Summary

Background

Anti-angiogenic therapies such as bevacizumab upregulate hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), a possible mechanism of drug resistance. Camptothecin analogues, including SN-38, have been shown to reduce the expression and transcriptional activity of HIF-1α in preclinical models. We hypothesized that co-administration of pegylated SN-38 (EZN-2208) may offset the induction of HIF-1α following bevacizumab treatment, resulting in synergistic antitumor effects.

Patients and Methods

Patients with refractory solid tumors were enrolled. Objectives were to evaluate the modulation of HIF-1α protein and target genes in tumor biopsies following administration of the combination of EZN-2208 administered weekly×3 (days 1, 8, 15) and bevacizumab administered every 2 weeks, in 28-day cycles, and to establish the safety and tolerability of the combination. Tumor biopsies and dynamic contrast enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) were obtained following bevacizumab alone (before EZN-2208) and after administration of both study drugs.

Results

Twelve patients were enrolled; ten were evaluable for response. Prolonged stable disease was observed in 2 patients, one with HCC (16 cycles) and another with desmoplastic round cell tumor (7 cycles). Reduction in HIF-1α protein levels in tumor biopsies compared to baseline was observed in 5 of 7 patients. Quantitative analysis of DCE-MRI from 2 patients revealed changes in Ktrans and kep. The study closed prematurely as further clinical development of EZN-2208 was suspended by the pharmaceutical sponsor.

Conclusion

Preliminary proof-of-concept for modulation of HIF-1α protein in tumor biopsies following administration of EZN-2208 was observed. Two of 10 patients had prolonged disease stabilization following treatment with the EZN-2208 and bevacizumab combination.

Keywords: Topoisomerase 1 inhibitor, HIF-1α, Irinotecan, Anti-angiogenic therapy, VEGF

Introduction

Hypoxia is a common feature of solid tumors that arises as the tumor mass outgrows its vascular supply, triggering the expression of numerous cell-survival genes mediated by the heterodimeric transcription factor, hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1). HIF-1 facilitates adaptation to oxygen deprivation by upregulating the expression of genes involved in cell survival. While the β subunit of HIF is constitutively expressed, the α subunit is tightly regulated by oxygen levels and undergoes rapid proteasomal degradation in the presence of oxygen [1–4]. Overexpression of HIF-1α has been shown to be associated with poor survival in patients with various cancers [5, 6].

Anti-angiogenic therapies, such as the VEGF inhibitor bevacizumab, can increase intratumoral hypoxia and upregulate HIF-1α, one of the potential mechanisms of resistance to therapy that may contribute tothe relatively low responserates observed with single-agent bevacizumab [7, 8]. EZN-2208 is a water-soluble, polyethylene glycol (PEG)ylated conjugate of SN-38, the active metabolite of the topoisomerase 1 inhibitor, irinotecan [9, 10]. EZN-2208 demonstrated greater efficacy in cell lines and xenograft models compared to irinotecan, along with a longer circulating half-life that produced prolonged drug exposures, supporting a weekly rather than daily infusion schedule [9, 11–14]. In animal models, EZN-2208 has been shown to down-modulate mRNA levels of HIF-1α target genes and to have anti-angiogenic and proapoptotic effects [13].

We conducted a pilot study of weekly EZN-2208 in combination with bevacizumab in patients with refractory solid tumors to determine whether co-administration of EZN-2208 could offset the induction of HIF-1α following bevacizumab administration, and provide clinical benefit. We used a quantitative immunoassay developed and validated by our group to measure levelsofHIF-1α protein in tumor biopsy samples [15]. The objectives of this study were to evaluate the modulation of HIF-1α protein and target genes in tumor biopsies following treatment with the combination of EZN-2208 administered weekly×3 (days 1, 8, 15) and bevacizumab administered every 2 weeks in 28-day cycles; and to establish the safety and tolerability of this drug combination.

