Abstract

Objectives

To explore the services National Health Service (NHS)-based sport and exercise medicine (SEM) clinics can offer, and the barriers to creating and integrating SEM services into the NHS.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were undertaken to collect data from identified ‘stakeholders’. Stakeholders were identified as individuals who had experience and knowledge of the speciality of SEM and the NHS. An inductive thematic analysis approach was taken to analyse the data.

Results

N=15 stakeholder interviews. The management of musculoskeletal (MSK) injuries (both acute and chronic) and concussion were highlighted as the two key services that SEM clinics can offer that would most benefit the NHS. MSK ultrasound was also mentioned by all stakeholders as a critical service that SEM clinics should provide. While exercise medicine is an integral part of SEM, SEM clinics should perhaps not have a heavy exercise medicine focus. The key barriers to setting up SEM clinics were stated to be convincing NHS management, conflict with other specialities and a lack of awareness of the speciality.

Conclusion

The management of acute MSK injuries and concussion should be the cornerstone of SEM services, ideally with the ability to provide MSK ultrasound. Education of others on the speciality of SEM, confirming consistent ‘unique selling points’ of SEM clinics and promoting how SEM can add value to the NHS is vital. If the successful integration of SEM into the NHS is not widely achieved, we risk the NHS not receiving all the benefits that SEM can provide to the healthcare system.

Keywords: Sports & exercise medicine, Ultrasound, Physical activity

INTRODUCTION

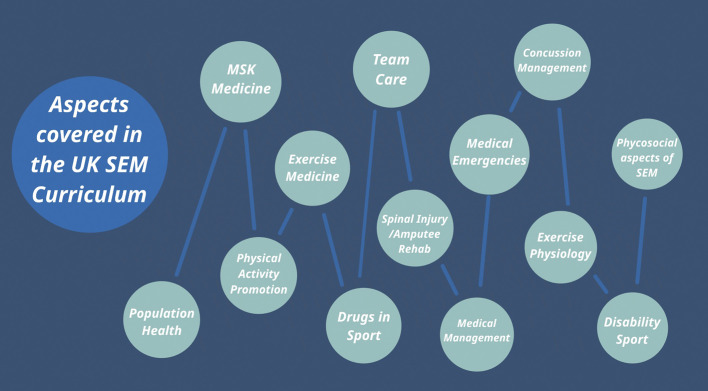

Sport and exercise medicine (SEM) was established as an independent medical speciality in the UK in 2005 as an important aspect of the London 2012 Olympic Games health legacy commitment.1 2 There are many facets to the speciality, which is reflected in the breadth of the training programme (figure 1).3 4

Figure 1.

Key aspects involved in speciality training curriculum for SEM in the UK.4 MSK, musculoskeletal; SEM, Sport and Exercise Medicine.

Decline of SEM in the NHS?

There are now over 147 SEM doctors on the General Medical Council Specialist Register, and every year approximately nine new specialist trainees begin training in the UK.5 6 In recent years, there has been a decline in growth of the speciality, highlighted by a loss of SEM training posts in Scotland and Wales.7 8 This drop can be attributed to several factors such as the loss of momentum following the London 2012 Olympic games (a similar loss of momentum has been observed after previous olympic events).9 Perhaps due to the low number of National Health Service (NHS) SEM posts, the majority of SEM trainees work in the private sector once they become consultants, and, anecdotally, some no longer work within NHS settings at all despite the fact that many view it as a desirable work setting.10

Current relationship between SEM and the NHS

The Faculty of Sport and Exercise Medicine (FSEM) promotes SEM as a cost-effective approach to the prevention and management of illness and injury and is calling for an increase in SEM consultants in the NHS.11 In support of this, one study found that 93% of the clinicians surveyed felt that there was a role for SEM in the NHS.12 Given the training and expertise of SEM consultants, they may be considered well placed to aid the NHS in dealing with high levels of physical inactivity, and the burden placed on the system by musculoskeletal (MSK) issues.11 Current NHS SEM services have been shown to reduce surgical interventions, reduce the number of scans requested and improve patient satisfaction, and can therefore be beneficial to the NHS.13

To establish a mutually beneficial relationship, more clarity is needed over the role of SEM in the NHS. The need to better define how SEM fits into the NHS has been raised for many years.3 7 14 Though several case studies highlight examples of integration across the UK, more research is needed to explore how SEM can be better integrated into the NHS.13 As such, this study aims to explore what individuals working in SEM think about what services an NHS-based SEM clinic could provide that would be of most value, and the barriers to creating and integrating such a service within the NHS.

