Dear Editor,

Swine acute diarrhoea syndrome coronavirus (SADS-CoV) is a novel swine enteric coronavirus belonged to the Coronaviridae family, Alphacoronavirus genus (Zhou P et al. 2018). The clinical signs of SADS include acute diarrhoea and vomiting, which was similar with the infection of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) and porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) (Wang et al. 2019). The first outbreak of SADS, reported at multiple sites in Guangdong Province, China, led to the death of ten thousands of piglets (Zhou P et al. 2018). Subsequently, retrospective study demonstrated that SADS-CoV had emerged in China since August 2016 (Zhou L et al. 2018). After the devastating outbreak of SADS in January 2017, the re-emergence of SADS-CoV was reported in Fujian and Guangdong provinces in 2018 and 2019, respectively (Li et al. 2018; Zhou et al. 2019).

Genome sequence analysis revealed that SADS-CoV is closely related to bat coronavirus HKU2 (Gong et al. 2017; Pan et al. 2017). The phylogenetic and haplotype network analyses showed that different SADS-CoVs occurred in Guangdong probably originated from their reservoir hosts independently (Zhou P et al. 2018). The spike (S) gene of SADS-CoV detected in Fujian shared more similarity with bat SADS-related coronaviruses (SADSr-CoVs) than other SADS-CoV strains, and more similar insertion/deletion patterns between Fujian strain and bat SADSr-CoVs were observed in genome-scale, suggesting that Fujian strain might originate from bats directly (Li et al. 2018). Our previous studies have reported that SADSr-CoVs were detected in four species of Rhinolophus bats (R. affinis, R. sinicus, R. rex, and R. pusillus) in several provinces of Southern China (Zhou P et al. 2018; Fan et al. 2019). Recently, we have identified several SADSr-CoVs in R. affinis which are closely related to the epidemic strains in pigs. These newly identified SADSr-CoVs share higher similarity (> 99%) with SADS-CoV in S gene than those previously reported (unpublished data). These results provide further evidences that SADS-CoV remains a serious threat to swine and closely related viruses are still circulating in these bat populations. Given the frequent contacts among bat, swine and human, it’s critically important to assess spillover potentials of SADS-CoV to human and other animals. Before that, a research group has reported a broad cell tropism of SADS-CoV, highlighting its potential cross-species infection risk (Yang et al. 2019). In order to provide more information of SADS-CoV cell tropism to assess spillover potentials, we performed an infectivity assays with another isolate of SADS-CoV in more cell lines from reservoir host (bat), susceptible host (swine) and potential hosts (human and other animals).

