Abstract

Background

Gliomas are commonly diagnosed tumors in the central nervous system that have an elevated mortality rate. The present study evaluated pyrazolo[4,3-c]pyridine-4-one (PP-4-one) as an anti-proliferative agent against glioma cells and investigated the associated mechanism.

Material/Methods

The changes in cell growth were analyzed by Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) and apoptosis by flow cytometry using Annexin V-FITC staining kit. The FACSCalibur flow cytometer was used for analysis of DNA content and western blotting for protein expression.

Results

The PP-4-one treatment suppressed viability of U251, C6, and U87 cells significantly at a concentration of 0.25 μM. At a concentration of 16 μM, PP-4-one treatment for 72 hours suppressed viability of U251, C6, and U87 cells to 24%, 21%, and 20%, respectively. Treatment with PP-4-one suppressed cyclic 3′,5′-adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels in U251 and C6 cells significantly (P<0.05) depending on the concentration. The apoptotic cells were increased significantly (P<0.05) by PP-4-one treatment in U251 and C6 cell cultures. A considerable enhancement in the proportion of U251 and C6 cells in the G0/G1 phase was recorded on incubation with PP-4-one. Treatment of U251 and C6 cells with PP-4-one markedly enhanced p21 expression relative to the control. The B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2) level in PP-4-one treated U251 and C6 cells was markedly lower relative to the control cells. The Bax, caspase-3, and caspase-9 levels were elevated markedly by PP-4-one treatment in U251 and C6 cells.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that PP-4-one has anti-proliferative potential for glioma cells via targeting cAMP and Bcl-2 levels. It also promoted glioma cell apoptosis through caspase activation and arrest of the cell cycle. Thus, PP-4-one may be used to develop drug candidates for the glioma treatment.

MeSH Keywords: Apoptosis, Cell Cycle Checkpoints, Glioblastoma

Background

Gliomas are frequently diagnosed tumors in the central nervous system that have an elevated mortality rate and comprises 16% of all primary brain and central nervous system tumors [1]. Malignant gliomas are a commonly detected class of primary brain tumors which destroy neurons and are aggressive and highly invasive tumors with poor prognosis [2]. The genetic and cellular mechanism of gliomas has been investigated to a greater extent because of intensive efforts by clinicians [3]. The survival time for glioblastoma multiforme patients is only 2 years following diagnosis [4]. The progression from low-grade glioma to the high-grade glioma has different time durations depending in various patients [4]. Gliomas are presently treated by the use of radiotherapy/chemotherapy in combination with surgical resection [5]. In order to combat gliomas, it is important to understand its pathogenesis to help identify novel therapeutic targets [6]. The glioma treatment strategies currently used are not satisfactory and there is an urgent need for identification of effective therapeutic agent for glioma.

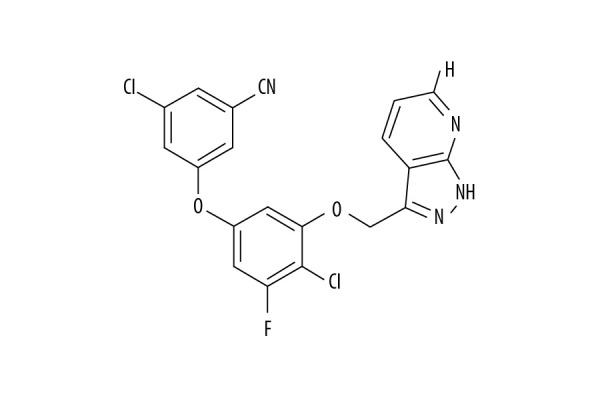

Pyrazole is one of the most important molecules in heterocyclic chemistry and many of its compounds are approved drugs [7]. Celecoxib and lonazolac are used as anti-inflammatory drugs, fipronil acts as an insecticide, dipyrone is a promising analgesic and antipyretic molecule [8], and sildenafil is used for erectile dysfunction treatment, all of these drugs are pyrazole based compounds [9]. Fused-pyrazoles have been found to exhibit several biological properties like anti-inflammatory [10], anti-viral [11], anti-tumor [12], anti-microbial [13], and antiprotozoal [14]. In addition, many fused-pyrazoles have shown significant anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) properties [15]. The anti-HIV activity of 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine-3-yl compounds is associated with inhibition of reverse transcriptase [15]. Another series of pyrazoles has been reported to exhibit anti-HIV property against both HIV-1 (IIIB) and HIV-2 (ROD) [15]. The present study evaluated pyrazolo[4,3-c]pyridine-4-one (PP-4-one) derivative (Figure 1) an anti-proliferative agent against glioma cells and investigated the associated mechanism.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of PP-4-one. Abbreviations: PP-4-one, pyrazolo[4,3-c]pyridine-4-one.

