Abstract

Background

Free-text descriptions in electronic health records (EHRs) can be of interest for clinical research and care optimization. However, free text cannot be readily interpreted by a computer and, therefore, has limited value. Natural Language Processing (NLP) algorithms can make free text machine-interpretable by attaching ontology concepts to it. However, implementations of NLP algorithms are not evaluated consistently. Therefore, the objective of this study was to review the current methods used for developing and evaluating NLP algorithms that map clinical text fragments onto ontology concepts. To standardize the evaluation of algorithms and reduce heterogeneity between studies, we propose a list of recommendations.

Methods

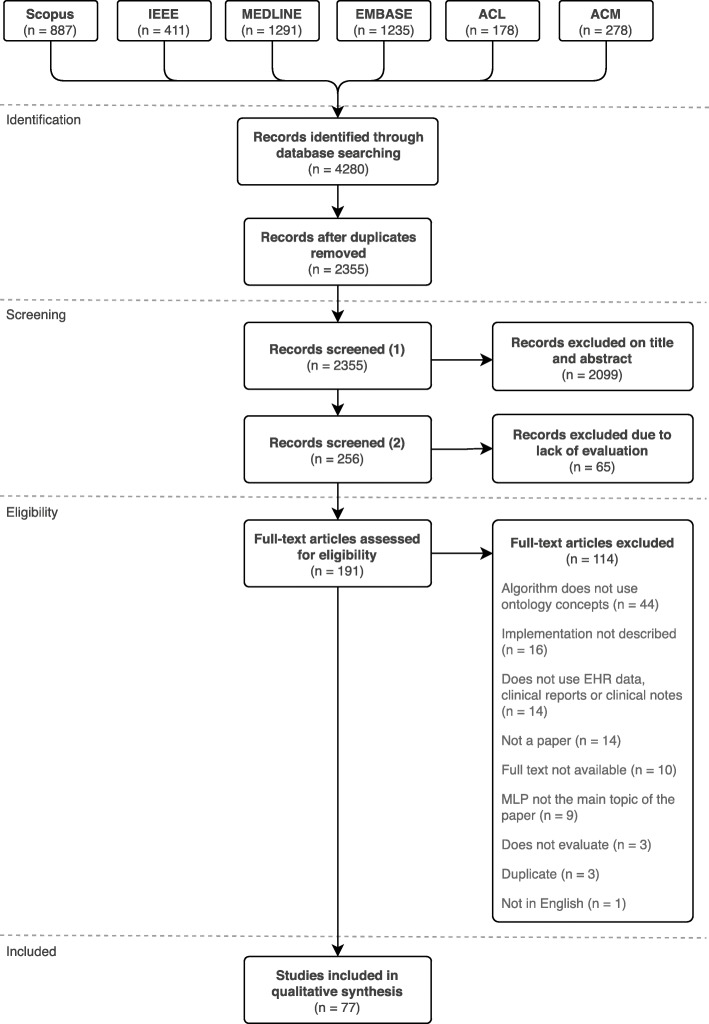

Two reviewers examined publications indexed by Scopus, IEEE, MEDLINE, EMBASE, the ACM Digital Library, and the ACL Anthology. Publications reporting on NLP for mapping clinical text from EHRs to ontology concepts were included. Year, country, setting, objective, evaluation and validation methods, NLP algorithms, terminology systems, dataset size and language, performance measures, reference standard, generalizability, operational use, and source code availability were extracted. The studies’ objectives were categorized by way of induction. These results were used to define recommendations.

Results

Two thousand three hundred fifty five unique studies were identified. Two hundred fifty six studies reported on the development of NLP algorithms for mapping free text to ontology concepts. Seventy-seven described development and evaluation. Twenty-two studies did not perform a validation on unseen data and 68 studies did not perform external validation. Of 23 studies that claimed that their algorithm was generalizable, 5 tested this by external validation. A list of sixteen recommendations regarding the usage of NLP systems and algorithms, usage of data, evaluation and validation, presentation of results, and generalizability of results was developed.

Conclusion

We found many heterogeneous approaches to the reporting on the development and evaluation of NLP algorithms that map clinical text to ontology concepts. Over one-fourth of the identified publications did not perform an evaluation. In addition, over one-fourth of the included studies did not perform a validation, and 88% did not perform external validation. We believe that our recommendations, alongside an existing reporting standard, will increase the reproducibility and reusability of future studies and NLP algorithms in medicine.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13326-020-00231-z.

Keywords: Ontologies, Entity linking, Annotation, Concept mapping, Named-entity recognition, Natural language processing, Evaluation studies, Recommendations for future studies

Background

One of the main activities of clinicians, besides providing direct patient care, is documenting care in the electronic health record (EHR). Currently, clinicians document clinical findings and symptoms primarily as free-text descriptions within clinical notes in the EHR since they are not able to fully express complex clinical findings and nuances of every patient in a structured format [1, 2]. These free-text descriptions are, amongst other purposes, of interest for clinical research [3, 4], as they cover more information about patients than structured EHR data [5]. However, free-text descriptions cannot be readily processed by a computer and, therefore, have limited value in research and care optimization.

One method to make free text machine-processable is entity linking, also known as annotation, i.e., mapping free-text phrases to ontology concepts that express the phrases’ meaning. Ontologies are explicit formal specifications of the concepts in a domain and relations among them [6]. In the medical domain, SNOMED CT [7] and the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) [8] are examples of widely used ontologies to annotate clinical data. After the data has been annotated, it can be reused by clinicians to query EHRs [9, 10], to classify patients into different risk groups [11, 12], to detect a patient’s eligibility for clinical trials [13], and for clinical research [14].

Natural Language Processing (NLP) can be used to (semi-)automatically process free text. The literature indicates that NLP algorithms have been broadly adopted and implemented in the field of medicine [15, 16], including algorithms that map clinical text to ontology concepts [17]. Unfortunately, implementations of these algorithms are not being evaluated consistently or according to a predefined framework and limited availability of data sets and tools hampers external validation [18].

To improve and standardize the development and evaluation of NLP algorithms, a good practice guideline for evaluating NLP implementations is desirable [19, 20]. Such a guideline would enable researchers to reduce the heterogeneity between the evaluation methodology and reporting of their studies. Generic reporting guidelines such as TRIPOD [21] for prediction models, STROBE [22] for observational studies, RECORD [23] for studies conducted using routinely-collected health data, and STARD [24] for diagnostic accuracy studies, are available, but are often not used in NLP research. This is presumably because some guideline elements do not apply to NLP and some NLP-related elements are missing or unclear. We, therefore, believe that a list of recommendations for the evaluation methods of and reporting on NLP studies, complementary to the generic reporting guidelines, will help to improve the quality of future studies.

In this study, we will systematically review the current state of the development and evaluation of NLP algorithms that map clinical text onto ontology concepts, in order to quantify the heterogeneity of methodologies used. We will propose a structured list of recommendations, which is harmonized from existing standards and based on the outcomes of the review, to support the systematic evaluation of the algorithms in future studies.

Methods

This study consists of two phases: a systematic review of the literature and the formation of recommendations based on the findings of the review.

Literature review

A systematic review of the literature was performed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [25].

Search strategy and study selection

We searched Scopus, IEEE, MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) Digital Library, and the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL) Anthology for the following keywords: Natural Language Processing, Medical Language Processing, Electronic Health Record, reports, charts, clinical notes, clinical text, medical notes, ontolog*, concept*, encod*, annotat*, code, and coding. We excluded the words ‘reports’ and ‘charts’ in the ACL and ACM databases since these databases also contain publications on non-medical subjects. The detailed search strategies for each database can be found in Additional file 2. We searched until December 19, 2019 and applied the filters “English” and “has abstract” for all databases. Moreover, we applied the filters “Medicine, Health Professions, and Nursing” for Scopus, the filters “Conferences”, “Journals”, and “Early Access Articles” for IEEE, and the filter “Article” for Scopus and EMBASE. EndNote X9 [26] and Rayyan [27] were used to review and delete duplicates.

The selection process consisted of three phases. In the first phase, two independent reviewers with a Medical Informatics background (MK, FP) individually assessed the resulting titles and abstracts and selected publications that fitted the criteria described below.

Inclusion criteria were:

Medical language processing as the main topic of the publication

Use of EHR data, clinical reports, or clinical notes

Algorithm performs annotation

Publication is written in English

Some studies do not describe the application of NLP in their study by only listing NLP as the used method, instead of describing its specific implementation. Additionally, some studies create their own ontology to perform NLP tasks, instead of using an established, domain-accepted ontology. Both approaches limit the generalizability of the study’s methods. Therefore, we defined the following exclusion criteria:

Implementation was not described

Implementation does not use an existing established ontology for encoding

Not published in a peer-reviewed journal (except for ACL and ACM publications)

In the second phase, both reviewers excluded publications where the developed NLP algorithm was not evaluated by assessing the titles, abstracts, and, in case of uncertainty, the Method section of the publication. In the third phase, both reviewers independently evaluated the resulting full-text articles for relevance. The reviewers used Rayyan [27] in the first phase and Covidence [28] in the second and third phases to store the information about the articles and their inclusion. In all phases, both reviewers independently reviewed all publications. After each phase the reviewers discussed any disagreement until consensus was reached.

