Abstract

Objective:

To investigate age-related trends in physically aggressive behaviors prior to the age of 2 years. With exceptions (eg, hair pulling), we hypothesized age-related increases in both prevalence and frequency of aggressive behaviors.

Study design:

A normative US sample of 477 mothers of 6- to 24-month-old children reported on the frequency of nine interpersonally directed aggressive child behaviors in the past month.

Results:

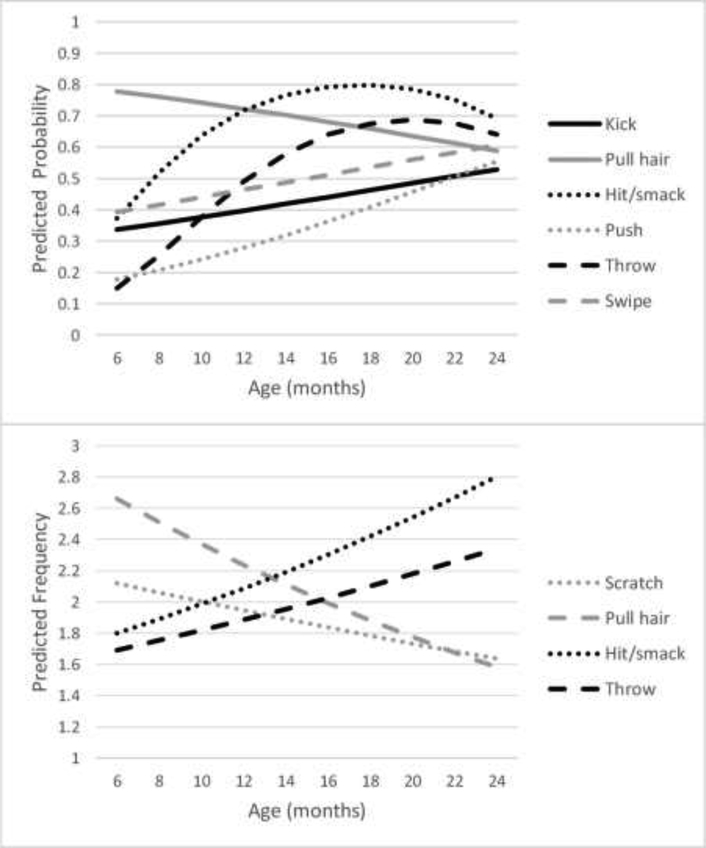

94% of children were reported to have engaged in physically aggressive behavior in the past month. Based on two-part regression models, the prevalences of kicking (OR = 1.70; P = .023), pushing (OR = 3.22; P < .001), and swiping (OR = 1.78; P = .018) each increased with age. The prevalence of hair pulling decreased (OR = 0.55; P = .020) with age. The prevalences of hitting and throwing initially increased, but plateaued at 18–20 months of age before decreasing (quadratic ORa = 0.13 and 0.16, P < .001 and .010, respectively). The frequencies of hitting (R2 = .05; P < .001) and throwing (R2 = .03; P = .030) increased, and the frequencies of hair pulling (R2 = .07; P < .001) and scratching (R2 = .02; P = .042) decreased with age. These P values are false discovery rate-adjusted.

Conclusions:

Physically aggressive behavior in the 6- to 24-month age range appears to be nearly ubiquitous. Most, but not all, forms of physical aggression increase with age. These results can guide pediatricians as they educate and counsel parents about their child’s behavior in the first 2 years of life.

Keywords: Aggression, Child Behavior, Child Development, Infancy, Toddlerhood

Although there is much research on physical aggression in children beginning at age 2 years,1–3 knowledge of the development of physically aggressive behavior in younger children is limited and lacks consistency.4–7 . Childhood aggression is a risk factor for violence later in life; a pattern of abnormally elevated PA that lasts for years is in place for 3% to 18% of children by 24 months.1–3 Moreover, the stability of PA prior to age two years suggests the possibility that persistently elevated PA may be established at an even younger age.4,7,8

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that healthcare providers routinely screen for behavior problems during well child visits and educate parents about appropriate discipline strategies as indicated.9 Because it is common, early childhood PA may in part be responsible for parents’ desires for counseling on disciplinary strategies in this age range, identified as a frequent unmet need in well-child visits.10,11 Clinicians, faced with parent reports of child PA, require an empirical frame of reference to judge whether a given behavior is age-appropriate or age-deviant, necessitating intervention.

