 was correlated with a high risk of DFS in GC. Bao et al. [32] found no relationship between FOXD2-AS1 and clinicopathological characteristics, but observed that elevated FOXD2-AS1 expression was associated with a poor OS and DFS in ESCC. Interestingly, Ren et al. [33] reported that FOXD2-AS1 was related to Clark level and distant metastasis, however, FOXD2-AS1 was not related to OS or DFS. To date, there has been a meta-analysis about the FOXD2-AS1, however, the studies included were limited [34], so we performed a comprehensive meta-analysis based on GEO datasets and published articles, and assessed the the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset to analysis the clinicopathological and prognostic value of FOXD2-AS1 in patients in pan-cancers.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and study selection

PubMed, Web of Science, and EMBASE databases were searched for published articles, and FOXD2-AS1 microarray data were extracted from GEO profiles (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geoprofiles/) and GEO datasets (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/). Only GPL570 platform data were used (Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array, HG-U133_Plus_2) to minimize impacts on heterogeneity in later analyses. The databases were searched up to 1 January 2019. The key search words were ‘FOXD2-AS1’ OR ‘Long noncoding RNA FOXD2-AS1’ OR ‘LncRNA FOXD2-AS1’ AND ‘cancers’ or ‘neoplasm’.

We set the inclusion criteria for articles in this meta-analysis as follows: (1) use of qRT-PCR or RNA-seq data to measure the expression of FOXD2-AS1 in tumor tissues; (2) reported association between FOXD2-AS1 expression and clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis; and (3) reported specific hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence interval (CI) or inclusion of sufficient data so that these parameters can be calculated by survival curves.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) conference reports, case reports, reviews, letters, and editorials; (2) studies that only reported the molecular function of FOXD2-AS1; (3) non-human studies in articles; and (4) duplicate articles.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two investigators (Chaojie Liang and Yongping Zhang) performed the search independently and the identified articles were assessed based on the criteria. The extracted data included clinicopathologcial characteristics, OS, and DFS. Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) criteria [35] were used to assess the quality of studies. NOS score ≥ 6 was considered high-quality studies, otherwise, the studies were considered as low-quality.

Public data and tools

A web program named GEPIA was used to analyze the relationship between FOXD2-AS1 and prognosis. In GEPIA, one-way ANOVA was used to analyze the expression of FOXD2-AS1, and the Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test were used to calculate survival analysis, and the cut-off values were analyzed by GEPIA.

Statistical analyses

Statistical data were analyzed by STATA14.2 software. We extracted the HR value with 95% CI from survival curve data by Engauge Digitizer 10.0. Pooled ORs with 95% CIs were calculated for the association of FOXD2-AS1 expression and clinicopathological features. HRs with 95% CIs were calculated to assess the correlation between FOXD2-AS1 expression and prognosis. Heterogeneity was assessed by I2 test and Q test, and the random effect was performed if the I2 > 50%, and when the I2 < 50%, fixed effect was used. We considered the results significant when the pooled OR or HR values with 95% CI did not overlap 1. Sensitivity analysis or subgroup analysis was performed to analyze the presence of heterogeneity and stability of results, and publication bias was assessed by Begg’s funnel.

Results

Study identification and characteristics

The screening process employed is shown in Figure 1. Twenty-one studies [13,14,16–18,20,21,23,29,31,33,36–45] with a total of 2391 patients were selected. The selected studies included four HCC study, two colorectal cancer (CRC) study, one ESCC study, one tongue squamous cell carcinoma study, one GC study, one NC study, one bladder cancer (BC) study, two glioma studies, one NSCLC study, two cutaneous melanoma (CM) study, and two papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) study, one cervical carcinoma (CC) study, one head and neck carcinoma study (HNSC) and one osteosarcoma study (OSC). The studies were selected for inclusion in this meta-analysis based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. These articles were published from 2017 to 2020, the sample size ranged from 50 to 481 patients, and all studies were from China and published in English or Chinese. All studies scored >6 on the NOS, which indicated that all the studies were of high quality. The details of articles are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the meta-analysis.

Table 1. Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Study | Year | Country | Sample size | Tumor type | Cut-off value | Laboratory method | Gender male (Y/N) female (Y/N) | Age old (Y/N) young (Y/N) | Tumor size: big (Y/N) small (Y/N) | Differentiation low (Y/N) high and moderate (Y/N) | Lymph node metastasis yes (Y/N) no (Y/N) | UICC stage I, II (Y/N) III, IV (Y/N) | Survival information | HR | NOS score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen [13] | 2017 | China | 50 | NC | Median | qRT-PCR | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | OS | 2.69 (1.17–5.31) (C) | 6 |

| Bao [23] | 2017 | China | 147 | ESCC | Median | qRT-PCR | 56/60 | 31/35 | 15//10 | 19/13 | 31/35 | 31/35 | OS | 1.94 (1.17–3.06) (R) | 8 |

| 17/14 | 42/39 | 58/64 | 54/61 | 42/29 | 42/39 | DFS | 2.71 (1.53–4.80) (R) | ||||||||

| Rong [21] | 2017 | China | 35 | NSCLC | NA | qRT-PCR | 16/8 | 11/4 | 12/5 | 8/5 | 21/7 | 21/7 | OS | 3.12 (2.29–5.56) (R) | 8 |

| 8/3 | 13/7 | 12/6 | 3/19 | 2/4 | 2/4 | ||||||||||

| Dong [36] | 2018 | China | 124 | Glioma | NA | qRT-PCR | 36/40 | 32/30 | 29/22 | 34/52 | NA | NA | OS | 3.56 (1.48–5.72) (R) | 8 |

| 24/24 | 28/34 | 31/42 | 26/12 | ||||||||||||

| Shen [29] | 2018 | China | 29 | Glioma | Median | qRT-PCR | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | OS | 1.53 (1.02–3.96) (C) | 6 |

| Su [31] | 2018 | China | 84 | BC | Median | qRT-PCR | 34/34 | 20/16 | NA | 6/9 | 14/10 | 14/10 | OS | 2.32 (1.07-5.31) (C) | 7 |