Patients and methods

Eligibility criteria

Patients (age ≥18 years) were eligible if they had a pathologically confirmed solid tumor for which standard therapies were no longer effective or for which there was no acceptable standard therapy; had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≤2; and adequate organ and marrow function defined as an absolute neutrophil count ≥1,500/μL, platelets ≥100,000/μL, total bilirubin ≤1.5 X the upper limit of normal (ULN), aspartate aminotransferase and/or alanine aminotransferase <2.5 X ULN, and creatinine <1.5 X ULN. Patients were required to have tumor lesions amenable to biopsy and be willing to undergo paired tumor biopsies.

Patients should have completed prior anticancer therapy at least 4 weeks prior to enrollment and have recovered to eligibility levels from prior treatment-related toxicities. Patients were excluded if they had an uncontrolled intercurrent illness, were pregnant or lactating, or had received treatment for brain metastases within the past 3 months. Prior therapy with irinotecan and/or bevacizumab was allowed. This trial received Institutional Review Board approval; protocol design and conduct followed all applicable regulations, guidances, and local policies (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT01251926).

Trial design

This was an open-label, single arm, pilot trial of EZN-2208 and bevacizumab in patients with advanced, refractory solid tumors. Both study drugs were supplied by the Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, NCI: bevacizumab was obtained under a Collaborative Research and Development Agreement with Genentech; EZN-2208 was obtained under a separate collaborative agreement with Enzon Pharmaceuticals. Bevacizumab (5 mg/kg) was administered intravenously (IV) over 90 min 7 days prior to study day 1 (day −7) and day 15 for cycle 1 only; and on days 1 and 15 for each subsequent cycle, in 28-day cycles; infusion times were reduced to 30–60 min if no adverse reactions occurred. EZN-2208 (9 mg/m2) was administered IV over 60 min on days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28-day cycle. The dose and schedule of bevacizumab at 5 mg/kg every 2 weeks was chosen based on the pivotal colorectal cancer study and FDA labeling [16, 17]. The dose and schedule of EZN-2208 was based on the recommended phase II dose, established from a phase I dose escalation study where dose escalation was stopped at 12 mg/m2 due to dose-limiting toxicity (grade 3 neutropenia) during week 2 that resulted in the inability to deliver the third dose of EZN-2208 during cycle 1. At the 9 mg/m2 cohort, only one patient out of ten had dose-limiting toxicity (febrile neutropenia) during cycle 1, with an overall acceptable safety profile at the recommended phase II dose of 9 mg/m2, days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28-day cycle [18].

Tumor biopsies were obtained on cycle 1 day 1 before EZN-2208 administration (i.e., 7 days after the first dose of bevacizumab) and on cycle 2 day 15 following administration of both study drugs. DCE-MRI was performed at baseline prior to the initial dose of bevacizumab on day −7, on day 1 prior to EZN-2208 administration, and on cycle 2 day 15 following administration of both study drugs.

Adverse events were graded according to NCI Common Toxicity Criteria version 3.0. EZN-2208 doses were reduced to dose level −1 (7 mg/m2) forgrade 3 orgreater toxicities. For bevacizumab-related toxicities, drug was interrupted or discontinued but not reduced; EZN-2208 dosing was continued per schedule. If toxicity required holding bevacizumab administration for more than 4 weeks, bevacizumab was discontinued, with EZN-2208 administration to be continued. For all other grade ≥3 non-hematologic toxicities (except easily correctable electrolyte abnormalities), both agents were held until resolution to grade 1 or baseline. For grade ≥3 hematologic toxicities except lymphopenia and anemia, EZN-2208 was held until resolution to grade ≤2, and then restarted at the next lower dose level, while bevacizumab administration was continued.

All tumor biopsy samples were obtained from metastatic sites by experienced interventional radiologists. During each biopsy procedure, two 18-gauge tumor tissue cores were obtained. One core was processed for HIF-1α protein measurement, and the second was processed for mRNA extraction as described below. Inability to get tissue after a reasonable attempt did not preclude treatment, and the patient remained eligible for therapy and all other translational components including imaging and the clinical endpoints of response and safety. However, the patient was replaced for the purposes of determining the endpoints of HIF-1α protein and target gene modulation. DCE-MRI results were evaluated to assess tumor angiogenesis over two periods: at baseline vs. bevacizumab-treatment only, and vs. combination treatment on treatment cycle 2.

