Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that anti-oxidant and / or anti-inflammation drugs that suppress rod death in cyclic light-reared Pde6brd10 mice are also effective in dark-reared Pde6brd10 mice.

Methods

In untreated dark-reared Pde6brd10 mice at post-natal (P) days 23 to 24, we measured the outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness (histology) and dark-light thickness difference in external limiting membrane-retinal pigment epithelium (ELM-RPE) (optical coherence tomography [OCT]), retina layer oxidative stress (QUEnch-assiSTed [QUEST] magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]); and microglia/macrophage-driven inflammation (immunohistology). In dark-reared P50 Pde6brd10 mice, ONL thickness was measured (OCT) in groups given normal chow or chow admixed with methylene blue (MB) + Norgestrel (anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory), or MB or Norgestrel separately.

Results

P24 Pde6brd10 mice showed no significant dark-light ELM-RPE response in superior and inferior retina consistent with high cGMP levels. Norgestrel did not significantly suppress the oxidative stress of Pde6brd10 mice that is only found in superior central outer retina of males at P23. Overt rod degeneration with microglia/macrophage activation was observed but only in the far peripheral superior retina in male and female P23 Pde6brd10 mice. Significant rod protection was measured in female P50 Pde6brd10 mice given 5 mg/kg/day MB + Norgestrel diet; no significant benefit was seen with MB chow or Norgestrel chow alone, nor in similarly treated male mice.

Conclusions

In early rod degeneration in dark-reared Pde6brd10 mice, little evidence is found in central retina for spatial associations among biomarkers of the PDE6B mutation, oxidative stress, and rod death; neuroprotection at P50 was limited to a combination of anti-oxidant/anti-inflammation treatment in a sex-specific manner.

Keywords: magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), optical coherence tomography (OCT), oxidative stress, inflammation, photoreceptors, cGMP

A common, aggressive, and currently untreatable form of blindness in patients is autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa (RP), which includes a missense point mutation in exon 13 of the β‐subunit of the rod phototransduction cGMP phosphodiesterase gene (PDE6B, http://www.Sph.Uth.Tmc.Edu/retnet/).1 This mutation somehow causes rod degeneration that, in turn, triggers cone death and loss of daytime vision. Different mechanisms of degeneration in light and dark appear to be at play because cyclic light-reared mice with this mutation (Pde6brd10) show significantly faster progression of rod degeneration than in dark-reared Pde6brd10 mice.2,3 In light, it is commonly thought that sustained flow of cations through abnormally open cGMP-gated cyclic nucleotide channels (due to the PDE6B mutation) results in cellular calcium overload and activation of calcium-dependent calpain proteases.4–25 In addition, an associated persistent increase in mitochondrial respiration is thought to lead to oxidative stress and rod death.4–25 Intriguingly, rod oxidative stress has also been measured in vivo in dark-reared Pde6brd10 mice, which seems at odds with the above model because the PDE enzyme is normally inactive in the dark.13 Further, dark-reared male and female Pde6brd10 mice show different spatial and temporal retinal oxidative stress patterns that also appear unexplained in terms of the sex-independent PDE6B mutation.13

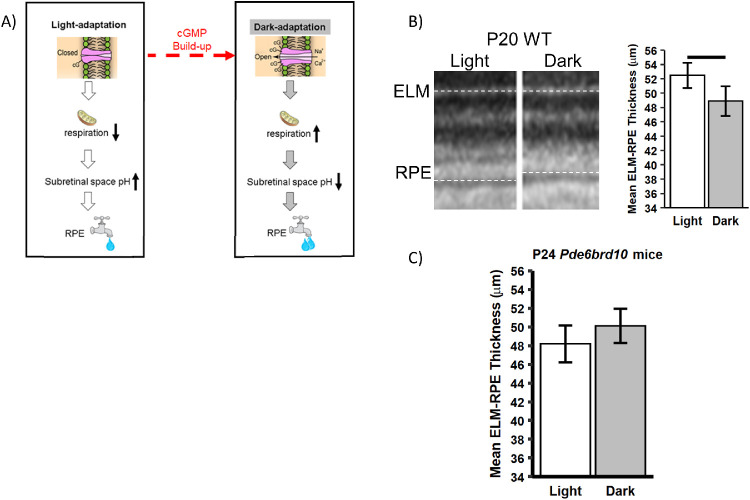

In this study, we test the hypotheses that (i) oxidative stress in vivo seen in dark-reared Pde6brd10 mice is spatially associated with an increase in inflammation and rod death, and (ii) that anti-oxidants and anti-inflammation approaches that promote survival in cyclic light-reared Pde6brd10 mice are similarly beneficial in dark-reared Pde6brd10 mice. To measure consequences of cGMP accumulation in Pde6brd10 mice, we evaluated the subretinal space thickness (i.e. external limiting membrane - retinal pigment epithelium thickness [ELM-RPE], a cGMP/mitochondria/pH/water efflux signaling pathway biomarker; Fig. 1). Oxidative stress was measured based on changes in the spin-lattice relaxation rate (1/T1, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) in mice given either saline or methylene blue (MB; QUEnch-assiSTed [QUEST] MRI).13,26,27 MB can act as an alternative electron transporter for mitochondria and oxidases leading to a reduction in the production of free radicals (i.e. an anti-oxidant effect).28–31 MB has also demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties.32,33 In addition, we tested Norgestrel, a synthetic progesterone, due to its ability to protect rods and cones from degeneration in cyclic light-reared Pde6brd10 mice, and its anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory properties.23,34–39

Figure 1.

ELM-RPE thickness is a biomarker of the cGMP / mitochondria / pH / water efflux signaling pathway. (A) Schematic proposing a cGMP / mitochondria / pH / water removal signaling pathway underlying changes ELM-RPE thickness in dark and light. In (B) representative light-dark OCT data are shown from a P20 WT mouse (left panel), with qualitative light-dark differences suggested by differences in ELM-RPE thickness indicated by dotted lines. A significant (P < 0.05) difference in ELM-RPE thickness was found, as expected (right panel). (C) In male P24 Pde6brd10 mice, a nonsignificant subretinal space photoresponse was found in superior and inferior retina. This result is consistent with abnormally high cGMP levels and open cyclic nucleotide gated channels that, as suggested by dotted line in A, are expected to lead to thinner ELM-RPE even in the light; more studies are needed in female P24 Pde6brd10 mice.

