Abstract

Background

Individual studies have reported widely variable rates for VTE and bleeding among hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Research Question

What is the incidence of VTE and bleeding among hospitalized patients with COVID-19?

Methods

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, 15 standard sources and COVID-19-specific sources were searched between January 1, 2020, and July 31, 2020, with no restriction according to language. Incidence estimates were pooled by using random effects meta-analyses. Heterogeneity was evaluated by using the I2 statistic, and publication bias was assessed by using the Begg and Egger tests.

Results

The pooled incidence was 17.0% (95% CI, 13.4-20.9) for VTE, 12.1% (95% CI, 8.4-16.4) for DVT, 7.1% (95% CI, 5.3-9.1) for pulmonary embolism (PE), 7.8% (95% CI, 2.6-15.3) for bleeding, and 3.9% (95% CI, 1.2-7.9) for major bleeding. In subgroup meta-analyses, the incidence of VTE was higher when assessed according to screening (33.1% vs 9.8% by clinical diagnosis), among patients in the ICU (27.9% vs 7.1% in the ward), in prospective studies (25.5% vs 12.4% in retrospective studies), and with the inclusion of catheter-associated thrombosis/isolated distal DVTs and isolated subsegmental PEs. The highest pooled incidence estimate of bleeding was reported for patients receiving intermediate- or full-dose anticoagulation (21.4%) and the lowest in the only prospective study that assessed bleeding events (2.7%).

Interpretation

Among hospitalized patients with COVID-19, the overall estimated pooled incidence of VTE was 17.0%, with higher rates with routine screening, inclusion of distal DVT, and subsegmental PE, in critically ill patients and in prospective studies. Bleeding events were observed in 7.8% of patients and were sensitive to use of escalated doses of anticoagulants and nature of data collection. Additional studies are required to ascertain the significance of various thrombotic events and to identify strategies to improve patient outcomes.

Trial Registry

PROSPERO; No.: CRD42020198864; URL: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/.

Key Words: bleeding, COVID-19, DVT, pulmonary embolism, VTE

Abbreviations: CAT, catheter-associated thrombosis; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; IDDVT, isolated distal DVT; ISSPE, isolated subsegmental pulmonary embolism; PE, pulmonary embolism; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

FOR EDITORIAL COMMENT, SEE PAGE 908

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a viral illness caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), results in substantial respiratory pathology and also causes important manifestations outside the pulmonary parenchyma.1,2 COVID-19 may predispose patients to venous thromboembolic events (DVT and/or pulmonary embolism [PE]) due to hypoxia, excessive inflammation, platelet activation, endothelial dysfunction, and stasis.3 Accumulating evidence suggests that hospitalized patients with COVID-19 may have a high incidence of VTE, including those receiving standard thromboprophylaxis according to guidelines for acutely ill medical patients.4, 5, 6, 7

However, an accurate estimate of the incidence of VTE in hospitalized patients diagnosed with COVID-19 remains unclear, with incidence rates reported between 4.8% and 85%.5 , 8, 9, 10, 11 This variability might have been influenced by the type of events counted, the type of testing for VTE, assessment setting, and the use and type of thromboprophylaxis. Furthermore, the assessment of PE in patients with COVID-19 is conflated by the presence of immunothrombosis.12 It is likely that in some patients with COVID-19, local inflammation in the lungs with subsequent endothelial inflammation, complement activation, thrombin generation, platelet and leukocyte recruitment, and the initiation of innate and adaptive immune responses culminate in in situ small pulmonary vessel thrombosis.

In addition to an increased risk of thrombosis, patients with COVID-19 might be at risk of excess bleeding due to factors such as imbalances in platelet production and destruction, coagulation factor consumption in the setting of severe inflammation, and use of antiplatelet or anticoagulant agents.13 A recent retrospective study, which included 144 critically ill patients primarily receiving standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, found a major bleeding event rate of 5.6%.14

Comprehensive assessment of the thrombotic and hemorrhagic event rates is critical in the thorough assessment of the disease course for COVID-19 and for considering strategies to mitigate patient outcomes. Our goal, therefore, was to conduct a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the overall incidence of VTE and bleeding among hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Materials and Methods

We prospectively submitted the systematic review protocol for registration on PROSPERO (CRD42020198864) (e-Appendix 1). We followed the Reporting Checklist for Meta-analyses of Observational Studies (MOOSE)15 to conduct and report this systematic review (e-Table 1).

Selection Criteria and Search Strategy

From January 1, 2020, to July 31, 2020, we included observational studies such as cohort and cross-sectional studies in any geographical area evaluating the incidence of VTE and/or bleeding among hospitalized patients with World Health Organization-defined confirmed or probable COVID-19. Studies enrolling < 10 consecutive patients initially hospitalized for COVID-19 were excluded.

We searched MEDLINE (using the Ovid platform), PubMed, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (using the Ovid platform), the Cochrane Library, COVID-19 Open Research Dataset Challenge, COVID-19 Research Database (World Health Organization), Epistemonikos (COVID-19 Living Overview of the Evidence platform), EPPI Centre living systematic map of the evidence, and reference lists of included papers. Preprint servers (bioRxiv, medRxiv, and Social Science Research Network First Look) and coronavirus resource centers of the Lancet, JAMA, and the New England Journal of Medicine (e-Appendix 2) were hand-searched. The search was not limited by language. The search strategy is available in e-Appendix 2.

Data Collection

We screened titles and abstracts, reviewed full texts, and extracted data. Risk of bias was assessed by two authors (D. J. and A. G.-S.) and independently using standardized prepiloted forms. Disagreements were resolved by discussion within the wider team (P. R., B. B., and M. M.).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the incidence of nonfatal or fatal VTE during hospitalization for COVID-19, expressed as the proportion of patients with a diagnosis of VTE. VTE included upper and lower limb DVT and PE diagnosed by using accepted imaging tests, either following clinical suspicion or by routine screening. The secondary outcome was the incidence of bleeding during hospitalization for COVID-19. The incidence of major bleeding (including fatal bleeds) was also determined. Definitions of major bleeding were according to definitions in the individual studies. The outcomes data from the first available time point identified as a primary end point from each study were incorporated into the primary analysis.

Data Analysis

Because of high heterogeneity (as expected and observed), pooled data on the incidence of VTE and major bleeding were analyzed by using a random effects (DerSimonian and Laird method) model approach. Statistical heterogeneity was measured by using the Higgins I 2 statistic.16 , 17 The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used to rate risk of bias for comparative nonrandomized studies corresponding to each study’s design (cohort or cross-sectional).18 , 19 The Begg rank correlation method was used to assess for publication bias.