Safety and efficacy evaluations

History, physical examination, and complete blood counts with differential and serum chemistries were performed at baseline and repeated on days 1, 8, and 15, every 28-day cycle for the entire duration of treatment. Radiographic evaluation was performed at baseline and every two cycles to assess tumor response based on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 [19].

HIF-1α immunoassay

Methods for specimen collection to preserve HIF-1α in 18-gauge tumor needle biopsies and an assay to quantitatively measure HIF-1α levels in human tissue biopsy were validated (Supplementary data, online only) [15].

RNA extraction and real-time PCR analysis

Methods are provided in the Supplementary data (online only). Values are expressed as percent change relative to pretreatment samples for each patient.

DCE-MRI

DCE-MRI scans and analysis were performed using standard methods as described in the Supplementary data (online only).

Statistical methods

For purposes of sample size determination, the primary endpoint was the proportion of patients in whom expression of HIF-1α protein in a tumor biopsy decreased by 50 % compared to baseline. The enrollment goal was a total of 15 evaluable patients with paired biopsies and measurable HIF-1α protein levels.

Results

Patient demographics

Twelve patients were enrolled before the study was closed by the pharmaceutical sponsor because further clinical development of EZN-2208 had been temporarily suspended. Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. Ten patients received at least two cycles of therapy, and of these, nine had paired tumor biopsies and were considered evaluable.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | No. of patients |

|---|---|

| Number of patients enrolled/evaluable | 12/9 |

| Male/female | 8/4 |

| Median age, years (range) | 50 (22–76) |

| Median number of prior therapies (range) | 3 (1–6) |

| Patient number/Tumor type: | |

| #1 | Poorly differentiated epidermoid carcinoma of the parotid gland* |

| #2 | Alveolar soft part sarcomaa |

| #3 | Colon adenocarcinomab |

| #4 | Hurthle cell carcinoma of the thyroid* |

| #5 | Colon adenocarcinomaa,* |

| #6 | Hepatocellular carcinomaa, * |

| #7 | Desmoplastic small round cell tumora, * |

| #8 | Mucosal melanoma* |

| #9 | Gastrointestinal stromal tumor* |

| #10 | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma* |

| #11 | Myxoid liposarcomac |

| #12 | Angiosarcoma* |

PD progressive disease, SD stable disease

underwent paired tumor biopsies

stable disease at 8 weeks

only received one dose on C1D1

progressive disease at 6 weeks

Antitumor activity

Four patients had stable disease lasting 2.2, 2.6, 6.8, and 14.6 months, respectively, while at first restaging (8 weeks) seven patients had progressive disease and one was inevaluable (Table 1). Prolonged stable disease was observed in two heavily-pretreated patients. One patient, a 67-year-old man with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), whose disease had progressed following treatment with sorafenib, capecitabine, doxil, and pazopanib, had stable disease lasting 16 cycles. The second patient, a 28-year-old woman with desmoplastic small round cell tumor, whose tumor had progressed following doxorubicin-based multi-agent chemotherapy, pazopanib, irradiation, and a vaccine trial, had stable disease lasting 7 cycles.

Toxicity

There were no unexpected toxicities attributed to the study drug combination; the most common toxicity was neutropenia (Table 2). Five patients had their doses of EZN-2208 reduced because of grade 3/4 neutropenia, and one patient requested a dose reduction for grade 2 fatigue and anemia. All patients developed grade 2 partial thromboplastin time (PTT) prolongation (all patients had normal PTT at baseline) within 1 week of receiving the EZN-2208 infusion. Grade 2 PTT prolongation occurred without associated clinical findings (i.e., no spontaneous or post-biopsy hemorrhage) and was considered probably related to interference in the PTT assay by the pegylation of SN-38 [20]. At the time of PTT prolongation, all patients tested positive for lupus anticoagulant. Nine patients had coagulation factor VIII levels tested that were within normal reference ranges. Five patients were also evaluated for the levels of the coagulation factors IX, XI, and XII—all factor levels were within the normal range other than factor XI, which was 60–66 % in 3 patients, and factor XII, which was 40 % in one patient with HCC and liver cirrhosis (Pt #6). All patients safely underwent tumor biopsies without excessive bleeding.

