Abstract

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive disease requiring maintenance therapy. According to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) strategy report, bronchodilation with long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) and long-acting β2-agonists (LABAs), administered via inhalers, is currently the mainstay of COPD treatment. Combined LAMA/LABA therapies have been shown to improve patient health status, lung function and breathlessness. Here, we wanted to report patient satisfaction with the Respimat® Soft Mist™ inhaler (SMI).

Methods

This was a pooled analysis of SPIRIT® (NCT02675517) and OTIVACTO® (NCT02719639), two open-label, single-arm, non-interventional studies of physical function in patients with COPD. Patients were treated with tiotropium/olodaterol 5/5 μg for approximately 6 weeks via the SMI. SPIRIT was conducted in Germany; OTIVACTO was conducted in nine European countries. The primary endpoints have been reported previously. Here, we assess patient satisfaction with inhalation and handling, and patient adherence to treatment with the tiotropium/olodaterol SMI in patients with COPD. These were assessed through self-reported questionnaires and physician general assessments.

Results

Baseline data were collected from 9180 patients from the SPIRIT and OTIVACTO studies. The majority of patients were GOLD group A (25.59%) or B (46.12%). After 6 weeks of treatment with tiotropium/olodaterol, 85.78% of patients were ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with inhaling from the device, and 84.33% of patients were ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with the handling of the inhaler. Treating physicians reported patient adherence as ‘high’ during the study, with 98.57% of patients regularly using the tiotropium/olodaterol SMI. Furthermore, 95.45% of patients expressed a willingness to continue using the tiotropium/olodaterol SMI at the end of the observation period.

Conclusion

In this study, over 9000 patients reported satisfaction with respect to inhalation and handling of the Respimat SMI, and patient adherence was high.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02675517 (SPIRIT) and NCT02719639 (OTIVACTO).

Keywords: Bronchodilator, COPD, Inhaler, Non-interventional studies, Observational patient satisfaction, OTIVACTO, Soft Mist, SPIRIT

Plain Language Summary

Inhalation devices are the main method of delivering treatments to patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). However, there are many devices available, which can lead to confusion and poor inhaler technique. To help doctors decide which device to give to their patients, they consider whether the patient would be happy with the device and whether they can use it correctly. This study pooled data from two large real-life studies to assess patient satisfaction with the Respimat® Soft Mist™ inhaler. Patients assessed their satisfaction and willingness to continue using the device at the end of the study period.

The pooled data included over 9000 patients on a range of baseline therapies. After 6 weeks of using the trial device, over 85% of patients were satisfied or very satisfied with inhaling from the device, and over 84% were satisfied with the handling of the device. Physicians reported that nearly 99% of patients regularly used their device. Also, over 95% of the patient population reported that they continued using the inhaler at the end of the study.

Overall, these results support the view that many patients with COPD across a wide range of severities and baseline characteristics demonstrated satisfaction with the Respimat® Soft Mist™ inhaler to control their disease.

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Due to the number of different inhalers available to patients with COPD, this can lead to confusion and incorrect device use, which can affect patient adherence to therapy. |

| What was learned from this study? |

| This pooled analysis, which focused specifically on patients from the SPIRIT and OTIVACTO studies, showed high satisfaction with the Respimat® Soft Mist™ inhaler (SMI). |

| In the pooled population, and in the individual studies, a high proportion of patients were satisfied with inhalation and handling of the device. |

| Patient adherence and post-study use was high in the pooled cohort, with 95.45% continuing to use the SMI after the study concluded. |

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive disease requiring maintenance treatment for symptom relief [1, 2]. Bronchodilation with long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) and long-acting β2-agonists (LABAs), administered via inhalers, is currently the mainstay of COPD treatment [2–4]. Due to the number of different inhalers available to patients with COPD, this can lead to confusion and incorrect device use [2, 5, 6]. Unfortunately, in COPD, inhaler technique and patient adherence remain suboptimal, with 40–60% of patients failing to comply with their prescribed therapy [5, 7].

