Abstract

While expression of ribosomal protein genes (RPGs) in the budding yeast has been extensively studied, a longstanding enigma persists regarding their co-regulation under fluctuating growth conditions. Most RPG promoters display one of two distinct arrangements of a core set of transcription factors (TFs) and are further differentiated by the presence or absence of the HMGB protein Hmo1. However, a third group of promoters appears not to be bound by any of these proteins, raising the question of how the whole suite of genes is co-regulated. We demonstrate here that all RPGs are regulated by two distinct, but complementary mechanisms driven by the TFs Ifh1 and Sfp1, both of which are required for maximal expression in optimal conditions and coordinated downregulation upon stress. At the majority of RPG promoters, Ifh1-dependent regulation predominates, whereas Sfp1 plays the major role at all other genes. We also uncovered an unexpected protein homeostasis-dependent binding property of Hmo1 at RPG promoters. Finally, we show that the Ifh1 paralog Crf1, previously described as a transcriptional repressor, can act as a constitutive RPG activator. Our study provides a more complete picture of RPG regulation and may serve as a paradigm for unravelling RPG regulation in multicellular eukaryotes.

INTRODUCTION

Ribosome biogenesis, one of the most energy consuming processes in all organisms, is a major driver of rapid cell growth (1,2). Ribosome production rates are estimated to be about 2–4000 per minute in actively dividing budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae; hereafter yeast) and human cells, respectively. This intensive and complex production process involves several hundred ribosome biogenesis (RiBi) factors that direct the hierarchical assembly onto rRNA of the ribosomal proteins (RPs), which themselves constitute ∼50% of total protein copy number and ∼30% of protein mass in yeast. Regulated production of stoichiometric numbers of RPs is important in all organisms to maintain a functional proteome, as demonstrated by the discovery of specific mechanisms that prevent accumulation of unassembled RPs in both yeast and mammalian cells (3–7). Dysregulation of ribosome biogenesis is also associated with cancer and a group of human diseases called ribosomopathies, some of which are caused by RPG haplo-insufficiency (8). Understanding how cells produce roughly equimolar amounts of RPs in stress and non-stress conditions remains an open question of fundamental interest.

Most of our detailed knowledge on the expression of RPGs in eukaryotes is derived from studies of yeast, whose ribosomes contain 79 distinct RPs encoded by 138 RPGs, of which 20 are encoded by unique RPGs and 118 by duplicated genes. Yeast cells are highly sensitive to gene dosage of RPGs, suggesting that RPG mRNA levels need to be tightly controlled (9). Since most RPGs exist as duplicated copies, cells have developed specific regulatory mechanisms to produce RPs in roughly equimolar quantities (10). One of these mechanisms is encoded within their promoters by specific DNA sequences that facilitate or disfavour transcription, such that expression of single-copy RPGs is similar to that of the sum of duplicated paralogues (11). Pre-mRNA splicing, mRNA decay, translation control and protein turnover provide additional layers of complexity that may act to maintain steady-state levels of ribosome components (2,6,12).

Transcription of RPGs in yeast is tightly linked to cell growth, suggesting that TF binding at their promoters might be highly sensitive to stress and nutrient conditions. Consistent with this notion, inhibition of the Target Of Rapamycin Complex 1 (TORC1) kinase, a major transducer of nutrient signals, leads to rapid cytoplasmic re-localization of the growth-promoting TF Sfp1 and release of the TF Ifh1 from RPG promoters (13–22). Although Sfp1 can increase or decrease RPG expression according to growth conditions, Sfp1 is mainly involved in regulation of RiBi genes (23,24), whereas the transcription factor Ifh1 is the primary regulator for RPG transcription. Ifh1 binds almost exclusively to RPGs promoters (21), indicating that cells have developed a dedicated mechanism to regulate RPG expression. We showed previously that Ifh1 binding is directly linked to RNA Polymerase I (RNAPI) activity, and to levels of unassembled RPs in the nucleus, which allows cells to align RPG expression to both rRNA production and ribosome assembly, respectively (3,13). The existence of these two mechanisms highlights the requirement for cells to develop specific processes for the maintenance of stoichiometric production of ribosome components.

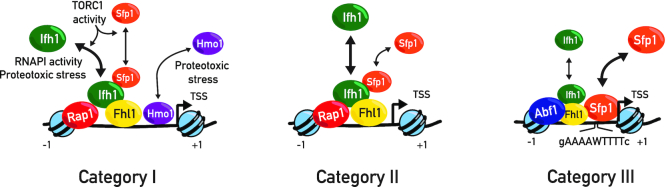

How RPG co-regulation is achieved in S. cerevisiae still remains poorly understood since their promoters display a heterogeneous organization typically divided into two major categories (Category I and Category II; Cat I and Cat II from hereon), both bound by the TFs Rap1, Fhl1 and Ifh1, and differentiated by the presence or absence of the High Mobility Group B (HMGB) protein Hmo1 (16,21,22,25–29). In addition, the existence of a third category of RPG promoters (Cat III), apparently devoid of any transcription factors shared by the other two groups, constitutes one of the major obstacles in the complete understanding of mechanisms that allow RPG co-regulation. Only the general regulatory factor (GRF) Abf1, absent at other RPG promoters, is detected by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) at the promoters of these genes (30,31). Consequently, it was suggested that these Cat III genes are expressed independently of the other RPGs (28), thus raising the question of how the ensemble of RPGs could be co-regulated. Moreover, Crf1, a paralogue of Ifh1, has been reported to repress RPGs upon stress (18), but this mechanism seems not to operate in the widely used W303 strain background (32).

In this study, we elucidate the common logic of the RPG regulatory network by evaluating both the architecture and activity of promoters under conditions of stress or modulation of TF levels. We uncovered an unexpected feature of the Ifh1 paralog, Crf1, which can act as a constitutively active version of Ifh1 in the W303 background, when overexpressed. Furthermore, we found that Hmo1 binding at RPGs is highly sensitive to proteotoxic stress. Importantly, we identified the TFs regulating the activity of the Cat III promoters, which lack Rap1 binding. Our findings demonstrate that RPG co-regulation requires the complementary action of two different mechanisms, one involving Ifh1 and the other using Sfp1. The combination of these two mechanisms is required to rapidly coordinate the activity of the heterogeneously constituted RPG promoters upon stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and growth conditions

The experiments presented in this study were performed using the budding yeast S. cerevisiae. A complete list of strains and plasmids used is provided in Supplementary Tables S7 and S8, respectively. Strains were generated by genomic integration of tagging or disruption cassettes as described (33,34). Yeast cells were grown in YPAD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 20 mg/ml adenine sulphate, 2% dextrose) at 30°C overnight and then the cultures were diluted to OD600 = 0.1. Most experiments were performed with exponential phase cells harvested between an OD600 of 0.3 and 0.6, unless otherwise indicated.

For conditional depletion of target proteins, cells were grown to log-phase (OD600 = 0.3–0.4) and anchor-away of FRB-tagged proteins was induced by treating cells with rapamycin (1 mg/ml of stock solution resuspended in 90% ethanol, 10% Tween-20) to 1 μg/ml final concentration for 20 min or 60 min before collection (35). Rapid depletion of auxin-induced degron (AID)-tagged proteins was induced by the addition of 3-indoloacetic acid (Auxin) at 500 mM final concentration (36). For heat stress experiments, cells were incubated in complete medium until log phase at 30°C, then the samples were briefly centrifuged, and pellets were resuspended in pre-warmed medium at the indicated temperatures and incubated for 5 min. Arrest of translation was induced by adding cycloheximide to a final concentration of 25 μg/ml. Ribosome biogenesis and secretion were inhibited by treatment of cells with diazaborine to a final concentration of 50 μg/ml or tunicamycin to a final concentration of 1 μg/mL, respectively.

Growth assays

Tenfold serial dilutions of log-phase growing cells (OD600 = 0.3) were spotted on plates containing complete medium (YPAD) or synthetic selective medium at indicated temperatures. Plates were imaged following 24 and 48 h incubations.