Pyrazole scaffold has been employed for synthesis of anticancer agents that explore multiple tumor targets [16]. The compound ABT-751 acts as tubulin inhibitor [17,18] while indenopyrazoles inhibit polymerization of the tubulin inhibitors [19]. Another pyrazole analog effectively inhibits viability of multidrug resistant tumor cells via targeting phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) activation and PTEN/Akt/NF-κB signaling [20].

Material and Methods

Reagents

1,5,6,7-tetrahydro-4H-pyrrolo[3,2-c]pyridin-4-one (CAS number PH003760) commonly known as pyrazolo[4,3-c]pyridine-4-one was obtained from Merck. All other chemicals were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich.

Cell line and culture

The U251, C6, and U87 cell lines were provided by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). The culture of cells was carried out at 37°C in RPMI-1640 medium which contained fetal bovine serum (10%) under 5% CO2 atmosphere. The antibiotics, penicillin (100 U/mL) and streptomycin (100 μg/mL) were also mixed with the medium.

Growth inhibition assay

The U251, C6, and U87 cells were distributed at 2×105 cells per well concentration in 96-well plates. The cell incubation for 24 hours was followed by treatment with 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 8.0, and 16 μM PP-4-one in RPMI-1640 medium. After 72 hours treatment, Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Laboratories, Japan) solution (10 μL) was put into the wells and incubation for an additional 1 hour was continued under same conditions. The cell viability measurements were made indirectly by recording optical density for each well using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, USA) 3 times at 456 nm wavelengths.

Determination of cyclic 3′,5′-adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) level

The U251 and C6 cells were distributed at 2×105 cells per well concentration in 24-well plates and treated with 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 8.0, and 16 μM PP-4-one for 72 hours. The phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) washing of cells and subsequent lysis with RIPA buffer for 40 minutes was followed by lysate centrifugation at 12 000 g for 15 minutes at 4°C to obtain supernatant. The supernatant was treated with hydrochloric acid (0.1 M) and DMEM/F12 for 30 minutes. The cAMP level in 30 μL sample of supernatant was analyzed on incubation with anti-cAMP primary antibodies at 4°C for 4 hours. Then samples were incubated with Northern Lights™ 557 conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G secondary antibodies.

Analysis of apoptosis

Apoptosis in U251 and C6 cells following treatment with PP-4-one was assessed using Annexin V-FITC staining kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). The cells distributed in 6-well plates at 2×106 cells per well concentration were treated with 2.0 and 16 μM PP-4-one or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, control) for 72 hours. Then cells were collected and subsequently treated with 200 μL of binding buffer solution. The cell suspension was treated with annexin V-FITC (10 μL) for 20 minutes under complete darkness at room temperature. Afterwards, cells were treated with binding buffer (300 μL) and propidium iodide (PI, 5 μL) prior to flow cytometric analysis using CELL Quest 3.0 software.

Cell cycle analysis

The U251 and C6 cells at 2×106 cells concentration were put into 10 cm culture dishes and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium for 24 hours. Then, cells were treated with 2.0 and 16 μM PP-4-one or DMSO (control) for 72 hours. The harvested cells were subjected to fixing in ethyl alcohol (70%) for 24 hours and then rinsed in PBS. Staining of the cells with PI solution (5%) was carried out in accordance with instructions from manufacturer. The FACSCalibur flow cytometer along with the Cell Quest software Pro (5.1 version; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) were employed for cell cycle analysis.