Data extraction and categorization

Both reviewers categorized the implementations of the found algorithms and noted their characteristics in a structured form in Covidence. The objectives of the included studies and their associated NLP tasks were categorized by way of induction. The results were compared and merged into one result set.

We collected the following characteristics of the studies, based on a combination of TRIPOD [21], STROBE [22], RECORD [23], and STARD [24] statement elements (see Additional file 3): year, country, setting, objectives, evaluation methods, used NLP systems or algorithms, used terminology systems, size of datasets, performance measures, reference standard, language of the free-text data, validation methods, generalizability, operational use, and source code availability.

List of recommendations

Based on the findings of the systematic review and elements from the TRIPOD, STROBE, RECORD, and STARD statements, we formed a list of recommendations. The recommendations focus on the development and evaluation of NLP algorithms for mapping clinical text fragments onto ontology concepts and the reporting of evaluation results.

Results

The literature search generated a total of 2355 unique publications. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, we selected 256 publications for additional screening. Out of the 256 publications, we excluded 65 publications, as the described Natural Language Processing algorithms in those publications were not evaluated. The full text of the remaining 191 publications was assessed and 114 publications did not meet our criteria, of which 3 publications in which the algorithm was not evaluated, resulting in 77 included articles describing 77 studies. Reference checking did not provide any additional publications. The PRISMA flow diagram is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

The induction process resulted in eight categories and ten associated NLP tasks that describe the objectives of the papers: computer-assisted coding, information comparison, information enrichment, information extraction, prediction, software development and evaluation, and text processing. Our definitions of these NLP tasks and the associated categories are given in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Induced objective tasks with their definition and an example

| Induced NLP task(s) | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Concept detection 1 | Assign ontology concepts to phrases in free text (i.e., entity linking or annotation) | “Systolic blood pressure” can be represented as SNOMED-CT concept 271649006 | Systolic blood pressure (observable entity) | |

| Event detection | Detect events in free text | “Patient visited the outpatient clinic in January 2020” is an event of type Visit. |

| Relationship detection | Detect semantic relationships between concepts in free text | The concept Lung cancer in “This patient was diagnosed with recurrent lung cancer” is related to the concept Recurrence. |

| Text normalization | Transform free text into a single canonical form | “This patient was diagnosed with influenza last year.” becomes “This patient be diagnose with influenza last year.” |

| Text summarization | Create a short summary of free text and possible restructure the text based on this summary | “Last year, this patient visited the clinic and was diagnosed with diabetes mellitus type 2, and in addition to his diabetes, the patient was also diagnosed with hypertension” becomes “Last year, this patient was diagnosed with diabetes mellitus type 2 and hypertension”. |

| Classification | Assign categories to free text | A report containing the text “This patient is not diagnosed yet” will be assigned to the category Undiagnosed. |

| Prediction | Create a predictive model based on free text | Predict the outcome of the APACHE score based on the (free-text) content in a patient chart. |

| Identification | Identify documents (e.g., reports or patient charts) that match a specific condition based on the contents of the document | Find all patient charts that describe patients with hypertension and a BMI above 30. |

| Software development | Develop new or build upon existing NLP software | A new algorithm was developed to map ontology concepts to free text in clinical reports. |

| Software evaluation | Evaluate the effectiveness of NLP software | The mapping algorithm has an F-score of 0.874. |

1.Also known as Medical Entity Linking and Medical Concept Normalization

Table 2.

Induced objective categories with their definition and associated NLP task(s)

| Induced category | Induced NLP task(s) | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Computer-assisted coding | Concept detection | Perform semi-automated annotation (i.e., with a human in the loop) |

| Information comparison |

Concept detection Event detection Relationship detection |

Compare extracted structured information to information available in free-text form |

| Information enrichment |

Concept detection Event detection Relationship detection Text normalization Text summarization |

Extract structured information from free text and attach this new information to the source |

| Information extraction |

Concept detection Event detection Relationship detection |

Extract structured information from free text |

| Prediction |

Classification Prediction Identification |

Use structured information to classify free-text reports, predict outcomes, or identify cases |

|

Software development and evaluation |

Software development Software evaluation |

Develop new NLP software or evaluate new or existing NLP software |

| Text processing |

Text normalization Text summarization |

Transform free text into a new, more comprehensible form |

Table 3 lists the included publications with their first author, year, title, and country. Table 4 lists the included publications with their evaluation methodologies. The non-induced data, including data regarding the sizes of the datasets used in the studies, can be found as supplementary material attached to this paper.

Table 3.

Included publications and their first author, year, title, and country

| Author | Year | Country | Challenge | Induced objective | Data origin | Dataset | Data language | Used system | Term. Sys. | In use | Source code | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afshar | 2019 | USA | No | Information extraction | Clinical Data Warehouse Data | Own | English | New (+ existing) | UMLS (CPT, HCPCS, ICD-10, ICD10CM / ICD9CM, LOINC, MeSH, SNOMED-CT, RxNorm) | Not listed | No, only links to cTAKES source code | [29] |

| Alnazzawi | 2016 | UK | No | Information enrichment | PhenoCHF corpus 1 | Existing | English | Existing | UMLS | Not listed | Not applicable | [30] |

| Atutxa | 2018 | Spain | No | Information enrichment | EHR documents | Own | Spanish | New | ICD (SNOMED-CT for normalization) | Not yet, aim to embed it in human-supervised loop | Not listed | [31] |

| Barrett | 2013 | USA | No | Information extraction | Palliative care consult letters | Own | English | New | SNOMED CT | Not listed | No, but planned | [32] |

| Becker | 2016 | Germany | No | Information extraction | ShARe/CLEF corpus (2013) 2 | Existing | German | Existing | SNOMED CT (English), UMLS (German) | Not yet, still under development | Not applicable | [33] |

| Becker | 2019 | Germany | No | Information extraction | Clinical notes of patients with known colorectal cancer | Own | German | New (+ existing) | UMLS | Yes, led to improved quality of care for colorectal patients | Not listed | [34] |

| Bejan | 2015 | USA | No | Information extraction | Discharge summaries and i2b2/VA challenge dataset (2010) 3 | Own + Existing | English | Existing | UMLS | No | Not applicable | [35] |

| Castro | 2010 | Spain | No | Information extraction | Clinical notes with ‘most relevant information’ | Own | Spanish | Existing | SNOMED CT | Not listed | Not applicable | [36] |

| Catling | 2018 | UK | No | Software development and evaluation | MIMIC-III dataset 4 | Existing | English | New | ICD-9-CM | Not listed | Not listed | [37] |

| Chapman | 2004 | USA | No | Information extraction | Emergency department reports | Own | English | Existing | UMLS | Not listed | Not applicable | [38] |

| Chen | 2016 | USA | No | Information enrichment | Discharge summaries and progress notes | Own | English | New (+ existing) | UMLS | Not listed | Not listed | [39] |

| Chiaramello | 2016 | Italy | No | Information extraction | Clinical notes (cardiology, diabetology, hepatology, nephrology, and oncology) | Own | Italian | Existing | UMLS | Not listed | Not applicable | [40] |

| Chodey | 2016 | USA | SemEval (2014) | Information extraction | ICU Data: Discharge summaries, ECG, echo, and radiology | Existing | English | New (+ existing) | UMLS | Not listed | Not listed | [41] |

| Chung | 2005 | USA | No | Information extraction | Echocardiogram reports | Own | English | New (+ existing) | UMLS | Not yet, it will be used to populate a registry | Not listed | [42] |

| Combi | 2018 | Italy | No | Information extraction | VigiSegn (adverse drug reactions) reports | Own | Italian + English | New | MedDRA | Yes, implemented in VigiFarmaco | Pseudocode | [43] |

| De Bruijn | 2011 | Canada | i2b2/VA (2010) | Information extraction | Hospital discharge summaries and progress reports | Existing | English | New (+ existing) | UMLS | Not listed | Not listed | [44] |

| Deisseroth | 2019 | USA | No | Information extraction | Six sets of real patient data from four different medical centers. | Own | English | New | HPO | Not listed | Yes | [45] |

| Demner-Fushman | 2017 | USA | No | Software development and evaluation | BioScope 5, NCBI disease corpus 6, i2b2/VA challenge corpus (2010) 3, ShARe corpus 7, LHC test collection (biological/clinical journal abstracts) | Existing | English | New (+ existing) | UMLS | Yes, used in other papers identified in literature search | Yes | [46] |