ChIP and ChIP-Seq

Yeast cultures of 50 mL in complete medium were collected at OD600 = 0.4–0.6 for each condition. The cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min and quenched by adding 125 mM glycine for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were then washed with ice-cold HBS (50 mM HEPES-Na pH:7.5, 140 mM NaCl) and resuspended in 0.6 ml of ChIP lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-Na pH:7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate) supplemented with 1 mM PMSF and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). The cells were broken using Zirconia/Silica beads (BioSpec) and lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. Following centrifugation, the pellets were resuspended in 300 μl ChIP lysis buffer containing 1 mM PMSF and sonicated for 15 min (30s ON–60s OFF) in a Bioruptor (Diagenode). The lysates were centrifuged at 7000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C, following which primary antibodies were added to the supernatant and incubated for 1 h at 4°C. ChIP was performed using the following antibodies: for RNAPII, Abcam ab5131; for Myc, mouse 9E10 monoclonal Ab culture supernatant produced in-house; for Hmo1, rabbit polyclonal Ab produced by Pocono Farms. Magnetic beads coupled to IgG against rabbit or mouse (Invitrogen, Dynabeads™ M-280 Sheep Anti-Rabbit or Anti-Mouse IgG) were washed three times with PBS (137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 10 mm Na2HPO4, 1.8 mm KH2PO4) containing 0.5% BSA and added to the lysates (30 μl of beads/300 μl of cell lysate). The samples were incubated for 2 h at 4°C. The beads were washed twice with AT1 buffer (50 mM HEPES-Na pH: 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.03% SDS), once with AT2 buffer (50 mM HEPES-Na pH: 7.5, 1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA), once with AT3 buffer (20 mM Tris–Cl pH: 7.5, 250 mM LiCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) and twice with TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA). The chromatin was eluted from the beads by resuspension in TE containing 1% SDS and incubation at 65°C for 10 min. The eluate was transferred to new Eppendorf tubes and incubated overnight at 65°C to reverse the crosslinks. The DNAs were purified using the MinElute PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen). DNA libraries were prepared using TruSeq ChIP Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina) according to manufacturer's specifications. The libraries were sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform at the Institute of Genetics and Genomics of Geneva (iGE3; http://www.ige3.unige.ch/genomics-platform.php) and the reads were mapped to the sacCer3 genome assembly using HTSStation60 (read densities were calculated using shift: 100, extension: 50 bp). All densities were normalized to 10M reads.

For RNAPII, the signal was quantified for each gene between the transcription start site (TSS) and transcription termination site (TTS). To quantify ChIP-seq signals for each promoter, a ratio between the total number of reads from each sample in a 400 bp region upstream the TSS (37) for each ORF and the total number of reads from the same region were obtained with mock IP of the control untagged strain. To compare depleted versus non-depleted cells, we divided the signal from the +auxin and/or +rapamycin samples by the signal from the—auxin and/or—rapamycin (vehicle) samples and log2 transformed this value. All data from publicly available databases were mapped using HTS Station (http://htsstation.epfl.ch; (38)). For ChIP-seq experiments, cross-linked chromatin obtained from fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe was used as a spike-in control (39). Values of ChIP-seq signal for each gene are reported in Supplementary Tables S1–S4 and S6.

ChEC-seq

ChEC-seq experiments were performed as described (40). ChEC-seq data from (23) were used to determine sites of Sfp1 and Ifh1 binding. A strain expressing ‘free’ MNase under control of the REB1 promoter was used as a control (40). Briefly, cells were washed twice with buffer A (15 mM Tris pH 7.5, 80 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.2 mM spermine, 0.5 mM spermidine, 1xRoche EDTA-free mini protease inhibitors, 1 mM PMSF) and resuspended in 200 μl of buffer A containing 0.1% digitonin. The cells were incubated at 30°C for 5 min. MNase activity was then induced by addition of CaCl2 to 5 mM and reactions were stopped at the indicated time points with EGTA at a final concentration of 50 mM. DNA was purified using MasterPure Yeast DNA purification Kit (Epicentre) according to the manufacturer's specifications. Large DNA fragments were removed by a 5-min incubation with 2.5× volume of AMPure beads (Agencourt) after which the supernatant was kept, and the MNase- digested DNA was precipitated using isopropanol.

Libraries were prepared using NEB Next kit (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Prior to PCR amplification of the libraries, small DNA fragments were selected by a 5-minute incubation in 0.9× volume of AMPure beads, after which the supernatant was kept and incubated with the same volume of beads as before for another 5 min. DNA was eluted with 0.1× TE after washing the beads with 80% ethanol and PCR was performed. Adaptor dimers were removed with a 5 min incubation using 0.8× volume of AMPure beads after which the supernatant was kept and incubated with 0.3× volume of the beads. The beads were then washed twice with 80% ethanol and DNA was eluted using 0.1× TE. The quality of the libraries was verified by running an aliquot on a 2% agarose gel. Libraries were sequenced using a HiSeq 2500 machine in single-end mode. Reads were extended by the read length. Reads were mapped to the genome (sacCer3 assembly) using HTSStation, and the position of the 5′-most base of each read was used as the position of the MNase cut site. All densities were normalized to 10M reads. For peak analysis, we used the signal obtained for Sfp1-MNase or Ifh1-MNase after 30 s or 2 min 30 s of CaCl2 treatment, respectively, normalized by dividing it by the signal obtained for free MNase after 20 min of treatment. Values of ChEC-seq signal at each promoter are reported in Supplementary Table S5.

Heat maps, plots and statistics

In all of the box plots, the box shows the 25th–75th percentile, whiskers show the 10th–90th percentile, and dots show the 5th and 95th percentiles. Statistical significance of difference between groups was evaluated using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test.

RESULTS

RPG promoter organization is heterogeneous but partitions into three distinct groups

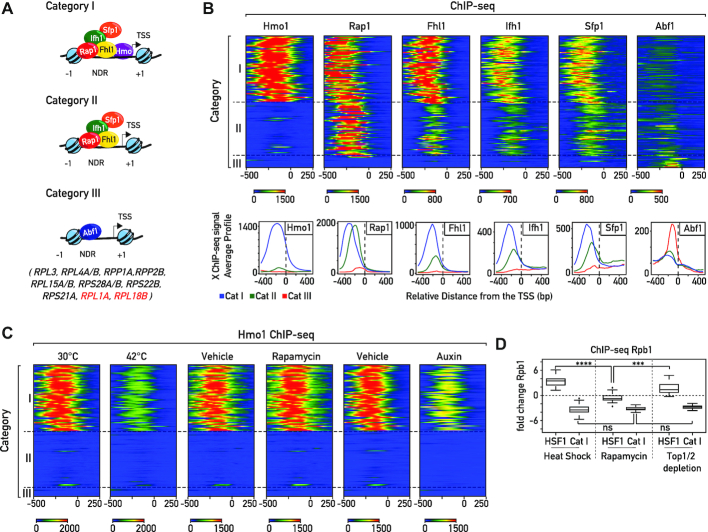

Previous studies (25–28) have partitioned RPGs into several groups according to the arrangement of bound TFs upstream of their promoters, as described above and summarized in graphic form in Figure 1A. The GRF Rap1 and the TFs Ifh1, Fhl1, and Sfp1 all bind to Cat I and Cat II promoters, whereas only the HMGB protein Hmo1 binds uniquely at Cat I promoters (Figure 1B). Although Hmo1 binding constitutes one of the most striking distinguishing features of RPG promoters, whether or not Hmo1 is involved in regulation of RPG expression upon stress is not clear. Hmo1 binding at RPG promoters was reported to rapidly decrease after exposure to high temperature (25,28) but its binding following TORC1 inhibition is controversial. It was initially reported that Hmo1 is removed from promoters and rDNA genes following rapamycin treatment (41). However, other groups found that Hmo1 remains bound to rDNA following inhibition of the growth regulator TORC1 by rapamycin (J. Griesenbeck, personal communication and (42)). Consistent with the latter view, we also found, by ChIP-seq that, Hmo1 binding is unaltered at RPGs following rapamycin treatment, in contrast to its rapid release from these promoters after heat shock (Figure 1C; (25,28)). Interestingly, under both conditions (heat shock and rapamycin treatment) RPG expression is strongly repressed (Figure 1D) showing that Hmo1 release is not necessary to repress RPGs transcription, at least upon rapamycin treatment. Furthermore, 20 minutes following inhibition of TORC1 by rapamycin treatment we find no evidence of Heat Shock Factor 1 (Hsf1) target gene activation, again specifically linking Hmo1 release to a proteotoxic stress response (Figure 1D). We recently showed that induced depletion of both topoisomerases 1 (Top1), or both Top1 and Top2, leads to the rapid induction of a proteotoxic stress pathway that we referred to as the Ribosome Assembly Stress Response (RASTR; (3)). During RASTR Hsf1 is activated and RPGs are downregulated, as observed during heat shock (Figure 1D). Interestingly, Hmo1 binding levels rapidly decrease at Cat I RPG promoters following depletion of both Top1 and Top2, despite the absence of thermal stress (Figure 1C). These data indicate that Hmo1 binding is affected by proteotoxic stress.

