Abstract

This research explores the role of materialism, and social comparison to brand addiction in relation to compulsive buying. A structural equation modeling was used to analyze data through partial least squares by collecting online data in Vietnam. The research findings explain social comparison is an antecedent leading to addictive behavior. Materialism mediates and increases the addictive behavior when consumers are significantly impacted by social comparison. In addition, brand addiction leads to word-of-mouth and willingness to pay premium price when consumers are set under social comparison and materialistic tendency. The managerial and theoretical application is also provided in this research.

Keywords: Consumer-brand relationships, Brand addiction, Social comparison, Materialism, Marketing, Consumer attitude, Personality, Individual differences, Interpersonal relations

Consumer-brand relationships; Brand addiction; Social comparison; and Materialism; Marketing; Consumer attitude; Personality; Individual differences; Interpersonal relations

1. Introduction

The brand relationships have been explored through brand constructs such as brand trust (Delgado-Ballester and Luis Munuera-Alemán, 2001), brand commitment (Warrington and Shim, 2000), brand loyalty (Chaudhuri and Holbrook, 2001), or brand love (Batra et al., 2012). Brands identify the consumers' image, as well as show the consumers' identification to others (Kuenzel and Vaux Halliday, 2008, p. 1), and play a key role in consumer's behavior (Carroll and Ahuvia, 2006). Consumers strongly bond with the preferred brand (Park et al., 2008), which is the cause of the overlapping brand identity (Tuškej et al., 2013). Both brand love and brand attachment demonstrate the affective connection between the brand and consumers (Carroll and Ahuvia, 2006; Park et al., 2010). Brand relationships become more intensified and tighten consumers' loyalty, causing the compulsive urge and debt tolerance to possess the collection of any new brand products (Cui et al., 2018). Brand addiction (BA) covers a higher degree of loyalty, commitment, and mental behavior (Mourad, 2015; Mrad and Cui, 2017b).

Brand addiction (BA) is a new brand construct, which refers to consumers' addictive behavior, with consumers particularly loving the brand, and compulsively buying the brand's products (Cui et al., 2018; Weinstein et al., 2016). Their intensive emotions and thinking are always toward the brand (Das et al., 2019). Brand addiction has been proved to promote a higher degree in loyalty compared to other brand constructs (Estevez et al., 2017; Flores, 2004). However, the potential factors predicting brand addiction and the behavioral consequences of this construct are still lacking (Mrad and Cui, 2017a, Mrad and Cui, 2017b). It is important to predict potential factors scaling up to an intensively emotional degree. Materialism is the key feature causing compulsive buying (Reeves et al., 2012), which a dimension of brand addiction (Mrad and Cui, 2020). In addition, social comparison urges consumers to possess more brands or trendy products to insist on their social class (Phua et al., 2017). Social comparison can influence an individual's tendency to compulsive purchase by managing negative influence or accomplishing a self-attractiveness (Liu et al., 2019). The connection between social comparison and materialism is shown through the specific compulsive buying feature of brand addiction. Therefore, brand addiction may lead to willingness to purchase behavior cause of the compulsive buying urges. Under the social comparison impact, and hedonic value tendency, loyal consumers normally tend to spread positive word-of-mouth to their closed community (Amaro et al., 2020; Coelho et al., 2019). The influence of the relationship between consumers toward their addictive brands remains a question, though. This research will figure out the key antecedents and consequences of brand addiction, adding a new understanding of brand addiction.

Vietnam was chosen as the research context of this study. As an emerging market, Vietnam is a quick economic growth since 2002 and a booming middle class (Ralph, 2017), thus people are getting richer and spending more. People in that group earn at least over $700 per month, and this middle class will double by 2020 to 33 million, that means the great potential consumption. Vietnam also has a tiny sliver (less than 2%) of the very rich, calling the upper middle class (Yew Lim et al., 2016). Despite the extensive research on materialism, and addictive purchasing behavior toward the favorable in developed nations, no study can be found on the topic of materialism and brand addiction in Vietnam.

To fill this research gap, the present study makes several important contributions to the existing literature. First, we propose a conceptual model based on existing literature to explore the reasons for brand addiction and materialism behavior. Second, we extend the scope of the literature by testing and validating the conceptual model by involving various social comparison (SC) and word-of-mouth (WOM), and willingness to pay (WTP) of brand addiction. Third, we focus on materialism as a possible mediator between social comparison and brand addiction among Vietnamese consumers.

2. Consumer–brand relationships

This section defines the main concept of brand addiction and introduces the relational constructs in the model.

2.1. Brand addiction

Brand addiction is defined as “a consumer's psychological state that involves mental and behavioral pre-occupation with a particular brand driven by uncontrollable urges to possess the brand's products, involving positive affectivity and gratification” (Mrad and Cui, 2017b, p. 7). The Cambridge dictionary defines addiction as “the need or strong desire to do or to have something, or a very strong liking for something which is an inability to stop doing or using something.” Habitual behavior displays a positive relationship of previous and current consumption. Addiction behavior comes when past consumption significantly influences on the present consumption, a strong habit (Becker, 1992). Becker (1992) divided habitual behavior into harmful and beneficial habits. With brand addiction being a procedure of loyalty from low to high degree, partly built on habit and revealing a highly emotional attachment, strong connection, and commitment to rebuying products without considering negative stories, Messinis (1999) indicates the linkage of habit and addiction.

Brand addiction includes “culture of consumerism, materialism, and individualism” (Purdy, 2018). Mrad and Cui (2017b) indicate that consumer self-image congruence leads to brand love and brand addiction, and brand addiction significantly impacts on life happiness because it creates the positive effects on consumers such as weight, outlook. When consumers are satisfied with the brand, this creates resistance to brand switching (Lam et al., 2010). Consumers, especially the elderly ones, are likely to rebuy and actively resist switching brands (Karani and Fraccastoro, 2010). When consumers are addicted to their favorite brand, then they buy more products, attend more brand events. Mrad and Cui (2017a) found that feeling of guilt, appearance esteem, debt attitude, and life happiness are the effects of brand addiction. To figure out the antecedents and consequences of brand addiction, the relational concepts of brand addiction will be considered such as brand passion, brand love, brand loyalty, and brand attachment.

