Abstract

Objective

Cerebral edema is the predominant mechanism of secondary inflammation after intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). Pioglitazone, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonist has been shown to play a role in regulation of central nervous system inflammation. Here, we examined the pharmacological effects of pioglitazone in an ICH mouse model and investigated its regulation on NLRP3 inflammasome and glucose metabolism.

Methods

The ICH model was established in C57 BL/6 mice by the stereotactical inoculation of blood (30 µL) into the right frontal lobe. The treatment group was administered i.p. pioglitazone (20 mg/kg) for 1, 3, and 6 days. The control group was administered i.p. phosphate-buffered saline for 1, 3, and 6 days. We investigated brain water contents, NLRP3 expression, and changes in the metabolites in the ICH model using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.

Results

On day 3, brain edema in the mice treated with pioglitazone was decreased more than that in the control group. Expression levels of NLRP3 in the ICH model treated with pioglitazone were decreased more than those of the control mice on days 3 and 7. The pioglitazone group showed higher levels of glycolytic metabolites than those in the ICH mice. Lactate production was increased in the ICH mice treated with pioglitazone.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrated less brain swelling following ICH in mice treated with pioglitazone. Pioglitazone decreased NLRP3-related brain edema and increased anaerobic glycolysis, resulting in the production of lactate in the ICH mice model. NLRP3 might be a therapeutic target for ICH recovery.

Keywords: Cerebral hemorrhage, Brain edema, Inflammasomes, Pioglitazone, Lactates

INTRODUCTION

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), accounts for 10–15% of all stroke types with high morbidity and mortality [24]. Hematoma formation and cerebral edema begin within hours by extravasation of blood products into the brain parenchyma and lasts for weeks [17]. Thus, increasing intracranial pressure leads to neurological deterioration [23].

Neuroinflammation is known as a major contributor and hallmark of brain injury caused by ICH [3,38]. NLRP3 is activated in response to pathogens, several pathogen-associated molecular patterns, danger-associated molecular patterns, and environmental irritants [31]. Activation of NLRP3 is a critical component of the inflammasome and plays an independent role in injury signaling, apart from other inflammasome components [32,34]. Finally, it can lead to cell death [20,39]. However, inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome has been shown to suppress the inflammatory response and reduce cell death [21,43]. Recently, pioglitazone, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) agonist, reduced cerebral edema and immune response after traumatic brain injury by downregulating the effects of NLRP3 [15].

Metabolites have an important role in biology as structures of the genome, proteomes, and cell membranes. Additionally, they have other functions as signaling molecules, energy sources, and metabolic intermediates. Mass spectroscopy (MS) remains the most favored technology for metabolomics due to its wide dynamic range and good sensitivity in the nanomolar range [19]. However, few studies have reported metabolomic analyses in hemorrhagic stroke patients [4]. In the present study, we investigated the effect of pioglitazone on NLRP3-related brain edema and glucose metabolism in an animal model of ICH.

MATERIALs AND METHODS

This study was approved by Institutional Review Board of The Catholic University of Korea St. Vincent’s Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IRB No. 17-8).

ICH mouse model

Six-week-old male C57/BL mice (Central Laboratory Animals, Seoul, Korea) were used. The mice were housed in a standardized animal room (lights on 7 am to 7 pm, room temperature 22±2°C The mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and a midline incision was made in the head. Then, they were inoculated stereotactically with arterial blood (30 µL) into the right frontal lobe (2 mm lateral and 1 mm posterior to the bregma at a depth of 2.5 mm from the skull) using a sterile Hamilton syringe fitted with a 26-gauge needle (Hamilton, Reno, NV, USA) and a microinfusion pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA). The needle was left in place for an additional 5 minutes after injection to prevent possible leakage. It was slowly withdrawn within 2 minutes [28]. Following the surgery, the skull hole was sealed with bone wax and the incision was closed with sutures and the mice were allowed to recover. To avoid postsurgical dehydration, 0.5 mL of normal saline was given to each mouse by subcutaneous injection immediately after surgery.

Sample preparation for the assessment of brain edema

After the mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation, the brain was removed and the cerebrum was dissected from the brain stem. The wet weight of the cerebrum was measured and the cerebrum was dried in a dry oven at 100°C for 30 hours. The dry weight was then determined. The water content of the brain was calculated as follows : water content = [(wet weight – dry weight) / wet weight] × 100% [9].

Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted using a PhosSTOP EASYpack (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and detected with antibodies against NLRP3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, Co., St. Louis, MO, USA). Immunoreactivity was detected using the ECL chemiluminescence system and quantified using an imaging densitometer. The density of each band was quantified using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

Brain tissue (50–100 mg) was homogenized using a TissueLyzer (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) with 400 µL of chloroform/methanol (2/1). The homogenate was incubated for 20 minutes at 4°C. Glutamine-d4 was added to each sample as an internal standard after incubation and mixed well. The sample was then centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 10 minutes. The supernatant was collected and 100 µL of H2O was added. The sample was mixed vigorously and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 20 minutes. The upper phase was taken and dried under vacuum. The dried sample was stored at -20°C and reconstituted with 40 µL of H2O/acetonitrile (50/50 v/v) prior to LC-MS/MS analysis

Metabolites related to energy metabolism were analyzed with an LC-MS/MS equipped with a 1290 HPLC (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), Qtrap 5500 (ABSciex, Flamingham, MA, USA) and a 50×2 mm reverse phase column (Synergi Fusion-RP). Then, 3 µL was injected into the LC-MS/MS system and ionized with a turbo spray ionization source. Ammonium acetate (5 mM in H2O) and 5 mM ammonium acetate in acetonitrile were used as mobile phases A and B, respectively. The separation gradient was as follows : hold at 0% B for 5 minutes, 0 % to 90% B for 2 minutes, hold at 90% for 8 minutes, 90% to 0% B for 1 minute, then hold at 0% B for 9 minutes. The LC flow rate was set at 70 µL/min, except for 140 µL/min from 7 to 15 minutes. The column temperature was maintained at 23°C. Multiple reaction monitoring was used in the negative ion mode. Extracted ion chromatogram (EIC) corresponding to the specific transition for each metabolite was used for quantitation. The area under the curve of each EIC was normalized to the EIC of the internal standard and the ratio was used for relative comparisons.

RESULTS

ICH mouse model

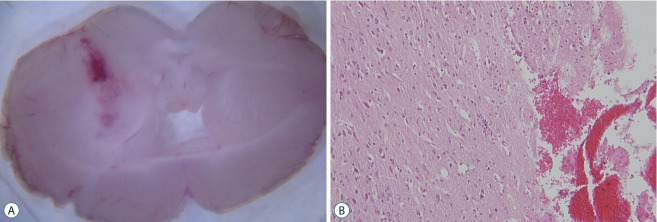

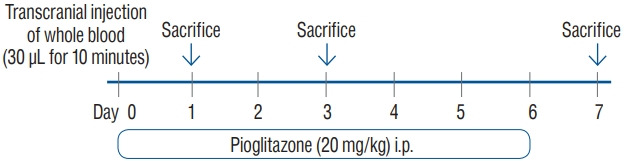

We established an ICH mouse model through intracranial injection of autologous whole blood (30 µL) (Fig. 1). A total of 30 mice were randomly assigned into the control and treatment groups. Mice in the treatment group were administered pioglitazone i.p. (20 mg/kg) for 1, 3, and 6 days. Mice in the control group were administered phosphate-buffered saline i.p. for 1, 3, and 6 days. The mice were sacrificed on days 1, 3, and 7 for analysis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Establishment of intracranial hemorrhage (IcH) models (hematoxylin and eosin, H&E). coronal section of the whole brain (A, scale bar=3 mm) and magnification of the hematoma (B, ×200).

Fig. 2.

Treatment schedule.