Figure 1.

Heterogeneous organization of RPG promoters. (A) Schematic representation of RPG categories according to their promoter nucleosome and transcription factor architecture. In each schema the left-most nucleosome represents the first stable -1 nucleosome, the right-most nucleosome represents the +1 nucleosome, black arrows represent the Transcription Start Site (TSS), and NDR corresponds to the nucleosome-depleted region (21,22,25–28). Genes included in Cat III (27) are reported. RPL1A and RPL18B are two peculiar cases in this group since Rap1 is detected at their promoters, though not Ifh1 and Fhl1. (B) Heat maps showing ChIP-seq signals for transcription factors Hmo1, Rap1, Fhl1, Ifh1, Sfp1 and Abf1 (from left panel to right panel) at RPG Categories I, II and III. Signals for a window of −500 to +250 bp relative to the TSS (bp) (0) are displayed (X-axis). Average Hmo1, Rap1, Fhl1, Ifh1, Sfp1, Abf1 binding profiles. Each profile is color-coded according to functional groups: Cat I (blue), Cat II (green) and Cat III (red). (C) Heat maps showing Hmo1 ChIP-seq signals at RPG promoters in cells following either 5 min of heat shock at 42°C, 20 min treatment with or without rapamycin, or rapid depletion of Top1/2 by 20 min of auxin treatment. Signals for a window of −500 to +250 bp relative to the TSS (bp) (0) are displayed (x-axis). (D) Box plots of log2 RNAPII (Rpb1) ChIP-seq change at Hsf1 target genes and Category I RPG promoters following 5 min of heat shock at 42°C (left panel), 20 min of rapamycin treatment (middle panel), or Top1/2 depletion (right panel). Asterisks show significant difference according to the Mann–Whitney test (*P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001, ns: not significant).

As pointed out above, the fact that Hmo1 is not released from RPG promoters during TORC1 inactivation, clearly demonstrates that release of Hmo1 from promoters during stress is not a prerequisite for RPG downregulation, at least upon TORC1 inactivation. In contrast, Ifh1, an essential activator dedicated almost exclusively to RPG transcription, is rapidly released from RPG promoters upon a wide range of stresses, including nutrient starvation, heat shock or TORC1 inactivation (13–16,18–22).

All promoters from Cat I and II have Rap1, Fhl1, Sfp1, Ifh1 at their promoters, but the thirteen Cat III promoters display a very different organization. This group of promoters is bound by Abf1 and depleted for Rap1, Fhl1, Ifh1, and Sfp1, apart from both RPL1A and RPL18B, whose promoters are bound by Rap1 but fail to recruit Fhl1, Ifh1 or Sfp1 at detectable levels (21,25–27). Cat III genes are expressed at similar levels to other RPGs (Supplemental Figure S1A) and code for both large and small subunit (60S and 40S) ribosomal proteins (Figure 1A). The absence at Cat III genes of common TFs shared with other RPGs raises the question of how they are co-regulated with the Cat I and Cat II genes. A previous study reported the presence of an Fhl1 binding motif in close proximity to Abf1 binding sites at several Cat III genes (31). Nevertheless, the in vivo functionality of these Fhl1 binding sites remains controversial. Although Fhl1’s ability to bind these sequences has been confirmed by in vitro experiments, ChIP experiments performed by us and others revealed only very weak or no binding at Cat III promoters (Figure 1B; (14,27,28,31)).

Coregulation of the three groups of RPGs is adjusted according to growth conditions

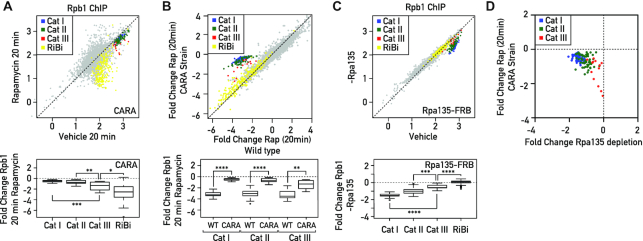

To gain insight into the extent to which expression of the three categories of RPGs is coordinated, we first measured their transcription following TORC1 inactivation by rapamycin, which mimics nutrient starvation (e.g. carbon, nitrogen, phosphate or amino acid limitation). Importantly, inactivation of TORC1 also occurs in other types of stress, such as osmotic stress, redox stress, or caffeine treatment. We used RNA Polymerase II (RNAPII) ChIP-seq as a proxy for transcription since steady-state mRNA levels can mask transcription effects that are buffered by compensatory mRNA stability changes (43). As expected, inhibition of growth by rapamycin triggers global changes in the transcription program (Figure 2A), and more specifically leads to rapid downregulation of the three groups of RPGs, at both 5 and 20 min post treatment, without significant differences between Cat I, II and III genes (Figure 2A, left and middle panels). Moreover, RiBi genes, known to be regulated by Sfp1 according to growth conditions (24,44), are also downregulated to a similar extent, though in a more heterogeneous fashion (Figure 2A). These findings reveal that, despite heterogeneous promoter structures, cells have developed mechanisms of comparable efficiency to rapidly coregulate RNAPII recruitment to all RPGs upon TORC1 inactivation. Nevertheless, we noted that following a 1 h rapamycin treatment Cat III genes (largely bound by Abf1) are less downregulated and display a pattern more similar to RiBi genes than to the other RPGs (Figure 2A, right panel). This latter result points to the existence of distinct mechanisms to regulate the three groups of RPGs, allowing the cell to differentially modulate expression of RPGs under certain conditions.

Figure 2.

The three distinct categories of RPGs are co-regulated according to growth conditions. (A) Scatter plots (top panels) comparing RNAPII binding (as measured by Rpb1 ChIP-seq) in WT cells treated with rapamycin (Y-axis) or vehicle (X-axis) for 5 min (left panel), 20 min (middle panel) and 60 min (right panel). Each dot represents a gene (5041 in total) and genes are color-coded according to functional groups as Cat I (blue), Cat II (green) and Cat III (red) RPGs; RiBi genes (yellow); all other genes (grey). For RNAPII, the average signal was quantified from the TSS to the transcription termination site (TTS). The scale for both the X-axis and the Y-axis is log10. Bottom panels display the corresponding box plots for the four indicated gene categories. (B) Box plots showing RNAPII (Rpb1) ChIP-seq change for RPGs and RiBi genes in different growth conditions; upper panel shows the result of treatment with tunicamycin (30 min, left panel), diamide (20 min, middle panel) and glucose pulse (5 min, right panel); bottom panel shows the result of treatment with heat shock (5 min, left panel), diazaborine (20 min, middle panel) and cycloheximide (CHX, 20 min, right panel). Asterisks show significant difference according to the Mann–Whitney test (*P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001, ns: not significant).

To pursue this observation further we examined other conditions in which RPG transcription is known to be strongly affected, including glucose addition to cells growing in a poor carbon source (glycerol), heat shock, and oxidative stress (diamide treatment). We also tested the effects of arresting the secretion pathway, blocking translation elongation and inhibiting ribosome biogenesis, by treating cells with tunicamycin, cycloheximide (CHX), and diazaborine, respectively. Interestingly, downregulation following tunicamycin or diamide treatments and upregulation after a 5 min glucose pulse are very similar for the three RPG categories, whereas heat shock, arrest of ribosome biogenesis by diazaborine or CHX treatment all trigger a more heterogeneous response, with Cat III genes responding more weakly to compared to Cat I and II genes (Figure 2B). Of interest, heat shock and diazaborine treatment were recently reported to trigger significant changes in protein homeostasis leading to accumulation of unassembled (‘orphan’) RPs, sequestration of Ifh1 in aggregates, and repression of RPGs (3,7). In contrast, CHX treatment prevents Ifh1 aggregation and upregulates RPG transcription, probably by preventing neo-synthesis of the orphan RPs that cause Ifh1 aggregation (3). These results demonstrate that strict RPG co-regulation is operative in some but not all conditions, suggesting that the different categories of RPGs are regulated through at least partly distinct mechanisms.