Table 2.

Adverse events by patient, grade 2 or greater and at least possibly related to the study drug combination (N = 12)

| Adverse events | No. Patients |

|

|---|---|---|

| Grade 2 | Grade 3/4 | |

| Neutropenia | 1 | 6 |

| Lymphopenia | 5 | 2 |

| Leukopenia | 3 | 3 |

| Hypertension | 4 | 2 |

| Anemia | 5 | – |

| PTT prolongation | 10 | – |

| Nausea/vomiting | 4 | – |

| Skin reactions (pruritus, pigmentation, rash) | 4 | – |

| Alopecia | 4 | – |

| Anorexia | 3 | – |

| Dyspepsia/GERD/GI pain | 3 | – |

| Fatigue | 2 | – |

| Oral mucositis | 1 | – |

| Proteinuria | 1 | – |

Two patients withdrew consent: one with alveolar soft part sarcoma (Pt #2) who developed grade 2 anorexia and grade 4 neutropenia; one with colon adenocarcinoma (Pt #3) due to grade 2 fatigue and grade 1 weight loss. One patient with colon adenocarcinoma (Pt #5) had stable disease but came off study due to grade 3 neutropenia despite dose reduction to 7 mg/m2 of EZN-2208; no further dose reduction was allowed per protocol for this patient.

HIF-1α protein levels

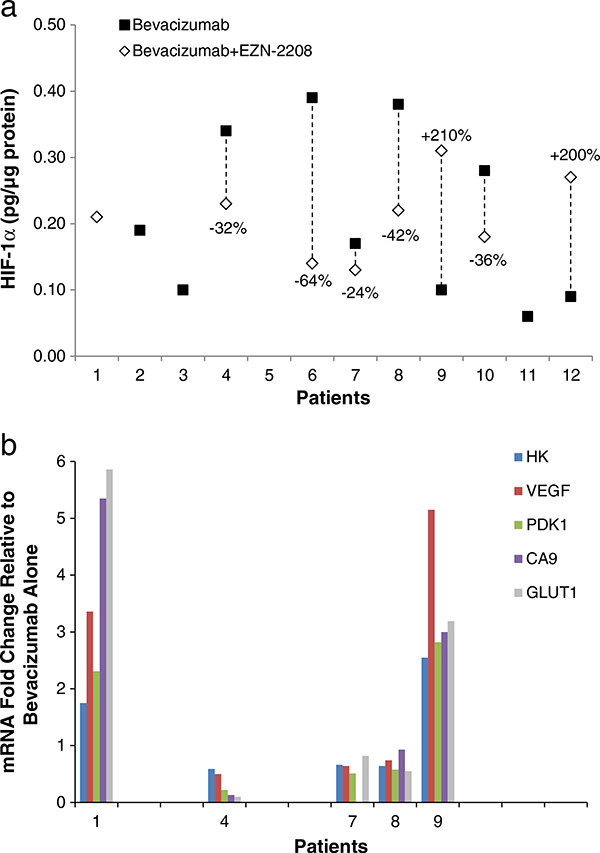

Twelve patients agreed to undergo tumor biopsies; paired biopsies were collected from nine patients (Table 1). There was insufficient protein content to perform the HIF-1α immunoassay on paired samples from two patients (Pts #1, 5). Two patients had HIF-1α levels below the lower limit of quantification (LLQ) of the assay in either the baseline (Pt #12) or the post-treatment sample (Pt #10); therefore, actual assay LLQ values were graphed. Of the seven patients with sufficient protein content, one (Pt #6) had a greater than 50 % decrease in protein level (0.39 pg/μg baseline to 0.14 pg/μg post-dose) and four other patients had greater than 20 % decreases in protein levels. Two patients (Pts #9 and 12) had an increase in HIF-1α protein levels (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

