Abstract

Norrie disease (ND) is a rare, X-linked condition of visual and auditory impairment, often presenting with additional neurological features and developmental delays of varying severity. While all affected patients are born blind, or lose their vision in infancy, progressive sensorineural hearing loss develops in the majority of cases and is typically detected in the second decade of life. A range of additional symptoms of ND, such as seizure disorders, typically appear from a young age, but it is difficult to predict the range of symptoms ND patients will experience. After growing up without vision, hearing loss represents the greatest worry for many patients with ND, as they may lose the ability to participate in previously enjoyed activities or to communicate with others.

Dual sensory loss has a physical, psychosocial and financial impact on both patients with ND and their families. Routine monitoring of the condition is required in order to identify, treat and provide support for emerging health problems, leading to a large burden of medical appointments. Many patients need to travel long distances to meet with specialists, representing a further burden on time and finances. Additionally, the rare nature of dual sensory impairment in children means that few clinical environments are designed to meet their needs. Dual Sensory clinics are multidisciplinary environments designed for sensory-impaired children and have been suggested to alleviate the impact of diseases involving sensory loss such as ND.

Here, we discuss the diagnosis, monitoring and management of ND and the impact it has on paediatric patients and their caregivers. We describe the potential for dual sensory clinics to reduce disease burden through providing an appropriate clinical environment, access to multiple clinical experts in one visit, and ease of monitoring for patients with ND.

Keywords: audiology, ophthalmology, deafness

Key Messages.

Norrie disease (ND) is a rare condition of congenital or infantile blindness. In addition, the majority of patients with ND experience progressive sensorineural hearing loss.

Dual sensory loss has a significant impact on ND patients and is associated with communication problems, additional educational needs and feelings of isolation.

Patients with ND require management and monitoring by a range of clinicians and specialists to help them reach their full potential.

It is proposed that dual sensory clinics would alleviate the impact of ND by providing coordinated care by clinical specialists familiar with the disease.

Care by clinicians aware of the needs of ND patients improves the patient experience and can ensure timely and appropriate intervention for hearing loss.

Clinics designed with the needs of sensory impaired children in mind, and with staff trained in effective communication skills, can alleviate the stress of appointments.

Introduction

Norrie disease (ND; OMIM 310600, figure 1) is a rare condition with over 400 cases described, but its prevalence and incidence is unknown.1 ND is caused by mutations in the ND pseudoglioma (NDP) gene, located on the X chromosome, therefore, the vast majority of patients are male. ND is the most severe of a spectrum of vitreoretinopathies including familial exudative vitreoretinopathy, retinopathy of prematurity and Coat’s disease.2

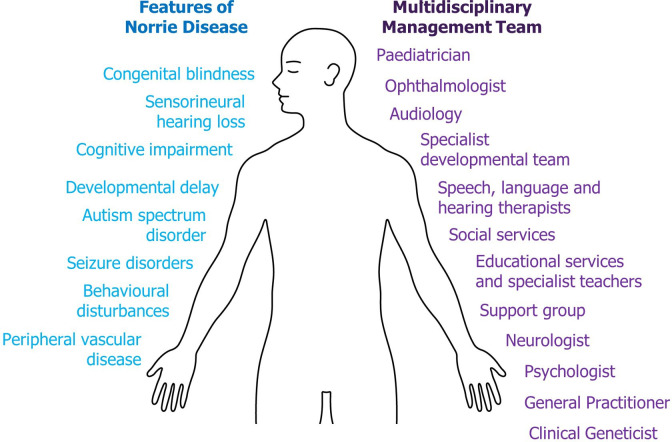

Figure 1.

Features and management of Norrie disease (ND). In addition to blindness and hearing loss, ND can present with a range of other neurological, psychological and systemic features (left), making this a complex disease. Due to its complexity, ND patients should have a multidisciplinary team involved in their care and development (right) in order to support all aspects of life and optimise their chance of success.

Patients with ND typically present with congenital or infantile blindness3; the majority are blind from birth. Ocular signs of the disease are present at birth or develop during early infancy, with clinical examination of the eye often revealing microphthalmia (abnormally small eyes), corneal opacity, vitreous haemorrhage (leakage of blood into the eye), cataracts, dysplastic retinal tissue and retinal detachment.2 Parents may notice a white reflex in their child’s pupils, or that their child fails to respond to light.4–6

Most patients with ND will pass their newborn hearing screen but the majority will experience progressive sensorineural hearing loss.7 Early hearing loss can be asymptomatic, with initial loss of high frequencies progressing to severe symmetric hearing loss, typically by 35 years of age.7 8 Patients consistently report intermittent hearing loss with slow deterioration over time, tinnitus and periods of ‘stuffiness’,7 though speech discrimination is usually well preserved.8 9 Of those with hearing loss, most experience its onset by their mid-20s, with one study reporting the median age of onset was 12 years.7 Referral of patients with ND to audiology after diagnosis is important as regular monitoring allows early intervention from the onset of impairment.