Co-regulation of RPGs through Ifh1-dependent and Ifh1-independent mechanisms

It was previously reported that the expression of RPGs is aligned to RNAPI activity (13,45). To test whether all three categories of RPGs have this ability for co-regulation with RNAPI, we measured their expression following TORC1 inactivation by rapamycin treatment in cells where RNAPI is rendered constitutively active by expression of its Rrn3 and Rpa43 subunits as a fusion protein (CARA strain: Constitutive Association of Rrn3 and Rpa43; (45)). As expected, transcriptional regulation of RPGs upon stress was specifically affected in the CARA strain, where RNAPI inhibition is blocked, whereas expression of other TORC1-sensitive genes remained unchanged (Figure 3A, compare with Figure 2A, middle panels). Contrary to what we observed previously in a wild-type strain, the transcriptional response of the three RPG categories was no longer homogeneous after 20 minutes of rapamycin treatment in the CARA strain. Cat I and II genes, which have Ifh1 at their promoters, were very weakly downregulated, whereas Cat III genes, whose promoters are devoid of Ifh1, were repressed more strongly (Figure 3A-B). This observation is consistent with our previous finding, in which we uncovered a crosstalk between RNAPI and RPG expression that is abrogated in the CARA strain. This mechanism is dependent upon Ifh1 and its interaction with the CK2–Utp22–Rrp7–Ifh1 (CURI) complex, which is itself responsive to RNAPI activity (13). However, we noted that repression of Cat III genes upon TORC1 inactivation in the CARA strain was still not complete (Figure 3B), suggesting that Ifh1 might play a partial role in the regulation of these genes in coordination with RNAPI activity.

Figure 3.

Coordinated downregulation of RPGs expression is carried out by Ifh1-dependent or Ifh1-independent processes. (A) RNAPII ChIP-seq in CARA strain cells (Y-axis) versus WT cells (X-axis) following to treatment with Rapamycin for 20 min. Bottom panels display the corresponding box plots for the four indicated gene categories. (B) Fold change of RNAPII binding following 20 minutes of rapamycin treatment in CARA strain cells (Y-axis) versus fold change of RNAPII binding following 20 minutes of rapamycin treatment in WT cells (X-axis). Bottom panels display the corresponding box plots for the three indicated gene categories. (C) RNAPII ChIP-seq in Rpa135 nuclear-depleted cells (−Rpa135; Y-axis) versus non-depleted cells (Vehicle; X-axis). Bottom panels display the corresponding box plots for the four indicated gene categories. (D) Scatter plots comparing RNAPII (Rpb1) binding fold change at RPGs categories in CARA strain cells treated with Rapamycin for 20 min (Y-axis) versus Rpa135 nuclear-depleted cells. Genes are color-coded according to functional groups: Cat I (blue), Cat II (green) and Cat III (red) RPGs.

To further test the ability of Cat III gene expression to be influenced by RNAPI activity, we chose to decrease rRNA production by nuclear depletion of one subunit of RNAPI (Rpa135), using the anchor-away system (35). Remarkably, 60 min of Rpa135 nuclear depletion led to specific downregulation of RPG expression whilst other groups of genes, such as RiBi genes (used here as a proxy of TORC1 activity), were unaffected (Figure 3C). Interestingly, the Cat III RPGs, which were strongly affected by TORC1 inhibition in an RNAPI-independent process in the CARA strain, were the least affected by Rpa135 nuclear depletion (Figure 3D). These data confirm that all RPGs, including Cat III genes, are sensitive to a decrease of RNAPI activity, but to different extents. These results also confirm that several mechanisms co-regulate RPGs following TORC1 inactivation: one is Ifh1- and RNAPI-dependent and only partially effective on Cat III genes, while acting strongly on Cat I and II genes. Another mechanism is Ifh1- and RNAPI-independent and strongly affects Cat III genes, but only weakly influences Cat I and II genes. The complementary action of these two mechanisms appears to be required to fine-tune co-regulation of all RPGs following TORC1 inactivation.

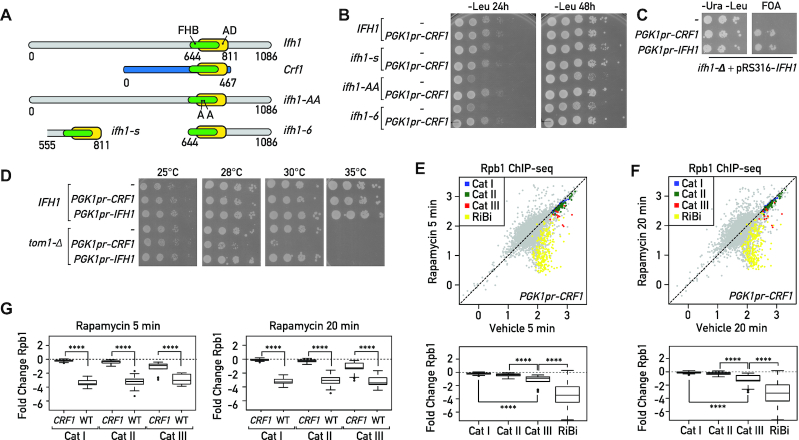

Crf1 is a non-regulatable activator of RPGs

It was initially suggested that Crf1, an Ifh1 paralog, acts as a negative regulator of RPGs following TORC1 inactivation by competing with Ifh1 for binding to RPG promoters (18). Indeed, Crf1 has a well conserved forkhead-associated binding (FHB) domain (Figure 4A) through which it binds to the forkhead-associated (FHA) domain of Fhl1 (18), and deletion of CRF1 in the TB50 strain background reduces RPG downregulation in response to rapamycin treatment (18,32). Surprisingly, though, deletion of CRF1 does not prevent the downregulation of RPGs following rapamycin treatment in the W303 strain background (32), where Crf1 expression may be weak or non-existent, as judged by western blot or RNAPII binding at its ORF (data not shown). Consistent with the notion of regulatory system divergence between TB50 and the more widely used W303 background, and despite the fact that RNAPII binding at RPGs is highly similar in these two backgrounds (Supplemental Figure S2A), Cat I and II are downregulated less efficiently in TB50 following rapamycin treatment whereas Cat III and RiBi genes are similarly affected in the two strains (Supplemental Figure S2B).

Figure 4.

Crf1 is a non-regulatable activator of RPGs. (A) Schematic representation of conserved domains in full length Ifh1 and Crf1 proteins, and a series of Ifh1 point mutations S680A/S681A (ifh1-AA) or truncated alleles: an Ifh1 mutant that removes all sequences upstream of the FHB and linked activation domain (ifh1–6); an extremely short version of Ifh1 (ifh1-s) containing essentially the FHB and downstream activation domain (from top to bottom). FHB: Fork Head Binding domain, AD: Activation domain. (B) 10-fold serial dilution of wild-type (IFH1) or hypomorphic alleles of Ifh1 (ifh1-s, ifh1-AA, Ifh1–6), transformed with a plasmid bearing the CRF1 coding region under the control of the PGK promoter (pPGK1pr-CRF1) or with the empty pPGK1pr vector (−). Cells were spotted onto the indicated selective media and the plates were incubated at 30°C for 24 or 48 h. (C) A null allele (ifh1-Δ) present at the endogenous genomic locus of the haploid tester strain is complemented by the wild-type gene borne on a URA3-containing plasmid (pRS316-IFH1). Complementation is tested by examining whether plasmids expressing Crf1 (PGK1pr-CRF1) or Ifh1 (PGK1pr-CRF1) from a strong promoter bypass the lethal phenotype, as monitored by growth on FOA. The empty pPGK1pr vector (−) is used as negative control. Plates without FOA (-Ura, -Leu) are used as control to confirm that the same number of cells were spotted. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 48 h. (D) 10-fold serial dilution of wild-type (IFH1) or TOM1 deleted cells (tom1-Δ), transformed with a plasmid bearing CRF1 or IFH1 coding regions under the control of PGK promoter (pPGK1pr-CRF1 or pPGK1pr-IFH1, respectively) or with the empty pPGK1pr vector (−). Cells were spotted onto the indicated selective media and the plates were incubated at the indicated temperatures for 48 h. (E, F) Scatter plots comparing RNAPII (Rpb1) ChIP-seq in Crf1 expressing cells after 5 min (Y-axis, E) or 20 min (Y-axis, F) Rapamycin treatment to non-treated cells (Vehicle; X-axis). Bottom panels display the corresponding box plots for the four indicated gene categories. Gene groups are color-coded as indicated above. (G) Box plots comparing RNAPII (Rpb1) binding fold change at RPGs categories in CRF1 expressing and WT cells treated with rapamycin for 5 min (left panel) or 20 min (right panel). Asterisks show significant difference according to Mann-Whitney test.