| 8/8 | 22/26 | 36/33 | 28/32 | 28/32 | DFS | 2.12 (1.07–5.31) (C) | |||||||||

| Ren [33] | 2018 | China | 124 | CM | NA | qRT-PCR | 32/34 | 35/32 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 7 |

| 30/28 | 27/30 | ||||||||||||||

| Xu [18] | 2018 | China | 106 | GC | Median | qRT-PCR | 31/35 | 27/30 | 35/20 | 37/38 | 37/36 | 37/36 | DFS | 2.28 (1.30–5.78) (R) | 8 |

| 22/18 | 26/23 | 18/33 | 16/15 | 16/27 | 16/27 | ||||||||||

| Zhang [37] | 2018 | China | 84 | PTC | NA | qRT-PCR | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | OS | 1.65 (1.07–3.96) (C) | 6 |

| Chang [14] | 2018 | China | 360 | HCC | NA | qRT-PCR | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | OS | 1.63 (1.16–2.52) (R) | 8 |

| Zhu [32] | 2018 | China | 481 | CRC | Median | qRT-PCR | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | OS | 1.69 (1.17–2.45) (C) | 6 |

| Chen [39] | 2019 | China | 70 | CM | Median | qRT-PCR | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | OS | 3.332 (1.03–6.09) (R) | 6 |

| Lei [16] | 2019 | China | 88 | HCC | NA | qRT-PCR | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | OS | 1.96 (1.02–3.96) (C) | 6 |

| Li [40] | 2019 | China | 160 | PTC | Median | qRT-PCR | 50/37 | 28/28 | 25/27 | NA | 50/23 | 35/39 | OS | 2.043 (1.579–3.01) (C) | 8 |

| 36/31 | 64/40 | 67/41 | 42/45 | 57/29 | |||||||||||

| Ren [41] | 2019 | China | 35 | OSC | Median | qRT-PCR | 7/8 | NA | 15/7 | NA | NA | 5/9 | OS | 3.06 (1.03–6.98) (C) | 6 |

| 11/9 | 3/10 | 13/8 | |||||||||||||

| Zhang [20] | 2019 | China | 60 | CRC | Median | qRT-PCR | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | OS | 2.245 (1.01–4.32) (C) | 6 |

| Xu [42] | 2019 | China | 105 | HCC | Median | qRT-PCR | 14/15 | 23/21 | 26/14 | 17/19 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 6 |

| 22/21 | 13/15 | 10/22 | 19/17 | ||||||||||||

| Chen [43] | 2019 | China | 85 | HNSC | NA | qRT-PCR | 28/22 | 21/19 | NA | NA | NA | 18/28 | NA | NA | 6 |

| 16/19 | 23/22 | 25/13 | |||||||||||||

| Dou [44] | 2020 | China | 63 | CC | Median | qRT-PCR | NA | 17/19 | 11/13 | 22/17 | 19/9 | NA | OS | 1.73 (1.07–4.52) (C) | 7 |

| 15/12 | 21/18 | 10/14 | 13/22 | ||||||||||||

| Hu [17] | 2020 | China | 60 | HCC | Median | qRT-PCR | 9/8 | 11/9 | 19/9 | 16/5 | NA | 12/26 | NA | NA | 6 |

| 20/23 | 22/18 | 12/20 | 15/24 | 12/10 | |||||||||||

| Zhou | 2020 | China | 41 | TSCC | Median | qRT-PCR | 16/15 | 11/13 | NA | 6/1 | 18/5 | 1/5 | NA | NA | 8 |

| 5/5 | 10/7 | 15/19 | 3/15 | 20/5 |

Abbreviations: C, HR was estimated by curve; N, no; R, HR was reported; Y, yes.

As shown in Tables 2 and 3, 19 GEO databases with 2265 patients were included in this meta-analysis for OS. There were 11 studies from the United States, 14 studies from Western countries, and 6 studies from Asia. Studies of nine different types of tumors were included in the meta-analysis including lung cancer (n=6), colon cancer (n=3), breast cancer (n=3), ovarian cancer (n=2), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL, n=1), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL, n=1), glioblastoma (GBM, n=1), meningioma (n=1), and melanoma (n=1). We also analyzed ten GEO datasets containing records for 1568 patients to calculate DFS. This analysis included three kind of cancers: colon cancer (n=5), breast cancer (n=3), and lung cancer (n=2).

Table 2. OS characteristics of studies based on Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0.

| Type of cancer | GEO number | Year | Country | Number of patients | Outcome measure | Follow-up (month) | Cut-off value | HR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung cancer | GSE3141 | 2005 | U.S.A. | 111 | OS | 87 | Median | 1.426 (0.847–2.402) |

| Colon cancer | GSE17536 | 2009 | U.S.A. | 177 | OS | 142 | Median | 1.043 (0.657–1.647) |

| Colon cancer | GSE17538 | 2009 | U.S.A. | 232 | OS | 142 | Median | 1.326 (0.982–1.992) |

| CLL | GSE22762 | 2011 | Germany | 107 | OS | 72 | Median | 2.121 (0.935–4.816) |

| Lung cancer | GSE30129 | 2011 | France | 293 | OS | 256 | Median | 1.163 (0.876–1.543) |

| Lung cancer | GSE31210 | 2011 | Japan | 226 | OS | 128 | Median | 1.239 (0.738–2.404) |

| Lung cancer | GSE37745 | 2012 | Sweden | 196 | OS | 187 | Median | 0.978 (0.704–1.358) |

| Lung cancer | GSE50081 | 2013 | Canada | 181 | OS | 144 | Median | 1.458 (0.926–2.298) |

| Breast cancer | GSE58812 | 2015 | France | 107 | OS | 169 | Median | 1.491 (0.719–3.09) |

| GBM | GSE7696 | 2008 | Switzerland | 80 | OS | 72 | Median | 1.238 (0.754–2.032) |

| Meningioma | GSE16581 | 2010 | U.S.A. | 67 | OS | 11 | Median | 2.073 (0.659–7.683) |

| Melanoma | GSE19234 | 2009 | U.S.A. | 44 | OS | 186 | Median | 1.574 (0.741–3.865) |

| Ovarian cancer | GSE19829 | 2010 | U.S.A. | 28 | OS | 115 | Median | 1.473 (0.829–4.105) |

| Breast cancer | GSE20711 | 2011 | Canada | 88 | OS | 14 | Median | 1.108 (0.602–2.441) |

| DLBCL | GSE23501 | 2010 | U.S.A. | 69 | OS | 72 | Median | 1.468 (0.792–4.383) |

| Lung cancer | GSE29013 | 2011 | U.S.A. | 55 | OS | 82 | Median | 1.282 (0.8031–3.264) |

| Colon cancer | GSE29623 | 2014 | U.S.A. | 65 | OS | 120 | Median | 1.151 (0.725–2.528) |

| Ovarian cancer | GSE30161 | 2012 | U.S.A. | 58 | OS | 127 | Median | 1.051 (0.643–2.036) |

| Breast cancer | GSE48390 | 2014 | Taiwan | 81 | OS | 69 | Median | 1.234 (0.877–4.035) |