In addition to dual sensory loss, ND is associated with cognitive impairment, neurodevelopmental disorders (eg, autism spectrum disorder [ASD]), peripheral vascular disease (PVD) and seizure disorders,7 10–13 with one study of 56 patients reporting cognitive impairment in 28%, ASD in 27%, PVD in 38% and seizure disorders in approximately 10% of patients.7 The presentation of ND, even within families carrying identical NDP mutations, can be extremely variable.14 15 This variability may be due to environmental, genetic or epigenetic factors, and in some cases both partially sighted and blind individuals have been found to carry the same mutation.15

The multifaceted nature of ND, and the presence of dual sensory impairments, has a major impact on both patients and caregivers. Few clinical environments are suitably adapted for children with dual sensory impairments. Similarly, diagnosis and long-term monitoring of ND requires repeat visits to specialist clinicians with knowledge of the best testing methods and interventions. This suggests that a holistic approach to care involving the review of ocular and extraocular symptoms simultaneously would be beneficial to ND patients. Additionally, a multidisciplinary team, including psychologists and social workers, should be included in patient care to help maximise patient outcomes.

Dual Sensory clinics have been suggested to improve the clinical experience of children with sensory impairments. These clinics are designed to accommodate the needs of sensory impaired children while providing access to multiple clinicians in one visit. This reduces the stress and burden associated with numerous, separate medical appointments and optimises communication between professionals. Here, we discuss the challenges experienced by patients with ND, the current clinical approaches for ND management and the potential advantages of Dual Sensory clinics for this complex disease.

Impact of ND

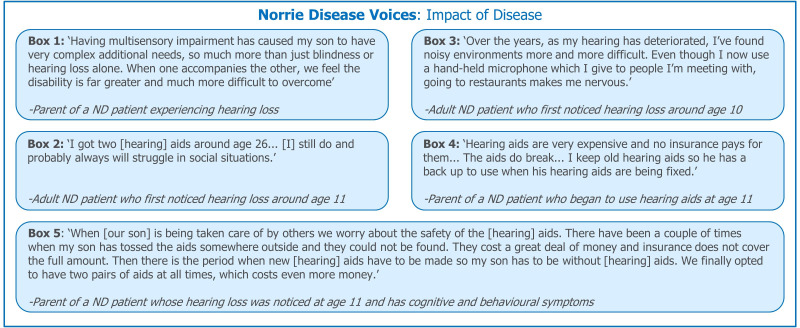

Dual sensory loss is characterised by impairment in two sensory modalities—in ND these are hearing and vision. Sensorineural hearing loss may occur at a young age in patients with ND, highlighting the need for early intervention. Dual sensory loss represents a number of challenges for both the affected patient and their caregivers (figure 2, box 1). These include communication problems, additional educational needs and feelings of isolation. Patients with ND are not thought to experience significant hearing loss before language acquisition7 but developing communication abilities remains a concern.

Figure 2.

Patient and caregiver experiences: impact of dual sensory impairment. The impact of hearing loss in ND affects many aspects of day-to-day life. Quotations were provided by the ND Foundation. ND, Norrie disease.

Physical and psychosocial impact

Visual impairment

Visual impairment represents the most immediate concern in ND, and caregivers must adapt to the needs of a blind child in both family and educational environments. Visually impaired children may have problems establishing and maintaining sleep/wake routines.16 Sleep disorders have been noted in some ND case reports17 and can have serious effects on mood, behaviour, and ability to learn, as well as placing stress on the patient’s family.16

Visual impairment has a significant impact on early child development, with many skills (including sitting, crawling, walking and sound localisation) emerging later than in fully sighted children. Developmental regression has been reported in ND patients,18 while developmental delays and social communication difficulties can affect children with profound visual impairments.19 20

Language skills are often delayed and may develop atypically in visually impaired children. Patients with ND may take longer to both understand and use language and have difficulties with social communication; however, there is limited evidence regarding the impact of sensory loss in ND patients and their ability to build and maintain relationships. Communication with sighted children may be difficult as the ND patient cannot see the non-verbal communication or body language of their peers, which are important contributors to social interactions. Difficulty in communication and play may lead to feelings of isolation and being different to peers, which may contribute to the mental health vulnerabilities recognised in visually impaired children.21

In addition to the impact on development, visual impairment represents a significant barrier to teaching independence skills such as toileting, navigation, cooking and eating. As patients with ND grow older, the cosmetic impact of eye shrinkage may become a concern, and should be monitored by the clinical team.

