Abstract

Background:

Symptoms of depressed mood and anxiety have been associated with immune dysregulation and atopic disorders, however it is unclear whether this relationship spans other forms of psychopathology. The objective of this study was to use a large, population-based sample to examine the association between several common psychiatric conditions and two atopic disorders: seasonal allergies and asthma. This study also examined whether comorbidity between psychiatric disorders confounded the relationship between atopy and each psychiatric disorder.

Methods:

Data come from the Comprehensive Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys, a nationally-representative sample of US adults (N=10,309). Lifetime history of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), Panic Disorder (PD), and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) was assessed using the Composite International Diagnostic Inventory. History of seasonal allergies and asthma were assessed by self-report. Weighted logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between allergies and asthma and psychopathology. Psychiatric comorbidities were also examined as potential confounders.

Results:

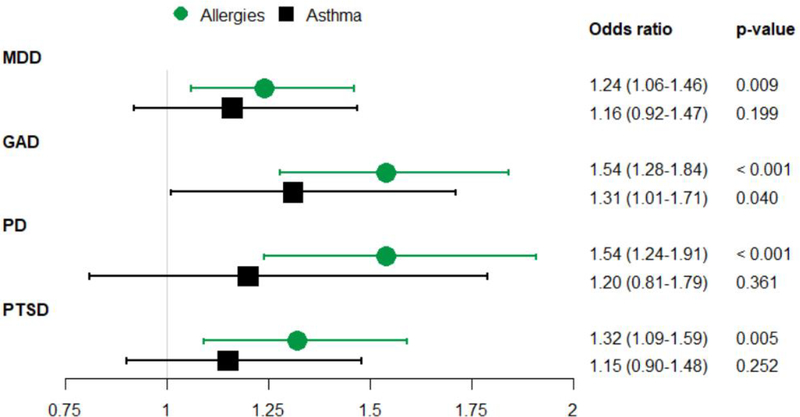

Approximately 36.6% had a history of allergies and 11.5% a history of asthma. Seasonal allergies were positively associated with odds of MDD (Odds ratio (OR): 1.24, 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.06–1.46), GAD (OR: 1.54 (1.28–1.84)), PD (OR: 1.54 (1.24–1.91)), and PTSD (OR: 1.32 (1.09–1.59)). Asthma was not significantly associated with any psychiatric disorder. All significant associations persisted after adjustment for psychiatric comorbidities.

Limitations:

Limitations include self-reporting of atopic disorder status and of all disorder ages of onset.

Conclusions:

This study confirms the association between MDD and PD and seasonal allergies, and extends this relationship to GAD and PTSD.

Keywords: Atopic, allergies, depression, anxiety, panic, PTSD

Introduction

The term atopy refers to a propensity to develop an immunologic sensitivity to benign antigens typically tolerated by non-atopic individuals (1). Atopic disorders are a family of disorders including allergic rhinitis, asthma, and some forms of eczema. Atopic disorders are highly heritable (2, 3) and highly comorbid with each other (4, 5), suggesting they may share or have overlapping genetic susceptibility (2, 6, 7). In susceptible individuals, exposures that trigger an atopic response may result in elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP) (8–12). Elevated levels of inflammatory markers have been correlated with a range of mental health outcomes (13–16).

Several studies have also suggested a relationship between common psychiatric disorders and atopic conditions. Large community-based studies have shown that major depressive disorder (MDD) is associated with both allergies (17–20) and asthma (21–23). A link between panic disorder (PD) and asthma has been widely replicated (23, 24), and this relationship appears to be bidirectional (25); only a handful of studies have examined the link between PD and allergies, but these also suggest a positive association (26, 27). Few studies have examined the relationship between generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and atopic disorders, and results are mixed (23, 26, 28, 29). Finally, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been associated with history of asthma (23, 30, 31), however it is likely that this relationship is at least partially explained by trauma associated with asthma attacks (32). There is little known about the relationship between PTSD and seasonal allergies, although one paper has reported an association (33). Finally, experimental studies in animals have demonstrated that allergen exposure in sensitized animals can lead to increases in anxiety-like behavior and reductions in social behavior.(34)

In sum, although multiple studies suggest a relationship between atopic disorders and common psychiatric disorders, the strength of this evidence varies across conditions. In some cases, evidence is limited to small, treatment-seeking clinical samples that may differ from the general population on factors such as disease severity and access to medical care (35, 36). Existing reports often examine only one atopic or psychiatric disorder in isolation, and thus it is unresolved whether these hypothesized relationships are consistent across a broad range of psychopathology or across multiple atopic conditions. Measurement of psychopathology also varies, limiting the ability to compare and evaluate disparate findings. Finally, because psychiatric conditions are highly comorbid with each other,(37) it is possible that if one psychiatric disorder were associated with atopy it could confound the relationship between other disorders and atopy, an issue that is rarely addressed in existing literature.

