The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and associated response have undoubtedly had a dramatic multidimensional impact on healthcare services globally, severely disrupting care for many chronic diseases [1, 2]. Direct impact on communicable diseases, such as tuberculosis (TB), especially in developing countries disproportionally affected by TB, is not yet fully understood but is very likely to put national TB programmes under immense pressure and lead to an increase in TB deaths of 8–20% in the near future [3–5]. This predicted increase is largely caused by delays in diagnosis and treatment of new TB cases due to non-pharmaceutical interventions implemented nationally and globally, in order to contain virus transmission [3, 6–8]. Combined COVID-19 and TB infection also poses a challenge from various perspectives [9]. It is anticipated that the number of co-infected patients increases as the pandemic progresses.

Short abstract

Sustainable support from healthcare bodies is needed to preserve TB laboratory capacity, and maintain personnel and skills, to minimise negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on laboratory services severely disrupted in the early months of pandemic https://bit.ly/38camaL

To the Editor:

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and associated response have undoubtedly had a dramatic multidimensional impact on healthcare services globally, severely disrupting care for many chronic diseases [1, 2]. Direct impact on communicable diseases, such as tuberculosis (TB), especially in developing countries disproportionally affected by TB, is not yet fully understood but is very likely to put national TB programmes under immense pressure and lead to an increase in TB deaths of 8–20% in the near future [3–5]. This predicted increase is largely caused by delays in diagnosis and treatment of new TB cases due to non-pharmaceutical interventions implemented nationally and globally, in order to contain virus transmission [3, 6–8]. Combined COVID-19 and TB infection also poses a challenge from various perspectives [9]. It is anticipated that the number of co-infected patients increases as the pandemic progresses.

In the information note issued on 12 May 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) urged member states to maintain essential services for people affected by TB during the COVID-19 pandemic [10], recognising the potentially devastating effect of the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated response on TB programmes [11]. Laboratory diagnostic services, considered a cornerstone of any country's capacity to manage TB, are likely to be severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and associated response due to re-allocation of resources. Data on actual disruption of TB laboratory services as well as potential medium- and long-term consequences of such a disruption are currently lacking.

In order to better understand the challenges experienced by TB reference laboratories in Europe and explore opportunities for support, we conducted a survey on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on TB and nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) laboratory diagnostic services using the infrastructure of the European Reference Laboratory Network for TB (ERLTB-Net-2). This network comprises 31 national TB reference laboratories (NRLs) representing all European Union/European Economic Area member states and the UK. Laboratories were invited to submit their responses through an online platform using a structured questionnaire comprising five sections (laboratory details, operational impact, workload, contingency arrangements and direct involvement in COVID-19 response) [12]. No person-identifiable data was collected. Laboratories were asked to provide information for four different monthly intervals, starting from 11 March 2020, when COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by WHO. Responses were received from 30/31 laboratories (96.8% response rate).

All NRLs continued to operate as such over the study period (11 March 2020 to 11 June 2020). However, all laboratories experienced an impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, ranging from minor to very significant during at least one of the four monthly intervals. Laboratory operations seemed to be most severely affected in April when 17/30 laboratories (56.7%) defined the impact as “very significant” and “significant”. This gradually fell to 46.7% and 33.3% in the period to 11 June, and the number of laboratories reporting minor or no impact increased from six (20%) in April to 14 (46.7%) in June.

The most severely affected activities were training and research and development (R&D), with the disruption peaking in April 2020 (reported by 23 and 15 laboratories, respectively). The pandemic response has also led to an increase in turnaround times, suspension of selected services (for example drug susceptibility testing for NTM) and reduced access to external quality assessment (EQA) schemes due to selected scheme suspension or delays in shipment of EQA specimen panels. The situation gradually improved in May and June as services were adapting to a “new normal” but training, R&D, and access to EQA schemes remained severely affected and turnaround times did not go back to normal. Some laboratories started to receive samples re-directed from other laboratories, most likely as a part of the national emergency response to COVID-19. This number was highest in April, when seven laboratories reported receiving samples from other organisations.