To obtain pharmacotherapy success, patient adherence is important; this can depend on a patient’s experience with their inhaler [5, 6, 8], as well as their coordination and inhalation capacity [4, 9]. The Respimat® Soft Mist™ inhaler (SMI) is a suitable device for a wide range of patients [10–12], even for patients with low inspiratory flow [4], as dose delivery is independent of inspiratory capacity [11, 13].

Tiotropium, a once-daily LAMA, and olodaterol, a once-daily LABA, have been shown to provide long-term improvements in lung function, quality of life and exercise capacity [14, 15]; these can be combined as a dual therapy (tiotropium/olodaterol), delivered via an SMI [16, 17]. Dual bronchodilator therapy is recommended in the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) strategy report as initial therapy for highly symptomatic patients with a history of exacerbations (≥ 2 moderate exacerbations or ≥ 1 leading to hospitalisation), or in patients who experience dyspnoea or exacerbations (and have a low eosinophil count) whilst on monotherapy [2]. In the American Thoracic Society (ATS) clinical practice guidelines, dual therapy is recommended over monotherapy for patients with dyspnoea or exercise intolerance [18]; and the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence recommends LAMA/LABA for patients without indication of asthmatic features, or features suggesting steroid responsiveness, who remain breathless or have exacerbations despite optimised non-pharmacological management and use of short-acting bronchodilators [19].

This analysis pooled data from two sister non-interventional studies: SPIRIT® (NCT02675517) and OTIVACTO® (NCT02719639) [20, 21]. The aim of the analysis was to assess self-reported patient satisfaction regarding inhalation and handling, as well as treatment adherence, using the tiotropium/olodaterol SMI in patients with COPD.

Methods

Study Design

The clinical studies SPIRIT and OTIVACTO, and description of their inclusion and exclusion criteria, have been published previously [20, 21]. In each study, patients received tiotropium/olodaterol via an SMI over a 6-week period. SPIRIT involved 258 sites in Germany; OTIVACTO enrolled patients across nine European countries [20, 21]. Patients were trained on how to use the inhaler by their treating physician at study entry. To be consistent with real-life conditions, physicians were not restricted regarding their method of patient instruction. Additionally, there were no prespecified or predefined instruction methods. This post hoc analysis pooled data from these two large, European, non-interventional, prospective studies that had similar study designs.

Study Assessments

Here, we report data on patient satisfaction and adherence from the SPIRIT and OTIVACTO studies. Baseline data were collected at visit 1 (prior to inhaler treatment). Patient satisfaction regarding inhalation and handling of the inhaler device was assessed at the end of the study (visit 2), approximately 6 weeks after visit 1, via a seven-point patient satisfaction questionnaire (ranging from ‘very satisfied’ to ‘very dissatisfied’). Using a yes/no questionnaire, patients self-reported their regular inhaler use and willingness to continue inhaler use after the end of the observation period; these were used by treating physicians to assess patient adherence.

Subgroup Analysis

Patients in the pooled population were stratified by their GOLD group (A–D) according to GOLD 2017 guidelines [22]. Additionally, for the individual SPIRIT and OTIVACTO studies, data were analysed by GOLD stage (1–4) and by comparing maintenance-naïve patients (those not receiving LAMA, LABA or inhaled corticosteroids at baseline) with pretreated patients (those receiving maintenance therapy at baseline). All statistical analyses in this study were descriptive.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Both SPIRIT and OTIVACTO were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, International Conference on Harmonisation Harmonised Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice and local regulations. The protocols were approved by the authorities and the ethics committees of the respective institutions. Signed informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Results

Baseline data were collected from 9180 patients from SPIRIT (n = 1737) and OTIVACTO (n = 7443) (Table 1). Most patients were classified as GOLD group B (46.12%), A (25.59%) or D (21.56%). Fewer patients were classed as GOLD group C (6.72%). At baseline, the most common treatment used by the study groups was LAMAs (26.96%), followed by LABAs (14.44%). A substantial group were receiving no maintenance therapy at baseline (34.52%).