The objective of this study was to examine the relationships between two common atopic disorders, seasonal allergies and asthma, and several common psychiatric disorders using a large community-based sample. We hypothesized that both atopic disorders would show an association with a broad range of psychiatric disorders. We also hypothesized that earlier age of the onset for the atopic disorders would be more strongly associated with psychopathology than atopic disorders that onset later in life.

Methods

Sample

Data come from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES) (38). The CPES consists of three nationally-representative household surveys of US adults: the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R), the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS), and the National Survey of American Life (NSAL). All three studies were conducted from 2001 – 2003. All surveys of the CPES employed the Composite International Diagnostic Inventory (CIDI) to assess psychopathology as described below. Additional details of the CPES methodology are described elsewhere (39).

The analytic sample for this paper is limited to CPES respondents who were asked about lifetime histories of allergies and asthma (N=10,341 from the NLAAS and the long form of the NCS-R only). The sample was further limited to respondents with complete data on the psychiatric disorders of interest (MDD, GAD, PD, PTSD), history of atopic disorders, and model covariates (N=10,309). Of the participants who were excluded for missing data, eight were missing data on lifetime histories of allergies and asthma, and 24 were missing data on health insurance status.

For the analysis examining age-of-onset of atopic disorders in relation to psychopathology, the sample was restricted to respondents with a positive history of the atopic disorder in question and who provided valid data on their age at onset for the condition. Of the 3,512 individuals with a history of seasonal allergies, 3,290 (93.7%) provided a valid age at onset. Of the 1,202 individuals with a history of asthma, 1,137 (94.6%) provided a valid age at onset.

The institutional review boards at the University of Michigan, Harvard University, Cambridge Health Alliance, and the University of Washington approved the component surveys of the CPES (40). This analysis used only de-identified publicly available data and was exempt from human subjects regulation.

Measures

History of psychopathology

Lifetime histories of MDD, GAD, PD, and PTSD were assessed using the DSM-IV version of the World Mental Health CIDI. This instrument consists of structured interviews based on the DSM-IV criteria for each disorder assessed (41), and has been shown to perform well when compared to a clinician-administered semi-structured interview (42). Respondents were considered to have a lifetime history of a disorder if they reported at least one period in their life during which they met the DSM-IV criteria for the disorder (43). These disorders were selected because (a) they were assessed in both the NCS-R and NLAAS, (b) they were relatively common (had a lifetime prevalence >5%) (c) they had support from prior literature. Only a limited number of disorders could be selected due to the need to balance the exploratory nature of our research question with the analytic need to account for multiple comparisons.

History of atopic disorders

Lifetime histories of seasonal allergies and asthma were assessed by self-report. For allergies, respondents were asked “Have you ever had seasonal allergies like hay fever?”. For asthma, respondents were asked “Did a doctor or other health professional ever tell you that you had asthma?” Although the accuracy of self-report assessment of atopic conditions like these may vary as a function of disease severity, previous studies of depression using clinician-verified asthma and blood measures have produced similar results to studies using self-reported measures (22, 44–46). Information about the age at onset of allergies and asthma was also assessed by self-report. Age of onset was categorized as childhood-onset (ages 0–12), teen-onset (ages 13–18), or adult-onset (age 19+). We chose to categorize this variable because our goal is to explore whether there is heterogeneity within the atopic disorder-mental health relationship as a function of the life stage at which the atopic disorder developed (47, 48); as a result, modeling age at onset as a continuous variable would not be appropriate.

Other covariates

Age at time of interview (in years), gender, race, household income-to-poverty ratio (IPR), and health insurance coverage status were assessed by self-report. Initial covariate fit analyses showed that the relationship between age and psychopathology was non-linear. As a result, this variable was categorized as 18–29, 30–44, 45–64, and 65+. Race was categorized as “black”, “Hispanic”, “other”, or “white” based on respondent self-report. IPR is the ratio of annual household income to the poverty threshold for the respondent’s family size as determined by the US Census Bureau (49). This variable was categorized into three levels: Income at or below the poverty limit, income two to three times the poverty limit, and income four or more times the poverty limit. Health insurance coverage was based on questions about the respondent’s receipt of medical coverage through employer-provided health insurance, privately-purchased insurance, military medical coverage, Medicare, Medicaid, or other assistance programs or coverage, with respondents reporting having one or more of these classified as having health coverage, and individuals reporting none of these classified as not covered.