Western blot assay

The U251 and C6 cells after treatment with 2.0 and 16 μM PP-4-one or DMSO (control) for 72 hours were lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer. The lysate centrifugation at 12 000 g for 40 minutes at 4oC to obtain supernatant was followed bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay for measurement of protein concentration. The equal protein samples (30 μg) were subjected to electrophoresis on sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel and then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. Blocking of membranes was performed by incubation with 5% non-fat milk in tris-buffered saline and Tween (TBST). Incubation of the blots was carried out with primary antibodies at 4°C for overnight. The PBS washed blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies at room temperature for 2 hours. The immunoblots were subjected to visualization using electrochemiluminescent (ECL) assays along with the western blot detection system (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The primary antibodies used for membrane incubation were: anti-p21 (dilution 1: 500; Santa Cruz), anti-Bcl-2 (dilution 1: 500; Santa Cruz), anti-cleaved caspase-9 (dilution 1: 1000; Cell Signaling) and anti-cleaved caspase-3 (dilution 1: 1000; Cell Signaling).

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean±standard deviations of 3 independent experiments. The statistical analyses were carried out using Origin Lab software version 8.0 (Origin Lab, Northampton, MA, USA). The differences were analyzed statistically using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni post-test. The values were taken statistically significant at P<0.05.

Results

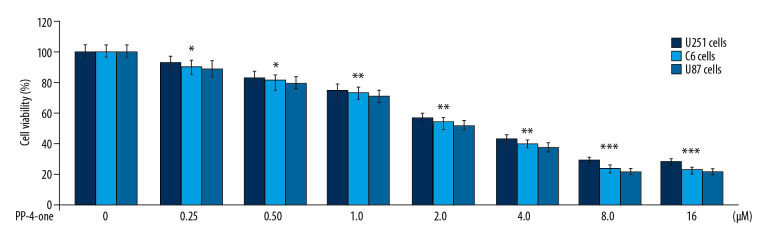

PP-4-one inhibited U251, C6, and U87 cell growth

The U251, C6, and U87 cells were growing at a significantly (P<0.05) higher rate in control cultures in comparison to PP-4-one treated cells (Figure 2). A gradual suppression in U251, C6, and U87 cell viability was caused by an increase in concentration from 0.25 to 16 μM. The PP-4-one treatment suppressed viability of U251, C6, and U87 cells significantly from 0.25 μM; at 16 μM, PP-4-one treatments for 72 hours suppressed viability of U251, C6, and U87 cells to 24%, 21%, and 20%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Effect of PP-4-one on U251, C6, and U87 cell viability. The PP-4-one was added to cells at 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 8.0, and 16 μM doses and viability was assessed at 72 hours. The changes in viability by PP-4-one were measured using CCK-8 assay * P<0.05, ** P<0.02, and *** P<0.01 versus control cells. PP-4-one – pyrazolo[4,3-c]pyridine-4-one; CCK-8 – Cell Counting Kit-8.

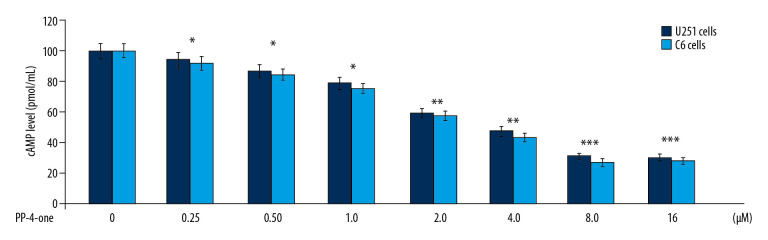

PP-4-one suppressed cAMP levels in U251 and C6 cells

The cAMP levels in U251 and C6 control cultures was much higher relative to those in the PP-4-one treated cultures at 72 hours (Figure 3). Treatment with PP-4-one suppressed cAMP levels in U251 and C6 cells significantly (P<0.05) depending on the concentration. The cAMP level was significantly (P<0.05) suppressed by PP-4-one from 0.25 μM. The reduction of cAMP level by PP-4-one was maximum at 16 μM.

Figure 3.

Inhibitory effect of PP-4-one on cAMP in U251 and C6 cells. The incubation with PP-4-one (0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 8.0, and 16 μM) for 72 hours was followed by assessment of cAMP levels in U251 and C6 cells. * P<0.05, ** P<0.02, and *** P<0.01 versus control cells. PP-4-one – pyrazolo[4,3-c]pyridine-4-one; cAMP – cyclic 3′,5′-adenosine monophosphate.

