Abstract

Lung cancer patients are at heightened risk for developing COVID-19 infection as well as complications due to multiple risk factors such as underlying malignancy, anti-cancer treatment induced immunosuppression, additional comorbidities and history of smoking. Recent literatures have reported a significant proportion of lung cancer patients coinfected with COVID-19. Chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir/ritonavir, ribavirin, oseltamivir, remdesivir, favipiravir, and umifenovir represent the major repurposed drugs used as potential experimental agents for COVID-19 whereas azithromycin, dexamethasone, tocilizumab, sarilumab, famotidine and ceftriaxone are some of the supporting agents that are under investigation for COVID-19 management. The rationale of this review is to identify potential drug-drug interactions (DDIs) occurring in lung cancer patients receiving lung cancer medications and repurposed COVID-19 drugs using Micromedex and additional literatures. This review has identified several potential DDIs that could occur with the concomitant treatments of COVID-19 repurposed drugs and lung cancer medications. This information may be utilized by the healthcare professionals for screening and identifying potential DDIs with adverse outcomes, based on their severity and documentation levels and consequently design prophylactic and management strategies for their prevention. Identification, reporting and management of DDIs and dissemination of related information should be a major consideration in the delivery of lung cancer care during this ongoing COVID-19 pandemic for better patient outcomes and updating guidelines for safer prescribing practices in this coinfected condition.

Key Words: Drug-drug interactions, COVID-19, Lung cancer, QT prolongation, Tyrosine kinase inhibitors, Chemotherapy

Introduction

The coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) or novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has adversely affected the global healthcare system, particularly oncology care. Malignancy and anti-cancer medications such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy can lead to an immunosuppressive state in cancer patients (1,2). Therefore, cancer patients have a heightened risk of developing COVID-19 infection. Recent literatures have reported that lung cancer patients are more susceptible to COVID-19 infection (3,4). Smoking is also associated with a high risk of developing COVID-19 severity among lung cancer patients (5). Limited literatures are available on the incidence/prevalence of COVID-19 infection among lung cancer patients. A nationwide analysis of cancer among 1590 COVID-19 patients from 575 hospitals in 31 provincial regions of China has revealed that 18 cases (1%) had a history of cancer. Lung cancer was the most common type of cancer accounting for 28% (5 cases) of the cancer cases (3). Other studies from Wuhan, China has also revealed that lung cancer was the most common type of cancer in COVID-19 patients (6,7). Results from electronic medical records (EMR) analysis of Mount Sinai Health System (MSHS) on COVID-19 patients in New York City has revealed that 6% of patients (n = 334) had cancer. Among these cancer patients, 6.8% (n = 23) had lung cancer, which was the third highest cancer after breast and prostate cancers (8).

Lung cancer treatment includes long term chemotherapy cycles and drug treatments which upon co-administration with repurposed COVID-19 drugs and other supporting agents used for COVID-19 management could increase the risk for DDIs. DDIs possess significant detrimental effects on patient safety, health economics, and treatment outcomes particularly in patients on polypharmacy (9, 10, 11, 12, 13). A large number of current drugs used in the market for a long period are being tried globally as experimental targets and as supportive care therapies for COVID-19 management since repurposing old drugs offers the advantage of not needing to go through the rigorous procedures of developing a new chemical entity and further drug approval process. However, the results of different trials/studies conducted in different countries have yielded conflicting reports on safety and efficacy issues at various stages and in a different population (14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20). Chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), lopinavir/ritonavir, ribavirin, oseltamivir, remdesivir, favipiravir, and umifenovir are the major COVID-19 repurposed drugs whereas azithromycin, dexamethasone, tocilizumab, sarilumab, famotidine and ceftriaxone are some of the supporting agents that are currently employed as potential experimental targets for COVID-19 treatment (21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27).

There is only sparse information available regarding COVID-19 treatment outcomes in lung cancer patients. Recently, Jacobo R et al. reported 17 cases of lung cancer with COVID-19 infection among 45 cancer patients (37.7%). Among these 17 patients, 8 (47.1%), 2 (11.7%), 1 (5.9%), and 1 (5.9%) patient received hydroxychloroquine+ azithromycin, lopinavir/ritonavir + hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir/ritonavir + hydroxychloroquine + azithromycin, and hydroxychloroquine treatments, respectively. The treatment with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin combination was found to improve the outcome of lung cancer patients with COVID-19, with only 1 death being reported for this treatment (OR 0.04, CI 0.01−0.57, p = 0.018) (28). Luo J et al. reported that 62% and 25% of the lung cancer patients coinfected with COVID-19 (n = 102) were hospitalised and died respectively. Among the hospitalized patients, hydroxychloroquine treatment (73%, n = 35/48) was not associated with improved COVID-19 outcomes (OR for ICU/intubation/DNI 1.39, 95% CI 0.37–4.56, p = 0.7, and OR death 1.03, 95% CI 0.26–3.55, p = 0.99) (29). Considering the risk factors and reported incidence/prevalence pattern, a larger population of lung cancer patients could be anticipated to be infected with COVID-19 infection in the coming days. Therefore, assessment of potential DDIs occurring with the lung cancer medications with the repurposed COVID-19 drugs can provide preliminary knowledge for screening, identification, and management of DDIs in this coinfected condition. In this scenario, we assessed the potential DDIs between the repurposed COVID-19 drugs and lung cancer pharmacotherapies using the drug interaction checker of IBM Micromedex®.