Analysis

Multivariable logistic regression models were used to assess the association between allergies and asthma and each of the four psychiatric outcomes. Each exposure was assessed in relation to four outcomes (MDD, PD, PTSD, and GAD); a Bonferroni-adjusted significance cutoff of 0.0125 was calculated to account for multiple testing. Initial models were adjusted for age, gender, race, IPR and health insurance coverage. Following this, models were additionally adjusted for comorbid disorders (e.g., models of allergies predicting MDD were adjusted separately for PD, PTSD and GAD), to examine whether the relationships identified in the main model were confounded by psychiatric comorbidity. Controlling separately for each comorbidity increased the number of models from four to sixteen, however we retained our original Bonferroni-adjusted significance cutoff of 0.0125 because only four exposure/outcome associations were being tested. Finally, logistic models were fit to examine whether the age-at-onset of the atopic disorder was associated with odds of the psychiatric disorder.

We then conducted a series of sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of our findings. First, we expanded the outcome of panic from PD (approximately 4.1% of the sample had PD) to lifetime history of a panic attack (approximately 23.4% of the sample had experienced a panic attack), to assess whether the lack of association with asthma in the initial analysis was due to the small overall number of PD cases. Next, we examined whether the relationship between lifetime psychopathology and lifetime history of seasonal allergies replicated when using past-year history of each exposure and outcome; this analysis was conducted for allergies only, as history of asthma was only assessed over the lifetime, not in the past year. Finally, we examined whether including respondents from the NSAL in the analytic sample for asthma influenced our results; these respondents had been excluded from the main analysis because the NSAL did not include a question about seasonal allergies, but this survey did assess asthma and all the four psychiatric outcomes.

All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 using survey procedures to account for complex sample design of the CPES.

Results

Table 1 shows descriptive characteristics of the analytic sample by lifetime history of psychopathology. The columns are not mutually exclusive; respondents with more than one psychiatric disorder appear in multiple columns. As expected, psychiatric disorders were highly comorbid. For example, 24.1% of respondents with a history of MDD also had a history of GAD. Approximately one-third (36.6%) of the sample had a lifetime history of seasonal allergies, and 11.5% had a history of asthma. The atopic conditions were also highly comorbid, with 20.5% of respondents with seasonal allergies also reporting asthma, and 60.0% of respondents with asthma also reporting seasonal allergies.

Table 1:

Descriptive characteristics of analytic sample

| MDD (n=2129) |

GAD (n=935) |

PD (n=577) |

PTSD (n=771) |

Whole sample (n=10309) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| 18–29 | 512 (21.9%) | 163 (16.6%) | 132 (19.7%) | 181 (22.1%) | 2608 (23.3%) |

| 30–45 | 755 (33.6%) | 321 (33.3%) | 208 (37.2%) | 266 (33.5%) | 3519 (29.3%) |

| 45–64 | 677 (35.5%) | 355 (40.0%) | 198 (35.1%) | 283 (40.1%) | 3082 (30.9%) |

| 65+ | 185 (8.9%) | 96 (10.1%) | 39 (8.0%) | 41 (4.3%) | 1100 (16.6%) |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 708 (36.7%) | 269 (32.7%) | 173 (32.2%) | 190 (25.4%) | 4492 (47.3%) |

| Female | 1421 (63.3%) | 555 (67.3%) | 404 (67.8%) | 581 (74.6%) | 5817 (52.7%) |

| Race | |||||

| Black | 144 (7.2%) | 70 (7.3%) | 43 (7.0%) | 85 (12.5%) | 712 (11.1%) |

| Hispanic | 536 (9.7%) | 190 (6.6%) | 140 (9.1%) | 185 (8.4%) | 3072 (11.7%) |

| Other | 271 (5.4%) | 91 (5.2%) | 66 (6.7%) | 73 (5.6%) | 2356 (6.4%) |

| White | 1178 (77.7%) | 584 (80.9%) | 328 (77.2%) | 428 (73.6%) | 4169 (70.8%) |

| Income-to-poverty ratio | |||||

| At or below poverty | 510 (21.8%) | 237 (21.8%) | 165 (27.2%) | 229 (26.3%) | 2546 (22.0%) |

| 2–3x poverty | 561 (27.0%) | 266 (28.7%) | 175 (28.6%) | 195 (25.6%) | 2755 (27.8%) |

| 4+ times poverty | 1058 (51.3%) | 432 (49.5%) | 237 (44.2%) | 347 (48.2%) | 5008 (50.2%) |

| Has health insurance | 1784 (85.6%) | 802 (87.2%) | 488 (87.1%) | 645 (85.2%) | 8518 (86.2%) |

| History of allergies | 873 (43.2%) | 429 (49.3%) | 249 (49.2%) | 339 (45.9%) | 3503 (36.6%) |

