Abstract

Background and aims:

Culturally relevant and feasible interventions are needed to address limited professional resources in sub-Saharan Africa for behaviorally treating the dual epidemics of HIV and alcohol use disorder. This study tested the efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) intervention to reduce alcohol use among HIV-infected outpatients in Eldoret, Kenya.

Design:

Randomized clinical trial.

Setting:

A large HIV outpatient clinic in Eldoret, Kenya, affiliated with the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare collaboration.

Participants:

A total of 614 HIV-infected outpatients (312 CBT; 302 HL; 48.5% male; mean age: 38.9 years; mean education 7.7 years) who reported a minimum of hazardous or binge drinking.

Intervention and comparator:

A culturally adapted 6-session gender-stratified group CBT intervention compared with Healthy Lifestyles education (HL), each delivered by paraprofessionals over 6 weekly 90-minute sessions with a 9-month follow-up.

Measurements:

Primary outcome measures were percent drinking days (PDD) and mean drinks per drinking day (DDD) computed from retrospective daily number of drinks data obtained by use of the Timeline Followback from baseline through 9-months post-intervention. Exploratory analyses examined unprotected sex and number of partners.

Findings:

Median attendance was 6 sessions across condition. Retention was 85% through the 9-month follow-up. PDD and DDD marginal means were significantly lower in CBT than HL at all three study phases. Maintenance period: PDD–CBT 3.64 (0.70), HL 5.72 (0.71), mean difference 2.08 (95% CI 0.13-4.04); DDD–CBT 0.66 (0.10) HL 0.98 (0.10), mean difference 0.31 (95% CI 0.05-0.58). Risky sex decreased over time in both conditions, with a temporary effect for CBT at the 1-month follow-up.

Conclusions:

A cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention was more efficacious than Healthy Lifestyles education in reducing alcohol use among HIV-infected Kenyan outpatient drinkers.

Keywords: HIV, alcohol, cognitive-behavioral therapy, randomized clinical trial, paraprofessional, Kenya

Introduction

Worldwide, 71% of 35 million HIV-infected individuals live in sub-Saharan Africa (1). These individuals have demonstrated a high rate of DSM-IV alcohol dependence (2-4) often involving the consumption of inexpensive local brew with high ethanol content (5) and a high rate of hazardous drinking (score of 8 or more on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (6). Hazardous drinking is associated with imperfect adherence to antiretrovirals (ARVs) (7), comorbid medical diseases and AIDS-defining conditions (8), and increased risk of unprotected sex (9, 10). In Kenya, alcohol use correlates with HIV infection (11, 12) and risk of sexually transmitted infections (13, 14). In both the U.S. and Africa, heavy drinking limits the success of HIV prevention efforts (15-17). Hence, effective alcohol interventions are needed in sub-Saharan Africa as the first step to HIV risk reduction.

Cultural adaptation of treatment is important because many evidence-based behavioral interventions have been developed and tested among Caucasian middle-class Americans (18). Further, beliefs about behavior change, sociopolitical influences, socioeconomic resources and health knowledge may differ substantially across cultural settings.

We conducted a randomized clinical trial (RCT) evaluating a culturally adapted group Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) intervention delivered by paraprofessionals to reduce alcohol use among HIV-infected outpatients in Eldoret, Kenya. CBT is a structured, skills-based approach largely informed by social-cognitive theory (19, 20), which construes the maintenance of addictive behaviors at least in part as learned behaviors to cope with stress and problems (21). CBT was selected for Kenyan adaptation because of its strong empirical support in both individual and group formats to reduce alcohol use (22-27) and prior successful applications in sub-Saharan Africa (28, 29). We adapted CBT for Kenyan culture to reference local settings, employ rural images in treatment materials, address misinformation about alcohol, and deliver CBT in Kiswahili in six rather than 12 sessions to make it more acceptable to participants.

Our initial randomized pilot study (n=75) of this CBT intervention, delivered by paraprofessional counselors with fidelity in the same population and setting, showed reduced alcohol use in CBT when compared against an assessment-only condition through the final 3-month follow-up (5, 30-32).

The purpose of the current efficacy study was to compare CBT against a time- and attention-controlled Healthy Lifestyles education intervention (HL) in a larger sample size with a longer 9-month follow-up period. Our primary aim was to test the effect of CBT on alcohol use when compared to HL in a sample of 614 HIV-infected outpatient drinkers in western Kenya. We hypothesized that CBT would demonstrate significantly lower report of Percent Drinking Days (PDD) and Drinks per Drinking Day (DDD) through the 9-month follow-up period. Secondary analyses included the evaluation of counselor adherence to the protocol and competence, and therapeutic alliance. Finally, exploratory analyses examined homework adherence, unprotected sexual behavior (UPS) and number of sexual partners by condition.

Methods

Design

This study was an RCT comparing CBT (experimental condition) against HL (active control), each delivered in 6 weekly 90-minute sessions with a 9-month follow-up. Alcohol use was evaluated across 3 study phases: treatment (0-6 weeks), follow-up (7-30 weeks) and maintenance (31-46 weeks). Participant recruitment occurred over 38 months from July 2012 to September 2015, and follow-up interviews were completed in August 2016.

Participants

Kenya is in East Africa with 49 million citizens. In 2015, HIV prevalence was estimated to be 5.9% in Kenya (33). There are few professional resources for treating alcohol use disorders, e.g., in 2009, 70 psychiatrists served the entire country (34). This trial was performed within the clinical services of the US Agency for International Development—Academic Model Providing Access to Health Care program (AMPATH) (35, 36), which provides education, performs research and provides care for more than 85,000 HIV-infected patients in western Kenya. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by IRBs at all affiliated universities.

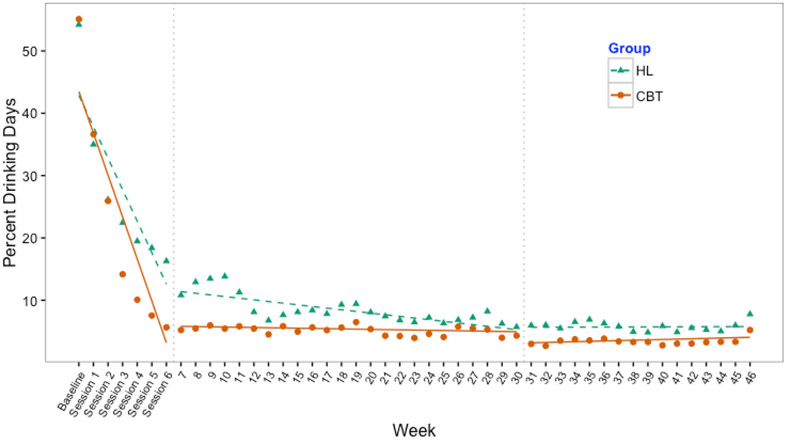

Inclusion criteria were: age ≥ 18 years; enrollment as an AMPATH HIV outpatient attending any of 4 AMPATH HIV clinics; hazardous drinking criteria (score of 3 or more on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C) (37, 38) or binge drinking (6 or more drinks per occasion at least monthly); alcohol use in the past 30 days; verbal working knowledge of Kiswahili; living within one hour travel distance from the Eldoret clinic affiliated with MTRH, where the study was conducted; and being available during the weekly group time (see CONSORT diagram, Figure 1). Exclusion criteria were participation in the CBT pilot study, cohabitation or regular contact with a current study participant (to minimize intervention contamination), impaired physical mobility (due to staircase-only access to study offices), and active psychosis or active suicidality, which were assessed through screening. Positive psychiatric screens were followed with a referral to psychiatrists in mental health services.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of eligibility, enrollment, randomization, intervention, and follow-up rates. CBT=cognitive behavioral therapy; HL=Healthy Lifestyles education