Materials and Methods

All mice were treated in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, and Institutional Animal and Care Use Committee authorization. Post-natal day (P)23, P24, or P50 Pde6brd10 mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were housed and maintained in full dark conditions (i.e. dark-reared). All mice were humanely euthanized by an overdose of urethane followed by a cervical dislocation, as detailed in our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC)-approved protocols. A group summary for the optical coherence tomography (OCT) and MRI studies of mice used in statistical analyses is presented in the Table.

Table.

Group Summary

| Strain | Examination Day | Lighting Condition | Treatment | Acute Injection | N | Gender | Examination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6J | P20 | Dark adapted then light | Untreated | 4 | M, F | OCT (ELM-RPE) |

|

| Pde6brd10 | P24 | Dark-reared then light | Untreated | Saline | 3 | M | OCT (ELM-RPE) |

| Pde6brd10 | P23 | Dark-reared | Untreated | MB | 7 | M | QUEST MRI |

| 6 | F | ||||||

| Norgestrel | MB | 5 | M | ||||

| 6 | F | ||||||

| Untreated | Saline | 5 | M | ||||

| 8 | F | ||||||

| Norgestrel | Saline | 6 | M | ||||

| 5 | F | ||||||

| Pde6brd10 | P50 | Dark-reared | Untreated | 10 | M | OCT (ONL) |

|

| 12 | F | ||||||

| N + 5MB | 5 | M | |||||

| 12 | F | ||||||

| 1MB | 9 | M | |||||

| 6 | F | ||||||

| 5MB | 8 | M | |||||

| 12 | F | ||||||

| Norgestrel | 6 | M | |||||

| 6 | F |

Optical Coherence Tomography

Groups

Post-natal (P) day 20 (P20) C57BL/6J wildtype (WT; male and female, n = 4) and dark-reared P24 Pde6brd10 (male, n =3) mice were each studied in a paired-design and examined with OCT (Envisu UHR2200) following previously published procedures.27,40 All mice were anesthetized in dark by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (6 mg/kg). Pupils were dilated with 1% tropicamide and 0.5% phenylephrine. The mouse eye was positioned with the optic nerve head (ONH) in the center of the OCT scan. Full field volume scans (1.4 mm × 1.4 mm at 1000 A-scan × 100 B-scan × 5) and a vertical B-scans (averaged 40 times) were collected. After imaging in the dark, mice were exposed to room light (approximately 500 lux) for > 5 hours, and OCT images were captured again in light Figure 1A presents the rationale for the dark-light ELM-RPE thickness differences in the two experimental groups described above and quantified in Figures 1B and C.

In addition, in a cross-sectional design, OCT images (Envisu VHR2200) were collected to help approximate the location of retinal layers for the dark-reared P23 transretinal profiles measured by MRI; only 1 to 2 images per group were needed for this task (not included in the Table because they were not used for statistical analyses). Cross-sectional studies were also performed using OCT images collected to quantitatively measure neuroprotection of various treatments at P50 as follows. Different groups from at least two litters of dark-reared P50 Pde6brd10 mice are summarized in the Table and were either untreated or started an admix chow at P10 containing approximately 80 mg/kg Norgestrel + approximately 5 mg/kg/day MB (N5MB), approximately 1 mg/kg/day (1 MB) or 5 mg/kg/day MB (5 MB), or approximately 80 mg/kg Norgestrel (anti-inflammatory, N).37 In these OCT studies, mice were anesthetized with urethane (36% solution intraperitoneally; 0.083 mL/20 g animal weight, prepared fresh weekly; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). 1% atropine sulfate was used to dilate the iris, and Systane Ultra was used to lubricate the eyes. Vertical B scan OCT were collected to identify central retinal layers that contribute to the superior-inferior MRI profile data because aligning the vitreous-retina (0% depth) and retina-choroid (100% depth) borders of OCT and MRI images reasonably matches structure with function.41

OCT analysis

The layer thicknesses were measured using in-house developed R scripts that objectively identify layer boundaries after searching the space provided by a hand-drawn estimate (“seed boundaries”). Central retina regions ± 350 to 630 µm were statistically analyzed (see below).

Histology

From representative litters for each group (i.e. dark-reared P23 (WT or Pde6brd10 mice), whole eyes were fixed at room temperature in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 1.5 hours. Frozen sections (15 µm) were collected on Superfrost glass slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Frozen sections were blocked and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 5% donkey serum in 1 times PBS for 30 minutes and incubated with primary antibody (rat anti-mouse CD68, 1:500, AbD Serotoc; rabbit anti-mouse Iba1, 1:500; Wako) diluted in 5% donkey serum overnight at 48°C. Following washes, sections were incubated with secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor donkey anti-mouse/rabbit/goat with either a 488 or 594 fluorescent probe; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) and Hoechst 33342 nuclear stain (1:10,000; Thermo Fisher Scientific) 2 hours at room temperature. Eliminating the primary antibody in solution served as a negative control. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst. Sections were mounted using Mowiol (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.) with Dabco antifade agent (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.). They were viewed using a Leica DM LB2 microscope with Nikon Digital Sight DS-U2 camera (Kanagawa, Japan), using ×10 and ×40 objectives. Images were taken using the software NIS-Elements version 3.0 (Nikon). Samples were processed at the same time using the same buffers and antibody solutions. Identical microscope settings were used when imaging each preparation. Details regarding other antibodies are presented elsewhere.34 Quantification of ONL thickness (Hoechst staining) was carried out using ImageJ software. ONL thickness was measured by taking three spatially distinct measurements in each of the four regions, per section. Sex was not included in analyses because we did not have sufficient replication to examine sex differences. In addition, visual inspection of histology sections and MRI data did not suggest overt differences between sexes.

QUEST MRI

Groups

In a cross-sectional design, T1 data sets were collected from male and female P23 Pde6brd10 mice treated with approximately 80 mg/kg Norgestrel started at P10; these data were compared to previously collected data from untreated groups.13,37 As summarized in the Table, 24 hours prior to MRI study all mice were given a single dose of 1 mg/kg MB i.p., dissolved in saline, or an equal volume of just saline.