2.2. Relational concepts

Social comparison (SC) refers to individual difference in social comparison (Gibbons and Buunk, 1999; Vogel et al., 2015). High SC personnel is “sensitive to the behavior of others and has a degree of uncertainty about the self, along with interest in reducing self-uncertainty” (Gibbons and Buunk, 1999, p. 138). Women who are high in SC perceive more dimensional closeness with other women in regard to appearance (Buunk et al., 2012). Individuals can use benchmarks to determine their capabilities and find out sources for their inspiration (Johnson and Lammers, 2012). SC and BA both indicate the connection between individuals with a specific community, for example, Apple brand community. Algesheimer et al. (2005) identify the relationship between a brand community's intentions and behaviors and SC. Identification of brand community can lead to positive consequences and better community engagement. Addictive consumers create the difference of identification with others by using products from their favorite because their self-identities overlap with these brand images. Thus, BA and SC may relate to each other. Addictive consumers only focus on the favorite brand, meanwhile, SC people can look at the hot trend, therefore addictive consumers and SC people may be distinct. Predicting the correlation between SC and BA will be conducted in this study.

2.3. Materialism

The term “materialism” refers to possessions, the high-level of consumption of commodities (Belk, 1985; Richins and Dawson, 1992), and a way of life that is based entirely upon material interests. Materialists focus on material needs and desires, and they tend to neglect spiritual matters and, with them achieving a sense of happiness via the number and quality of possessions that they accumulate, the materialism scale thus contains three dimensions: acquisition centrality; acquisition as the pursuit of happiness; and possession-defined success (Belk, 1985; Richins and Dawson, 1992). Addictive consumers tend to increasingly accumulate their favorite brand's products. In this aspect, materialism logically connects to higher purchasing involvement (Browne and Kaldenberg, 1997). As materialists use brands to reduce their feelings of uncertainty in the marketplace (Rindfleisch et al., 2009), materialism can increase the self-brand connection. Materialism is a motivator for shopping, and it positively impacts on the relationship between brand engagement and shopping in both genders (Goldsmith et al., 2011, 2012). Similarly, Podoshen and Andrzejewski (2012) have found that there is a positive relationship between materialism and brand loyalty, impulsive buying, happiness, and success. Therefore, materialism may correlate with brand fanaticism. This research will explore the correlation between the materialism described by Richins and Dawson (1992) and BA.

3. Research hypotheses

Social comparison and addictive consumers both indicate the connection between individuals with a specific community (Chang et al., 2020; Deleuze et al., 2015; Kim, Choi, Qualls and Han, 2008). Algesheimer et al. (2005) identify the relationship between a brand community's intentions and behaviors and social comparison orientation. Identification of brand community can lead to positive consequences and better community engagement (Brodie et al., 2013; Kumar & Kumar, 2020). Addictive consumers create the difference of identification with others by using products from their favorite because their self-identities overlap with the image of these brands (Mrad and Cui, 2020). In addition, SC can create positive affect (Hemphill and Lehman, 1991), and influence what consumers buy (Wood, 1996). Thus, BA and SC may relate to each other. Predicting the correlation between SC and BA will be conducted as follows.

H1:

Social comparison is likely to develop brand addiction.

Consumers react differently with different possessions (Belk, 1984). Materialism indicates a belief that possessions can reduce stress, and bring happiness in life (Richins and Dawson, 1992). With compulsive buying being a key factor of brand addiction (Granero et al., 2016), materialism contributes to enhancing compulsive buying behavior (Manolis and Roberts, 2012), and we conclude that materialistic individuals are likely to increase the addictive behavior with a favorite brand the products of which they increasingly accumulate. In this aspect, materialism logically connects to higher purchasing involvement (Browne and Kaldenberg, 1997), and materialists use brands to reduce their feelings of uncertainty in the marketplace (Rindfleisch et al., 2009). Thus, materialism, which is a motivator for shopping and positively impacts on the relationship between brand engagement and shopping in both genders (Goldsmith et al., 2011, 2012), can increase the self-brand connection. Similarly, Podoshen and Andrzejewski (2012) have found that there is a positive relationship between materialism and brand loyalty, impulsive buying, happiness, and success. Therefore, materialism may correlate with brand addiction. Thus, the findings suggest that there is a linkage to connect materialism, compulsive buying, and brand addiction.

H2:

Materialistic consumers are likely to develop brand addiction.

Brand addiction refers to the strongly emotional connection of consumers (Cui et al., 2018), thus, they easily ignore the brand scandals, or negative information (Lee et al., 2017; Wakefield and Bennett, 2018). Self-identity refers to the selves, identities, and self-schemas that show people's sense of who they are (Belk, 1988; Escalas et al., 2013; Hogg et al., 2000), and strongly builds up self-brand connection through self-brand congruence (Wallace et al., 2017). When being addictive to a brand, consumers like to speak about a lovable brand to others cause of self-brand connection between their self-identity and brand identification (Kemp et al., 2012; Stokburger-Sauer et al., 2012). Addictive consumers always spread positive information through different ways (Kudeshia et al., 2016). Thus, we posit that:

H3:

Brand addiction is positively related to word-of-mouth.

With consumers becoming highly loyal and having a strong emotion to the brand, they are willing to buy more in the future (Aaker and Keller, 1990; Gounaris and Stathakopoulos, 2004). In addition, the connection of the identity also leads addicted consumers to willingness to pay high price to own the product (Levin et al., 2004; Nalbantis et al., 2017). Thus, we posit that:

H4:

Brand addiction is positively related to willingness to pay.

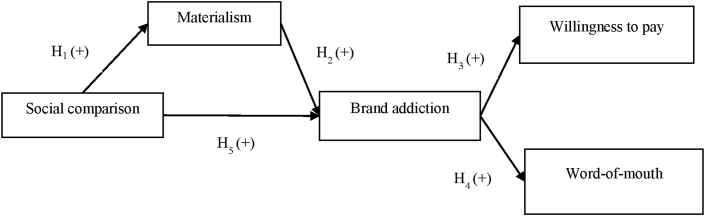

This research seeks to determine whether materialism acts as a mediator social comparison and brand addiction. The mediation effect of materialism and compulsive behavior has been determined by a number of studies of (Nga et al., 2011; Rose, 2007). Compulsive buying and brand addiction have a strong relationship in terms of the shopping desires (Mrad and Cui, 2019). Materialistic consumers are partly caused by the addictive behavior. Buying the favorite brand brings consumers happy and satisfied feelings (Otero-López et al., 2011; Rose, 2007). Social comparison with friends in terms of peer pressure positively predicts materialism (Chan and Prendergast, 2007; Heaney et al., 2005), especially the brand or product is advertised on the media. Both social comparison, and materialism contribute into increasing the addictive behavior (Dittmar, 2005; Yurchisin and Johnson, 2004). Based on the extant literature, materialism is proposed a mediating role between social comparison and brand addiction. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed. Figure 1 depicted the research model.