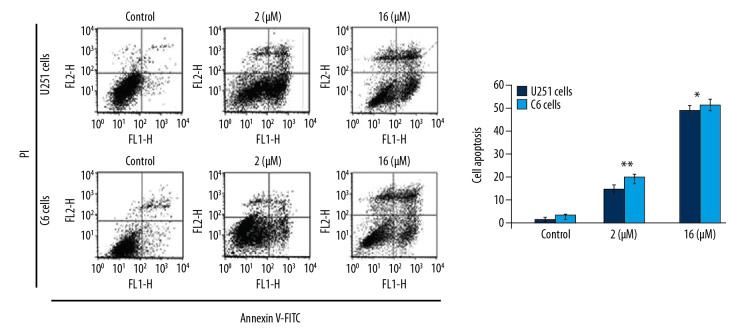

PP-4-one induced apoptosis in U251 and C6 cells

To assess apoptosis induction, we added PP-4-one at 1 μM and 16 μM concentrations to U251 and C6 cell cultures (Figure 4). The apoptotic cell count was increased significantly (P<0.05) by PP-4-one treatment in U251 and C6 cell cultures. Treatment with 1 μM PP-4-one increased apoptotic cell count to 15.43% and 19.87% in U251 and C6 cells, respectively. On increasing PP-4-one concentration to 16 μM, the apoptosis in U251 and C6 cells was enhanced to 48.65% and 53.21%, respectively.

Figure 4.

Apoptosis inducing effect of PP-4-one in U251 and C6 cells. The incubation with PP-4-one (1.0 μM and 16 μM) or DMSO for 72 hours was followed by flow cytometry to analyze apoptosis in U251 and C6 cells. * P<0.05 and ** P<0.02 versus control cells. PP-4-one – pyrazolo[4,3-c]pyridine-4-one; DMSO – dimethyl sulfoxide.

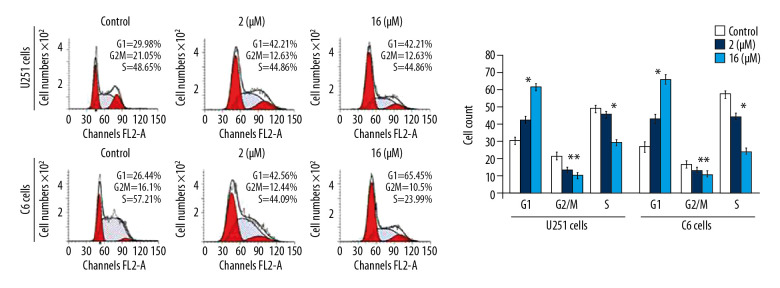

G0/G1 phase arrest of U251 and C6 cell cycle by PP-4-one

The PP-4-one treatment reduced U251 and C6 cell distribution in the G2/M phase significantly (P<0.05) at 72 hours (Figure 5). The U251 and C6 cell distribution was also decreased in the S phase significantly (P<0.05) on treatment with pyrazolo[4,3-c]pyridine-4-one. However, a considerable enhancement in the proportion of U251 and C6 cells in the G0/G1 phase was recorded on incubation with pyrazolo[4,3-c]pyridine-4-one. The enhancement of U251 and C6 cell counts in the G0/G1 phase was significant by the addition of PP-4-one both at 1 μM and 16 μM relative to control cells.

Figure 5.

Effect of PP-4-one on the cell cycle in U251 and C6 cells. The cells treated with PP-4-one (1.0 μM and 16 μM) or DMSO for 72 hours were analyzed using flow cytometry. * P<0.05 and ** P<0.02 versus control cells. PP-4-one – pyrazolo[4,3-c]pyridine-4-one; DMSO – dimethyl sulfoxide.

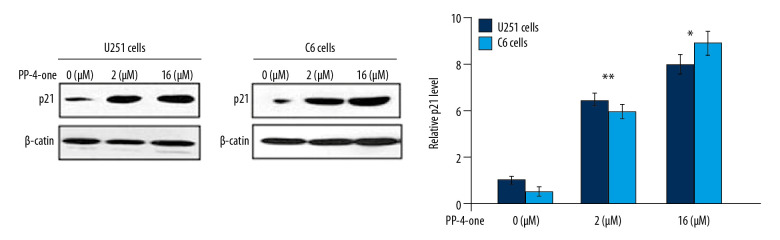

PP-4-one promoted p21 expression in U251 and C6 cells

The alteration in p21 expression by PP-4-one in U251 and C6 cells was assessed using western blot (Figure 6). Treatment of U251 and C6 cells with PP-4-one markedly enhanced p21 expression relative to the control. There was marked elevation of p21 levels in U251 and C6 cells on treatment with 1.0 μM and 16 μM pyrazolo[4,3-c]pyridine-4-one.