Table 3. DFS characteristics of studies based on Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0.

| Type of cancer | GEO number | Year | Country | Number of patients | Outcome measure | Follow-up (month) | Cut-off value | HR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colon cancer | GSE14333 | 2010 | Australia | 226 | DFS | 142 | Median | 1.432 (0.862–2.998) |

| Colon cancer | GSE17536 | 2009 | U.S.A. | 145 | DFS | 142 | Median | 1.409 (0.791–2.713) |

| Colon cancer | GSE17538 | 2009 | U.S.A. | 200 | DFS | 142 | Median | 1.28 (0.897–2.349) |

| Breast cancer | GSE21653 | 2010 | France | 252 | DFS | 189 | Median | 1.38 (0.884–2.154) |

| Lung cancer | GSE30219 | 2013 | France | 278 | DFS | 256 | Median | 1.528 (1.053–2.215) |

| Colon cancer | GSE38832 | 2014 | U.S.A. | 92 | DFS | 111 | Median | 1.02 (0.273–3.811) |

| Lung cancer | GSE50081 | 2013 | Canada | 177 | DFS | 144 | Median | 1.271 (0.733–2.205) |

| Breast cancer | GSE6532 | 2007 | Canada | 87 | DFS | 202 | Median | 1.948 (0.923–4.111) |

| Colon cancer | GSE29623 | 2014 | U.S.A. | 53 | DFS | 120 | Median | 1.894 (0.513–6.998) |

| Breast cancer | GSE61304 | 2005 | Singapore | 58 | DFS | 85 | Median | 1.335 (0.530–3.364) |

Prognostic value of FOXD2-AS1 for OS

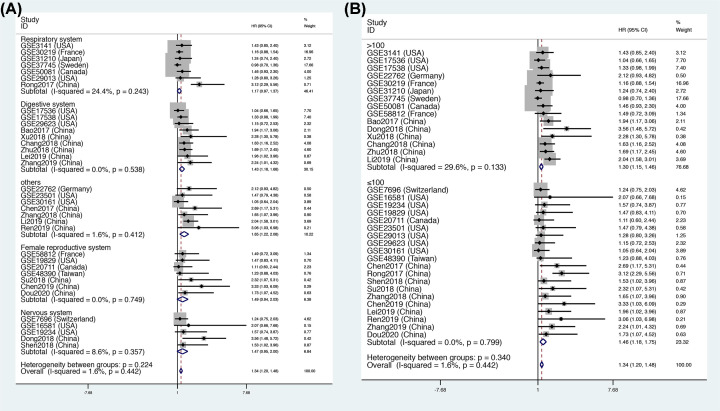

This meta-analysis included data for a total of 4241 patients. The pooled HR indicated that FOXD2-AS1 expression was closely related to a poor OS (HR = 1.34, 95% CI = [1.20, 1.48], P<0.001, Figure 2), and there was no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0). In addition, we performed subgroup analysis according to source, region, tumor type and tumor size, as shown in Table 4. The subgroup analysis for source demonstrated that FOXD2-AS1 expression was correlated with a high risk of OS in the GEO data (OS: HR = 1.17, 95% CI = [1.02, 1.33], P<0.05, Figure 3A) and published articles (OS: HR = 1.95, 95% CI = [1.65, 2.25], P<0.05, Figure 3A). Interestingly, the subgroup analysis for region revealed that the expression of FOXD2-AS1 was associated with poor OS only in Asian subjects (OS: HR = 1.85, 95% CI = [1.58, 2.13], P<0.05, Figure 3B), but not in U.S.A. subjects (OS: HR = 1.22, 95% CI = [0.96, 1.48], P>0.05, Figure 3B) or Western subjects (OS: HR = 1.14, 95% CI = [0.94, 1.34], P>0.05, Figure 3B). The subgroup analysis for tumor type demonstrated that elevated FOXD2-AS1 expression was associated with a poor OS in patients with digestive tumors (OS: HR = 1.43, 95% CI = [1.18, 1.68], P<0.05, Figure 4A) and other tumors (OS: HR = 1.65, 95% CI = [1.22, 2.08], P<0.05, Figure 4A), but not in the respiratory system (OS: HR = 1.17, 95% CI = [0.97, 1.37], P>0.05, Figure 4A), the female reproductive system (OS: HR = 1.47, 95% CI = [0.95, 3.08], P>0.05, Figure 4A), or the nervous system (OS: HR = 1.48, 95% CI = [0.95, 2.00], P>0.05, Figure 4A). When subgroup analysis was conducted according to sample size, the pooled HRs indicated that increased FOXD2-AS1 expression was associated with poor OS in both subgroups (OS: HR = 1.30, 95% CI = [1.14, 1.46], P<0.05, n>100, Figure 4B) (OS: HR = 1.34, 95% CI = [1.20, 1.49], P<0.05, n≤100, Figure 4B).

Figure 2. The relationship between FOXD2-AS1 expression and OS rate.