Dual sensory loss

Developing independence skills as a blind individual often involves using auditory cues.21 22 Progressive hearing loss may further complicate ND patients’ day-to-day life by negating previously developed mechanisms for life without vision. Consequently, blind and hard of hearing people need optimum binaural amplification (coordinated amplification between both ears) to ensure optimal hearing, and localisation of sound (including speech), in every listening environment. Additionally, this amplification may be required at a higher level of hearing than in a sighted person, as mild hearing losses can have a more substantial impact on blind patients. Audiology professionals should be aware of the hearing aid requirements to achieve these amplification needs for their patients with ND.22 23 Similarly, the impacts of hearing loss are exacerbated by blindness. Patients with ND with dual sensory impairment cannot use strategies for improving speech discernment and communication such as sign language through visual means and lip reading.

Despite dual sensory loss, patients with ND exhibit a high degree of independence, with one study reporting that of 32 patients aged ≥18 years, 75% had lived or were living independently7; however, independence remains a concern as hearing loss progresses. For patients with ND with more severe neurological and cognitive features, independence may never be possible, placing a long-term psychosocial and care burden on their families.24

Dual sensory loss can be isolating and may discourage patients from participating in activities they previously enjoyed. A lack of awareness of effective communication methods among the general public may increase these social barriers for patients (figure 2, box 2). Hearing loss may be particularly challenging in social environments such as parties or restaurants which have high levels of background noise (figure 2; box 3).

Progressive hearing loss also increases the psychological impact of ND on patients. Transient depression, directly related to the onset of hearing loss, was reported by the majority of cognitively able ND patients included in a study of clinical histories and genotype data.7 A further case study described how a patient withdrew from society as his hearing deteriorated.25 These findings highlight the psychological impact of hearing loss and the need for patients with ND to receive early, proactive, clinical and emotional support.

Financial impact

Patients with ND have many medical appointments to attend, often with specialists or at clinics that are not local to them, resulting in substantial travel costs. Further costs may be incurred for childcare, or loss of earnings may result from parents of patients with ND having to miss days from work.

Hearing aids may be prescribed to patients with hearing loss, however, the assistive devices provided by health and education services (free of charge in the UK) or medical insurance may not be of sufficient quality or the most appropriate for the patients’ requirements. This can represent a substantial financial burden to families (figure 2, boxes 4 and 5), especially if spare pairs of hearing aids are required to cover loss or repair.

Day-to-day support

It is important that clinicians understand the most appropriate ways to interact with blind and hearing impaired paediatric patients.26 Clinicians may be unaware of the best approach to inform patients of what is happening during their appointment, such as explaining when they are writing notes or preparing equipment. Clinicians may also find it difficult to communicate how a patient should position themselves for a test, and may instead resort to manipulating the patient themselves.26 Parents often assist with the explanation and coordination between clinicians and their child,26 which is important if the clinician is less familiar with the disease.

Current clinical approach

Diagnosis

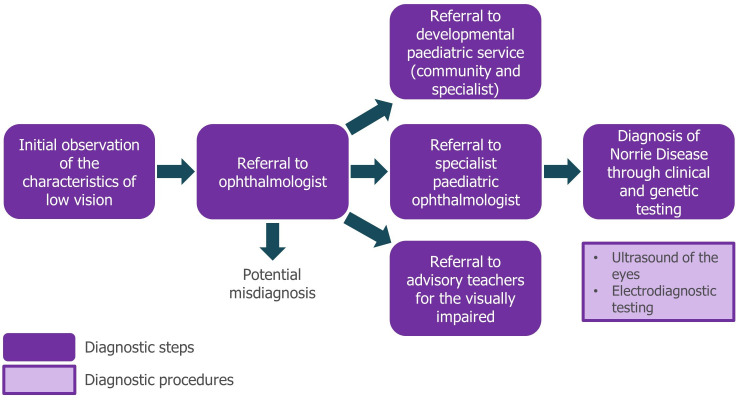

Diagnosis of ND can be a lengthy process (figure 3). Initially, referral to an ophthalmologist is made on observation of nystagmus (rapid, involuntary eye movements), leukocoria (abnormal white reflection from the retina) or a failure of the infant to fix their gaze and follow movement. Due to the rarity of the condition, appropriate referral and diagnosis may be delayed, and misdiagnoses (eg, of glaucoma, congenital cataract or retinoblastoma) can occur. Most patients will eventually be referred to a specialist paediatric ophthalmologist, where they will be fully diagnosed by a combination of ophthalmic examination and investigation including B-mode ultrasound and subsequent genetic testing.

Figure 3.

Norrie disease diagnostic pathway. At present, no guidelines or set routes for diagnosis of ND are available—this pathway represents a typical route for patients as observed in day-to-day clinical practice and is informed by the authoring clinicians. Referral to specialist developmental services should be made as soon as the child is assessed to be blind. ND, Norrie disease.