Prespecified Subgroup Analyses

Data for subgroup effects were analyzed according to VTE type (ie, DVT vs PE), as well as setting (ward vs ICU), type of assessment for VTE (ie, screening vs clinical diagnosis), intensity of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis (no pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis [arbitrarily predefined as ≤ 40% of the study population receiving any pharmacologic prophylaxis] vs standard-dose thromboprophylaxis [arbitrarily predefined as ≥ 70% of the study population receiving standard-dose thromboprophylaxis] vs intermediate-dose thromboprophylaxis or therapeutic anticoagulation), geographical area (North America vs Europe vs rest of the world), and study design (prospective vs retrospective). We also analyzed the incidence of PE and DVT after excluding episodes of isolated subsegmental PE (ISSPE) and catheter-associated thrombosis (CAT)/isolated distal DVT (IDDVT), respectively.

Prespecified Sensitivity Analyses

Two sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the robustness of the study findings. First, outcomes were analyzed from the longest available follow-up points in studies reporting outcomes at multiple time points to ensure no significant changes in outcome estimates. Second, supplemental analyses with inverse variance fixed effects models were run. Analyses were conducted by using Stata version 14.2 (StataCorp).

Results

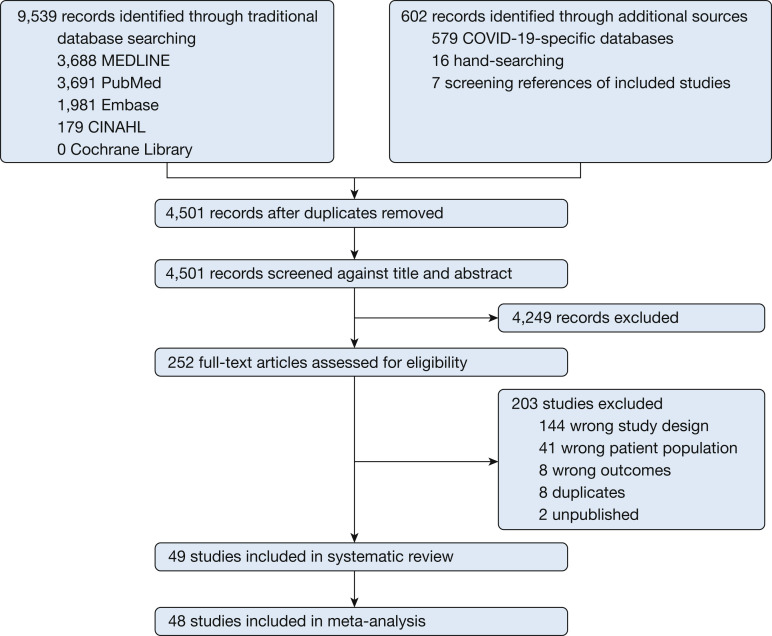

The searches yielded 10,141 citations. After duplicates were removed and the titles and abstracts reviewed, 9,889 articles were excluded. Of the remaining 252 studies, 203 were excluded after reviewing the full-text manuscript. A total of 49 studies reporting the incidence of venous thrombosis (n = 44), bleeding (n = 1), or both (n = 4) were included in the review.4 , 5 , 8, 9, 10, 11 , 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 61, 62 Two studies included overlapping patient populations,5 , 39 and only outcomes data from the first publication were considered for the analyses (Fig 1 ).

Figure 1.

Study selection. CINAHL = Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Descriptive Characteristics

This review is based on a pooled sample of 18,093 patients with reported information related to VTE, 1,273 of whom experienced a VTE event (47 studies),4 , 5 , 8, 9, 10, 11 , 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 , 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51 and a pooled sample of 1,411 patients with reported information related to bleeding, 148 of whom experienced a bleeding event (five studies).8 , 36 , 50 , 51 , 60 The sample sizes ranged widely across studies (median, 108 patients; range, 10-1,477). Among the 47 studies that reported information related to VTE, eight (17%) were conducted in the United States,8 , 22 , 37 , 39 , 43 , 48 , 50 , 59 32 (68%) in Europe,4 , 5 , 10 , 11 , 20 , 21 , 23 , 26 , 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 , 40, 41, 42 , 44 , 46 , 47 , 49 , 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58 , 61 and seven (15%) elsewhere.9 , 24 , 25 , 27 , 45 , 60 , 62 The most common study design was retrospective (33 of 47 [70%]),4 , 8 , 10 , 11 , 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 , 27 , 29, 30, 31, 32 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 39, 40, 41 , 43, 44, 45, 46 , 48 , 50 , 54, 55, 56 , 58, 59, 60 followed by prospective (n = 10 [21%])5 , 28 , 36 , 42 , 47 , 49 , 52 , 53 , 57 , 61 and cross-sectional (n = 4 [9%]).9 , 26 , 33 , 62 Twenty-one studies (21 of 47; [45%]) were conducted exclusively in the ICU setting,4 , 5 , 9 , 10 , 21 , 25 , 27 , 29 , 32 , 35, 36, 37 , 40 , 42 , 43 , 49 , 55 , 57 , 59 , 61 , 62 whereas 10 studies (23%) only enrolled patients in the ward setting20 , 23 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 44 , 46 , 47 , 53 , 56 (Table 1 ). None of the studies identified by this systematic review had VTE and bleeding events independently adjudicated.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Study | No. | Country | Setting (No.) | Design | Assessment for VTE (No.) | Screening Method | Type of VTE | Bleeding Assessment | Intensity of Pharmacologic Thromboprophylaxis (%) | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Samkari et al8 | 400 | United States | Ward (256) ICU (144) |

Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | … | SVT/DVT/PE | Yes (WHO grading system) | None (2) Standard dose (89) Intermediate dose (9) |

8 |

| Artifoni et al20 | 71 | France | Ward | Retrospective | Screening for DVT (71) Clinical diagnosis for PE (71) |

Lower limb ultrasound | DVT/PE | No | Weight-adjusted (99) | 9 |

| Beun et al21 | 75 | The Netherlands | ICU | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | DVT/PE | No | NA | 6 |

| Bilaloglu et al22 | 3,334 | United States | Ward (2,505) ICU (829) |

Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | DVT/PE | No | Standard dose | 7 |

| Cattaneo et al23 | 388 | Italy | Ward | Retrospective | Screening (64) Clinical diagnosis (324) |