Table 4. Subgroup analysis of OS by data source, region, tumor type, sample size.

| Subgroups | Number of studies | Number of patients | Pooled HR (95% CI) | PHet | I2(%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data source | ||||||

| Published articles | 16 | 1976 | 1.95 (1.65, 2.25) | 0.889 | 0.0 | <0.05 |

| GEO | 19 | 2265 | 1.17 (1.02, 1.33) | 0.998 | 0.0 | <0.05 |

| Region | ||||||

| U.S.A. | 10 | 906 | 1.22 (0.96–1.48) | 0.994 | 0.0 | >0.05 |

| Western | 7 | 498 | 1.14 (0.94–1.34) | 0.784 | 0.0 | >0.05 |

| Asian | 18 | 2837 | 1.85 (1.58–2.13) | 0.442 | 0.0 | <0.05 |

| Tumor type | ||||||

| Respiratory system | 7 | 1097 | 1.17 (0.97–1.37) | 0.243 | 24.4 | >0.05 |

| Digestive system | 9 | 1716 | 1.43 (1.18–1.68) | 0.538 | 0.0 | <0.05 |

| Others | 7 | 563 | 1.65 (1.22–2.08) | 0.412 | 1.6 | <0.05 |

| Female reproductive system | 7 | 521 | 1.47 (0.95–3.08) | 0.749 | 0.0 | >0.05 |

| Nervous system | 5 | 344 | 1.48 (0.95–2.00) | 0.357 | 8.6 | >0.05 |

| Sample size | ||||||

| >100 | 15 | 3008 | 1.30 (1.14, 1.46) | 0.133 | 29.6 | <0.05 |

| ≤100 | 20 | 1233 | 1.34 (1.20, 1.49) | 0.799 | 0.0 | <0.05 |

Abbreviation: n, number of sample size.

Figure 3. Subgroup analysis of OS.

Subgroup analysis by (A) source and (B) region.

Figure 4. Subgroup analysis of OS.

Subgroup analysis by (A) tumor type and (B) sample size.

Prognostic value of FOXD2-AS1 for DFS

The prognostic value of FOXD2-AS1 for DFS of cancer patients was assayed using data that included 13 studies and 2007 patients; and we found a significant relationship between FOXD2-AS1 and DFS (HR = 1.49, 95% CI = [1.22, 1.76], P<0.05, Figure 5).

Figure 5. Forest plot of DFS.

We performed Begg’s funnel plot analysis to assess potential publication bias. As shown in Figure 6, no significant publication bias was identified for OS (P=0.159, Figure 6A) or DFS (P=0.669, Figure 6C). Sensitivity analysis can assess the stability and reliability of meta-analysis results, and can also assess whether the combined results are affected by a single study by calculating the results when individual studies are omitted and determining if the result is within the CI. Sensitivity analysis was performed and the results are shown in Figure 6B,D, indicating the results were robust and reliable.

Figure 6. Begg’s publication bias plots and sensitivity analysis of studies evaluating the relationship between FOXD2-AS1 expression and survival rate.

(A) Begg’s publication bias of OS. (B) Sensitivity analysis of OS. (C) Begg’s publication bias of DFS. (D) Sensitivity analysis of DFS.

Validation of TCGA dataset results

Next, we explored FOXD2-AS1 expression in all cancer types using data from the TCGA dataset. As shown in Figure 7A, FOXD2-AS1 was overexpressed in cholangiocarcinoma (CHOL), colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), lymphoid neoplasm diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBC), esophageal carcinoma (ESCA), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD), rectum adenocarcinoma (READ), skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM), stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD), and thymoma (THYM), determining using a |log2FC| cutoff > 1 and a q-value < 0.01. A total of 9502 patients with digestive, respiratory, urinary, female reproductive, blood, and urinary systems cancers were included in the analysis. According to FOXD2-AS1 expression, the patients were divided into two groups according to mean expression by GEPIA. The results indicated that FOXD2-AS1 expression was correlated with a high risk of poor OS (Figure 7B) and DFS (Figure 7C). We also explored the prognostic role of FOXD2-AS1 in different tumor types, such as gastrointestinal (GI; Figure 8A,B), hepatobiliary, and pancreatic cancers (Figure 8C,D). As shown in Figure 8, FOXD2-AS1 expression was related to poor OS in hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancer (Figure 8C), urinary cancer (Figure 8G), and head and neck cancers (Figure 8K). However, no significant association was found between FOXD2-AS1 expression and OS in cancers of the respiratory system (Figure 8E). FOXD2-AS1 expression indicated poor DFS in urinary (Figure 8H), respiratory (Figure 8F), and head and neck tumors (Figure 8L), but FOXD2-AS1 expression was not related to DFS in hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancers (Figure 8D). Interestingly, the high expression of FOXD2-AS1 was related to favorable prognosis in GI (Figure 8A,B) and female reproductive cancers (Figure 8I,J).

Figure 7. The expression of FOXD2-AS1 in TCGA dataset.

(A) FOXD2-AS1 expression in CHOL, COAD, DLBC, ESCA, PAAD, READ, SKCM, STAD, and THYM, which was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. ‘*’ means log2FC value > 1 and P-value <0.01. (B) OS rate of FOXD2-AS1 expression in TCGA (n=9502, Log-rank P<0.01). (C) DFS rate of FOXD2-AS1 in TCGA cohort (n=9502, Log-rank P<0.01). Red boxes indicate cancer, and gray boxes indicate normal.

Figure 8. Validation of FOXD2-AS1 expression in TCGA cohort.

(A) OS in GI cancer patients (n=926, Log-rank P=0.013). (B) DFS in GI tumors (n=926, Log-rank P=0.045). (C) OS in hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancer patients (n=578, Log-rank P=0.0014). (D) DFS in hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancer patients (n=578, Log-rank P=0.06). (E) OS in respiratory cancer patients (n=957, Log-rank P=0.23). (F) DFS in respiratory cancer patients (n=957, Log-rank P=0.021). (G) OS in urinary cancer patients (n=1964, Log-rank <0.001). (H) DFS in urinary cancer patients (n=1964, Log-rank =0.001). (I) OS in female reproductive cancer patients (n=1703, Log-rank P=0.0011). (J) DFS in female reproductive cancer patients (n=1703, Log-rank P<0.001). (K) OS in head and neck cancer patients (n=1024, Log-rank P<0.001). (L) DFS in head and neck cancer patients (n=1024, Log-rank P<0.001).