Pioglitazone administration reduces brain edema

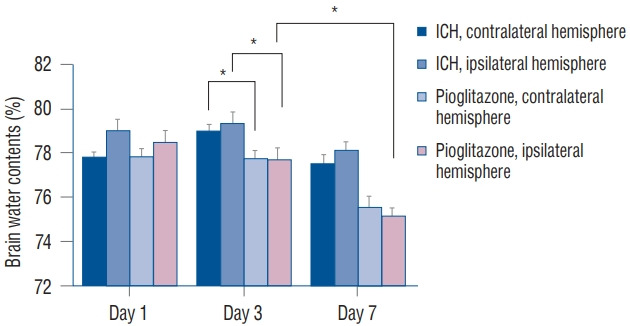

We compared the water contents of the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres in the ICH mice and ICH mice treated with pioglitazone. On day 3, brain edema in the ipsilateral hemispheres of mice treated with pioglitazone (77.69±0.50%) was decreased more than that of the ipsilateral hemispheres in the ICH mice (79.30±0.55%) (p=0.0001). The same finding was made in the contralateral hemispheres. On day 7, the brain edema in mice treated with pioglitazone was decreased more than that in the ICH mice. Brain edema in the ipsilateral hemispheres (75.11±0.35%) on day 7 was decreased more than that of the ipsilateral hemispheres (77.69±0.50%) on day 3 in the pioglitazone-treated group (p<0.0001) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

comparison of brain water contents. The water contents of both hemispheres in IcH mice treated with pioglitazone were lower than those in IcH mice on days 3 and 7. In the treatment group, the water content of the ipsilateral hemispheres on day 7 was decreased more than on day 3 (n = 7, each group). *p<0.05. IcH : intracranial hemorrhage.

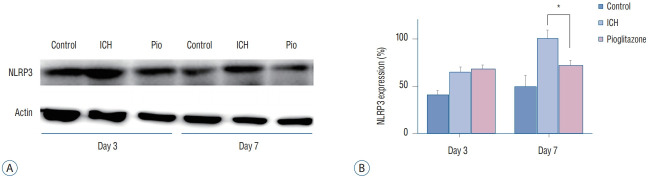

Pioglitazone administration reduces NLRP3

We compared the expression levels of NLRP3 in the ipsilateral hemispheres among the groups. The expression levels of NLRP3 in the ICH mice treated with pioglitazone were decreased more than those of the ICH mice on day 7 (p=0.025) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Western blot of NLRP3 in the control mice, IcH mice, and IcH mice treated with pioglitazone (A). The expression level of NLRP3 in the IcH mice treated with pioglitazone was decreased more than those in the IcH mice on day 7 (B). *p<0.05. IcH : intracranial hemorrhage.

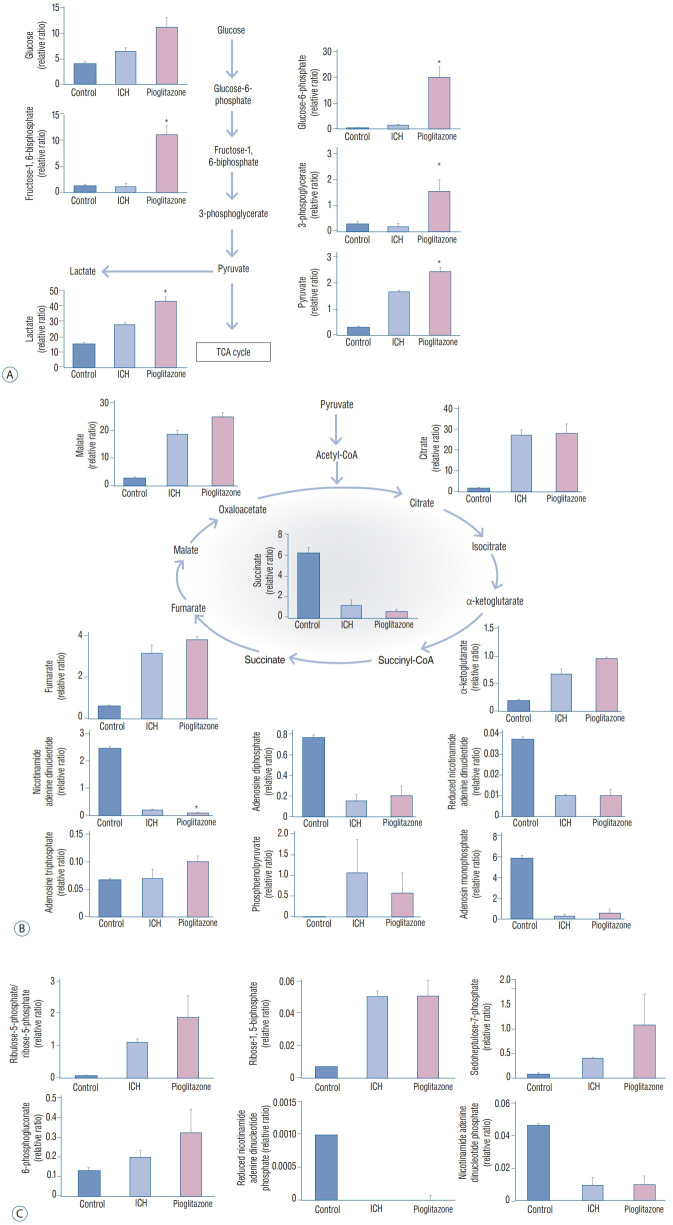

Pioglitazone administration modulates metabolism

Brain tissues were obtained from the control mice, ICH mice, and ICH mice treated with pioglitazone on day 7 and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. The values are calculated with an equation (peak area of analyte/peak area of internal standard).