Lower limb ultrasound | DVT | No | Standard dose | 8 |

| Chen et al24 | 1,008 | China | NA | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | PE | No | NA | 7 |

| Chen et al25 | 88 | China | ICU | Retrospective | Screening (88) | Ultrasound | DVT | No | Standard dose | 8 |

| Criel et al26 | 82 | Belgium | Ward (52) ICU (30) |

Cross-sectional | Screening (82) | Upper and lower limb ultrasound | DVT | No | None (4) Standard dose (60) Intermediate dose (37) |

7 |

| Cui et al27 | 81 | China | ICU | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | DVT/PE | No | None | 6 |

| Demelo-Rodriguez et al28 | 156 | Spain | Ward | Prospective | Screening (if D-dimer 1,000 ng/mL) (156) | Lower limb ultrasound | DVT | No | Standard dose | 8 |

| Desborough et al29 | 66 | United Kingdom | ICU | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | DVT/PE | No | Standard dose | 8 |

| Dubois-Silva et al30 | 171 | Spain | Ward | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | PE | No | Standard dose | 9 |

| Fauvel et al31 | 2,878 | France | Ward | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | PE | No | NA | 8 |

| Fraissé et al32 | 92 | France | ICU | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | DVT/PE | NA | Standard dose (47) Full dose (therapeutic) (53) |

8 |

| Grandmaison et al33 | 58 | Switzerland | Ward (29) ICU (29) |

Cross-sectional | Screening (58) | Neck, upper and lower limb ultrasound | DVT | No | None (12) Standard dose (82) Full dose (therapeutic) (6) |

8 |

| Grillet et al34 | 280 | France | NA | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | PE | No | NA | 6 |

| Hékimian et al35 | 51 | France | ICU | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | PE | No | NA | 5 |

| Helms et al36 | 150 | France | ICU | Prospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | DVT/PE | Yes (not reported) | Standard dose (70) Full dose (therapeutic) (30) |

9 |

| Hippensteel et al37 | 91 | United States | ICU | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | DVT/PE | No | NA | 7 |

| Klok et al5 | 184 | Netherlands | ICU | Prospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | DVT/PE | No | NA | 7 |

| Klok et al38 | 184 | Netherlands | ICU | Prospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | DVT/PE | No | NA | 7 |

| Koleilat et al39 | 3,404 | United States | NA | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | DVT | No | NA | 7 |

| Llitjos et al40 | 26 | France | ICU | Retrospective | Screening (26) | Lower limb ultrasound | DVT | No | Standard dose (31) Full dose (therapeutic) (69) |

8 |

| Lodigiani et al41 | 388 | Italy | Ward (327) ICU (61) |

Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | DVT/PE | No | None (14) Standard dose (45) Intermediate dose (22) Full dose (therapeutic) (20) |

9 |

| Longchamp et al42 | 25 | Switzerland | ICU | Prospective | Screening for DVT (25) Clinical diagnosis for PE (25) |

Lower limb ultrasound | DVT/PE | No | Standard dose | 9 |

| Maatman et al43 | 109 | United States | ICU | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | DVT/PE | No | Standard dose | 9 |

| Mazzaccaro et al44 | 32 | Italy | Ward | Retrospective | Screening (32) | Upper and lower limb ultrasound, and CTPA | DVT/PE | No | NA | 7 |

| Mei et al45 | 256 | China | Ward (211) ICU (45) |

Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | DVT/PE | No | NA | 9 |

| Mestre- Gómez et al46 | 452 | Spain | Ward | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | PE | No | NA | 5 |

| Middeldorp et al11 | 198 | Netherlands | Ward (123) ICU (75) |

Retrospective | Screening (55) Clinical diagnosis (143) |

Lower limb ultrasound | DVT/PE | No | Standard dose (62) Intermediate dose (38) |

9 |

| Minuz et al47 | 10 | Italy | Ward | Prospective | Screening (10) | CTPA | PE | No | NA | 7 |

| Moll et al48 | 210 | United States | Ward (108) ICU (102) |

Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | … | DVT/PE | No | Standard dose | 8 |

| Nahum et al49 | 34 | France | ICU | Prospective | Screening (34) | Lower limb ultrasound | DVT | No | NA | 8 |

| Patell et al50 | 399 | United States | NA | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | DVT/PE | Yes (ISTH criteria) | None (7) Standard dose (67) Intermediate dose (22) Full dose (therapeutic) (38) |

9 |

| Pesavento et al51 | 324 | Italy | Ward | Retrospective | NA | ... | NA | Yes (ISTH criteria) | Standard dose (74) Intermediate dose (26) |

9 |

| Poissy et al4 | 107 | France | ICU | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | PE | No | NA | 6 |

| Ren et al9 | 48 | China | ICU | Cross-sectional | Screening (48) | Lower limb ultrasound | DVT | No | Standard dose | 7 |

| Rieder et al52 | 49 | Germany | Ward (41) ICU (8) |

Prospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | PE | No | NA | 8 |

| Santoliquido et al53 | 84 | Italy | Ward | Prospective | Screening (84) | Lower limb ultrasound | DVT | No | Standard dose | 9 |

| Stoneham et al54 | 274 | United Kingdom | NA | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | DVT/PE | No | NA | 5 |

| Tavazzi et al55 | 54 | Italy | ICU | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | DVT/PE | No | Standard dose | 5 |

| Thomas et al10 | 63 | United Kingdom | ICU | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | DVT/PE | No | Standard dose | 8 |

| Trimaille et al56 | 289 | France | Ward | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | DVT/PE | No | None (11) Standard dose (59) Intermediate dose (11) Full dose (therapeutic) (20) |

8 |

| Voicu et al57 | 56 | France | ICU | Prospective | Screening (56) | Ultrasound | DVT | No | Standard dose | 8 |

| Whyte et al58 | 1,477 | United Kingdom | Ward (1,255) ICU (222) |

Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | PE | No | Standard dose | 7 |

| Wright et al59 | 44 | United States | ICU | Retrospective | Clinical diagnosis | ... | DVT/PE | No | NA | 4 |

| Xu et al60 | 138 | China | Ward (123) ICU (15) |

Retrospective | Screening for ICU patients (15) Clinical diagnosis for ward patients (123) |

Lower limb ultrasound | DVT | Yes (not reported) | None (70) Standard dose (30) |

8 |

| Zerwes et al61 | 20 | Germany | ICU | Prospective | Screening (20) | Lower limb ultrasound | DVT | No | None (40) Standard dose (30) Intermediate dose (15) Full dose (therapeutic) (15) |

6 |

| Zhang et al62 | 143 | China | ICU | Cross-sectional | Screening (143) | Lower limb ultrasound | DVT | No | None (63) Standard prophylaxis (37) |

8 |

CTPA = CT pulmonary angiogram; ISTH = International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis; NA = not available; PE = pulmonary embolism; SVT = superficial vein thrombosis; WHO = World Health Organization.

