ABSTRACT

Facing an unprecedented surge of patient volumes and acuity, institutions around the globe called for volunteer healthcare workers to aid in the effort against COVID-19. Specifically being sought out are retirees. But retired healthcare workers are taking on significant risk to themselves in answering these calls. Aside from the risks that come from being on the frontlines of the epidemic, they are also at risk due to their age and the comorbidities that often accompany age. If, for current or future COVID efforts, we as a society will be so bold as to exhort a vulnerable population to take on further risk, we must use much care and attention in how we involve them in this effort. Herein we describe the multifaceted nature of the risks that retired healthcare workers are taking by entering the COVID-19 workforce as well as suggest ways in which we might take advantage of their medical skills and altruism yet while optimizing caution and safety.

KEYWORDS: Coronavirus, COVID-19, healthcare workers, retirees, SARS-CoV-2

Facing unprecedented volumes amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, many states and countries have called for volunteer healthcare workers (HCWs) [1–4]. But most healthcare workers must staff their own institutions’ developing COVID efforts and are not free to leave for another part of the country or the world. Few have the financial position to quit their jobs or close their practices for an indefinite period of time to become unpaid volunteers elsewhere. As such – who are left? Who are the workers with training in healthcare who also are not currently working? Retirees. And these are being specifically called out by government leaders [5]. Yet bringing this group in to fight a novel and potent virus, if done at all, needs to be handled with caution and care.

COVID-19 infection is a serious risk to all healthcare workers, retired or not. One early report from China noted that nearly one-third of hospitalized COVID-19 patients were healthcare personnel [6]. While this may be due to an initial lack of awareness about the virus’s transmissibility, recent reports also show alarming numbers elsewhere. In Spain, 14% of cases occurred in HCWs. In one province in Italy, it was 15% [7]. Numbers were not much better in the USA. The Centers for Disease Control published findings from 315,531 cases reported from 12 February to 9 April. Of those with information regarding occupation, 1 in 5 were identified as healthcare workers [8]. The real number is undoubtedly higher because only 16% of records included employment data. Indeed, while only 3% of COVID-positive cases represented healthcare personnel overall, the proportion was 11% in states with more complete reporting.

These disproportionate numbers are due to the likelihood that HCWs are more at risk for infection than the general public – at least in large part due to the multifaceted nature of their exposure to the virus [9]. In addition to the baseline risk of infection/contagion in the community, HCWs are at the frontlines of this pandemic, working in the midst of a sea of infected patients. Surely, it is not only the amount of exposure at any given time (number of patients and frequency of exposures), but the duration of exposure that is putting them at risk (number of hours exposed). Another factor is that HCWs are confronted with patients with more severe illness; those with mild illness do not present to the hospital as frequently. Those with more severe disease carry higher viral loads but also shed virus for longer periods of time [10,11]. Additionally, social distancing of 6 feet or more is virtually impossible in the hospital setting, particularly in those hospitals overrun with patients being cared for in hallways. Patients are in close physical contact with HCWs by necessity – in order to receive medications, have intravenous lines placed, get blood drawn, have vital signs checked – and be placed on ventilators. In other words, social distancing does not apply – cannot apply – in medical settings.

The hazard to healthcare personnel comes not only due to the nature of their exposure to the virus but also relates to practices that put them at risk. The seemingly ubiquitous and unremitting problem of insufficient or inadequate personal protective equipment (PPE) is well known. Furthermore, fatigue heralds increased risk. Medical errors related to sleep deprivation and fatigue were the basis for the ACGME’s efforts to mitigate the impact of extended work hours [12]. But duty hours do not apply to attending physicians and nurses – and certainly not during a pandemic. It is to be expected, then, that physically and mentally exhausted workers will inadvertently fail to decontaminate themselves properly at times. Indeed, many studies have shown that doffing of PPE often leads to self-contamination in HCWs even during simple simulation exercises [13]. How much more so would this be a reality in wearied HCWs after a 12-hour (really, 14- or 15-hour) shift?