In order to reveal additional structural properties of different RPG categories, we tested the idea that forced Crf1 expression might inhibit growth in the W303 background through competition with Ifh1 for RPG promoter binding, by introducing a plasmid bearing the CRF1 coding region under control of the strong and constitutive PGK1 promoter. Surprisingly, overexpression of Crf1 had no effect on growth under optimal conditions, but instead suppressed the growth defect of different hypomorphic IFH1 alleles (ifh1-AA, ifh1-s, ifh1-6; Figure 4B) and, remarkably, rescued the lethality of IFH1 deletion (Figure 4C).

Although Crf1 contains an FHB domain highly similar to that of Ifh1, it completely lacks the C- and N-terminal regions of Ifh1 that are implicated in the removal of Ifh1 from RPG promoters upon stress (Figure 4A; (3,13)). The absence of these C- and N-terminal extensions may help Crf1 to compete efficiently with Ifh1 under stress conditions. Interestingly, elevated CRF1 protein level becomes highly toxic at 30°C in a strain deleted for TOM1, which encodes a ubiquitin ligase required for degradation of ribosomal proteins produced in excess, suggesting that excess Crf1 dysregulates RP production (Figure 4D). Consistent with this idea, increased CRF1 expression prevents the repression of Cat I and II genes at both 5 and 20 min following rapamycin treatment (Figure 4E, F; compare with Figure 2A, left and middle panels). For the case of Cat III genes, increased CRF1 expression has a smaller but still significant effect (Figure 4E–G) in comparison to other genes downregulated following rapamycin treatment, such as RiBi genes, which are completely unaffected by CRF1 expression. This latter finding bolsters the idea that Fhl1 binding sites in proximity to Abf1 (31) can act, through the FHA–FHB interaction, to recruit either Crf1 or Ifh1. Nevertheless, as shown above, a major part of the transcriptional downregulation of Cat III genes is carried out by an Ifh1-independent process.

Both Sfp1 and Ifh1 are recruited to Cat III promoters

We next examined the DNA sequences at Cat III promoters in search of other possible regulatory features of these genes. This analysis revealed that RPG promoter categories are distinguished not just by transcription factor binding heterogeneity, but also by differences in nucleosome depleted region (NDR) size and G/C content (Figure 5A). These features are distinctive between the three categories of RPGs: Cat I promoters have a high G/C content and the largest NDRs, whilst Cat III promoters have the smallest NDRs and the lowest G/C content (Figure 5B). The G/C content of Cat I promoters may be important to maintain a large NDR, by promoting RSC (Remodels the Structure of Chromatin) and Hmo1 binding (27,46–48). On the other hand, it could also introduce a bias in ChIP assays, due to the strong propensity for formaldehyde crosslinking at G/C versus A/T base pairs (49), which might lead to low detection of proteins such as Abf1, which is enriched at Cat III promoters (31). We also noted that Cat III promoters are enriched in a motif (gAAAATTTTc) bound by Sfp1, both in vitro and in vivo (Figure 5C; (23,50)), which is itself largely depleted for G/C base pairs. We recently reported (23) that Sfp1 binding is undetectable by ChIP at RiBi promoters enriched for the Sfp1 binding motif but can be revealed by an alternative assay that does not require formaldehyde cross linking, Chromatin Endogenous Cleavage (ChEC; (51)). We thus used our published ChEC-seq data (23) to compare binding of Sfp1 at the different groups of RPG promoters. Strikingly, Sfp1 ChEC-seq signals were highest at Cat III promoters, comparable in strength to those observed at RiBi genes, and more globally displayed an opposite pattern at the three RPG promoter categories compared to Sfp1 signal strengths observed by ChIP-seq (Figure 5D, E). This finding suggests that Sfp1 could be the ‘missing’ regulator of Abf1-dependent genes following TORC1 inactivation (see also below), and that structural properties of Cat III promoters probably limit its ability to be detected by ChIP at these sites. Interestingly, Ifh1 ChEC-seq also revealed significant binding at Cat III promoters, where it is essentially undetectable by ChIP, in comparison with RiBi gene promoters or a group of 200 RNAPII promoters chosen at random (Figure 5D, E). However, contrary to Sfp1 ChEC-seq, Ifh1 ChEC-seq yielded a stronger signal on Cat I and Cat II compared to Cat III promoters. This Ifh1 binding pattern revealed by ChEC-seq is fully consistent with results presented above suggesting that Ifh1 has a minor but significant role in the regulation of Cat III genes in comparison to its major role at Cat I and II genes.

Figure 5.

Sfp1 and Ifh1 are directly recruited at Cat III promoters. (A) Heat maps showing MNase digestion patterns (left panel) and G/C content (right panel) at RPGs promoters. Signals for a window of −500 to +250 bp relative to the +1 nucleosome (0) are displayed (X-axis). (B) Average plots of MNase digestion patterns (upper panel) and G/C content (lower panel) at three categories of RPGs. Signals for a window of −500 to +250 bp relative to the TSS (bp) (0) are displayed (X-axis). (C) Heat maps showing Sfp1-binding motif and Sfp1 ChEC-seq signal for 150 s of Ca+2 treatment, or Ifh1 ChEC-seq signal after 150 sec of Ca+2 treatment at the indicated RPGs promoters. Control for ChEC-seq signal (free-MNase, 20 min following Ca+2 addition) is used as background control. Average plots of Ifh1, Sfp1, Free-MNase ChEC-seq signal at three categories of RPGs is also shown (lower panel). Signals for a window of −500 to +250 bp relative to the TSS (bp) (0) are displayed (X-axis). (D) Genome browser tracks comparing Sfp1-MNase, Ifh1-MNase and free MNase ChEC-seq signals (blue background) to Sfp1-TAP, Ifh1-Myc and untagged ChIP-seq read counts (yellow background) at RPS28A (Cat III) and RPS30B (Cat II) RPGs. The position of indicated RPGs promoters are shown above of the tracks. (E) Box plots of log2 ChEC-seq or ChIP-seq signal related to ChEC or ChIP control (free MNase or untagged strains) at promoters of different groups of genes (Cat I, II, III, ribosome biogenesis [RiBi] genes, others [200 randomly chosen protein-coding genes]) for Sfp1-MNase and Ifh1-MNase (ChEC-seq, blue background) or Sfp1-TAP and Ifh1-Myc (ChIP-seq, yellow background), respectively.

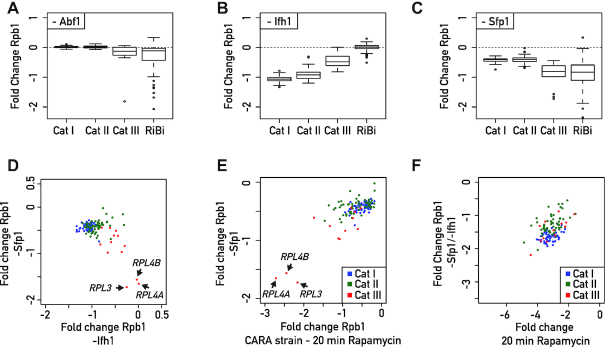

Coordinated downregulation of RPGs by complementary regulation of both Sfp1 and Ifh1