Although many physically aggressive behaviors increase prior to the age of 2 years –12 – others show little change or may in fact decrease. We found, in a moderately at-risk United States (US) sample, that the prevalence of PA increased from age 8 months to 24 months for pushing (13% to 49%), hitting (39% to 67%) and kicking (22% to 31%).7 In contrast, the prevalence of biting increased between 8 (30%) and 15 (46%) months, but decreased to 32% by 24 months. From 8 to 24 months, the prevalences of hair pulling (73% to 31%) and combined pinching/scratching (44% to 32%) decreased with age. Additionally, a normative study of Norwegian children found that, by 24 months, different types of PA had increased (e.g., pushing and kicking) or plateaued (e.g., hitting) and other types of PA had decreased (e.g., biting).6

The aim of the present study is to replicate and extend prior findings with detailed examination of normative age-related trends in individual physically aggressive behaviors prior to the age of 2 years. We measured both the prevalence and frequency of 10 PA behaviors between 6 and 24 months of child age. The prevalence and frequency of PA behaviors can potentially have differing associations with age. For example, hitting can become more frequent with age among those children who hit others without the percentage of children who hit increasing with age. As an additional design consideration, we assessed behavior frequency with sufficient specificity to yield practically interpretable findings (i.e., the approximate number of days per week a given behavior is exhibited). Finally, to enhance the generalizability of our findings, we recruited a sample that was demographically similar to the US population.

Prevailing developmental forces may make PA increasingly likely between 6 and 24 months: normative increases in anger,13 locomotion,14 the ability to recognize conflicts of one’s own vs. others’ goal-directed behaviors,15 conflict with caregivers,16 as well as muscle strength and motor coordination.17 Thus, increases in both prevalence and frequency of most PA behaviors are our default prediction. However, we tempered these predictions with the available evidence: decreases in hair pulling and combined pinching/scratching7, as well as curvilinear trends in hitting, kicking, and biting.6,7

Method

The study protocol was approved by the New York University Committee on Activities Involving Human Subjects. It was carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). Study parents were members of the proprietary panel of Qualtrics, a marketing research firm. The panel comprises research participants recruited from several sources (e.g., social media and web publishers). To qualify for the present study (N = 528), the respondent needed to be an adult mother of a 6- to 24-month-old child residing in the continental US who was comfortable completing the survey in English. Each parent also needed to successfully pass a quality control measure to be included in the present analyses: correctly responding to a validation item embedded in the child behavior questionnaire (“We just want to see if you’re still awake. Please select ‘Many times each day.’”). This procedure eliminated the 9.7% of qualifying parents who were insufficiently attentive to provide accurate answers, yielding the final sample size of 477.

Several recruitment quotas were established to ensure an even representation of children across the 6- to 24-mo age spectrum and net a sample reasonably representative of the US population. Child age quotas: 16.7 +/− 5.0% in each 3-mo band from 6 to 20 months and in the 4-mo 21- to 24-mo band. Child ethnicity and race quotas: Hispanic/Latino of any race (17.1 +/− 7.5%), and non-Hispanic/Latino white alone (62.3 +/− 10.0%), black alone (12.3 +/− 5.0%), and all other racial categories (8.3 +/− 5.0%). Parent quotas: bachelor’s degree or higher (29.8 +/− 10.0%) and family income below $66,000 (29.8 +/− 10.0%). Recruitment proceeded until each quota was filled. Other than child age, quota targets were based on US Census data.18