In the 4 months covered by our study, between 30 and 40% of the laboratories reported problems associated with adapting to new requirements, for example physical distancing or working remotely. Problems with procuring supplies and reagents peaked in April 2020. Staff unavailability linked to either COVID-19-related sickness or self-isolation, lockdowns, as well as re-deployment, affected operations of nearly 30% of the laboratories in March and April. In seven laboratories (23.3%) issues related to staff re-deployment and procurement still persisted in June 2020. A smaller number of laboratories (<10%) experienced problems procuring personal protective equipment, laboratory space constraints (as some sections had been re-allocated to virology services) and overall wellbeing of staff members, including mental health issues related to prolonged shielding, self-isolation or lockdown restrictions.

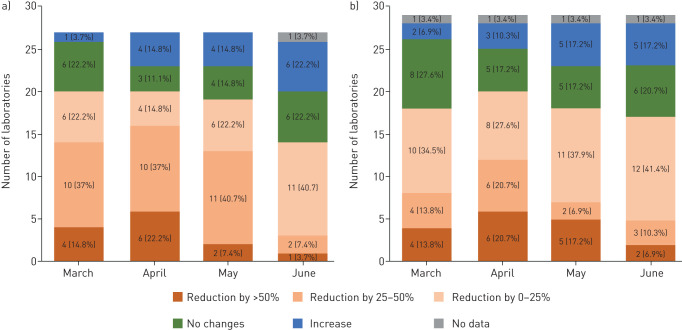

Nearly all NRLs across Europe experienced a sharp reduction of workload in both primary and reference activities, including drug susceptibility testing (figure 1). This was most apparent in April, when 16 and 12 laboratories (59.3% and 41.4% of those providing primary and reference services, respectively) saw numbers of incoming specimens reduced by >25%. In 12 and 11 laboratories, respectively, primary and reference services workload returned to and/or exceeded normal levels by June but the situation had not fully stabilised in more than half of the laboratories. Contingency plans have been activated in six laboratories only (19.4%).

FIGURE 1.

Reduction of workload in European tuberculosis national reference laboratories (NRLs), March to June 2020. Numbers indicate number of TB NRLs experiencing relevant workload reductions in specified months. a) Primary services comprising examination of primary specimens. b) Reference services comprising examination of mycobacterial cultures. Months on diagrams refer to the 11 March, 11 April, 11 May and 11 June 2020.

Many European TB NRLs continue to be directly involved in the COVID-19 response through provision of laboratory testing, including detection of viral RNA, antibody testing, contact tracing, or essential research and development activities, thus contributing to scaling up COVID-19 testing [13]. Only a third (nine laboratories) reported receiving support from the authorities, including additional funding, staff and/or new equipment, to ensure stable functionality of NRLs.

Through our survey, covering the first 4 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, we established that European TB NRLs' core functionality was generally preserved, thus maintaining critical capacity to manage TB reference laboratory services nationally and internationally. However, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on TB NRL functionality has been substantial.

In the short-term, services provided by European TB NRLs will continue to be affected by ongoing restrictions, lockdowns and limited staff availability, as well as procurement issues, resulting in suspension of specific services and increase in turnaround times. Notably, our survey highlighted that R&D and training activities are being de-prioritised in favour of other activities seen as essential during a pandemic; this should be considered a warning sign and likely to have a significant knock-on effect in the medium and long term, limiting the abilities of NRLs to respond to ongoing and future TB-related threats.

The results of our survey complement earlier studies on clinical TB services [8, 11, 14] and demonstrate that the most severe disruption to key TB NRL services occurred in the beginning of the pandemic and coincided with a significant drop in the number of specimens received. By June, most aspects of TB NRLs activities had not returned to normal, and both primary and reference services workload remained significantly lower compared to the pre-pandemic period, highlighting the major impact of COVID-19 currently experienced by public healthcare systems in many European countries. TB NRLs and other TB diagnostic laboratories are facing other challenges, including biosafety risks related to potential COVID-19 exposure when processing primary specimens. Sustainable support from national healthcare authorities and international bodies is urgently needed to preserve TB reference capacity, and maintain personnel and skills, to minimise medium- and long-term negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on TB diagnostic capacity. The current situation warrants further research into long-term impact on TB laboratory services, focusing on both quantitative and qualitative aspects of service disruption and workload.