Though not routine, it is possible to identify ND in utero if the mother is a suspected or known carrier of the disease. Amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling with genetic testing can be used to identify pathogenic NDP variants and determine the sex of a fetus,27 28 while early signs of ocular pathology can be detected using ultrasound.29 30 Alternatively, preimplantation genetic diagnosis can be used to screen embryos derived from in vitro fertilisation to reduce the risk that a child inherits a pathogenic copy of NDP.31

Management

Management of patients with ND requires input from a team of specialists and allied healthcare professionals (figure 1), including hearing, speech and language therapists, an education team (including qualified teachers for the hearing impaired, visually impaired and the deaf-blind), social workers, support groups, psychologists and developmental specialists. This ensures patients with ND receive the support they need to maximise their potential. At the clinician’s discretion, surgical interventions may be offered to paediatric patients with ND in an attempt to preserve light perception (figure 4); however, published case studies demonstrate variable results and the long-term benefit is unclear.6 7 27 32–34 These outcomes must be weighed against the risks associated with surgery (infection, bleeding and glaucoma), which may result in eye pain and the need for enucleation. In two cases, retinal attachment and some visual acuity was preserved following surgical intervention after in utero diagnosis and premature delivery.27 35

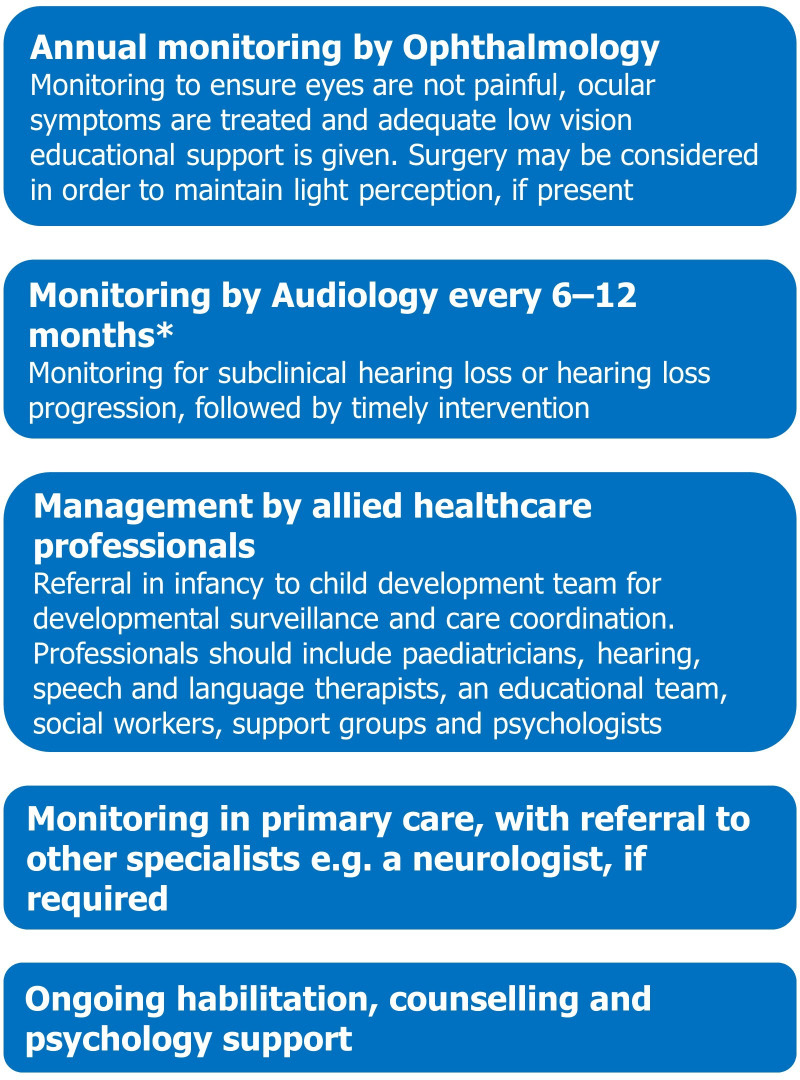

Figure 4.

Management and monitoring of ND patients. *Assessment by audiology for subclinical hearing loss should also be performed as soon as possible after diagnosis, such that any losses can be managed quickly and appropriately. ND, Norrie disease.