H5:

Materialism mediates the relationship between social comparison and brand addiction.

Figure 1.

Research model.

4. Methodology

4.1. Data

The questionnaire was pre-tested by 10 respondents and revised accordingly to ensure content validity. All scales either were developed in or translated to Vietnam (translation/back-translation procedure). As a result, the wording of some of the items was modified to improve the clarity of the questions. The sample of comprised 250 respondents in the Vietnam collected via online survey. The screening question was used to identify the target consumers, which is “Do you have a favorite brand?” If the participants answered “Yes”, they were requested to write down the name of the brand. The participants answered all questions taken around 3–5 min. The sample characteristics and data screening are assessed. IBM SPSS Statistics 26 software is used to test the exploratory factor analysis. Finally, data from 236 respondents were used to test the proposed model, with an effective rate of 94.4 per cent, after eliminating extreme values. Following prior research (e.g., Cui et al., 2018; Escalas and Bettman, 2005), respondents were asked to specify a favorite brand name and refer to that brand when answering the survey questions. Respondents were balanced in terms of gender, with 124 males (52.50%) and 110 females (46.6%), and two others (.9%). As for the characteristics of the sample, respondents' ages ranged from 18 to 65 years. A total of 56.4% of respondents were aged between 18 and 25 years. In terms of education, a total of 55.1% of respondents were at vocational certificate, 18.6 % of respondents were at bachelor's degree, and 20.3% of respondents were at post-graduate degree. Finally, respondents' income ranged from 5 million Vietnam Dong (VND) per month up to above 15 million VND per month, with 55.5% earning under 5 million VND per month and 25.4% earning from 5 to 10 million VND per month. Regarding the frequency of favorite brands, the Apple, Adidas, and Samsung are three top brands (33, 20 and 17 per cent, respectively) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic descriptive.

| Variable | Responses | Total number | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Total | 236 | 100% |

| Male | 110 | 46.6% | |

| Female | 124 | 52.5% | |

| Others | 2 | 0.9% | |

| Age | Total | 236 | 100% |

| 18–24 | 133 | 56.4% | |

| 25–35 | 52 | 22% | |

| 36–45 | 45 | 19.1% | |

| Over 45 | 6 | 2.5% | |

| Education | Total | 236 | 100% |

| Primary school | 2 | 0.9% | |

| High school | 12 | 5.1% | |

| Vocational or Trade Certificate | 130 | 55.1% | |

| Associate diploma or Diploma | |||

| Bachelor's degree/Graduate certificate | 44 | 18.6% | |

| Post-graduate Degree (Master, PhD etc.) | 48 | 20.3% | |

| Income | Total | 236 | 100% |

| Under 5 million VND/month | 131 | 55.5% | |

| From 5 to 10 million VND/month | 60 | 25.4% | |

| From 10 million to 15 million VND/month | 21 | 8.9% | |

| Over 15 million VND/month | 24 | 10.2% | |

| Brand name | Total | 236 | 100% |

| Apple | 33 | 14% | |

| Adidas | 20 | 8.5% | |

| Samsung | 17 | 7.2% | |

| Nike | 12 | 5.1% | |

| Zara | 12 | 5.1% | |

| Others | 142 | 65.1% |

4.2. Procedure

To test the theoretical model, scales were adopted from the literature for brand love, brand addiction, obsessive passion, WOM, and WTP. All measures used 7-point scales with the same labels (strongly disagree/disagree/somewhat disagree/neither disagree nor agree/somewhat agree/agree/strongly agree).

Brand addiction was measured with six items from Cui et al. (2018) (e.g., “I tend to give up some life activities and duties such as the occupational, academic, and familial in order to fulfill some activities related to my favorite brand”). Items were averaged to form a brand addiction evaluation index (Cronbach's alpha = .869).

Materialism was measured with six items from Richins and Dawson (1992) (e.g., “I admire people who own expensive homes, cars, and clothes”). Items were averaged to form a materialism evaluation index (Cronbach's alpha = .855).

SC was measured with six items from Allan and Gilbert (1995) (e.g., “In social situation, I sometimes compare my appearance to the appearances of other people”). Items were averaged to form a SC evaluation index (Cronbach's alpha = .874).

WOM was measured with four items from Karjaluoto et al. (2016) (e.g., “I ‘talk up’ my favorite brand to my friends”). Items were averaged to form a WOM evaluation index (Cronbach's alpha = .894).

WTP was measured with three items from Louviere and Islam (2008) (e.g., “My willingness to buy the favorite brand is absolute”). Items were averaged to form a WTP evaluation index (Cronbach's alpha = .874).

5. Results

5.1. Reliability and validity of the measures

The check for discriminant validity between the latent variables including brand addiction, social comparison materialism, WOM, and WTP relied on a more formal test, based covariance structure analysis. For each two above concepts, the sequential tests either allowed the correlation between concepts to be freely estimated or constrained the correlation to equal 1. Table 3 shows the correlation between constructs. The tests confirm that concepts differ, or brand addiction is different with relative concepts.

Table 3.

Reliability and discriminality check.

| CR | AVE | WTP | MA | SC | WOM | BA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WTP | .876 | .703 | .838 | ||||

| MA | .822 | .537 | .566 | .733 | |||

| SC | .872 | .695 | .548 | .453 | .834 | ||

| WOM | .899 | .692 | .663 | .489 | .488 | .832 | |

| BA | .869 | .612 | .755 | .431 | .682 | .777 | .765 |

Notes: CR: Composite Reliability; AVE: Average Variances Extracted. The diagonal scores (in bold) indicate the square root of AVE; BA: Brand addiction, SC: Social comparison, WOM: Word-of-Mouth; WTP: Willingness to pay; MA: Materialism.