Child age ( = 14.72, SD = 5.25 months) was roughly equally distributed in the six age bands; goodness of fit χ2 (5) = 1.33, P = .932. Children were 47.8% female and 18.3% were Hispanic/Latino of any race. Among non-Hispanic/Latino children, 4.2% were Asian, 13.1% were black, 60.2% were white, 3.8% were mixed race, and 0.4% were another race. Mothers were 18 to 54 years old ( = 29.95, SD = 6.16) and 18.5% were Hispanic/Latino of any race. Among non-Hispanic/Latino mothers, 4.8% were Asian, 13.4% were black, 59.2% were white, 2.9% were mixed race, and 1.1% were another race. Most mothers (90.8%) were either married or lived with a partner; 29.1% had earned a bachelor’s degree or better; 50.3% were employed. Annual family income was assessed in ranges: ≤ $25,000 (15.6%), $26,000 - $45,000 (24.7%), $46,000 - $65,000 (15.4%), $66,000 - $85,000 (19.4%), $86,000 - $105,000 (14.1%), and ≥$106,000 (10.8%). Child age, the explanatory variable, was not significantly associated with other demographic variables.

Parents completed on-line questionnaires that included screening and demographic questions, the Child Behavior Record, and other measures not of present focus. Data collection occurred in June, 2017.

Measures

The PA subscale of the Child Behavior Record (CBR; on-line only) is the present focus. The CBR is a new measure in which the parent is asked to indicate the weekly frequency of each of 18 child behaviors in the last month. The CBR incorporates all seven PA behaviors of the Infant Externalizing Questionnaire, which was designed for developmental relevance to infancy and toddlerhood and exhibited multiple indications of reliability and validity in a prior study.19 The CBR adds items measuring additional PA acts identified by Hay et al.20

The CBR’s PA subscale consists of 10 items: (1) “kick someone,” (2) “scratch someone,” (3) “ pull someone’s hair,” (4) “hit or smack someone (with hand or object)” (5) “ pinch someone,” (6) “hurt animals (for example, hit ir/ r lling, s r t hing, hitting, in hing)”, (7) “ ite so eone (not in l ing n rsing, n even i s/he oes not h ve teeth yet)”, (8) “ sh or shove so eone,” (9) “throw n o je t t so eone,” n (10) “swi e t so eone without making ont t.” The CBR uses response scale of the Multidimensional Assessment of Preschool Disruptive Behavior:21 0 = Never, 1 = Rarely (less than once a week), 2 = Some (1–3) days of the week, 3 = Most (4–6) days of the week, 4 = Every day of the week, and 5 = Many times each day.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted using Mplus version 8.0,22 using robust full information maximum likelihood estimation to handle missingness (2 parents skipped 1 CBR item each), keeping the analysis N at a constant 477. Two-part regression models 23 were used to test the relation of PA behaviors with child age. These models treated the PA ite s’ istri tions as semicontinuous, with a proportion of responses equal to 0 (no PA) and a continuous distribution among the remaining responses, ranging from 1 to 5 (at least some PA). Two-part regression analyses express the relation of a criterion variable (e.g., PA) and predictors (e.g., age) in a simultaneously estimated pair of regression models, a logistic regression model for the binary (behavior present vs. absent) and a linear regression model for the continuous (level among nonzero cases) portions of the distribution. To test linear age-PA associations, binary (values of 1 and 0) and natural log transformed non-zero continuous (values from 1 to 5) variables for the 10 PA behaviors were simultaneously regressed on age. To test curvilinear age-PA associations, squared and cubed age terms were added in separate models. In all regression models, age was rescaled from months to years to avoid large variances of nonlinear age variables. Residual covariances were allowed among the continuous variables.

To control Type-1 error, the false discovery rate (FDR) adjustment 24 was applied separately to the P values of the 10 binary and 10 continuous hypothesized age-PA associations in the linear, quadratic, and cubic effects models.

Effect size is reported in the odds ratio metric for binary variables (change in odds of PA behavior present vs. absent with each increasing year in age) and the R2 metric for continuous variables (proportion of variance in PA, if non-zero, that is explained by age). In tests of quadratic effects, effect size is reported as R2 increment (ΔR2) uniquely attritubtable to squared age.