Methods

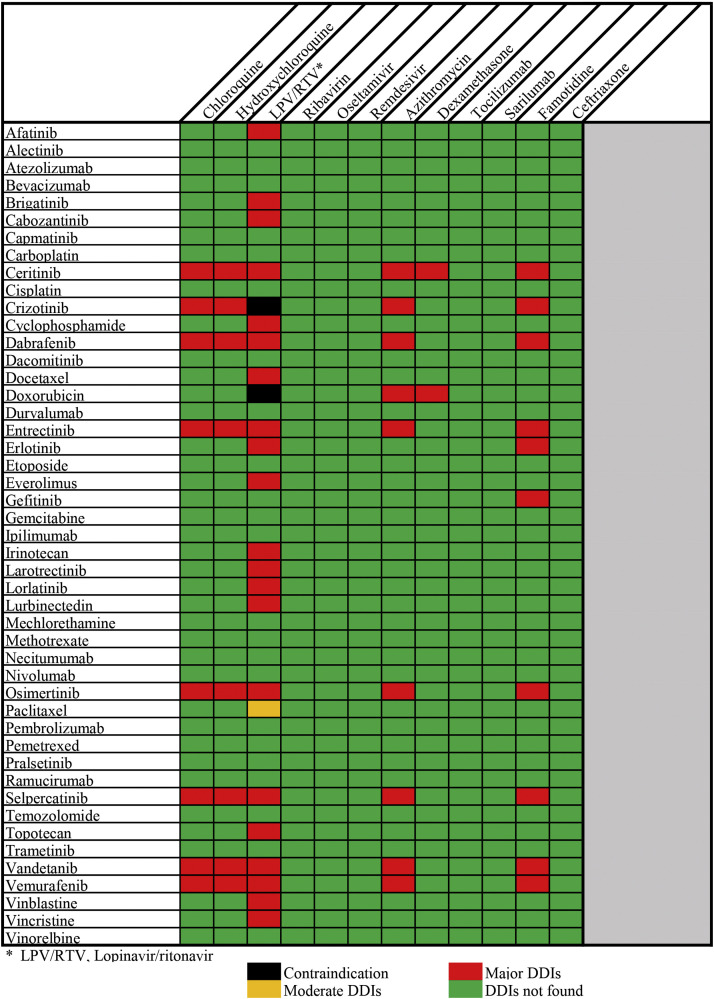

We conducted a search for potential DDIs between lung cancer medications and repurposed COVID-19 drugs using the drug interaction checker of IBM Micromedex® (30). Drugs used in the treatment of lung cancer were compiled from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines® and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved lung cancer drugs (31, 32, 33). The repurposed COVID-19 drugs and supporting agents were compiled from several guidelines and literature search till October 21st 2020 (34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39). The interaction tool in Micromedex provides instant access to DDIs. COVID-19 repurposed drugs and lung cancer medications were selected from the search field and added to the ‘drugs to check’ in the interaction tool. Information on DDIs was manually extracted using Micromedex. Micromedex classifies the severity of DDIs as contraindicated, major, moderate, minor, and unknown. Additionally, Micromedex provides description of all DDIs and clinical management information for certain cases. A total of 61 potential DDIs along with their severity was identified from Micromedex. Additionally, relevant literatures were extracted from PubMed and Google Scholar for gathering information on the mechanism of interaction, clinical consequences, monitoring parameters, and precautions for the DDIs found from the drug interaction checker of Micromedex. We excluded non-scientific commentaries from our review. Only English literatures were included in the review. No DDI data were available for ribavirin, oseltamivir, remdesivir, tocilizumab, sarilumab, and ceftriaxone with lung cancer medications using the Micromedex interaction tool. Favipiravir and umifenovir were not found in the search list of Micromedex interaction tool till 21st October 2020. The severity grading of DDIs (Figure 1 ) was based solely on the results of the drug interaction checker of Micromedex. Micromedex provides a more reliable database for the severity grading of DDIs (40).

Figure 1.

Drug-drug interactions severity chart.

Mechanism of Drug Interactions of Repurposed COVID-19 Drugs with Lung Cancer Pharmacotherapies

Pharmacodynamic Interactions

Pharmacodynamic interactions occur when both drugs affect similar molecular targets or the same physiologic pathways leads to altered efficacy and toxicity. It can be additive, synergistic, or antagonistic (41).

QT Prolongation

As chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir, ritonavir, azithromycin, and famotidine are associated with QT prolongation, sweeping usage of these drugs along with insufficient consideration for concomitant use of other QT prolonging agents could result in an increased frequency of cardiovascular adverse events (42, 43, 44, 45, 46). Further, there is a high prevalence of COVID-19 infection among patients with underlying cardiovascular diseases and COVID-19 infection can also provoke myocardial injury (47). Chloroquine and HCQ are both 4-aminoquinoline agents historically used for malaria (48). Recently these drugs have gained significant attention for their exploratory investigation for COVID-19 treatment (44,49, 50, 51, 52). Chloroquine and HCQ are known to cause cardiotoxicity and QT prolongation (42,53, 54, 55, 56). Lopinavir/ritonavir are human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) protease inhibitors that are under clinical investigation for COVID-19 infection. Evidences have demonstrated their activity against COVID-19 via inhibition of 3-chymotrypsin-like protease (17,21,57,58). Lopinavir/ritonavir are also associated with a potential for causing QT prolongation (57,59). The addition of azithromycin to hydroxychloroquine resulted in superior viral clearance compared to hydroxychloroquine alone in COVID-19 patients (60). However, azithromycin exposure has been reported to cause ventricular arrhythmia, torsades de pointes and sudden cardiac arrest and the FDA has added the related warning information to the package inserts (46,61). Therefore, a careful electrocardiogram (ECG) assessment is advised during azithromycin usage for identifying any signs of QT prolongation (21,46). Concomitant use of azithromycin with hydroxychloroquine can cause a greater change in the QTc prolongation than HCQ alone (44). Reports of favipiravir induced QT prolongation are conflicting (62,63). Invitro reports showed that remdesivir weakly inhibited hERG channel (IC50 value for the inhibitory effect was 28.9 μM), suggesting a potential for probable QT prolongation (64). Famotidine, a histamine-2 receptor antagonist, has been recently considered to be a potential repurposed COVID-19 drug as it has been reported to decrease the composite outcome of death intubation in COVID-19 patients (27). Studies have reported that famotidine administration was associated with prolonged QT interval (65,66).