We used structural equation modeling (AMOS, 26) to test the fit of our measurement model composed of five latent constructs (materialism, SC, brand addiction, WOM, and willingness to pay). We first tested models, and we found that all items loadings above .50. Next, we tested the fit of the structural model through structural equation modeling (SEM) (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). The data fit the model well (Chi square/df = 2.231, Goodness of fit index (GFI) = .884, comparative fit index (CFI) = .944, tucker lewis index (TLI) = .930, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .002, standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) = .0558). We used partial least square path modeling (PLS) to estimate of the model parameters, which can analyze the distribution freely (Albert et al., 2013). All factor loadings were significant, and all correlations were below .70 (Campbell and Fiske, 1959), indicating configural invariance. We further confirmed that our latent measures exhibited convergent and discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981) (see Tables 2 and 3 for factor loading, average variance extracted, internal consistency, and see Table 4 for Pearson correlations of the measures).

Table 2.

Measurement model.

| Construct | Loading | α |

|---|---|---|

| Brand addiction | .869 | |

| I often fail to control myself from purchasing products of my favorite brand. | 0.723 | |

| I tend to give up some life activities and duties such as the occupational, academic and familial in order to fulfil some activities related to my favorite brand. | 0.657 | |

| I tend to allocate certain portion of my monthly income to buy the products of my favorite brand. | 0.701 | |

| I usually remember tenderly the previous experience with my favorite brand. | 0.747 | |

| I experience a state of impatience immediately before I can get hold of the products of my favorite brand. | 0.765 | |

| I follow my favorite brand's news all the time. | 0.736 | |

| Materialism | .855 | |

| I admire people who own expensive homes, cars, and clothes, | 0.678 | |

| The things I own say a lot about how well I'm doing in life. | 0.771 | |

| I like to own things that impress people. | 0.789 | |

| I like a lot of luxury in my life. | 0.754 | |

| My life would be better if I owned certain things I don't have. | 0.710 | |

| It sometimes bothers me quite a bit that I can't afford to buy all the things I'd like. | 0.771 | |

| Social comparison | .874 | |

| In social situation, I sometimes compare my appearance to the appearances of other people. | 0.856 | |

| I often compare myself with others with respect to what I have accomplished in life. | 0.931 | |

| If I want to learn more about something, I try to find out what others think about it. | 0.871 | |

| I always pay a lot of attention to how I do things compared with how others do things. | 0.847 | |

| I always like to know what others in a similar situation would do. | 0.844 | |

| I often like to talk with others about mutual opinions and experiences. | 0.832 | |

| WOM | .894 | |

| I have recommended my favorite brand to lots of people. | 0.846 | |

| I “talk up” my favorite brand to my friends. | 0.921 | |

| I try to spread the good word about my favorite brand. | 0.915 | |

| I give my favorite brand tons of positive word-of-mouth advertising | 0.802 | |

| Willingness to pay | .874 | |

| The likelihood of my purchasing the favorite brand is willingness. | 0.907 | |

| My willingness to buy the favorite brand is absolute. | 0.921 | |

| The probability that I would consider buying the favorite brand is 100%. | 0.852 |

Notes: All values are significant at the 0.05 level. α = Cronbach's alpha.

Table 4.

Correlations of BA and correlated constructs.

| Correlations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA | SC | WOM | WTP | MA | |

| BA | 1 | .639∗∗ | .645∗∗ | .628∗∗ | .494∗∗ |

| SC | 1 | .524∗∗ | .533∗∗ | .509∗∗ | |

| WOM | 1 | .614∗∗ | .518∗∗ | ||

| WTP | 1 | .537∗∗ | |||

| MA | 1 | ||||

Notes: BA: Brand addiction, SC: Social comparison, WOM: Word-of-Mouth; WTP: Willingness to pay; MA: Materialism; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗p < 0.05.

5.2. Common-method variance

The intercorrelation (IC) scores were below the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) scores, indicating that discriminant validity was achieved. Before testing the research hypotheses, common-method variance was checked. This is because in a study such as this, where data are collected using similar types of response scales (e.g., Likert scales) from the same respondents, common-method variance may pose a problem (Du et al., 2007). Based on previous research, common-method variance was checked using Harman's single-factor test, which suggests that common-method variance poses a problem if (1) a single unrotated factor solution appears from the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) test, or (2) one general factor accounts for the majority of the covariance among the measures. Based on the data, the unrotated factor solution revealed five factors with Eigen values >1. The factor accounts for 37.597% of the total variance, less than 50%. This suggests that common-method variance does not pose a significant problem. There was no general factor in the unrotated structure (Du et al., 2007).

5.3. Hypotheses testing

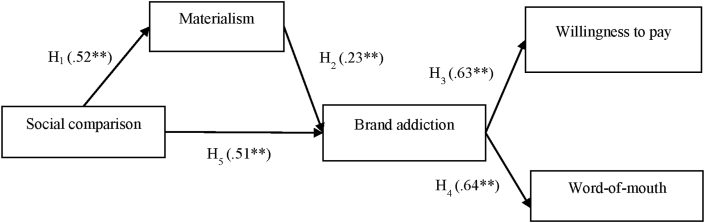

After confirming the reliability and validity of the measures, a bootstrapping procedure (5000 subsamples) was conducted to test the research hypotheses. For this study's purposes, two models were tested: the full mediation model and the partial mediation model. In the partial mediation model, the paths between SC and materialism on brand addiction are available, whereas these paths are not available in the full mediation model. Table 4 shows results of the model and hypotheses testing. As can be seen from the results, brand addiction explains 40.9% and 44.7%, respectively, of the variance in overall materialism in the full and partial mediation model.

To assess the measurement model, we ran multi-group SEM analyses. The fit of measurement model was acceptable (χ2/df (345) = 2.393, CFI = .87, TLI = .86, RMSEA = .08). As predicted in H1, H2 the relationship between SC, materialism and brand addiction was found as statistically significant (β = .64, p < .0001; and β = .49, p < .0001, respectively) and accordingly H1, and H2 are supported. The results also reveal that SC is a better predictor of brand addiction than materialism.