*Unrelated deaths are excluded from calculation of retention rate

Sample size

Participants were 614 HIV-infected outpatient drinkers (312 CBT; 302 HL) in western Kenya. We estimated that we would need to enroll 336 participants (168 per condition) to detect a between-group difference of 10 percentage points (15% vs. 25%) for PDD assuming 15% attrition, with 80% power and at an alpha level of 0.05. Additional resources enabled recruitment of a larger sample to facilitate supplementary analyses.

Outcome Measures

Primary outcome measure.

We used the adapted Timeline Followback (TLFB), a reliable and valid retrospective calendar-based measure employing memory cues to assess alcohol use (39-42) to derive PDD and DDD. Based on our previous work (5), we estimated use of local brew (chang’aa, spirit, and busaa, maize beer) by asking participants how much money they spent on personal consumption, and assessed use of commercial drink by asking volume drunk for the respective time periods. Reported cost and volume were then converted into grams of ethanol and divided by 14 grams, to achieve equivalence to a U.S. standard drink. Seven-day retest reliability using the adapted TLFB was .88 for PDD and .92 for DDD (Pearson correlation). Alcohol use was assessed for the past 30 days at baseline, then consecutively thereafter at each follow-up visit through 9-months post-intervention. Interviews were held weekly during the 6-week intervention phase, and at 1-, 3-, 5-, 7- and 9-months post-intervention. If a participant missed a previous interview, the days since the last interview were assessed at the subsequent interview. At every visit, we also assessed withdrawal symptoms using the validated CIWA-Ar (43) and objective alcohol consumption using the Alco Screen® saliva tests donated by Chematics, Inc. This assay assesses alcohol consumed approximately in the last 1 to 6 hours at indications of .02, .04, .08 or .30% as reflected by swab color (44). A positive saliva test precluded participants from attending any CBT and HL group sessions or survey interviews due to concerns of creating alcohol triggers for other participants or potential reporting invalidity. Participants whose score on the CIWA-Ar was 10 or more were provided with medical assessment and free medications, if needed. The CIWA-Ar and TLFB were adapted to the culture and the national Kiswahili language using World Health Organization (WHO)-modified methods (45). Finally, we collected blood samples and analyzed the phosphatidylethanol (PEth) biomarker (46-50) data in the first 127 consecutive study participants. However, we experienced difficulties with the biomarker that we have described elsewhere (51). Because of the identified problems, PEth results did not add an understanding to these outcome data and so we did not send the remaining blood samples to be analyzed.

Secondary outcome measures.

Demographic and clinical variables.

We used medical records to determine whether participants were taking ARVs and compared these results to participant self-report. Viral load was considered undetectable if plasma HIV RNA concentration was <40 copies per milliliter. Fifty-seven viral load samples were missing for the following reasons: 15 did not agree to the optional consent and 42 were missing from the lab. Finally, we assessed tobacco use, marijuana and khat with self-report questions about frequency and quantity of use. For marijuana and khat items, we included this statement: “I’ll now ask you questions regarding your use of drugs. The response given to us by people regarding their usage of drugs will help others. We know that these pieces of information are personal but remember that they will be kept confidential.” These items also contained the qualifier “(even a small amount)”.

Counselor integrity and inter-rater reliability.

The Yale Adherence and Competence Scale (YACS), a reliable and valid therapist integrity rating system for several psychosocial addiction treatments (52, 53), including CBT, general counseling and psychosocial education approaches, was modified for group delivery in Kenya. This scale, completed by independent raters, included 5 CBT-consistent items (e.g., identify triggers), 4 HL-consistent items (e.g., health education), and 4 shared items (e.g., empathy). Each counselor behavior was rated using a 7-point Likert-type scale on two dimensions: adherence (i.e., frequency and extensiveness; 1=not present, 7=extensively) and competence (i.e., skillfulness; 1=very poor, 7=excellent), for a total of 26 items. To examine inter-rater reliability, a sample of 22 YACS sessions was transcribed and translated into English. Sessions were rated by two independent raters. Their ratings showed a high level of inter-rater reliability (mean intraclass correlation coefficients) for adherence for both CBT (mean=0.99) and HL (mean=0.85). Inter-rater reliability for competence was acceptable for CBT (mean=0.61) and HL (mean=0.68) (54).

Working Alliance Inventory (WAI) – short form.

The WAI is a 12-item participant self-report measure assessing the working alliance in the counseling relationship (55, 56) using a 7-point Likert-type scale (1=never, 7=always). Subscales measure client–counselor agreement on therapy goals and therapy tasks and the bond between client and therapist. The WAI was administered after Sessions 1, 3 and 6 (final session). Seven-day test-retest reliability for the WAI was r=.78.

Risky sex.

UPS and number of sexual partners were also assessed using the TLFB. On each day of the calendar, participants were asked the number of times they had engaged in sex and in UPS, and the number of different partners. Participants were asked to endorse sex if they had engaged in vaginal or anal but not oral sex. The total number of UPS events and number of sexual partners in the past 30 days were summed. Seven-day test-retest reliability for UPS was r=.87 and for number of sexual partners was r=.94.

Homework adherence.

Counselors rated each parrticipant’s completion of the outside practice assignment for the 5 post-session assignments. Ratings were: no completion 0% (0), partial completion (less than 100%) (1) or full completion (100%) (2) .

Procedures

Recruitment

HIV outpatients at the Eldoret clinic were approached by same-sex research staff and asked for verbal consent for a brief interview to describe a health behavior study and determine eligibility. These included those who: 1) had previously reported alcohol use during their first clinic visit, 2) came for unscheduled visits, 3) self-referred in response to posted flyers, or 4) were referred by clinicians in any of the 4 designated outpatient clinics. Referrals from clinics outside Eldoret included a brief phone assessment to determine eligibility to minimize unnecessary travel. Written informed consent in English or Kiswahili was obtained from all eligible and interested participants. Each participant was compensated at each visit the equivalent of US$5 to cover transportation costs.