a HIF-1α protein levels in paired tumor biopsies collected from seven patients following administration of bevacizumab only (black square) and combination bevacizumab and EZN-2208 (white diamond). HIF-1α levels for Patients 10 (post combination dose) and 12 (bevacizumab only) were below the assay lower limit of quantitation, which is the value reported. Where no vertical line is drawn (Patients 1, 2, 3, and 11) only one biopsy sample was collected or one sample either contained insufficient protein content to perform the HIF-1α immunoassay or failed assay quality control criteria. Both samples from Patient 5 contained insufficient protein. b. mRNA levels of five selected HIF-1α target genes in five evaluable paired tumor biopsies collected following administration of bevacizumab only and combination bevacizumab and EZN-2208. Expression of HK2, VEGF, PDK1, CA9, and GLUT1 are expressed as fold-change mRNA expression relative to levels observed after bevacizumab alone for each patient

Expression of HIF-1α target genes

Assessment of changes in the expression of select HIF-1α target genes (Table 3) was performed in five patients from whom sufficient RNA was a vailable from paired tumor biopsies (Fig. 1b). Gene expression was measured relative to levels observed after administration of single-agent bevacizumab. Three of these patients had consistent decreases in all five target genes (Pts #4, 7, 8) following the study drug combination; these three patients also had a greater than 20 % decrease in HIF-1α protein levels. The remaining two patients (Pts #1, 9) had consistent increases in all of the HIF-1α target genes measured; insufficient protein was available in the baseline sample for Pt #1 to allow paired sample comparison and Pt #9 had a 210 % increase in HIF-1α protein post-baseline.

Table 3.

Selected HIF-1α target genes measured in the study

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Function |

|---|---|---|

| HK2 | Hexokinase 2 | Hexokinases phosphorylate glucose to produce glucose-6-phosphate |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor A | Growth factor active in angiogenesis, vasculogenesis and endothelial cell growth |

| PDK1 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, isozyme 1 | Inhibits the mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, thus contributing to the regulation of glucose metabolism |

| CA9 | Carbonic anhydrase 9 | Reversible hydration of carbon dioxide. Participates in pH regulation |

| GLUT1 | Solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transport), member 1 | Facilitative glucose transport. |

DCE-MRI

Evaluable data from all three DCE-MRIs were available for only two patients. The first, a patient with HCC (Pt #6), had a 21 % decrease in Ktrans value and a 33 % decrease in kep value between the initial dose of bevacizumab (day −7) and the second DCE-MRI on cycle 1 day 1. After EZN-2208 was added, there was 1 % increase in Ktrans value and a 14 % further decrease in kep value by the third DCE-MRI on cycle 2 day 15. The second, a patient with gastrointestinal stromal tumor (Pt #9), had a 45 % decrease in Ktrans value and a 51 % decrease in kep value between the initial dose of bevacizumab and cycle 1 day 1, and there were further decreases of 27 % and 14 % in Ktrans and kep values, respectively, by cycle 2 day 15. Pt #6 had stable disease for 16 cycles, but Pt #9 had progressive disease within 2 cycles despite the decreased DCE-MRI vascularity index. Two additional patients had two DCE-MRI scans before the initial dose of bevacizumab and on cycle 1 day 1 only: Pt #5 had a 2 % decrease in Ktrans value and a 42 % increase in kep value, and Pt #12 had 93 % and 88 % increases in Ktrans and kep values, respectively.

Discussion

We conducted a pilot study of EZN-2208 in combination with bevacizumab in patients with refractory solid tumors to determine whether co-administration of EZN-2208 could offset the induction of HIF-1α following bevacizumab administration. The combination of EZN-2208 and bevacizumab was safe with acceptable toxicity. Four patients (33 %) had grade 1 diarrhea, which was less than expected since treatment with irinotecan has been reported to cause life-threatening diarrhea in up to 25 % of patients [21, 22]. The prolonged PTT reported in all study patients has been reported in other studies of EZN-2208, and is most likely an effect of the pegylation of SN-38 based on studies evaluating the use of PEG as a platelet cryoprotectant [18, 20].