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| OTIVACTO® (n = 7443) | SPIRIT® (n = 1737)a | Pooled (n = 9180) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at registration, years (SD) | 65.07 (9.33) | 66.51 (10.30) | 65.34 (9.54) |

| Time between initial diagnosis and baseline visit, years (SD) | 4.77 (5.76) | 5.23 (5.90) | 4.86 (5.79) |

| Male, n (%) | 5094 (68.44) | 990 (56.99) | 6084 (66.27) |

| Smoker, n (%) | 3080 (41.38) | 695 (40.01) | 3775 (41.12) |

| Ex-smoker | 3325 (44.67) | 691 (39.78) | 4016 (43.75) |

| Non-smoker | 1038 (13.95) | 350 (20.15) | 1388 (15.12) |

| Gold group, n (%) | |||

| A | 1625 (21.83) | 724 (41.68) | 2349 (25.59) |

| B | 3639 (48.89) | 595 (34.25) | 4234 (46.12) |

| C | 376 (5.05) | 241 (13.87) | 617 (6.72) |

| D | 1803 (24.22) | 176 (10.13) | 1979 (21.56) |

| Baseline pulmonary therapy, n (%)b,c | |||

| Short-acting β2-agonist | 1056 (14.19) | 318 (18.31) | 1374 (14.97) |

| Long-acting β2-agonist | 1100 (14.78) | 226 (13.01) | 1326 (14.44) |

| Short-acting anticholinergic | 513 (6.89) | 20 (1.15) | 533 (5.81) |

| Long-acting anticholinergic | 1999 (26.86) | 476 (27.40) | 2475 (26.96) |

| Long-acting anticholinergic + long-acting β2-agonist | 50 (0.67) | 42 (2.42) | 92 (1.00) |

| Short-acting anticholinergic + short-acting β2-agonist | 1071 (14.39) | 79 (4.55) | 1150 (12.53) |

| Long-acting β2-agonist + inhaled corticosteroid | 859 (11.54) | 156 (8.98) | 1015 (11.06) |

| Inhaled corticosteroids | 326 (4.38) | 93 (5.35) | 419 (4.56) |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 45 (0.60) | 23 (1.32) | 68 (0.74) |

| Theophylline | 719 (9.66) | 13 (0.75) | 732 (7.97) |

| Roflumilast | 36 (0.48) | 20 (1.15) | 56 (0.61) |

| Other | 192 (2.58) | 14 (0.81) | 206 (2.24) |

Patients were classified based on exacerbations and symptoms as outlined in GOLD 2017 [19]

GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; SD, standard deviation

aOne patient’s smoking status was missing from this group

bSome patients were included in multiple groups

cSome patient data were missing

Patient Satisfaction at Week 6

Inhalation Satisfaction

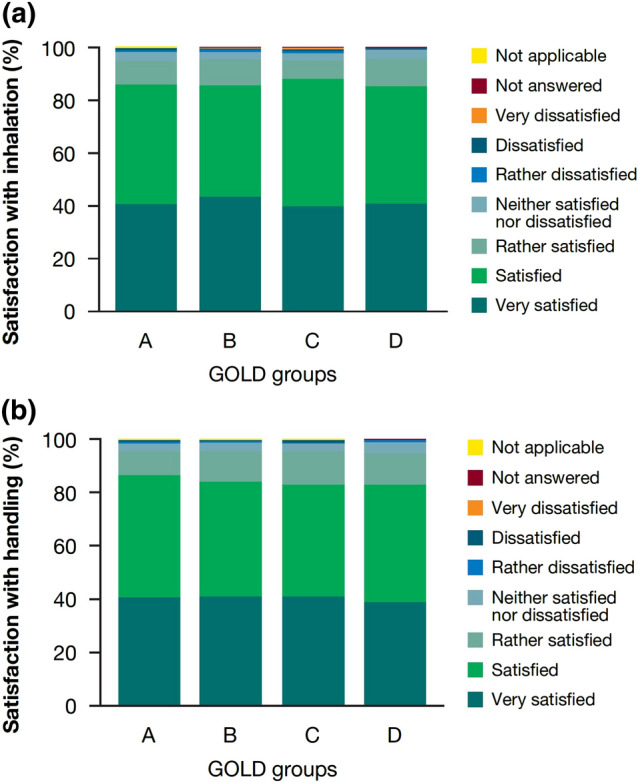

Overall, 85.78% of the pooled population were ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with inhaling tiotropium/olodaterol via the SMI, with 42.04% being very satisfied. Similar trends of inhalation satisfaction were identified among the different GOLD groups (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

a Patient overall satisfaction with inhalation from the Respimat device after week 6. b Patient overall satisfaction with handling of the Respimat device after week 6. ‘Not applicable’ applies to a small percentage of the total population (n = 4 [0.04%]) who did not complete the questionnaire. GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease

In SPIRIT and OTIVACTO, findings were consistent across GOLD 1–4 patients, with most patients ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with inhalation (SPIRIT: GOLD 1: 87.13%, GOLD 2: 88.41%, GOLD 3: 88.59%, GOLD 4: 81.01%; OTIVACTO: GOLD 1: 87.61%, GOLD 2: 86.97%, GOLD 3: 84.49%, GOLD 4: 80.51%). Similar results with regard to being ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with inhalation were seen in maintenance-naïve (SPIRIT: 87.58%; OTIVACTO: 85.58%) and pretreated patients (SPIRIT: 87.30%; OTIVACTO: 84.84%).

Handling Satisfaction

At visit 2, 84.33% of the pooled population were ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with the handling of the tiotropium/olodaterol SMI; 41.02% were ‘very satisfied’. Similar trends in handling satisfaction were shown across GOLD groups A–D in the pooled population (Fig. 1b).

In SPIRIT and OTIVACTO, most GOLD 1–4 patients were ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with device handling (SPIRIT: GOLD 1: 86.14%, GOLD 2: 86.44%, GOLD 3: 84.41%, GOLD 4: 79.11%; OTIVACTO: GOLD 1: 90.26%, GOLD 2: 85.43%, GOLD 3: 83.13%, GOLD 4: 80.51%). Similar results (‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’) with regard to device handling were seen in maintenance-naïve (SPIRIT: 84.94%; OTIVACTO: 84.14%) and pretreated patients (SPIRIT: 85.94%; OTIVACTO: 84.19%).

Patient Adherence and Post-study Continuation

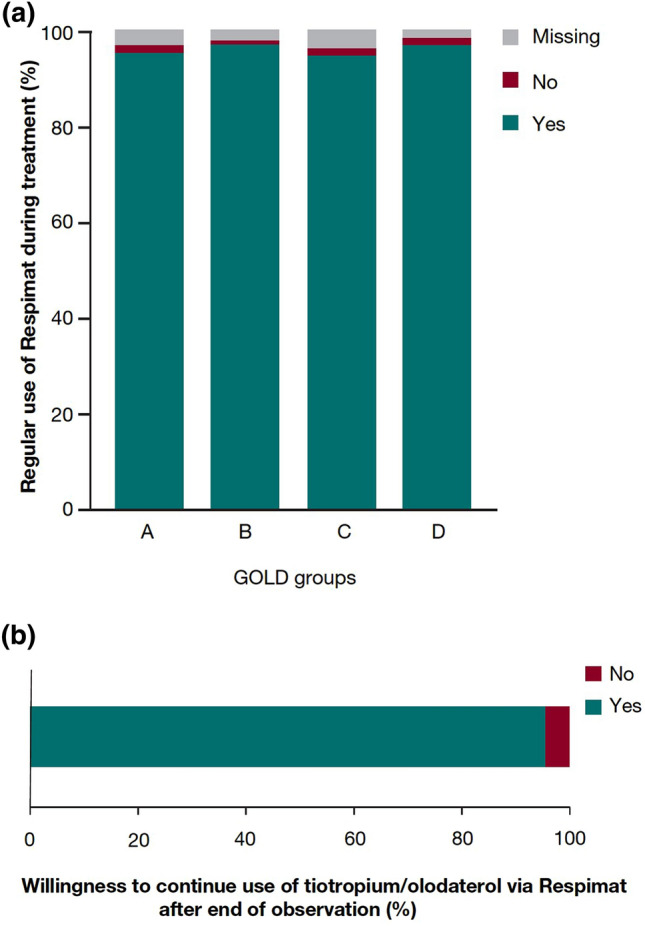

Following self-reporting by the patients, physician-reported patient adherence was high with dual bronchodilation, with 98.57% of patients regularly using their tiotropium/olodaterol SMI (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

a Regular use of Respimat during treatment. b Patients reporting continued use of Respimat after end of observation. GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease

At the end of the observation period, 95.45% of patients in the pooled cohort reported continued use of their tiotropium/olodaterol SMI (Fig. 2b).