Randomization

A stratified block randomization procedure with random block sizes of two and four was generated by an analyst to balance gender and antiretroviral (ARV) use (yes/no) across the two intervention conditions Equal allocation was intended between conditions. Individual assignment based on block was printed in sealed envelopes which were handed to the RA by the study coordinator after each enrolment. Within gender- and ARV-based cohorts, participants were randomly assigned to a condition until a target recruitment of 7 individuals per group was achieved. Attendance in groups generally consisted of 5-7 individuals. Assigned condition was not revealed to participants until they arrived for first intervention sessions. Gender stratification was conducted to avoid reinforcing the secondary status of women in Kenya. ARV stratification was conducted to balance any potential behavioral or medical factors associated with greater severity of HIV/AIDS.

Interviews

All participant interviews were recorded and conducted in Kiswahili by same-sex research staff in a private setting using a computer survey interface. Methods of training research staff have been previously described (30). Staff reviewed every audio-recorded survey for accuracy, and project managers made any corrections. Non-blinded research assistants both recruited and interviewed participants; none delivered study interventions.

Retention

A checklist of potential barriers to attendance was reviewed and addressed during recruitment. Also, regular, brief phone calls were made with participants to maintain contact after the intervention. The purpose of calls was to check-in, answer study-related questions, and to remind participants that study-completion certificates would be issued at the 9-month post-intervention interview.

Counselor training, supervision and integrity

Interventions were delivered by eight paraprofessional counselors with no prior CBT or HL experience. A 2-year post-high school counseling diploma was required. Counselors were trained as described in our previous report (31). Every intervention session was videotaped and reviewed with counselors by supervisors: a US clinician and Kenyan counseling manager during the first half of the study, and the Kenyan manager alone for the remainder of the study. Safety oversight was provided throughout the study by the local psychiatrist. The Kenyan counseling manager was trained as a research therapist in the pilot study. Fifty-two percent of all group intervention sessions (n=274) were randomly selected, translated into English and rated by two highly experienced YACS raters from the Yale Psychotherapy Development Center. Ten percent of translated sessions were randomly selected for review of translation quality, where portions were re-translated and compared with the original translation. No discrepancies were found.

Data and Safety Monitoring

The study included a Data and Safety Monitoring Board with representatives from affiliated universities. Adverse events were monitored during the study and reported to the first author by research staff.

Intervention conditions

Both interventions consisted of 6 weekly 90-minute group sessions conducted in Kiswahili and led by one same-sex counselor. Sessions were organized by gender due to concerns about stigma and were closed due to the consecutive building of knowledge across sessions. Both interventions included HIV-alcohol education in the first session. Safety, monitoring and assessment procedures were identical across both conditions.

CBT.

The purpose of the CBT intervention was to teach coping skills for alcohol reduction. As described previously (30, 31), the CBT intervention protocol was structured and based on a manual, with a recommended alcohol quit date following the second session (see Table 1). Because of the adverse effects of alcohol among HIV-infected individuals (7, 30, 31), abstinence was described as the goal, and successive approximations to abstinence were reinforced.

Table 1.

RAFIKI Study cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) protocol.

| CBT SESSION CONTENT |

|---|

|

SESSION 1 I. Welcome – 5 minutes II. Overview of treatment/expectations – 15 minutes III. HIV/alcohol education – 20-30 minutes IV. Group member introductions and intro to CBT – 40-50 minutes |

|

SESSION 2 I. Check-in and practice exercises– 20-30 minutes II. Reasons for drinking and quitting drinking – 30-40 minutes III. Preparation for quitting – 20-30 minutes QUIT DAY |

|

SESSION 3 I. Check in, practice exercises – 20-30 minutes II. CBT model – 20-30 minutes III. Analysis of behavior – 35-45 minutes |

|

SESSION 4 I. Check in, practice exercise – 45 minutes II. Coping with triggers, urges and high-risk situations – 45 minutes |

|

SESSION 5 I. Check in – 20-30 minutes II. Risky decisions leading to drinking – 30-40 minutes III. Problem-solving – 30 minutes |

|

SESSION 6 I. Check in practice exercise – 20-30 minutes II. Alcohol refusal skills – 40 minutes III. Develop a long term plan; and wrap up –20-30 minutes |

HL.

The purpose of the HL intervention was to teach healthy lifestyle behaviors. Our previous work in Kenya with this patient population indicated limited health knowledge. For example, 63% of pilot study participants reported that alcohol was beneficial during pregnancy, and women reported purchasing and eating roasted dirt. The HL manual was successfully employed with problem drinkers in the U.S. (57, 58) and was adapted to this culture and setting. For example, we eliminated exercise promotion, as Kenyans engage in physically arduous tasks. We also dispelled nutritional myths, e.g. that eating roasted clay provides nutrients.

Statistical analysis

To test our primary hypotheses, we examined the trajectory and marginal means of alcohol use (PDD/DDD) by condition from baseline to the 9-month post-intervention follow-up. We first examined intra-cluster correlations of outcome scores from individuals in the same intervention group (i.e., group of 5-7 individuals). Correlations were low (PDD: r=0.015, 95% CI=(0.004, 0.06); DDD: r=0.036, 95% CI=0.019, 0.067) so did not require controlling for the grouping effect in the final analysis (59). We then employed mixed-effects models to examine (1) the overall effect of intervention (CBT compared to HL) during the entire study period, and (2) the effect of intervention across three different time periods, allowing for random intercept and slopes. Study intervals analyzed were: active intervention (baseline to week 6), post-intervention follow-up (weeks 7-30), and maintenance period (weeks 31-46). Three intervals were selected consistent with social learning theory, which posits that successful treatment requires initial acquisition of behavior change, the generalization of that change to settings outside of treatment, and finally the maintenance of change over time in settings outside treatment (19, 20). These intervals can reflect different rates of change due to variability in reinforcement rates and level of extra-session generalization of interventions (58, 59).

The mixed models were adjusted for intervention, time (in weeks), an interaction term between intervention and time, waiting time, as well for RA CIWA-Ar withdrawal symptom score (which differed by condition). We calculated marginal means (i.e., least square means) of PDD and DDD in each condition over the entire study period, and each of the 3 time intervals. We assumed that missing occurred at random (MAR), which would provide valid inference for the mixed modeling sroach. We conducted sensitivity analyses for MAR, assuming that CBT and HL interventions had no effect, so missing outcomes among lost-to-follow-up participants were the same as baseline scores.

As exploratory analyses, we examined whether UPS, which was not targeted in the interventions, differed by condition at 3 timepoints (baseline, 1-month and 9-month post-intervention follow-up) using logistic regression. We also examined via t-test any differences in number of sexual partners by condition at 3 timepoints (baseline, 1-month and 9-month post-intervention follow-up). Finally we examined whether homework adherence, averaged across the 5 assignments, was related to alcohol use (PDD/DDD) and differed by intervention condition (CBT/ HL) using t-test, or modified the effect of the intervention on alcohol use using regression analysis. SAS version 9.4 and R version 3.4.3 software were used for analyses.