Figure 6.

Effects of PP-4-one on the cell cycle progression. The U251 and C6 cells after 72 hours treatment with PP-4-one (1.0 μM and 16 μM) or DMSO were assessed for p21 levels by western blotting and the data were quantitative analyzed. * P<0.05 and ** P<0.02 versus control cells. PP-4-one – pyrazolo[4,3-c]pyridine-4-one.

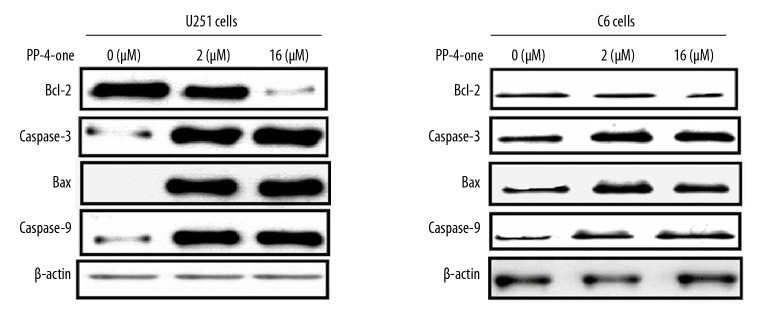

PP-4-one influenced apoptotic protein levels in U251 and C6 cells

In U251 and C6 cells alteration in Bcl-2, caspase-9, caspase-3 (cleaved) and Bax levels were detected at 72 hours of PP-4-one treatment by western blotting (Figure 7). The Bcl-2 level in PP-4-one treated U251 and C6 cells was markedly lower relative to the control cells. The Bax, caspase-3 and caspase-9 levels were elevated markedly by PP-4-one treatment in U251 and C6 cells. Elevation in Bax, caspase-3 and caspase-9 levels and suppression of Bcl-2 level was evident in U251 and C6 cells on treatment with 1.0 μM and 16 μM PP-4-one.

Figure 7.

Effect of by PP-4-one on apoptotic proteins. The U251 and C6 cells treated with PP-4-one (1.0 μM and 16 μM) or DMSO were assessed for Bcl-2, caspase-9, caspase-3 (cleaved) and Bax levels by western blotting. PP-4-one – pyrazolo[4,3-c]pyridine-4-one; DMSO – dimethyl sulfoxide.

Discussion

Glioblastoma multiforme treatment using an effective and successful therapeutic strategy is a serious challenge to clinicians worldwide and needs to be addressed as soon as possible. Towards this motive, several molecules have been discovered which possess inhibitory effect against various glioma cells [21]. The derivatives of pyrazole have been shown to be very effective anti-proliferative property in vivo and have antitumor activities in vivo in animal models. The present study showed growth inhibitory potential of PP-4-one against U251, C6, and U87 cells in a dose depending manner. The viability assay data provided evidence for anti-glioma potential of PP-4-one. There have been reports that activation of platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFRs) promotes cAMP levels [22,23]. In cell mitochondria, ATP is cleaved to produce cAMP under the influence of various cellular factors including PDGFRs [24,25]. The activation of PDGFs has been found to be linked with increased glioma cell growth and proliferation [24,25]. The cAMP level, and thereby glioma cell proliferation, has also been shown to be enhanced by β-adrenoreceptors [17,18]. The cAMP acts as messenger and plays a crucial role in various physiological as well as pathological settings [26]. The G-protein coupled receptors on stimulation by adenylyl cyclases produce cAMP as signal transducers. It has been reported that increased cAMP levels in lymphoid cells by anti-cancer agents can cause cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase and inhibit apoptosis [27–30]. It has been demonstrated in lymphoblastic leukemia cells that cAMP inhibits apoptosis in p53-dependent manner, and it antagonizes DNA damage [31,32]. In the present study PP-4-one considerably suppressed cAMP levels in U251, C6, and U87 cells. This suggests that PP-4-one suppresses U251, C6, and U87 cell viability by inhibiting cAMP activation. The glioma cell growth is generally suppressed by chemotherapeutics via targeting the Bcl-2 (anti-apoptotic protein) and promotion of caspase-9/caspase-3 levels [33,34]. The Bcl-2 suppression and caspase-9/caspase-3 promotion is also used as strategy in other types of cancer as well [35,36]. In the present study, PP-4-one treatment of U251 and C6 cells markedly reduced Bcl-2 protein level. Moreover, the Bax, caspase-9/caspase-3 levels were enhanced by PP-4-one treatment in U251 and C6 cells. In U251 and C6 cells PP-4-one treatment upregulated the onset of apoptosis. The apoptotic portion of U251 and C6 cells showed marked elevation in PP-4-one treated cultures relative to the control. In addition, treatment with PP-4-one markedly accumulated U251 and C6 cells in the G1/G0 phase of the cell cycle. The PP-4-one treated cultures showed relatively lower proportion of U251 and C6 cells in the G2/M and S phases. Therefore, anti-proliferative potential of PP-4-one involves changes of apoptotic protein expression in glioma cells. Apoptosis activation is associated with membrane permeability of mitochondria which allows release of cytochrome c and finally activates caspases [37]. In the present study, elevated levels of caspase-3/caspase-9 in PP-4-one treated cells suggested involvement of mitochondrial pathway.