| Divita | 2014 | USA | Parts: i2b2/VA (2010) | Software development and evaluation | Randomly selected clinical records from the most frequent document types | Own | English | New | UMLS (level 0 + 9) | Yes, used by VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure | Yes | [47] |

| Duarte | 2018 | Portugal | No | Information enrichment | Death certificates, clinical bulletins, and autopsy reports | Own | Portuguese | New | ICD-10 | Yes, used by Portugese Ministry of Health for near real-time death cause surveillance | Not listed | [48] |

| Falis | 2019 | UK | No | Information extraction | MIMIC-III dataset 4 | Existing | English | New | ICD-9 | Not listed | Not listed | [49] |

| Ferrão | 2013 | Portugal | No | Information enrichment | Inpatient adult episodes from the EHR | Own | Portuguese | New | ICD-9-CM | Not listed | Not listed | [50] |

| Gerbier | 2011 | France | No | Information extraction | Computerized emergency department medical records | Own | French | New | ICD-10, CCAM, SNOMED CT, ATC, MeSH, ICPC-2, DCR | Not yet, will be integrated into a CDSS | Not listed | [51] |

| Goicoechea Salazar | 2013 | Spain | No | Information enrichment | Diagnostic text from patient records | Own | Spanish | New | ICD-9-CM | Not listed | Not listed | [52] |

| Hamid | 2013 | USA | No | Classification | Notes of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans from the VA national clinical database | Own | English | Existing | UMLS | Not listed | Not applicable | [53] |

| Hassanzadeh | 2016 | Australia | No | Information extraction | ShARe/CLEF corpus (2013) 2 | Existing | English | Existing | UMLS, SNOMED CT | Not applicable | Not applicable | [54] |

| Helwe | 2017 | Lebanon | No | Computer-assisted coding | MIMIC-III dataset | Existing | English | New | UMLS, ICD | Not listed | Not listed | [55] |

| Hersh | 2001 | USA | No | Information enrichment | Radiology image reports | Own | English | Existing | UMLS | No, still in development/testing | Pseudocode | [56] |

| Hoogendoorn | 2015 | Netherlands | No | Prediction | Consultation notes of patients in a primary care setting | Own | Dutch | New | SNOMED-CT, UMLS, ICPC | Not listed | Not listed | [57] |

| Jindal | 2013 | USA | i2b2 (2012) | Information extraction | i2b2 challenge corpus (2012) 8 | Existing | English | New (+ existing) | UMLS, SNOMED CT, MeSH | Not listed | Not listed | [58] |

| Kang | 2009 | Korea | No | Information extraction | Discharge summaries | Own | Korean | New | KOMET, UMLS | Not listed | Not listed | [59] |

| Kersloot | 2019 | Netherlands | No | Information extraction | (Non-small cell) Lung cancer charts | Own | English | New (+ existing) | SNOMED CT | Not listed | Yes | [60] |

| König | 2019 | Germany | No | Software development and evaluation | Discharge letters from BASE-II study | Own | German | New (+ existing) | Wingert-Nomenclature | No, still has to prove its value | Not listed | [61] |

| Li | 2015 | USA | No | Information comparison | Clinical notes and discharge prescription lists | Own | English | New (+ existing) | UMLS, SNOMED CT, RxNorm | Not yet, plans to move to production | Pseudocode | [62] |

| Li | 2019 | USA | No | Information extraction | EHR notes | Own | English | New (+ existing) | UMLS, SNOMED CT, MedDRA | Not listed | Not listed | [63] |

| Lingren | 2016 | USA | No | Classification | Structured and unstructured data from two EHR databases | Own | English | New (+ existing) | UMLS, ICD-9, RxNorm | Not listed | Not listed | [12] |

| Liu | 2019 | USA | No | Information extraction | Clinical notes from different institutions + PubMed Case report abstracts | Own + Existing | English | Existing | HPO | Not listed | Not applicable | [64] |

| Lowe | 2009 | USA | No | Information extraction | Single-specimen pathology reports | Own | English | Existing | UMLS, SNOMED CT | Not listed | Not applicable | [65] |

| Luo | 2014 | USA | No | Information extraction | Pathology reports | Own | English | New (+ existing) | UMLS, SNOMED CT | Yes, currently working on project in multiple hospitals | Not listed | [66] |

| Meystre | 2006 | USA | No | Information enrichment | Clinical documents form adult inpatients in a cardiovascular unit | Own | English | New (+ existing) | UMLS (level 0), SNOMED CT | Not yet, testing in practice | Not listed | [67] |

| Meystre | 2010 | USA | i2b2 (2009) | Information extraction | i2b2 challenge dataset (2009) 9 | Existing | English | New | UMLS | Not yet, possible integration in research infrastructure | Not listed | [68] |

| Minard | 2011 | France | i2b2/VA (2010) | Information extraction | i2b2/VA challenge corpus (2010) 3 | Existing | English | New (+ existing) | UMLS | Not listed | Not listed | [69] |

| Mishra | 2019 | USA | No | Information extraction | Clinical notes from NIH Clinical Center data warehouse | Own | English | Existing | UMLS, HPO | Not listed | Not applicable | [70] |

| Nguyen | 2018 | Australia | No | Computer-assisted coding | Hospital progress notes | Own | English | New (+ existing) | SNOMED CT, ICD-10-AM | Not listed | Not listed | [71] |

| Oellrich | 2015 | UK | No | Information extraction | PubMed abstracts, clinical trial information, i2b2/VA challenge corpus (2010) 3, SHARE/CLEF (2013) 2 | Existing | English | Existing | UMLS | Not listed | Not applicable | [72] |

| Patrick | 2011 | Australia | i2b2/VA (2010) | Information extraction | i2b2/VA challenge corpus (2010) 3 | Existing | English | New | UMLS, SNOMED CT | Not listed | Not listed | [73] |

| Pérez | 2018 | Spain | No | Text processing | Spontaneous DTs randomly selected entries | Own | Spanish | New | ICD | Not listed | Not listed | [74] |

| Reátegui | 2018 | Canada | No | Information extraction | i2b2 challenge corpus (2008) 10 | Existing | English | New (+ existing) | UMLS, SNOMED CT, RxNorm | Not listed | Not listed | [75] |

| Roberts | 2011 | USA | i2b2/VA (2010) | Information extraction | i2b2/VA challenge corpus (2010) 3 | Existing | English | New (+ existing) | UMLS, ICD-9 | Not listed | Not listed | [76] |

| Rousseau | 2019 | USA | No | Information comparison | ED encounters for patients with headaches who received head CT | Own | English | Existing | UMLS: SNOMED CT, RadLex | Not listed | Not applicable | [77] |

| Savova | 2010 | USA | i2b2 (2006, 2008) | Information extraction | Subset of clinical notes from the EMR | Own | English | New (+ existing) | UMLS, SNOMED CT, RxNorm | Yes, used in other papers identified in literature search | Yes | [78] |

| Shivade | 2015 | USA | i2b2/UTHealth (2014) | Classification | i2b2 challenge corpus (2014) 11 | Existing | English | Existing | UMLS | Not listed | Not applicable | [11] |

| Shoenbill | 2019 | USA | No | Information extraction | EHR notes from hypertension patients | Own | English | Existing | UMLS, SNOMED CT | Not listed | Not applicable | [79] |

| Sohn | 2014 | USA | No | Information extraction | Clinical notes with medication mentions | Own | English | New | RxNorm | Not listed | Yes | [80] |

| Solti | 2008 | USA | No | Information enrichment | Cardiology ambulatory progress notes | Own | English | Existing | UMLS | Not listed | Not applicable | [81] |

| Soriano | 2019 | Spain | No | Information extraction | clinical emergency discharge reports | Own | Spanish | New | SNOMED CT | Not yet | Yes | [82] |

| Soysal | 2018 | USA | Parts: i2b2 (2009 + 2010), ShARe/CLEF (2013), Sem-EVAL (2014) | Software development and evaluation | Discharge summaries from the i2b2/VA challenge corpus (2010) 3, outpatient clinic visit notes, mock clinical documents | Own + Existing | English | New | UMLS | Yes, used by various institutions and industrial entities | Yes | [83] |

| Spasić | 2015 | UK | No | Information extraction | MRI reports of patients | Own | English | New (+ existing) | TRAK, UMLS, MEDCIN, RadLex | Not listed | Yes | [84] |

| Strauss | 2013 | USA | No | Information extraction | Pathology reports of breast and prostate cancer patients | Own | English | New | SNOMED CT | Not listed | Yes | [85] |

| Sung | 2018 | Taiwan | No | Information extraction | Cases of adult patients with AIS | Own | English | Existing | UMLS | Not listed | Not applicable | [86] |