Results

Recruitment, retention and adverse events

A total of 1474 participants were screened for eligibility, and 860 were excluded, primarily because they did not drink alcohol in the past 30 days. Participants were randomized: 312 to CBT and 302 to HL (Figure 1). Waiting time for initiation of the intervention was on average 25.06 days (SD=11.6) and did not vary by gender (p= 0.795) or condition (p=0.740). Eighty-eight intervention groups were run, 44 per intervention and 44 per gender. Attendance was high and identical for both intervention conditions: Median (IQR)=6.0 (1.0, 6.0). Retention at 9-months post-intervention was high and similar by condition: CBT 86% and HL 83%. Serious adverse events consisted of eight deaths from non-study-related causes: 2 individuals in CBT and 6 in HL.

Participant baseline characteristics

Average age was 38.9 years (SD=8.0), and highest mean year of education completed was 7.7 (SD=3.6). Median annual income was equivalent to US $240. Participants were diagnosed with HIV 6.9 years ago (SD=4.2), and 84.7% were prescribed ARVS (Table 2). Of those on ARVs with available lab samples (n=472), 30.3% had a detectable viral load, which exceeds the 10% threshold desired by UNAIDS (60). Additionally, only 21% of those on ARVS met the threshold for well-controlled HIV infection: a viral load of less than 1,000 (61). At baseline, mean PDD was 54.7%, and mean DDD was 6.3, with 78.5% of participants reporting drinking chang’aa. Seventy-six percent of participants reported a changaa or busaa den to be in their neighborhood.

Table 2.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of participants by study condition

| Total | CBT | HL | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 614 (100.0%) | 312 (50.8%) | 302 (49.2%) |

| Male, N(%) | 298 (48.5) | 152 (48.7) | 146 (48.3) |

| Age (Years), M(SD) | 38.9 (8.0) | 39.2 (8.2) | 38.5 (7.7) |

| Education, highest year completed, Mean(SD) | 7.7 (3.6) | 7.7 (3.7) | 7.7 (3.6) |

| Total estimated income in past year (Kenyan shillings ÷1000), Median(IQR) | 24.0 (9.2, 60.0) | 24.0 (10.0, 60.0) | 24.0 (8.7 60.0) |

| Married, N(%) | 323 (52.6%) | 161 (51.6%) | 162 (53.6%) |

| ARV-initiated, N(%) | 520 (84.7%) | 265 (84.9%) | 255 (84.4%) |

| Time since HIV diagnosis (years), Mean(SD), N = 601 | 6.9 (4.2) | 7.1 (4.2) | 6.7 (4.3) |

| Detectable viral load, N(%), (N=557) | 220 (39.5%) | 118 (41.4%) | 102 (37.5%) |

| Viral load (Log Base 10) (copies/ml), Mean(SD), (N=220) | 3.8 (1.2) | 3.8 (1.2) | 3.8 (1.2) |

| CIWA-Ar withdrawal symptom score (as assessed by research asst), Median(IQR) | 3.0 (1.0, 6.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 5.2) | 3.0 (1.0, 6.0) |

| CIWA-Ar ≥10* | 52 (8.5%) | 20 (6.4%) | 32 (10.6%) |

| CIWA-Ar withdrawal symptom score (as assessed by clinician) Median(IQR) (N=51) | 12.0 (5.5, 15.5) | 12.0 (6.8, 15.0) | 11.0 (5.0, 16.0) |

| Drank chang'aa (spirit) past 30 days, N(%) | 482 (78.5%) | 240 (76.9%) | 242 (80.1%) |

| Drank busaa past 30 days, N(%) | 318 (51.8%) | 162 (51.9%) | 156 (51.7%) |

| Chang’aa/busaa home brewery within 200 meters from my home, N(%) | 358 (58.3%) | 185 (59.3%) | 173 (57.3%) |

| AUDIT-C, Mean(SD) | 5.7 (2.4) | 5.7 (2.4) | 5.7 (2.4) |

| AUDIT Total, Mean(SD) | 19.4 (7.4) | 19.5 (7.2) | 19.2 (7.6) |

| Percent drinking days - past 30 days, Mean(SD) | 54.7 (28.9) | 55.1 (28.7) | 54.2 (29.1) |

| Drinks per drinking day – past 30 days (14 grams etoh), Mean(SD) | 6.3 (3.8) | 6.3 (3.6) | 6.3(4.0) |

| Tobacco use in past 30 days, N(%) | 177 (28.8%) | 87 (27.9%) | 90 (29.8%) |

| Number of days smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days, Median(IQR) (N = 177) | 30.0 (18.0, 30.0) | 30.0 (21.5, 30.0) | 30.0 (14.2, 30.0) |

| Number of cigarettes on days, smoked, Median(IQR) (N=177) | 4.0 (3.0, 9.0) | 4.0 (2.5, 10.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 8.8) |

| Marijuana use in past 30 days, N(%) | 42 (6.8%) | 20 (6.4%) | 22 (7.3%) |

| Kuber use in the past 30 days, N(%) | 48 (7.8%) | 22 (7.1%) | 26 (8.6%) |

| Khat (stimulant leaf) use in past 30 days N(%) | 50 (8.1%) | 22 (7.1%) | 28 (9.3%) |

Primary Outcome Measure

Regression models.