Results

Nearly all (94.32%) of the children were reported to have engaged in at least one act of PA in the past month; = 0.98 and SD = 0.79 among the non-zero responses. Behavior-level descriptive statistics, in the variables’ origin l s ling, are reported in Table I.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Aggressive Behaviors

| Frequency |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | SD | Minimum | Maximum | ||

| Kick someone | 42.9% | 1.80 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Scratch someone | 55.6% | 1.88 | 1.18 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Pull someone’s hair | 69.2% | 2.11 | 1.23 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Hit or smack someone | 69.6% | 2.28 | 1.37 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Pinch someone | 35.4% | 1.95 | 1.29 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Hurt animals | 26.4% | 1.67 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Bite someone | 44.4% | 1.65 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Push or shove someone | 34.4% | 1.72 | 1.11 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Throw an object at someone | 52.3% | 2.05 | 1.26 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Swipe at someone without making contact | 49.7% | 1.89 | 1.17 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

Prevalence based on behavior present in the past month; frequency , SD, minimum, and maximum based on non-zero values only; frequency response choices are 0 (Never), 1 (Rarely [less than once a week]), 2 (Some [1–3] days of the week), 3 (Most [4–6] days of the week), 4 (Every day of the week), and 5 (Many times each day).

In Model 1 (linear), the binary and continuous representations of each PA behavior were regressed on age in years (Table 2). After the FDR correction was applied, seven behaviors were significantly associated with age. Among binary variables, the probability of kicking, hitting, pushing, throwing, and swiping each increased as a linear function of age; hair pulling was less prevalent in older children. Among continuous variables, and restricted to non-zero values, hitting and throwing were positively associated with age; scratching and hair pulling were negatively associated with age.

Table 2.

Linear Association of Age and Aggressive Behaviors (Model 1)

| Behavior Present/Absent |

Behavior Frequency† |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion/Predictor | b | SE | P | PFDR | CI low | CI high | OR | b | SE | P | PFDR | CI low | CI high | R2 |

| Kick Age | 0.53 | 0.22 | .014 | .023 | 0.11 | 0.95 | 1.70 | −0.71 | 0.08 | .033 | .066 | −0.33 | −0.01 | .02 |

| Scratch Age | 0.22 | 0.21 | .30 | .30 | −0.64 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.17 | 0.07 | .017 | .042 | −0.31 | −0.03 | .02 |

| Pull hair Age | −0.60 | 0.23 | .010 | .020 | −1.06 | −0.14 | 0.55 | −0.35 | 0.07 | <.001 | <.001 | −0.48 | −0.22 | .07 |

| Hit or smack Age | 1.02 | 0.26 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.51 | 1.53 | 2.77 | 0.30 | 0.08 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.15 | 0.44 | .05 |

| Pinch Age | 0.31 | 0.22 | .153 | .177 | −0.12 | 0.74 | 1.37 | 0.03 | 0.10 | .781 | .781 | −0.22 | 0.16 | .00 |

| Hurt animals Age | 0.32 | 0.22 | .159 | .177 | −0.12 | 0.76 | 1.37 | 0.08 | 0.10 | .381 | .544 | −0.10 | 0.27 | .01 |

| Bite Age | 0.44 | 0.21 | .035 | .050 | 0.03 | 0.85 | 1.55 | 0.04 | 0.07 | .594 | .742 | −0.11 | 0.18 | .00 |

| Push Age | 1.17 | 0.23 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.72 | 1.62 | 3.22 | 0.03 | 0.09 | .732 | .781 | −0.14 | 0.20 | .00 |

| Throw Age | 1.56 | 0.24 | <.001 | <.001 | 1.08 | 2.04 | 4.76 | 0.22 | 0.08 | .009 | .030 | 0.05 | 0.38 | .03 |

| Swipe Age | 0.58 | 0.21 | .007 | .018 | 0.16 | 0.99 | 1.78 | 0.07 | 0.08 | .347 | .544 | −0.08 | 0.23 | .00 |

Age scaled as years;

means restricted to non-zero cases.

In Model 2 (quadratic), the binary and continuous PA variables were regressed on age and age2 (Table 3). Two behaviors (binary) exhibited significant curvilinear associations with age: hitting and throwing. For these two behaviors, the positive age-PA association plateaued and began to become negative with increasing age.

Table 3.