The mean age was consistently between 52 and 71 years. The proportion of male subjects ranged from 46% to 81%. Approximately 0% to 12% of patients had a history of VTE, and up to 24% of patients had cancer. The follow-up duration varied from 2 to 55 days (e-Table 2). In 19 studies (19 of 31 [61%]), clinicians used standard thromboprophylaxis for ≥ 70% of the patients8, 9, 10 , 20 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 28, 29, 30 , 33 , 36 , 42 , 43 , 48 , 53 , 55 , 57 , 58; in four studies (4 of 31 [13%]), clinicians prescribed any kind of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis for ≤ 40% of the study population.27 , 60, 61, 62

With respect to VTE assessment, 13 studies (13 of 47 [28%]) systematically examined all patients for VTE (screening).9 , 25 , 26 , 28 , 33 , 40 , 44 , 47 , 49 , 53 , 57 , 61 , 62 VTE was suspected based on clinical or laboratory parameter evolution in 29 studies (29 of 47 [62%]),4 , 5 , 8 , 10 , 21 , 22 , 24 , 27 , 29, 30, 31, 32 , 34, 35, 36, 37 , 39 , 41 , 43 , 45 , 46 , 48 , 50 , 52 , 54, 55, 56 , 58 , 59 and five studies combined both modalities to assess for VTE11 , 20 , 23 , 42 , 60 (Table 1).

Risk of Bias Results

Scores on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for the studies ranged from 4 to 9 (maximum, 9), with a higher score indicating a lower risk of bias. Twenty-eight studies (57%) scored 8 or above and were considered to be at low risk of bias.8 , 10 , 11 , 20 , 23 , 25 , 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 , 36 , 40, 41, 42, 43 , 45 , 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53 , 56 , 57 , 60 , 62 A full assessment is presented in e-Table 3.

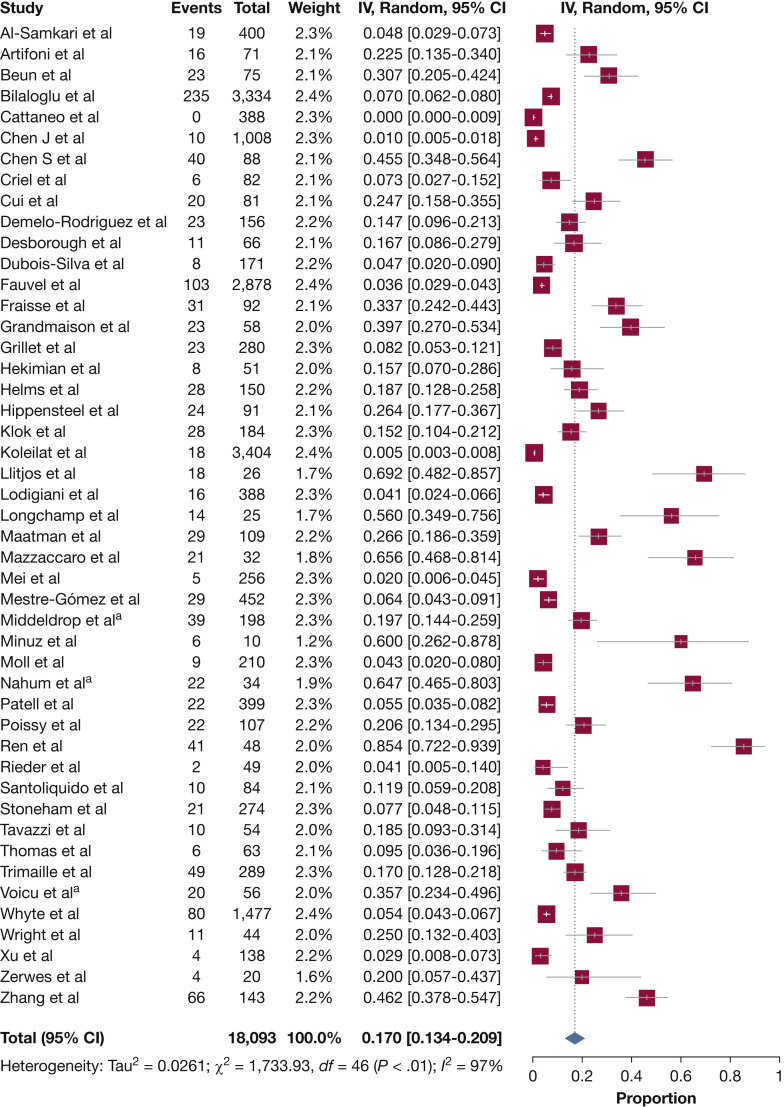

Meta-analysis of the Incidence of VTE

Table 2 presents the results of overall and subgroup meta-analyses. Estimates for the population-based studies ranged from 0% to 85.4% (Fig 2 ), and the random effects overall pooled-estimated incidence of VTE was 17.0% (95% CI, 13.4 to 20.9), with high heterogeneity (I 2 = 97%; P < .001). e-Figure 1 shows some evidence of publication bias, as indicated by visual inspections of the funnel plots and by the Egger test for small study effects for the primary outcome (bias coefficient for the main analysis, –0.003; 95% CI, –0.001 to –0.004; P = .001).

Table 2.