| History of asthma | 311 (13.4%) | 142 (15.2%) | 93 (14.4%) | 129 (14.7%) | 1195 (11.5%) |

| Allergy onset | |||||

| 0–12 | 265 (32.6%) | 126 (32.5%) | 76 (33.3%) | 120 (43.5%) | 969 (32.6%) |

| 13–18 | 125 (15.3%) | 64 (16.0%) | 48 (20.2%) | 53 (15.8%) | 543 (17.7%) |

| 19+ | 423 (52.1%) | 209 (51.6%) | 110 (46.5%) | 140 (40.6%) | 1771 (49.7%) |

| Asthma onset | |||||

| 0–12 | 116 (39.3%) | 38 (31.2%) | 22 (26.1%) | 41 (34.9%) | 510 (44.3%) |

| 13–18 | 36 (11.3%) | 22 (15.4%) | 8 (11.0%) | 17 (14.2%) | 141 (11.9%) |

| 19+ | 143 (49.4%) | 68 (53.4%) | 57 (62.8%) | 61 (50.9%) | 479 (43.8%) |

| Comorbid MDD | -- | 488 (52.2%) | 232 (37.8%) | 361 (43.7%) | -- |

| Comorbid GAD | 488 (24.1%) | -- | 171 (33.1%) | 228 (29.6%) | -- |

| Comorbid PD | 232 (10.3%) | 171 (19.6%) | -- | 144 (17.6%) | -- |

| Comorbid PTSD | 361 (17.4%) | 228 (25.5%) | 144 (25.7%) | -- | -- |

Values are unweighted N, weighted percentages.

Individuals with multiple disorders appear in multiple columns. MDD = Major Depressive Disorder, GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder, PD = Panic Disorder, PTSD = Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Figure 1 shows the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of the relationships between seasonal allergies (green) and asthma (black) with each of the four psychiatric disorders. P-values are also included, to allow for comparison against the Bonferroni-adjusted multiple testing significance threshold of 0.0125. Seasonal allergies were significantly associated with MDD (Odds ratio (OR): 1.24; 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.06–1.46), GAD (OR: 1.54; 95% CI: 1.28–1.84), PD (OR: 1.54, 95% CI: 1.24 −1.91), and PTSD (OR: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.09–1.59). While all point estimates for asthma were greater than 1.0, asthma was not statistically significantly associated with any psychiatric outcome after adjustment for multiple comparisons. The sensitivity analysis examining the association between asthma and history of panic attack, instead of PD, also did not reach statistical significance (OR: 1.26, 95% CI: 0.93–1.70). As shown in Table 2 the relationships between allergies and each psychiatric disorder remained after controlling for psychiatric comorbidity. In some cases results were no longer significant after accounting for multiple comparisons, however effect estimates remained similar to those produced by the original models, indicating that adjustment for comorbid conditions did not attenuate the relationship.

Figure 1:

Odds ratios for associations between atopic disorders and psychiatric disorders

Note: All models adjusted for age, sex, race income-to-poverty ratio, and health coverage status. All results are given as OR (95% CI). The recommended p-value significance threshold is 0.0125, which applies a Bonferroni adjustment to account for the use of four tests per exposure.

MDD = Major Depressive Disorder, GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder, PD = Panic Disorder, PTSD = Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Table 2:

Association between seasonal allergies and each psychiatric disorder, after controlling for each other psychiatric disorder

| MDD | GAD | PD | PTSD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original model | 1.24 (1.06–1.46)* | 1.54 (1.28–1.84)* | 1.54 (1.24–1.91)* | 1.32 (1.09–1.59)* |

| Controlling for MDD | -- | 1.47 (1.24–1.74)* | 1.49 (1.20–1.83)* | 1.26 (1.05–1.51) |

| Controlling for GAD | 1.16 (0.98–1.37) | -- | 1.41 (1.12–1.77)* | 1.22 (1.01–1.49) |

| Controlling for PD | 1.21 (1.03–1.43) | 1.47 (1.22–1.77)* | -- | 1.27 (1.05–1.54) |

| Controlling for PTSD | 1.21 (1.03–1.42) | 1.49 (1.24–1.79)* | 1.47 (1.19–1.81)* | -- |

Note: All models are adjusted for age, sex, race, income-to-poverty ratio, and health coverage status.

MDD = Major Depressive Disorder, GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder, PD = Panic Disorder, PTSD = Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

= Remains significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons.