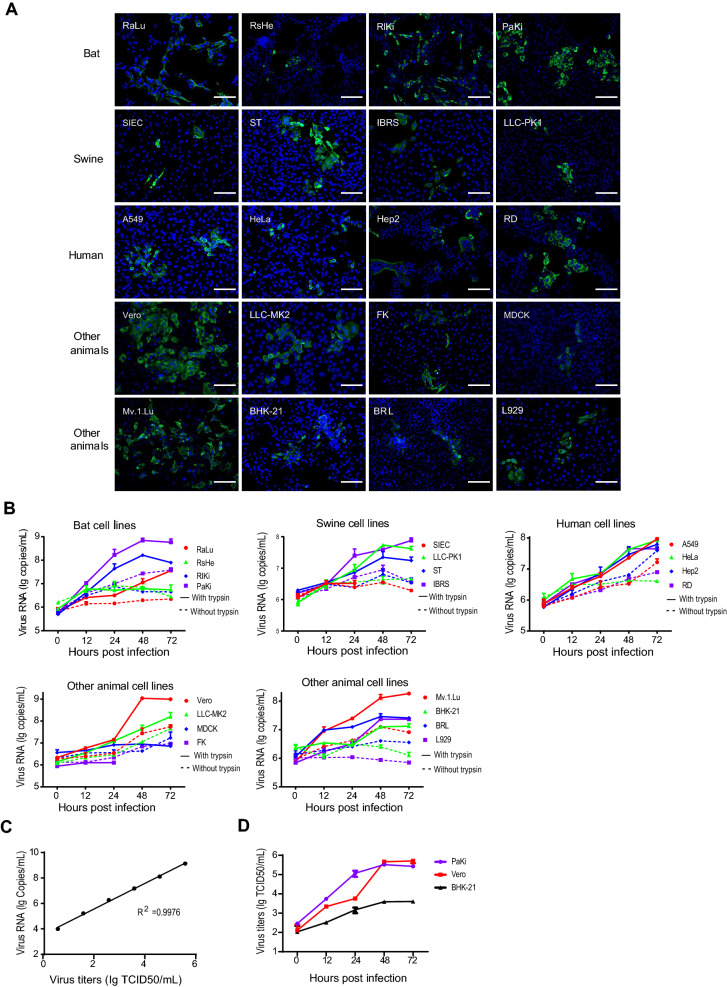

A total of 20 (Table 1) primary or transformed cell lines derived from different host species, including human (A549, HeLa, Hep2, RD), swine (SIEC, ST, IBRS, LLC-PK1), bat (RaLu, RsHe, RlKi, PaKi), monkey (Vero, LLC-MK2), dog (MDCK), cat (FK), rat (BRL), mouse (L929), hamster (BHK-21) and mink (Mv.1.Lu), were inoculated with SADS-CoV isolate CN/GDWT/2017 (GenBank accession number MG557844) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 in 24-well plates and maintained in serum-free medium with or without of 2 µg/mL trypsin. Cell susceptibility was determined by immunofluorescence assay (IFA) in trypsin-treated cells targeting nucleocapsid (N) protein of SADS-CoV. Briefly, cells were washed at 24 h post-infection (hpi), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature and then permeabilized with 0.1% TritonX-100. Cells were then incubated with rabbit anti-SADSr-CoV N polyclonal antibody followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (ProteinTech, China) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Zhou P et al. 2018). Fluorescent images were examined under an AMF4300 EVOS FL cell Imaging System (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). SADS-CoV infection was detected in all 20 tested cell lines derived from bat, swine, human, monkey, cat, dog, mink, rat and mouse through IFA (Fig. 1A). The higher expression of SADS-CoV N protein was observed in bat (RaLu, RlKi and PaKi), swine (ST), human (A549, RD), monkey (Vero, LLC-MK2) and mink (Mv.1.Lu) cells in serum-free medium supplemented with trypsin (Table 1). Significant cytopathic effects (CPEs) were observed in infected IBRS, HeLa and Vero cells in the presence of trypsin after 72 h, and these were not reported in the previous study except for Vero (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Table 1.

Cell lines derived from different hosts were tested for the susceptibility to SADS-CoV.

| Host | Cell line | Origin of cell line | Expression of N protein at 24 hpia | Cytopathic effect at 72hpib |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bat | RaLu# | Rhinolophus. affinis lung | ++++ | N |