Multikinase inhibitors (MKIs) such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are commonly used in the management of lung malignancy, particularly in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (41). QT prolongation is one of the major known adverse effects of TKIs (67). Approximately 4% of patients receiving TKIs are associated with QT prolongation (68). QT prolongation is one of the most serious toxicities associated with crizotinib and ceritinib, that are FDA approved for ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase) positive NSCLC patients (67,69,70). 4% of patients receiving osimertinib, an approved drug for EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) T790M mutated NSCLC patients developed QT prolongation (68,71,72). Dabrafenib, which is an approved BRAF (B-Raf proto-oncogene) inhibitor along with entrectinib, an inhibitor of the tyrosine kinases ALK, TRKA/B/C (tropomyosin receptor kinase) and ROS1 (c-ros oncogene1) were reported to cause QT prolongation (73,74). Vandetanib, vemurafenib and selpercatinib were also reported to cause QT prolongation as one of the major adverse effects (75, 76, 77). Co-administration with COVID-19 repurposed drugs with these lung cancer medications can lead to additive effects on QT interval prolongation which may further increase the risk of cardiac arrhythmias and torsades de pointes (78). Careful monitoring, dosage adjustment, withhold/withdrawal of drugs, and/or avoidance of drugs may be required if concomitant medications with the risk of QT prolongation are taken by patients (49,79). Therefore, optimal medication surveillance and regular ECG to monitoring for QT interval prolongation is advised in COVID-19 patients undergoing chemotherapy for lung cancer.

Pharmacokinetic Interactions

Pharmacokinetic interactions occur when one drug influences other drug's absorption, metabolism, distribution, and elimination. Cytochrome P450 (CYP) and its isoenzymes are responsible for most of the drug metabolism and pharmacokinetic DDIs due to altered plasma concentrations (41).

Drug Absorption

Gastrointestinal pH is the most important factor affecting the solubility and exposure of drugs particularly of TKIs such as erlotinib, gefitinib, and selpercatinib. Concomitant administration of histamine H2-receptor antagonists like famotidine may increase stomach pH that can reduce TKI solubility, absorption, and bioavailability. Therefore, the potential for such interactions is clinically important, and apt drug administration time interval management is required (77,80, 81, 82).

Drug Metabolism

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are metabolized into active metabolites in the liver through the N-desethylation pathway mediated by CYP2D6, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and CYP2C8 enzymes (83, 84, 85, 86, 87). Lopinavir undergoes metabolism by CYP3A4 enzymes in both the intestine and the liver and acts as a substrate for P-glycoprotein (P-gp) transporter (88,89). Lopinavir/ritonavir is a strong CYP3A inhibitor and hence can increase the exposure of brigatinib (90). A 50% dose reduction of brigatinib is suggested if concomitant use with strong CYP3A inhibitors is unavoidable (90). Similarly, concomitant use of lopinavir/ritonavir with lung cancer medications like crizotinib and dabrafenib can also increase the plasma concentration of the latter and consequently lead to adverse reactions (73,91). Ritonavir is a very potent inhibitor of CYP3A4 enzyme and hence can increase the plasma concentration of lung cancer medications like ceritinib, everolimus, docetaxel, doxorubicin, entrectinib, and erlotinib that are majorly metabolized by CYP3A4 (41,92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100). Ritonavir may increase lorlatinib and paclitaxel plasma levels due to inhibition of CYP3A-mediated metabolism (101,102). Azithromycin has been shown to be a weak CYP3A4 substrate with no significant ability to induce nor inhibit CYP3A4 activity or organic anion transporting polypeptide (OATP1B1) activity (103, 104, 105).

Dexamethasone is a widely used first-line agent for the prevention and management of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting (106). Dexamethasone is a potent steroid and also an inducer of CYP3A4 (107,108). Therefore, concomitant use with ceritinib (a strong CYP3A inhibitor) should be avoided and close monitoring of side effects is recommended (41). Larotrectinib, cabozantinib, irinotecan, cyclophosphamide, topotecan, and lurbinectedin are metabolized primarily via CYP3A4. Therefore, caution is required when these drugs are used concomitantly with lopinavir or ritonavir and monitor for possible changes in the efficacy or toxicity profile (109,110). Vincristine and vinblastine are CYP3A4 and P-gp substrates. The plasma concentrations of vincristine and vinblastine are likely to be increased when concomitantly administered with protease inhibitors (109,111).

Remdesivir is a novel adenosine analogue therapeutically used for RNA based viruses including the Ebola virus (EBOV) and the Coronaviridae family viruses (24). Remdesivir is an inhibitor of CYP3A4, multidrug resistance-associated protein 4 (MRP4), bile acid export pump (BSEP), OATP1B1, OATP1B3, and sodium-taurocholate cotransporter protein (NTCP) in vitro (64). The plasma concentrations of remdesivir may increase with the concomitant use of strong CYP enzyme or P-gp inducers (112). Favipiravir is a purine nucleic acid analogue which undergoes ribosylation and phosphorylation into an active metabolite favipiravir ibofuranosyl-5′-triphos-phate (T-705RTP) intracellularly (113). T-705RTP interferes with the viral replication process by inhibiting the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (114). Tocilizumab is an interleukin 6 (IL-6) receptor antagonist (115). Early study reports suggest that COVID-19 patients with multiple comorbidities who received tocilizumab had an improved outcome (116,117). Sarilumab is another IL 6 receptor antagonist that is being trialed in a double-blind study (118). Up-regulation of IL-6 reduces the activity of CYP450 enzymes, and blockade of this cytokine may improve CYP function. This may lead to decreased bioavailability of drugs metabolized by CYP enzyme.