Pioglitazone administration modulates metabolism

Increased glycolysis was observed in the brains of the ICH mice treated with pioglitazone for 6 days. Increased glucose availability was accompanied by an increase in glycolytic intermediates (glucose-6-phosphate, 19.76±4.17; fructose-1,6- biphosphate, 10.96±1.68; and pyruvate, 2.42±0.16) and increased lactate production (42.53±2.88) (Fig. 5A). Differences in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates (citrate, α-ketoglutarate, succinate, fumarate, and malate) were not significant between the ICH mice and the ICH mice treated with pioglitazone. Various metabolites, such as adenosine monophosphate, adenosine diphosphate, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), reduced NADH, and phosphoenolpyruvate, were investigated. The levels of NADH were lower in ICH mice treated with pioglitazone (0.07±0.02) than in the ICH mice (0.21±0.00). No differences in the other metabolites were noted (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis. In the glycolysis pathway, the production of glucose-6-phosphate, fructose-1,6- biphosphate, pyruvate, and lactate were increased in IcH mice brains treated with pioglitazone compared to those IcH mice (A). In the TcA cycle, the production of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide was decreased in IcH mice treated with pioglitazone more than that of IcH mice. Differences in other metabolites were not noted (B). In the PPP, there were no significant differences in PPP metabolites between the two groups (c). *p<0.05. IcH : intracranial hemorrhage, TcA : tricarboxylic acid, PPP : pentose phosphate pathway

We also investigated the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), including ribulose-5-phosphate/ribose-5-phosphate, ribose-1,5-bisphosphate, sedoheptulose-7-phosphate, 6-phosphogluconate, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), and reduced NADPH. There were no significant differences in the PPP metabolites between the ICH mice and ICH mice treated with pioglitazone (Fig. 5C).

DISCUSSION

We investigated pharmacological effects of pioglitazone on NLRP3 expression and perihematomal edema in an ICH mouse model. Pioglitazone is an agonist of the PPAR that regulates lipid metabolism and reduces insulin resistance [40]. PPAR is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily. It is expressed in monocytes, macrophages, and microglia. Recent studies have revealed that pioglitazone can reduce macrophage infiltration and the activation of tumor growth factor beta-1, leading to a deterioration in NLRP3 levels and downstream secretion of inflammatory cytokines [12,26]. Our results demonstrated that the brain swelling following ICH was less in mice treated with pioglitazone compared to ICH mice. The water content of the ICH hemispheres became greater as time passed. Pioglitazone administration reduced the water content in the ICH mice. The initial bleeding caused mechanical destruction of the brain’s cellular structure. Hematoma formation can compress the surrounding brain and increase intracranial pressure, thereby potentially affecting blood flow [18]. The therapeutic targets of ICH have focused on secondary brain injury because it is reversible. Secondary damage after ICH is caused by a cascade effect initiated by the primary injury (e.g., mechanical disruption and mass effect), the release of clotting components (e.g., hemoglobin and iron), and the biophysiological response to the hematoma (e.g., inflammation). A pronounced inflammatory response occurs with the activation of resident microglia, the influx of leukocytes into the brain, and the generation of inflammatory mediators [22,27,33]. The NLRP3 inflammasome can mediate perihematomal neuronal death. It occurs as early as three to six hours after a stroke, especially in ICH [10,44]. Inflammation and immunity have protentional roles in cerebral edema and NLRP3 is a well-known component of this cascade [37]. The NLRP3 inflammasome is associated with ICH-induced secondary injury. Inhibition of NLRP3 may affect the recovery of brain function after ICH [41]. We found that the NLRP3 was decreased in pioglitazone-treated ICH mice, suggesting that NLRP3 downregulation could reduce cerebral edema caused by ICH.