| Tchechmedjiev | 2018 | France | No | Information extraction | Quaero (French MEDLINE abstract titles + EMEA drug labels) + CépiDC (ICD-10 coding of death certificates) | Existing | French | New (+ existing) | UMLS terminologies (ICD-10) | Yes, available in SIFR BioPortal | Yes | [87] |

| Ternois | 2018 | France | No | Classification | Endoscopy reports written between 2015 and 2016 | Own | French | New | CCAM | Not listed | Not listed | [88] |

| Travers | 2004 | USA | No | Information extraction | Chief complaint text entries for all emergency department visits | Own | English | New | UMLS | Not listed | Not listed | [89] |

| Tulkens | 2019 | Belgium | No | Information extraction | i2b2/VA challenge corpus (2010) 3 | Existing | English | New (+ existing) | UMLS | Not listed | Yes | [90] |

| Usui | 2018 | Japan | No | Prediction | Electronic medication history data from pharmacy | Own | Japanese | New | ICD-10 | Not yet, expect to use it | Not listed | [91] |

| Valtchinov | 2019 | USA | No | Classification | Radiology reports, emergency department notes + other clinical reports | Own | English | Existing | SNOMED CT, RadLex | Not listed | Not applicable | [92] |

| Wadia | 2018 | USA | No | Classification | Chest CT reports | Own | English | Existing | SNOMED CT, UMLS | Not listed | Not applicable | [93] |

| Walker | 2019 | USA | No | Information extraction | Treatment sites from EMR | Own | English | New | UMLS | Not listed | Not listed | [94] |

| Xie | 2019 | China | No | Information extraction | MIMIC-III dataset 4 | Existing | English | New | ICD-9-CM, ICD-10 | Not listed | Not listed | [95] |

| Xu | 2011 | USA | No | Classification | CRC patient cases from the Synthetic Derivative database | Own | English | Existing | UMLS | No, still under development | Not applicable | [96] |

| Yadav | 2013 | USA | No | Prediction | Emergency department CT imaging reports | Own | English | Existing | UMLS | Not listed | Yes, command line command | [97] |

| Yao | 2019 | USA | No | Prediction | i2b2 challenge corpus (2008) 10 | Existing | English | New (+ existing) | UMLS | Not listed | Part (Sorl) | [98] |

| Zeng | 2018 | USA | No | Classification | Progress notes and breast cancer surgical pathology reports | Own | English | New (+ existing) | UMLS | Not listed | Not listed | [99] |

| Zhang | 2013 | USA | No | Information extraction | i2b2/VA challenge corpus (2010) 3 and GENIA corpus (MEDLINE abstracts) | Existing | English | New | UMLS | Not listed | Not listed | [100] |

| Zhou | 2006 | USA | No | Information extraction | Records of patients with breast complaints | Own | English | New | UMLS | No, still under development | Not listed | [101] |

| Zhou | 2011 | USA | No | Software development and evaluation | COPD and CAD patients | Own | English | New | SNOMED CT, RxNorm, UMLS, PPL, MDD, HL7 value sets | Yes, described in other paper (103]) | Not listed | [102] |

| Zhou | 2014 | USA | No | Information extraction | Admission notes and discharge summaries | Own | English | Existing | SNOMED CT, HL7 RoleCodes | Not listed | Not applicable | [103] |

1. PhenoCHF corpus: narrative reports from electronic health records (EHRs) and literature articles

2. ShARe/CLEF corpus (2013): narrative clinical reports

3. i2b2/VA challenge dataset (2010): discharge summaries and progress reports

4. MIMIC-III dataset: demographics, vital sign measurements, laboratory test results, procedures, medications, caregiver notes, imaging reports, and mortality

5. BioScope corpus: medical free texts, biological full papers and biological scientific abstracts

6. NCBI disease corpus: PubMed abstracts

7. ShARe corpus: deidentified clinical free-text notes from the MIMIC II database

8. i2b2 challenge corpus (2012): discharge summaries

9. i2b2 challenge dataset (2009): de-identified hospital discharge summaries

10. i2b2 challenge corpus (2008): discharge summaries of overweight and diabetic patients

11. i2b2 challenge corpus (2014): longitudinally ordered clinical notes from three cohorts of diabetic patients

Table 4.

Included publications and their evaluation methodologies

| Author | Year | Ref. std. | Validation | External | Generalizability a | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afshar | 2019 | Existing EHR data | Hold-out validation (train, test, development) | No | No, validation is needed | [29] |

| Alnazzawi | 2016 | Existing annotated corpus | External | ShARe/CLEF, NCBI disease, Heart failure and pulmonary embolism corpora | Yes, achieves competitive performance on other corpora | [30] |

| Atutxa | 2018 | Manual retrospective review | Hold-out validation (train, test, development) | No | Yes, easily portable to other languages | [31] |

| Barrett | 2013 | Manual annotations | 10-fold cross validation | Multiple datasets (different provider) | Yes, expect that it is generalizable | [32] |

| Becker | 2016 | Existing annotated corpus | Not used | No | Not listed | [33] |

| Becker | 2019 | Manual annotations | Hold-out validation (train, test, development) | No | Not listed | [34] |

| Bejan | 2015 | Manual annotations | External | i2b2 data (2010) | Yes, good performance on the i2b2 dataset, even though not optimized on it | [35] |

| Castro | 2010 | Manual annotations | Not used | No | Not listed | [36] |

| Catling | 2018 | Existing annotated corpus | Hold-out validation (train, test, development) | No | Not listed | [37] |

| Chapman | 2004 | Manual annotations | Not used | No | Yes, generalizable to other domains within and outside of bio surveillance | [38] |

| Chen | 2016 | Manual annotations | 10-fold cross validation | No | Not listed | [39] |

| Chiaramello | 2016 | Manual annotations | Not used | No | Not listed | [40] |

| Chodey | 2016 | Existing annotated corpus | Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Not listed | [41] |

| Chung | 2005 | Manual annotations | Hold-out validation (train, test) | Reports from a second hospital | Not listed | [42] |

| Combi | 2018 | Manual annotations | Not used | No | Not listed | [43] |

| deBruijn | 2011 | Existing annotated corpus | 15-fold cross validation | No | Not listed | [44] |

| Deisseroth | 2019 | Manual annotations | Hold-out validation (train, test) | Data from a second hospital | Yes, it can be immediately incorporated into clinical practice | [45] |

| Demner-Fushman | 2017 | Existing annotated corpus | External | Multiple datasets | Not listed | [46] |

| Divita | 2014 | Manual annotations | Not used | No | Not listed | [47] |

| Duarte | 2018 | Manual annotations | Hold-out validation (train, test) | Second dataset | Not listed | [48] |

| Falis | 2019 | Existing annotated corpus | Hold-out validation (train, test, development) | No | Yes, method is not specific to an ontology, and could be used for a graph of any formation | [49] |

| Ferrão | 2013 | Existing EHR data | Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Not listed | [50] |

| Gerbier | 2011 | Manual annotations | Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Yes, it could also serve other types of clinical decision support systems | [51] |

| Goicoechea Salazar | 2013 | Manual annotations | Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Not listed | [52] |

| Hamid | 2013 | Manual annotations | 10-fold cross validation | No | Possible, the classifier may be applicable in academic hospital samples | [53] |

| Hassanzadeh | 2016 | Existing annotated corpus | Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Not applicable | [54] |

| Helwe | 2017 | Existing annotated corpus | Hold-out validation (train, test, development) | No | Not listed | [55] |

| Hersh | 2001 | Manual annotations | Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Not listed | [56] |

| Hoogendoorn | 2015 | Existing EHR data | 5-fold cross validation | No | Not listed | [57] |

| Jindal | 2013 | Existing annotated corpus | Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Yes, broad applicability | [58] |

| Kang | 2009 | Manual annotations | Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Yes, extensible to other languages | [59] |

| Kersloot | 2019 | Manual annotations | Hold-out validation (development, test) | No | Possible, but external validation is needed | [60] |

| König | 2019 | Existing EHR data | Not used | No | Still to be tested | [61] |

| Li | 2015 | Manual annotations | 10-fold cross validation | No | Not listed | [62] |

| Li | 2019 | Existing annotated corpus | Hold-out validation (train, test, development) | No | Not listed | [63] |

| Lingren | 2016 | Manual annotations | Hold-out validation (train, test, development) | No | Not listed | [12] |

| Liu | 2019 | Manual annotations | Not used | No (but multiple datasets / non-trained) | No, limited because of NYP/CUIMC and Mayo notes. | [64] |

| Lowe | 2009 | Manual retrospective review | Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Yes, has the potential to index other classes of clinical documents | [65] |

| Luo | 2014 | Existing EHR data | 10-fold cross validation | No | No, challenging, not currently working on it | [66] |

| Meystre | 2006 | Manual retrospective review | Not used | No | Not listed | [67] |

| Meystre | 2010 | Existing annotated corpus | Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Not listed | [68] |