Taken together, the results described above allow us to propose a new organizational principle of TFs at RPG promoters in which Ifh1 and Sfp1 can bind to and influence expression of all RPGs, including the small group of Cat III genes bound by the GRF Abf1, instead of Rap1. In order to challenge this model by a functional assay, we measured RNAPII recruitment in the absence of factors detected at the Cat III promoters: Abf1, Sfp1 and Ifh1. Abf1 depletion triggered a very slight decrease of RNAPII recruitment at Cat III genes with only RPL4A being strongly affected (Figure 6A). In contrast, numerous non-RP Abf1 target genes were strongly affected by Abf1 depletion across the genome (Supplemental Figure S3A). Interestingly, these other Abf1 target genes are unaffected by TORC1 inactivation, suggesting that the transcriptional effect observed following TORC1 inactivation at Category III RPGs is independent of a decrease in Abf1 binding at these promoters. Next, we assessed the consequence of depletion of the stress sensitive factors Ifh1 and Sfp1. Consistent with our previous results (23), Ifh1 depletion triggered strong downregulation of Rap1-dependent genes and a significant though smaller decrease in transcription of Cat III genes (Figure 6B). Importantly, Sfp1 depletion caused an opposite transcriptional response to that of Ifh1 depletion, with Cat III RPGs being the most downregulated, and Cat I and II genes the least affected (Figure 6C). Remarkably, these results are fully consistent with ChEC-seq data indicating that Sfp1 binds more strongly to Cat III than Cat I or Cat II gene promoters, with the opposite being true for Ifh1 (Figure 5E). It is also interesting to note that the three RPGs least affected by Ifh1 depletion (RPL3, RPL4A, RPL4B) were also the most downregulated ones following Sfp1 depletion (Figure 6D), highlighting the complementary action of these two stress-sensitive TFs. Moreover, changes of RNAPII occupancy upon Sfp1 depletion are highly similar to those observed following TORC1 inhibition in the CARA strain, where promoter release of Ifh1 is specifically blocked (Figure 6E). This latter result strongly supports the idea that Sfp1 is the missing factor required for coordinated repression of RPGs together with Ifh1. According to our model, then, Ifh1 is the main regulator of Cat I and II genes but can also influence Cat III genes, whereas Sfp1 modestly affects Cat I and II genes but is the key regulator at Cat III genes. The combined action of these two stress-sensitive TFs is required to coordinate RPGs promoter activity upon stress. Consistent with this claim, only double depletion of Ifh1 and Sfp1 leads to a level of RPG downregulation that correlates well with what is observed following TORC1 inactivation (Figure 6F).

Figure 6.

Coordinated regulation of RPGs expression is accomplished by the complementary actions of Sfp1 and Ifh1. (A–C) Box plots showing RNAPII binding change measured by Rpb1 ChIP-seq in Abf1 (A), Ifh1 (B) or Sfp1 (C) nuclear-depleted cells (calculated as log2 ratio of nuclear-depleted versus non-depleted cells) for RPGs and RiBi genes. (D–F) Scatter plots comparing RNAPII (Rpb1) binding fold change for Sfp1 nuclear-depleted cells (-Sfp1; Y-axis) versus Ifh1 nuclear-depleted cells (-Ifh1; X-axis) (D); in Sfp1 nuclear-depleted cells (-Sfp1; Y-axis) versus CARA strain cells treated with Rapamycin for 20 min (CARA; x-axis) (E); in double depletion of Ifh1 and Sfp1 (-Sfp1-Ifh1; Y-axis) versus WT cells treated with Rapamycin for 20 min (X-axis) (F). Each dot represents a gene color-coded according to functional group as above (blue: Cat I, green: Cat II, red: Cat III).

DISCUSSION

Although DNA sequences features and TF binding at RPG promoters have been extensively studied using genome-wide methods in yeast (11,26–28), significant gaps persist in our understanding of how RPGs with heterogeneous promoter organization are coordinately regulated in response to growth and stress signals. In fact, RPG promoters that are not bound by the GRF Rap1 and which lack a duplicate copy under the control of Rap1-dependent mechanisms, such as RPL3 and RPL4A/B, were thought not to be coordinately expressed with other RPGs (28). Our results demonstrate that all RPGs are regulated by the complementary action of the stress-sensitive TFs Ifh1 and Sfp1, which clarifies this apparent paradox. The results described here provide a more complete picture of the involvement of specific TFs in regulating RPG expression during stress. Our principal findings regarding the architecture of RPG promoters and their regulatory factors are summarized in a schematic form in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of proposed model of heterogeneous organization of RPGs promoters and their regulatory factors. All RPGs are regulated by two distinct, but complementary mechanisms driven by Sfp1 and Ifh1 that are required to coordinate RPG transcription upon stress. Category I and Category II RPG promoters contain the general regulatory factor Rap1 and the transcription factors Ifh1, Fhl1, Sfp1 at their promoters. Category I genes are in addition bound by the HMGB protein Hmo1. Category III promoters are bound by Abf1 (except for RPL1A and RPL18B) and are also regulated by Sfp1 and Ifh1. Ifh1 and Sfp1 release under various stress conditions downregulates RPG transcription. Ifh1 is specifically sensitive to proteotoxic stress, RNAPI activity, and TORC1 inactivation. Category III promoters are bound by the general regulatory factor Abf1 and at these RPGs Sfp1 is the key regulator. Ifh1 is the main regulator of Cat I and II but can also influence Cat III, whereas Sfp1 modestly affects Cat I and II but strongly regulates Cat III genes. The coordinated action of these two stress sensitive transcription factors are required to coordinate RPG promoter activity upon stress.

In this study, we revealed unexpected features of Hmo1 by showing its dynamic binding sensitivity upon proteotoxic stress. Interestingly, it was reported that Hmo1 transiently partitions into an aggregated protein fraction after heat shock at 42°C, suggesting that the decrease in Hmo1 binding at promoters could be linked to its sequestration in an insoluble or phase-separated state (25,28,52). Further investigation will be required to determine whether the ability of Hmo1 to transiently aggregate could be linked to some regulatory function at RPG promoters or at rDNA genes, where Hmo1 is also enriched. Nevertheless, it is becoming increasingly apparent that ribosome biogenesis is directly linked to regulation of protein homeostasis (3,5–7). We recently demonstrated that ribosome assembly impairment in yeast triggers a rapid stress response in which RPGs are strongly downregulated and Hsf1 target genes are upregulated (3). Moreover, we showed that this so-called Ribosome Assembly Stress Response (RASTR) is driven by orphan RP aggregation, triggering sequestration of Ifh1 in an insoluble fraction, whereas Sfp1’s activity remains unaffected during RASTR. The fact that Sfp1 activity is not affected by RASTR raises the issue of over-accumulation and aggregation of RPs encoded by genes controlled by Sfp1, such as RPL4A/B and RPL3, which are weakly affected by Ifh1 depletion or during RASTR. Interestingly, both Rpl4 and Rpl3 belong to a restrictive group of RPs with a dedicated chaperone (53), suggesting that the latter can compensate for the absence of their downregulation upon stress. On the other hand, protein quality control (PQC) mechanisms may contribute to prevent aggregation of other unassembled RPs. Accordingly, in strains where the excess ribosomal protein quality control (ERISQ) pathway is ablated (e.g. tom1Δ cells), we showed that Crf1 expression becomes toxic, indicating that regulation of RPG transcription is important to maintain protein homeostasis.

Many years ago, Laferté et al. (45) described a yeast strain expressing a version of RNAPI that remains constitutively active under stress, which led to the notion of the central role of this enzyme in coordinating stoichiometric levels of ribosome components (54). Similarly, we constructed here a strain (overexpressing CRF1) that prevents the proper regulation of RPG expression, which normally accounts for about 50% of RNAPII initiation events in growing cells (2). This strain represents a promising tool to understand the importance of modulation of RPG expression during the cell cycle, stress or meiosis. For example, several studies have shown that splicing machinery is present in limiting amounts, suggesting that the splicing process may be modulated by changing the amount of pre-mRNA substrate-containing introns (55). Given that RPGs produce the major fraction of intron-containing pre-mRNA and that endoplasmic reticulum stress or meiosis both involve downregulation of RPGs and splicing of stress- or meiosis-specific genes, respectively (56,57), it could be interesting to challenge the importance of RPG downregulation in these processes by using this CRF1-overexpressing strain. It could also be interesting to determine to what extent the maintenance of a high pool of RPG mRNAs upon stress could prevent proper translation of mRNAs derived from stress genes that need to be rapidly transcribed and translated under these conditions.