As CYP3A4 is responsible for the majority of drug metabolism, it is likely to decrease the bioavailability of other drugs when co-administered with tocilizumab. Thus, caution is required when co-prescribing tocilizumab and CYP-metabolized drugs (119).

Drug Transportation

Drug interactions concerning drug transportation (efflux and uptake) have significant clinical relevance during the administration of TKIs (41). Efflux drug transporters like P-gp belonging to ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 1 and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) plays a crucial role in the occurrence of DDIs (41). The plasma concentration of afatinib (P-gp and BCRP substrate) is increased when it is co-administered with ritonavir which is a strong P-gp and BCRP inhibitor. Therefore, monitoring of adverse effects and staggered dosing, 6 h or 12 h apart from afatinib is recommended in this scenario (41,120). Ritonavir may increase the intracellular accumulation of doxorubicin, a P-gp substrate leading to the systemic toxicity of the latter (97,98). The DDIs of experimental COVID-19 repurposed drugs and supporting agents with various lung cancer medications are shown in Supplementary Table 1 and the severity of DDIs is shown in Figure 1.

Drug Interactions of Repurposed Drugs for COVID-19 with Lung Cancer Supportive Care Pharmacotherapies

In addition to lung cancer medications, several drugs are given as supportive care for lung cancer patients (121). Supportive care drugs are usually used for the treatment of side effects, tumor symptoms, and concomitant diseases. A significant proportion of the patients assumed three or more different drugs in addition to chemotherapy in advanced stages of NSCLC (121). Therefore, we have overviewed potential drug interactions caused by repurposed COVID-19 drugs and some of the major supportive care drugs recommended by NCCN guidelines using the drug interaction checker of IBM Micromedex®. Cancer supportive care drugs were compiled from NCCN recommendations of drugs for adult cancer pain, haemopoietic growth factors, cancer, and chemotherapy induced anemia, distress management, cancer related fatigue, cancer associated venous thromboembolic disease, emesis, immunotherapy related toxicities, and palliative care (122). Methadone is an opioid drug used for cancer pain which is associated with QT prolongation (123). Similarly, antiemesis drugs such as olanzapine, dolasetron, granisetron, ondansetron, and prochlorperazine are also associated with QT prolongation (124, 125, 126, 127). Antipsychotic drugs used in cancer palliative care such as haloperidol, quetiapine, and risperidone may cause prolonged QT interval, serious cardiovascular side effects, and can leads to torsades de pointes and death (124). Other supportive care drugs such as donepezil, octreotide, and metronidazole are also reported to cause QT prolongation (128, 129, 130). Therefore, concomitant use of these supportive care drugs with chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir, ritonavir, azithromycin, and famotidine could result in a potential interaction and an increased frequency of cardiovascular adverse events. Commonly used drugs for cancer pain such as codeine, fentanyl, lidocaine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, and tramadol are majorly metabolized by CYP3A4 (131). CYP3A4 has been considered as a significant enzyme for the metabolism of other supportive care drugs such as midazolam, naloxegol, quetiapine, and zolpidem (132, 133, 134, 135). Therefore, concomitant use of these drugs with strong CYP3A inhibitors such as lopinavir and ritonavir may increase the exposure and risk of adverse effects. Administration of ritonavir along with oral prednisolone may increase systemic corticosteroid exposure and may result in the development of Cushing syndrome (136). Concomitant use of morphine and ritonavir may increase the exposure of morphine and increase the risk of adverse effects (131). Therefore, it is important to recognize potential drug interactions between cancer supportive care drugs and repurposed COVID-19 drugs.

Conclusion

There is a high potential for the occurrence of major DDIs associated with the concomitant use of COVID-19 repurposed treatments with lung cancer medications, with QT prolongation being the most commonly identified DDI. This review is intended to provide an alert for clinicians and pharmacists for developing holistic scientifically interrogative strategies for screening, identification, reporting, and management of potential DDIs in lung cancer patients coinfected with COVID-19 infection. Currently, there is limited data available regarding the DDI profile of certain lung cancer medications with repurposed drugs for COVID-19. Hence, further scientific reports from clinical trials and observational studies are required to provide more concrete data on prevalence, risk factors, severity assessments and clinical management strategies of DDIs between lung cancer medications and repurposed drugs for COVID-19 during this pandemic.

Acknowledgment

Gayathri Baburaj would like to acknowledge DST-INSPIRE Fellowship, Department of Science and Technology, Government of India, New Delhi, India [DST/INSPIRE Fellowship/2018/IF180737] and Levin Thomas is thankful to Dr. TMA Pai PhD Scholarship from Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, India.