Incidence of VTE and Bleeding Using Random Effects Meta-analysis and Subgroup Meta-analysis

| Variable | No. of Articles | No. of Participants | No. of Cases | Incidence (95% CI) | I2, % | Subgroup Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global analysis for VTE | ||||||

| VTE | 47 | 18,093 | 1,273 | 17.0 (13.4-20.9) | 97 | NA |

| Subgroup analyses for VTE | ||||||

| Type of VTE | ||||||

| DVT | 36 | 11,566 | 614 | 12.1 (8.4-16.4) | 97 | .09 |

| PE | 32 | 13,424 | 649 | 7.1 (5.3-9.1) | 93 | |

| Type of assessment for VTE | ||||||

| Screening | 18 | 1,067 | 332 | 33.1 (21.3-46.0) | 94 | <.0001 |

| Clinical diagnosis | 34 | 17,122 | 941 | 9.8 (7.4-12.6) | 96 | |

| Setting | ||||||

| Ward | 20 | 9,350 | 458 | 7.1 (4.8-9.8) | 93 | <.0001 |

| ICU | 31 | 3,122 | 731 | 27.9 (22.1-34.1) | 92 | |

| Design | ||||||

| Prospective | 10 | 768 | 157 | 25.5 (16.0-36.3) | 89 | <.0001 |

| Retrospective | 33 | 16,994 | 980 | 12.4 (9.4-15.9) | 97 | |

| Geographical location | ||||||

| North America | 8 | 7,991 | 367 | 9.5 (4.4-16.2) | 98 | .15 |

| Europe | 32 | 8,340 | 720 | 17.9 (13.6-22.7) | 96 | |

| Rest of world | 7 | 1,762 | 149 | 23.7 (6.2-47.9) | 99 | |

| Intensity of thromboprophylaxis | ||||||

| None | 4 | 382 | 94 | 21.0 (2.8-48.9) | 97 | .97 |

| Standard dose | 19 | 7,008 | 622 | 18.2 (12.6-24.5) | 97 | |

| Intermediate or therapeutic dose | 8 | 1,549 | 204 | 19.4 (10.5-30.2) | 95 | |

| After exclusion of patients with CAT/IDDVT (for DVT) and ISSPE (for PE) | ||||||

| DVT | 36 | 11,566 | 437 | 6.2 (4.1-8.7) | 95 | .02 |

| PE | 34 | 13,620 | 594 | 5.5 (4.0-7.1) | 91 | |

| Global analysis for bleeding | ||||||

| Bleeding | 5 | 1,411 | 148 | 7.8 (2.6-15.3) | 95 | NA |

| Major bleeding | 5 | 1,411 | 75 | 3.9 (1.2-7.9) | 90 | NA |

| Subgroup analysis for bleeding | ||||||

| Setting | ||||||

| Ward | 3 | 703 | 46 | 5.6 (1.9-10.9) | … | .48 |

| ICU | 3 | 309 | 16 | 4.4 (1.1-9.3) | … | |

| Design | ||||||

| Prospective | 1 | 150 | 4 | 2.7 (0.7-6.7) | ... | <.001 |

| Retrospective | 4 | 1,261 | 144 | 9.4 (3.2-18.3) | 95 | |

| Intensity of thromboprophylaxis | ||||||

| None | 1 | 138 | 6 | 4.4 (1.6-9.2) | ... | <.001 |

| Standard dose | 3 | 790 | 38 | 4.7 (3.1-6.6) | … | |

| Intermediate or therapeutic dose | 2 | 483 | 104 | 21.4 (17.9-25.2) | … |

CAT = catheter-associated thrombosis; IDDVT = isolated distal DVT; ISSPE = isolated subsegmental pulmonary embolism; NA = not available; PE = pulmonary embolism.

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing the incidence of VTE among hospitalized patients with COVID-19. aShortest assessment period. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; IV = Inverse-Variance.

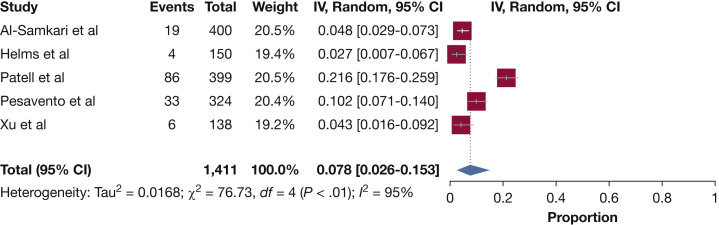

Meta-analysis of the Incidence of Bleeding

Table 2 presents the results of overall and subgroup meta-analyses. Estimates for the population-based studies ranged from 2.7% to 21.6% (Fig 3 ), and the random effects overall pooled-estimated incidence of bleeding was 7.8% (95% CI, 2.6 to 15.3), with high heterogeneity (I 2 = 95%; P < .001). No publication bias was found based on the funnel plot, Egger test (bias coefficient for the main analysis, –2.83; 95% CI, –11.88 to 6.22; P = .39), or Begg test (P = 1.0) (e-Fig 1).

Figure 3.

Forest plot showing the incidence of bleeding among hospitalized patients with COVID-19. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; IV = Inverse-Variance.

Subgroup Analyses

Incidence of VTE

Separate meta-analyses were performed according to the type of VTE (ie, DVT vs PE) (e-Fig 2, Table 2). The graph shows that the incidence of DVT (36 studies; n = 11,566) was 12.1%, whereas the incidence of PE (32 studies; n = 13,424) was 7.1%.

A setting difference in the incidence of VTE was observed between the studies identified in the systematic review. Forty-one studies separately reported the number of ward and ICU patients with and without VTE. The pooled incidence of VTE was 7.1% for patients admitted to the ward and 27.9% for those admitted to the ICU (e-Table 3).

When the studies were categorized according to different diagnostic methods of VTE (ie, screening vs clinical diagnosis), significantly different pooled proportions of VTE were found among different subgroups (e-Fig 2, Table 2). Eighteen of the studies diagnosing VTE were based on screening (n = 1,067), and the combined incidence estimate of VTE was 33.1%. Thirty-four studies were based on clinical diagnosis (n = 17,122), and the incidence estimate of VTE was 9.8%.

When the studies were categorized according to different intensity of thromboprophylaxis (no pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis vs standard-dose thromboprophylaxis vs intermediate-dose thromboprophylaxis or therapeutic anticoagulation), similar pooled proportions of VTE were found among different subgroups (e-Fig 2, Table 2). In four studies, < 40% of the patients received pharmacologic prophylaxis (n = 382), and the combined incidence estimate of VTE was 21.0%. In 19 studies, > 70% of the patients received standard dose prophylaxis (n = 7,008), and the combined incidence estimate of VTE was 18.2%. For the eight studies in which patients received intermediate-dose thromboprophylaxis or therapeutic anticoagulation (n = 1,549),11 , 21 , 26 , 32 , 40 , 41 , 50 , 56 the combined incidence estimate of VTE was 19.4%.

Most of the studies were from Europe (n = 8,340), only eight were from North America (n = 8,014), and seven were from Asia (n = 1,739). The incidence of VTE was 17.9% in Europe, 9.5% in North America, and 23.7% in Asia (e-Fig 2, Table 2). e-Table 4 presents the subgroup meta-analyses according to geographical area.