Shareable PDF

Footnotes

The ERLTB-Net-2 study participants are: Alexander Indra, Austria; Anabel Abela, Malta; Anne Torunn Mengshoel, Norway; Despo Pieridou, Cyprus; Edita Vasiliauskienė, Lithuania; Elizabeta Bachiyska, Bulgaria; Ewa Augustynowicz-Kopeć, Poland; Florian Maurer, Germany; Gudrun Svanborg Hauksdottir, Iceland; Hanna Soini, Finland; Inga Norvaisa, Latvia; Lanfranco Fattorini, Italy; Ljiljana Žmak, Croatia; Manca Zolnir-Dovc, Slovenia; Margaret Fitzgibbon, Ireland; Mathys Vanessa, Belgium; Melinda Medgyaszai, Hungary; Monika Polanova, Slovakia; Monique Perrin, Luxembourg; Norah Easy, UK; Panayotis Ioannidis, Greece; Rita Macedo, Portugal; Roxana Mihaela Coriu, Romania; Sofia Samper, Spain; Tiina Kummik, Estonia; Troels Lillebaek, Denmark; Věra Dvořáková, Czech Republic.

Conflict of interest: V. Nikolayevskyy reports grants from ECDC, during the conduct of the study.

Conflict of interest: Y. Holicka has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: D. van Soolingen has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: M.J. van der Werf has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: C. Ködmön has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: E. Surkova has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: D. Hillemann has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: R. Groenheit has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: D. Cirillo has nothing to disclose.

Support statement: This study has received funding from ECDC (grant ECDC/GRANT/2018/001). Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Chudasama YV, Gillies CL, Zaccardi F, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on routine care for chronic diseases: a global survey of views from healthcare professionals. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2020; 14: 965–967. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. COVID-19 Significantly Impacts Health Services for Noncommunicable Diseases. www.who.int/news-room/detail/01-06-2020-covid-19-significantly-impacts-health-services-for-noncommunicable-diseases Date last updated: 1 Jun 2020.

- 3.McQuaid CF, McCreesh N, Read JM, et al. The potential impact of COVID-19-related disruption on tuberculosis burden. Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 2001718. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01718-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandy C, Takarinda KC, Timire C, et al. Preparing national tuberculosis control programmes for COVID-19. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2020; 24: 634–636. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.20.0200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buonsenso D, Iodice F, Sorba Biala J, et al. COVID-19 effects on tuberculosis care in Sierra Leone. Pulmonology 2020; in press [ 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2020.05.013]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogan AB, Jewell BL, Sherrard-Smith E, et al. Potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2020; 8: e1132–e1141. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30288-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zumla A, Marais BJ, McHugh TD, et al. COVID-19 and tuberculosis—threats and opportunities. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2020; 24: 757–760. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.20.0387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ong CWM, Migliori GB, Raviglione M, et al. Epidemic and pandemic viral infections: impact on tuberculosis and the lung: a consensus by the World Association for Infectious Diseases and Immunological Disorders (WAidid), Global Tuberculosis Network (GTN), and members of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Study Group for Mycobacterial Infections (ESGMYC). Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 2001727. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01727-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tadolini M, Codecasa LR, Garcia-Garcia JM, et al. Active tuberculosis, sequelae and COVID-19 co-infection: first cohort of 49 cases. Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 2001398. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01398-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. World Health Organization (WHO) Information Note: Tuberculosis and COVID-19. www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/tuberculosis/infonote-tb-covid-19.pdf Date last updated: 12 May 2020.

- 11.Migliori GB, Thong PM, Akkerman O, et al. Worldwide effects of coronavirus disease pandemic on tuberculosis services, January–April 2020. Emerg Infect Dis 2020; 26: 2709–2712. doi: 10.3201/eid2611.203163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.https://surveys.phe.org.uk/TakeSurvey.aspx?SurveyID=96KM87m21#.

- 13.Homolka S, Paulowski L, Andres S, et al. Two pandemics, one challenge—leveraging molecular test capacity of tuberculosis laboratories for rapid COVID-19 case-finding. Emerg Infect Dis 2020; 26: 2549–2554. doi: 10.3201/eid2611.202602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magro P, Formenti B, Marchese V, et al. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic on tuberculosis treatment outcome in Northern Italy. Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 2002665. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02665-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This one-page PDF can be shared freely online.

Shareable PDF ERJ-03890-2020.Shareable (423.7KB, pdf)