| Minard | 2011 | Existing annotated corpus | Hold-out validation (train, test, development) | No | Not listed | [69] |

| Mishra | 2019 | Manual annotations | Not used | No | Not listed | [70] |

| Nguyen | 2018 | Existing EHR data | Not listed | No | Not listed | [71] |

| Oellrich | 2015 | Existing annotated corpus | External | Multiple datasets | Not listed | [72] |

| Patrick | 2011 | Existing annotated corpus | 10-fold cross validation | No | Yes, adaptable to different requirements in clinical information extraction and classification by choosing relevant feature sets | [73] |

| Pérez | 2018 | Existing annotated corpus | Hold-out validation (train, test, development) | No | Yes, extensible to different hospital-sections and hospitals | [74] |

| Reátegui | 2018 | Existing annotated corpus | Not used | No | Not listed | [75] |

| Roberts | 2011 | Existing annotated corpus | Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Not listed | [76] |

| Rousseau | 2019 | Manual annotations | Not used | No | Not listed | [77] |

| Savova | 2010 | Manual annotations | 10-fold cross validation | No | Yes, implemented in several applications | [78] |

| Shivade | 2015 | Manual annotations | Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Not listed | [11] |

| Shoenbill | 2019 | Manual annotations | Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Yes, can allow further evaluation and improvement in care delivery models and treatment approaches to multiple chronic illnesses | [79] |

| Sohn | 2014 | Manual annotations | Hold-out validation (train, test, development) | No | Yes, with adaptions: create flexible mechanism for adaptation process | [80] |

| Solti | 2008 | Manual annotations | Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Not listed | [81] |

| Soriano | 2019 | Manual annotations | Not listed | No | Not listed | [82] |

| Soysal | 2018 | Existing annotated corpus | Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Yes, can be used to quickly develop customized clinical information extraction pipelines | [83] |

| Spasić | 2015 | Manual annotations | Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Not listed | [84] |

| Strauss | 2013 | Manual annotations | Not used | No | Yes, can be shared between institutions and used to support clinical + epidemiological research | [85] |

| Sung | 2018 | Manual annotations | Not listed | No | Not listed | [86] |

| Tchechmedjiev | 2018 | Existing annotated corpus | Hold-out validation (train, test, development) | No | Yes, but not universally | [87] |

| Ternois | 2018 | Existing EHR data | 5-fold cross validation + Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Not listed | [88] |

| Travers | 2004 | Manual retrospective review | Not used | No | Not listed | [89] |

| Tulkens | 2019 | Existing annotated corpus | Hold-out validation (train, test, development) | No | Not listed | [90] |

| Usui | 2018 | Manual annotations | Not used | No | Not listed | [91] |

| Valtchinov | 2019 | Manual annotations | Not used | No | No | [92] |

| Wadia | 2018 | Manual annotations | Not used | No | Not listed | [93] |

| Walker | 2019 | Manual retrospective review | Hold-out validation (development, test) | No | Yes, it can be incorporated in institutional data warehouse | [94] |

| Xie | 2019 | Existing annotated corpus | Hold-out validation (train, test, development) | No | Not listed | [95] |

| Xu | 2011 | Manual annotations | Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Yes, generable approach to combine information from heterogeneous data sources in EHRs | [96] |

| Yadav | 2013 | Manual annotations | Not used | No | Yes, should be broadly applicate to outcomes of clinical interest | [97] |

| Yao | 2019 | Existing annotated corpus | Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Not listed | [98] |

| Zeng | 2018 | Manual annotations | 5-fold cross validation + Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Yes, potential to be replicated | [99] |

| Zhang | 2013 | Existing annotated corpus | External | Two different sets with same settings | Yes, can be adapted to different semantic categories and text genres | [100] |

| Zhou | 2006 | Manual annotations | 5-fold cross validation | No | Not listed | [101] |

| Zhou | 2011 | Manual retrospective review | Hold-out validation (train, test) | No | Not listed | [102] |

| Zhou | 2014 | Manual annotations | Not used | No | Not listed | [103] |

a As reported by authors

Table 5 summarizes the general characteristics of the included studies and Table 6 summarizes the evaluation methods used in these studies. In all 77 papers, we found twenty different performance measures (Table 7).

Table 5.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Description | n (%) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Main objective | ||

| Information extraction | 45 (58%) | [29, 32–36, 38, 40–45, 49, 51, 58–60, 63–66, 68–70, 72, 73, 75, 76, 78–80, 82, 84–87, 89, 90, 94, 95, 100, 101, 103, 104] |

| Information enrichment | 9 (12%) | [30, 31, 39, 48, 50, 52, 56, 67, 81] |

| Classification | 8 (10%) | [11, 12, 53, 88, 92, 93, 96, 99] |

| Software development and evaluation | 6 (7.8%) | [37, 46, 47, 61, 83, 102] |

| Prediction | 4 (5.2%) | [57, 91, 97, 98] |

| Information comparison | 2 (2.6%) | [62, 77] |

| Computer-assisted coding | 2 (2.6%) | [55, 71] |

| Text processing | 1 (1.3%) | [74] |

| Part of challenge | ||

|

i2b2 (Informatics for Integrating Biology and the Bedside) |

10 (13%) | [11, 44, 47, 58, 68, 69, 73, 76, 78, 83] |

| Entire system | 8 (10%) | [11, 44, 58, 68, 69, 73, 76, 78] |

| Parts of the system | 2 (2.6%) | [47, 83] |

| SemEval (Semantic Evaluation) | 2 (2.6%) | [41, 83] |

| Entire system | 1 (1.3%) | [41] |

| Parts of the system | 1 (1.3%) | [83] |

|

ShARe/CLEF (Shared Annotated Resources/Conference and Labs of the Evaluation Forum) |

1 (1.3%) | [83] |

| Parts of the system | 1 (1.3%) | [83] |

| Dataset: language | ||

| English | 60 (78%) | [11, 12, 29, 30, 32, 35, 37–39, 41–47, 49, 53, 55, 56, 58, 60, 62–73, 75–81, 83–86, 89, 90, 92–104] |

| Spanish | 5 (6.5%) | [31, 36, 52, 74, 82] |

| French | 3 (3.9%) | [51, 87, 88] |

| German | 3 (3.9%) | [33, 34, 61] |

| Italian | 2 (2.6%) | [40, 43] |

| Portuguese | 2 (2.6%) | [48, 50] |

| Dutch | 1 (1.3%) | [57] |

| Japanese | 1 (1.3%) | [91] |

| Korean | 1 (1.3%) | [59] |

| Dataset: Origin | ||

| Data present in institute | 55 (71%) | [12, 29, 31, 32, 34–36, 38–40, 42, 43, 45, 47, 48, 50–53, 56, 57, 59–67, 70, 71, 74, 77–86, 88, 89, 91–94, 96, 97, 99, 101–103] |

| Existing dataset | 25 (33%) | [11, 30, 33, 35, 37, 41, 44, 46, 49, 55, 58, 64, 68, 69, 72, 73, 75, 76, 83, 87, 90, 95, 98, 100, 104] |

| Included reference to dataset | 21 (27%) | [11, 30, 35, 37, 41, 44, 46, 49, 55, 58, 64, 72, 75, 76, 83, 87, 90, 95, 98, 100, 104] |

| Training of algorithm | ||

| Trained | 47 (61%) | [11, 12, 29, 31, 32, 34, 37, 39, 41, 42, 44, 45, 48–53, 55–59, 62, 63, 65, 66, 68, 69, 73, 74, 76, 78–84, 87, 88, 90, 95, 96, 98, 99, 104] |

| Not listed | 3 (3.9%) | [30, 101, 102] |

| Development of algorithm | ||

| Use of development set | 16 (21%) | [12, 29, 31, 34, 37, 49, 55, 60, 63, 69, 74, 80, 87, 90, 94, 95] |

| Not listed | 4 (5.2%) | [30, 82, 83, 101] |

| Used NLP system or algorithm | ||

| New NLP system or algorithm | 29 (38%) | [31, 32, 37, 43, 45, 47–52, 55, 57, 59, 68, 73, 74, 80, 82, 83, 85, 88, 89, 91, 94, 95, 100–102] |

| New NLP system or algorithm with existing components | 25 (33%) | [12, 29, 34, 39, 41, 42, 44, 46, 58, 60–63, 66, 67, 69, 71, 75, 76, 78, 84, 87, 90, 98, 99] |

| Existing NLP system or algorithm | 23 (30%) | [11, 30, 33, 35, 36, 38, 40, 53, 56, 64, 65, 70, 72, 77, 79, 81, 86, 93, 96, 97, 103, 104] |

| Use in practice | ||

| Plans to implement / still under development and testing | 12 (16%) | [31, 33, 51, 56, 62, 66–68, 82, 91, 96, 101] |

| Implemented in practice | 10 (13%) | [34, 42, 43, 46–48, 78, 83, 87, 102] |

| Availability of code | ||

| Published algorithm or source code | 15 (20%) | [31, 45–47, 60, 78, 80, 82–85, 87, 90, 97, 98] |

| Pseudocode in manuscript | 3 (3.9%) | [43, 56, 62] |

| Planning to publish algorithm or source code | 1 (1.3%) | [32] |

| Not applicable, used an existing system | 20 (26%) | [11, 30, 33, 35, 36, 38, 40, 53, 64, 65, 70, 72, 77, 79, 81, 86, 93, 96, 103, 104] |

Table 6.