(ARCMED_2020_1092)

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcmed.2020.11.006.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Kamboj M., Sepkowitz K.A. Nosocomial infections in patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:589–597. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longbottom E.R., Torrance H.D., Owen H.C. Features of postoperative immune suppression are reversible with interferon gamma and independent of interleukin-6 pathways. Ann Surg. 2016;264:370–377. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang W., Guan W., Chen R. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Passaro A., Peters S., Mok T.S. Testing for COVID-19 in lung cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:832–834. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berlin I., Thomas D., Le Faou A.-L. COVID-19 and smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang L., Zhu F., Xie L. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19-infected cancer patients: A retrospective case study in three hospitals within Wuhan, China. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:894–901. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu J., Ouyang W., Chua M.L. SARS-CoV-2 transmission in cancer patients of a tertiary hospital in Wuhan. medRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Miyashita H., Mikami T., Chopra N. Do Patients with Cancer Have a Poorer Prognosis of COVID-19? An Experience in New York City. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:1088–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mirošević Skvrce N., Macolić Šarinić V., Mucalo I. Adverse drug reactions caused by drug-drug interactions reported to Croatian Agency for Medicinal Products and Medical Devices: a retrospective observational study. Croat Med J. 2011;52:604–614. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2011.52.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khandeparkar A., Rataboli P.V. A study of harmful drug–drug interactions due to polypharmacy in hospitalized patients in Goa Medical College. Perspect Clin Res. 2017;8:180–186. doi: 10.4103/picr.PICR_132_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lazarou J., Pomeranz B.H., Corey P.N. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA. 1998;279:1200–1205. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Arifi M., Abu-Hashem H., Al-Meziny M. Emergency department visits and admissions due to drug related problems at Riyadh military hospital (RMH), Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J. 2014;22:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor R., Jr., V Pergolizzi J., Jr., Puenpatom R.A. Economic implications of potential drug–drug interactions in chronic pain patients. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;13:725–734. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2013.851006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magro G. COVID-19: Review on latest available drugs and therapies against SARS-CoV-2. Coagulation and inflammation cross-talking. Virus Res. 2020;286:198070. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou L., Dai L., Zhang X. Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine: a potential and controversial treatment for COVID-19. Arch Pharm Res. 2020;43:765–772. doi: 10.1007/s12272-020-01258-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang M., Tang T., Pang P. Treating COVID-19 with Chloroquine. J Mol Cell Biol. 2020;12:322–325. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjaa014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao B., Wang Y., Wen D. A trial of lopinavir–ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalil A.C. Treating COVID-19-Off-Label Drug Use, Compassionate Use, and Randomized Clinical Trials During Pandemics. JAMA. 2020;323:1897–1898. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tong S., Su Y., Yu Y. Ribavirin therapy for severe COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56:106114. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang C., Tian L., Liu Y. A promising antiviral candidate drug for the COVID-19 pandemic: A mini-review of remdesivir. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;201:112527. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanders J.M., Monogue M.L., Jodlowski T.Z. Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020;323:1824–1836. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrison C. Coronavirus puts drug repurposing on the fast track. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38:379–381. doi: 10.1038/d41587-020-00003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhai P., Ding Y., Wu X. The epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020:105955. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eastman R.T., Roth J.S., Brimacombe K.R. Remdesivir: A Review of Its Discovery and Development Leading to Emergency Use Authorization for Treatment of COVID-19. ACS Cent Sci. 2020;6:672–683. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guaraldi G., Meschiari M., Cozzi-Lepri A. Tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e474–e484. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30173-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo P., Liu Y., Qiu L. Tocilizumab treatment in COVID-19: A single center experience. J Med Virol. 2020;92:814–818. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mather J.F., Seip R.L., McKay R.G. Impact of Famotidine Use on Clinical Outcomes of Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1617–1623. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobo R., Pangua C., Serrano-Montero G. Covid-19 and lung cancer: A greater fatality rate? Lung Cancer. 2020;146:19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo J., Rizvi H., Preeshagul I.R. COVID-19 in patients with lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:1386–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.IBM Micromedex® IBM Watson Health products Corporation. 2020. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/

- 31.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Non-small cell lung cancer (version 8.2020-September 15,2020) https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf

- 32.National Cancer Institute Drugs Approved for Lung Cancer. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/drugs/lung

- 33.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Small cell lung cancer (version 1.2021- August 11, 2020) https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/sclc.pdf

- 34.National Institute of Health (NIH) COVID-19 treatment guidelines 2020. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/whats-new/

- 35.Canadian Critical Care Society and Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease (AMMI) Canada Clinical management of patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 - Interim guidance. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/clinical-management-covid-19.html

- 36.Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR): advisory on the use of hydroxychloroquine as prophylaxis for SARS-C0V-2 infection. 2020. https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/AdvisoryontheuseofHydroxychloroquinasprophylaxisforSARSCoV2infection.pdf

- 37.National COVID-19 clinical evidence taskforce: living guidelines. Australia. 2020. https://covid19evidence.net.au/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Khan S., Gionfriddo M.R., Cortes-Penfield N. The trade-off dilemma in pharmacotherapy of COVID-19: systematic review, meta-analysis, and implications. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2020;4:1–29. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2020.1792884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National institute for health and care excellence (NICE) COVID-19 rapid guidelines. United Kingdom. 2020. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng163 [PubMed]