Association between FOXD2-AS1 and clinicopathological characteristics

The pooled ORs with 95% CI were calculated and are shown in Table 5. The pooled results indicated that high FOXD2-AS1 expression was significantly related to larger tumor size (bigger: small: OR = 2.01, 95% CI = [1.56, 2.84], P<0.001, Figure 9C), lymph node metastasis (yes: no, OR = 2.26, 95% CI = [1.22, 4.22], P<0.001, Figure 9E) advanced TNM stage (I+II: III+IV, OR = 0.44, 95% CI = [0.32, 0.60], P=0.012, Figure 9F). However, no significant relationship was identified between FOXD2-AS1 and gender (male: female, OR = 0.88, 95% CI = [0.67, 1.15], P=0992, Figure 9A), age (>60 vs ≤60, OR = 1.19, 95% CI = [0.93, 1.51], P=0.336, Figure 9B) and low differentiation (low: moderate+high, OR = 1.45, 95% CI = [0.73, 2.88], P=0283, Figure 9D). Begg’s funnel plot analysis showed that there was no publication bias for clinicopathological value (gender (P=0.707), age (P=0.452), tumor size (P=0.308), differentiation (P=0.806), or lymph node metastasis (P=0.308), or TNM stage (P=1)).

Table 5. LncRNA FOXD2-AS1 clinicopathological features for cancers.

| Heterogeneity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinicopathological features | Number of studies | Number of patients | Pooled OR (95% CI) | PHet | I2 (%) | P-value | Model used |

| Gender | 12 | 1020 | 0.88 [0.67, 1.15] | 0.992 | 0.0 | 0.992 | Fixed |

| Age | 12 | 1091 | 1.19 [0.93, 1.51] | 0.997 | 0.0 | 0.336 | Fixed |

| Tumor size | 9 | 801 | 2.10 [1.56, 2.84] | 0.172 | 0.0 | <0.001 | Fixed |

| Differentiation | 9 | 812 | 1.45 [0.73, 2.88] | <0.001 | 73.0 | 0.283 | Random |

| Lymph node metastasis | 7 | 629 | 2.26 [1.22, 4.22] | 0.006 | 67.1 | 0.010 | Random |

| TNM stage | 8 | 658 | 0.44 [0.32, 0.60] | 0.614 | 0.0 | <0.001 | Fixed |

Abbreviations: Fixed, fixed-effects model; Random, random-effects model.

Figure 9. Meta-analysis evaluation of the association between FOXD2-AS1 expression and clinicopathological characteristics.

(A) Gender; (B) age; (C) tumor size; (D) differentiation; (E) lymph node metastasis; and (F) TNM stage.

Discussion

Many recent studies have indicated that lncRNA FOXD2-AS1 may play critical roles in the progression and development of cancers. FOXD2-AS1 may be involved in progression of tumors through sponging of tumor-suppressive microRNAs. Zhu et al. [38] proposed that FOXD2-AS1 could competitively sponge miR-185-5p to affect the expression of cell division control protein 42 (CDC42), suggesting that CDC42 is a potential downstream molecule of FOXD2-AS1 in CRC and that the complex axis of FOXD2-AS1/miR-185-5p/CDC42 modulated the proliferation and invasion of CRC. In accordance with this finding, Shen et al. [29] reported that FOXD2-AS1 regulated the malignancy of glioma via the FOXD2-AS1/miR-185-5p/CCND2 axis. Moreover, in glioma, Dong et al. [36] found that FOXD2-AS1 can act as an endogenous sponge of miR-185, which can bind AKT1 to promote cell proliferation and metastasis. In other cancers, FOXD2-AS1 has been suggested to contribute to migration and invasion of tumors by sponging miR-185-5p [15,28–30,36,38,40,46], miR-25-3p [20], miR-98-5p [47], miR-31 [48], miR-7-5p [49], miR-760 [44], miR-195 [24], miR-145-5p [25], miR-363-5p [13,17], miR-143 [50], miR-485-5p [37], and miR-206 [14]. Recent work has shown that lncRNAs influence the occurrence and development of tumors by regulating gene expression at the transcriptional or post-transcriptional level. Su et al. [31] found that FOXD2-AS1 affects hnRNPL regulation of TRIB3 expression by directly binding to the promoter of TRIB3. In addition, FOXD2-AS1 can form a positive feedback loop with AKT and E2F1 to affect the malignant phenotype of bladder cancer. FOXD2-AS1 can also regulate EMT-related proteins by activating signal pathways such as the Notch [19], Wnt/β-catenin [21], Hippo signaling pathway, mTOR, MAP3K1 and PI3K/AKT [31] pathways. And the meta-analysis demonstrated that the expression of FOXD2-AS1 was associated with the tumor size and lymph node metastasis, which may be contributed by which FOXD2-AS1 function as a oncogenic role on the proliferation, migration, invasion in cancers. The mechanisms of action for FOXD2-AS1 as described in published articles are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6. Summary of FOXD2-AS1 with their potential targets, pathways and related microRNAs.

| Cancer type | Expression | Functional role | Related microRNAs | Downstream molecules | Protein binding | Signaling pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal cancer [19,20,38] | up-regulation | Cell proliferation, migration, invasion, EMT | miR-185-5p/miR-25-3P | CDC42/sema4c | / | Notch signaling pathway |

| Bladder cancer [31,50] | up-regulation | Tumor growth, accelerate the gemcitabine-resistance | miR-143 | ABCC3 | / | / |

| NSCLC [21,22] | up-regulation | Cell growth and tumor progression; cisplatin resistance | miR-185-5P | β-catenin/TCF/SIX1 | / | Wnt/β-catenin signaling |

| NC [13] | up-regulation | Cell growth | miR-363-5p | S100A1 | / | / |

| Glioma [27–30,36,46–48] | up-regulation | Cells proliferation, migration, invasion and EMT, and promoted apoptosis; drug resistance | miR-185/miR-185-5 p/miR-98-5p/miR-31 | AKT1/CCND2/p53/ CPEB4/CDK1 | GREB1 | PI3K/AKT |

| Gallbladder cancer [51] | up-regulation | Cell proliferation, migration, and invasion | / | MLH1 | / | / |

| CM [33,52] | up-regulation | Cell proliferation, migration, and invasion | / | / | p-AKT | / |

| GC [18] | up-regulation | Cell growth, cell cycle | / | E2F1/E2F2/CDK4/ EphB3/PCNA | EZH2/LSD1 | / |