It might seem at first that a simpler system in which all RPGs would be controlled by a common mechanism would make more evolutionary sense. However, after the whole genome duplication preceding the emergence of S. cerevisiae, most RPG paralogues were actually conserved, despite the fact that nearly 90% of all duplicated genes were eliminated. This could suggest that a higher level of complexity in RPG regulation provides a selective advantage (58,59). It is tempting to hypothesize that the differential RPG regulation described in this study will also increase the ability of cells to respond to varying growth conditions. Indeed, differential RPG promoter regulation could provide plasticity to RP paralogue production, which might in turn favor functional differences in specialized ribosomes (60–62). It was also proposed that Abf1 binding at RPG promoters may help in rapid resumption of transcription after stress (31). Such differential RPG regulation could contribute to regulate specifically the expression of pleiotropic RPGs that have other roles in addition to their original ribosomal functions (63). In this sense, it is interesting to note that genes from Cat III, which are highly sensitive to Sfp1, are enriched in those encoding extra-ribosomal functions (28). The combination of intrinsic DNA features encoded in the promoter and the ability to modulate the recruitment of a different set of TFs described in this study are probably the major determinants of RPG promoter activity in budding yeast. We imagine that pre-mRNA splicing, mRNA decay and protein turnover provide additional layers of complexity to achieve a balanced production of ribosome components that allows for efficient ribosome assembly while avoiding the proteotoxicity of unassembled RPs.

In metazoan cells, transcription of rDNA genes is relatively well studied, and its general properties are highly conserved (64). However, the general features of metazoan RPG expression are much less well understood compared to yeast. Given that the defect of expression of some RPs leads to a heterogeneous class of diseases known as ribosomopathies, and reports that RPGs exhibit tissue- or disease-specific expression patterns in mammalian cells (65), future studies should seek to identify mechanisms orchestrating RPG expression in metazoan cells and organisms.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All deep sequencing data sets have been submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under accession code GSE155235.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank to all members of the Shore lab for comments and discussions throughout the course of this work; Mylène Docquier and the Genomics Platform of iGE3 at the University of Geneva (https://ige3.genomics.unige.ch/) for expert high-throughput sequencing services; Prof. Helmut Bergler (Karl-Franzens-Universität, Graz, Austria) for his generous gift of diazaborine; Nicolas Roggli for expert assistance with data presentation and artwork.

Contributor Information

Sevil Zencir, Department of Molecular Biology and Institute of Genetics and Genomics of Geneva (iGE3), University of Geneva, 30 quai Ernest-Ansermet, 1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland.

Daniel Dilg, Department of Molecular Biology and Institute of Genetics and Genomics of Geneva (iGE3), University of Geneva, 30 quai Ernest-Ansermet, 1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland.

Maria Paula Rueda, Department of Molecular Biology and Institute of Genetics and Genomics of Geneva (iGE3), University of Geneva, 30 quai Ernest-Ansermet, 1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland.

David Shore, Department of Molecular Biology and Institute of Genetics and Genomics of Geneva (iGE3), University of Geneva, 30 quai Ernest-Ansermet, 1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland.

Benjamin Albert, Department of Molecular Biology and Institute of Genetics and Genomics of Geneva (iGE3), University of Geneva, 30 quai Ernest-Ansermet, 1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