High-resolution T1 MRI data sets were acquired on a 7T system (Bruker ClinScan, Billerica, MA, USA) using a receive-only surface coil (1.0 cm diameter) centered on the left eye. Mice were kept in the dark throughout the preparation and MRI examination. In all groups, immediately before the MRI experiment, animals were anesthetized with urethane (36% solution given intraperitoneally; 0.083 mL / 20 g animal weight, prepared fresh daily; Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and treated topically with 1% atropine to ensure dilation of the iris during light exposure followed by 3.5% lidocaine gel to reduce eye motion. MRI data were acquired using several single spin-echo sequences (time to echo 13 ms, 7 × 7 mm2, matrix size 160 × 320, and slice thickness 600 µm). Images were acquired at different repetition times (TRs) in the following order (number per time between repetitions in parentheses): TR 0.15 seconds (6), 3.50 seconds (1), 1.00 seconds (2), 1.90 seconds (1), 0.35 seconds (4), 2.70 seconds (1), 0.25 seconds (5), and 0.50 seconds (3). To compensate for reduced signal–noise ratios at shorter TRs, progressively more images were collected as the TR decreased. The present resolution in the central retina is sufficient for extracting meaningful layer-specific anatomic and functional data, as previously discussed.42

MRI Data Analysis

For QUEST data, each T1 data set of 23 images was first processed by registering (rigid body; STACKREG plugin, ImageJ, Rasband, W.S., ImageJ, U. S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/, 1997–2016) and then averaging images with the same TRs in order to generate a stack of 8 images. These averaged images were then registered (rigid body) across TRs. QUEST data were corrected for imperfect slice profile bias in the estimate of T1, as previously described (Chapter 18 in Ref. 43). Briefly, by normalizing to the shorter TR, some of the bias can be reduced, giving a more precise estimate for T1. To achieve this normalization, we first apply a 3 × 3 Gaussian smoothing (performed three times) on only the TR 150 ms image to minimize noise and emphasize signal. The smoothed TR 150 ms image was then divided into the rest of the images in that T1 data set. Preliminary experiments (not shown) found that this procedure helps to minimize day-to-day variation in the 1/T1 profile previously noted and obviated the need for a “vanilla control” group used previously for correcting for day-to-day variations.44,45 The 1/T1 maps were calculated using the seven normalized images via fitting to a three-parameter T1 equation (y = a + b*(exp(-c*TR)), where a, b, and c are fitted parameters) on a pixel-by-pixel basis using R (version 2.9.0; R Development Core Team [2009]). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. ISBN 3–900051–07–0) scripts developed in-house, and the minpack.lm package (version 1.1.1, Timur V. Elzhov and Katharine M. Mullen minpack.lm: R interface to the Levenberg-Marquardt nonlinear least-squares algorithm found in MINPACK; R package version 1.1–1).

In each mouse, whole retinal thicknesses (µm) were objectively determined using the “half-height method” wherein a border is determined via a computer algorithm based on the crossing point at the midpoint between the local minimum and maximum, as detailed elsewhere.46,47 The distance between two neighboring crossing-points thus represents an objectively defined retinal thickness. The 1/T1 profiles in each mouse were then normalized with 0% depth at the presumptive vitreoretinal border and 100% depth at the presumptive retina-choroid border. The present resolution is sufficient for extracting meaningful layer-specific anatomic and functional data, as previously discussed.48,49

We compared superior and inferior profiles from ± 400 to 1400 µm (central retina) from the ONH generated for each animal group. Excessive and asynchronous production of paramagnetic free radicals in retinal laminae is measured based on a reduction in 1/T1 with MB (i.e. a positive QUEST MRI response).27

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean and 95% confidence intervals. A significance level of 0.05 was used for most tests, with interactions being tested using a significance level of 0.10 due to these tests having less power.

General Modeling Strategy

We used the same modeling strategy for both 1/T1 and thickness for OCT data. All mice for a given outcome for a given mouse age were analyzed with a single statistical model that accounted for experimental factors, such as MB treatment, chow, gender, and mouse. The factors included in each model are detailed below. Each outcome was analyzed using linear mixed models with the Kenward-Roger method for calculating degrees of freedom using Proc Mixed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Software, Cary, NC, USA) because both outcomes had repeated measures for each mouse. We used restricted cubic splines to model and compare mouse-specific profiles between groups. This method fits separate cubic regressions within a set number of “windows,” with the boundaries of the windows determined by knot locations, and the lines in adjacent windows constrained to be continuous across the windows. The number of windows with a relationship between outcome and location (i.e. knots) was initially evaluated separately for each group for any given analysis, and the Akaike and Schwarz Bayesian information criteria (AIC and BIC) were used to identify the model with the fewest knots needed to model all groups. The model used to select the number of knots included all fixed effects specific to a given experiment as well as a random intercept for mouse nested within the group. Additional random coefficients were added based on a decrease in AIC and BIC. Given the random spline coefficients included in all models, we used an unstructured covariance matrix for the random coefficients to account for associations in spline coefficients due to subject-specific profiles. For laminae thickness based on OCT, we used linear contrasts to estimate and compare means integrated across the entire layer.

ELM-RPE Thickness for P24 Pde6brd10 Mice

We analyzed paired dark-light ELM-RPE thickness data (OCT) of P24 Pde6brd10 mice separately for superior/inferior regions relative to the ONH. The model for each side of the ONH included the fixed effects of light/dark, eye, depth location for the spline coefficients, and all interactions among these fixed effects. The model for data inferior to the ONH was adequately modeled with a minimum of 9 knots, whereas the model for data superior to the ONH required 10 knots (see above for criteria). The models for both sides included random coefficients for the intercept, eye, light, and the seventh knot location for mouse nested within MB treatment/gender. OCT results are limited to the left eye, the same side studied by QUEST MRI.

QUEST MRI

The model for analyzing cross-sectional 1/T1 data collected from the left eye included the fixed effects of diet, MB treatment, gender, side of the ONH, and for the six locations for the spline coefficients. This model also included random coefficients for the intercept, side of the ONH, MB treatment, knot locations 1, 3, and 4, as well as interactions between side of the ONH and knot locations for mouse nested within diet, MB treatment, and gender. Mean profiles were estimated and compared using contrasts for the depths measured.

Histology-Based ONL Thickness

We used a linear mixed model to analyze the histological data of P23 WT and Pde6brd10 mice because each section had three spatially distinct measurements for each side/region. The model we used included strain (WT versus Pde6brd10), side (inferior versus superior), region (central versus peripheral), and all interactions as fixed effects. This model also included random coefficients for intercept, side, region, and the side/region interaction for mouse nested within strain. As with the analyses described above, we used the Kenward-Roger method to calculate degrees of freedom. Side/region-dependent strain differences were examined because the three-way interaction was significant.

ONL Thickness for P50 Pde6brd10 Mice

We analyzed cross-sectional ONL thickness data of P50 Pde6brd10 mice using a model that included chow, gender, side of the ONH, and eight knot locations for the spline coefficients. This model also included random coefficients for the intercept, side of the ONH, and the sixth knot location for mouse nested within chow and gender.