We observed that glucose uptake was converted into lactate through hyperglycolysis in the ICH model mice treated with pioglitazone. The levels of glycolytic metabolites were higher in ICH mice treated with pioglitazone than in the untreated ICH mice. Cerebral hyperglycolysis is thought to operate to cope with the extreme metabolic demand of the brain cells to restore homeostasis and integrity during recovery from ICH. Pioglitazone administration could compensate oxidative phosphorylation normally and meet an increased energy demand by an increased glycolysis.

Lactate is an important cerebral substrate of glucose. Neuroprotective effects and improvement in cognition following lactate administration have been reported in a traumatic brain injury model [25]. Other reports have revealed reductions in lesion sizes in both stroke and traumatic brain injury (TBI) animal models by lactate administration [2,6]. Lactate provides an energy source and is involved in cerebral metabolism in the glucose-deprived brain [11]. During neuronal glycolysis, lactate derived from astrocytes is produced at a faster rate, providing a quick and readily available source to meet increasing energy requirements [7,30]. Lactate-to-pyruvate ratio (LPR) has been found to be an independent predictor of mortality and unfavorable outcome in the largest cohort of TBI patients monitored with microdialysis [35]. Lactate concentration is a highly sensitive indicator of upregulated glycolytic flux but pyruvate levels are necessary in order to differentiate whether the upregulation of the glycolytic flux is anaerobic or an indicator of an increased use of the glycolysis under aerobic conditions. An increased levels of lactate and a high LPR have been highly sensitive predictors of poor outcomes [29]. Microdialysis can allow for the direct assessment of brain energetic metabolism after ICH. In one study, the effects of pioglitazone on glucose metabolism were investigated in cultured rat neurons and astroglia. Pioglitazone improved aerobic glycolysis and lactate release in the astroglia. These results revealed that pioglitazone may increase the efficiency of glucose metabolism in the damaged brain [16]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report showing that pioglitazone administration can increase levels of pyruvate and lactate in mice brains with ICH. Our results suggest that the production of lactate could supply the energy needs in ICH settings.

TCA cycle not only provides reducing equivalents of the respiratory complexes, it also generates high-energy phosphates. In the presence of oxygen, NADH are oxidized, leading to the development of an electrochemical gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane. This electrochemical gradient is utilized by ATP synthase to make ATP. During anoxia, NADH cannot be oxidized by the respiratory complexes; therefore, oxidative phosphorylation ceases [8]. PPP, which produces ribose5-phosphate and NADPH for DNA/RNA and fatty acid synthesis, is an alternative anabolic pathway to the preparatory phase of glycolysis. PPP are highly activated under normoxic conditions, whereas acute hypoxia causes downregulation of PPP metabolites concomitant with upregulation of glycolysis [36]. ATP is increased in the ICH mice treated with pioglitazone, compared with the ICH mice. However, the difference was not statistically significant between them. Although neither the intermediates of the TCA cycle nor the PPP metabolites were affected by pioglitazone administration, the level of NAD decreased. Cellular NAD was shown to be significantly depleted during reperfusion injury after ischemia [5,14].Also, exogenous NAD supplementation can increase intracellular NAD levels and reduce reperfusion-induced cell death in primary neuron cultures1, [42]. NAD is effective only when it is given within two hours after reperfusion [13]. We removed the ICH brains seven days after the injection of autologous blood for metabolomics analysis. Further study is needed to evaluate the changes in metabolites from the hyperacute stage to the late stage and define the therapeutic window of pioglitazone.

CONCLUSION

In summary, pioglitazone decreased NLRP3-related brain edema and increased anaerobic glycolysis, resulting in the production of lactate in an ICH mouse model. NLRP3 might be a therapeutic target for ICH recovery. The current study suggests that administration of pioglitazone could be an effective strategy for hemorrhagic stroke.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF)-2016R1D1A1A02937141. The author would like to acknowledge financial support from St. Vincent’ s Hospital Research Institute of Medical Science (SVHR-2017- 03).

