Abstract

Background:

Clinical settings often make it challenging for patients with kidney failure to receive individualized hemodialysis (HD) care. Individualization refers to care that reflects an individual’s specific circumstances, values, and preferences.

Objective:

This study aimed to describe patient, caregiver, and health care professional perspectives regarding challenges and solutions to individualization of care in people receiving in-center HD.

Design:

In this multicentre qualitative study, we conducted focus groups with individuals receiving in-center HD and their caregivers and semi-structured interviews with health care providers from May 2017 to August 2018.

Setting:

Hemodialysis programs in 5 cities: Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg, Ottawa, and Halifax.

Participants:

Individuals receiving in-center HD for more than 6 months, aged 18 years or older, and able to communicate in English were eligible to participate, as well as their caregivers. Health care providers with HD experience were recruited using a purposive approach and snowball sampling.

Methods:

Two sequential methods of qualitative data collection were undertaken: (1) focus groups and interviews with HD patients and caregivers, which informed (2) individual interviews with health care providers. A qualitative descriptive methodology guided focus groups and interviews. Data from all focus groups and interviews were analyzed using conventional content analysis.

Results:

Among 82 patients/caregivers and 31 health care providers, we identified 4 main themes: session set-up, transportation and parking, socioeconomic and emotional well-being, and HD treatment location and scheduling. Particular challenges faced were as follows: (1) session set-up: lack of preferred supplies, machine and HD access set-up, call buttons, bed/chair discomfort, needling options, privacy in the unit, and self-care; (2) transportation and parking: lack of reliable/punctual service, and high costs; (3) socioeconomic and emotional well-being: employment aid, finances, nutrition, lack of support programs, and individualization of treatment goals; and (4) HD treatment location and scheduling: patient displacement from their usual spot, short notice of changes to dialysis time and location, lack of flexibility, and shortages of HD spots.

Limitations:

Uncertain applicability to non-English speaking individuals, those receiving HD outside large urban centers, and those residing outside of Canada.

Conclusions:

Participants identified challenges to individualization of in-center HD care, primarily regarding patient comfort and safety during HD sessions, affordable and reliable transportation to and from HD sessions, increased financial burden as a result of changes in functional and employment status with HD, individualization of treatment goals, and flexibility in treatment schedule and self-care. These findings will inform future studies aimed at improving patient-centered HD care.

Keywords: hemodialysis, end-stage kidney disease, patient-centered care, qualitative research, individualization

Abrégé

Contexte:

Les environnements cliniques rendent souvent difficile l’individualisation des soins pour les patients recevant des traitements d’hémodialyse (HD). L’individualisation réfère à des pratiques reflétant les préférences, les valeurs et les particularités d’un individu.

Objectif:

Cette étude visait à connaître le point de vue des patients, des soignants et des professionnels de la santé sur les défis et solutions à l’individualisation des soins pour les patients hémodialysés en centre.

Type d’étude:

Une étude qualitative multicentrique menée entre mai 2017 et août 2018 sous la forme (1) de groupes de discussion réunissant des patients hémodialysés en centre et leurs soignants, et (2) d’interviews semi-structurées avec des fournisseurs de soins.

Cadre:

Les programmes d’hémodialyse de cinq villes: Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg, Ottawa et Halifax.

Participants:

Tous les adultes suivant des traitements d’HD en centre depuis plus de 6 mois et pouvant communiquer en anglais étaient admissibles, ainsi que leurs soignants. Les fournisseurs de soins avec une expérience en hémodialyse ont été recrutés selon une approche intentionnelle et par la méthode de sondage cumulatif.

Méthodologie:

Deux méthodes séquentielles ont été entreprises pour la collecte de données qualificatives: (1) groupes de discussion et interviews avec des patients hémodialysés et leurs soignants; desquels ont découlé (2) des interviews individuelles avec des fournisseurs de soins.

Une méthodologie qualitative et descriptive a guidé ces interviews et discussions de groupe. Une analyse de contenu classique a permis d’analyser les données recueillies.

Résultats:

Ces entretiens et groupes de discussion ont impliqué 82 patients/soignants et 31 fournisseurs de soins et ont permis de dégager quatre thèmes principaux: l’organisation des séances, le transport et le stationnement, le bien-être socio-économique et émotionnel, l’emplacement et la planification des traitements d’HD. Les principaux obstacles et/ou solutions dégagés pour chacun étaient les suivants: (1) organisation de la séance: manque de matériel privilégié par le patient, configuration de la machine et de l’accès pour l’HD, boutons d’appel, inconfort du lit/fauteuil, options d’aiguilles, intimité dans l’unité, soins personnels; (2) transport et stationnement: manque de service fiable et ponctuel, coûts élevés; (3) bien-être socio-économique et émotionnel: aide à l’emploi, finances, alimentation, manque de programmes de soutien, individualisation des objectifs de traitement, et (4) emplacement et planification des traitements: déplacement du patient de son unité habituelle, court préavis pour les changements d’heure et de lieu pour la dialyse, manque de flexibilité, pénurie d’unités d’HD.