Conclusive demonstration of the effects of EZN-2208 treatment on levels of HIF-1α in tumor tissue could not be obtained because the study was closed prematurely. Only one patient met the study objective of a greater than 50 % decrease in HIF-1α protein levels. While four patients had a greater than 20 % decrease in HIF-1α protein levels, this is within the expected baseline heterogeneity in human samples and should not be considered a true decrease in HIF-1α protein. Historically, levels of HIF-1α protein have been difficult to measure in human tumor biopsies due to limited sample material, heterogeneity of HIF-1α expression, and the inherent instability of HIF-1α in the presence of oxygen [4]. In addition, HIF-1α measurements by immunohistochemistry or Western blot analyses are semi-quantitative, prone to sampling error, and require relatively large amounts of protein, limiting their usefulness in human needle biopsy specimens. Therefore, a validated ELISA for quantitation of HIF-1α protein levels was developed within our group, along with standard operating procedures (SOPs) using degassed buffers, to minimize exposure to oxygen. This immunoassay allowed reliable and reproducible quantification of HIF-1α protein from human biopsy samples [15].

Due to the limited number of patient samples analyzed, no correlation between HIF-1α protein levels and mRNA response or tumor blood flow could be determined. The only patient with a >50 % decrease in HIF-1α protein levels, Pt #6, did not have mRNA analysis performed. Patient #9 had a 210 % increase in HIF-1α protein levels and also had a greater than 2-fold increase in target gene expression and a 5-fold increase in VEGF expression, but DCE-MRI analysis showed inconsistent modulation of tumor blood flow and permeability. Establishing whether there is any correlation between changes in HIF-1α protein or mRNA level and modulation of blood flow in tumor tissue will require a larger data set. This study highlights the difficulties in demonstrating statistically significant modulation of targets in tumor tissues obtained from patients due to the biologic complexity as well as logistical challenges.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Yvonne A. Evrard and Yiping Zhang for assistance with pharmacodynamic analysis in the preparation of this manuscript. This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest None declared.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10637-013-0048-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Woondong Jeong, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Sook Ryun Park, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Annamaria Rapisarda, Leidos Biomedical Research, Inc., Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Frederick, MD 21702, USA.

Nicole Fer, Leidos Biomedical Research, Inc., Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Frederick, MD 21702, USA.

Robert J. Kinders, Leidos Biomedical Research, Inc., Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Frederick, MD 21702, USA

Alice Chen, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Giovanni Melillo, Leidos Biomedical Research, Inc., Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Frederick, MD 21702, USA.

Baris Turkbey, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Seth M. Steinberg, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA

Peter Choyke, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

James H. Doroshow, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Shivaani Kummar, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA; Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