As soon as blindness is detected in an infant they should be referred to a specialist developmental paediatrician with the expertise and resources to assess developmental issues as they arise (figure 3). Work with a team of developmental specialists should begin as early as possible to minimise the impact of visual impairment on the patient; the intervention, support and advice of developmental specialists is essential to guide parents in how to assist their child in all areas of development.36

After the detection of hearing impairment, clinicians will consider how best to manage dual sensory loss. Hearing aids are a common intervention for patients with ND2 9 and treating audiology professionals should have a good knowledge of the range of hearing aids available (including those not accessible through the patient’s health service or medical insurance) in order to suggest the most appropriate devices. In particular, clinicians should be aware of the benefits of intervention for even mild hearing losses in blind patients. As hearing loss is progressive in ND, periodic and proactive hearing aid upgrades and the provision of assistive hearing devices may be required to ensure optimal amplification for patients. Clinicians should be familiar with the cochlear implants and vibro-tactile aids available for their patients with ND. Some patients with ND use cochlear implants, and have reported positive impacts on their quality of life.7 25

Monitoring

Routine monitoring of patients with ND is important for identifying the onset of developmental delays and hearing loss (figure 4). Monitoring of the eyes should also be conducted to ensure they are not causing pain and, in patients with no light perception, consideration should be given to the fitting of scleral shells both for improved cosmesis and to promote midfacial growth.

There are no guidelines for monitoring hearing loss in ND—currently, hearing difficulties observed by caregivers typically trigger a referral for assessment. A mouse model of ND shows early changes in the blood vessels of the cochlear (stria vascularis),37 and cochlear dysfunction is believed to occur before hearing loss can be detected using conventional techniques. Careful clinical monitoring for early diagnosis and intervention is necessary (figure 4), as mild, high-frequency hearing loss is often not detected by caregivers. Hearing is extremely important for blind children, and even subclinical losses can have an impact on their developmental trajectory. Early referral to audiology specialists is recommended to allow for monitoring with appropriate behavioural or objective tests such as otoacoustic emissions (sounds generated by the outer hair cells within the inner ear) for the early detection of cochlear dysfunction. Proactive early intervention can help improve speech and language development in children with mild hearing loss.38

Though reduced vestibular function is commonly associated with sensorineural hearing loss,39 it is not known whether the vestibular system is affected by ND. The vestibular system is important for postural stability in the absence of visual cues40 and so its function should be assessed in patients with ND.

Advantages of dual sensory clinics

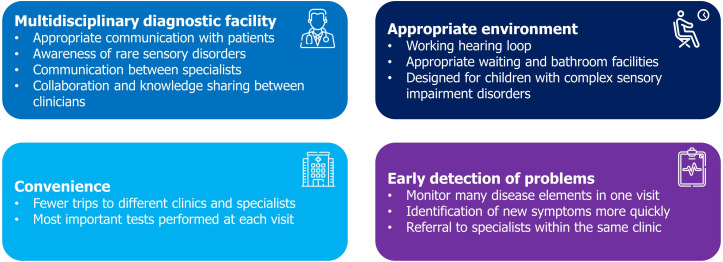

Dual Sensory clinics have been proposed as a way of reducing the impact of complex sensory disorders on patients (figures 5 and 6) and may provide wide ranging benefits to patients and clinicians. Beyond ND, multidisciplinary care is known to be beneficial for patients with a wide range of conditions which feature dual sensory loss, such as Usher syndrome and CHARGE syndrome (abbreviated from the features common in the disorder: Coloboma, Heart defects, Atresia choanae, growth Retardation, Genital abnormalities, Ear abnormalities).

Figure 5.

Advantages of Dual Sensory clinics, informed by published literature.

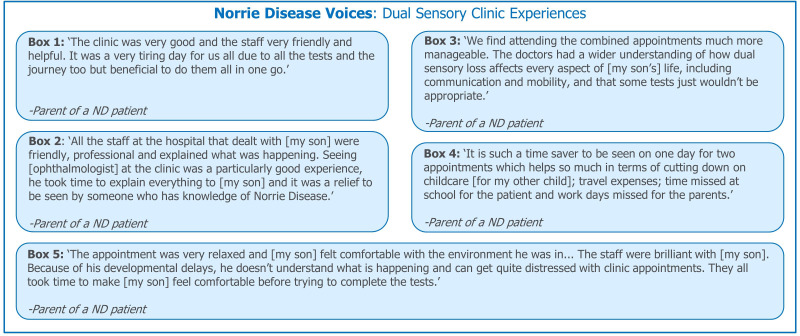

Figure 6.

Patient and caregiver experiences: Dual Sensory clinics. Quotations were provided by the ND Foundation. ND, Norrie disease.

Multidisciplinary diagnostic facility

Within the environment of a Dual Sensory clinic, clinicians are trained in best communication practices for patients with sensory impairments. Appropriate communication, and provision of information in accessible formats (eg, Braille) positively impacts sensory impaired children (figure 6; boxes 2 and 5) and ensures that hospital staff address patients with ND, rather than their caregivers. Effective communication is important during consultations and may involve allowing patients with ND to handle devices (eg, hearing aids, cochlear implant processors) or explaining test results appropriately.26 These appropriate communication techniques allow patients to understand the procedures they may receive, helps them feel included and informed in their care decisions and may reduce stress.26 Communication between clinicians regarding patient needs and care may be improved by bringing them together in a multidisciplinary environment, so improving patient experiences.26

Hearing assessments are often challenging and time consuming in patients with ND, due to their blindness. Some hearing tests use visual cues so require adaption for ND patients and some CHARGE patients. If reliable results are not obtained, a hearing test under general anaesthetic must be considered. Hearing monitoring requires highly experienced staff, who are aware of the needs of patients with ND, ensuring patients’ comfort and understanding of the procedures.