Discussion

This post hoc analysis of the SPIRIT and OTIVACTO studies [20, 21] included over 9000 patients with COPD. Following 6 weeks of treatment, most patients were ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with inhalation and handling of the SMI; physician-reported patient adherence was also high. The reported findings were consistent between the different GOLD groups, suggesting that the SMI is well perceived by patients across a range of severities. Furthermore, most patients in our study continued to use the SMI after the study concluded.

Higher patient satisfaction and correct use of their COPD drug-delivery inhaler are important factors in treatment adherence and significant predictors of more favourable clinical outcomes [5, 11, 23]. Khurana et al. suggested that the ability to handle and use the device is one of the three main characteristics that determine drug deposition into the lungs, alongside technical characteristics of the device and the drug formulation [24]. Ineffective inhaler technique, potentially due to poor training when prescribed [25], can influence patient adherence and the perception of device performance, often based on the patient’s beliefs about inhaler medication [26].

Patient satisfaction survey data in COPD suggest that patients who are satisfied with their inhalers show increased adherence to therapy [27, 28]. Using the Patient Satisfaction and Preference Questionnaire scale of satisfaction (ranging from 1 to 7), Miravitlles et al. found that patients rated the Respimat and Breezhaler as 6.0 and 5.9 respectively, indicating satisfaction with these inhalers [27].

This post hoc study has a number of potential limitations. Here, we did not objectively assess error rates when using the inhalers, which would require a validated metric and definition of critical errors to assess incorrect use [6]. Indeed, assessing critical errors can be flawed and sometimes misleading: one study that specifically looked at the tiotropium/olodaterol SMI included errors that are not applicable to the device [29]. A further limitation may be that patients were assessed in our analysis over a relatively short time period using subjective, self-reported metrics. We did not formally monitor adherence by dose-counting and relied on patient reporting of adherence. This is partially because the dose indicator on the Respimat disposable device provides an approximate guide for how much medication is left in the device, not a dose-by-dose count. Additionally, these data suggest high satisfaction with the reusable Respimat; however, as these non-interventional trials did not include a comparator/control group, we are unable to report relative satisfaction versus other inhalers, limiting our conclusions. Finally, data on previous devices were not collected in the SPIRIT and OTIVACTO studies; as such, we are unable to assess patient satisfaction by prior device use.

Nevertheless, the current analysis included a large patient population across different GOLD groups and on different baseline therapies. The non-interventional studies included in this analysis may also provide insight that is closer to the real-world environment than stricter randomised trials.

Both the SPIRIT and OTIVACTO trials used the disposable Respimat device, but following patient feedback, an improved tiotropium/olodaterol SMI has since been developed [11, 30]. This reusable device allows patients to replace used cartridges with new cartridges for 3–6 months, reducing the overall carbon footprint [31]. A market research analysis including 100 patients in Germany (50 currently using dry-powder inhalers and 50 currently using the disposable SMI) asked patients to rate the reusable SMI using the Patient Satisfaction and Preference Questionnaire [32]. After demonstration of the new device, 85% of patients reported they were ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with it, supporting our and others’ findings of high patient satisfaction with SMIs [12, 33].

Conclusions

In this study, over 9000 patients (> 95% of assessed patients) across different GOLD groups reported high satisfaction with respect to inhalation and handling of the Respimat SMI. Treating physicians also reported patient adherence and post-study continuation as high, with patients regularly using their Respimat SMI to control their disease after the end of the observation period.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Support for this project and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee were funded by Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

The authors would like to thank all the participants for taking part in these studies, and their investigators. The authors also extend thanks to Anke Kondla (Boehringer Ingelheim Germany) for advice and study support, and Paul Todd PhD (MediTech Media, UK) for medical writing assistance, in the form of the preparation and revision of the draft manuscript under the authors’ direction and feedback, supported financially by Boehringer Ingelheim.