METHODS

A qualitative approach using semi-structured interviews was used in this study. Research ethics approval was granted from the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee, University of Nottingham (reference: 212-1802; 12 February 2018).

Participants and recruitment

Stakeholder groups were defined based on identifying individuals with experience and knowledge of the speciality of SEM, and of working in the NHS. Participants were recruited (February–April 2018) from these stakeholder groups subject to the inclusion criteria (table 1) using purposive sampling by email.15

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria for the study

| 1. | Belong to a stakeholder group (as per table 2) |

| 2. | Have actively worked in SEM, including: SEM clinics, elite sport, public health, with more than 3 years experience working in SEM or working with SEM practitioners |

| 3. | Have had more than 5 years experience working in the NHS |

NHS, National Health Service; SEM, sport and exercise medicine.

Data collection

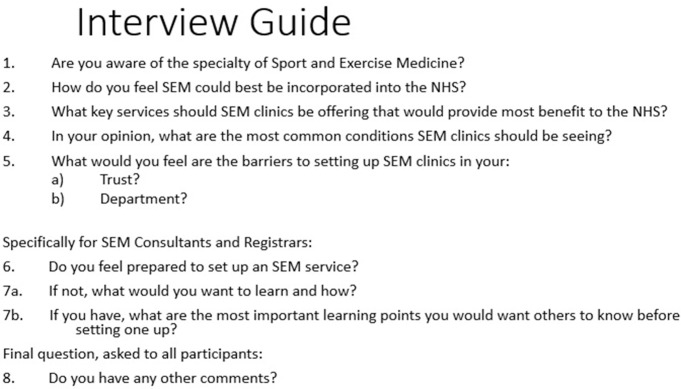

The interview schedule is provided in figure 2. Each participant was given a unique anonymised code. These data were recorded in a key file with the participant speciality (ie, the stakeholder group interviewees’ belong to). No other personal data were recorded. All interviews were conducted by the lead author and digitally audio recorded. All recordings were transcribed verbatim. Any identifiable information discussed during the interviews were redacted from the transcripts. Interviews continued until data saturation was reached.16 17

Figure 2.

Interview guide used for every interview. SEM, sport and exercise medicine.

Data analysis

An inductive thematic analysis approach was taken to analyse the interview transcripts.18 In terms of epistemology, a realist approach was adopted as the research team believed there was likely to be a single truth in answer of the objectives, in keeping with the realist paradigm.19 Braun and Clarke’s six-step process was followed and used to extract meaning and concepts from the data in order to identify patterns, and ultimately generate themes, which were managed using Trello software (version 3.40).20 21 To ensure reliability, two members of the research team started the coding process by reading, five (33%) randomly selected interview transcripts separately and discussed their coding decisions together, working through differences of opinion until a consensus was made. A reflective journal was kept to determine the extent to which thoughts and observations were data-driven and without researcher influence, in order to manage unconscious bias. Once all interviews had been coded and themes had been finalised, five randomly selected transcripts were given to the same reviewers to code to check whether extracts represented the themes appropriately. There was a 79% similarity. A result of over 70% has previously been deemed acceptable.22

RESULTS

Demographic information

Seven stakeholder groups were identified (table 2). Sixteen individuals were invited to participate in the study, and 15 participated (93%) covering all stakeholder groups. The interviews lasted 23 min 10 s on average, ranging from 14 min 38 s to 31 min 03 s. The stakeholders included 4 female and 11 males with an average age of 41 (range 34–47) years. They were all working in the UK.

Table 2.