In addition to training and communication, a multidisciplinary environment can promote collaboration and knowledge sharing between clinical experts. A network of such clinics could foster broader collaboration and opportunities for clinicians to discuss patient cases with a wider selection of their peers—this interaction may improve a clinician’s understanding of complex sensory disorders.

Convenience

In the UK, research into the experiences of patients with rare diseases and sensory impairments has revealed that for complex diseases like CHARGE and Usher syndromes, care can be uncoordinated and spread across numerous clinics and hospitals.26 Dual Sensory clinics allow patients to be reviewed by multiple specialist clinicians in one visit, reducing the overall number of hospital visits they need to attend. This may reduce stress, particularly for patients with additional features such as ASD. Reductions in the time spent travelling to and attending appointments can also reduce absences from school for patients, and from the workplace for their parents (figure 6; Box 4).

In the Netherlands, the National Multidisciplinary CHARGE Clinic coordinates care for children and young adults with CHARGE syndrome and provides access to a wide range of clinicians, including a specialist communication and language development team; patients attend every 1–2 years.41

Appropriate environment

Many hospital environments are not designed with sensory impaired paediatric patients in mind; this has been reported by both CHARGE and Usher syndrome patients in the UK.26 Dual Sensory clinics aim to provide comfortable, accessible and functional environments for sensory impaired patients. This includes providing appropriate facilities close to waiting rooms, and ensuring that the waiting room and reception area have working hearing loops.26 Entertainment specifically for sensory impaired children, such as books in Braille and multisensory toys for children of all ages, positively impacts the waiting experience.26 Sensory impaired children may have a preference for, or greater sensitivity to, their sense of touch and smell. A Dual Sensory clinic may be able to consider this in its design, helping to provide an environment better suited to patients’ needs (figure 6, box 2).26

Early detection of health problems

Access to a range of clinicians with specialist disease knowledge increases the chances that health issues are identified more quickly, allowing timely provision of appropriate interventions. Parents have reported that delayed diagnoses contribute to anxiety and stress9; the ease of monitoring health conditions in a Dual Sensory or multidisciplinary clinic may help to alleviate this.

Ongoing challenges

Despite the advantages of offering many different services at one appointment, careful consideration needs to be taken when dealing with very young or developmentally delayed children who may struggle with medical procedures. Clinicians must decide which tests need to be performed most urgently so as not to overburden the patient during their visit. In particular, balance tests and ophthalmic examinations with dilating drops (which sting the eyes and can be very uncomfortable) are unpleasant for the patient, leading to discomfort, tiredness and poor compliance with subsequent tests. Further challenges may be experienced by a minority of patients with ND who have some visual function, as dilating drops may further compromise their access to visual cues for communication.

For many patients with rare, multisensory diseases an ongoing challenge is accessing services tailored to their condition. While the opening of new, specialist clinics represents an advance in care for such children, these are often concentrated in large cities. This small number of clinics and their limited locations can still present issues of travel time and costs for patients with ND and their families.

The transition from paediatric to adult services is another challenge for patients with rare conditions; however, awareness of this issue is increasing. It has been suggested that transition planning should begin from 12 to 14 years of age, should cover a broad range of the patient’s care needs and should involve a coordinating care provider.42 Dual Sensory and multidisciplinary clinics may be of help to facilitate this transition process by ensuring that any changes to care are planned early and are coordinated between teams to avoid disruption to care and distress to the patient.42

Summary

ND is a complex, multifaceted disease of dual sensory impairment that has a significant impact on patients and caregivers. While congenital blindness presents challenges for communication, development and adaptation to the sighted world, development of progressive hearing loss adds to the risk of isolation and psychosocial impact. Early intervention to provide developmental support and identify subclinical hearing loss is necessary to ensure patients with ND can reach their full potential. The complex nature of ND means patients may attend many medical appointments, resulting in absence from school and their caregivers taking time away from work. Additional cost implications may result from the need for specialist equipment and hearing interventions.