Authorship

The authors meet the criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. They take full responsibility for the scope, direction, content of, and editorial decisions relating to the manuscript, were involved at all stages of development and have approved the submitted manuscript. The authors received no compensation related to the development of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Christian Taube has nothing to disclose. Valentina Bayer and Christoph Michael Zehendner are both employees of Boehringer Ingelheim. Arschang Valipour reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Novartis, Menarini and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work, as well as other fees from Boehringer Ingelheim during the conduct of the study.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Both the SPIRIT® (NCT02675517) and OTIVACTO® (NCT02719639) studies were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, International Conference on Harmonisation Harmonised Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice and local regulations. The protocols were approved by the authorities and the ethics committees of the respective institutions (SPIRIT, State Medical Council of Baden-Württemberg on 16 October 2015, accepted on 3 November 2015; amended observational plan accepted 27 January 2016; OTIVACTO took place in the following countries: Russia, Romania, Hungary, Austria, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Israel, Slovakia and Switzerland, approval in each of these countries was obtained from the relevant ethical board by 16 November 2016), and signed informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Prior Presentation

Some of these data have been presented in part as a poster at the American Thoracic Society (ATS) International Conference 17–22 May 2019, Dallas, Texas, USA.

Data Availability

The aggregated data set used and analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

Footnotes

Digital Features

To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12794426.

References

- 1.Lopez-Campos JL, Calero C, Quintana-Gallego E. Symptom variability in COPD: a narrative review. Int J Chronic Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2013;8:231–238. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S42866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2020 report). 2019. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/GOLD-2020-REPORT-ver1.0wms.pdf. Cited 15 June 2020.

- 3.Lavorini F, Janson C, Braido F, Stratelis G, Løkke A. What to consider before prescribing inhaled medications: a pragmatic approach for evaluating the current inhaler landscape. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2019;13:1753466619884532. doi: 10.1177/1753466619884532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miravitlles M, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Alcázar B, Viejo JL, García-Río F. Factors affecting the selection of an inhaler device for COPD and the ideal device for different patient profiles. Results of EPOCA Delphi consensus. Pulmon Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Palen J, Ginko T, Kroker A, et al. Preference, satisfaction and errors with two dry powder inhalers in patients with COPD. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2013;10(8):1023–1031. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2013.808186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Usmani OS, Lavorini F, Marshall J, et al. Critical inhaler errors in asthma and COPD: a systematic review of impact on health outcomes. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0710-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duarte-de-Araujo A, Teixeira P, Hespanhol V, Correia-de-Sousa J. COPD: analysing factors associated with a successful treatment. Pulmonology. 2020;26(2):66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2019.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanduzzi A, Balbo P, Candoli P, et al. COPD: adherence to therapy. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2014;9(1):60. doi: 10.1186/2049-6958-9-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghosh S, Pleasants RA, Ohar JA, Donohue JF, Drummond MB. Prevalence and factors associated with suboptimal peak inspiratory flow rates in COPD. Int J Chronic Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:585–595. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S195438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson P. Use of Respimat Soft Mist inhaler in COPD patients. Int J Chronic Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2006;1(3):251–259. doi: 10.2147/copd.2006.1.3.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhand R, Eicher J, Hansel M, Jost I, Meisenheimer M, Wachtel H. Improving usability and maintaining performance: human-factor and aerosol-performance studies evaluating the new reusable Respimat inhaler. Int J Chronic Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:509–523. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S190639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalby RN, Eicher J, Zierenberg B. Development of Respimat® Soft Mist Inhaler and its clinical utility in respiratory disorders. Med Devices (Auckl, NZ) 2011;4:145–155. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S7409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sorino C, Negri S, Spanevello A, Visca D, Scichilone N. Inhalation therapy devices for the treatment of obstructive lung diseases: the history of inhalers towards the ideal inhaler. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;75:15–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casaburi R, Mahler DA, Jones PW, et al. A long-term evaluation of once-daily inhaled tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(2):217–224. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00269802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Donnell DE, Fluge T, Gerken F, et al. Effects of tiotropium on lung hyperinflation, dyspnoea and exercise tolerance in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(6):832–840. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00116004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buhl R, Maltais F, Abrahams R, et al. Tiotropium and olodaterol fixed-dose combination versus mono-components in COPD (GOLD 2–4) Eur Respir J. 2015;45(4):969–979. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00136014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferguson GT, Karpel J, Bennett N, et al. Effect of tiotropium and olodaterol on symptoms and patient-reported outcomes in patients with COPD: results from four randomised, double-blind studies. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27(1):7. doi: 10.1038/s41533-016-0002-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nici L, Mammen MJ, Charbek E, et al. Pharmacologic management of COPD: an official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(9):e56–e69. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0625ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management. 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng115/chapter/Recommendations#ftn.footnote_3. Cited 15 June 2020. [PubMed]