Regardless of the specific mechanisms for these alarming rates of infection, our HCWs must confront these unavoidable risks daily – but retirees face additional risks because of their age. COVID-19 infection poses a real and serious danger to our older population. Study after study has confirmed age as the greatest and most consistent risk factor for poor outcomes [14]. The case-fatality rate of COVID-19 increases with age, leaping two- to fourfold when comparing those in their 60s to those in their 70s [15]. At baseline, older patients are weaker, more frail, and with less physiologic reserve to be able to withstand a serious systemic illness. Indeed, the elderly are also more likely to have comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension. These conditions, apart from the usual morbidity that they cause for any given person, may additionally have mechanisms by which they confer increased coronavirus-specific risk as well [6,15].

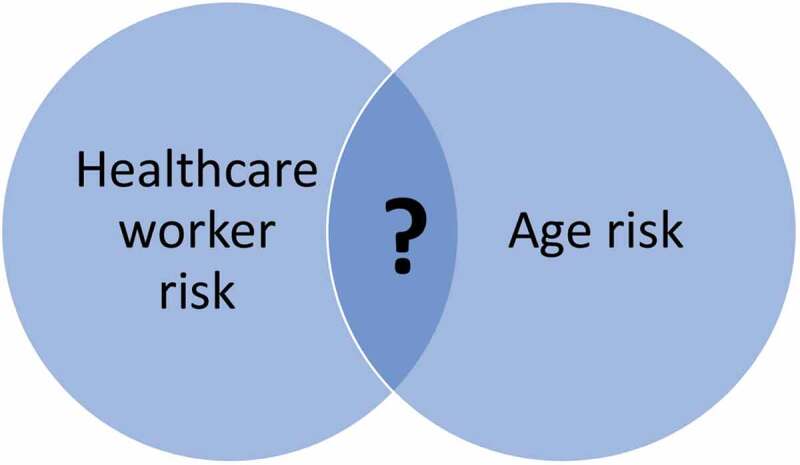

This leads to our proposition: in enlisting retired healthcare workers into the fight against COVID-19, we merge two known and accepted risk factors into a larger threat, the magnitude of which is as yet unknown (Figure 1). It is understandable to view retired HCWs as an available and able resource to overcome the strain on our hospitals, but we must remember that these vulnerable volunteers are older, may have comorbidities, and are being asked to serve at the frontlines of contagion. In one study, the median age of physicians who died after contracting coronavirus was 66 years [16]. In the aforementioned CDC report, while only 6% of infected healthcare personnel were 65 years or older, they represented 37% of deaths. By merging independent risk factors, we are inevitably increasing the threat of infection in this group of individuals.

Figure 1.

While being a healthcare worker and a person of older age are independent risk factors for COVID-19 illness, the combined effects in older healthcare workers is unknown.

There are other ways by which we might place older healthcare workers in harm’s way. With the urgency of pleas for help, and states even having waved or rapidly approved medical licensure, we may be rushing these HCWs into situations for which they lack proper training – or any training at all [17,18]. The greatest need, for example, has been in critical care and emergency medicine, yet surely only a fraction of volunteers come from these subspecialties. Moreover, modern forms of PPE including techniques of donning/doffing are rarely employed by most specialists outside of infectious disease and related disciplines. Many retirees may not have had much experience with PPE during their careers or, if they have, it was some time ago. Finally, these HCWs may bring the virus home to their spouses or partners who are likely of similar age and health status. To then insist on isolation or time away from home would only increase the emotional burden already placed on elderly volunteers.

‘The thought of going back to work fills me and my family with some anxiety, but if I am called, then I will go,’ wrote one 70-year-old retired neurosurgeon [19]. But, how best can we – should we – involve such volunteers? Certainly, we should follow the baseline precautions recommended for all healthcare professionals. While protecting them, we should also be creative and deliberate in how we might employ their skills. Retired nurses and physicians can manage non-COVID patients; after all, cancer and heart disease do not stop in the midst of a pandemic. They can provide telehealth triage or consultations, help with research or epidemiologic efforts, provide patient and family education or support, and assist hospital administration. Others might work in the nursery, answer phones, perform errands, deliver medications for the inpatient pharmacy, take vital signs, keep abreast of the medical literature, or be friendly visitors for non-COVID patients that are not allowed family visits because of hospital-wide regulations [20]. Such efforts would allow older HCWs to use their medical knowledge and experience – yet remain at lower risk of nosocomial COVID-19 infection.