| Papillary thyroid cancer [37,40] | up-regulation | cell proliferation, migration and induce cell apoptosis | miR-485-5p/miR-7-5p | KLK7/TERT | / | / |

| HCC [14–17,42] | up-regulation | Cell viability and metastasis;resistance to sorafenib | miR-206/miR-185/miR-150-5p | ANXA2/CDKN1B | EZH2/DKK1 | Wnt/β-catenin signaling MAP3K1/AKT |

| Breast cancer [26,53] | up-regulation | Cell growth, cell cycle | miR-150-5p | PFN2 | S100 | Hippo signaling pathway |

| Cervical cancer [39,44] | up-regulation | Cell proliferation, migration | miR-760 | HDGF | CDX1 | / |

| Esophagus cancer [25] | up-regulation | Cell viability and invasion | miR-145-5p/miR-195 | CDK6 | / | AKT/mTOR |

| Cisplatin resistance | ||||||

| Laryngeal squamous cell [54] | up-regulation | Chemothrapetutic resistance | / | STAT3 | / | / |

In addition to exploring the molecular mechanisms of lncRNA FOXD2-AS1, recent studies have also investigated FOXD2-AS1 as a tumor-specific biomarker. Because most previous studies have been limited by small sample size, we performed a comprehensive meta-analysis and TCGA data review. The results demonstrated that the high expression of FOXD2-AS1 was correlated with advanced clinicopathological features such as tumor size and TNM stage. Moreover, the pooled HRs indicated a significant relationship between FOXD2-AS1 and poor OS, and the subgroup analysis indicated FOXD2-AS1 was related to poor OS for different sources and sample size. However, the expression of FOXD2-AS1 was only correlated with poor OS in digestive tumors, and was not correlated in respiratory, female reproductive and nervous system tumors, suggesting that the mechanism of FOXD2-AS1 may be different in various tumors. When we conducted subgroup analysis based on region, FOXD2-AS1 expression was related to poor OS only in Asian population, but not in American and other Western countries, which suggests that FOXD2-AS1 may be only suitable as a biomarker in the Asian population. We next explored the prognostic value of FOXD2-AS1 in the TCGA dataset, and the results indicated that high expression of FOXD2-AS1 was related to poor OS and DFS in 9502 patients. When we assessed the role of FOXD2-AS1 in different tumor types, FOXD2-AS1 was associated with poor OS in hepatobiliary and pancreatic, urinary, and head and neck cancers, but not in respiratory system tumors. Similarly, FOXD2-AS1 was related to poor DFS in urinary tumors, respiratory tumors, and head and neck tumors. Interestingly, the expression of FOXD2-AS1 was related to favorable prognosis in GI and female reproductive tumors, but more studies are needed to verify the mechanism of FOXD2-AS1 action in various tumors.

Some limitations of the present study should be emphasized. First, all of the included articles are from China, so the conclusions may be only applicable to a Chinese or Asian population. However, we also analyzed data from the GEO database and TCGA dataset. There were some differences in the meta-analysis and analysis of the TCGA dataset. In particular, the meta-analysis reported FOXD2-AS1 was related to poor OS in digestive tumors, however, the TCGA data indicated the opposite result. This may reflect differences in the study populations. Overall, studies should include more patients from different regions. Second, some studies, which have not been published, may influence the publication bias. Third, in some articles, the specific HR value was not provided, and we had to extract the HR value from the K–M curve, a process that may introduce some errors. Fourth, the sample size and tumor types included in this analysis are still limited. Fifth, different cut-off values for up-regulated expression of FOXD2-AS1 were applied in these studies, which may contribute to the data heterogeneity.

Although this article has some limitations, the results are meaningful. The pooled results indicate that the high expression of lncRNA FOXD2-AS1 is associated with larger tumor size and advanced TNM stage. FOXD2-AS1 was also related to a poor OS and DFS in solid tumors, so FOXD2-AS1 may be a potential prognostic biomarker for patients with cancers. However, the role of FOXD2-AS1 may vary in various tumor types, race and regions, so more high-quality datasets and articles with large sample size are needed to verify the role of FOXD2-AS1 in different tumor types and regions.

Abbreviations

- CDC42

cell division control protein 42

- CI

confidence interval

- CLL

chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- DFS

disease-free survival

- ESCC

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- FOXD2-AS1

FOXD2 adjacent opposite strand RNA 1

- GC

gastric cancer

- GI

gastrointestinal

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HR

hazard ratio

- lncRNA

long non-coding RNA

- NC

nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- NOS

Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- OR

odds ratio

- OS

overall survival

- TCGA

the Cancer Genome Atlas

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Project Letter of Academic Leader of the First Hospital of Shanxi Medical University [grant number YD1607]; the Scientific Research Project Plan of Shanxi Provincial Health Planning Commission [grant number 2014029]; the Project Letter of Fostering Team for Precision Medical Key Innovation in the First Hospital of Shanxi Medical University [grant number YT1603]; and the Shanxi International Science and Technology Cooperation Project [grant number 2015081039].