Curvilinear Association of Age and Aggressive Behaviors (Model 2)

| Behavior Present/Absent |

Behavior Frequency† |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion/Predictor | b | SE | P | PFDR | CI Low | CI High | ORa | b | SE | P | PFDR | CI low | CI high | ΔR2 |

| Kick | ||||||||||||||

| Age | 0.24 | 1.32 | .859 | −2.35 | 2.82 | −0.09 | 0.52 | .863 | −1.11 | 0.93 | ||||

| Age2 | 0.12 | 0.52 | .820 | .941 | −0.91 | 1.14 | −0.03 | 0.20 | .869 | .970 | −0.43 | 0.36 | .00 | |

| Scratch | ||||||||||||||

| Age | 1.42 | 1.29 | .271 | −1.11 | 3.95 | −0.19 | 0.43 | .664 | −1.03 | 0.66 | ||||

| Age2 | −0.66 | 0.51 | .197 | .281 | −1.67 | 0.34 | 0.52 | 0.01 | 0.17 | .970 | .970 | −0.33 | 0.34 | .00 |

| Pull hair | ||||||||||||||

| Age | 0.31 | 1.46 | .833 | −2.56 | 3.18 | −0.57 | 0.40 | .154 | −1.35 | 0.21 | ||||

| Age2 | −0.36 | 0.57 | .528 | .660 | −1.49 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.09 | 0.16 | .561 | .935 | −0.22 | 0.40 | .00 |

| Hit or smack | ||||||||||||||

| Age | 5.93 | 1.40 | <.001 | 3.20 | 8.67 | 0.69 | 0.47 | .145 | −0.24 | 1.62 | ||||

| Age2 | −2.02 | 0.56 | <.001 | <.001 | −3.12 | −0.92 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.19 | .403 | .906 | −0.52 | 0.21 | .01 |

| Pinch | ||||||||||||||

| Age | 0.35 | 1.32 | .792 | −2.24 | 2.93 | −0.21 | 0.56 | .713 | −1.31 | 0.89 | ||||

| Age2 | −0.01 | 0.53 | .978 | .978 | −1.04 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 0.07 | 0.22 | .750 | .970 | −0.36 | 0.50 | .00 |

| Hurt animals | ||||||||||||||

| Age | 4.12 | 1.62 | .011 | 0.94 | 7.29 | 0.49 | 0.53 | .354 | −0.54 | 1.52 | ||||

| Age2 | −1.52 | 0.64 | .017 | .057 | −2.77 | −0.27 | 0.22 | −0.16 | 0.22 | .453 | .906 | −0.58 | 0.26 | .00 |

| Bite | ||||||||||||||

| Age | 3.10 | 1.30 | .017 | 0.56 | 5.64 | 0.48 | 0.45 | .283 | −0.40 | 1.36 | ||||

| Age2 | −1.07 | 0.52 | .039 | .078 | −2.08 | −0.06 | 0.34 | −0.17 | 0.17 | .307 | .906 | −0.51 | 0.16 | .01 |

| Push | ||||||||||||||

| Age | 3.42 | 1.60 | .033 | 0.27 | 6.56 | 0.07 | 0.51 | .898 | −0.93 | 1.06 | ||||

| Age2 | −0.88 | 0.61 | .149 | .248 | −2.08 | 0.32 | 0.41 | −0.02 | 0.19 | .926 | .970 | −0.40 | 0.36 | .00 |

| Throw | ||||||||||||||

| Age | 6.17 | 1.57 | <.001 | 3.08 | 9.26 | 1.24 | 0.46 | 0.07 | 0.34 | 2.15 | ||||

| Age2 | −1.85 | 0.61 | .002 | .010 | −3.04 | −0.65 | 0.16 | −0.40 | 0.18 | .029 | .290 | −0.76 | −0.04 | .03 |

| Swipe | ||||||||||||||

| Age | 3.35 | 1.33 | .012 | 0.75 | 5.94 | 0.60 | 0.49 | .226 | −0.37 | 1.56 | ||||

| Age2 | 1.12 | 0.52 | .033 | .078 | −2.14 | −0.09 | 0.33 | −0.21 | 0.19 | .271 | .906 | −0.58 | 0.16 | .01 |

Age scaled as years;

restricted to cases with non-zero values.

In Model 3 (cubic), the binary and continuous PA variables were regressed on age, age2, and age3. No behavior, binary or continuous, had a significant cubic relation with age. We do not report the coefficients.