We then examined whether age-of-onset (childhood, teen years, or adulthood) of atopy influenced the relationship between the disorder and psychopathology (Table 3). Among people with allergies, those whose allergies began before age 12 were 1.81 times more likely to have a lifetime history of PTSD than those whose allergies began in adulthood. There was no evidence that age of onset of allergies was related to the other three psychiatric conditions after adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Table 3:

Timing of atopic onset and risk of psychopathology

| MDD | GAD | PD | PTSD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allergy age at onset (ref=19+) | ||||

| 0–12 | 0.93 (0.73–1.20) | 1.08 (0.79–1.48) | 1.17 (0.84–1.61) | 1.81 (1.28–2.55)* |

| 13–18 | 0.81 (0.61–1.08) | 1.01 (0.71–1.44) | 1.42 (0.85–2.35) | 1.27 (0.83–1.94) |

| Asthma age at onset (ref 19+) | ||||

| 0–12 | 0.64 (0.45–0.92) | 0.66 (0.34–1.31) | 0.50 (0.23–1.12) | 1.03 (0.53–2.01) |

| 13–18 | 0.62 (0.31–1.25) | 1.35 (0.58–3.11) | 0.77 (0.28–2.10) | 1.67 (0.80–3.50) |

Note: This model examines whether, given that an individual has an atopic disorder, a younger age-at-onset of allergies is associated with greater odds of psychopathology. Allergy N=3290, asthma N=1137. Odds ratios are adjusted for age, sex, race, income:poverty ratio, and health coverage status. MDD = Major Depressive Disorder, GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder, PD = Panic Disorder, PTSD = Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

= Remains significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Two sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of these results. As shown in Supplementary table S1, all associations between lifetime psychopathology and lifetime history of seasonal allergies replicated when using past-year definitions of the exposure and outcomes. As shown in Supplementary tables S2 and S3, the relationships between psychopathology and asthma still did not reach statistical significance even after including the NSAL in the analytic sample.

Discussion

This study used a large, community-based sample to simultaneously examine the relationship between multiple psychiatric disorders and seasonal allergies and asthma, two common atopic conditions. The primary finding of this study is that a history of seasonal allergies is consistently associated with greater odds of MDD, GAD, PD, and PTSD. Allergies that began earlier in life were more strongly related to likelihood of PTSD than those that began in adulthood. Contrary to expectation, there were no significant associations between asthma and any psychiatric disorder, although all estimates were in the expected direction. The results of this study indicate that the relationship between atopy and psychopathology is more complex and nuanced than previously suggested.

The finding that seasonal allergies are associated with a broad range of psychopathology is consistent with prior literature. There is a widely-replicated association between MDD and allergies, and previous studies have suggested similar associations with allergies may exist for PD (26, 27). To our knowledge, this is the first study to report seasonal allergies as a possible risk factor for PTSD. Although trauma and adversity are risk factors for psychopathology in general, PTSD is unique in requiring a precipitating trauma as part of diagnostic criteria (43). Informed by these results, future studies should explore whether atopy-related inflammation exacerbates psychiatric symptoms following trauma, or whether atopy-related systemic inflammation at the time of the trauma influences susceptibility to developing PTSD.

There are several potential mechanisms that may contribute to the observed relationship between allergies and this broad range of psychopathology. Systemic inflammation due to an atopic response may act on the brain in a manner that produces or exacerbates psychiatric symptoms(15, 16). In addition, inflammation from atopic responses during childhood or adolescence may influence development at critical periods (50–52), consistent with the finding that earlier age of onset of allergies was more strongly associated with PTSD than allergies which onset later. Alternatively, genetic factors associated with propensity towards atopy may also be associated with susceptibility to psychiatric disorders (53, 54). The finding that allergies are related to range of psychopathology may also suggest that allergies may be associated with an underlying factor common to several disorders, such as one of the domains, systems, or processes described in the National Institute for Mental Health’s Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) (55, 56).

Contrary to our expectations, asthma was not significantly associated with any form of psychopathology in our results. There are multiple potential explanations for these findings. It is possible that the differing results for allergies and asthma may result from an underlying biological difference between the two conditions, such as allergies having a greater ability to affect the brain due to the nose-to-brain pathway.(57, 58) However, some of the associations for asthma have replicated across other studies,(22, 23) particularly panic symptomology (24, 25), so the lack of replication in our study requires consideration of other factors that could have led to differing results. First, many prior studies were conducted with child or adolescent samples (59–61), and our analysis was restricted to adults. If the relationship between asthma and PD was stronger earlier rather than later in the life course, this may contribute to these disparate findings. However, the asthma-PD association has been replicated other large community-based studies of adults (22, 23, 25). Another possible reason for the null results may be a result of how history of asthma was assessed, which was dependent on a reporting a physician diagnosis of this condition. This means that assessment of asthma could be correlated with access to medical care, a possibility we attempted to account for by adjusting for health insurance coverage status.