- 40.Suriyapakorn B., Chairat P., Boonyoprakarn S. Comparison of potential drug-drug interactions with metabolic syndrome medications detected by two databases. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hussaarts K.G., Veerman G.M., Jansman F.G. Clinically relevant drug interactions with multikinase inhibitors: a review. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2019;11 doi: 10.1177/1758835918818347. 1758835918818347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bustos M.D., Gay F., Diquet B. The pharmacokinetics and electrocardiographic effects of chloroquine in healthy subjects. Trop Med Parasitol. 1994;45:83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khobragade S.B., Gupta P., Gurav P. Assessment of proarrhythmic activity of chloroquine in in vivo and ex vivo rabbit models. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2013;4:116–124. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.110892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mercuro N.J., Yen C.F., Shim D.J. Risk of QT interval prolongation associated with use of hydroxychloroquine with or without concomitant azithromycin among hospitalized patients testing positive for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020:e201834. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anson B.D., Weaver J.G., Ackerman M.J. Blockade of HERG channels by HIV protease inhibitors. Lancet. 2005;365:682–686. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17950-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi Y., Lim H.-S., Chung D. Risk evaluation of Azithromycin-Induced QT prolongation in real-world practice. BioMed Res Int. 2018;2018:1574806. doi: 10.1155/2018/1574806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang J., Zheng Y., Gou X. Prevalence of comorbidities in the novel Wuhan coronavirus (COVID-19) infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verbaanderd C., Maes H., Schaaf M.B. Repurposing Drugs in Oncology (ReDO)—chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as anti-cancer agents. Ecancermedicalscience. 2017;11:781. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2017.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jafari A., Dadkhahfar S., Perseh S. Considerations for interactions of drugs used for the treatment of COVID-19 with anti-Cancer treatments. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2020:102982. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.102982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Solomon V.R., Lee H. Chloroquine and its analogs: a new promise of an old drug for effective and safe cancer therapies. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;625:220–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yao X., Ye F., Zhang M. In vitro antiviral activity and projection of optimized dosing design of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Clin Infect Dis. 2020:ciaa237. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lewis J., Gregorian T., Portillo I. Drug interactions with antimalarial medications in older travelers: a clinical guide. J Travel Med. 2020;27:taz089. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taz089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen C.-Y., Wang F.-L., Lin C.-C. Chronic hydroxychloroquine use associated with QT prolongation and refractory ventricular arrhythmia. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2006;44:173–175. doi: 10.1080/15563650500514558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morgan N.D., Patel S.V., Dvorkina O. Suspected hydroxychloroquine-associated QT-interval prolongation in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Rheumatol. 2013;19:286–288. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31829d5e50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stas P., Faes D., Noyens P. Conduction disorder and QT prolongation secondary to long-term treatment with chloroquine. Int J Cardiol. 2008;127:e80–e82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Giudicessi J.R., Noseworthy P.A., Friedman P.A. Urgent guidance for navigating and circumventing the QTc-prolonging and torsadogenic potential of possible pharmacotherapies for coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:1213–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen F., Chan K., Jiang Y. In vitro susceptibility of 10 clinical isolates of SARS coronavirus to selected antiviral compounds. J Clin Virol. 2004;31:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Soliman E.Z., Lundgren J.D., Roediger M.P. Boosted protease inhibitors and the electrocardiographic measures of QT and PR durations. AIDS. 2011;25:367. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328341dcc0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gautret P., Lagier J.-C., Parola P. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020:105949. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 61.Raschi E., Poluzzi E., Koci A. Macrolides and torsadogenic risk: emerging issues from the FDA pharmacovigilance database. J Pharmacovigilance. 2013;1:104. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chinello P., Petrosillo N., Pittalis S. QTc interval prolongation during favipiravir therapy in an Ebolavirus-infected patient. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0006034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kumagai Y., Murakawa Y., Hasunuma T. Lack of effect of favipiravir, a novel antiviral agent, on QT interval in healthy Japanese adults. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;53:866–874. doi: 10.5414/CP202388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.European Medicines Agency Summary on compassionate use Remdesivir Gilead. 2020. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/summary-compassionate-use-remdesivir-gilead_en.pdf

- 65.Lee K.W., Kayser S.R., Hongo R.H. Famotidine and long QT syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:1325–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yun J., Hwangbo E., Lee J. Analysis of an ECG record database reveals QT interval prolongation potential of famotidine in a large Korean population. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2015;15:197–202. doi: 10.1007/s12012-014-9285-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Raedler L.A. Zykadia (Ceritinib) approved for patients with crizotinib-resistant ALK-positive non–small-cell lung cancer. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8:163–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mok T.S., Wu Y.-L., Ahn M.-J. Osimertinib or platinum–pemetrexed in EGFR T790M–positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:629–640. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kazandjian D., Blumenthal G.M., Chen H.-Y. FDA approval summary: crizotinib for the treatment of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer with anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangements. Oncologist. 2014;19:e5. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Leprieur E.G., Fallet V., Cadranel J. Spotlight on crizotinib in the first-line treatment of ALK-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: patients selection and perspectives. Lung Cancer (Auckl) 2016;7:83–90. doi: 10.2147/LCTT.S99303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sullivan I., Planchard D. Osimertinib in the treatment of patients with epidermal growth factor receptor T790M mutation-positive metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: clinical trial evidence and experience. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2016;10:549–565. doi: 10.1177/1753465816670498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schiefer M., Hendriks L.E., Dinh T. Current perspective: osimertinib-induced QT prolongation: new drugs with new side-effects need careful patient monitoring. Eur J Cancer. 2018;91:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nebot N., Arkenau H.T., Infante J.R. Evaluation of the effect of dabrafenib and metabolites on QTc interval in patients with BRAF V600–mutant tumours. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84:764–775. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Drilon A., Siena S., Ou S.-H.I. Safety and antitumor activity of the multitargeted pan-TRK, ROS1, and ALK inhibitor entrectinib: combined results from two phase I trials (ALKA-372-001 and STARTRK-1) Cancer Discov. 2017;7:400–409. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grande E., Kreissl M.C., Filetti S. Vandetanib in advanced medullary thyroid cancer: review of adverse event management strategies. Adv Ther. 2013;30:945–966. doi: 10.1007/s12325-013-0069-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Uhara H., Kiyohara Y., Tsuda A. Characteristics of adverse drug reactions in a vemurafenib early post-marketing phase vigilance study in Japan. Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20:169–175. doi: 10.1007/s12094-017-1706-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Highlights of prescribing information. RETEVMOTM (selpercatinib) capsules, for oral use Initial U.S. Approval. 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/213246s000lbl.pdf