Author Contribution

Chaojie Liang and Jiansheng Guo were responsible for study design. Yongping Zhang and Zhigang Wei were responsible for literature search. Yu Zhang and Zhimin Wang were responsible for data extraction. Chaojie Liang, Zhigang Wei and Ruihuan Li were responsible for data analysis. Jiansheng Guo and Zhigang Wei were responsible for drafting the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D. and Jemal A. (2017) Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J. Clin. 67, 7–30 10.3322/caac.21x387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W., Zheng R., Baade P.D., Zhang S., Zeng H., Bray F. et al. (2016) Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J. Clin. 66, 115–132 10.3322/caac.21338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torre L.A., Sauer A.M., Chen M.S. Jr, Kagawa-Singer M., Jemal A. and Siegel R.L. (2016) Cancer statistics for Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders, 2016: converging incidence in males and females. CA Cancer J. Clin. 66, 182–202 10.3322/caac.21335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Dikshit R., Eser S., Mathers C., Rebelo M. et al. (2015) Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 136, E359–386 10.1002/ijc.29210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okazaki Y., Furuno M., Kasukawa T., Adachi J., Bono H., Kondo S. et al. (2002) Analysis of the mouse transcriptome based on functional annotation of 60,770 full-length cDNAs. Nature 420, 563–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilusz J.E., Sunwoo H. and Spector D.L. (2009) Long noncoding RNAs: functional surprises from the RNA world. Genes Dev. 23, 1494–1504 10.1101/gad.1800909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mercer T.R., Dinger M.E. and Mattick J.S. (2009) Long non-coding RNAs: insights into functions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 155–159 10.1038/nrg2521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angrand P.O., Vennin C., Le Bourhis X. and Adriaenssens E. (2015) The role of long non-coding RNAs in genome formatting and expression. Front. Genet. 6, 165 10.3389/fgene.2015.00165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdeahad H., Avan A., Pashirzad M., Khazaei M., Soleimanpour S., Ferns G.A. et al., 2018The prognostic potential of long noncoding RNA HOTAIR expression in human digestive system carcinomas: a meta-analysis. J. Cell. Physiol. 234, 10926–10933 10.1002/jcp.27918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang C., Zhang B., Ge H., Xu Y., Li G. and Wu J. (2018) Long non-coding RNA CRNDE as a potential prognostic biomarker in solid tumors: a meta-analysis. Clin. Chim. Acta 481, 99–107 10.1016/j.cca.2018.02.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang C., Liu J., Ge H., Xu Y., Li G. and Wu J. (2018) The clinicopathological and prognostic value of long non-coding RNA ZEB1-AS1 in solid tumors: a meta-analysis. Clin. Chim. Acta 484, 91–98 10.1016/j.cca.2018.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang C., Qi Z., Ge H., Liang C., Zhang Y., Wang Z. et al. (2018) Long non-coding RNA PCAT-1 in human cancers: A meta-analysis. Clin. Chim. Acta 480, 47–55 10.1016/j.cca.2018.01.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen G., Sun W., Hua X., Zeng W. and Yang L. (2018) Long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 aggravates nasopharyngeal carcinoma carcinogenesis by modulating miR-363-5p/S100A1 pathway. Gene 645, 76–84 10.1016/j.gene.2017.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang Y., Zhang J., Zhou C., Qiu G., Wang G., Wang S. et al. (2018) Long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 plays an oncogenic role in hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting miR206. Oncol. Rep. 40, 3625–3634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Z., Zhang Z., Zhao D., Feng W., Meng F., Han S. et al. (2019) Long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) FOXD2-AS1 promotes cell proliferation and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating MiR-185/AKT axis. Med. Sci. Monit. 25, 9618–9629 10.12659/MSM.918230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lei T., Zhu X., Zhu K., Jia F. and Li S. (2019) EGR1-induced upregulation of lncRNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma via epigenetically silencing DKK1 and activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Cancer Biol. Ther. 20, 1007–1016 10.1080/15384047.2019.1595276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu W., Feng H., Xu X., Huang X., Huang X., Chen W. et al. (2020) Long noncoding RNA FOXD2-AS1 aggravates hepatocellular carcinoma tumorigenesis by regulating the miR-206/MAP3K1 axis. Cancer Med. 9, 5620–5631 10.1002/cam4.3204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu T.P., Wang W.Y., Ma P., Shuai Y., Zhao K., Wang Y.F. et al. (2018) Upregulation of the long noncoding RNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes carcinogenesis by epigenetically silencing EphB3 through EZH2 and LSD1, and predicts poor prognosis in gastric cancer. Oncogene 37, 5020–5036 10.1038/s41388-018-0308-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang X., Duan B. and Zhou X. (2017) Long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 functions as a tumor promoter in colorectal cancer by regulating EMT and Notch signaling pathway. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 21, 3586–3591 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang M., Jiang X., Jiang S., Guo Z., Zhou Q. and He J. (2019) LncRNA FOXD2-AS1 regulates miR-25-3p/Sema4c axis to promote the invasion and migration of colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Manag. Res. 11, 10633–10639 10.2147/CMAR.S228628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rong L., Zhao R. and Lu J. (2017) Highly expressed long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes non-small cell lung cancer progression via Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 484, 586–591 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.01.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ge P., Cao L., Yao Y.J., Jing R.J., Wang W. and Li H.J. (2019) lncRNA FOXD2-AS1 confers cisplatin resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer via regulation of miR185-5p-SIX1 axis. Onco Targets Ther. 12, 6105–6117 10.2147/OTT.S197454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bao J., Zhou C., Zhang J., Mo J., Ye Q., He J. et al. (2018) Upregulation of the long noncoding RNA FOXD2-AS1 predicts poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Biomarkers 21, 527–533 10.3233/CBM-170260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu H., Zhang J., Luo X., Zeng M., Xu L., Zhang Q. et al. (2020) Overexpression of the long noncoding RNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes cisplatin resistance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma through the miR-195/Akt/mTOR axis. Oncol. Res. 28, 65–73 10.3727/096504019X15656904013079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.Shi W., Gao Z., Song J. and Wang W., Silence of FOXD2-AS1 inhibited the proliferation and invasion of esophagus cells by regulating miR-145-5p/CDK6 axis. Histol. Histopathol. 2020, 18232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang M., Qiu N., Xia H., Liang H., Li H. and Ao X. (2019) Long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1/miR-150-5p/PFN2 axis regulates breast cancer malignancy and tumorigenesis. Int. J. Oncol. 54, 1043–1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao Q.S., Ying J.B., Jing J.J. and Wang S.S. (2020) LncRNA FOXD2-AS1 stimulates glioma progression through inhibiting P53. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 24, 4382–4388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dong H., Cao W. and Xue J. (2019) Long noncoding FOXD2-AS1 is activated by CREB1 and promotes cell proliferation and metastasis in glioma by sponging miR-185 through targeting AKT1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 508, 1074–1081 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.12.