Results

PDE6B Mutation Suppressed the Dark Versus Light ELM-RPE Thickness Difference as Shown In Vivo by OCT

Previous quantitative studies performed in P40 or older WT C57BL/6J mice indicate a cGMP / mitochondria / pH / water removal signaling pathway that causes ELM-RPE to be measurably thinner in the dark than in the light; this phenotype is apparent in a representative P20 WT C57BL/6J mouse, which also demonstrates a clear dark less than light ELM-RPE thickness difference, as shown in Figure 1B.40,41,49–56 In contrast, male P24 Pde6brd10 mice lack a statistically significant dark-light ELM-RPE difference (inferior = ‒1.31; 95% confidence interval [CI] = ‒3.29 to 0.66; superior = ‒2.53, 95% CI = ‒5.56 to 0.49; P > 0.05 for both), consistent with a panretinal PDE6B mutation-induced increase in cGMP levels in the light (see Fig. 1C). These quantitative results from dark-reared P24 mice are similar to the small dark-light ELM-RPE thickness differences reported in cyclic-light reared Pde6brd10 mice.50

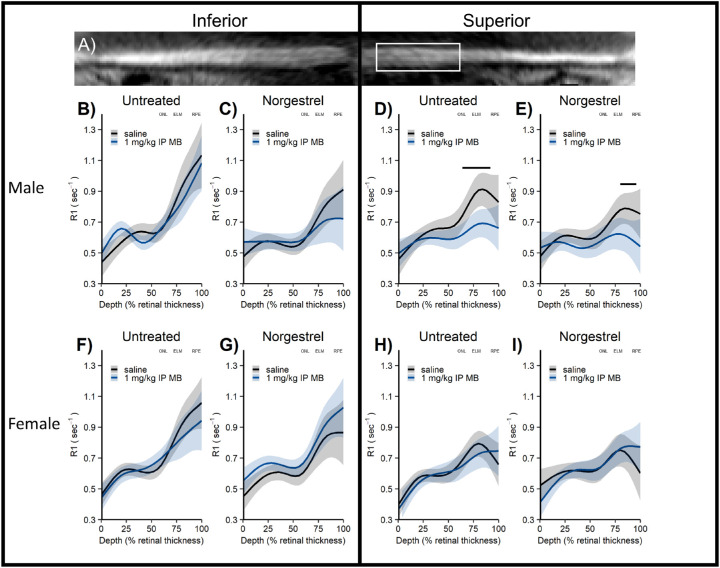

Central Retina Oxidative Stress Measured With QUEST MRI in Norgestrel-Treated P23 Dark-Reared Pde6brd10 Mice

As shown in Figure 2, Norgestrel-treated P23 dark-reared male Pde6brd10 mice had significantly lower 1/T1 values after MB administration, localized to the superior outer central retina (P < 0.05), compared to the saline group, a pattern indicative of on-going oxidative stress, this quantitative extent and spatial mapping of oxidative stress was not significantly (P > 0.05) different from our previous reported extent and spatial map of oxidative stress in untreated P23 dark-reared Pde6brd10 male mice.13 In contrast, neither our previous report in untreated nor the present Norgestrel-treated P23 dark-reared Pde6brd10 female mice showed such evidence of oxidative stress.13,23,34,37

Figure 2.

Central retina oxidative stress measured with QUEST MRI in Norgestrel-treated P23 dark-reared Pde6brd10 mice. (A) Representative flattened MRI image showing thinner superior retina in far periphery; white box indicates retina regions analyzed (± 400 – 1400 µm from ON although only superior region-of-interest shown for clarity). (B – E) Male P23 Pde6brd10 mice show in vivo oxidative stress limited to superior outer retina (untreated QUEST MRI); this finding is unmodified by Norgestrel (Norgestrel treated QUEST MRI) and there is little evidence for microglia activation (Iba-1 staining) in central retina. (F – I) Female P23 Pde6brd10 mice do not show evidence of oxidative stress (untreated QUEST MRI; Norgestrel treated QUEST MRI). To help spatially orient the MRI data, approximate location of outer nuclear layer (ONL), external limiting membrane (ELM), and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) are noted based on representative OCT images from age, side, and sex appropriate untreated Pde6brd10 mice (OCT data not shown for clarity).

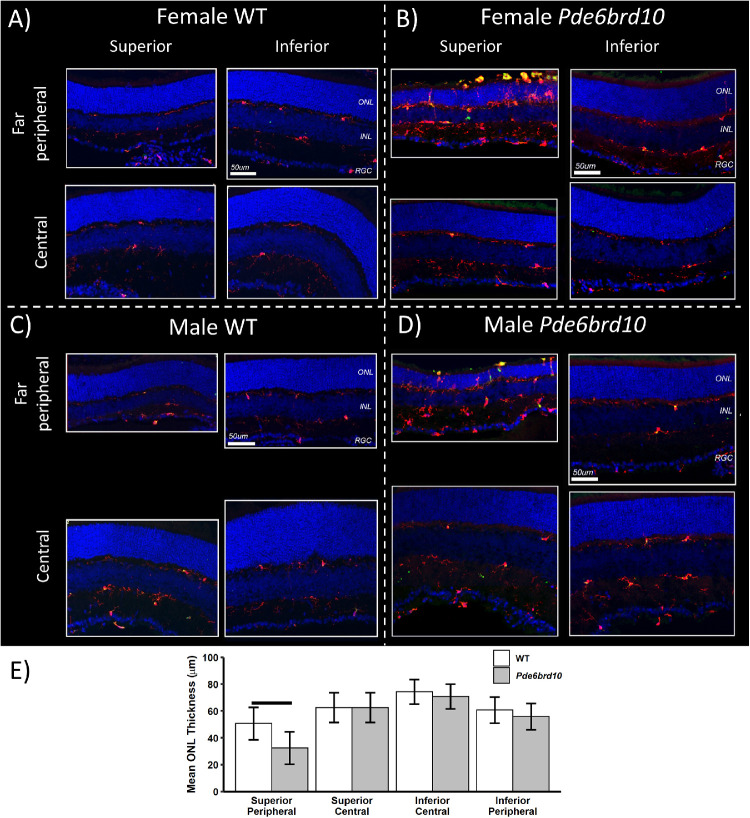

Immunohistology of P23 Dark-Reared Pde6brd10 Mice

We asked if the sex-dependent central retina regions of oxidative stress identified in P23 dark-reared Pde6brd10 mice (see Fig. 2) were spatially associated with regions of inflammation as indicated by the presence of activated microglia and / or macrophages. To this end, we mapped microglia / macrophage activation through visualization of Iba1 and CD68, as conducted in previous studies.37,57 Iba-1 is a pan microglia marker and CD68 a marker for phagocytic monocytes. As shown in Figure 3, microglia/macrophages in the central superior regions of dark-reared P23 male or female mice were predominantly localized to the plexiform layers with low levels of CD68 immunoreactivity; all indicative features of a normal state.58 Thus, no visible evidence is found for inflammation in central superior regions of dark-reared P23 male or female mice.