After excluding patients with a diagnosis of CAT/IDDVT, the combined incidence estimate of DVT was 6.2%. The pooled incidence of PE was 5.5% when patients with ISSPEs were excluded from the analyses.

Incidence of Bleeding

The pooled incidence of major bleeding was 3.9%. The highest pooled incidence estimate of any bleeding was reported for patients receiving intermediate- or full-dose anticoagulation (21.4%) and the lowest was in the only prospective study that assessed bleeding events (2.7%) (Table 2). e-Figure 2 presents the forest plot of the incidence of bleeding across subgroups of patients.

Sensitivity Analyses

When we analyzed outcomes from the longest available follow-up points in studies reporting outcomes at multiple time points, the pooled incidence of VTE was 18.0%. We reconsidered our findings using an inverse variance fixed effects meta-analysis (e-Fig 3). The combined incidence estimate of VTE was 4.7%, and the incidence of bleeding was 9.4%.

Discussion

This comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis from several countries and hospital systems showed that the overall incidence rate of VTE among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 was 17.3%, with roughly two-thirds of the events being DVTs. The results were sensitive to type of assessment for VTE, type of VTE, setting of hospitalization, and nature of data collection, with higher rates with routine screening, inclusion of CAT/IDDVT and ISSPE, in critically ill patients, and in prospective studies. In turn, bleeding events were observed in 7.8% of patients and were sensitive to use of escalated doses of anticoagulants and nature of data collection. Event rates both for VTE and for bleeding are clinically relevant and deserve urgent attention for assessment of the clinical significance and strategies to improve outcomes.

Because of concerns related to thrombotic events, multiple individual studies had reported the rates of VTE in patients with COVID-19. The main strength of this study is that it provided an aggregate estimate. We are cautious not to be overly certain in the precise quantitative estimates of effects, although the qualitative effect and direction are probably of high certainty. Some of the variations across the studies, as shown in our pooled estimates, might be explained by the differences in end point definition, testing strategies, and patients’ baseline risk. Studies that used broader end point definitions (such as inclusion of ISSPEs and CAT/IDDVTs) typically reported higher event rates. Systematic screening is also known to increase the diagnostic yield for detecting VTE.63 Similarly, ICU stay has previously been shown to be a marker of high risk for VTE.64 The lower rates of VTE in retrospective studies, many of which were from the United States, may be indicative of undertesting early in the course of the pandemic when the shortage in personal protective equipment and fluidity of policies in health systems may have precluded appropriate testing in some patients.

A critical unresolved question is whether all these VTE events, if any, correlate with mortality. Analyses from large observational studies will be informative in this regard. It should be specifically determined if events such as ISSPE, which in many cases may reflect immunothrombosis, or IDDVT, carry prognostic significance. This is particularly important considering that the bleeding events are not rare in patients with COVID-19 and will likely increase as a result of intensified antithrombotic therapy.

From a practical perspective, it is important to identify optimal strategies to avoid deterioration and thrombotic events across the spectrum of patients with COVID-19, including outpatients, inpatients in medical wards, and critically ill patients. In this context, results from several ongoing randomized trials will be informative.65 These studies can indicate whether more intense antithrombotic therapy can reduce the rates of VTE but also mortality, which may be driven by VTE as well as microangiopathic thrombotic events and arterial thrombosis.

Studies included in this systematic review found a large proportion of patients with COVID-19 who had isolated distal DVT, catheter-associated thrombosis, and subsegmental PE, supporting the notion that the severe inflammatory response and thromboinflammation may have contributed to such events.66 Although our meta-analysis was not designed to assess treatment efficacy, future studies should determine if immunomodulatory therapies may confer benefit to reduce both the rates of thrombotic events and mortality.67 In this context, reporting of the thrombotic event rates from the trials testing immunomodulatory therapies, including Randomized Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY),68 Intermediate vs Standard-dose Prophylactic Anticoagulation in Critically-ill Patients With COVID-19: An Open Label Randomized Controlled Trial (INSPIRATION-statin),65 and others,69 is highly awaited.

Although the main purpose of the current study was to report on the epidemiology, rather than comparative effectiveness, of health interventions, no association was found between the intensity of thromboprophylaxis and the rate of thrombotic events; however, the rate of clinically relevant bleeding complications among patients who received intermediate- or full-dose anticoagulation exceeded that recorded among those treated with preventive doses. Therefore, results from the ongoing randomized clinical trials are necessary to determine the optimal dose and course of thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19.65 , 70

This study has several limitations. First, in the absence of individual patient data, we were unable to perform a detailed assessment of subgroups or to conduct time-to-event analyses. Second, missing or unreported data in individual studies limited the inferences from aggregate estimates for some of the outcomes. In addition, lack of independent adjudication might have introduced significant biases into this meta-analysis’s estimates of the incidence of VTE and bleeding among hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Third, this study did not assess arterial thrombotic events. The existing literature indicates that the majority of thrombotic events in patients with COVID-19 are in the venous circulation.3 Fourth, the risk of bias tool that we assessed may not have captured all the potential, methodologic limitations of the included studies. It should be noted that prospective, preferentially multicenter and international studies with prospective data collection and similar criteria for outcome assessment will be preferred to provide balanced estimates for disease incidence. Fifth, we were unable to explore the extent of association between incident thrombotic or hemorrhagic events and all-cause mortality. Finally, the high statistical heterogeneity in our study suggests that differences in prevalence estimates across the included studies were determined by factors such as differences in baseline characteristics and baseline risk of VTE, frequency and type of imaging modalities to assess for VTE, setting of hospitalization and acuity of illness, and thromboprophylactic regimens such as type, dose, and duration of antithrombotic therapy. The large difference in results between the random effects and the fixed effects models provides a useful description of the importance of heterogeneity in the individual estimates of included studies; it is for this reason that we had pre-specified to use random effects models for the primary analyses. In addition, small studies might have accounted for this difference,71 and we encourage an updated analysis of incidence rates once several other large-scale studies become available.

Interpretation

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, nearly one in six hospitalized patients with COVID-19 had incident VTE, although the results were sensitive to hospitalization setting, mode of VTE diagnosis, and outcome definitions across studies; the rates of major bleeding were much lower but sensitive to use of escalated doses of anticoagulant agents. Additional studies are required to understand the utility of more potent antithrombotic or immunomodulatory therapies to safely mitigate the risk of thrombotic events, and mortality.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: D. J. is the guarantor of the paper. D. J., B. B., and M. M. were responsible for study concept and design; D. J., A. G.-S., P. R., A. M., B. B., P. R.-A., R. L. M., C. R., B. J. H., and M. M. were responsible for acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and statistical analysis; and D.J. and B.B drafted the manuscript and supervised the study. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, and all authors had full access to the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the analysis.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: B. B. reports that he is a consulting expert (on behalf of the plaintiff) for litigation related to two specific brand models of inferior vena cava filters. The current study is the idea of the investigators and has not been performed at the request of a third party. None declared (D. J., A. G.-S., P. R., A. M., P. R.-A., R. L. M., C. R., B. J. H., M. M.).