The seven stakeholder groups and number of participants per group

| Stakeholder group | Participants (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Accident and emergency doctors with an SEM interest | 2 |

| 2. | SEM registrars | 2 |

| 3. | General practitioners with extended role in MSK | 1 |

| 4. | MSK radiologists | 2 |

| 5. | Orthopaedic surgeons | 2 |

| 6. | Physiotherapists | 2 |

| 7. | SEM consultants | 4 |

MSK, musculoskeletal; SEM, sport and exercise medicine.

Interview results from consultants and teaching staff

Five themes and 15 subthemes were identified from the transcripts (table 3).

Table 3.

Themes and subthemes

| Refined themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| 1. Roles believed to be key to being an SEM clinician | 1(a) Demonstrate clinical leadership (7) 1(b) Expert in MSK medicine (15) 1(c) Perform MSK ultrasound (15) 1(d) Provide physical activity (PA) education (10) |

| 2. Services SEM clinics can offer that would provide the most value to the NHS | 2(a) Management of MSK injuries (acute and chronic) (15) 2(b) Management of concussion (11) |

| 3. Sources that SEM clinics receive referrals from (not included in full as deemed not relevant to study objective) |

3(a) A&E (8) 3(b) GP (14) 3(c) Physiotherapists (13) 3(d) Orthopaedics (10) |

| 4. Clinicians’ recognise there are common barriers to setting up an SEM clinic | 4(a) Resistance from management (8) 4(b) Conflict with other specialities (9) 4(c) Lack of awareness of the speciality (15) |

| 5. Learning points for setting up SEM clinics (from Q7b only asked to SEM consultants and registrars (n=6)) |

5(a) Increasing awareness of SEM (6) 5(b) Meeting with the ‘right’ influencers (4) |

In brackets is the number of participants that mentioned the sub-theme.

A&E, accident and emergency; GP, General practitioner; MSK, musculoskeletal; NHS, National Health Service; SEM, sport and exercise medicine.

1. Roles believed to be key to being an SEM clinician

1(a) Demonstrate clinical leadership

Clinical leadership was brought up in the context of incorporating MSK services into the NHS, either through Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) or by showing leadership.

The work could be within CCGs looking at transforming outdated systems and medical management into streamlining conservative treatment of MSK issues. Participant 8.

SEM doctors should ‘be able to show medical leadership within MSK medicine’ (participant 5).

1(b) Experts in MSK medicine

MSK medicine was identified by all participants as a critical service that should be provided by SEM clinics in order to add value to the NHS.

MSK medicine is a vital part of SEM clinics, providing knowledge of MSK injuries and the skill to assess, diagnose and treat. Participant 9

1(c) Perform MSK ultrasound

All participants also identified MSK ultrasound as a service, SEM clinics should offer.

We do diagnostic ultrasound, it saves the patient having to go through a radiology department. Participant 13

The ability of SEM clinicians to manage MSK issues and be able to also use ultrasound to aid with diagnosis and treatment (via ultrasound-guided injections) was seen as valuable by nine participants, with one participant describing an SEM clinic as a ‘one-stop shop’ (participant 7).

1(d) Provide physical activity (PA) education

Various participants maintained that SEM clinicians should be involved in providing and promoting education regarding PA.

The advice regarding PA, I think there’s a massive need for this going forward. Participant 11.

However, the best way for SEM clinicians to promote PA was unclear.

I think there are different ways of promoting PA—do you need a separate clinic? I’m still myself trying to work out how it will work as a job role for a SEM doctor. Participant 9

In regard to how best exercise medicine should be promoted, several participants mentioned it should be done as part of wide-spread public health initiatives and that large organisations are already taking lead on this.

There’s a definite role for exercise medicine in public health. Participant 6.

The Faculty {FSEM} have taken on the role of educating on PA. Participant 8

2. Services SEM clinics can offer that would provide the most value to the NHS

The management of non-surgical MSK injuries (both acute and chronic) and concussion were highlighted as the two key areas in which SEM could add the most value to the NHS.

2(a) Management of MSK injuries (acute and chronic)

Regarding the management of MSK injuries, one participant highlighted the challenges of managing acute MSK issues in accident and emergency (A&E) settings owing to time pressures.