| RsHe | Rhinolophus. sinicus heart | + | N | |

| RlKi | Rousettus leschenaultia kidney | ++++ | N | |

| PaKi | Pteropus alecto kidney | ++++ | N | |

| Swine | SIEC | Sus scrofa intestine | + | N/D |

| ST* | S. scrofa testicle | ++++ | N | |

| IBRS | S. scrofa kidney | ++ | P | |

| LLC-PK1* | S. scrofa kidney | + | N | |

| Human | A549* | Homo sapiens lung | ++ | N |

| HeLa* | H. sapiens cervix | + | P | |

| Hep2 | H. sapiens larynx | ++ | N | |

| RD | H. sapiens embryonic | ++++ | N | |

| Monkey | Vero* | Chlorocebus aethiops kidney | ++++ | P |

| LLC-MK2 | Macaca mulatta kidney | +++ | N | |

| Cat | FK | Felinae kidney | ++ | N/D |

| Dog | MDCK* | Canis familiaris kidney | + | N |

| Mink | Mv.1.Lu | Mustla vison lung | ++++ | N |

| Hamster | BHK-21* | Mesocricetus auratus kidney | ++ | N |

| Rat | BRL* | Rattus norvegicus liver | + | N |

| Mouse | L929 | Mus musculus lung | + | N |

The susceptibility of SADS-CoV in trypsin-treated cells was determined by expression of SADS-CoV N protein and Cytopathic effect.

aExpression efficiency of N protein is defined by green fluorescence positive cell ratio; + , 1%–5%; ++ , > 5%–10%; +++ , > 10%–25%; ++++ , > 25%.

bP and N are defined as positive and negative, respectively. N/D, Not detected due to their sensitivity to trypsin.

*Cell lines have been tested for the susceptibility to SADS-CoV by Yang et al. (2019).

#The primary cell line established in our laboratory.

Fig. 1.

The cell infection results of SADS-CoV determined by IFA, qRT-PCR and TCID50 assays. A The expression of N protein at 24 hpi in SADS-CoV-infected cells assessed by IFA. Scale bars, 100 μm. B The amounts of supernatant viral RNA in SADS-CoV-infected cells assessed in duplicate by qRT-PCR. Cell lines were infected in duplicate with virus at an MOI = 1. Supernatant was harvested at 0, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hpi. The infection of SIEC and FK was not tested after 24 hpi due to their sensitivity to trypsin. C Linear correlation between viral titers and RNA copies. D The replication efficiencies of SADS-CoV in PaKi, Vero and BHK-21 were determined by TCID50 assays.

Viral replication efficiency in different cell lines was determined by quantitative RT-PCR, as well as TCID50 assays in three representative cell lines. Briefly, Viral RNA was extracted from supernatant at different time points using the QIAamp 96 Virus QIAcube HT Kit (Qiagen, Germany). A real-time one-step quantitative RT-PCR assay was used for detection of SADS-CoV RdRp gene, using the HiScript One-Step qRT-PCR SYBR Green kit (Vazyme, China) as described previously (Luo et al. 2018). Specific primers for the RdRp gene of SADS-CoV (forward: 5´-GCGATGAGATGGTCACTAAAGG-3´) and reverse: 5´-GGAATACCCATACCTGGCATAAC-3´) were designed according to reference sequence (MG557844). The mean viral loads in the tested cells increased at different levels (Fig. 1B). The mean viral loads of SADS-CoV increased by approximately 2 logs in the presence of trypsin in two tested bat cell lines (RlKi and PaKi), four tested human cell lines (A549, HeLa, Hep2 and RD), two tested monkey cell lines (Vero and LLC-MK2) and mink cell line (Mv.1.Lu). While the mean viral loads increased slightly in the RsHe, SIEC, MDCK and FK cells in the presence or absence of trypsin (Fig. 1B). The viral load of mouse cell lines (L929) had more than 1 log increase in the presence of trypsin, but no increase in absence of trypsin. In addition, serial tenfold dilutions of virus (TCID50 = 3.89 × 105/mL) were calibrated with viral RNA copies. We demonstrated that there was an excellent linear correlation (R2 = 0.9976) between the infectious virions and RNA copies (Fig. 1C). We also titrated the infectious virions secreted from three representative trypsin-treated cell lines in Vero cells and observed more efficient SADS-CoV replication in PaKi and Vero cells than on BHK-21 cells. Such trend of viral replication determined by TCID50 assays were consistent with that obtained by qRT-PCR (Fig. 1D).