In concert with H3, and H4 brand addiction positively affects willingness to pay premium (β = 0.63, p < 0.001), and word-of-mouth (β = 0.64, p < 0.001) and thereby, H3, and H4 are supported. When consumers display high brand addiction, they display higher propensity to conduct word-of-mouth and willingness to pay premium prices (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Results of the hypotheses testing.

| Hypotheses | Full mediation |

Partial mediation |

Support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPC | SPC | |||

| H1: Social comparison → Brand addiction | .64∗∗∗ | .52∗∗∗ | Supported | |

| H2: Materialism → Brand addiction | .49∗∗∗ | .23∗∗ | Supported | |

| H3: Brand addiction → Willingness to pay premium | .63∗∗∗ | .63∗∗∗ | Supported | |

| H4: Brand addiction → Word-of-mouth | .64∗∗ | .64∗∗ | Supported | |

| H5: Social comparison → Materialism | .51∗∗∗ | Supported | ||

| Variance explained | ||||

| Brand addiction | 40.9% | 44.7% | ||

Notes: SPC = Standardized Path Coefficient; ∗∗∗p < .0001; ∗∗p < .001.

5.4. Mediation via materialism

In order to test H5, the four conditions which were proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986) were followed in consideration of the mediating impact of materialism on the relationship between SC and brand addiction. Those conditions are as follows: there must be a significant relationship (a) between SC and brand addiction (β = 0.52, p < 0.001); (b) between SC and materialism (β = 0.51, p < 0.001); (c) between materialism and brand addiction (β = 0.23, p < 0.001); (d) when investigating the mediating impact of materialism statistically, the existing significant relationship between SC and brand addiction as examined in the first condition (β = 0.64) has been considerably decreased, and becomes statistically insignificant (β = .52, p < 0.001). Therefore, this result specifies a partial mediating impact of materialism on the link between SC and brand addiction (see Table 5 and Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Research model results.

To further test the mediation analysis, we checked the indirect effect and bias-corrected 95% bootstrap confidence interval (CI) from the PLS output. It is suggested that the SEM approach is superior to Baron and Kenny's (1986) approach in testing mediation effect, since it estimates everything simultaneously (Zhao et al., 2010). Firstly, we checked the mediation effect of materialism on SC and brand addiction (see Table 6). The confidence interval for the indirect effect of actual SC and brand addiction excludes zero (95% CI [0.06, 0.19]). The results show that materialism mediates the relationship between SC and brand addiction. The direct effect of SC on impulsive buying is also significant (SPC = .12, p < 0.001) and since a × b × c (0.075) is positive, it is a competitive mediation (Zhao et al., 2010).

Table 6.

Mediating effects of the partial mediation model.

| Hypotheses | Bias-corrected bootstrap 95% confidence interval | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect effect | SE | t-value | Lower | Upper | |

| Social comparison →Materialism→ Brand addiction | .12∗∗∗ | .056 | 9.294 | .06 | .19 |

Notes: Bootstrapping based on n = 5000 subsamples; ∗∗∗p < 0.01; SE: Standard error.

6. Discussion and conclusion

6.1. Theoretical implications

Research on brand addiction is recent, offering limited insights into the antecedents and consequences of this construct. The findings of this study offer initial empirical evidence showing that materialism and SC drive buying behavior of brand addiction. Whereas previous research focused validate the brand addiction scale and assessed the compulsive buying role toward brand addiction (Mrad and Cui, 2017a, Mrad and Cui, 2017b, 2019). The research model tests a nomological network that the features well-established consumer-brand relationship constructs, including both antecedents and consequences of brand addiction. Building on insights about how materialism and SC shape preferences for products by identifying ideal self-congruity as an explanatory factor of their preference for brands by focusing on a product category chosen for both functional and social benefits, we find that materialism and SC are positively associated with brand addiction yet only for brands high in ideal self-congruity.

Recent research on brand addiction focused on figuring out the definition and the scale have not yet offered the antecedents and consequences. Brand addiction's components include bonding, brand exclusiveness, collection, and compulsive urges, which support to identify the specific factors (Mourad, 2015). With findings determining materialism impacts on brand love, the proposed model establishes and tests a nomological network and predicts the antecedents and consequences of brand addiction, which can refer that consumers tending to own expensive homes, cars, or clothes (Kim et al., 2012) will be addictive with the luxury brands in those things (Gil et al., 2012).

Materialism also impacts on compulsive buying (Claes et al., 2016), a dimension of brand addiction (Cui et al., 2018) and this research finding insists that materialism can increase the addictive behavior of loyal consumers and urge them to buy more products, however, previous research has not confirmed that materialism directly leads to brand addiction. In addition, consumers rely heavily on showing their self-definition, and seek their self-image via the brand, and they will be easily obsessed by the favorite brand (Mageau et al., 2009), which links to brand addiction. However, compulsive buying refers a negative aspect of purchasing behavior (Shoham and Brenčič, 2003). Brand addiction was built up from both positive and negative sides. Materialism and compulsive buying indicate the negative aspects, because they control the consumers' mind, and urge them to consume more products, and participate in all brands' events (Wang and Yang, 2008).

Consumers become engaging with the brand when their self-identity overlaps with brand identity (Abarbanel et al., 2018; Harrigan et al., 2018) and SC emphasizes on how other people's views react on the consumer's behavior and their selecting of the brand to show their identity (Auty and Elliot, 1998), which increases the addictive behavior with the brand. SC emphasizes on how other people's views react on the consumer's behavior and their selecting of the brand to show their identity (Auty and Elliot, 1998). SC contributes to strengthening the consumers' commitment with brand cause of the unique identity. Regarding positive sides of brand identity, the unique brand identity makes people stand out from the social community in a positively emotional way. Thus, these research findings can confirm that SC contributes to enhancing the brand addiction.

The findings also emphasize that WOM and willingness to pay are the most popular effects of brand constructs. When the origins of intrinsic motivation of materialism and SC are different, it drives the consumers' behavior following to different ways. As SC is the main motivation urging consumers to connect with the brand identity, they will be willing to pay a premium to buy the products (Kuenzel and Vaux Halliday, 2008), with materialistic consumers always wanting to buy more products to satisfy their buying behavior (Yurchisin and Johnson, 2004), especially of the addictive brand. This urges them to buy more and spread positive information to others (Gounaris and Stathakopoulos, 2004; Kuenzel and Vaux Halliday, 2008).

6.2. Managerial implications

To implicate the theoretical contribution, current findings suggest that brand managers should enhance the hedonic values, and unique features of the brand, which enhance inspiration for loyal consumers. High brand value can build up through quality materials, innovative attributes of products, and inspired advertisement strategies. Band managers can create an idealized image of the brand, then emphasized brand features in advertisements to attract for the consumers.