Figure 3.

Immunohistology of P23 dark-reared Pde6brd10 mice. At P23, representative immunohistology from male and female mice age-matched control dark-reared male and female mice are shown in (A and C), and from Pde6brd10 mice in (B and D). Microglia/macrophage activation (Iba1, CD68 staining), and rod degeneration (ONL thinning) were localized to far peripheral superior; a similar pattern of atrophy can be visually appreciated in Figure 2A. Iba-1 staining (red), CD68 staining (green), and yellowing staining representing both Iba-1 and CD68 staining in each of the 4 panels; Hoechst staining for nuclei (blue) is also presented. Quantification of ONL thickness in the various regions shown in (E) indicates a statistically significantly thinner ONL limited to the peripheral superior retina compared with inferior retina; n = 4 mice per group, horizontal bar P < 0.001.

Evidence for Superior Greater Than Inferior ONL Thinning in Dark-Reared Pde6brd10 Mice

In male and female P23 dark-reared Pde6brd10 versus WT mice, visual inspection of histologic data (see Fig. 3) suggested more extensive far peripheral rod loss (thinning of the ONL) than in central retina, and signs of accompanying inflammation in superior versus inferior retina. The latter was evident by greater numbers of microglia (Iba-1 staining) and CD68-positivity. Along with localization of microglia/macrophages in the ONL rather than in plexiform layers, these observations are indicative of retinal inflammation.37,57,59 Unfortunately, software limitations prevented quantitative measurements of oxidative stress in far peripheral retina. Quantification of ONL thickness in retinal sections revealed a statistically significantly thinner ONL in the Pde6brd10 mice peripheral superior retina compared with WT mice (see Fig. 3). In addition, localized rod death to superior far peripheral retina can also be appreciated visually in vivo on, for example, representative flattened MRI from male (see Fig. 2A) and female (not shown) Pde6brd10 mice; OCT was not performed in enough mice at this time point for statistical comparisons. However, a significant (P < 0.0001) difference in P50 Pdeb6rd10 mice ONL thicknesses between superior and inferior central retina is detected using OCT data (superior mean thickness = 30.22 µm; 95% CI = 29.45 µm to 30.99 µm; inferior mean thickness = 35.91 µm; 95% CI = 35.00 µm to 36.83 µm); the side difference did not depend on any combination of “chow” groups (including normal chow) and gender (P > 0.05).

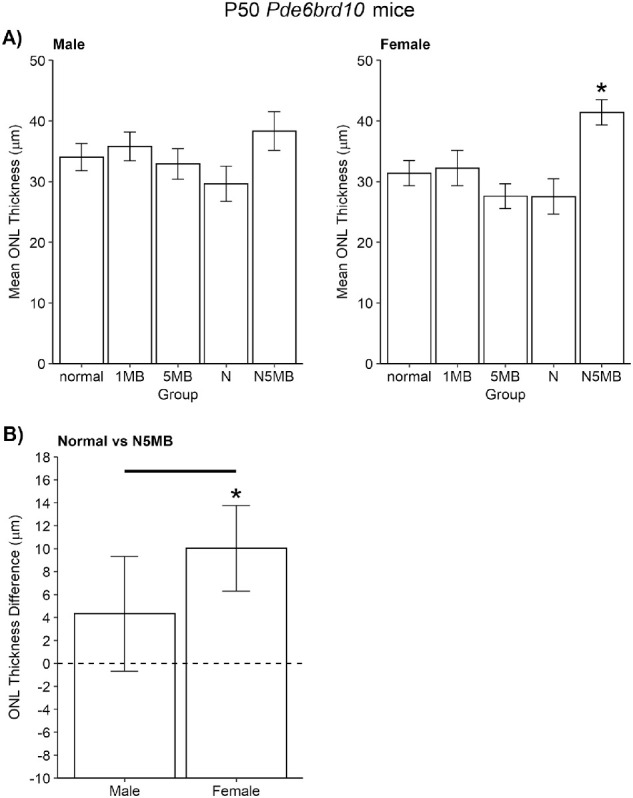

Central Retina Rod Neuroprotection is Possible in Dark-Reared Pde6brd10 Mice

Among all treatment groups, only a 5 mg/kg/day MB + Norgestrel diet in female P50 dark-reared Pde6brd10 mice showed significant (P < 0.05) improvement of the central ONL thickness (independent of side, average results are shown) as quantitatively measured from OCT data compared to that in the untreated group (Fig. 4A). Male P50 dark-reared Pde6brd10 mice on a 5 mg/kg/day MB + Norgestrel diet did not show a significant improvement of central ONL thickness (Fig. 4B; P > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Central retina rod neuroprotection is possible in dark-reared Pde6brd10 mice. (A) At P50, central rod protection (averaged from inferior and superior retina) was observed in female (and not male) Pde6brd10 mice given approximately 80 mg/kg Norgestrel + 5 mg/kg/day MB (N5MB) diet. Other groups are: untreated mice, approximately 1 mg/kg/day MB (1MB), approximately 5 mg/kg/day MB (5MB), approximately 80 mg/kg/day Norgestrel (N). (B) Further analysis finds that the difference between mice fed normal chow versus N5MB chow was significant between male and female P50 dark-reared Pde6brd10 mice (horizontal line); in male mice this difference was not statistically distinguishable from zero, whereas it was in female mice (star). Together, these results show that the greatest impact on rod survival by N5MB chow is found in P50 dark-reared female Pde6brd10 mice.