These findings should be interpreted in light of the study strengths and limitations. Data on history of allergies or asthma and their ages at onset was obtained via self-report. It is possible that individuals with a history of psychopathology may be more likely to report health conditions such as seasonal allergies, as has been found in another study of allergies and anxiety (62). While we attempted to use age of onset information to address temporality, the retrospective design of this study (examining lifetime and past-year history) means that we cannot be certain of the directionality and temporality of the observed associations. However, because this design assesses occurrence of disorder in a longer period of time (one lifetime or one year) it avoids the possibility of confounding by seasonality, which would be a concern in a cross-sectional study due to the potential for seasonal patterns in atopic and psychiatric disorders. Finally, we do not adjust for medication use (either antidepressants or antihistamines) because we consider these drugs to be proxy indicators of our main exposures and outcome, so adjusting for these medications would both result in multi-collinearity and bias our results towards the null. This study also has several strengths, including the use of a well-validated diagnostic interview to assess a range of psychiatric disorders in a large community-based sample and multiple sensitivity analyses to assess robustness of the results. By examining multiple psychiatric outcomes assessed using the same instrument in the same sample, this analysis provides among the most complete assessments of the relationship between allergies and asthma with common psychiatric disorders in a manner that allows for direct comparisons across these four conditions.

Further study is needed to understand the relationship between psychopathology and atopy. Longitudinal examination of underlying emotional, behavioral, and biological systems as they relate to atopy, consistent with the RDoC framework, are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Major Depressive Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder, and Post-traumatic Stress Disorder were all significantly associated with seasonal allergies

These associations replicated across both lifetime disease history and current disease status

The multiple associations between seasonal allergies and psychiatric disorders were not explained by comorbidity between the psychiatric disorders

No significant association was found between any psychiatric disorder and asthma

Funding

B Mezuk was supported by K01-MH093642-A1. KM Kelly is supported by National Institute of Health Training Program in Genomic Science at the University of Michigan (T32-HG00040). The Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys were supported by NIMH (U01-MH60220, U01-MH57716, U01-MH062209, U01-MH62207), and received supplemental support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (grant 044708), NIDA, SAMHSA, NIH OBSSR, the Latino Research Program Project (P01-MH059876), and the John W. Alden Trust. The sponsors had no role in the design, analysis, or interpretation of the results

Acronyms:

- MDD

Major Depressive Disorder

- GAD

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

- PD

Panic Disorder

- PTSD

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- IPR

Income-to-poverty ratio

- NIMH

National Institute for Mental Health

- RDoC

Research Domain Criteria

- CIDI

Composite International Diagnostic Interview

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

References

- 1.Johansson SGO, Bieber T, Dahl R, Friedmann PS, Lanier BQ, Lockey RF, et al. (2004): Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use: Report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization, October 2003. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 113: 832–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willemsen G, TCEM van Beijsterveldt, CGCM van Baal, D Postma, DI Boomsma (2008): Heritability of Self-Reported Asthma and Allergy: A Study in Adult Dutch Twins, Siblings and Parents. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 11: 132–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strachan DP, Wong HJ, Spector TD (2001): Concordance and interrelationship of atopic diseases and markers of allergic sensitization among adult female twins. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 108: 901–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ker J, Hartert TV (2009): The atopic march: what’s the evidence? Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 103: 282–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinart M, Benet M, Annesi-Maesano I, von Berg A, Berdel D, Carlsen KCL, et al. (2014): Comorbidity of eczema, rhinitis, and asthma in IgE-sensitised and non-IgE-sensitised children in MeDALL: a population-based cohort study. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2: 131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fagnani C, Annesi-Maesano I, Brescianini S, D’Ippolito C, Medda E, Nisticò L, et al. (2008): Heritability and Shared Genetic Effects of Asthma and Hay Fever: An Italian Study of Young Twins. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 11: 121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nystad W, Røysamb E, Magnus P, Tambs K, Harris JR (2005): A comparison of genetic and environmental variance structures for asthma, hay fever and eczema with symptoms of the same diseases: a study of Norwegian twins. Int J Epidemiol. 34: 1302–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wood LG, Baines KJ, Fu J, Scott HA, Gibson PG (2012): THe neutrophilic inflammatory phenotype is associated with systemic inflammation in asthma. Chest. 142: 86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ólafsdottir IS, Gislason T, Thjodleifsson B, Olafsson Í, Gislason D, Jögi R, Janson C (2005): C reactive protein levels are increased in non-allergic but not allergic asthma: a multicentre epidemiological study. Thorax. 60: 451–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borish L (2003): Allergic rhinitis: Systemic inflammation and implications for management. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 112: 1021–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yokoyama A, Kohno N, Fujino S, Hamada H, Inoue Y, Fujioka S, et al. (1995): Circulating interleukin-6 levels in patients with bronchial asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 151: 1354–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gosset P, Malaquin F, Delneste Y, Wallaert B, Capron A, Joseph M, Tonnel A-B (1993): Interleukin-6 and interleukin-1α production is associated with antigen-induced late nasal response. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 92: 878–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howren MB, Lamkin DM, Suls J (2009): Associations of Depression With C-Reactive Protein, IL-1, and IL-6: A Meta-Analysis: Psychosomatic Medicine. 71: 171–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK, Lanctôt KL (2010): A Meta-Analysis of Cytokines in Major Depression. Biological Psychiatry, Cortical Inhibitory Deficits in Depression. 67: 446–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raison CL, Capuron L, Miller AH (2006): Cytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends in Immunology. 27: 24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller AH, Maletic V, Raison CL (2009): Inflammation and Its Discontents: The Role of Cytokines in the Pathophysiology of Major Depression. Biological Psychiatry, Social Stresses and Depression. 65: 732–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanna L, Stuart AL, Pasco JA, Jacka FN, Berk M, Maes M, et al. (2014): Atopic disorders and depression: findings from a large, population-based study. J Affect Disord. 155: 261–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hurwitz EL, Morgenstern H (1999): Cross-Sectional Associations of Asthma, Hay Fever, and Other Allergies with Major Depression and Low-Back Pain among Adults Aged 20–39 Years in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 150: 1107–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen M-H, Su T-P, Chen Y-S, Hsu J-W, Huang K-L, Chang W-H, Bai Y-M (2013): Allergic rhinitis in adolescence increases the risk of depression in later life: A nationwide population-based prospective cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 145: 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen P, Pine DS, Must A, Kasen S, Brook J (1998): Prospective Associations between Somatic Illness and Mental Illness from Childhood to Adulthood. Am J Epidemiol. 147: 232–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loerbroks A, Apfelbacher CJ, Bosch JA, Stürmer T (2010): Depressive Symptoms, Social Support, and Risk of Adult Asthma in a Population-Based Cohort Study: Psychosomatic Medicine. 72: 309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodwin RD, Jacobi F, Thefeld W (2003): Mental disorders and asthma in the community. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 60: 1125–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott KM, Von Korff M, Ormel J, Zhang M, Bruffaerts R, Alonso J, et al. (2007): Mental Disorders among Adults with Asthma: Results from the World Mental Health Surveys. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 29: 123–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katon WJ, Richardson L, Lozano P, McCauley E (2004): The relationship of asthma and anxiety disorders. Psychosom Med. 66: 349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hasler G, Gergen PJ, Kleinbaum DG, Ajdacic V, Gamma A, Eich D, et al. (2005): Asthma and Panic in Young Adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 171: 1224–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodwin RD (2002): Self-reported hay fever and panic attacks in the community. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 88: 556–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kennedy BL, Morris RL, Schwab JJ (2002): Allergy in panic disorder patients: a preliminary report1. General Hospital Psychiatry. 24: 265–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodwin RD, Olfson M, Shea S, Lantigua RA, Carrasquilo O, Gameroff MJ, Weissman MM (2003): Asthma and mental disorders in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry. 25: 479–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patten SB, Williams JVA (2007): Self-Reported Allergies and Their Relationship to Several Axis I Disorders in a Community Sample. Int J Psychiatry Med. 37: 11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weisberg RB, Bruce SE, Machan JT, Kessler RC, Culpepper L, Keller MB (2002): Nonpsychiatric Illness Among Primary Care Patients With Trauma Histories and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. PS. 53: 848–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodwin RD, Fischer ME, Goldberg J (2007): A Twin Study of Post–Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms and Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 176: 983–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kean EM, Kelsay K, Wamboldt F, Wamboldt MZ (2006): Posttraumatic Stress in Adolescents With Asthma and Their Parents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 45: 78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sledjeski EM, Speisman B, Dierker LC (2008): Does number of lifetime traumas explain the relationship between PTSD and chronic medical conditions? Answers from the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R). J Behav Med. 31: 341–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tonelli LH, Katz M, Kovacsics CE, Gould TD, Joppy B, Hoshino A, et al. (2009): Allergic rhinitis induces anxiety-like behavior and altered social interaction in rodents. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 23: 784–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang PS, Angermeyer M, Borges G, Bruffafaerts R, Tat Chiu W, de Girolamo G, et al. (2007): Delay and failure in treatment seeking after first onset of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 6: 177–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.GG Du Fort MD, Newman SC MD, Bland RC MB (1993): Psychiatric Comorbidity and Treatment Seeking: Sources of Selection Bias in the Study of Clinical Populations. Journal of Nervous. 181: 467–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE (2005): Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general psychiatry. 62: 617–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alegria M, Jackson JS, Kessler RC, Takeuchi D (2008): National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCSR). Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES), 2001–2003 [Computer file]. ICPSR20240-v5. Retrieved from https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/studies/20240/version/8.