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen F., Chang H., Gao G., Zhang B., Li X. and Jin B. (2018) Long noncoding RNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes glioma malignancy and tumorigenesis via targeting miR-185-5p/CCND2 axis. J. Cell. Biochem. 120, 9324–9336 10.1002/jcb.28208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen F., Chang H., Gao G., Zhang B., Li X. and Jin B. (2019) Long noncoding RNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes glioma malignancy and tumorigenesis via targeting miR-185-5p/CCND2 axis. J. Cell. Biochem. 120, 9324–9336 10.1002/jcb.28208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su F., He W., Chen C., Liu M., Liu H., Xue F. et al. (2018) The long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes bladder cancer progression and recurrence through a positive feedback loop with Akt and E2F1. Cell Death Dis. 9, 233 10.1038/s41419-018-0275-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu Y., Li B., Liu Z., Jiang L., Wang G., Lv M. et al. (2017) Up-regulation of lncRNA SNHG1 indicates poor prognosis and promotes cell proliferation and metastasis of colorectal cancer by activation of the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Oncotarget 8, 111715–111727 10.18632/oncotarget.22903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ren W., Zhu Z. and Wu L. (2018) FOXD2-AS1 correlates with the malignant status and regulates cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in cutaneous melanoma. J. Cell. Biochem. 120, 5417–5423 10.1002/jcb.27820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou L., Li Z., Shao X., Yang B., Feng J., Xu L. et al. (2019) Prognostic value of long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 expression in patients with solid tumors. Pathol. Res. Pract. 215, 152449 10.1016/j.prp.2019.152449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stang A. (2010) Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 25, 603–605 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dong H., Cao W. and Xue J. (2018) Long noncoding FOXD2-AS1 is activated by CREB1 and promotes cell proliferation and metastasis in glioma by sponging miR-185 through targeting AKT1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 508, 1074–1081 10.1016/j.bbrc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y., Hu J., Zhou W. and Gao H. (2018) LncRNA FOXD2-AS1 accelerates the papillary thyroid cancer progression through regulating the miR-485-5p/KLK7 axis. J. Cell. Biochem. 10.1002/jcb.28072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu Y., Qiao L., Zhou Y., Ma N., Wang C. and Zhou J. (2018) Long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 contributes to colorectal cancer proliferation through its interaction with microRNA-185-5p. Cancer Sci. 109, 2235–2242 10.1111/cas.13632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen D.Z., Wang T.F., Dai W.C., Xu X. and Chen P.F. (2019) LncRNA FOXD2-AS1 accelerates the progression of cervical cancer via downregulating CDX1. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 23, 10234–10240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li H., Han Q., Chen Y., Chen X., Ma R., Chang Q. et al. (2019) Upregulation of the long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 is correlated with tumor progression and metastasis in papillary thyroid cancer. Am. J. Transl. Res. 11, 5457–5471 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ren Z., Hu Y., Li G., Kang Y., Liu Y. and Zhao H. (2019) HIF-1α induced long noncoding RNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes the osteosarcoma through repressing p21. Biomed. Pharmacother. 117, 109104 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu K., Zhang Z., Qian J., Wang S., Yin S., Xie H. et al. (2019) LncRNA FOXD2-AS1 plays an oncogenic role in hepatocellular carcinoma through epigenetically silencing CDKN1B(p) via EZH2. Exp. Cell Res. 380, 27–204 10.1016/j.yexcr.2019.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen W., Sun S.G., Jiang M.X., Li S.S. and Yuan K. (2019) FOXD2-AS1 is corelated with clinicopathological parameter of laryngeal carcinoma and promote cancer cell proliferation. Lin Chuang er bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi = J. Clin. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 33, 436–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dou X., Zhou Q., Wen M., Xu J., Zhu Y., Zhang S. et al. (2019) Long noncoding RNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes the malignancy of cervical cancer by sponging microRNA-760 and upregulating hepatoma-derived growth factor. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 1700 10.3389/fphar.2019.01700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 45.Zhou G., Huang Z., Meng Y., Jin T., Liang Y. and Zhang B., (2020) Upregulation of long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes progression and predicts poor prognosis in tongue squamous cell carcinoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 10.1111/jop.13074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ni W., Xia Y., Bi Y., Wen F., Hu D. and Luo L. (2019) FoxD2-AS1 promotes glioma progression by regulating miR-185-5P/HMGA2 axis and PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Aging 11, 1427–1439 10.18632/aging.101843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 47.Gu N., Wang X., Di Z., Xiong J., Ma Y., Yan Y. et al. (2019) Silencing lncRNA FOXD2-AS1 inhibits proliferation, migration, invasion and drug resistance of drug-resistant glioma cells and promotes their apoptosis via microRNA-98-5p/CPEB4 axis. Aging 11, 10266–10283 10.18632/aging.102455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang J., Li B., Wang C., Luo Y., Zhao M. and Chen P. (2019) Long noncoding RNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes glioma cell cycle progression and proliferation through the FOXD2-AS1/miR-31/CDK1 pathway. J. Cell. Biochem. 120, 19784–19795 10.1002/jcb.29284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu X., Fu Q., Li S., Liang N., Li F., Li C. et al. (2019) LncRNA FOXD2-AS1 functions as a competing endogenous RNA to regulate TERT expression by sponging miR-7-5p in thyroid cancer. Front. Endocrinol. 10, 207 10.3389/fendo.2019.00207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.An Q., Zhou L. and Xu N. (2018) Long noncoding RNA FOXD2-AS1 accelerates the gemcitabine-resistance of bladder cancer by sponging miR-143. Biomed. Pharmacother. 103, 415–420 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.03.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gao J., Dai C., Yu X., Yin X.B., Liao W.J., Huang Y. et al. (2020) Silencing of long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 inhibits the progression of gallbladder cancer by mediating methylation of MLH1. Gene Ther. 10.1038/s41434-020-00187-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ren W., Zhu Z. and Wu L. (2019) FOXD2-AS1 correlates with the malignant status and regulates cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in cutaneous melanoma. J. Cell. Biochem. 120, 5417–5423 10.1002/jcb.27820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang P. and Xue J. (2020) Long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 regulates the tumorigenesis and progression of breast cancer via the S100 calcium binding protein A1/Hippo signaling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 46, 1477–1489 10.3892/ijmm.2020.4699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li R., Chen S., Zhan J., Li X., Liu W., Sheng X. et al. (2020) Long noncoding RNA FOXD2-AS1 enhances chemotherapeutic resistance of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma via STAT3 activation. Cell Death Dis. 11, 41 10.1038/s41419-020-2232-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]