Discussion

In this study, we find little evidence for coherent spatial associations in the central retina between biomarkers of the PDE6B mutation (observed in superior and inferior central retina, OCT; see Fig. 1), oxidative stress (observed only in the superior central retina of male mice, QUEST MRI; see Fig. 2), rod death and inflammation (not evident in the central retina of male and female mice histology; see Fig. 3). These results appear in contrast to studies of central rod death in cyclic light-reared Pde6brd10 mice that suggest contributions from oxidative stress and inflammation; the latter conclusions are based in part on beneficial responses to, for example, treatment by Norgestrel, a drug with anti-oxidant and anti-inflammation properties.17,23,34–37,60–68 However, few studies have investigated whether similar mechanisms are at play in the degeneration of rods in the central retina of dark-reared and in cyclic light-reared Pde6brd10 mice. In support of the “snap-shot-in-time” data herein, chronic treatment with either MB or Norgestrel, drugs with anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, did not rescue rod degeneration at P50 in dark-reared mice (see Fig. 4).23,33,35,37 These results, together with the fact that dark-rearing significantly slows the rate of central rod loss compared to cyclic light-rearing in C57BL/6J Pde6brd10 mice, further support the possibility that distinct mechanisms are responsible for rod degeneration in central retina in Pde6brd10 mice during dark- and cyclic light-rearing conditions.17,23,34−37,60−67

In this study, we show for the first time that rod rescue is possible in dark-reared Pde6brd10 mice. The benefit came from combining MB and Norgestrel, and, intriguingly, was significant in dark-reared female, but not male, Pde6brd10 mice (see Fig. 4). In cyclic-light reared Pde6brd10 mice, the same genetic mutation is reported to be processed in a sex-specific manner.69 More work is needed to identify why the N5MB drug combination appears sex-specific. In addition, the present results are reminiscent of a prior study that found the need for a multi-pronged approach to protect cone photoreceptors in cyclic light-reared Pde6brd10 mice.64 However, it is difficult to speculate on how there may have been a synergistic effect because MB and Norgestrel have pleiotropic actions on pro-oxidant and pro-inflammatory pathways. In any event, the present results suggest the use of drug cocktails to mitigate photoreceptor degeneration in both daytime and night-time conditions; additional studies are needed to determine if drug combinations also need to be sex-specific.

One potential limitation of the present study is that rod photoreceptor cells of C57BL/6J Pde6brd10 mice from Jackson Laboratory carry two gene mutations: the missense point mutation in exon 13 of the β‐subunit of the rod phototransduction cGMP phosphodiesterase gene (PDE6B), and an underappreciated null mutation in mitochondria gene NAD nucleotide transhydrogenase (Nnt).53,70,71 This mutation increases vulnerability to oxidative stress and is a mutation not found in the general patient population.72 For comparison, we note that WT brown 129S6/ev mice, which do not have the Nnt mutation, have an 11% greater mitochondrial reserve than C57BL/6J mice from the Jackson Laboratory as measured by an ex vivo Seahorse assay and by our OCT studies.52,53 Further, this mutation likely affects rescue potential because sodium iodate produces less rod mitochondrial oxidative stress and rod death in 129S6/ev mice than in C57BL/6J mice.53,73 We anticipate future studies that address this potential problem by comparing Pde6brd10 mice on the C57BL/6J background with Pde6brd10 C57BL/6 mice from a different vendor without the Nnt mutation, or with Pde6brd10 mice on the 129S6/ev background.

In this study, overt rod atrophy appeared localized only to far peripheral superior retina in P23 dark-reared male and female Pde6brd10 mice and seems to spread to the central retina by P50. This apparent periphery-to-central degeneration pattern was an incidental outcome during the testing of our main hypothesis and is presented for completeness. Nonetheless, these data raise the surprising possibility that different mechanisms of rod atrophy are operant within different parts of the same retina of dark-reared Pde6brd10 mice. This speculation is in line with the hypothesis that an apparently homogeneous population of neurons (such as rod photoreceptors) can show meaningful within-type heterogeneity.74 Intriguingly, patients with RP lose vision in their peripheral superior hemifield, whereas that in the inferior visual field is relatively preserved. In contrast to the present results, cyclic light-reared Pde6brd10 mice show a center-to-periphery rod death pattern with similar degrees of loss in superior and inferior retina; the present data suggest that this pattern may be different with dark-rearing.14,75 More work, such as experiments that challenge the difference in sensitivity of the superior versus inferior with a focused light source, is needed to quantitatively study this apparent asymmetrical pattern and to determine why it occurs in dark-rearing but not cyclic light-reared Pde6brd10 mice.76,77

In summary, the results of this study do not support our hypothesis that anti-oxidant and / or anti-inflammation drugs that suppress rod death in cyclic light-reared Pde6brd10 mice are also effective in dark-reared Pde6brd10 mice. Dark-reared P50 Pde6brd10 mice showed a rod death spatial pattern that was different than that reported for cyclic light-reared Pde6brd10 mice, and neuroprotection limited to a combination of anti-oxidant / anti-inflammation treatment in a sex-specific manner.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (RO1 EY026584 to B.A.B.) and R01 AG058171 to B.A.B.), NIH intramural Research Programs EY000503 and EY000530 to H.Q., NEI Core Grant P30 EY04068, Science Foundation Ireland (T.C.), and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (Kresge Eye Institute, B.A.B.).

Disclosure: B.A. Berkowitz, None; R.H. Podolsky, None; K.L. Childers, None; S.L. Roche, None; T.G. Cotter, None; E. Graffice, None; L. Harp, None; K. Sinan, None; A.M. Berri, None; M. Schneider, None; H. Qian, None; S. Gao, None; R. Roberts, None