- 78.Hunt K., Hughes C.A., Hills-Nieminen C. Protease inhibitor–associated qt interval prolongation. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:1544–1550. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Roden D.M., Harrington R.A., Poppas A. Considerations for drug interactions on QTc in exploratory COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) treatment. Circulation. 2020;141:e906–e907. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xu Z.Y., Li J.L. Comparative review of drug-drug interactions with epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;9:5467–5484. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S194870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lam L.H., Capparelli E.V., Kurzrock R. Association of concurrent acid-suppression therapy with survival outcomes and adverse event incidence in oncology patients receiving erlotinib. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;78:427–432. doi: 10.1007/s00280-016-3087-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ohgami M., Kaburagi T., Kurosawa A. Effects of Proton Pump Inhibitor Coadministration on the Plasma Concentration of Erlotinib in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Ther Drug Monit. 2018;40:699–704. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lim H.-S., Im J.-S., Cho J.-Y. Pharmacokinetics of hydroxychloroquine and its clinical implications in chemoprophylaxis against malaria caused by Plasmodium vivax. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1468–1475. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00339-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schrezenmeier E., Dörner T. Mechanisms of action of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine: implications for rheumatology. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16:155–166. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-0372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim K.-A., Park J.-Y., Lee J.-S. Cytochrome P450 2C8 and CYP3A4/5 are involved in chloroquine metabolism in human liver microsomes. Arch Pharm Res. 2003;26:631–637. doi: 10.1007/BF02976712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Projean D., Baune B., Farinotti R. In vitro metabolism of chloroquine: identification of CYP2C8, CYP3A4, and CYP2D6 as the main isoforms catalyzing N-desethylchloroquine formation. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31:748–754. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.6.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ducharme J., Farinotti R. Clinical pharmacokinetics and metabolism of chloroquine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1996;31:257–274. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199631040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.ter Heine R., Van Waterschoot R.A., Keizer R.J. An integrated pharmacokinetic model for the influence of CYP3A4 expression on the in vivo disposition of lopinavir and its modulation by ritonavir. J Pharm Sci. 2011;100:2508–25015. doi: 10.1002/jps.22457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Van Waterschoot R., Ter Heine R., Wagenaar E. Effects of cytochrome P450 3A (CYP3A) and the drug transporters P-glycoprotein (MDR1/ABCB1) and MRP2 (ABCC2) on the pharmacokinetics of lopinavir. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1224–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00759.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tugnait M., Gupta N., Hanley M.J. Effects of Strong CYP2C8 or CYP3A Inhibition and CYP3A Induction on the Pharmacokinetics of Brigatinib, an Oral Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase Inhibitor, in Healthy Volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2019;9:214–223. doi: 10.1002/cpdd.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Teo Y.L., Ho H.K., Chan A. Metabolism-related pharmacokinetic drug− drug interactions with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: current understanding, challenges and recommendations. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79:241–253. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pasin V.P., Pereira A.R., Carvalho K.A. New drugs, new challenges to dermatologists: mucocutaneous ulcers secondary to everolimus. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:S165–S167. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kwo P.Y., Badshah M.B. New hepatitis C virus therapies: drug classes and metabolism, drug interactions relevant in the transplant settings, drug options in decompensated cirrhosis, and drug options in end-stage renal disease. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2015;20:235–241. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Loulergue P., Mir O., Allali J. Possible pharmacokinetic interaction involving ritonavir and docetaxel in a patient with Kaposi's sarcoma. AIDS. 2008;22:1237–1239. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328300ca98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mir O., Dessard-Diana B., Louet A.L.L. Severe toxicity related to a pharmacokinetic interaction between docetaxel and ritonavir in HIV-infected patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69:99–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rudek M.A., Chang C.Y., Steadman K. Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) component ritonavir significantly alters docetaxel exposure. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;73:729–736. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2399-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Berretta M., Caraglia M., Martellotta F. Drug–drug interactions based on pharmacogenetic profile between highly active antiretroviral therapy and antiblastic chemotherapy in cancer patients with HIV infection. Front. Pharmacol. 2016;7:71. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kim T.H., Shin S., Yoo S.D. Effects of phytochemical P-Glycoprotein modulators on the pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of doxorubicin in mice. Molecules. 2018;23:349. doi: 10.3390/molecules23020349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhao D., Chen J., Chu M. Pharmacokinetic-Based Drug–Drug Interactions with Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase Inhibitors: A Review. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2020;14:1663–1681. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S249098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pillai V.C., Venkataramanan R., Parise R.A. Ritonavir and efavirenz significantly alter the metabolism of erlotinib—an observation in primary cultures of human hepatocytes that is relevant to HIV patients with cancer. Drug Metab Dispos. 2013;41:1843–1851. doi: 10.1124/dmd.113.052100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Li W., Sparidans R.W., Wang Y. Oral coadministration of elacridar and ritonavir enhances brain accumulation and oral availability of the novel ALK/ROS1 inhibitor lorlatinib. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2019;136:120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2019.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hendrikx J.J., Lagas J.S., Rosing H. P-glycoprotein and cytochrome P450 3A act together in restricting the oral bioavailability of paclitaxel. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:2439–2447. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Seithel A., Eberl S., Singer K. The influence of macrolide antibiotics on the uptake of organic anions and drugs mediated by OATP1B1 and OATP1B3. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35:779–786. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.014407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Westphal J.F. Macrolide–induced clinically relevant drug interactions with cytochrome P-450A (CYP) 3A4: an update focused on clarithromycin, azithromycin and dirithromycin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;50:285–295. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Polasek T.M., Miners J.O. Quantitative prediction of macrolide drug-drug interaction potential from in vitro studies using testosterone as the human cytochrome P4503A substrate. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:203–208. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Marinella M.A. Routine antiemetic prophylaxis with dexamethasone during COVID-19: Should oncologists reconsider? J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1078155220931921. 1078155220931921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pascussi J.M., Drocourt L., Gerbal-Chaloin S. Dual effect of dexamethasone on CYP3A4 gene expression in human hepatocytes: sequential role of glucocorticoid receptor and pregnane X receptor. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:6346–6358. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.McCune J.S., Hawke R.L., LeCluyse E.L. In vivo and in vitro induction of human cytochrome P4503A4 by dexamethasone. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;68:356–366. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2000.110215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lopinavir; Ritonavir (All Populations Monograph). Clinical Pharmacology powered by ClinicalKey. https://www.elsevier.com/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/990730/Lopinavir,-Ritonavir-Drug-Monograph_3.17.2020.pdf