Evaluation methods of the included studies

| Description | n (%) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Evaluation: Reference standard | ||

| Manual annotations | 40 (52%) | [11, 12, 32, 34–36, 38–40, 42, 43, 45, 47, 48, 51–53, 56, 59, 60, 62, 64, 70, 77–82, 84–86, 91–93, 96, 97, 99, 101, 103] |

| Existing annotated corpus | 24 (31%) | [30, 33, 37, 41, 44, 46, 49, 55, 58, 63, 68, 69, 72–76, 83, 87, 90, 95, 98, 100, 104] |

| Existing EHR data | 7 (9.1%) | [29, 50, 57, 61, 66, 71, 88] |

| Manual retrospective review | 6 (7.8%) | [31, 65, 67, 89, 94, 102] |

| Evaluation: Validation | ||

| Hold-out validation | 40 (52%) | [11, 12, 29, 31, 34, 37, 41, 42, 45, 48–52, 55, 56, 58–60, 63, 65, 68, 69, 74, 76, 79–81, 83, 84, 87, 88, 90, 94–96, 98, 99, 102, 104] |

| Cross-validation | 12 (16%) | [32, 39, 44, 53, 57, 62, 66, 73, 78, 88, 99, 101] |

| External validation | 9 (12%) | [30, 32, 35, 42, 45, 46, 48, 72, 100] |

| Solely external validation | 5 (6.5%) | [30, 35, 46, 72, 100] |

| In addition to another type of validation | 4 (5.2%) | [32, 42, 45, 48] |

| Not performed or not listed | 22 (29%) | [33, 36, 38, 40, 43, 47, 61, 64, 67, 70, 71, 75, 77, 82, 85, 86, 89, 91–93, 97, 103] |

| Generalizability | ||

| Claimed | 23 (30%) | [30–32, 35, 38, 45, 49, 51, 58, 59, 65, 73, 74, 78–80, 83, 85, 87, 94, 96, 97, 100] |

| Externally validated | 5 (6.5%) | [30, 32, 35, 45, 100] |

| Comparison | ||

| Compared to other existing algorithms or models | 24 (31%) | [30, 35, 39, 45–47, 49, 58, 60, 63, 64, 72, 75, 80, 83, 87, 90, 94, 95, 98–101, 104] |

| Tested difference in outcomes for statistical significance | 4 (5.2%) | [35, 39, 60, 63] |

Table 7.

Performance measures used in the included studies

| Description | Formula | n (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confusion Matrix |

Lists the True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), False Positives (FP), False Negatives (FN), and the Total (n) amount in a 2 × 2 contingency Table. TP: Text annotated with ontology concept when ontology concept is present in reference standard TN: Text not annotated with ontology concept when ontology concept is absent in reference standard FP: Text annotated with ontology concept when ontology concept is absent in reference standard FN: Text not annotated with ontology concept when ontology concept is present in reference standard |

12 (16%) | [34, 44, 47, 51, 56, 58, 60, 61, 84, 87, 91, 93] |

| Performance measures | |||

| Recall | 68 (88%) | [11, 12, 29–31, 33–53, 56–58, 60–64, 66–73, 75–88, 90–94, 96, 99–104] | |

| Precision | 66 (86%) | [11, 12, 29–31, 33–36, 38–51, 53, 56–58, 60–73, 75–88, 90, 91, 93, 94, 96, 99–104] | |

| F-score | 57 (74%) | [11, 12, 30, 31, 33–36, 39–41, 44, 46–50, 52, 53, 55, 57–63, 66–73, 75–80, 82–84, 86–88, 90, 91, 95, 96, 98–100, 102–104] | |

| Accuracy | 11 (14%) | [30, 32, 34, 41, 48, 52, 67, 74, 78, 92, 96] | |

| Specificity | 6 (7.8%) | [29, 34, 85, 92, 93, 96] | |

| AUC | Not applicable | 5 (6.5%) | [29, 39, 57, 95, 99] |

| Kappa | 3 (3.9%) | [85, 89, 97] | |

| Processing time | Not applicable | 3 (3.9%) | [32, 47, 83] |

| Negative Predictive Value | 3 (3.9%) | [29, 85, 93] | |

| False Positive Rate | 1 (1.3%) | [34] | |

| False Negative Rate | 1 (1.3%) | [34] | |

| Information entropy | 1 (1.3%) | [64] | |

| Mean Reciprocal Rank | 1 (1.3%) | [74] | |

| Initial annotator agreement | Not applicable | 1 (1.3%) | [79] |

| Match/no match (%) | Not applicable | 1 (1.3%) | [89] |

| Overgeneration | 1 (1.3%) | [93] | |

| Undergeneration | 1 (1.3%) | [68] | |

| Error | 1 (1.3%) | [68] | |

| Fallout | 1 (1.3%) | [68] | |

| Mean Standard Error | 1 (1.3%) | [57] | |

Discussion

In this systematic review, we reviewed the current state of NLP algorithms that map clinical text fragments onto ontology concepts with regard to their development and evaluation, in order to propose recommendations for future studies.

Main findings and recommendations

We identified 256 studies that reported on the development of such algorithms, of which 68 did not evaluate the performance of the system. We included 77 studies. Many publications did not report their findings in a structured way, which made it challenging to extract all the data in a reliable manner. We discuss our findings and recommendations in the following five categories: Used NLP systems and algorithms, Used data, Evaluation and validation, Presentation of results, and Generalizability of results. A checklist for determining if the recommendations are followed in the reporting of an NLP study is added as supplementary material to this paper.

Used NLP systems and algorithms

A variety of NLP systems are used in the reviewed studies. Researchers use existing systems (n = 29, 38%), develop new systems with existing components (n = 25, 33%), or develop a completely new system (n = 23, 30%). Most studies, however, do not publish their (adapted) source code (n = 57, 74%), and a description of the algorithm in the final publication is often not detailed enough to replicate it. To ensure reproducibility, implementation details, including details on data processing, and preferably the source code should be published, allowing other researchers to compare their implementations or to reproduce the results. Based on these findings, we formulated three recommendations (Table 8).

Table 8.

Recommendation regarding the use of systems and algorithms

|

1. Describe the system or algorithm that is used or the system that is developed for the specific NLP task. 1. When an existing NLP system or algorithm is used, describe how it is set up, how it is implemented in practice, and if and how the implementation differs from the original implementation. 2. When a new system is developed, describe the components and features used in the system, and preferably include a flow chart that explains how these elements work together. 2. Include the source code of the developed algorithm as supplementary material to the publication or upload the source code to a repository such as GitHub. 3. Specify which ontologies are used in the encoding task, including the version of the ontology. 1. If a new ontology is developed for the encoding task, report on the development and content of the ontology and rationale for the development of a new ontology instead of the use of an existing one. The MIRO guidelines could be used to structure the report [105]. |

Used data

Most authors evaluate their algorithms with manual annotations (n = 40, 52%) and use data present in their institutions (n = 55, 71%). However, it is not clear what these datasets consist of. Most studies describe the data as ‘reports’, ‘notes’, or ‘summaries’, but do not list the contents or example rows from the dataset. It is, therefore, not clear what types of patients and what specific types of data are included, making the study hard to reproduce. Finally, we found a wide range of dataset sizes and formats. The training datasets, for example, ranged from 10 clinical notes to 636.439 discharge reports. The use of small datasets can result in an overfitted algorithm that either performs well on the dataset, but not on an external dataset, or performs poorly, for the algorithm was only trained on a specific type of data. More difficult recognition tasks require more data, and therefore sample size planning is recommended [106]. To improve the description and availability of datasets used in NLP studies, we formulated three recommendations (Table 9).

Table 9.