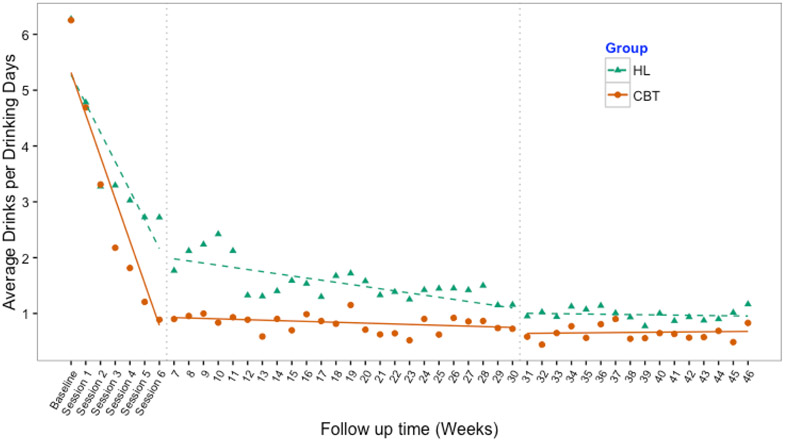

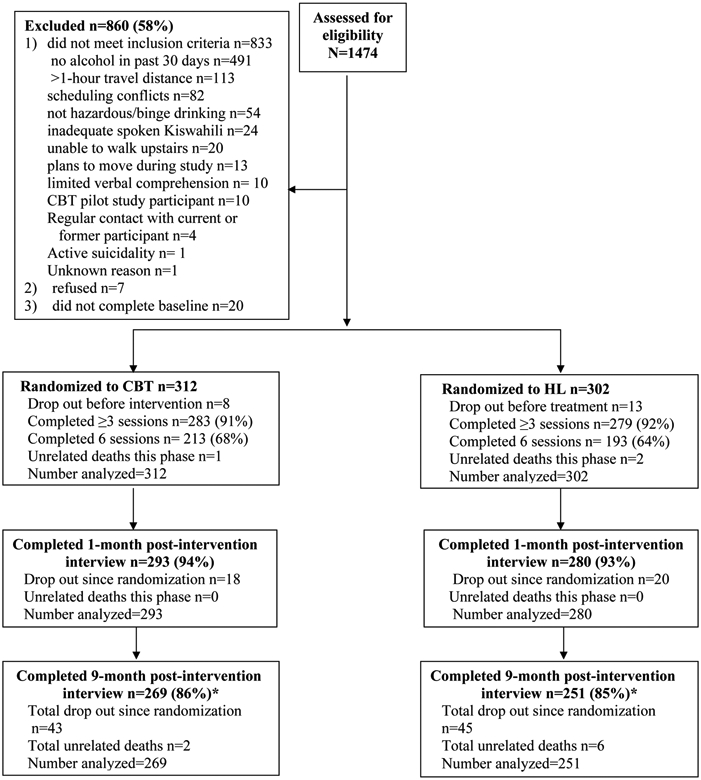

Results of the mixed effects models showed significantly lower PDD and DDD in CBT than HL overall and at all study phases (Table 3). PDD and DDD scores indicated an initial effect (i.e., alcohol reduction) beginning after baseline and through the intervention phase (week 6) across both conditions. Visual inspection of Figures 2 and 3 showed that CBT participants reported reducing alcohol use at a faster rate than controls in this period. During the follow-up (weeks 7-30) and maintenance (weeks 31-46) phases, CBT scores demonstrated a floor effect and maintained reductions. HL participants reported gradual reductions through the follow-up phase and then flattened out during the maintenance phase.

Table 3.

Marginal effect (Absolute least square (LS) mean difference) of CBT compared to HL on percent drinking days and drinks per drinking day averaged over the entire study and across three study phases. Sensitivity analyses for these results

| Absolute least squares mean differences | Sensitivity analyses* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Drinking Days | ||||||||

| Estimate (std. error) | Estimate (std. error) | |||||||

| Study Period |

CBT | HL | LS mean diff (95%CI) |

p-value | CBT | HL | LS mean diff (95%CI) |

p-value |

| Overall | 7.58 (0.678) | 10.26 (0.695) | 2.68 (0.77, 4.58) | 0.0059 | 10.20 (0.876) | 13.63 (0.896) | −3.42(−5.88, −0.97) | 0.0063 |

| Intervention (baseline-6wks) | 21.14 (0.978) | 25.33 (1.001) | 5.20 (2.45, 7.94) | <0.001 | 22.40 (1.025) | 27.62 (1.049) | −5.22(−8.10, −2.34) | 0.0004 |

| Follow up (7-30 wks) | 5.35 (0.748) | 8.11 (0.767) | 2.76 (0.65, 4.86) | 0.0102 | 7.46 (0.897) | 10.81 (0.917) | −3.35(−5.87, −0.83) | 0.0091 |

| Maintenance (31-46 wks) | 3.64 (0.696) | 5.72 (0.712) | 2.08 (0.13, 4.04) | 0.037 | 9.17 (1.167) | 11.55 (1.193) | −2.38(−5.62, 0.86) | 0.1496 |

| Drinks per Drinking Day | ||||||||

| Estimate (std. error) | Estimate (std. error) | |||||||

| Study Period |

CBT | HL | LS mean difld> (95%CI) |

p-value | CBTld> | HLd> | LS mean diff (95%CI) |

p-value |

| Overall | 1.15 (0.091) | 1.69 (0.093) | 0.55 (0.29, 0.80) | <.0001 | 1.47 (0.116) | 2.00 (0.119) | −0.53(−0.85, −0.20) | 0.0015 |

| Intervention (baseline-6wks) | 2.69 (0.128) | 3.47 (0.131) | 0.78 (0.42, 1.14) | <.0001 | 2.98 (0.136) | 3.75 (0.139) | −0.77(−1.15, −0.39) | <0.0001 |

| Follow up (7-30 wks) | 0.83 (0.103) | 1.51 (0.106) | 0.67 (0.38, 0.96) | <.0001 | 1.16 (0.126) | 1.79 (0.129) | −0.64(−0.99, −0.28) | 0.0004 |

| Maintenance (31-46 wks) | 0.66(0.096) | 0.98 (0.098) | 0.31 (0.05, 0.58) | 0.0218 | 1.29 (0.141) | 1.55 (0.144) | −0.25(−0.65, 0.14) | 0.2082 |

Sensitivity analyses assumed that those who were lost-to-follow-up had returned to baseline drinking levels

Figure 2.

Observed means of percent drinking days and mixed effect model fit across three study phases: active intervention (baseline to week 6), follow-up (weeks 7 to 30), and maintenance periods (weeks 31 to 46).

CBT=Cognitive-Behavioral therapy HL=Healthy Lifestyles education.

Note: baseline represents previous 30 days

Figure 3.

Observed means of drinks per drinking day and mixed effect model fit across three study phases: active intervention (baseline to week 6), follow-up (weeks 7 to 30), and maintenance periods (weeks 31 to 46)

CBT=Cognitive-Behavioral therapy HL=Healthy Lifestyles education.

Note: baseline represents previous 30 days

Sensitivity analyses.

The effect of CBT remained significant in all study periods, with the assumption that those who were lost-to-follow-up had returned to baseline drinking levels, except for the maintenance period (weeks 31-46). These results might be expected given that most attrition occurs in later study periods, and missing outcomes were replaced with similar baseline values between CBT and HL.

Medication for withdrawal symptoms.

Provision of benzodiazepine medication for alcohol withdrawal symptoms was not different by intervention condition. Medication was provided 28 times in CBT and 27 times in HL, mostly early in the study, with 6 events occurring during follow-up.

Saliva tests.

There were 80 positive saliva tests (value of .02, .04, .08 or .30% alcohol), 42 in CBT and 38 in HL The majority of positive tests occurred during the intervention phase (CBT=25, HL=23). Fewer positive tests occurred during 9 months of post-intervention follow-up (CBT=15, HL=14).

Secondary outcome measures

CBT and HL integrity and discriminability

Adherence and competence scores of CBT, HL and shared items did not differ significantly by gender (p>.05). The most frequently delivered intervention in CBT sessions was discussion of high-risk situations/triggers (M=6.8, SD=0.8) and in HL sessions was health education (M=5.6, SD=2.4). Regarding common interventions, reflective statements were most frequent in both conditions (M=6.9, SD=0.4 in each condition). These results suggest that the observed content of the sessions was consistent with respective manual guidelines (Table 4).