B.A. acknowledges support from a long-term EMBO postdoctoral fellowship in the early phases of this work; D.S. acknowledges funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation [31003A_170153]; Republic and Canton of Geneva. Funding for open access charge: Swiss National Science Foundation.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lempiainen H., Shore D.. Growth control and ribosome biogenesis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009; 21:855–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Warner J.R. The economics of ribosome biosynthesis in yeast. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1999; 24:437–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Albert B., Kos-Braun I.C., Henras A.K., Dez C., Rueda M.P., Zhang X., Gadal O., Kos M., Shore D.. A ribosome assembly stress response regulates transcription to maintain proteome homeostasis. Elife. 2019; 8:e45002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lam Y.W., Lamond A.I., Mann M., Andersen J.S.. Analysis of nucleolar protein dynamics reveals the nuclear degradation of ribosomal proteins. Curr. Biol. 2007; 17:749–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sung M.K., Porras-Yakushi T.R., Reitsma J.M., Huber F.M., Sweredoski M.J., Hoelz A., Hess S., Deshaies R.J.. A conserved quality-control pathway that mediates degradation of unassembled ribosomal proteins. Elife. 2016; 5:e19105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sung M.K., Reitsma J.M., Sweredoski M.J., Hess S., Deshaies R.J.. Ribosomal proteins produced in excess are degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2016; 27:2642–2652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tye B.W., Commins N., Ryazanova L.V., Wuhr M., Springer M., Pincus D., Churchman L.S.. Proteotoxicity from aberrant ribosome biogenesis compromises cell fitness. Elife. 2019; 8:e43002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Narla A., Ebert B.L.. Ribosomopathies: human disorders of ribosome dysfunction. Blood. 2010; 115:3196–3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Deutschbauer A.M., Jaramillo D.F., Proctor M., Kumm J., Hillenmeyer M.E., Davis R.W., Nislow C., Giaever G.. Mechanisms of haploinsufficiency revealed by genome-wide profiling in yeast. Genetics. 2005; 169:1915–1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Parenteau J., Durand M., Morin G., Gagnon J., Lucier J.F., Wellinger R.J., Chabot B., Elela S.A.. Introns within ribosomal protein genes regulate the production and function of yeast ribosomes. Cell. 2011; 147:320–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zeevi D., Sharon E., Lotan-Pompan M., Lubling Y., Shipony Z., Raveh-Sadka T., Keren L., Levo M., Weinberger A., Segal E.. Compensation for differences in gene copy number among yeast ribosomal proteins is encoded within their promoters. Genome Res. 2011; 21:2114–2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Petibon C., Parenteau J., Catala M., Elela S.A.. Introns regulate the production of ribosomal proteins by modulating splicing of duplicated ribosomal protein genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:3878–3891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Albert B., Knight B., Merwin J., Martin V., Ottoz D., Gloor Y., Bruzzone M.J., Rudner A., Shore D.. A molecular titration system coordinates ribosomal protein gene transcription with ribosomal RNA synthesis. Mol. Cell. 2016; 64:720–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cai L., McCormick M.A., Kennedy B.K., Tu B.P.. Integration of multiple nutrient cues and regulation of lifespan by ribosomal transcription factor Ifh1. Cell Rep. 2013; 4:1063–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Downey M., Knight B., Vashisht A.A., Seller C.A., Wohlschlegel J.A., Shore D., Toczyski D.P.. Gcn5 and sirtuins regulate acetylation of the ribosomal protein transcription factor ifh1. Curr. Biol. 2013; 23:1638–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jorgensen P., Rupes I., Sharom J.R., Schneper L., Broach J.R., Tyers M.. A dynamic transcriptional network communicates growth potential to ribosome synthesis and critical cell size. Genes Dev. 2004; 18:2491–2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marion R.M., Regev A., Segal E., Barash Y., Koller D., Friedman N., O'Shea E.K.. Sfp1 is a stress- and nutrient-sensitive regulator of ribosomal protein gene expression. PNAS. 2004; 101:14315–14322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Martin D.E., Soulard A., Hall M.N.. TOR regulates ribosomal protein gene expression via PKA and the forkhead transcription factor FHL1. Cell. 2004; 119:969–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rudra D., Mallick J., Zhao Y., Warner J.R.. Potential interface between ribosomal protein production and pre-rRNA processing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007; 27:4815–4824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rudra D., Zhao Y., Warner J.R.. Central role of Ifh1p-Fhl1p interaction in the synthesis of yeast ribosomal proteins. EMBO J. 2005; 24:533–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schawalder S.B., Kabani M., Howald I., Choudhury U., Werner M., Shore D.. Growth-regulated recruitment of the essential yeast ribosomal protein gene activator Ifh1. Nature. 2004; 432:1058–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wade J.T., Hall D.B., Struhl K.. The transcription factor Ifh1 is a key regulator of yeast ribosomal protein genes. Nature. 2004; 432:1054–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Albert B., Tomassetti S., Gloor Y., Dilg D., Mattarocci S., Kubik S., Hafner L., Shore D.. Sfp1 regulates transcriptional networks driving cell growth and division through multiple promoter-binding modes. Genes Dev. 2019; 33:288–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cipollina C., van den Brink J., Daran-Lapujade P., Pronk J.T., Vai M., de Winde J.H.. Revisiting the role of yeast Sfp1 in ribosome biogenesis and cell size control: a chemostat study. Microbiology. 2008; 154:337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hall D.B., Wade J.T., Struhl K.. An HMG protein, Hmo1, associates with promoters of many ribosomal protein genes and throughout the rRNA gene locus in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006; 26:3672–3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kasahara K., Ohtsuki K., Ki S., Aoyama K., Takahashi H., Kobayashi T., Shirahige K., Kokubo T.. Assembly of regulatory factors on rRNA and ribosomal protein genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007; 27:6686–6705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Knight B., Kubik S., Ghosh B., Bruzzone M.J., Geertz M., Martin V., Denervaud N., Jacquet P., Ozkan B., Rougemont J. et al.. Two distinct promoter architectures centered on dynamic nucleosomes control ribosomal protein gene transcription. Genes Dev. 2014; 28:1695–1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reja R., Vinayachandran V., Ghosh S., Pugh B.F.. Molecular mechanisms of ribosomal protein gene coregulation. Genes Dev. 2015; 29:1942–1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rudra D., Warner J.R.. What better measure than ribosome synthesis. Genes Dev. 2004; 18:2431–2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bosio M.C., Fermi B., Spagnoli G., Levati E., Rubbi L., Ferrari R., Pellegrini M., Dieci G.. Abf1 and other general regulatory factors control ribosome biogenesis gene expression in budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017; 45:4493–4506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fermi B., Bosio M.C., Dieci G.. Promoter architecture and transcriptional regulation of Abf1-dependent ribosomal protein genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:6113–6126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhao Y., McIntosh K.B., Rudra D., Schawalder S., Shore D., Warner J.R.. Fine-structure analysis of ribosomal protein gene transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006; 26:4853–4862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Longtine M.S., McKenzie A. 3rd, Demarini D.J., Shah N.G., Wach A., Brachat A., Philippsen P., Pringle J.R.. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998; 14:953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rigaut G., Shevchenko A., Rutz B., Wilm M., Mann M., Seraphin B.. A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nat. Biotechnol. 1999; 17:1030–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Haruki H., Nishikawa J., Laemmli U.K.. The anchor-away technique: rapid, conditional establishment of yeast mutant phenotypes. Mol. Cell. 2008; 31:925–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nishimura K., Fukagawa T., Takisawa H., Kakimoto T., Kanemaki M.. An auxin-based degron system for the rapid depletion of proteins in nonplant cells. Nat. Methods. 2009; 6:917–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jiang C., Pugh B.F.. A compiled and systematic reference map of nucleosome positions across the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Genome Biol. 2009; 10:R109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. David F.P., Delafontaine J., Carat S., Ross F.J., Lefebvre G., Jarosz Y., Sinclair L., Noordermeer D., Rougemont J., Leleu M.. HTSstation: a web application and open-access libraries for high-throughput sequencing data analysis. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e85879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bruzzone M.J., Grunberg S., Kubik S., Zentner G.E., Shore D.. Distinct patterns of histone acetyltransferase and mediator deployment at yeast protein-coding genes. Genes Dev. 2018; 32:1252–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zentner G.E., Kasinathan S., Xin B., Rohs R., Henikoff S.. ChEC-seq kinetics discriminates transcription factor binding sites by DNA sequence and shape in vivo. Nat. Commun. 2015; 6:8733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Berger A.B., Decourty L., Badis G., Nehrbass U., Jacquier A., Gadal O.. Hmo1 is required for TOR-dependent regulation of ribosomal protein gene transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007; 27:8015–8026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang D., Mansisidor A., Prabhakar G., Hochwagen A.. Condensin and Hmo1 mediate a starvation-induced transcriptional position effect within the ribosomal DNA array. Cell Rep. 2016; 14:1010–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sun M., Schwalb B., Pirkl N., Maier K.C., Schenk A., Failmezger H., Tresch A., Cramer P.. Global analysis of eukaryotic mRNA degradation reveals Xrn1-dependent buffering of transcript levels. Mol. Cell. 2013; 52:52–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cipollina C., Alberghina L., Porro D., Vai M.. SFP1 is involved in cell size modulation in respiro-fermentative growth conditions. Yeast. 2005; 22:385–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Laferte A., Favry E., Sentenac A., Riva M., Carles C., Chedin S.. The transcriptional activity of RNA polymerase I is a key determinant for the level of all ribosome components. Genes Dev. 2006; 20:2030–2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Badis G., Chan E.T., van Bakel H., Pena-Castillo L., Tillo D., Tsui K., Carlson C.D., Gossett A.J., Hasinoff M.J., Warren C.L. et al.. A library of yeast transcription factor motifs reveals a widespread function for Rsc3 in targeting nucleosome exclusion at promoters. Mol. Cell. 2008; 32:878–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kubik S., Bruzzone M.J., Jacquet P., Falcone J.L., Rougemont J., Shore D.. Nucleosome stability distinguishes two different promoter types at all protein-coding genes in yeast. Mol. Cell. 2015; 60:422–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kubik S., O’Duibhir E., de Jonge W.J., Mattarocci S., Albert B., Falcone J.L., Bruzzone M.J., Holstege F.C.P., Shore D.. Sequence-directed action of RSC remodeler and general regulatory factors modulates +1 nucleosome position to facilitate transcription. Mol. Cell. 2018; 71:89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rossi M.J., Lai W.K.M., Pugh B.F.. Genome-wide determinants of sequence-specific DNA binding of general regulatory factors. Genome Res. 2018; 28:497–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhu C., Byers K.J., McCord R.P., Shi Z., Berger M.F., Newburger D.E., Saulrieta K., Smith Z., Shah M.V., Radhakrishnan M. et al.. High-resolution DNA-binding specificity analysis of yeast transcription factors. Genome Res. 2009; 19:556–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schmid M., Durussel T., Laemmli U.K.. ChIC and ChEC; genomic mapping of chromatin proteins. Mol. Cell. 2004; 16:147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wallace E.W., Kear-Scott J.L., Pilipenko E.V., Schwartz M.H., Laskowski P.R., Rojek A.E., Katanski C.D., Riback J.A., Dion M.F., Franks A.M. et al.. Reversible, specific, active aggregates of endogenous proteins assemble upon heat stress. Cell. 2015; 162:1286–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pillet B., Mitterer V., Kressler D., Pertschy B.. Hold on to your friends: Dedicated chaperones of ribosomal proteins: dedicated chaperones mediate the safe transfer of ribosomal proteins to their site of pre-ribosome incorporation. Bioessays. 2017; 39:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chedin S., Laferte A., Hoang T., Lafontaine D.L., Riva M., Carles C.. Is ribosome synthesis controlled by pol I transcription. Cell Cycle. 2007; 6:11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Munding E.M., Shiue L., Katzman S., Donohue J.P., Ares M. Jr. Competition between pre-mRNAs for the splicing machinery drives global regulation of splicing. Mol. Cell. 2013; 51:338–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kawahara T., Yanagi H., Yura T., Mori K.. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced mRNA splicing permits synthesis of transcription factor Hac1p/Ern4p that activates the unfolded protein response. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1997; 8:1845–1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Munding E.M., Igel A.H., Shiue L., Dorighi K.M., Trevino L.R., Ares M. Jr. Integration of a splicing regulatory network within the meiotic gene expression program of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 2010; 24:2693–2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Coulombe-Huntington J., Xia Y.. Network centrality analysis in fungi reveals complex regulation of lost and gained genes. PLoS One. 2017; 12:e0169459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wapinski I., Pfeffer A., Friedman N., Regev A.. Natural history and evolutionary principles of gene duplication in fungi. Nature. 2007; 449:54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dinman J.D. Pathways to specialized ribosomes: the brussels lecture. J. Mol. Biol. 2016; 428:2186–2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kondrashov N., Pusic A., Stumpf C.R., Shimizu K., Hsieh A.C., Ishijima J., Shiroishi T., Barna M.. Ribosome-mediated specificity in Hox mRNA translation and vertebrate tissue patterning. Cell. 2011; 145:383–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mauro V.P., Edelman G.M.. The ribosome filter hypothesis. PNAS. 2002; 99:12031–12036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Warner J.R., McIntosh K.B.. How common are extraribosomal functions of ribosomal proteins. Mol. Cell. 2009; 34:3–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Grummt I. The nucleolus-guardian of cellular homeostasis and genome integrity. Chromosoma. 2013; 122:487–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Guimaraes J.C., Zavolan M.. Patterns of ribosomal protein expression specify normal and malignant human cells. Genome Biol. 2016; 17:236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All deep sequencing data sets have been submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under accession code GSE155235.