Recommendation regarding the use of data

|

1. To ensure that new algorithms can be compared against your system, aim to publish the used training, development, and validation data in a data repository. 1. In case the data cannot be published, determine if the data can be accessed on request or can be used in a federated learning approach (i.e., a learning process in which the data owners collaboratively train a model in which process any data owner does not expose the data to others [107]). 2. In case a reference standard is used, include information about the origin of the data (external dataset, subset of the dataset) and the characteristics of the data in the dataset. If possible, reference the dataset using a DOI or URL. 3. If an external dataset is used, give a short description of the data present in the dataset and reference the source of the dataset. |

Evaluation and validation

Evaluation of the algorithm determines its performance on the dataset, and validation determines if the algorithm is not overfitted on that dataset and thus if the algorithm might work on other datasets as well. Over one-fourth of the studies (n = 68, 27%) that we identified did not evaluate their algorithms. In addition, 22 included studies (29%) did not validate the developed algorithm. A statement claiming that an algorithm can be used in clinical practice can be questioned if the algorithm has not been evaluated and validated. Across all studies, 20 performance measures were used. To harmonize evaluation and validation efforts, we formulated three recommendations (Table 10).

Table 10.

Recommendation regarding the evaluation and validation of Natural Language Processing algorithms

|

1. Perform an evaluation using generic (i.e., precision, recall, and F-score) performance measures and appropriate aspects of evaluation including discrimination, calibration, and preferably accuracies of predictions (e.g., AUC, calibration graphs, and the Brier score). 1. Include a motivation for the choice of measures, with references to existing literature where appropriate (e.g., Sokolova and Lapalme’s analysis of performance measures [108]). 2. Perform an error analysis and discuss the errors in the Discussion section of the paper. Include possible changes to the algorithm that could improve its performance for these specific errors. 3. When using a non-probabilistic NLP method: determine the cut-off value (a priori) for a ‘good’ test result before evaluating the algorithm. Elaborate why this cut-off value is chosen. |

Presentation of results

Authors report the evaluation results in various formats. Only twelve articles (16%) included a confusion matrix which helps the reader understand the results and their impact. Not including the true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives in the Results section of the publication, could lead to misinterpretation of the results of the publication’s readers. For example, a high F-score in an evaluation study does not directly mean that the algorithm performs well. There is also a possibility that out of 100 included cases in the study, there was only one true positive case, and 99 true negative cases, indicating that the author should have used a different dataset. Results should be clearly presented to the user, preferably in a table, as results only described in the text do not provide a proper overview of the evaluation outcomes (Table 11). This also helps the reader interpret results, as opposed to having to scan a free text paragraph. Most publications did not perform an error analysis, while this will help to understand the limitations of the algorithm and implies topics for future research.

Table 11.

Recommendation regarding the presentation of results

|

1. Report the outcomes of the evaluation in a clear manner, preferably in a table accompanied by a textual description of the outcomes. 1. Aim to include a confusion matrix in the reporting of the outcomes. 2. Use figures if they contribute to the making the results more readable and understandable for the reader. If a figure is used, make sure that the data is also available in the text or in a table. |

Generalizability of results

88% of the studies did not perform external validation (n = 68). Of the studies that claimed that their algorithm was generalizable, only 22% (n = 5) assessed this claim through external validation. However, one cannot claim generalizability without testing for it. Moreover, in 19% (n = 3) of the cases where external datasets were used, the datasets were not referenced and only listed in the text of the article, making it harder to find the used data and reproduce the results. Algorithm performance should be compared to that of other state-of-the-art algorithms, as this helps the reader decide whether the new algorithm could be considered useful for clinical practice. However, only 24 studies (31%) made this comparison, and four of those studies (17%) tested the performance difference for statistical significance. We also found that the authors’ descriptions of generalizability are rather ambiguous and unclear. We formulated five recommendations regarding the generalizability of results (Table 12).

Table 12.

Recommendation regarding the generalizability of results

|

1. Compare the results of the evaluated algorithm with other algorithms by using the same dataset as reported in the publication of the other algorithm or by processing the same dataset with another algorithm available through the literature. Report the outcomes of both experiments and test for statistical significance. 2. Describe in what setting the research is performed. Include if the research is part of a challenge (e.g., i2b2 challenge), or that the research is carried out in a specific institute or department. 3. Before claiming generalizability, perform external validation by testing the algorithm on a different, external dataset from other research projects or other publicly available datasets. Aim to use a dataset with a different case mix, different individuals, and different types of text. 4. Determine and describe if there are potential sources of bias in data selection, data use by the NLP algorithm or system, and evaluation. 5. When claiming generalizability, clearly describe the conditions under which the algorithm can be used in a different setting. Describe for which population, domain, and type and language of data the algorithm can be used. |

Strengths

Our study has three main strengths: First, to our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that focuses on the evaluation of NLP algorithms in medicine. Second, we used a large number of databases for our search, resulting in publications from many different sources, such as medical journals and computer science conferences. Third, we used existing statements and guidelines and harmonized them to induce our findings and used these findings to propose a list of recommendations.

Limitations

Several limitations of our study should be noted as well. First, we only focused on algorithms that evaluated the outcomes of the developed algorithms. Second, the majority of the studies found by our literature search used NLP methods that are not considered to be state of the art. We found that only a small part of the included studies was using state-of-the-art NLP methods, such as word and graph embeddings. This indicates that these methods are not broadly applied yet for algorithms that map clinical text to ontology concepts in medicine and that future research into these methods is needed. Lastly, we did not focus on the outcomes of the evaluation, nor did we exclude publications that were of low methodological quality. However, we feel that NLP publications are too heterogeneous to compare and that including all types of evaluations, including those of lesser quality, gives a good overview of the state of the art.

Conclusion

In this study, we found many heterogeneous approaches to the development and evaluation of NLP algorithms that map clinical text fragments to ontology concepts and the reporting of the evaluation results. Over one-fourth of the publications that report on the use of such NLP algorithms did not evaluate the developed or implemented algorithm. In addition, over one-fourth of the included studies did not perform a validation and nearly nine out of ten studies did not perform external validation. Of the studies that claimed that their algorithm was generalizable, only one-fifth tested this by external validation. Based on the assessment of the approaches and findings from the literature, we developed a list of sixteen recommendations for future studies. We believe that our recommendations, along with the use of a generic reporting standard, such as TRIPOD, STROBE, RECORD, or STARD, will increase the reproducibility and reusability of future studies and algorithms.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACL

Association for Computational Linguistics

- ACM

Association for Computing Machinery

- EHR

Electronic Health Record

- FN

False Negatives

- FP

False Positives

- HPO

Human Phenotype Ontology

- NLP

Natural Language Processing

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

- TN

True Negatives

- TP

True Positives

Authors’ contributions

Study conception and design: MK, RC, DA, and AA. Acquisition of data: FP and MK. Analysis and interpretation of data: FP and MK. Drafting of manuscript: MK. Critical revision: RC, DA, and AA. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Castor EDC and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during the study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Martijn G. Kersloot, Email: m.g.kersloot@amsterdamumc.nl

Florentien J. P. van Putten, Email: f.j.vanputten@amsterdamumc.nl

Ameen Abu-Hanna, Email: a.abu-hanna@amsterdamumc.nl.

Ronald Cornet, Email: r.cornet@amsterdamumc.nl.

Derk L. Arts, Email: d.l.arts@amsterdamumc.nl

References

- 1.Ford E, Nicholson A, Koeling R, Tate AR, Carroll J, Axelrod L, et al. Optimising the use of electronic health records to estimate the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in primary care: what information is hidden in free text? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Rosenbloom ST, Denny JC, Xu H, Lorenzi N, Stead WW, Johnson KB. Data from clinical notes: a perspective on the tension between structure and flexible documentation. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2011;18:181–186. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2010.007237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coorevits P, Sundgren M, Klein GO, Bahr A, Claerhout B, Daniel C, et al. Electronic health records: new opportunities for clinical research. J Intern Med. 2013;274:547–560. doi: 10.1111/joim.12119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danciu I, Cowan JD, Basford M, Wang X, Saip A, Osgood S, et al. Secondary use of clinical data: the Vanderbilt approach. J Biomed Inform. 2014;52:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Price SJ, Stapley SA, Shephard E, Barraclough K, Hamilton WT. Is omission of free text records a possible source of data loss and bias in clinical practice research Datalink studies? A case-control study. BMJ Open. 2016;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Gruber TR. A translation approach to portable ontology specifications. Knowl Acquis. 1993;5:199–220. doi: 10.1006/knac.1993.1008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.SNOMED International. SNOMED CT http://www.snomed.org/snomed-ct/five-step-briefing. Accessed 29 Jun 2020.