It is very difficult to fully assess MSK injuries’ and that it was a good idea to ‘have a clinic to follow that up because people have got more dedicated time. Participant 14

2(b) Management of concussion

Concussion was flagged up by over half of the participants as an opportunity to incorporate SEM into the NHS. Many highlighted the poor knowledge around concussion management and that concussion clinics ‘could be an extra service that an SEM Consultant would be well trained to deliver’ (participant 6).

In the next 10years, we’ll see more NHS Concussion Clinics. Participant 8

4. Clinicians’ recognise there are common barriers to setting up an SEM clinic

4(a) Resistance from management

When asked, over half of the participants posited that managers were one of the biggest barriers to integrating SEM services into the NHS. It was felt that managers are under increasing financial strain and they

would have thought sports would have to be rationed for more serious medical conditions. Participant 13

The majority of participants reiterated the idea that it can be ‘difficult to innovate’ (participant 3) within hospital settings and getting managerial approval for creating change in hospitals can be difficult.

A lot of the NHS is resistant to change and because SEM is still quite new, there are already a number of established pathways. Participant 15

4(b) Conflict with other specialities

Several participants commented on the concept of SEM being perceived as encroaching onto other specialities and ‘pinching work’, which may result in other specialities being ‘resistant to us’ (participant 11).

For example, with ultrasound, we may be taking away from interventional radiology. Participant 12

Radiology and orthopaedics were singled out as the two specialities most likely to be affected by this issue.

People are worried about their own specialty so that would be orthopaedic surgeons, physios, radiologists who don’t want to be de-skilled or lose the areas of interest that they have themselves. Participant 1.

4(c) Lack of awareness of the speciality

The lack of awareness of the SEM speciality was commented on by several participants as a barrier to integrating it into the NHS.

I think it’s lack of familiarity because people won’t know what you can do and what you can offer.’ Participant 4

Most health professionals are ‘unaware of the specialty (participant 10).

SEM does not have ‘an identity as to where they sit (participant 3).

It was mentioned that if potential sources of referrals to SEM clinics have a lack of awareness of the speciality will result in a lack of engagement with the SEM service.

Potential sources of referrals ‘don’t really know what they should be referring’ (participant 15).

5. Leaning points for setting up SEM clinics

5(a) Increasing awareness of SEM

Participants provided solutions for many of the identified barriers which included education of a range of stakeholders and referring professionals.

few people know SEM services exist and even less know what sort of things and patients should be referred to them. Participant 9

5(b) Meeting with the ‘right’ influencers

In addition, when setting up a service, advice from one of the participants included meeting the medical director to ensure the issue is being discussed with the right influencers.

it was a big learning experience for me… if I was to do it again I would want the big influential people on board from the get go.’Participant 1

DISCUSSION

This research has provided three key findings. First, the key services that SEM clinics can offer the NHS are in the management of MSK injuries and concussion. Second, the main barriers to setting up a SEM clinic are getting managerial agreement, conflict with other specialities and a lack of awareness of the speciality. Third, the main perceived solution to reducing the impact of the identified barriers is to improve education among the medical profession about the speciality of SEM.

Defining a place for SEM in the NHS

The management of MSK injuries and concussion were highlighted as the two key areas in which SEM services can provide useful services to the NHS. Regarding MSK injuries, this includes both acute injuries usually presenting via A&E, and chronic injuries usually presenting via general practice. The benefit of utilising MSK ultrasound and injection therapies in the management of MSK injuries was also identified by several stakeholders as a key service that SEM clinics can provide. MSK consultations are thought to account for nearly 30% of all general practice consultations with nearly 82% not requiring surgery.23 24 These patients will therefore typically re-present in general practice recurrently which is an inefficient use of NHS resources.14 SEM consultants play a key role here in non-surgical management, enabling cost-saving and improved pathways for patients.13 Regarding the presentation of acute injuries, A&E departments are notoriously time pressured and overworked.25 26 Fundamentally, A&E does not have enough time to assess acute injuries thoroughly, and the acute swelling post injury means A&E potentially is not the ideal setting to assess certain injuries. Given that 7.7% of A&E attendances are directly related to playing sport, SEM clinics may result in reduced workload for overstretched A&E services without the need to outsource to private care.27