Many hospital environments are not suited for children with multiple disabilities and clinicians may be unfamiliar with the best communication practices for interacting with such patients. Provision of Dual Sensory clinics may optimise patient care and experience while streamlining visits to reduce the necessary absence from school, work or social activities. Coordinated multidisciplinary clinics specifically designed to cater to the needs of patients with sensory impairments would be of great benefit to patients with a wide range of complex rare diseases involving vision and hearing loss, including ND.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would especially like to thank the Norrie Disease families and patients who provided quotes about their experience of the disease. The authors thank Aara Patel, PhD, and Valda Pauzuolyte, UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, London, for reviewing and critiquing the manuscript. The authors also acknowledge Wendy Horrobin, The Norrie Disease Foundation, London, for publication coordination and Katherine Massey, PhD and Sarah Jayne Clements, PhD, from Costello Medical, UK, for medical writing and editorial assistance based on the authors’ input and direction. This publication was developed free-of-charge on a pro bono basis by Costello Medical.

Footnotes

Contributors: Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: JCS, RHH, CJK, TS, WP and NO; final approval of the version of the article to be published: JCS, RHH, CJK, TS, WP and NO. Responsibility for opinions, conclusions and interpretation of clinical evidence, and the submitted draft, lies with the authors.

Funding: Third-party writing assistance for this article, provided by Katherine Massey, PhD and Sarah Jayne Clements, PhD, Costello Medical, UK, was provided by Costello Medical free-of-charge on a pro bono basis in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3). JCS is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Great Ormond Street Hospital Biomedical Research Centre and the Great Ormond Street Hospital Children’s Charity and is an NIHR Senior Investigator.

Competing interests: RHH: Received fees for advisory board attendance from Novartis, DORC and Alcon.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data are cited from peer-reviewed literature. No original data are reported.

References

- 1.Sims K. Norrie disease. Available: https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/OC_Exp.php?Lng=EN&Expert=649 [Accessed 06 Dec 2019].

- 2.Sims KB. NDP-Related Retinopathies : Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., GeneReviews((R)). Seattle (WA): University of Washington, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norrie G. Causes of blindness in children. Acta Ophthalmol 1927;5:357–86. 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1927.tb01019.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saini JS, Sharma A, Pillai P, et al. Norries disease. Indian J Ophthalmol 1992;40:24–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sukumaran K. Bilateral Norrie's disease in identical twins. Br J Ophthalmol 1991;75:179–80. 10.1136/bjo.75.3.179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang X-Y, Jiang W-Y, Chen L-M, et al. A novel Norrie disease pseudoglioma gene mutation, c.-1_2delAAT, responsible for Norrie disease in a Chinese family. Int J Ophthalmol 2013;6:739–43. 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2013.06.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith SE, Mullen TE, Graham D, et al. Norrie disease: extraocular clinical manifestations in 56 patients. Am J Med Genet A 2012;158A:1909–17. 10.1002/ajmg.a.35469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halpin C, Owen G, Gutiérrez-Espeleta GA, et al. Audiologic features of Norrie disease. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2005;114:533–8. 10.1177/000348940511400707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halpin C, Sims K. Twenty years of audiology in a patient with Norrie disease. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2008;72:1705–10. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blodi FC, Hunter WS. Norrie's disease in North America. Doc Ophthalmol 1969;26:434–50. 10.1007/BF00944002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michaelides M, Luthert PJ, Cooling R, et al. Norrie disease and peripheral venous insufficiency. Br J Ophthalmol 2004;88:1475. 10.1136/bjo.2004.042556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okumura A, Arai E, Kitamura Y, et al. Epilepsy phenotypes in siblings with Norrie disease. Brain Dev 2015;37:978–82. 10.1016/j.braindev.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamada K, Limprasert P, Ratanasukon M, et al. Two Thai families with Norrie disease (nd): association of two novel missense mutations with severe Nd phenotype, seizures, and a manifesting carrier. Am J Med Genet 2001;100:52–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen RC, Russell SR, Streb LM, et al. Phenotypic heterogeneity associated with a novel mutation (Gly112Glu) in the Norrie disease protein. Eye 2006;20:234–41. 10.1038/sj.eye.6701840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaremba J, Feil S, Juszko J, et al. Intrafamilial variability of the ocular phenotype in a Polish family with a missense mutation (A63D) in the Norrie disease gene. Ophthalmic Genet 1998;19:157–64. 10.1076/opge.19.3.157.2184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stores G, Ramchandani P. Sleep disorders in visually impaired children. Dev Med Child Neurol 1999;41:348–52. 10.1017/s0012162299000766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vossler DG, Wyler AR, Wilkus RJ, et al. Cataplexy and monoamine oxidase deficiency in Norrie disease. Neurology 1996;46:1258–61. 10.1212/wnl.46.5.1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harendra de Silva DG, de Silva DB. Norrie's disease in an Asian family. Br J Ophthalmol 1988;72:62–4. 10.1136/bjo.72.1.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dale N, Sonksen P, outcome D. Developmental outcome, including setback, in young children with severe visual impairment. Dev Med Child Neurol 2002;44:613–22. 10.1017/s0012162201002651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dale NJ, Tadić V, Sonksen P. Social communicative variation in 1-3-year-olds with severe visual impairment. Child Care Health Dev 2014;40:158–64. 10.1111/cch.12065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris J, Lord C. Mental health of children with vision impairment at 11 years of age. Dev Med Child Neurol 2016;58:774–9. 10.1111/dmcn.13032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brabyn JA, Schneck ME, Haegerstrom-Portnoy G, et al. Dual sensory loss: overview of problems, visual assessment, and rehabilitation. Trends Amplif 2007;11:219–26. 10.1177/1084713807307410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simon HJ, Levitt H. Effect of dual sensory loss on auditory localization: implications for intervention. Trends Amplif 2007;11:259–72. 10.1177/1084713807308209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bleeker-Wagemakers EM, Zweije-Hofman I, Gal A. Norrie disease as part of a complex syndrome explained by a submicroscopic deletion of the X chromosome. Ophthalmic Paediatr Genet 1988;9:137–42. 10.3109/13816818809031489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacques D, Dubois T, Zdanowicz N, et al. Cochlear implants and psychiatric assessments: a Norrie disease case report. Psychiatr Danub 2017;29:259–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellis L, Keenan L, Hodges. L. The experiences of people with rare syndromes and sensory impairments in hospitals and clinics, 2015. Available: https://www.sense.org.uk/umbraco/surface/download/download?filepath=/media/1294/research-the-experiences-of-people-with-rare-syndromes-and-sensory-impairments-in-hospitals-and-clinics-report.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2019].