- 8.Köhler S, Carmody L, Vasilevsky N, Jacobsen JOB, Danis D, Gourdine JP, et al. Expansion of the human phenotype ontology (HPO) knowledge base and resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D1018–D1027. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krasowski M, Schriever A, Mathur G, Blau J, Stauffer S, Ford B. Use of a data warehouse at an academic medical center for clinical pathology quality improvement, education, and research. J Pathol Inform. 2015;6:45. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.161615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu H, Toti G, Morley KI, Ibrahim ZM, Folarin A, Jackson R, et al. SemEHR: a general-purpose semantic search system to surface semantic data from clinical notes for tailored care, trial recruitment, and clinical research. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 2018;25:530–537. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocx160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shivade C, Malewadkar P, Fosler-Lussier E, Lai AM. Comparison of UMLS terminologies to identify risk of heart disease using clinical notes. J Biomed Inform. 2015;58:S103–S110. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2015.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lingren T, Thaker V, Brady C, Namjou B, Kennebeck S, Bickel J, et al. Developing an algorithm to detect early childhood obesity in two tertiary pediatric medical centers. Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7(3):693–706. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2016-01-RA-0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ni Y, Kennebeck S, Dexheimer JW, McAneney CM, Tang H, Lingren T, et al. Automated clinical trial eligibility prescreening: increasing the efficiency of patient identification for clinical trials in the emergency department. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2015;22:166–178. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun H, Depraetere K, De Roo J, Mels G, De Vloed B, Twagirumukiza M, et al. Semantic processing of EHR data for clinical research. J Biomed Inform. 2015;58:247–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kreimeyer K, Foster M, Pandey A, Arya N, Halford G, Jones SF, et al. Natural language processing systems for capturing and standardizing unstructured clinical information: a systematic review. J Biomed Inf. 2017;73:14–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez-Hernandez G, Sarker A, O’Connor K, Savova G. Capturing the Patient’s perspective: a review of advances in natural language processing of health-related text. Yearb Med Inf. 2017;26:214–227. doi: 10.15265/IY-2017-029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jovanovic J, Bagheri E, Jovanović J, Bagheri E, Jovanovic J, Bagheri E, et al. Semantic annotation in biomedicine: the current landscape. J Biomed Semant. 2017;8:44. doi: 10.1186/s13326-017-0153-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.UK EQUATOR Centre. The EQUATOR Network. https://www.equator-network.org/. Accessed 29 Jun 2020.

- 19.Ford E, Carroll JA, Smith HE, Scott D, Cassell JA. Extracting information from the text of electronic medical records to improve case detection: a systematic review. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2016;23:1007–1015. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vuokko R, Makela-Bengs P, Hypponen H, Lindqvist M, Doupi P, Mäkelä-Bengs P, et al. Impacts of structuring the electronic health record: results of a systematic literature review from the perspective of secondary use of patient data. Int J Med Inform. 2017;97:293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KGM, TRIPOD Group Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. TRIPOD Group Circ. 2015;131:211–219. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, Harron K, Moher D, Peteresen I et al. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) Statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12:1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig L, et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ. 2015;351:h5527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Altman D, Antes G et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:1–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.The EndNote Team. EndNote. Philadelphia: Clarivate; 2013.

- 27.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne: Veritas Health Innovation; 2020.

- 29.Afshar M, Dligach D, Sharma B, Cai X, Boyda J, Birch S, et al. Development and application of a high throughput natural language processing architecture to convert all clinical documents in a clinical data warehouse into standardized medical vocabularies. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26:1364–1369. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocz068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alnazzawi N, Thompson P, Ananiadou S. Mapping Phenotypic Information in Heterogeneous Textual Sources to a Domain-Specific Terminological Resource. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0162287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atutxa A, Perez A, Casillas A. Machine Learning Approaches on Diagnostic Term Encoding with the ICD for Clinical Documentation. IEEE J Biomed Heal Informatics. 2018;22(4):1323–1329. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2017.2743824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrett N, Weber-Jahnke JH, Thai V. Engineering natural language processing solutions for structured information from clinical text: extracting sentinel events from palliative care consult letters. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;192:594–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Becker M, Bockmann B. Extraction of UMLS(R) Concepts Using Apache cTAKES for German Language. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2016;223:PG-71–PG-76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Becker M, Kasper S, Böckmann B, Jöckel K-H, Virchow I. Natural language processing of German clinical colorectal cancer notes for guideline-based treatment evaluation. Int J Med Inform. 2019;127:141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bejan CA, Wei WQ, Denny JC. Assessing the role of a medication-indication resource in the treatment relation extraction from clinical text. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2015;22:e162–e176. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castro E, Iglesias A, Martínez P, Castaño L. Automatic Identification of Biomedical Concepts in Spanish-language Unstructured Clinical Texts. German Research Cent for Artificial, Intelligence - DFKI GmbH, Kaiserslautern, Germany Seattle, WA, USA: ACM. 2010. pp. 751–757. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Catling F, Spithourakis GP, Riedel S. Towards automated clinical coding. Int J Med Inform. 2018;120:50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chapman WW, Fiszman M, Dowling JN, Chapman BE, Rindflesch TC. Identifying respiratory findings in emergency department reports for biosurveillance using MetaMap. Medinfo. 2004;11:487–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen J, Zheng J, Yu H. Finding Important Terms for Patients in Their Electronic Health Records: A Learning-to-Rank Approach Using Expert Annotations. JMIR Med informatics. 2016;4(4):e40. doi: 10.2196/medinform.6373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiaramello E, Pinciroli F, Bonalumi A, Caroli A, Tognola G. Use of “off-the-shelf” information extraction algorithms in clinical informatics: A feasibility study of MetaMap annotation of Italian medical notes. J Biomed Inform. 2016;63:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2016.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chodey KP, Hu G. 2016 IEEE/ACIS 15th International Conference on Computer and Information Science (ICIS) 2016. Clinical text analysis using machine learning methods; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chung J, Murphy S. Concept-value pair extraction from semi-structured clinical narrative: a case study using echocardiogram reports. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2005:131–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Combi C, Zorzi M, Pozzani G, Moretti U, Arzenton E. From narrative descriptions to MedDRA: automagically encoding adverse drug reactions. J Biomed Inform. 2018;84:184–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Bruijn B, Cherry C, Kiritchenko S, Martin J, Zhu X. Machine-learned solutions for three stages of clinical information extraction: The state of the art at i2b2 2010. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2011;18(5):557–562. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deisseroth CA, Birgmeier J, Bodle EE, Kohler JN, Matalon DR, Nazarenko Y, et al. ClinPhen extracts and prioritizes patient phenotypes directly from medical records to expedite genetic disease diagnosis. Genet Med. 2019;21:1585–1593. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0381-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Demner-Fushman D, Rogers WJ, Aronson AR. MetaMap Lite: An evaluation of a new Java implementation of MetaMap. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2017;24(4):841–844. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Divita G, Zeng QT, Gundlapalli AV, Duvall S, Nebeker J, Samore MH. Sophia: A Expedient UMLS Concept Extraction Annotator. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2014;2014:467–476. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duarte F, Martins B, Pinto CS, Silva MJ. Deep neural models for ICD-10 coding of death certificates and autopsy reports in free-text. J Biomed Inform. 2018;80:64–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2018.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Falis M, Pajak M, Lisowska A, Schrempf P, Deckers L, Mikhael S, et al. Ontological attention ensembles for capturing semantic concepts in ICD code prediction from clinical text. 2019. pp. 168–177. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferrão JC, Janela F, Oliveira MD, HMG M. 2013 IEEE International Conference on Healthcare Informatics. 2013. Using Structured EHR Data and SVM to Support ICD-9-CM Coding; pp. 511–516. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gerbier S, Yarovaya O, Gicquel Q, Millet A-L, Smaldore V, Pagliaroli V, et al. Evaluation of natural language processing from emergency department computerized medical records for intra-hospital syndromic surveillance. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2011;11:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Goicoechea Salazar JA, Nieto García MA, Laguna Téllez A, Canto Casasola VD, Rodríguez Herrera J, Murillo CF. Development of an automated coding system to retrieve and analyze diagnostic information stored in hospital emergency department records. Emergencias. 2013;25(6):430–436. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hamid H, Fodeh SJ, Lizama AG, Czlapinski R, Pugh MJ, LaFrance WC, Jr, et al. Validating a natural language processing tool to exclude psychogenic nonepileptic seizures in electronic medical record-based epilepsy research. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;29:578–580. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hassanzadeh H, Kholghi M, Nguyen A, Chu K. Clinical document classification using labeled and unlabeled data across hospitals. AMIA . Annu Symp proceedings AMIA Symp. 2018;2018:545–554. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Helwe C, Elbassuoni S, Geha M, Hitti E, Makhlouf OC. CCS Coding of Discharge Diagnoses via Deep Neural Networks. German Research Cent for Artificial, Intelligence - DFKI GmbH, Kaiserslautern, Germany Seattle, WA, USA: ACM. 2017. pp. 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hersh W, Mailhot M, Arnott-Smith C, Lowe H. Selective automated indexing of findings and diagnoses in radiology reports. J Biomed Inform. 2001;34(4):262–273. doi: 10.1006/jbin.2001.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoogendoorn M, Szolovits P, Moons LMG, Numans ME. Utilizing uncoded consultation notes from electronic medical records for predictive modeling of colorectal cancer. Artif Intell Med. 2015;69:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]