Additional information: The e-Appendixes, e-Figures, and e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: The authors have reported to CHEST that no funding was received for this study.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Zaim S., Chong J.H., Sankaranarayanan V., Harky A. COVID-19 and multiorgan response. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2020;45(8):100618. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2020.100618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta A., Madhavan M.V., Sehgal K., et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(7):1017–1032. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0968-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bikdeli B., Madhavan M.V., Jimenez D., et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2950–2973. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poissy J., Goutay J., Caplan M., et al. Lille ICU Haemostasis COVID-19 group Pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients: awareness of an increased prevalence. Circulation. 2020;142(2):184–186. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klok F.A., Kruip M.J.H.A., van der Meer N.J.M., et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernández-Capitán C, Barba R, Díaz-Pedroche MDC, et al. Presenting characteristics, treatment patterns and outcomes among patients with Venous Thromboembolism during hospitalisation for COVID-19 [published online ahead of print October 21, 2020]. Semin Thromb Hemost. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1718402.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Moores L.K., Tritschler T., Brosnahan S., et al. Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of VTE in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2020;158(3):1143–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Samkari H., Karp Leaf R.S., Dzik W.H., et al. COVID and coagulation: bleeding and thrombotic manifestations of SARS-CoV2 infection. Blood. 2020;136(4):489–500. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ren B., Yan F., Deng Z., et al. Extremely high incidence of lower extremity deep venous thrombosis in 48 patients with severe COVID-19 in Wuhan. Circulation. 2020;142(2):181–183. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas W., Varley J., Johnston A., et al. Thrombotic complications of patients admitted to intensive care with COVID-19 at a teaching hospital in the United Kingdom. Thromb Res. 2020;191:76–77. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Middeldorp S., Coppens M., van Haaps T.F., et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(8):1995–2002. doi: 10.1111/jth.14888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McFadyen J.D., Stevens H., Peter K. The emerging threat of (micro)thrombosis in COVID-19 and its therapeutic implications. Circ Res. 2020;127(4):571–587. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colling M.E., Kanthi Y. COVID-19-associated coagulopathy: an exploration of mechanisms. Vasc Med. 2020;25(5):471–478. doi: 10.1177/1358863X20932640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang N., Li D., Wang X. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stroup D.F., Berlin J.A., Morton S.C., et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moskalewicz A., Oremus M. No clear choice between Newcastle-Ottawa Scale and Appraisal Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies to assess methodological quality in cross-sectional studies of health-related quality of life and breast cancer. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;120:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wells G.A., Shea B., O’Connell D., et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 20.Artifoni M., Danic G., Gautier G., et al. Systematic assessment of venous thromboembolism in COVID-19 patients receiving thromboprophylaxis: incidence and role of D-dimer as predictive factors. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(1):211–216. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02146-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beun R., Kusadasi N., Sikma M., Westerink J., Huisman A. Thromboembolic events and apparent heparin resistance in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Int J Lab Hematol. 2020;42(suppl 1):19–20. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.13230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bilaloglu S., Aphinyanaphongs Y., Jones S., Iturrate E., Hochman J., Berger J.S. Thrombosis in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in a New York City Health System. JAMA. 2020;324(8):799–801. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.13372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cattaneo M., Bertinato E.M., Birocchi S., et al. Pulmonary embolism or pulmonary thrombosis in COVID-19? Is the recommendation to use high-dose heparin for thromboprophylaxis justified? Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(8):1230–1232. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1712097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J., Wang X., Zhang S., et al. Characteristics of acute pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19 associated pneumonia from the city of Wuhan. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2020;26 doi: 10.1177/1076029620936772. 1076029620936772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen S, Zhang D, Zheng T, Yu Y, Jiang J. DVT incidence and risk factors in critically ill patients with COVID-19 [published online ahead of print June 30, 2020]. J Thromb Thrombolysis. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-020-02181-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Criel M., Falter M., Jaeken J., et al. Venous thromboembolism in SARS-CoV-2 patients: only a problem in ventilated ICU patients, or is there more to it? Eur Respir J. 2020;56(1):2001201. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01201-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cui S., Chen S., Li X., Liu S., Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(6):1421–1424. doi: 10.1111/jth.14830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demelo-Rodriguez P., Cervilla-Muñoz E., Ordieres-Ortega L., et al. Incidence of asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia and elevated D-dimer levels. Thromb Res. 2020;192:23–26. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Desborough M.J.R., Doyle A.J., Griffiths A., Retter A., Breen K.A., Hunt B.J. Image-proven thromboembolism in patients with severe COVID-19 in a tertiary critical care unit in the United Kingdom. Thromb Res. 2020;193:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dubois-Silva Á., Barbagelata-López C., Mena Á., Piñeiro-Parga P., Llinares-García D., Freire-Castro S. Pulmonary embolism and screening for concomitant proximal deep vein thrombosis in noncritically ill hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Intern Emerg Med. 2020;15(5):865–870. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02416-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fauvel C., Weizman O., Trimaille A., et al. Critical Covid-19 France Investigators Pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients: a French multicentre cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(32):3058–3068. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fraissé M., Logre E., Pajot O., Mentec H., Plantefève G., Contou D. Thrombotic and hemorrhagic events in critically ill COVID-19 patients: a French monocenter retrospective study. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):275. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03025-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grandmaison G., Andrey A., Périard D., et al. Systematic screening for venous thromboembolic events in COVID-19 pneumonia. TH Open. 2020;4(2):e113–e115. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1713167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grillet F., Behr J., Calame P., Aubry S., Delabrousse E. Acute pulmonary embolism associated with COVID-19 pneumonia detected by pulmonary CT angiography. Radiology. 2020;296(3):E186–E188. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hékimian G., Lebreton G., Bréchot N., Luyt C.E., Schmidt M., Combes A. Severe pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients: a call for increased awareness. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):274. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02931-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Helms J., Tacquard C., Severac F., et al. CRICS TRIGGERSEP Group (Clinical Research in Intensive Care and Sepsis Trial Group for Global Evaluation and Research in Sepsis) High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1089–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hippensteel J.A., Burnham E.L., Jolley S.E. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Br J Haematol. 2020;190(3):e134–e137. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klok F.A., Kruip M.J.H.A., van der Meer N.J.M., et al. Confirmation of the high cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19: an updated analysis. Thromb Res. 2020;191:148–150. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koleilat I, Galen B, Choinski K, et al. Clinical characteristics of acute lower extremity deep venous thrombosis diagnosed by duplex in patients hospitalized for coronavirus disease 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Llitjos J.F., Leclerc M., Chochois C., et al. High incidence of venous thromboembolic events in anticoagulated severe COVID-19 patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1743–1746. doi: 10.1111/jth.14869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lodigiani C., Iapichino G., Carenzo L., et al. Humanitas COVID-19 Task Force Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res. 2020;191:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Longchamp A., Longchamp J., Manzocchi-Besson S., et al. Venous thromboembolism in critically ill patients with COVID-19: results of a screening study for deep vein thrombosis. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4(5):842–847. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maatman T.K., Jalali F., Feizpour C., et al. Routine venous thromboembolism prophylaxis may be inadequate in the hypercoagulable state of severe coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(9):e783–e790. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mazzaccaro D., Giacomazzi F., Giannetta M., et al. Non-overt coagulopathy in non-ICU patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 pneumonia. J Clin Med. 2020;9(6):1781. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mei F., Fan J., Yuan J., et al. Comparison of venous thromboembolism risks between COVID-19 pneumonia and community-acquired pneumonia patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40(9):2332–2337. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.314779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mestre-Gómez B., Lorente-Ramos R.M., Rogado J., et al. Infanta Leonor Thrombosis Research Group. Incidence of pulmonary embolism in non-critically ill COVID-19 patients. Predicting factors for a challenging diagnosis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2021;51(1):40–46. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02190-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Minuz P, Mansueto G, Mazzaferri F, et al. High rate of pulmonary thromboembolism in patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020 Nov;26(11):1572-1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Moll M., Zon R.L., Sylvester K.W., et al. VTE in ICU patients with COVID-19. Chest. 2020;158(5):2130–2135. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nahum J., Morichau-Beauchant T., Daviaud F., Echegut P., Fichet J., Maillet J.M., Thierry S. Venous thrombosis among critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patell R., Bogue T., Bindal P., et al. Incidence of thrombosis and hemorrhage in hospitalized cancer patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(9):2349–2357. doi: 10.1111/jth.15018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pesavento R., Ceccato D., Pasquetto G., et al. The hazard of (sub)therapeutic doses of anticoagulants in non-critically ill patients with Covid-19: the Padua province experience. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(10):2629–2635. doi: 10.1111/jth.15022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rieder M., Goller I., Jeserich M., et al. Rate of venous thromboembolism in a prospective all-comers cohort with COVID-19. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(3):558–566. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02202-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Santoliquido A., Porfidia A., Nesci A., et al. GEMELLI AGAINST COVID-19 Group. Incidence of deep vein thrombosis among non-ICU patients hospitalized for COVID-19 despite pharmacological thromboprophylaxis. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(9):2358–2363. doi: 10.1111/jth.14992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stoneham S.M., Milne K.M., Nuttall E., et al. Thrombotic risk in COVID-19: a case series and case-control study. Clin Med (Lond) 2020;20(4):e76–e81. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tavazzi G., Civardi L., Caneva L., Mongodi S., Mojoli F. Thrombotic events in SARS-CoV-2 patients: an urgent call for ultrasound screening. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1121–1123. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06040-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trimaille A., Curtiaud A., Marchandot B., et al. Venous thromboembolism in non-critically ill patients with COVID-19 infection. Thromb Res. 2020;193:166–169. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Voicu S., Bonnin P., Stépanian A., et al. High prevalence of deep vein thrombosis in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(4):480–482. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whyte M.B., Kelly P.A., Gonzalez E., Arya R., Roberts L.N. Pulmonary embolism in hospitalised patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;195:95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wright F.L., Vogler T.O., Moore E.E., et al. Fibrinolysis shutdown correlation with thromboembolic events in severe COVID-19 infection. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;231(2):193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu J, Wang L, Zhao L, Li Q, Gu J, Liang S, Zhao Q, Liu J. Risk assessment of venous thromboembolism and bleeding in COVID-19 patients. Research Square. In press. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-18340/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Zerwes S., Hernandez Cancino F., Liebetrau D., et al. Increased risk of deep vein thrombosis in intensive care unit patients with CoViD-19 infections? Preliminary data. Der Chirurg. 2020;91(7):588–594. doi: 10.1007/s00104-020-01222-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang L., Feng X., Zhang D., et al. Deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Prevalence, risk factors, and outcome. Circulation. 2020;142(2):114–128. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kodadek L.M., Haut E.R. Screening and diagnosis of VTE: the more you look, the more you find? Current Trauma Reports. 2016;2:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boonyawat K., Crowther M.A. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in critically ill patients. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2015;41(1):68–74. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1398386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bikdeli B., Talasaz A.H., Rashidi F., et al. Intermediate versus standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation and statin therapy versus placebo in critically-ill patients with COVID-19: rationale and design of the INSPIRATION/INSPIRATION-S studies. Thromb Res. 2020;196:382–394. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Connors J.M., Levy J.H. Thromboinflammation and the hypercoagulability of COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1559–1561. doi: 10.1111/jth.14849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bikdeli B., Madhavan M.V., Gupta A., et al. Global COVID-19 Thrombosis Collaborative Group Pharmacological agents targeting thromboinflammation in COVID-19: review and implications for future research. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(7):1004–1024. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1713152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19—preliminary report [published online ahead of print July 17, 2020]. N Engl J Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2021436.

- 69.Toniati P., Piva S., Cattalini M., et al. Tocilizumab for the treatment of severe COVID-19 pneumonia with hyperinflammatory syndrome and acute respiratory failure: a single center study of 100 patients in Brescia. Italy. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19(7):102568. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lemos A.C.B., do Espírito Santo D.A., Salvetti M.C., et al. Therapeutic versus prophylactic anticoagulation for severe COVID-19: a randomized phase II clinical trial (HESACOVID) Thromb Res. 2020;196:359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Greco T., Zangrillo A., Biondi-Zoccai G., Landoni G. Meta-analysis: pitfalls and hints. Heart Lung Vessel. 2013;5(4):219–225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.