Regarding the consequences of brand addiction in the relationship with materialism and SC, this result shows that brand addiction tends to effect on WOM more than the WTP. Materialistic consumers seem to positively spread the word to others (Vega-Vázquez et al., 2017), which is the most effective channel to advertise and attract new potential consumers in their network. The unique physical features of products which encourages consumers to be proud of the brand and actively spread the words to their closed community like friends, colleagues.

Along with the improvement of virtual communities, brands should maintain and enhance the interactions with their consumers via social media channels such as brand Instagram, Fan pages, Twitter, and so on. Managers should invite passionate consumers who own a rich brand knowledge and commit with the brand for a long period to share their knowledge, usage experiences within the communities (Jin and Ryu, 2020). This helps to extend the spread WOM and build up the trust of other consumers toward the brand. As a result, consumers will be a willingness to pay more for the products they are trusted with and supported by the communities.

6.3. Limitations and future research

This study also has limitations. First, data was collected in Vietnam, a specific country and culture, cannot generalize the results. In the future, the research could collect data in different countries including both developed and developing countries, which can increase the validity of research findings. Second, this study collects data at a specific point in time, meanwhile, the consumer-brand relationships have changed over time. Thus, the findings cannot generalize the tendency of consumers toward their focal brands during a long period. Future research can conduct the study as longitudinal data, which can provide better findings on addictive consumers' behavior for a certain period.

Next, mainly consumers filled Apple and hi-technology product in the favorite brand, then the findings can represent for Apple Future research may consider the negative aspects of brand addiction, which can provide the warnings for brand managers to be aware and avoid ruining the brand reputation by action of fans. Future research could collect data in a specific brand community, which can see which factors have more effects, and may provide better suggestions in managerial decision making.

Next, brand addiction refers to obsessive passion and causes several negative influences on both consumers and society (Deleuze et al., 2018; Thorne and Bruner, 2006). Materialism and compulsive buying urge consumers without enabling to control their mind (Moschis, 2017; Podoshen and Andrzejewski, 2012). Consumers are easy to fall into debt or bad financial situations (Garðarsdóttir & Dittmar, 2012). Future research can figure out the specific negative impact of brand addiction caused by obsession and compulsive buying features of brand addiction.

Finally, previous study has shown gender or age influences brand perception (Rajeev, 2005), price (Kamineni and O'Cass, 2000). This study does not take the role of control variables to consideration, then future studies should consider these variables for checking the influences. Finally, materialism lead to compulsive buying that may cause negative impact such as financial worry, debt (Garðarsdóttir & Dittmar, 2012), deviation behavior (Moschis, 2017). Future research may explore features leading to the negative aspects of brand addiction, which can provide the warnings for brand managers to be aware and avoid ruining the brand reputation by action of addictive consumers.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

M. Le: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research received the funding from University of Economics Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Aaker D.A., Keller K.L. Consumer evaluations of brand extensions. J. Market. 1990;54(1):27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Abarbanel B., Cain L., Philander K. Influence of perceptual factors of a responsible gambling program on customer satisfaction with a gambling firm. Econ. Bus. Lett. 2018;7(4):144–155. [Google Scholar]

- Albert N., Merunka D., Valette-Florence P. Brand passion: antecedents and consequences. J. Bus. Res. 2013;66(7):904–909. [Google Scholar]

- Algesheimer R., Dholakia U.M., Herrmann A. The social influence of brand community: evidence from European car clubs. J. Market. 2005;69(3):19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Allan S., Gilbert P. A social comparison scale: psychometric properties and relationship to psychopathology. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 1995;19(3):293–299. [Google Scholar]

- Amaro, Barroco, Antunes Exploring the antecedents and outcomes of destination brand love. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J.C., Gerbing D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988;103(3):411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Auty S., Elliot R. Social identity and the meaning of fashion brands. ACR Eur. Adv. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Baron R.M., Kenny D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batra R., Ahuvia A., Bagozzi R.P. Brand love. J. Market. 2012;76(2):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Becker G.S. Habits, addictions, and traditions. Kyklos. 1992;45(3):327–345. [Google Scholar]

- Belk R.W. Three scales to measure constructs related to materialism: reliability, validity, and relationships to measures of happiness. ACR North Am. Adv. 1984 [Google Scholar]

- Belk R.W. Materialism: trait aspects of living in the material world. J. Consum. Res. 1985;12(3):265–280. [Google Scholar]

- Belk R.W. Possessions and the extended self. J. Consum. Res. 1988;15(2):139–168. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie, Ilic, Juric, Hollebeek Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: an exploratory analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2013;66(1):105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Browne B.A., Kaldenberg D.O. Conceptualizing self-monitoring: links to materialism and product involvement. J. Consum. Market. 1997;14(1):31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Buunk A.P., Dijkstra P., Bosch Z.A., Dijkstra A., Barelds D.P.H. Social comparison orientation as related to two types of closeness. J. Res. Pers. 2012;46(3):279–285. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D.T., Fiske D.W. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychol. Bull. 1959;56(2):81–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll B.A., Ahuvia A.C. Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Market. Lett. 2006;17(2):79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Chan K., Prendergast G. Materialism and social comparison among adolescents. SBP (Soc. Behav. Pers.): Int. J. 2007;35(2):213–228. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Hou, Wang, Cui, Zhang Effects of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation on social loafing in online travel communities. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020:106360. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri A., Holbrook M.B. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: the role of brand loyalty. J. Market. 2001;65(2):81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Claes L., Müller A., Luyckx K. Compulsive buying and hoarding as identity substitutes: the role of materialistic value endorsement and depression. Compr. Psychiatr. 2016;68:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, Bairrada, Peres Brand communities’ relational outcomes, through brand love. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- Cui C.C., Mrad M., Hogg M.K. Brand addiction: exploring the concept and its definition through an experiential lens. J. Bus. Res. 2018;87:118–127. [Google Scholar]