- 27.Chow CC, Kiernan DF, Chau FY, et al. Laser photocoagulation at birth prevents blindness in Norrie's disease diagnosed using amniocentesis. Ophthalmology 2010;117:2402–6. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghosh M, Sharma S, Shastri S, et al. Norrie disease: first mutation report and prenatal diagnosis in an Indian family. Indian J Pediatr 2012;79:1529–31. 10.1007/s12098-012-0788-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Redmond RM, Vaughan JI, Jay M, et al. In-Utero diagnosis of Norrie disease by ultrasonography. Ophthalmic Paediatr Genet 1993;14:1–3. 10.3109/13816819309087615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu LH, Chen L-H, Xie H, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of a case of Norrie disease with late development of bilateral ocular malformation. Fetal Pediatr Pathol 2017;36:240–5. 10.1080/15513815.2017.1307474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yahalom C, Macarov M, Lazer-Derbeko G, et al. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis as a strategy to prevent having a child born with an heritable eye disease. Ophthalmic Genet 2018;39:450–6. 10.1080/13816810.2018.1474368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Callaway NF, Berrocal AM. Wnt-Spectrum vitreoretinopathy masquerading as congenital toxoplasmosis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina 2018;49:446–50. 10.3928/23258160-20180601-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sims KB, Irvine AR, Good WV. Norrie disease in a family with a manifesting female carrier. Arch Ophthalmol 1997;115:517–9. 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150519012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walsh MK, Drenser KA, Capone A, et al. Early vitrectomy effective for Norrie disease. Arch Ophthalmol 2010;128:456–60. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sisk RA, Hufnagel RB, Bandi S, et al. Planned preterm delivery and treatment of retinal neovascularization in Norrie disease. Ophthalmology 2014;121:1312–3. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dale NJ, Sakkalou E, O'Reilly MA, et al. Home-based early intervention in infants and young children with visual impairment using the developmental Journal: longitudinal cohort study. Dev Med Child Neurol 2019;61:697–709. 10.1111/dmcn.14081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rehm HL, Zhang D-S, Brown MC, et al. Vascular defects and sensorineural deafness in a mouse model of Norrie disease. J Neurosci 2002;22:4286–92. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04286.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walker EA, Holte L, McCreery RW, et al. The influence of hearing aid use on outcomes of children with mild hearing loss. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2015;58:1611–25. 10.1044/2015_JSLHR-H-15-0043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tribukait A, Brantberg K, Bergenius J. Function of semicircular canals, utricles and saccules in deaf children. Acta Otolaryngol 2004;124:41–8. 10.1080/00016480310002113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giagazoglou P, Amiridis IG, Zafeiridis A, et al. Static balance control and lower limb strength in blind and sighted women. Eur J Appl Physiol 2009;107:571–9. 10.1007/s00421-009-1163-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.University of Groningen The National Multidisciplinary CHARGE clinic. Available: https://www.rug.nl/research/genetics/research/chargesyndrome/charge-clinic?lang=en [Accessed 03 Sep 2020].

- 42.Dijk DR, Bocca G, van Ravenswaaij-Arts CM. Growth in charge syndrome: optimizing care with a multidisciplinary approach. J Multidiscip Healthc 2019;12:607–20. 10.2147/JMDH.S175713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.