- 20.Valipour A, Tamm M, Kociánová J, et al. Improvement of self-reported physical functioning with tiotropium/olodaterol in Central and Eastern European COPD patients. Int J Chronic Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:2343–2354. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S204388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steinmetz KO, Abenhardt B, Pabst S, et al. Assessment of physical functioning and handling of tiotropium/olodaterol Respimat® in patients with COPD in a real-world clinical setting. Int J Chronic Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:1441–1453. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S195852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2017. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/wms-GOLD-2017-FINAL.pdf. Cited 15 June 2020.

- 23.López-Campos JL, Quintana Gallego E, Carrasco HL. Status of and strategies for improving adherence to COPD treatment. Int J Chronic Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:1503–1515. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S170848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khurana AK, Dubey K, Goyal A, Pawar KS, Phulwaria C, Pakhare A. Correcting inhaler technique decreases severity of obstruction and improves quality of life among patients with obstructive airway disease. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2019;8(1):246–250. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_259_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pothirat C, Chaiwong W, Phetsuk N, Pisalthanapuna S, Chetsadaphan N, Choomuang W. Evaluating inhaler use technique in COPD patients. Int J Chronic Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1291–1298. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S85681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duarte-de-Araujo A, Teixeira P, Hespanhol V, Correia-de-Sousa J. COPD: misuse of inhaler devices in clinical practice. Int J Chronic Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:1209–1217. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S178040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miravitlles M, Montero-Caballero J, Richard F, et al. A cross-sectional study to assess inhalation device handling and patient satisfaction in COPD. Int J Chronic Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:407–415. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S91118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chrystyn H, Small M, Milligan G, Higgins V, Gil EG, Estruch J. Impact of patients' satisfaction with their inhalers on treatment compliance and health status in COPD. Respir Med. 2014;108(2):358–365. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Navaie M, Dembek C, Cho-Reyes S, Yeh K, Celli BR. Device use errors with soft mist inhalers: a global systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Chronic Respir Dis. 2020;17:1479973119901234. doi: 10.1177/1479973119901234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wachtel H, Kattenbeck S, Dunne S, Disse B. The Respimat® development story: patient-centered innovation. Pulmon Ther. 2017;3:19–30. doi: 10.1007/s41030-017-0040-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hänsel M, Bambach T, Wachtel H. Reduced environmental impact of the reusable Respimat® Soft Mist™ inhaler compared with pressurised metered-dose inhalers. Adv Ther. 2019;36(9):2487–2492. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-01028-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forster A, Sauer R, Mattiucci-Gühlke M, Berneburg J. Assessment of patient satisfaction and preference with the Respimat®. Pneumologie. 2020;74(S 01):P537. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schurmann W, Schmidtmann S, Moroni P, Massey D, Qidan M. Respimat Soft Mist inhaler versus hydrofluoroalkane metered dose inhaler: patient preference and satisfaction. Treat Respir Med. 2005;4(1):53–61. doi: 10.2165/00151829-200504010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The aggregated data set used and analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.