In summary, all 20 cell lines derived from various tissues of bat, swine, human and other animal species are susceptible to SADS-CoV, defined by N expression, the appearance of CPE, and efficient viral replication. These results indicate that SADS-CoV has a broad cell tropism and highlighted the potential of cross-species, which is consistent with the previous study (Yang et al. 2019). In the study by Yang et al. (2019), 21 of the 24 cell lines showed significant susceptibility to SADS-CoV infection. The three cell lines could not be infected by SADS-CoV, including BFK, a fetal kidney cell line from Myotis daubentonii, RAW264.7, a monocyte/macrophage cell line from mice, and MDCK. There are 8 cell lines were tested by both our groups (Table 1) and only MDCK showed inconsistent results, probably because a higher MOI was provided to the cells (MOI = 1 while Yang et al. used an MOI = 0.01). In our study, we tested more bat derived cells including two insectivore bats (R. affinis and R. sinicus) and two frugivore bats (R. leschenaultia and P. alecto). SADS-CoV showed higher replication in cells from R. leschenaultia and P. alecto than R. affinis and R. sinicus which are regarded as reservoir hosts of SADS-CoV, indicating that SADS-CoV could infect bat species from different family in nature. In addition, we tested two cells (FK and Mv.1.Lu) derived from two new hosts species (feline and mink), and we observed a limited virus propagation in FK but efficient replication in Mv.1.Lu. These results suggest that SADS-CoV might have a broader host range than previously recognized. Most strikingly, we found that SADS-CoV showed higher replication efficiency in four tested human cell lines than four tested swine cell lines, highlighting the risk of cross-species transmission to human. Both the human upper airway (Hep2) and lower airway (A549) cell lines support the growth of this virus in presence or absence of trypsin, raising the possibility of airborne transmission among humans. In consistent with previous study, SADS-CoV replication was limited in the absence of trypsin in serum-free medium. Exogenous trypsin and specific endogenous protease located at the cell surface may play important role in activating the fusion of SADS-CoV S protein for efficient cell entry.

Due to high mutation rates and unique recombination mechanism, some coronaviruses can cross species barriers and adapt to new hosts. Newly emerging coronaviruses pose a potential threat to human health attributing to the fact that many human CoVs infections have been derived from animal hosts. SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, which seem to originate from bat and were transmitted to human by intermediate animals such as civet or camel (Wang and Anderson 2019; Zhou et al. 2020). SADS-CoV is probably the first bat-derived coronavirus that is found to infect pig directly in recent years. Pigs are regarded as mixing vessels and intermediate hosts of several viruses, such as avian influenza A viruses and Nipah virus (Sun et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2018). Given that a novel swine enteric coronavirus (SeCoV) is generated by the recombination of porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus and PEDV, recombination between SADS-CoV and other swine coronaviruses cannot be excluded (Akimkin et al. 2016; Boniotti et al. 2016). Our study suggests that SADS-CoV has a wide range of cell tropism and can replicate in most of the tested cells. To our knowledge, this range of cell tropism in vitro is broader than any known coronaviruses tested for cell line susceptibility, including SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, which imply its high risk of cross-species ability. In view of severe diseases caused by interspecies transmission of SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV, intensive surveillances are needed to prevent the future spillover of SADS-CoVs and SADSr-CoVs.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Jing-Yun Ma (College of Animal Science, South China Agricultural University) for providing SADS-CoV isolate CN/GDWT/2017. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31830096).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human and animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Yun Luo and Ying Chen authors contributed equally to this work