References

- 1.Semenza G (2007) Hypoxia and cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev 26(2):223–224. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9058-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhong H, De Marzo AM, Laughner E, Lim M, Hilton DA, Zagzag D, Buechler P, Isaacs WB, Semenza GL, Simons JW (1999) Overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α in common human cancers and their metastases. Cancer Res 59(22):5830–5835 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bos R, Zhong H, Hanrahan CF, Mommers ECM, Semenza GL, Pinedo HM, Abeloff MD, Simons JW, van Diest PJ, van der Wall E (2001) Levels of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α during breast carcinogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst 93(4):309–314. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.4.309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang LE, Gu J, Schau M, Bunn HF (1998) Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α is mediated by an O2-dependent degradation domain via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95(14):7987–7992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birner P, Schindl M, Obermair A, Breitenecker G, Oberhuber G (2001) Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha in epithelial ovarian tumors: its impact on prognosis and on response to chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 7(6):1661–1668 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aebersold DM, Burri P, Beer KT, Laissue J, Djonov V, Greiner RH, Semenza GL (2001) Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha: a novel predictive and prognostic parameter in the radiotherapy of oropharyngeal cancer. Cancer Res 61(7):2911–2916 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis LM, Hicklin DJ (2008) VEGF-targeted therapy: mechanisms of anti-tumour activity. Nat Rev Cancer 8(8):579–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rapisarda A, Shoemaker RH, Melillo G (2009) Antiangiogenic agents and HIF-1 inhibitors meet at the crossroads. Cell Cycle 8(24):4040–4043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sapra P, Zhao H, Mehlig M, Malaby J, Kraft P, Longley C, Greenberger LM, Horak ID (2008) Novel delivery of SN38 markedly inhibits tumor growth in xenografts, including a camptothecin-11-refractory model. Clin Cancer Res 14(6):1888–1896. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-07-4456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurzrock R, Goel S, Wheler J, Hong D, Fu S, Rezai K, Morgan-Linnell SK, Urien S, Mani S, Chaudhary I, Ghalib MH, Buchbinder A, Lokiec F, Mulcahy M (2012) Safety, pharmacokinetics, and activity of EZN-2208, a novel conjugate of polyethylene glycol and SN38, in patients with advanced malignancies. Cancer 118(24): 6144–6151. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sapra P, Kraft P, Mehlig M, Malaby J, Zhao H, Greenberger LM, Horak ID (2009) Marked therapeutic efficacy of a novel polyethylene glycol-SN38 conjugate, EZN-2208, in xenograft models of B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Haematologica 94(10):1456–1459. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.008276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao H, Rubio B, Sapra P, Wu D, Reddy P, Sai P, Martinez A, Gao Y, Lozanguiez Y, Longley C, Greenberger LM, Horak ID (2008) Novel prodrugs of SN38 using multiarm poly(ethylene glycol) linkers. Bioconjug Chem 19(4):849–859. doi: 10.1021/bc700333s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sapra P, Kraft P, Pastorino F, Ribatti D, Dumble M, Mehlig M, Wang M, Ponzoni M, Greenberger L, Horak I (2011) Potent and sustained inhibition of HIF-1alpha and downstream genes by a polyethyleneglycol-SN38 conjugate, EZN-2208, results in anti-angiogenic effects. Angiogenesis 14(3):245–253. doi: 10.1007/s10456-011-9209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zander SAL, Sol W, Greenberger L, Zhang Y, van Tellingen O, Jonkers J, Borst P, Rottenberg S (2012) EZN-2208 (PEG-SN38) overcomes ABCG2-mediated topotecan resistance in BRCA1-deficient mouse mammary tumors. PLoS One 7(9):e45248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park SR, Kinders RJ, Khin S, Hollingshead M, Parchment RE, Tomaszewski JE, Doroshow JH (2012) Validation and fitness testing of a quantitative immunoassay for HIF-1 alpha in biopsy specimens [abstract]. Cancer Res 72 (8):3616 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, Berlin J, Baron A, Griffing S, Holmgren E, Ferrara N, Fyfe G, Rogers B, Ross R, Kabbinavar F (2004) Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 350(23):2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Label information for Avastin (bevacizumab) [homepage on the Internet] (2004) United States Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation Research; http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/125085s225lbl.pdf. Accessed October 29 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patnaik A, Papadopoulos K, Tolcher A, Beeram M, Urien S, Schaaf L, Tahiri S, Bekaii-Saab T, Lokiec F, Rezai K, Buchbinder A (2013) Phase I dose-escalation study of EZN-2208 (PEG-SN38), a novel conjugate of poly(ethylene) glycol and SN38, administered weekly in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 71(6): 1499–1506. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2149-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L, Shankar L, Dodd L, Kaplan R, Lacombe D, Verweij J (2009) New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 45(2):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakaltcheva I, Ganong JP, Holtz BL, Peat RA, Reid T (2000) Effects of high-molecular-weight cryoprotectants on platelets and the coagulation system. Cryobiology 40(4):283–293. doi: 10.1006/cryo.2000.2247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iyer L, King CD, Whitington PF, Green MD, Roy SK, Tephly TR, Coffman BL, Ratain MJ (1998) Genetic predisposition to the metabolism of irinotecan (CPT-11). Role of uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase isoform 1A1 in the glucuronidation of its active metabolite (SN-38) in human liver microsomes. J Clin Invest 101(4):847–854. doi: 10.1172/jci915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu Z-Y, Yu Q, Zhao Y-S (2010) Dose-dependent association between UGT1A1*28 polymorphism and irinotecan-induced diarrhoea: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 46(10):1856–1865. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.