Table 4.

Means of adherence, competence and therapeutic alliance ratings by intervention condition

| Mean (SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| CBT | HL | P-value | |

| CBT Adherence | N = 136 | N = 138 | |

| 6.0 (1.0) | 1.0 (0.1) | <0.001 | |

| Individual item | |||

| Alcohol assessment | 5.8 (1.9) | 1.0 (0.3) | |

| Coping skills | 6.4 (1.5) | 1.1 (0.3) | |

| Monitor/challenge thoughts | 5.9 (1.8) | 1.0 (0.1) | |

| Monitor feelings | 5.3 (2.0) | 1.0 (0.1) | |

| Identify/cope with high-risk situations | 6.8 (0.8) | 1.0 (0.2) | |

| CBT Competence | N = 135 | N = 12 | |

| 6.1 (0.6) | 4.0 (0.6) | <0.001 | |

| Individual item | |||

| Alcohol assessment | 5.8 (1.1) | 4.5 (0.7) | |

| Coping skills | 6.5 (1.0) | 3.8 (0.4) | |

| Monitor/challenge thoughts | 5.8 (1.1) | 4.0 (NA) | |

| Monitor feelings | 5.5 (1.1) | 4.5 (0.7) | |

| Identify/cope with high-risk situations | 6.7 (0.6) | 3.5 (0.7) | |

| Common items Adherence | N = 136 | N = 138 | |

| 4.6 (0.8) | 3.9 (0.7) | <0.001 | |

| Individual item | |||

| Review homework | 4.3 (1.4) | 3.6 (1.5) | |

| Psychoeducation | 3.3 (2.4) | 3.1 (2.5) | |

| Reflective statements | 6.9 (0.4) | 6.9 (0.4) | |

| Express empathy | 4.1 (2.1) | 2.1 (1.6) | |

| Common items Competence | N=136 | N=138 | |

| 5.6 (0.5) | 5.4 (0.6) | 0.001 | |

| Individual item | |||

| Review homework | 5.5 (1) | 5(0.9) | |

| Psychoeducation | 5.4 (1.2) | 5.7 (1.1) | |

| Reflective statements | 6.3 (0.6) | 5.9 (0.8) | |

| Express empathy | 5.0 (0.8) | 4.8 (0.9) | |

| HL Adherence | N=136 | N=138 | |

| 1.2 (0.4) | 3.5 (1.0) | <0.001 | |

| Individual item | |||

| Promote sweeping behavior change | 1.6 (1.3) | 2.1 (1.6) | |

| Discuss healthier lifestyle | 1.1 (0.4) | 3.7 (2.3) | |

| Health education: sleep, nutrition, values, time management | 1.0 (0) | 5.6 (2.4) | |

| Assess progress toward lifestyle goals | 1.0 (0.3) | 2.5 (2.5) | |

| HL Competence | N=37 | N=137 | |

| 4.9 (0.9) | 5.9 (0.5) | <0.001 | |

| Individual item | |||

| Promote sweeping behavior change | 4.9 (0.9) | 5.5 (0.8) | |

| Discuss healthier lifestyle | 4.2 (0.9) | 5.9 (0.9) | |

| Health education: sleep, nutrition, values, time management | n/a | 5.9 (0.9) | |

| Assess progress toward lifestyle goals | 6.0 (0) | 6.4 (0.8) | |

| Therapeutic alliance | N=266 | N=263 | |

| Week 1 | 5.6 (0.8) | 5.6 (0.8) | 0.91 |

| Week 3 | 5.7 (0.8) | 5.7 (0.8) | 0.96 |

| Week 6 | 5.8 (0.7) | 5.8 (0.8) | 0.69 |

The Yale Adherence and Competence Scale was used to assess adherence and competence. The Working Alliance Inventory-short form was used to assess therapeutic alliance

WAI

Therapeutic alliance was high and there were no significant differences by condition at any timepoint (Table 4).

Risky sex

Descriptive data showed that the percentage of individuals engaging in UPS and the number of sexual partners diminished over time in both conditions (Table 5). Odds of engaging in UPS, which were not different by condition at baseline, were significantly lower in CBT at the 1-month follow-up (CBT: OR [95% CI]: 0.63 [0.42, 0.95]) but not at the 9-month follow-up (CBT: OR [95%CI]: 1.23 [0.82, 2.01]). The t-test of number of sexual partners also indicated a short-term effect of CBT at the 1-month follow-up, with differences not significant at the 9-month follow-up.

Table 5.

Percentage of sexually active individuals who engaged in unprotected sex (UPS) and mean and standard deviation of number of sexual partners by intervention condition at 3 study timepoints

| CBT | HL | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study timepoint | N | UPS N(%) |

# of partners M(SD) |

UPS N(%) |

# of partners M(SD) |

p- value* |

| Baseline | 508 | 159 (62.6%) | 2.0 (2.7) | 158 (62.2%) | 2.3 (3.5) | 0.216 |

| 1-month follow-up | 380 | 71 (38.4%) | 0.9 (0.8) | 97 (49.7%) | 1.1 (1.4) | 0.003 |

| 9-month follow-up | 321 | 63 (38.4%) | 0.8 (0.9) | 51 (32.5%) | 0.8 (0.9); | 0.532 |

P-value corresponds to T-test result comparing the average number of sexual partners between CBT and HL

Homework adherence

Results showed that average homework completion was 1.8 (SD=0.5) in CBT and 1.6 (SD=0.5) in HL (p<0.001). Results of the t-tests across conditions showed homework adherence was significantly negatively associated with PDD at 1-month and 9-month follow-ups (p<.001) and with DDD at the 9-month follow-up (p=.006). Homework adherence was not significantly associated with DDD at the 1-month follow-up (p=.112). Results of regression analyses showed that homework adherence improves the effect of CBT on PDD (p<.001) and DDD (p=.04) at the 1-month follow-up. The effect modification was not significant for PDD or DDD at the 9-month follow-up (p>.05).

Discussion

This randomized efficacy trial showed that a culturally adapted group CBT delivered by paraprofessionals to HIV-infected outpatients in western Kenya is effective in reducing alcohol use when compared to an active health education intervention. CBT was more efficacious than HL in reducing reported alcohol use through the 9-month post-intervention follow-up for both primary outcomes (PDD and DDD). During the intervention phase, CBT participants reported more rapid reductions in alcohol use than HL participants. During the follow-up phase, CBT participants maintained reductions while HL participants continued to report gradual reductions in use. Sensitivity analyses showed these effects were robust during the intervention and follow-up phases, though they weakened in the maintenance phase under the assumption that those lost-to-follow-up had returned to baseline drinking levels.

Independent integrity ratings of CBT and HL sessions showed discriminability of content between interventions and that paraprofessional counselors delivered both interventions with acceptable adherence and competence. Therapeutic alliance and attendance were high and not significantly different by condition. These findings indicate that HL was a credible control condition and that group CBT can be delivered well by paraprofessional counselors in sub-Saharan Africa.