References

- 1. Hartong DT, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet. 2006; 368: 1795–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chang B, Hawes NL, Pardue MT, et al.. Two mouse retinal degenerations caused by missense mutations in the beta-subunit of rod cGMP phosphodiesterase gene. Vision Res. 2007; 47: 624–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cronin T, Lyubarsky A, Bennett J. Dark-rearing the rd10 mouse: implications for therapy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012; 723: 129–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berkowitz BA, Podolsky RH, Farrell B, et al.. D-cis-diltiazem can produce oxidative stress in healthy depolarized rods in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018; 59: 2999–3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fox DA, Poblenz AT, He L, Harris JB, Medrano CJ. Pharmacological strategies to block rod photoreceptor apoptosis caused by calcium overload: a mechanistic target-site approach to neuroprotection. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2003; 13(suppl 3): S44–S56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berkowitz BA, Gradianu M, Schafer S, et al.. Ionic dysregulatory phenotyping of pathologic retinal thinning with manganese-enhanced MRI. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008; 49: 3178–3184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nakazawa M. Effects of calcium ion, calpains, and calcium channel blockers on retinitis pigmentosa. J Ophthalmol. 2011; 2011: 292040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Takano Y, Ohguro H, Dezawa M, et al.. Study of drug effects of calcium channel blockers on retinal degeneration of RD mouse. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004; 313: 1015–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sato M, Ohguro H, Ohguro I, et al.. Study of pharmacological effects of nilvadipine on RCS rat retinal degeneration by microarray analysis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003; 306: 826–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yamazaki H, Ohguro H, Maeda T, et al.. Preservation of retinal morphology and functions in royal college surgeons rat by nilvadipine, a Ca(2+) antagonist. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002; 43: 919–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barabas P, Cutler PC, Krizaj D. Do calcium channel blockers rescue dying photoreceptors in the Pde6b (RD1) mouse? Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010; 664: 491–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Allocca M, Manfredi A, Iodice C, Di Vicino U, Auricchio A. AAV-mediated gene replacement, either alone or in combination with physical and pharmacological agents, results in partial and transient protection from photoreceptor degeneration associated with betaPDE deficiency. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 5713–5719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Berkowitz BA, Podolsky RH, Berri AM, et al.. Dark rearing does not prevent rod oxidative stress in vivo in Pde6brd10 mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018; 59: 1659–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang T, Reingruber J, Woodruff ML, et al.. The PDE6 mutation in the rd10 retinal degeneration mouse model causes protein mislocalization and instability and promotes cell death through increased ion influx. J Biol Chem. 2018; 293: 15332–15346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dong E, Bachleda A, Xiong Y, Osawa S, Weiss ER. Reduced phosphoCREB in Müller glia during retinal degeneration in rd10 mice. Molecular Vision. 2017; 23: 90–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fox DA, Poblenz AT, He L. Calcium overload triggers rod photoreceptor apoptotic cell death in chemical-induced and inherited retinal degenerations. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999; 893: 282–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kang K, Tarchick MJ, Yu X, Beight C, Bu P, Yu M. Carnosic acid slows photoreceptor degeneration in the Pde6b(rd10) mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. Sci Rep. 2016; 6: 22632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mitton KP, Guzman AE, Deshpande M, et al.. Different effects of valproic acid on photoreceptor loss in Rd1 and Rd10 retinal degeneration mice. Mol Vis. 2014; 20: 1527–1544. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rohrer B, Bandyopadhyay M, Beeson C. Reduced metabolic capacity in aged primary retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) is correlated with increased susceptibility to oxidative stress. In: Bowes Rickman C, LaVail MM, Anderson RE, Grimm C, Hollyfield J, Ash J (eds), Retinal Degenerative Diseases. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016: 793–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Perron NR, Beeson C, Rohrer B. Early alterations in mitochondrial reserve capacity; a means to predict subsequent photoreceptor cell death. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2013; 45: 101–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kooragayala K, Gotoh N, Cogliati T, et al.. Quantification of oxygen consumption in retina ex vivo demonstrates limited reserve capacity of photoreceptor mitochondria. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015; 56: 8428–8436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang X, Zhao L, Zhang Y, et al.. Tamoxifen provides structural and functional rescue in murine models of photoreceptor degeneration. J Neurosci. 2017; 37: 3294–3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Byrne AM, Ruiz-Lopez AM, Roche SL, Moloney JN, Wyse-Jackson AC, Cotter TG. The synthetic progestin norgestrel modulates Nrf2 signaling and acts as an antioxidant in a model of retinal degeneration. Redox Biol. 2016; 10: 128–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rodríguez-Muela N, Hernández-Pinto AM, Serrano-Puebla A, et al.. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization and autophagy blockade contribute to photoreceptor cell death in a mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. Cell Death Differ. 2015; 22: 476–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Power MJ, Rogerson LE, Schubert T, Berens P, Euler T, Paquet-Durand F. Systematic spatiotemporal mapping reveals divergent cell death pathways in three mouse models of hereditary retinal degeneration. J Comp Neurol. 2020; 528(7): 1113–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Berkowitz BA, Podolsky RH, Lins-Childers KM, Li Y, Qian H. Outer retinal oxidative stress measured in vivo using QUEnch-assiSTed (QUEST) OCT. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019; 60: 1566–1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Berkowitz BA. Oxidative stress measured in vivo without an exogenous contrast agent using QUEST MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2018; 291: 94–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Salaris SC, Babbs CF, Voorhees WD. Methylene blue as an inhibitor of superoxide generation by xanthine oxidase. Biochem Pharmacol. 1991; 42: 499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lin A-L, Poteet E, Du F, et al.. Methylene blue as a cerebral metabolic and hemodynamic enhancer. PLoS One. 2012; 7: e46585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang X, Rojas JC, Gonzalez-Lima F. Methylene blue prevents neurodegeneration caused by rotenone in the retina. Neurotox Res. 2006; 9: 47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Callaway NL, Riha PD, Bruchey AK, Munshi Z, Gonzalez-Lima F. Methylene blue improves brain oxidative metabolism and memory retention in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004; 77: 175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ahn H, Kang SG, Yoon SI, et al.. Methylene blue inhibits NLRP3, NLRC4, AIM2, and non-canonical inflammasome activation. Sci Rep. 2017; 7: 12409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lin Z-H, Wang S-Y, Chen L-L, et al.. Methylene blue mitigates acute neuroinflammation after spinal cord injury through inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation in microglia. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017; 11: 391–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Roche SL, Kutsyr O, Cuenca N, Cotter TG. Norgestrel, a progesterone analogue, promotes significant long-term neuroprotection of cone photoreceptors in a mouse model of retinal disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019; 60: 3221–3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Roche SL, Ruiz-Lopez AM, Moloney JN, Byrne AM, Cotter TG. Microglial-induced Muller cell gliosis is attenuated by progesterone in a mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. Glia. 2018; 66: 295–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Byrne AM, Roche SL, Ruiz-Lopez AM, Jackson ACW, Cotter TG. The synthetic progestin norgestrel acts to increase LIF levels in the rd10 mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Vis. 2016; 22: 264–274. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roche SL, Wyse-Jackson AC, Gomez-Vicente V, et al.. Progesterone attenuates microglial-driven retinal degeneration and stimulates protective fractalkine-CX3CR1 signaling. PLoS One. 2016; 11: e0165197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wyse-Jackson AC, Roche SL, Ruiz-Lopez AM, Moloney JN, Byrne AM, Cotter TG. Progesterone analogue protects stressed photoreceptors via bFGF-mediated calcium influx. Eur J Neurosci. 