References

- Akimkin V, Beer M, Blome S, Hanke D, Hoper D, Jenckel M, Pohlmann A. New chimeric porcine coronavirus in swine feces, Germany, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1314–1315. doi: 10.3201/eid2207.160179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boniotti MB, Papetti A, Lavazza A, Alborali G, Sozzi E, Chiapponi C, Faccini S, Bonilauri P, Cordioli P, Marthaler D. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus and discovery of a recombinant swine enteric coronavirus, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:83–87. doi: 10.3201/eid2201.150544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Zhao K, Shi ZL, Zhou P. Bat coronaviruses in China. Viruses. 2019;11:210. doi: 10.3390/v11030210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong L, Li J, Zhou Q, Xu Z, Chen L, Zhang Y, Xue C, Wen Z, Cao Y. A new bat-HKU2-like coronavirus in swine, China, 2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:1607–1609. doi: 10.3201/eid2309.170915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K, Li H, Bi Z, Gu J, Gong W, Luo S, Zhang F, Song D, Ye Y, Tang Y. Complete genome sequence of a novel swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus, CH/FJWT/2018, isolated in Fujian, China, in 2018. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2018;7:e01259–e11218. doi: 10.1128/MRA.01259-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Li B, Jiang RD, Hu BJ, Luo DS, Zhu GJ, Hu B, Liu HZ, Zhang YZ, Yang XL, Shi ZL. Longitudinal surveillance of betacoronaviruses in fruit bats in Yunnan Province, China during 2009–2016. Virol Sin. 2018;33:87–95. doi: 10.1007/s12250-018-0017-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Tian X, Qin P, Wang B, Zhao P, Yang YL, Wang L, Wang D, Song Y, Zhang X, Huang YW. Discovery of a novel swine enteric alphacoronavirus (SeACoV) in southern China. Vet Microbiol. 2017;211:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B, Jia L, Liang B, Chen Q, Liu D. Phylogeography, transmission, and viral proteins of nipah virus. Virol Sin. 2018;33:385–393. doi: 10.1007/s12250-018-0050-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LF, Anderson DE. Viruses in bats and potential spillover to animals and humans. Curr Opin Virol. 2019;34:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Su S, Bi Y, Wong G, Gao GF. Bat-origin coronaviruses expand their host range to pigs. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26:466–470. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Vlasova AN, Kenney SP, Saif LJ. Emerging and re-emerging coronaviruses in pigs. Curr Opin Virol. 2019;34:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YL, Qin P, Wang B, Liu Y, Xu GH, Peng L, Zhou J, Zhu SJ, Huang YW. broad cross-species infection of cultured cells by bat HKU2-related swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus and identification of its replication in murine dendritic cells in vivo highlight its potential for diverse interspecies transmission. J Virol. 2019;93:e01448–e11419. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01448-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Sun Y, Lan T, Wu RT, Chen JW, Wu ZX, Xie QM, Zhang XB, Ma JY. Retrospective detection and phylogenetic analysis of swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus in pigs in southern China. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2018;66:687–695. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P, Fan H, Lan T, Yang XL, Shi WF, Zhang W, Zhu Y, Zhang YW, Xie QM, Mani S, Zheng XS, Li B, Li JM, Guo H, Pei GQ, An XP, Chen JW, Zhou L, Mai KJ, Wu ZX, Li D, Anderson DE, Zhang LB, Li SY, Mi ZQ, He TT, Cong F, Guo PJ, Huang R, Luo Y, Liu XL, Chen J, Huang Y, Sun Q, Zhang XL, Wang YY, Xing SZ, Chen YS, Sun Y, Li J, Daszak P, Wang LF, Shi ZL, Tong YG, Ma JY. Fatal swine acute diarrhoea syndrome caused by an HKU2-related coronavirus of bat origin. Nature. 2018;556:255–258. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0010-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Li QN, Su JN, Chen GH, Wu ZX, Luo Y, Wu RT, Sun Y, Lan T, Ma JY. The re-emerging of SADS-CoV infection in pig herds in Southern China. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2019;00:1–4. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si HR, Zhu Y, Li B, Huang CL, Chen HD, Chen J, Luo Y, Guo H, Jiang RD, Liu MQ, Chen Y, Shen XR, Wang X, Zheng XS, Zhao K, Chen QJ, Deng F, Liu LL, Yan B, Zhan FX, Wang YY, Xiao GF, Shi ZL. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.