Group CBT to reduce alcohol use presents a viable first step to counteract the dual public health crises of alcohol use disorder and HIV transmission in sub-Saharan Africa. Interventions for alcohol use disorder in HIV-infected individuals have primarily targeted HIV risk reduction and improved antiretroviral treatment adherence. However, a growing literature suggests that heavy drinking limits the success of HIV prevention efforts (15-17). In addition, a group paraprofessional delivery model provides a useful tool in settings with few professional resources by expanding available interventions for counteracting public health crises. Indeed, the cost-effectiveness of our paraprofessional delivery method has been confirmed in several simulation modeling papers based on our pilot study data (62-64). Researchers in one study estimated that alcohol use was responsible for an estimated 13% of new HIV infections in Kenya and proposed that our intervention delivery model could prevent nearly half of these new HIV infections caused by alcohol use (63).

Of note, the report of rapid decreases in alcohol use in the CBT condition was not consistent with the “sleeper effect” sometimes observed in CBT. We observed a similar pattern during our pilot study (30). In our pilot study groups and debriefings, some women and men reported that learning about harmful health effects of alcohol was motivating to reduce drinking. Women in particular were unaware of such consequences among HIV-infected persons. Several men reported that assessment of brew by the financial cost was informative and motivating as well. It is possible that psychoeducation may have developed a discrepancy between participant drinking behavior and negative consequences. Hence, brief motivational approaches such as Motivational Interviewing (65) could be explored for this patient population, perhaps in conjunction with skills training.

As noted earlier, the design of this trial has many strengths that lend confidence to the integrity of these data. These include standardized protocols for intervention delivery, training and integrity ratings; data quality checks of all surveys using audiotapes and the use of a strong attention- and time-matched active control condition. However, the study also has several limitations that should be considered in interpreting its results. Limitation of the study include the reliance on self-report of alcohol use and assessment interviews by non-blinded research assistants. Another limitation is potential assessment reactivity although both conditions were matched for number of assessments, and intervention time and attention. Finally, the cutoff between the follow-up and maintenance phase intended to indicate differences in reinforcement following over time is somewhat arbitrary.

In conclusion, our findings show that CBT is a viable tool in combatting alcohol use disorder in sub-Saharan Africa. The next major research step is testing the CBT intervention in an effectiveness/implementation trial. Future research may also examine enhanced CBT interventions that co-target both heavy drinking and sexual risk behaviors.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Grant R01AA020805 from the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). It was also supported in part by a grant to the USAID-AMPATH Partnership from the United States Agency for International Development as part of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. Manuscript preparation manuscript was supported in part by NIAAA Grant 2K05 16928. We thank Joanne Corvino and Karen Hunkele for providing independent intervention integrity ratings. We extend appreciation to Chematics, Inc. of North Webster, Indiana for generous donations of alcohol saliva tests for this research program. We thank the AMPATH clinic staff for facilitating this research and the participants for contributions to intervention testing.

Footnotes

The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01503255 on January 4, 2012

We have no conflicts of interest to report

References

- 1.(UNAIDS) UNAIDS. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. The Gap Report 2014. [Available from: http://files.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2014/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf.

- 2.Othieno CJ, Kathuku DM, Ndetei DM. Substance abuse in outpatients attending rural and urban health centres in Kenya. East Afr Med J. 2000;77(11):592–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Amundsen A, Grant M. Alcohol consumption and related problems among primary health care patients: WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption-I. Addiction. 1993;88:349–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for primary care. Geneva, WHO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papas RK, Sidle JE, Wamalwa ES, Okumu TO, Bryant KL, Goulet JL, et al. Estimating alcohol content of traditional brew in Western Kenya using culturally relevant methods: the case for cost over volume. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(4):836–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaffer DN, Njeri R, Justice AC, Odero WW, Tierney WM. Alcohol abuse among patients with and without HIV infection attending public clinics in western Kenya. East Afr Med J. 2004;81(11):594–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braithwaite RS, McGinnis KA, Conigliaro J, Maisto SA, Crystal S, Day N, et al. A temporal and dose-response association between alcohol consumption and medication adherence among veterans in care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(7):1190–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Justice AC, Lasky E, McGinnis KA, Griffith T, Skanderson M, Conigliaro J, et al. Comorbid disease and alcohol use among veterans with HIV infection: a comparison of measurement strategies. Med Care. 2006;44(8 Suppl 2):S52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Apostolopoulos Y, Sonmez S, Yu CH. HIV-risk behaviors of American spring break vacationers: A case of situational disinhibition? Int J STD & AIDS. 2002;13:733–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seage GR 3rd, Holte S, Gross M, Koblin B, Marmor M, Mayer KH, et al. Case-crossover study of partner and situational factors for unprotected sex. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31:432–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayisi JG, van Eijk AM, ter Kuil OF, Kolczak MS, Otieno JA, Misore AO, et al. Risk factors for HIV infection among asymptomatic pregnant women attending an antenatal clinic in western Kenya. Int J STD & AIDS. 2000;11:393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hargreves JR. Socioeconomic status and risk of HIV infection in an urban population in Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7:793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feldblum PJ, Kuyoh M, Omari M, Ryan KA, Bwayo JJ, Welsh M. Baseline STD prevalence in a community intervention trial of the female condom in Kenya. Sex Transm Infect. 2000;76:454–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lavreys L Human herpesvirus 8: seroprevalence and correlates in prostitutes in Mombasa, Kenya. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:359–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bedoya CA, Mimiaga MJ, Beauchamp G, Donnell D, Mayer KH, Safren SA. Predictors of HIV transmission risk behavior and seroconversion among Latino men who have sex with men in Project EXPLORE. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(3):608–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fritz K, McFarland W, Wyrod R, Chasakara C, Makumbe K, Chirowodza A, et al. Evaluation of a peer network-based sexual risk reduction intervention for men in beer halls in Zimbabwe: results from a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(8):1732–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, Cain D, Smith G, Mthebu J, et al. Randomized trial of a community-based alcohol-related HIV risk-reduction intervention for men and women in Cape Town South Africa. Annals Behav Med. 2008;36:270–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernal G, Bonilla J, Bellido C. Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: Issues for cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. J Abnormal Child Psychol. 1995;23(1):67–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bandura A Principles of Behavior Modification. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bandura A Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monti PM, Kadden RM, Rohsenow DJ, Cooney NL, Abrams DB. Treating Alcohol Dependence: A Coping Skills Training Guide. New York: The Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadden RM, Cooney NL, Getter H, Litt MD. Matching alcoholics to coping skills or interactional therapy: Posttreatment results. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:698–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller WR, Zweben J, Johnson WR. Evidence-based treatment: Why, what, where, when and how? J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;29:267–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Project Match Research G. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58(1):7–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Treating alcohol and drug abuse: An evidence-based review. Berglund M, Thelander S, Jonsson E, editors. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finney JW, Moos RH. Psychosocial treatments for alcohol use disorders In: Nathan PE, Gorman JM, editors. A Guide to Treatments that Work. 2nd London: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller WR, Wilbourne PL. Mesa Grande: A methodological analysis of clinical trials of treatments for alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2002;3:265–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osinowo HO, Olley BO, Adejumo AO. Evaluation of the effect of cognitive therapy on perioperative anxiety and depression among Nigerian surgical patients. West African Journal of Medicine. 2003;22(4):338–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones DL, Ross D, Weiss SM, Bhat G, Chitalu N. Influence of partner participation on sexual risk behavior reduction among HIV-positive Zambian women. J Urb Health. 2005;82(3 Suppl 4):92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papas RK, Sidle JE, Gakinya BN, Baliddawa JB, Martino S, Mwaniki MM, et al. Treatment outcomes of a stage 1 cognitive-behavioral trial to reduce alcohol use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected out-patients in western Kenya. Addiction. 2011;106(12):2156–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papas RK, Sidle JE, Martino S, Baliddawa JB, Songole R, Omolo OE, et al. Systematic cultural adaptation of cognitive-behavioral therapy to reduce alcohol use among HIV-infected outpatients in western Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(3):669–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papas RK, Gakinya BN, Baliddawa JB, Martino S, Bryant KJ, Meslin EM, et al. Ethical issues in a stage 1 cognitive-behavioral therapy feasibility study and trial to reduce alcohol use among HIV-infected outpatients in western Kenya. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2012;7(3):29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.(UNAIDS). The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. HIV and AIDS estimates. Kenya: (2015) 2015. [Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/kenya. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiima D, Jenkins R. Mental health policy in Kenya -an integrated approach to scaling up equitable care for poor populations. Int J Ment Health Sys. 2010;4:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Einterz RM, Kimaiyo S, Mengech HNK, Khwa-Otsyula BO, Esamai F, Quigley F, et al. Responding to the HIV pandemic: the power of an academic medical partnership. Acad Med. 2007;82(812):818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mamlin J, Kimaiyo S, Nyandiko W, Tierney W, Einterz R. Academic institutions linking access to treatment and prevention: Case study. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gordon AJ, Maisto SA, McNeil M, Kraemer KL, Conigliaro RL, Kelley ME, et al. Three questions can detect hazardous drinkers. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(4):313–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, DeLaFuente JR, Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sobell LC, Maisto SA, Sobell MB, Cooper AM. Reliability of alcohol abusers’ self-reports of drinking behavior. Behav Res Ther. 1979;17(2):157–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI, Cancilla A. Reliability of a timeline method: assessing normal drinkers’ reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. Br J Addict. 1988;83(4):393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maisto SA, Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Comparison of alcoholics’ self-reports of drinking behavior with reports of collateral informants. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979;47(1):106–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline Followback: A Technique for Assessing Self-Reported Alcohol Consumption In: Litten RZ, Allen J, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption. 1st Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press; 1992. p. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, Naranjo CJ, Sellers EM. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: The revised Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84:1353–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chematics Inc. Alco-Screen Technical Information. North Webster, Indiana: Chematics, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 45.World Health Organization. WHO - Process of translation and adaptation of instruments 2009. [updated 2010/11/01/. Available from: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/.