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

INFORMED CONSENT

This type of study does not require informed consent.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization : JHS, SHY

Data curation : HK, JEL, HJY

Formal analysis : HK, SHY

Funding acquisition : SHY

Methodology : JEL, HJY

Project administration : JEL

Writing – original draft : HK, JEL

Writing – review & editing : HJY, JHS, SHY

References

- 1.Alano CC, Garnier P, Ying W, Higashi Y, Kauppinen TM, Swanson RA. NAD+ depletion is necessary and sufficient for poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1-mediated neuronal death. J Neurosci. 2010;30:2967–2978. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5552-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alessandri B, Schwandt E, Kamada Y, Nagata M, Heimann A, Kempski O. The neuroprotective effect of lactate is not due to improved glutamate uptake after controlled cortical impact in rats. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:2181–2191. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronowski J, Zhao X. Molecular pathophysiology of cerebral hemorrhage: secondary brain injury. Stroke. 2011;42:1781–1786. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.596718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Au A. Metabolomics and lipidomics of ischemic stroke. Adv Clin Chem. 2018;85:31–69. doi: 10.1016/bs.acc.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becatti M, Taddei N, Cecchi C, Nassi N, Nassi PA, Fiorillo C. SIRT1 modulates MAPK pathways in ischemic-reperfused cardiomyocytes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:2245–2260. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0925-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berthet C, Castillo X, Magistretti PJ, Hirt L. New evidence of neuroprotection by lactate after transient focal cerebral ischaemia: extended benefit after intracerebroventricular injection and efficacy of intravenous administration. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;34:329–335. doi: 10.1159/000343657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castro MA, Beltrán FA, Brauchi S, Concha II. A metabolic switch in brain: glucose and lactate metabolism modulation by ascorbic acid. J Neurochem. 2009;110:423–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chinopoulos C. Which way does the citric acid cycle turn during hypoxia? The critical role of α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex. J Neurosci Res. 2013;91:1030–1043. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esen F, Erdem T, Aktan D, Kalayci R, Cakar N, Kaya M, et al. Effects of magnesium administration on brain edema and blood-brain barrier breakdown after experimental traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2003;15:119–125. doi: 10.1097/00008506-200304000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fann DY, Lee SY, Manzanero S, Chunduri P, Sobey CG, Arumugam TV. Pathogenesis of acute stroke and the role of inflammasomes. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12:941–966. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallagher CN, Carpenter KL, Grice P, Howe DJ, Mason A, Timofeev I, et al. The human brain utilizes lactate via the tricarboxylic acid cycle: a 13C-labelled microdialysis and high-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance study. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 10):2839–2849. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helmy MM, Helmy MW, El-Mas MM. Additive renoprotection by pioglitazone and fenofibrate against inflammatory, oxidative and apoptotic manifestations of cisplatin nephrotoxicity: modulation by PPARs. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142303. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Q, Sun M, Li M, Zhang D, Han F, Wu JC, et al. Combination of NAD+ and NADPH offers greater neuroprotection in ischemic stroke models by relieving metabolic stress. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55:6063–6075. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0809-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu CP, Oka S, Shao D, Hariharan N, Sadoshima J. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase regulates cell survival through NAD+ synthesis in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2009;105:481–491. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.203703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irrera N, Pizzino G, Calò M, Pallio G, Mannino F, Famà F, et al. Lack of the Nlrp3 inflammasome improves mice recovery following traumatic brain injury. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:459. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Izawa Y, Takahashi S, Suzuki N. Pioglitazone enhances pyruvate and lactate oxidation in cultured neurons but not in cultured astroglia. Brain Res. 2009;1305:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katsuki H. Exploring neuroprotective drug therapies for intracerebral hemorrhage. J Pharmacol Sci. 2010;114:366–378. doi: 10.1254/jphs.10r05cr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keep RF, Hua Y, Xi G. Intracerebral haemorrhage: mechanisms of injury and therapeutic targets. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:720–731. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70104-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim SJ, Kim SH, Kim JH, Hwang S, Yoo HJ. Understanding metabolomics in biomedical research. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2016;31:7–16. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2016.31.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lebeaupin C, Proics E, de Bieville CH, Rousseau D, Bonnafous S, Patouraux S, et al. ER stress induces NLRP3 inflammasome activation and hepatocyte death. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1879. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, Yang J, Chen MH, Wang Q, Qin MJ, Zhang T, et al. Ilexgenin A inhibits endoplasmic reticulum stress and ameliorates endothelial dysfunction via suppression of TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome activation in an AMPK dependent manner. Pharmacol Res. 2015;99:101–115. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu A, Tang Y, Ran R, Ardizzone TL, Wagner KR, Sharp FR. Brain genomics of intracerebral hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:230–252. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayer SA, Rincon F. Treatment of intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:662–672. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ribo M, Grotta JC. Latest advances in intracerebral hemorrhage. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2006;6:17–22. doi: 10.1007/s11910-996-0004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rice AC, Zsoldos R, Chen T, Wilson MS, Alessandri B, Hamm RJ, et al. Lactate administration attenuates cognitive deficits following traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2002;928:156–159. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03299-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ricote M, Li AC, Willson TM, Kelly CJ, Glass CK. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ is a negative regulator of macrophage activation. Nature. 1998;391:79–82. doi: 10.1038/34178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rolland WB, 2nd, Manaenko A, Lekic T, Hasegawa Y, Ostrowski R, Tang J, et al. FTY720 is neuroprotective and improves functional outcomes after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2011;111:213–217. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0693-8_36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rynkowski MA, Kim GH, Komotar RJ, Otten ML, Ducruet AF, Zacharia BE, et al. A mouse model of intracerebral hemorrhage using autologous blood infusion. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:122–128. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sahuquillo J, Merino MA, Sánchez-Guerrero A, Arikan F, Vidal-Jorge M, Martínez-Valverde T, et al. Lactate and the lactate-to-pyruvate molar ratio cannot be used as independent biomarkers for monitoring brain energetic metabolism: a microdialysis study in patients with traumatic brain injuries. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sánchez-Abarca LI, Tabernero A, Medina JM. Oligodendrocytes use lactate as a source of energy and as a precursor of lipids. Glia. 2001;36:321–329. doi: 10.1002/glia.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schroder K, Zhou R, Tschopp J. The NLRP3 inflammasome: a sensor for metabolic danger? Science. 2010;327:296–300. doi: 10.1126/science.1184003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song N, Liu ZS, Xue W, Bai ZF, Wang QY, Dai J, et al. NLRP3 phosphorylation is an essential priming event for inflammasome activation. Mol Cell. 2017;68:185–197.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strbian D, Kovanen PT, Karjalainen-Lindsberg ML, Tatlisumak T, Lindsberg PJ. An emerging role of mast cells in cerebral ischemia and hemorrhage. Ann Med. 2009;41:438–450. doi: 10.1080/07853890902887303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stutz A, Kolbe CC, Stahl R, Horvath GL, Franklin BS, van Ray O, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome assembly is regulated by phosphorylation of the pyrin domain. J Exp Med. 2017;214:1725–1736. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Timofeev I, Carpenter KL, Nortje J, Al-Rawi PG, O’Connell MT, Czosnyka M, et al. Cerebral extracellular chemistry and outcome following traumatic brain injury: a microdialysis study of 223 patients. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 2):484–494. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J. Preclinical and clinical research on inflammation after intracerebral hemorrhage. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;92:463–477. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J, Doré S. Inflammation after intracerebral hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:894–908. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang J, Song MY, Lee JY, Kwon KS, Park BH. The NLRP3 inflammasome is dispensable for ER stress-induced pancreatic β-cell damage in Akita mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;466:300–305. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, Yu B, Wang L, Yang M, Xia Z, Wei W, et al. Pioglitazone ameliorates glomerular NLRP3 inflammasome activation in apolipoprotein E knockout mice with diabetes mellitus. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao ST, Cao F, Chen JL, Chen W, Fan RM, Li G, et al. NLRP3 is required for complement-mediated caspase-1 and IL-1beta activation in ICH. J Mol Neurosci. 2017;61:385–395. doi: 10.1007/s12031-016-0874-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ying W, Wei G, Wang D, Wang Q, Tang X, Shi J, et al. Intranasal administration with NAD+ profoundly decreases brain injury in a rat model of transient focal ischemia. Front Biosci. 2007;12:2728–2734. doi: 10.2741/2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao Y, Li Q, Zhao W, Li J, Sun Y, Liu K, et al. Astragaloside IV and cycloastragenol are equally effective in inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the endothelium. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;169:210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu X, Tao L, Tejima-Mandeville E, Qiu J, Park J, Garber K, et al. Plasmalemma permeability and necrotic cell death phenotypes after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. Stroke. 2012;43:524–531. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.635672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]