- Das, Agarwal, Malhotra, Varshneya Does brand experience translate into brand commitment?: a mediated-moderation model of brand passion and perceived brand ethicality. J. Bus. Res. 2019;95:479–490. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Long, Liu, Maurage, Billieux Passion or addiction? Correlates of healthy versus problematic use of videogames in a sample of French-speaking regular players. Addict. Behav. 2018;82:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Rochat, Romo, Van der Linden, Achab, Thorens…Rothen Prevalence and characteristics of addictive behaviors in a community sample: a latent class analysis. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2015;1:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Ballester E., Luis Munuera-Alemán J. Brand trust in the context of consumer loyalty. Eur. J. Market. 2001;35(11/12):1238–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar H. A new look at “compulsive buying”: self–discrepancies and materialistic values as predictors of compulsive buying tendency. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2005;24(6):832–859. [Google Scholar]

- Du S., Bhattacharya C.B., Sen S. Reaping relational rewards from corporate social responsibility: the role of competitive positioning. Int. J. Res. Market. 2007;24(3):224–241. [Google Scholar]

- Escalas J.E., Bettman J.R. Self-construal, reference groups, and brand meaning. J. Consum. Res. 2005;32(3):378–389. [Google Scholar]

- Escalas, White, Argo, Sengupta, Townsend, Sood, Ward, Broniarczyk, Chan, Berger Self-identity and consumer behavior. J. Consum. Res. 2013;39(5):xv–xviii. [Google Scholar]

- Estevez, Jáuregui, Sanchez-Marcos, López-González, Griffiths Attachment and emotion regulation in substance addictions and behavioral addictions. J. Behav. Addict. 2017;6(4):534–544. doi: 10.1556/2006.6.2017.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores . Jason Aronson; 2004. Addiction as an Attachment Disorder. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell C., Larcker D.F. SAGE Publications Sage CA; Los Angeles, CA: 1981. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Garðarsdóttir, Dittmar The relationship of materialism to debt and financial well-being: the case of Iceland’s perceived prosperity. J. Econ. Psychol. 2012;33(3):471–481. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons F.X., Buunk B.P. Individual differences in social comparison: development of a scale of social comparison orientation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999;76(1):129–142. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil L.A., Kwon K.-N., Good L.K., Johnson L.W. Impact of self on attitudes toward luxury brands among teens. J. Bus. Res. 2012;65(10):1425–1433. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith R.E., Flynn L.R., Clark R.A. Materialism and brand engagement as shopping motivations. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2011;18(4):278–284. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith R.E., Flynn L.R., Clark R.A. Materialistic, brand engaged and status consuming consumers and clothing behaviors. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2012;16(1):102–119. [Google Scholar]

- Gounaris S., Stathakopoulos V. Antecedents and consequences of brand loyalty: an empirical study. J. Brand Manag. 2004;11(4):283–306. [Google Scholar]

- Granero R., Fernández-Aranda F., Steward T., Mestre-Bach G., Baño M., del Pino-Gutiérrez A.…Jiménez-Murcia S. Compulsive buying behavior: characteristics of comorbidity with gambling disorder. Front. Psychol. 2016;7:625. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan P., Evers U., Miles M.P., Daly T. Customer engagement and the relationship between involvement, engagement, self-brand connection and brand usage intent. J. Bus. Res. 2018;88:388–396. [Google Scholar]

- Heaney J.-G., Goldsmith R.E., Jusoh W.J.W. Status consumption among Malaysian consumers: exploring its relationships with materialism and attention-to-social-comparison-information. J. Int. Consum. Market. 2005;17(4):83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hemphill, Lehman Social comparisons and their affective consequences: the importance of comparison dimension and individual difference variables. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1991;10(4):372–394. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, Cox, Keeling The impact of self-monitoring on image congruence and product/brand evaluation. Eur. J. Market. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Ryu “I'll buy what she's# wearing”: the roles of envy toward and parasocial interaction with influencers in instagram celebrity-based brand endorsement and social commerce. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2020;55:102121. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Lammers The powerful disregard social comparison information. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012;48(1):329–334. [Google Scholar]

- Kamineni, O'Cass . 2000. The Effect of Materialism, Gender and Nationality on Consumer Perception of a High Priced Brand. [Google Scholar]

- Karani K.G., Fraccastoro K.A. Resistance to brand switching: the elderly consumer. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2010;8(12) [Google Scholar]

- Karjaluoto H., Munnukka J., Kiuru K. Brand love and positive word of mouth: the moderating effects of experience and price. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2016;25(6):527–537. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp E., Childers C.Y., Williams K.H. Place branding: creating self-brand connections and brand advocacy. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.W., Choi J., Qualls W., Han K. It takes a marketplace community to raise brand commitment: the role of online communities. J. Market. Manag. 2008;24(3–4):409–431. [Google Scholar]

- Kim K.H., Ko E., Xu B., Han Y. Increasing customer equity of luxury fashion brands through nurturing consumer attitude. J. Bus. Res. 2012;65(10):1495–1499. [Google Scholar]

- Kudeshia C., Sikdar P., Mittal A. Spreading love through fan page liking: a perspective on small scale entrepreneurs. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016;54:257–270. [Google Scholar]

- Kuenzel S., Vaux Halliday S.V. Investigating antecedents and consequences of brand identification. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2008;17(5):293–304. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar J., Kumar V. Drivers of brand community engagement. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2020;54:101949. [Google Scholar]

- Lam S.K., Ahearne M., Hu Y., Schillewaert N. Resistance to brand switching when a radically new brand is introduced: a social identity theory perspective. J. Market. 2010;74(6):128–146. [Google Scholar]

- Lee W.-I., Cheng S.-Y., Shih Y.-T. Effects among product attributes, involvement, word-of-mouth, and purchase intention in online shopping. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2017;22(4):223–229. [Google Scholar]

- Levin A.M., Beasley F., Gamble T. Brand loyalty of NASCAR fans towards sponsors: the impact of fan identification. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2004;6(1) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, He, Li Upward social comparison on social network sites and impulse buying: a moderated mediation model of negative affect and rumination. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019;96:133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Louviere J.J., Islam T. A comparison of importance weights and willingness-to-pay measures derived from choice-based conjoint, constant sum scales and best–worst scaling. J. Bus. Res. 2008;61(9):903–911. [Google Scholar]

- Mageau G.A., Vallerand R.J., Charest J., Salvy S.J., Lacaille N., Bouffard T., Koestner R. On the development of harmonious and obsessive passion: the role of autonomy support, activity specialization, and identification with the activity. J. Pers. 2009;77(3):601–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolis C., Roberts J.A. Subjective well-being among adolescent consumers: the effects of materialism, compulsive buying, and time affluence. Appl. Res. Qual. Life. 2012;7(2):117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Messinis G. Habit formation and the theory of addiction. J. Econ. Surv. 1999;13(4):417–442. [Google Scholar]