The enthusiastic response to volunteer observed in retirees reveals that many former healthcare professionals are still eager to work and contribute to society. Indeed, this hidden gem may continue to shine after the pandemic is over. Nevertheless, we must meet their altruism with care, and their enthusiasm with discernment. If, with current or future COVID efforts, we are so bold as to ask our retirees to serve on the frontlines, then let us do so with the utmost care and preparation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1].Connelly E. Italy calls in retired doctors to help combat coronavirus epidemic. 2020. [cited 2020 March7]. Accessed April 24, 2020. Available from: https://nypost.com/2020/03/07/italy-calls-in-retired-doctors-to-help-combat-coronavirus-epidemic/

- [2].Lemon J. New york governor asks retired doctors and nurses to sign up and be on call amid coronavirus crisis. 2020. [cited 2020 March17]. Accessed April 24, 2020. Available from: https://www.newsweek.com/new-york-governor-asks-retired-doctors-nurses-sign-call-amid-coronavirus-crisis-1492825

- [3].Halpic P, Luelmo P.. Retired doctors, medics abroad answer coronavirus calls. 2020. [cited 2020 April1]. Accessed April 24, 2020. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-healthcare/retired-doctors-medics-abroad-answer-coronavirus-calls-idUSKBN21J5PD

- [4].Sternlicht A. 76,000 healthcare workers have volunteered to help NY hospitals fight coronavirus. [cited 2020 March29]. Accessed April 24, 2020. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/alexandrasternlicht/2020/03/29/76000-healthcare-workers-have-volunteered-to-help-ny-hospitals-fight-coronavirus/#2ce120b11d32

- [5].Stephens S. Retired but fired up to come back against coronavirus. 2020. [cited 2020 March19]. Accessed April 24, 2020. Available from: https://www.healthecareers.com/article/healthcare-news/retired-but-fired-up-to-come-back-against-coronavirus

- [6].Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Minder R, Peltier E. Virus knocks thousands of health workers out of action in Europe. 2020. [cited 2020 March24]. Accessed April 26, 2020. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/24/world/europe/coronavirus-europe-covid-19.html

- [8].Team CC-R . Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19 — USA, February 12–April 9, 2020. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Rep. 2020;69(15):477–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Howard J. Health care workers getting sicker from coronavirus than other patients, expert says. 2020. Accessed April 26, 2020. Available from: https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/16/health/doctors-coronavirus-health-care-hit-harder/index.html

- [10].Liu Y, Yan LM, Wan L, et al. Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Jun;20(6):656–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Xu K, Chen Y, Yuan J, et al. Factors associated with prolonged viral RNA shedding in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Jun;20(6):656–657. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Education ACfGM . History of duty hours. Accessed April 27, 2020. Available from: https://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Clinical-Experience-and-Education-formerly-Duty-Hours/History-of-Duty-Hours

- [13].Verbeek JH, Rajamaki B, Ijaz S, et al. Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;4:CD011621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wang Y, Lu X, Chen H, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of 344 intensive care patients with COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020. DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0736LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ing E, Xu A, Salimi A, et al. Physician deaths from corona virus disease (COVID-19). 2020. [cited 2020 April8]. Accessed April 23, 2020. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.05.20054494v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [17].States expediting licensure for inactive/retired licensees in response to COVID-19 [press release]. Accessed April 26, 2020. www.fsmb.org2020

- [18].Doherty T. States waiving medical license regulations for workforce surge. 2020. [cited 2020 April2]. Accessed April 27, 2020. Available from: https://www.politico.com/f/?id=00000171-3cab-d92d-a5ff-fcaba8370000

- [19].Marsh H. Surgeon Henry Marsh: Covid-19 and the doctor’s dilemma. 2020. [cited 2020 March27]. Accessed April 23, 2020. Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/00312c48-6e87-11ea-9bca-bf503995cd6f

- [20].Mansoor S. ‘I’ve been missing caring for people’. Thousands of Retired Health Care Workers Are Volunteering to Help Areas Overwhelmed By Coronavirus 2020. [cited 2020 March26]. Accessed April 24, 2020.Available from: https://time.com/5810120/retired-health-care-workers-coronavirus/