Concussion is well covered on a SEM syllabus and the management of concussion was also highlighted as a key service that SEM clinics could provide.4 Concussion is also a common presentation, and given the majority of GPs and A&E doctors do not feel confident in how to manage it, this is an area that SEM clinics could help relieve pressure from overloaded departments.28–31

SEM, exercise medicine and the NHS

Physical inactivity costs the UK economy over £7.4 billion a year.32 To begin to address this, FSEM recently launched ‘Moving Medicine’, a website designed to support healthcare professionals integrate PA advice into clinical practice.33 For the day-to-day clinical work of a SEM doctor, it is unclear exactly what an exercise medicine service within the NHS could, or should, look like, and whether SEM clinics should facilitate exercise medicine. The value of exercise medicine is not being debated, rather the question is regarding the most effective method and setting for delivering it.34 While it is always essential to provide brief PA advice where appropriate as per NICE guidance, the findings of this study suggest SEM clinics may not be the most effective setting for having a heavy exercise medicine focus.35 SEM clinicians of course have a responsibility to promote, integrate and facilitate exercise as medicine within society and the healthcare system. However, exercise medicine may be best dealt with through public health initiatives to promote both individual and population-level change rather than through individual-level behaviour change promoted through SEM clinics, an idea that has been highlighted previously.36

Key barriers to integrating SEM into the NHS

The need for SEM to build collaborative relationships with other specialities was highlighted in this study and has been emphasised previously.24 37 Caution should be applied to not cross the boundaries of other specialities, but instead take a cooperative approach and explain how SEM can add value. Another major barrier appeared to be awareness of the speciality among other medical professionals. If the knowledge of the speciality is poor, it is hard to cultivate a reputation, resulting in SEM clinics not receiving referrals that should have been sent to the service.

What are the next steps?

The findings of this study have highlighted a key solution to better incorporating SEM into the NHS is to improve education about SEM among the medical profession, a finding supported by previous studies.12 38 It is unsurprising that other professions have a lack of knowledge about the SEM speciality, particularly in relation to how it works as a speciality within the NHS, when the speciality itself appears to not have clear definitions over its place in healthcare. SEM urgently needs to confirm its identity within the NHS.

Despite the barriers mentioned in this study, several SEM services are already in place.13 It is important to ensure that the value of SEM clinics is observed and documented to ensure they continue to be funded by the NHS. Otherwise, we risk the NHS not benefitting from the services that SEM clinics can offer.

Strengths and limitations

This study had several strengths including a high inter-rater reliability to ensure trustworthiness of coding, achieving data saturation (despite a limited number of interviews conducted) and utilising a qualitative design to uncover insightful data. As ever, there were limitations such as the potential influence of the interviewer on data collection and analysis. A reflective journal was kept to minimise this. Interview participants were selected depending on them being viewed as a stakeholder by the research team and was therefore open to selection bias. It may have been beneficial to get the views of other SEM-related specialities such as podiatrist, chiropractors and osteopaths. In addition, opinions could be explored from individuals that work outside of the NHS, policymakers or government figures. It would have also been of benefit to interview patients that had attended SEM clinics to explore what they thought of the services they had received. Future studies could consider seeking opinions from a broader range of stakeholders.

CONCLUSION

This study has provided data that supports the management of MSK injuries and concussion as the two key areas in which SEM clinics can offer valuable services to the NHS. The management of these two areas should be targeted as the ‘unique selling point’ of SEM clinics, ideally with the ability to provide MSK ultrasound and injection therapies. These clinicians felt that it is more important for SEM clinics to prioritise these services over exercise medicine, which, while highly important for SEM and public health, should be dealt with at a public health, population-based level rather than have a heavy focus in SEM clinics. The perceived barriers to SEM clinics being created were lack of knowledge regarding the speciality from potential referral sources, potential conflict with other specialities, and gaining support from management. This preliminary research can be used to guide further studies exploring how best to integrate SEM into the NHS. If the successful integration of SEM into the NHS is not widely achieved, we risk the NHS not receiving all the benefits that SEM can provide.

Summary box.