The significant age trends in PA are plotted in the top (binary) and bottom (continuous) panels of the Figure.

Discussion

Our results suggest that nearly all parents are faced with physically aggressive behavior in the 6- to 24-month age range. Individually, the prevalences of each PA behavior ranged from approximately 26% (hurt animals) to 70% (hit or smack someone). On average, when PA behaviors occurred, parents reported that they happened approximately 1–3 days per week. Several statistically significant age trends were found.

Several maturational forces (e.g., capacity for anger, physical motor maturity, conflict with caregivers) can be expected to increase the performance of PA in infancy and toddlerhood. In line with this logic, most significant age trends suggested increases in the prevalence and/or frequency of PA between 6 and 24 months. Such increases were found for the prevalences of hitting (peaking at 18 months), kicking, and pushing people, as well as throwing objects at (peaking at 20 months) and swiping at people without making contact. We further found that hitting and throwing objects at people became increasingly frequent with age; more dramatically so for hitting, which rose from nearly 1–3 days a week at 6 months to nearly 4–6 days a week at 24 months. The findings on the prevalences of hitting and pushing people were consistent with prior research, as were the year two findings on kicking people.6,7 The year one increase in the prevalence of kicking, however, stood in contrast to prior findings indicating a slight decrease between 8 and 15 months.7

Yet not all PA behaviors increased with age. Hair pulling, in particular, exhibited pronounced decreases in prevalence and frequency. It was the most common behavior at 6 months, reminiscent of the findings reported in two prior studies at 6 and 8 months.5,7 As in the study of Lorber et al, hair pulling also became much less prevalent with age, as predicted.7 Among children who pull others’ hair, the behavior became less frequent as well, dropping from nearly 4–6 days a week at 6 months to nearly 1–3 days a week at 24 months. As predicted, scratching people decreased in frequency as well, although less dramatically than did hair pulling. The prevalence of scratching was not significantly associated with age.. As previously suggested,7 we suspect that hair pulling and scratching are either exploratory behaviors that are more common earlier in infancy due to motor and physical immaturity, and/or younger children are more often held and thus have more opportunities to scratch caregivers and pull their hair.

No age-related trends in the prevalence or frequency of pinching and biting people and hurting animals were detected. Across all PA behaviors, as well as the present and prior 6,7 studies, findings on biting are the most mixed. Our analysis of pinching, which had no significant age trends, as a distinct behavior is novel.

At least four limitations are important to consider. First, this study is limited by its lack of observational measures. Behavior observation would reduce subjectivity in reporting, however, its use comes with its own limitations. Chiefly, reliance on observed instances of PA would likely underestimate the prevalence of aggression, given the typically short length of observation (e.g., minutes to hours) contrasted to the present results’ suggestion that most individual PA behaviors happen on 1–3 days per week. Other methods, such as ecological momentary assessment, may prove useful in reducing recall bias and continuing to use parents as informants. Second, the cross-sectional design did not allow us to model behavior change within individuals. On the other hand, the present design enabled us to identify month-by-month changes in the prevalence and frequency of PA – such as curvilinear trends in hitting and throwing – that might have been missed by the assessment spacing typical of longitudinal studies (e.g., multi-month intervals between assessments). Third, sample selection bias is possible. The marriage/cohabitation rate in the sample was somewhat higher than national norms25 for parents of newborns and we eliminated nearly 10% of the sample for failing to correctly answer a question that assessed participants’ attention to the survey. Correspondingly, the point estimates for our results are certainly colored by an unknown degree of error relative to the population of all American 6- to 24-month-olds. Lastly, a larger sample would yield more power, with precisely estimated normed percentiles that pediatricians can use to identify children with clinically significant levels of aggression at any given age.

At well-child visits, clinicians can reasonably reassure a parent concerned about their child’s early physically aggressive behavior that it is normative, even as early as 6 months. Moreover, when a child exhibits a given PA behavior, parents can expect it to occur at least weekly. Hitting in particular is likely to be experienced more often (most days of a given week), and by a supermajority of parents (≥80%) at its peak at around 1.5 years. Additionally, anticipatory guidance can be provided regarding the expected increase in PA, with some of these behaviors in fact peaking before the “terrible twos.”