- 110.Highlights of prescribing information. ZEPZELCATM (lurbinectedin) for injection, for intravenous use Initial U.S. Approval. 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/213702s000lbl.pdf

- 111.Huang R.S., Murry D.J., Foster D.R. Role of xenobiotic efflux transporters in resistance to vincristine. Biomed Pharmacother. 2008;62:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yang K. What do we know about remdesivir drug interactions? Clin Transl Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1111/cts.12815. 10.1111/cts.12815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Du Y.X., Chen X.P. Favipiravir: pharmacokinetics and concerns about clinical trials for 2019-nCoV infection. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020 doi: 10.1002/cpt.1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Furuta Y., Gowen B.B., Takahashi K. Favipiravir (T-705), a novel viral RNA polymerase inhibitor. Antiviral Res. 2013;100 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Scott L.J. Tocilizumab: A Review in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Drugs. 2017;77:1865–1879. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0829-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Michot J.M., Albiges L., Chaput N. Tocilizumab, an anti-IL-6 receptor antibody, to treat COVID-19-related respiratory failure: a case report. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:961–964. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zhang X., Song K., Tong F. First case of COVID-19 in a patient with multiple myeloma successfully treated with tocilizumab. Blood Adv. 2020;4:1307–1310. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.First patient outside U.S. treated in global Kevzara® (sarilumab) clinical trial program for patients with severe COVID-19. https://investor.regeneron.com/index.php/news-releases/news-release-details/first-patient-outside-us-treated-global-kevzarar-sarilumab

- 119.Kim S., Östör A.J., Nisar M.K. Interleukin-6 and cytochrome-P450, reason for concern? Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:2601–2604. doi: 10.1007/s00296-012-2423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wind S., Giessmann T., Jungnik A. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions of afatinib with rifampicin and ritonavir. Clin Drug Investig. 2014;34:173–182. doi: 10.1007/s40261-013-0161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Di Maio M., Perrone F., Gallo C. Supportive care in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1013–1021. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN Guidelines for Supportive Care. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx#supportive

- 123.Isbister G.K., Brown A.L., Gill A. QT interval prolongation in opioid agonist treatment: analysis of continuous 12-lead electrocardiogram recordings. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83:2274–2282. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Stöllberger C., Huber J.O., Finsterer J. Antipsychotic drugs and QT prolongation. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;20:243–251. doi: 10.1097/01.yic.0000166405.49473.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Keller G.A., Ponte M.L., Di Girolamo G. Other drugs acting on nervous system associated with QT-interval prolongation. Curr Drug Saf. 2010;5:105–111. doi: 10.2174/157488610789869256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Moffett P.M., Cartwright L., Grossart E.A. Intravenous Ondansetron and the QT Interval in Adult Emergency Department Patients: An Observational Study. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23:102–105. doi: 10.1111/acem.12836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kim M.D., Eun S.Y., Jo S.H. Blockade of HERG human K+ channel and IKr of guinea pig cardiomyocytes by prochlorperazine. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;544:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Jackson E.G., Stowe S. Lesson of the month 1: Prolonged QT syndrome due to donepezil: a reversible cause of falls? Clin Med (Lond) 2019;19:80–81. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.19-1-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Pivonello R., Muscogiuri G., Holder G. Long-term safety of long-acting octreotide in patients with diabetic retinopathy: results of pooled data from 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 studies. Endocrine. 2018;60:65–72. doi: 10.1007/s12020-017-1448-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Khan Q., Ismail M., Haider I. Prevalence of the risk factors for QT prolongation and associated drug-drug interactions in a cohort of medical inpatients. J Formos Med Assoc. 2019;118:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2018.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Feng X.Q., Zhu L.L., Zhou Q. Opioid analgesics-related pharmacokinetic drug interactions: from the perspectives of evidence based on randomized controlled trials and clinical risk management. J Pain Res. 2017;10:1225–1239. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S138698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wandel C., Böcker R., Böhrer H. Midazolam is metabolized by at least three different cytochrome P450 enzymes. Br J Anaesth. 1994;73:658–661. doi: 10.1093/bja/73.5.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Zhou D., Bui K., Sostek M. Simulation and Prediction of the Drug-Drug Interaction Potential of Naloxegol by Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2016;5:250–257. doi: 10.1002/psp4.12070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Sampson M.R., Cao K.Y., Gish P.L. Dosing Recommendations for Quetiapine When Coadministered With HIV Protease Inhibitors. J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;59:500–509. doi: 10.1002/jcph.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Lee C.M., Jung E.H., Byeon J.Y. Effects of steady-state clarithromycin on the pharmacokinetics of zolpidem in healthy subjects. Arch Pharm Res. 2019;42:1101–1106. doi: 10.1007/s12272-019-01201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Albert N.E., Kazi S., Santoro J. Ritonavir and epidural triamcinolone as a cause of iatrogenic Cushing's syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 2012;344:72–74. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31824ceb2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.