What are the new findings?

Providing expert care of MSK injuries and of concussion are deemed the two key services that SEM clinics can provide for NHS.

While exercise medicine is an essential part of the SEM speciality, it should perhaps not be a focus of SEM clinics.

Convincing management, resistance from other specialities and lack of knowledge of the speciality were listed as key barriers to integrating SEM into the NHS.

Educating about SEM clinics is vital to its success. We need more formal clarification of the ‘unique selling point’ of SEM clinics, and this advertised more widely.

How it might help clinical practice in the future?

The findings of this study could be used to influence the SEM registrar curriculum to include information on setting up SEM clinics in order to empower newly qualified SEM consultants to feel more comfortable setting up SEM services.

Better definition on how SEM can be integrated into the NHS could result in more successful SEM NHS services and increased funding into SEM, allowing the healthcare system to benefit more from the services SEM can offer.

Footnotes

Twitter: Dane Vishnubala @danevishnubala and Steffan Griffin @SteffanGriffin.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the final paper. DV, MKP and KE were involved in developing the concept and design. DV carried out all data collection. Analysis of the data was completed by DV and KM. Write-up was contributed to by all authors and further guidance and advice provided by SG, KE, AP, PB and GF.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: There are no competing interests. All associated costs of the study were self-funded by DV.

Patient involvement: Given the nature of the study, no patient involvement was required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was gained from Nottingham University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: The transcribed data are available from DV on request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Weiler R, Jones N, Chew S, et al. Sport and exercise medicine: a fresh approach. NHS Information Document, 2011, 2012.

- 2. Tew GA, Copeland RJ, Till SH. Sport and exercise medicine and the olympic health legacy. BMC Med 2012;10:74 10.1186/1741-7015-10-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cullen M, Batt M. Sport and exercise medicine in the United Kingdom comes of age. BJSM 2005;39:250–1. 10.1136/bjsm.2005.019307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Specialty training curriculum for sport and exercise medicine. Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Boar August 2010. Available https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/sites/default/files/2010%20SEM%20Curriculum%20FINAL%20120417%20V0.19.pdf (accessed 12 Mar 2020)

- 5. GMC specialist register for sport and exercise medicine. Available https://www.fsem.ac.uk/about-us/whos-who/specialist-register/ (accessed 28 Mar 2020)

- 6. Sport and exercise medicine fill-rates 2013–19. Royal College of Physicians. Available https://www.st3recruitment.org.uk/webapp/data/media/5d8dd7ca400de_SEM_fill-rates_2013-19.pdf (accessed 20 Mar 2020)

- 7. Cullen M. Crossroads or threshold? Sport and exercise medicine as a specialty in the UK. BJSM 2009;43:1083–4. 10.1136/bjsm.2009.069187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sport & exercise medicine physician ST3 recruitment. Interview dates and posts. Available https://www.st3recruitment.org.uk/specialties/sport-exercise-medicine (accessed 28 Mar 2020)

- 9. Weed M, Coren E, Fiore J, et al. A systematic review of the evidence base for developing a physical activity and health legacy from the London 2012 olympic and paralympic games. 2009. Department of Health Available http://www.london.nhs.uk/webfiles/Independent%20inquiries/Developing%20physical%20activity%20and%20health%20legacy%20-%20full%20report.pdf (accessed 12 Mar 2020) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10. Seah R. Career intentions of Sport & Exercise Medicine Specialty Registrars (SEM StRs) in the United Kingdom upon completion of higher specialty training. Poster Presentation, 2011.