PA is normal in the first few years of life. That said, the early years clearly are the best time for parents and providers to intervene before child behavior patterns and unhealthy parental discipline strategies become ingrained and stabilize. Children’s ongoing exposure to some types of dysfunctional parenting (e.g., corporal punishment) is often stable 26 and associated with multiple adverse health outcomes.27,28 In this context, the physician can play a pivotal role to educate the parents about how to respond to PA and other behavior problems with healthy discipline strategies. Parents desire for information about parenting from their pediatrician more than any other person or profession.29 Pediatricians can use existing resources30,31 to educate parents about appropriate strategies such as setting limits and redirecting behavior and avoiding responses such as threatening, yelling, and spanking.9

Finally, we wish to stress our topographical approach to defining PA by its objective behavioral characteristics 33, rather than one that requires intent to harm or a means-end calculation of the instrumental value of PA by the child 34. Such cognitive features are particularly unlikely to characterize infantile PA. Some parents, however, may interpret their child’s PA as intentional, malicious attacks indicative of a behavior problem. Interpretations such as these may depend on parents’ psychological characteristics35 and/or culturally imbued values.36 Clinical emphasis of the near ubiquity of PA as a feature of early development can be used to assuage such parents of their concerns, while encouraging appropriate responses to these normative challenges.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Statistically Significant Age Trends for Individual Aggressive Behaviors. Predicted probabilities (top panel) and mean frequencies (bottom panel) for behaviors with statistically significant age trends; means restricted to cases with non-zero values. Prevalence based on behavior present in the past month; frequency , SD, minimum, and maximum based on non-zero values only; frequency response choices are 0 (Never), 1 (Rarely [less than once a week]), 2 (Some [1–3] days of the week), 3 (Most [4–6] days of the week), 4 (Every day of the week), and 5 (Many times each day). Because a natural log transformation is applied to continuous values in two-part regression models, plotted predicted values for the continuous variables were transformed into their original scaling by multiplying the exponentiated predicted values by the Duan smearing factor.32

Acknowledgments

Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (DE025980). The study sponsor was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing of this manuscript, nor the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations:

- US

United States of America

- N

number of participants

- ,

mean

- SD

standard deviation

- CBR

Child Behavior Record

- FDR

false discovery rate

- R2

coefficient of determination

- ΔR2

change in R2 increment

- OR

odds ratio

- Ora

adjusted odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- B

unstandardized regression coefficient

- SE

standard error

- P

p-value

- PFDR

p-value corrected for false discovery rate

- χ2

chi square

Footnotes

Data Statement:

Data sharing statement available at www.jpeds.com.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Côté SM, Vaillancourt T, Leblanc JC, Nagin DS, Tremblay RE. The development of physical aggression from toddlerhood to pre-adolescence: a nationwide longitudinal study of Canadian children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2006;34:71–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Côté SM, Vaillancourt T, Barker ED, Nagin D, Tremblay RE. The joint development of physical and indirect aggression: Predictors of continuity and change during childhood. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19:37–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Trajectories of physical aggression from toddlerhood to middle childhood: predictors, correlates, and outcomes. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2004;69:1–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alink LR, Mesman J, Van Zeijl J, et al. The early childhood aggression curve: development of physical aggression in 10- to 50-month-old children. Child Dev. 2006;77:954–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hay DF, Perra O, Hudson K, et al. Identifying early signs of aggression: psychometric properties of the Cardiff Infant Contentiousness Scale. Aggress Behav. 2010;36:351–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nærde A, Ogden T, Janson H, Zachrisson HD. Normative development of physical aggression from 8 to 26 months. Dev Psychol. 2014;50:1710–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorber MF, Del Vecchio T, Slep AM. The development of individual physically aggressive behaviors from infancy to toddlerhood. Dev Psychol. 2018;54:601–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tremblay RE, Nagin DS, Séguin JR, et al. Physical aggression during early childhood: Trajectories and predictors. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stein MT, Perrin EL. Guidance for effective discipline. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. Pediatrics. 1998; 101:723–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Combs-Orme T, Holden Nixon B, Herrod HG. Anticipatory guidance and early child development: pediatrician advice, parent behaviors, and unmet needs as reported by parents from different backgrounds. Clin Pediatr. 2011;50:729–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olson LM, Inkelas M, Halfon N, Schuster MA, O’Connor KG, Mistry R. Overview of the content of health supervision for young children: reports from parents and pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1907–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tremblay RE, Nagin DS. The developmental origins of physical aggression in humans In: Tremblay RE, Hartup WW, Archer J. eds. Developmental Origins of Aggression. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005: 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braungart-Rieker JM, Hill-Soderlund AL, Karrass J. Fear and anger reactivity trajectories from 4 to 16 months: the roles of temperament, regulation, and maternal sensitivity. Dev Psychol. 2010;46:791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. WHO Motor Development Study: windows of achievement for six gross motor development milestones. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2006;450:86–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomasello M, Carpenter M, Call J, Behne T, Moll H. Understanding and sharing intentions: the origins of cultural cognition. Behav Brain Sci. 2005;28:675–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biringen Z, Emde RN, Campos JJ, Appelbaum MI. Affective reorganization in the infant, the mother, and the dyad: the role of upright locomotion and its timing. Child Dev. 1995;66:499–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adolph KE, Berger SE. Physical and motor development In: Bornstein MH, Lamb ME, eds. Developmental Science: An Advanced Textbook. 5th ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006:223–81. [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S. Census Bureau. 2011–2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. http://factfinder2.census.gov. Published December 8, 2016. Accessed May 15, 2017.

- 19.Lorber MF, Del Vecchio T, Slep AM. Infant externalizing behavior as a self-organizing construct. Dev Psychol. 2014;50:1854–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hay DF, Mundy L, Roberts S, et al. Known risk factors for violence predict 12-month-old infants’ aggressiveness with peers. Psychol Sci. 2011;22:1205–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wakschlag LS, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Choi SW, et al. Advancing a multidimensional, developmental spectrum approach to preschool disruptive behavior. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:82–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.M thén LK, M thén BO. M l s User’s G ide. 8th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olsen MK, Schafer JL. A two-part random-effects model for semicontinuous longitudinal data. J Am Stat Assoc. 2001;96:730–45. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curtin SC, Ventura SJ, Martinez GM. Recent declines in nonmarital childbearing in the United States (No. 2014). US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacKenzie MJ, Nicklas E, Brooks-Gunn J, Waldfogel J. Spanking and children’s externalizing behavior across the first decade of life: evidence for transactional processes. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44:658–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gershoff ET, Grogan-Kaylor A. Spanking and child outcomes: Old controversies and new meta-analyses. J Fam Psychol. 2016;30:453–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Afifi TO, Ford D, Gershoff ET, et al. Spanking and adult mental health impairment: The case for the designation of spanking as an adverse childhood experience. Child Abuse Negl. 2017;71:24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor CAW, Moeller W, Hamvas L, Rice JC. Parents’ professional sources of advice regarding child discipline and their use of corporal punishment. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2013;52:147–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scholer SJ, Hudnut-Beumler J, Dietrich MS. A brief primary care intervention helps parents develop plans to discipline. Pediatrics. 2010;125: e242–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chavis A, Hudnut-Beumler J, Webb MW, Neely JA, Bickman L, Dietrich MS, Scholer SJ. A brief intervention affects parents’ attitudes toward using less physical punishment. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37:1192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hertz T Heteroskedasticity-robust elasticities in logarithmic and two-part models. Appl Econ Lett. 2010;17:225–28. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tremblay RE. The development of aggressive behaviour during childhood: What have we learned in the past century? Int J Behav Dev. 2000;24:129–41. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coie JD, Dodge KA. Aggression and antisocial behavior In Damon W & Eisenberg N (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (Vol. 3, pp. 779–862). Toronto: Wiley; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slep AMS, O’Leary SG. Multivariate models of mothers’ and fathers’ aggression toward their children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:739–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bornstein MH, Putnick DL, Lansford JE. Parenting attributions and attitudes in cross-cultural perspective. Parenting. 2011;11: 214–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.