- Mourad M.W. University of Manchester; Manchester: 2015. Brand Addiction: A New Concept, its Measurement Scale and a Theoretical Model. [Google Scholar]

- Moschis Research frontiers on the dark side of consumer behaviour: the case of materialism and compulsive buying. J. Market. Manag. 2017;33(15-16):1384–1401. [Google Scholar]

- Mrad M., Cui C. Springer; Berlin: 2017. The Roles of Brand Addiction in Achieving Appearance Esteem and Life Happiness in Fashion Consumption: an Abstract Marketing at the confluence between Entertainment and Analytics; pp. 1269–1270. [Google Scholar]

- Mrad M., Cui C.C. Brand addiction: conceptualization and scale development. Eur. J. Market. 2017;51(11/12):1938–1960. [Google Scholar]

- Mrad M., Cui C.C. Comorbidity of compulsive buying and brand addiction: an examination of two types of addictive consumption. J. Bus. Res. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- Mrad, Cui Comorbidity of compulsive buying and brand addiction: an examination of two types of addictive consumption. J. Bus. Res. 2020;113:399–408. [Google Scholar]

- Nalbantis G., Pawlowski T., Coates D. The fans’ perception of competitive balance and its impact on willingness-to-pay for a single game. J. Sports Econ. 2017;18(5):479–505. [Google Scholar]

- Nga J.K., Yong L.H., Sellappan R. Young Consumers; 2011. The Influence of Image Consciousness, Materialism and Compulsive Spending on Credit Card Usage Intentions Among Youth. [Google Scholar]

- Otero-López J.M., Pol E.V., Bolaño C.C., Mariño M.J.S. Materialism, life-satisfaction and addictive buying: examining the causal relationships. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2011;50(6):772–776. [Google Scholar]

- Park C.W., MacInnis D.J., Priester J. Brand attachment: constructs, consequences, and causes. Found. Trends® Microecon. 2008;1(3):191–230. [Google Scholar]

- Park C.W., MacInnis D.J., Priester J., Eisingerich A.B., Iacobucci D.J. Brand attachment and brand attitude strength: conceptual and empirical differentiation of two critical brand equity drivers. J. Market. 2010;74(6):1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Phua, Jin, Kim Gratifications of using facebook, twitter, instagram, or snapchat to follow brands: the moderating effect of social comparison, trust, tie strength, and network homophily on brand identification, brand engagement, brand commitment, and membership intention. Telematics Inf. 2017;34(1):412–424. [Google Scholar]

- Podoshen J.S., Andrzejewski S.A. An examination of the relationships between materialism, conspicuous consumption, impulse buying, and brand loyalty. J. Market. Theor. Pract. 2012;20(3):319–334. [Google Scholar]

- Purdy L. Russell Publishing; Brand, Germany: 2018. We’re All on the Sacle of Addiction.https://www.positive.news/society/were-all-on-the-scale-of-addiction/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Ralph J. Forbes; 2017. The 5 Engines that Guarantee Vietnam More Fast Economic Growth This Year.https://www.forbes.com/sites/ralphjennings/2017/01/05/beer-to-xx-5-reasons-vietnams-economy-will-grow-quickly-this-year/#3f4a339f1e85 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, Baker, Truluck Celebrity worship, materialism, compulsive buying, and the empty self. Psychol. Market. 2012;29(9):674–679. [Google Scholar]

- Richins M.L., Dawson S. A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: scale development and validation. J. Consum. Res. 1992;19(3):303–316. [Google Scholar]

- Rajeev K. Influence of materialism, gender and nationality on consumer brand perceptions. J. Target Meas. Anal. Market. 2005;14(1):25. [Google Scholar]

- Rindfleisch A., Burroughs J.E., Wong N. The safety of objects: materialism, existential insecurity, and brand connection. J. Consum. Res. 2009;36(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rose P. Mediators of the association between narcissism and compulsive buying: the roles of materialism and impulse control. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2007;21(4):576. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoham A., Brenčič M.M. Compulsive buying behavior. J. Consum. Market. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Stokburger-Sauer N., Ratneshwar S., Sen S. Drivers of consumer–brand identification. Int. J. Res. Market. 2012;29(4):406–418. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, Bruner An exploratory investigation of the characteristics of consumer fanaticism. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2006;9(1):51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Tuškej U., Golob U., Podnar K. The role of consumer–brand identification in building brand relationships. J. Bus. Res. 2013;66(1):53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Vázquez, Castellanos-Verdugo, Oviedo-García Shopping value, tourist satisfaction and positive word of mouth: the mediating role of souvenir shopping satisfaction. Curr. Issues Tourism. 2017;20(13):1413–1430. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel E.A., Rose J.P., Okdie B.M., Eckles K., Franz B. Who compares and despairs? The effect of social comparison orientation on social media use and its outcomes. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2015;86:249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield L.T., Bennett G. Sports fan experience: electronic word-of-mouth in ephemeral social media. Sport Manag. Rev. 2018;21(2):147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, Buil, de Chernatony Consumers’ self-congruence with a “liked” brand. Eur. J. Market. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.-C., Yang H.-W. Passion for online shopping: the influence of personality and compulsive buying. SBP (Soc. Behav. Pers.): Int. J. 2008;36(5):693–706. [Google Scholar]

- Warrington P., Shim S. An empirical investigation of the relationship between product involvement and brand commitment. Psychol. Market. 2000;17(9):761–782. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, Maraz, Griffiths, Lejoyeux, Demetrovics . Neuropathology of Drug Addictions and Substance Misuse. Elsevier; 2016. Compulsive buying—features and characteristics of addiction; pp. 993–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Wood What is social comparison and how should we study it? Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1996;22(5):520–537. [Google Scholar]

- Yew Lim M.J., Walters Jeff, Wu Emily, Wastuwidyaningtyas Brigitta. 2016. Globalization, Innovation and Product Development. [Google Scholar]

- Yurchisin J., Johnson K.K. Compulsive buying behavior and its relationship to perceived social status associated with buying, materialism, self-esteem, and apparel-product involvement. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2004;32(3):291–314. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Lynch J.G., Jr., Chen Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010;37(2):197–206. [Google Scholar]