2016; 44: 3067–3079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Doonan F, O'Driscoll C, Kenna P, Cotter TG. Enhancing survival of photoreceptor cells in vivo using the synthetic progestin Norgestrel. J Neurochem. 2011; 118: 915–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li Y, Fariss RN, Qian JW, Cohen ED, Qian H. Light-induced thickening of photoreceptor outer segment layer detected by ultra-high resolution OCT imaging. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016; 57: OCT105–OCT111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Berkowitz BA, Bissig D, Roberts R. MRI of rod cell compartment-specific function in disease and treatment in-ávivo. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2016; 51: 90–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Berkowitz BA, Bissig D, Roberts R. MRI of rod cell compartment-specific function in disease and treatment in vivo. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2016; 51: 90–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Haacke EM, Brown RW, Thompson MR, Venkatesan R. Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Physical Principles and Sequence Design. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Berkowitz BA, Lewin AS, Biswal MR, Bredell BX, Davis C, Roberts R. MRI of retinal free radical production with laminar resolution in vivo free radical production with laminar resolution in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016; 57: 577–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Berkowitz BA, Bredell BX, Davis C, Samardzija M, Grimm C, Roberts R. Measuring in vivo free radical production by the outer retina measuring retinal oxidative stress. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015; 56: 7931–7938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bissig D, Berkowitz BA.. Same-session functional assessment of rat retina and brain with manganese-enhanced MRI. NeuroImage. 2011; 58: 749–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cheng H, Nair G, Walker TA, et al.. Structural and functional MRI reveals multiple retinal layers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006; 103: 17525–17530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Berkowitz BA, Grady EM, Roberts R. Confirming a prediction of the calcium hypothesis of photoreceptor aging in mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2014; 35: 1883–1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Berkowitz BA, Grady EM, Khetarpal N, Patel A, Roberts R. Oxidative stress and light-evoked responses of the posterior segment in a mouse model of diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015; 56: 606–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Li Y, Zhang Y, Chen S, Vernon G, Wong WT, Qian H. Light-dependent OCT structure changes in photoreceptor degenerative rd 10 mouse retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018; 59: 1084–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lu CD, Lee B, Schottenhamml J, Maier A, Pugh EN, Fujimoto JG. Photoreceptor layer thickness changes during dark adaptation observed with ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017; 58: 4632–4643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Berkowitz BA, Olds HK, Richards C, et al.. Novel imaging biomarkers for mapping the impact of mild mitochondrial uncoupling in the outer retina in vivo. PLoS One. 2020; 15: e0226840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Berkowitz BA, Podolsky RH, Qian H, et al.. Mitochondrial respiration in outer retina contributes to light-evoked increase in hydration in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018; 59: 5957–5964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bissig D, Berkowitz BA.. Light-dependent changes in outer retinal water diffusion in rats in vivo. Mol Vis. 2012; 18: 2561–2562. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Adijanto J, Banzon T, Jalickee S, Wang NS, Miller SS. CO2-induced ion and fluid transport in human retinal pigment epithelium. J Gen Physiol. 2009; 133: 603–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hamann S, Kiilgaard JF, la Cour M, Prause JU, Zeuthen T. Cotransport of H+, lactate, and H2O in porcine retinal pigment epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2003; 76: 493–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhao L, Zabel MK, Wang X, et al.. Microglial phagocytosis of living photoreceptors contributes to inherited retinal degeneration. EMBO Mol Med. 2015; 7: 1179–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Li F, Jiang D, Samuel MA. Microglia in the developing retina. Neural Dev. 2019; 14: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rashid K, Akhtar-Schaefer I, Langmann T. Microglia in retinal degeneration. Front Immunol. 2019; 10: 1975–1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Murakami Y, Ikeda Y, Yoshida N, et al.. MutT homolog-1 attenuates oxidative DNA damage and delays photoreceptor cell death in inherited retinal degeneration. Am J Pathol. 2012; 181: 1378–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Oveson BC, Iwase T, Hackett SF, et al.. Constituents of bile, bilirubin and TUDCA, protect against oxidative stress-induced retinal degeneration. J Neurochem. 2011; 116: 144–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Obolensky A, Berenshtein E, Lederman M, et al.. Zinc-desferrioxamine attenuates retinal degeneration in the rd10 mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011; 51: 1482–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Galbinur T, Obolensky A, Berenshtein E, et al.. Effect of para-aminobenzoic acid on the course of retinal degeneration in the rd10 mouse. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2009; 25: 475–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Usui S, Komeima K, Lee SY, et al.. Increased expression of catalase and superoxide dismutase 2 reduces cone cell death in retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Ther. 2009; 17: 778–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Silverman SM, Ma W, Wang X, Zhao L, Wong WT. C3- and CR3-dependent microglial clearance protects photoreceptors in retinitis pigmentosa. J Exp Med. 2019; 216: 1925–1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Piano I, D'Antongiovanni V, Novelli E, et al.. Myriocin effect on Tvrm4 retina, an autosomal dominant pattern of retinitis pigmentosa. Front Neurosci. 2020; 14: 372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Guadagni V, Biagioni M, Novelli E, Aretini P, Mazzanti CM, Strettoi E. Rescuing cones and daylight vision in retinitis pigmentosa mice. FASEB J. 2019; 33: 10177–10192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kutsyr O, Sánchez-Sáez X, Martínez-Gil N, et al.. Gradual increase in environmental light intensity induces oxidative stress and inflammation and accelerates retinal neurodegeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020; 61: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Li B, Gografe S, Munchow A, Lopez-Toledano M, Pan ZH, Shen W. Sex-related differences in the progressive retinal degeneration of the rd10 mouse. Exp Eye Res. 2019; 187: 107773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ronchi JA, Figueira TR, Ravagnani FG, Oliveira HC, Vercesi AE, Castilho RF. A spontaneous mutation in the nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase gene of C57BL/6J mice results in mitochondrial redox abnormalities. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013; 63: 446–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Xu XJ, Wang SM, Jin Y, Hu YT, Feng K, Ma ZZ. Melatonin delays photoreceptor degeneration in a mouse model of autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. J Pineal Res, 10.1111/jpi.12428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Meimaridou E, Kowalczyk J, Guasti L, et al.. Mutations in NNT encoding nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase cause familial glucocorticoid deficiency. Nat Genet. 2012; 44: 740–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Berkowitz BA, Podolsky RH, Lenning J, et al.. Sodium iodate produces a strain-dependent retinal oxidative stress response measured in vivo using QUEST MRI. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017; 58: 3286–3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Cembrowski MS, Spruston N.. Heterogeneity within classical cell types is the rule: lessons from hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2019; 20: 193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gargini C, Terzibasi E, Mazzoni F, Strettoi E. Retinal organization in the retinal degeneration 10 (rd10) mutant mouse: a morphological and ERG study. J Comp Neurol. 2007; 500: 222–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Jacobson SG, McGuigan DB III, Sumaroka A, et al.. Complexity of the class B phenotype in autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa due to rhodopsin mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016; 57: 4847–4858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Grover S, Fishman GA, Brown J. Patterns of visual field progression in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology. 1998; 105: 1069–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]