- 39.Heeringa SG, Wagner J, Torres M, Duan N, Adams T, Berglund P (2004): Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 13: 221–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pennell B-E, Bowers A, Carr D, Chardoul S, Cheung G, Dinkelmann K, et al. (2004): The development and implementation of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, the National Survey of American Life, and the National Latino and Asian American Survey. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 13: 241–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, Demler O, Heeringa S, Hiripi E, et al. (2004): The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 13: 69–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kessler RC, Abelson J, Demler O, Escobar JI, Gibbon M, Guyer ME, et al. (2004): Clinical calibration of DSM-IV diagnoses in the World Mental Health (WMH) version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 13: 122–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Psychiatric Association (n.d.): Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSMIV, 4th ed Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Torén K, Palmqvist M, Löwhagen O, Balder B, Tunsäter A (2006): Self-reported asthma was biased in relation to disease severity while reported year of asthma onset was accurate. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 59: 90–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bauchau V, Durham SR (2004): Prevalence and rate of diagnosis of allergic rhinitis in Europe. Eur Respir J. 24: 758–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Manalai P, Hamilton RG, Langenberg P, Kosisky SE, Lapidus M, Sleemi A, et al. (2012): Pollen-specific immunoglobulin E positivity is associated with worsening of depression scores in bipolar disorder patients during high pollen season. Bipolar Disorders. 14: 90–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lupien SJ, McEwen BS, Gunnar MR, Heim C (2009): Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 10: 434–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andersen SL (2003): Trajectories of brain development: point of vulnerability or window of opportunity? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, Brain Development, Sex Differences and Stress: Implications for Psychopathology; 27: 3–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Proctor B, Dalaker J (n.d.): Poverty in the United States: 2001. Current Population Reports. US Census Bureau; Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/p60-219.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buske-Kirschbaum A, von Auer K, Krieger S, Weis S, Rauh W, Hellhammer D (2003): Blunted Cortisol Responses to Psychosocial Stress in Asthmatic Children: A General Feature of Atopic Disease? Psychosomatic Medicine. 65: 806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hagberg H, Gressens P, Mallard C (2012): Inflammation during fetal and neonatal life: Implications for neurologic and neuropsychiatric disease in children and adults. Ann Neurol. 71: 444–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Calderón-Garcidueñas L, Engle R, Mora-Tiscareño A, Styner M, Gómez-Garza G, Zhu H, et al. (2011): Exposure to severe urban air pollution influences cognitive outcomes, brain volume and systemic inflammation in clinically healthy children. Brain and Cognition. 77: 345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wamboldt MZ, Hewitt JK, Schmitz S, Wamboldt FS, Räsänen M, Koskenvuo M, et al. (2000): Familial association between allergic disorders and depression in adult Finnish twins. Am J Med Genet. 96: 146–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Timonen M, Jokelainen J, Herva A, Zitting P, Meyer-Rochow VB, Räsänen P (2003): Presence of atopy in first-degree relatives as a predictor of a female proband’s depression: Results from the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 111: 1249–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cuthbert BN, Insel TR (2013): Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: the seven pillars of RDoC. BMC Medicine. 11: 126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, et al. (2010): Research Domain Criteria (RDoC): Toward a New Classification Framework for Research on Mental Disorders. AJP. 167: 748–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pardeshi CV, Belgamwar VS (2013): Direct nose to brain drug delivery via integrated nerve pathways bypassing the blood–brain barrier: an excellent platform for brain targeting. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery. 10: 957–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tonelli LH, Postolache TT (2010): Airborne inflammatory factors: “from the nose to the brain.” Front Biosci (Schol Ed). 2: 135–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Katon W, Lozano P, Russo J, McCauley E, Richardson L, Bush T (2007): The Prevalence of DSM-IV Anxiety and Depressive Disorders in Youth with Asthma Compared with Controls. Journal of Adolescent Health. 41: 455–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ortega AN, Huertas SE, Canino G, Ramirez R, Rubio-Stipec M (2002): Childhood Asthma, Chronic Illness, and Psychiatric Disorders. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 190: 275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goodwin RD, Pine DS, Hoven CW (2003): Asthma and Panic Attacks Among Youth in the Community. Journal of Asthma. 40: 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gregory AM, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Milne BJ, Poulton R, Sears MR (2009): Links Between Anxiety and Allergies: Psychobiological Reality or Possible Methodological Bias? Journal of Personality. 77: 347–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.