- 11. Draft WHO global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030 Response from the Faculty of Sport and Exercise Medicine (UK). Available https://www.who.int/ncds/governance/Faculty_of_Sport_and_Exercise_Medicine_UK.pdf?ua=1 (accessed 28 Mar 2020)

- 12. O’Halloran P, Brown VT, Morgan K, et al. The role of the sports and exercise medicine physician in the National Health Service: a questionnaire-based survey. BJSM 2009;43:1143–8. 10.1136/bjsm.2009.064972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sport & Exercise Medicine A fresh approach in practice. A National Health Service information document. Available https://www.fsem.ac.uk/standards-publications/publications/a-fresh-approach-in-practice/ (accessed 12 Mar 2020)

- 14. Pullen E, Malcolm D, Wheeler P. How effective is the integration of sport and exercise medicine in the English National Health Service for sport related injury treatment and health management? J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2019;59:481–8. 10.23736/S0022-4707.18.08389-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Littlewood C, May S. Understanding physiotherapy research. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013: 28. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fusch P, Ness L. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qual Report 2015;20:1408–16. [Google Scholar]

- 17. O’Reilly M, Parker N. Unsatisfactory saturation: a critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research. Qual Res 2012;13:190–7. 10.1177/1468794112446106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Holloway Basic concepts for qualitative research. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 1997: 186. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guba E, Lincoln Y. Chapter 6: competing paradigms in qualitative research In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, Editors. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage, 1994: 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Javadi M, Zarea K. Understanding thematic analysis and its pitfall. J Client Care 2016;1:33–9. 10.15412/J.JCC.02010107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fahy P. Addressing some common problems in transcript analysis. Int Rev Res Open Distance Learn 2001. 10.19173/irrodl.v1i2.321 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Margham T. Musculoskeletal disorders: time for joint action in primary care. BrJ Gen Pract 2011;61:657–8. 10.3399/bjgp11X601541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Curriculum for Sport and Exercise Medicine Training Implementation August 2021. Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians training board. 2019. Available https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/sites/default/files/SEM%20Curriculum%20DRAFT%20070120.pdf (accessed 1 Mar 2020)

- 25. Flowerdew L, Brown R, Russ S, et al. Teams under pressure in the emergency department: an interview study. Emergency Med J 2012;29:e2 10.1136/emermed-2011-200084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bagherian F, Hosseini SA. Burnout and job satisfaction in the emergency department staff: a review focusing on emergency physicians. Int J Med Invest 2019;8:13–20. 10.5455/apd.36379 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. NHS Digital Accident and emergency attendances in England – 2014–15. Available https://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB19883 (accessed 28 Mar 2020)

- 28. National Institute for Clinical Excellence Head injury - background information. NICE guidance, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mistry DA, Rainer TH. Concussion assessment in the emergency department: a preliminary study for a quality improvement project. BMJ Open Sport Exercise Med 2018;4:e000445 10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rashid H, Dobbin N, Mishra S (2020). Management of sports-related concussion in UK emergency departments: a multi-centre study. Poster presentation. Available https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339032575_Management_of_sports-related_concussion_in_UK_emergency_departments_a_multi-centre_study (accessed 1 Mar 2020) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31. Sharp DJ, Jenkins PO. Concussion is confusing us all. Pract Neurol 2015;15:172–86. 10.1136/practneurol-2015-001087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Scarborough P, Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe KK, et al. The economic burden of ill health due to diet, physical inactivity, smoking, alcohol and obesity in the UK: an update to 2006–07 NHS costs. J Public Health (Bangkok) 2011;33:527–35. 10.1093/pubmed/fdr033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moving medicine website. Available https://movingmedicine.ac.uk/ (accessed 28 Mar 2020)

- 34. Iliffe S, Masud T, Skelton D, et al. Promotion of exercise in primary care. BMJ 2008;337:a2430 10.1136/bmj.a2430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. NICE Guidance Physical activity: brief advice for adults in primary care. Public Health Guideline [PH44] Published May 2013. Available https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph44/chapter/1-Recommendations (accessed 17 May 2020)

- 36. Speake H, Copeland RJ, Till SH, et al. Embedding physical activity in the heart of the NHS: the need for a whole-system approach. Sports Med 2016;46:939–46. 10.1007/s40279-016-0488-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Faculty of Sports and Exercise Medicine Specialty training curriculum for sports and exercise medicine. Available https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/SEM_3_Jul_07_v.Curr_0031.pdf_30535131.pdf (accessed 20 Mar 2020)

- 38. Kassam H, Brown VT, O’Halloran O, et al. General practitioners’ attitude to sport and exercise medicine services: a questionnaire-based survey. Postgrad Med 2014;90:680–4. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2013-132245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]