- 46.Wurst FM, Alexson S, Wolfersdorf M, Bechtel G, Forster S, Alling C, et al. Concentration of fatty acid ethyl esters in hair of alcoholics: comparison to other biological state markers and self reported-ethanol intake. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39(1):33–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hahn JA, Cook RL, Saitz R, Cheng DM, Muyindike WR, Hu X, et al. PEth (Phosphatidylethanol) versus Self-Report: A Comparison for Assessing Alcohol Use in Research Studies of Heterogeneous HIV-Infected Populations. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(Supp 1):136A.25516156 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Helander A, Peter O, Zeng Y. Monitoring of the alcohol biomarkers PEth, CDT and EtG/EtS in an outpatient treatment setting. Alcohol and Alcoholism (Oxford). 2012;47(5):552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Varga A, Hansson P, Lundqvist C, Alling C. Phosphatidylethanol in blood as a marker of ethanol consumption in healthy volunteers: comparison with other markers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22(8):1832–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Viel G, Boscolo-Berto R, Cecchetto G, Fais P, Nalesso A, Ferrara SD. Phosphatidylethanol in blood as a marker of chronic alcohol use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(11):14788–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Papas RK, Gakinya BN, Mwaniki MM, Keter AK, Lee H, Loxley MP, et al. Associations Between the Phosphatidylethanol Alcohol Biomarker and Self-Reported Alcohol Use in a Sample of HIV-Infected Outpatient Drinkers in Western Kenya. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(8):1779–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carroll KM, Nich C, Rounsaville BJ. Use of observer and therapist ratings to monitor delivery of coping skills treatment for cocaine abusers: Utility of therapy session checklists. Psychother Res. 1998;8:307–20. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carroll KM, Nich C, Sifry RL, Nuro KF, Frankforter TL, Ball SA, et al. A general system for evaluating therapist adherence and competence in psychotherapy research in the addictions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;57:225–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bonett DG. Sample size requirements for estimating intraclass correlations with desired precision. Stat Med. 2002;21(9):1331–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Busseri MA, Tyler JD. Interchangeability of the Working Alliance Inventory and Working Alliance Inventory, Short Form. Psychol Assess. 2003;15(2):193–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Horvath AO, Greenberg LS. Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. J Couns Psychol. 1989;36(2):223. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Connors GJ, Walitzer KS. Reducing alcohol consumption among heavily drinking women: evaluating the contributions of life-skills training and booster sessions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(3):447–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walitzer KS, Connors GJ. Thirty-month follow-up of drinking moderation training for women: a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(3):501–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess. 1994;6(4):284. [Google Scholar]

- 60.UNAIDS. 90–90–90 - An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic 2017. [Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2017/90-90-90.

- 61.Word Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection - 2nd Edition 2016. [Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/arv/arv-2016/en/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kessler J, Ruggles K, Patel A, Nucifora K, Li L, Roberts MS, et al. Targeting an alcohol intervention cost-effectively to persons living with HIV/AIDS in East Africa. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(11):2179–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Braithwaite RS, Nucifora KA, Kessler J, Toohey C, Mentor SM, Uhler LM, et al. Impact of interventions targeting unhealthy alcohol use in Kenya on HIV transmission and AIDS-related deaths. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(4):1059–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Braithwaite RS, Nucifora KA, Kessler J, Toohey C, Li L, Mentor SM, et al. How inexpensive does an alcohol intervention in Kenya need to be in order to deliver favorable value by reducing HIV-related morbidity and mortality? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(2):e54–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arkowitz H, Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in the treatment of psychological problems: Guilford Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]