Conclusions

The present study was the first to demonstrate anti-proliferative potential of PP-4-one for glioma cells via targeting cAMP and Bcl-2 levels. Moreover, PP-4-one promoted apoptosis via caspase activation and arrest of the cell cycle. Therefore, PP-4-one might be used to develop drug candidates for the glioma treatment.

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maher EA, Furnari FB, Bachoo RM, et al. Malignant glioma: Genetics and biology of a grave matter. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1311–33. doi: 10.1101/gad.891601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunn GP, Rinne ML, Wykosky J, et al. Emerging insights into the molecular and cellular basis of glioblastoma. Genes Dev. 2012;26:756–84. doi: 10.1101/gad.187922.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang SM, Lamborn KR, Malec M, et al. Phase II study of temozolomide and thalidomide with radiation therapy for newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60:353–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huse JT, Holland EC. Targeting brain cancer: Advances in the molecular pathology of malignant glioma and medulloblastoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:319–31. doi: 10.1038/nrc2818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh P, Bodiwala HS. Recent advances in anti-HIV natural products. Nat Prod Rep. 2010;27:1781–800. doi: 10.1039/c0np00025f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wasil M, Harris M, Henderson B. Antioxidant activity of dipyrone: Relationship to its anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity. Pharmacol Commun. 1992;1:337–44. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terrett NK, Bell AS, Brown D, Ellis P. Sildenafil (VIAGRATM), a potent and selective inhibitor of type 5 cGMP phosphodiesterase with utility for the treatment of male erectile dysfunction. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1996;6:1819–24. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tageldin GN, Fahmy SM, Ashour HM, et al. Design, synthesis and evaluation of some pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidines as anti-inflammatory agents. Bioorg Chem. 2018;78:358–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xing Y, Zuo J, Krogstad P, Jung ME. Synthesis and structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies of novel pyrazolopyridine derivatives as inhibitors of enterovirus replication. J Med Chem. 2018;61:1688–703. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nassar IF, El Farargy AF, Abdelrazek FM. Synthesis and anticancer activity of some new fused pyrazoles and their glycoside derivatives. J Heterocyclic Chem. 2018;55:1709–19. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdel Reheim MAM, Baker SM. Synthesis, characterization and in vitro antimicrobial activity of novel fused pyrazolo[3,4-c]pyridazine, pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine, thieno[3,2-c]pyrazole and pyrazolo[3′,4′: 4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives. Chem Cent J. 2017;11:112. doi: 10.1186/s13065-017-0339-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anand D, Yadav PK, Patel OP, et al. Antileishmanial activity of pyrazolopyridine derivatives and their potential as an adjunct therapy with miltefosine. J Med Chem. 2017;60:1041–59. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savant MM, Ladva KD, Pandit AB. Facile synthesis of highly functionalized novel pyrazolopyridones using oxoketene dithioacetal and their anti-HIV activity. Synth Commun. 2018;48:1640–48. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karrouchi K, Radi S, Ramli Y, et al. Synthesis and pharmacological activities of pyrazole derivatives: A review. Molecules. 2018;23:134. doi: 10.3390/molecules23010134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee H-Y, Pan S-L, Su M-C, et al. Furanylazaindoles: Potent anticancer agents in vitro and in vivo. J Med Chem. 2013;56:8008–18. doi: 10.1021/jm4011115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen NE, Maldonado NV, Khankaldyyan V, et al. Reactive oxygen species mediates the synergistic activity of fenretinide combined with the microtubule inhibitor ABT-751 against multidrug-resistant recurrent neuroblastoma xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:2653–64. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu YN, Wang JJ, Ji YT, et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of 1-methyl-1,4-dihydroindeno[1,2-c]pyrazole analogues as potential anticancer agents targeting tubulin colchicine binding site. J Med Chem. 2016;59:5341–35. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, Gong F-L, Lu Z-N, et al. DHPAC, a novel synthetic microtubule destabilizing agent, possess high anti-tumor activity in vincristine-resistant oral epidermoid carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2017;93:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uziel O, Fenig E, Nordenberg J, et al. Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) downregulates telomerase activity and inhibits proliferation in telomerase-expressing cell lines. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1881–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sokołowska P, Nowak JZ. Constitutive activity of beta-adrenergic receptors in C6 glioma cells. Pharmacol Rep. 2005;57:659–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grobben B, De Deyn PP, Slegers H. Rat C6 glioma as experimental model system for the study of glioblastoma growth and invasion. Cell Tissue Res. 2002;310:257–70. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0651-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaiswal BS, Conti M. Calcium regulation of the soluble adenylyl cyclase expressed in mammalian spermatozoa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10676–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1831008100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baillie GS, Houslay MD. Arresting times for compartmentalized cAMP signalling and phosphodiesterase-4 enzymes. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:129–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torgersen KM, Vang T, Abrahamsen H, et al. Molecular mechanisms for protein kinase A-mediated modulation of immune function. Cell Signal. 2002;14:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blomhoff HK, Blomhoff R, Stokke T, et al. cAMP-mediated growth inhibition of a B-lymphoid precursor cell line Reh is associated with an early transient delay in G2/M, followed by an accumulation of cells in G1. J Cell Physiol. 1988;137:583–87. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041370327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blomhoff HK, Smeland EB, Beiske K, et al. Cyclic AMP-mediated suppression of normal and neoplastic B cell proliferation is associated with regulation of myc and Ha-ras protooncogenes. J Cell Physiol. 1987;131:426–33. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041310315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naderi S, Gutzkow KB, Christoffersen J, et al. cAMP-mediated growth inhibition of lymphoid cells in G1: Rapid down-regulation of cyclin D3 at the level of translation. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1757–68. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200006)30:6<1757::AID-IMMU1757>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naderi S, Wang JY, Chen TT, et al. cAMP-mediated inhibition of DNA replication and S phase progression: Involvement of Rb, p21Cip1, and PCNA. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1527–42. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-06-0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naderi EH, Findley HW, Ruud E, et al. Activation of cAMP signaling inhibits DNA damage-induced apoptosis in BCP-ALL cells through abrogation of p53 accumulation. Blood. 2009;114:608–18. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-204883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naderi EH, Jochemsen AG, Blomhoff HK, Naderi S. Activation of cAMP signaling interferes with stress-induced p53 accumulation in ALL-derived cells by promoting the interaction between p53 and HDM2. Neoplasia. 2011;13:653–63. doi: 10.1593/neo.11542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malla R, Gopinath S, Alapati K, et al. Downregulation of uPAR and cathepsin B induces apoptosis via regulation of Bcl-2 and Bax and inhibition of the PI3K/AKT pathway in gliomas. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 34.Das A, Banik NL, Ray SK. Flavonoids activated caspases for apoptosis in human glioblastoma T98G and U87MG cells but not in human normal astrocytes. Cancer. 2010;116:164–76. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang F, Chen Y, Duan W, et al. SH-7, a new synthesized Shikonin derivative, exerting its potent antitumor activities as a topoisomerase inhibitor. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1184–93. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tomicic MT, Christmann M, Kaina B. Topotecan triggers apoptosis in p53-deficient cells by forcing degradation of XIAP and survivin thereby activating caspase-3-mediated Bid cleavage. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;332:316–25. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.159962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Antonsson B, Martinou JC. The Bcl-2 protein family. Exp Cell Res. 2000;256:50–57. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]