Limites:

Ces résultats pourraient ne pas s’appliquer aux patients non anglophones, aux patients recevant des traitements d’HD hors des grands centres urbains ou résidant hors du Canada.

Conclusions:

Les participants ont indiqué les principaux défis à l’individualisation des soins des patients hémodialysés en centre. Ces défis concernent principalement le confort et la sécurité du patient pendant les séances d’HD, le transport abordable et fiable vers et au retour des séances d’HD, l’alourdissement du fardeau financier en raison des changements de statut fonctionnel et d’emploi, l’individualisation des objectifs de traitement et la flexibilité de la planification des séances d’HD et des soins personnels. Ces résultats guideront la conduite d’études futures visant l’amélioration des soins pour les patients hémodialysés en centre.

Introduction

Individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD) have frequent interactions with the health care system due to the presence of multiple comorbidities1,2 and complications of CKD including diabetes, anemia, and extremely high rates of cardiovascular disease and mortality.3-6 In addition, people with CKD have poor quality of life and low functional status that worsens with kidney disease progression and is lowest in individuals with kidney failure on dialysis.3,7 Providing quality care that meets the needs of each individual patient and which addresses the complex interaction between the multiple factors that affect health and quality of life in people receiving hemodialysis (HD) is a significant challenge for health care professionals.8 This “individualization of care” or “patient-centred care” refers to the customization of a patient’s care to reflect their individual circumstances, values, and preferences.9-11 An individualized (patient-centered) approach to treatment appears to be superior to the traditional disease-based approach.10 Unfortunately, although system-level barriers to patient-centered care likely exist, little work has been done to identify these barriers from a patient perspective, or to guide potential solutions.12,13

The Triple I study aims to explore the challenges to care for individuals receiving in-center HD and to develop and test solutions to these challenges using a mixed-methods approach.14 The study focuses on challenges in 3 specific areas: individualization (as defined above); information provided to patients about their health and health care; and interaction between health care providers and patients.

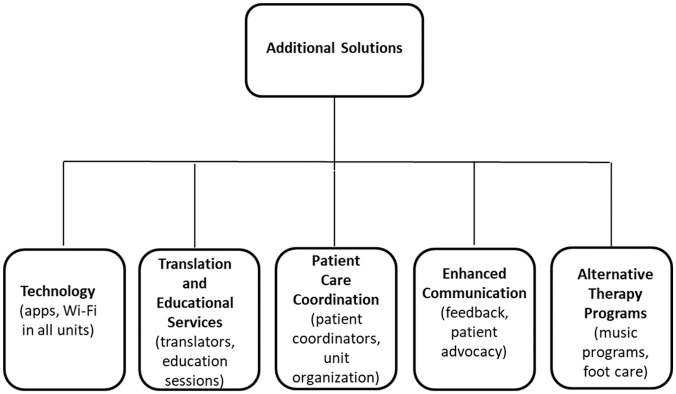

The goal of phase 1 of the Triple I study was to describe patient, caregiver, and health care provider perspectives regarding challenges to individualization of care for people receiving in-center HD and to identify potential solutions to these challenges (Figure 1). Subsequent reports will describe the challenges identified for the information and interaction themes.

Figure 1.

Triple I project overview.

Methods

In phase 1 of the Triple I study, we undertook 2 sequential methods of qualitative data collection: (1) focus groups and interviews with HD patients and caregivers in multiple centers across Canada, which informed (2) individual interviews with health care providers across the country.

Patient Engagement

As with all studies that are part of the Can-SOLVE CKD Network research program, this study was supported by a patient advisory group consisting of 4 patient partners who were integrated into the study team and provided input to the program of research.14 Two patient partners were members of the Can-SOLVE Indigenous Peoples’ Engagement and Research Council (IPERC) to ensure Indigenous representation in the development of the study. Patient partners provided input into all aspects of the study including design of the study and focus group and interview guides, as well as contributing to the analysis of focus group and interview data.

Participant Selection

Participants were recruited between April 17, 2017, and August 1, 2018, from in-center HD units in 5 cities: Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg, Ottawa, and Halifax. The study protocol was approved by the research ethics board at the University of Manitoba for the main Winnipeg site, as well as the research ethics boards at the 4 other participating institutions (University of Calgary, University of Alberta, University of Ottawa, and Dalhousie University).

Individuals receiving chronic in-center HD for more than 6 months, aged 18 years or older, and able to communicate in English were eligible to participate in the study. Hemodialysis staff initially identified potential participants who they thought would be capable and interested in participating and obtained consent to approach for the study. During the recruitment visit, research staff asked patients whether they had a caregiver who may also be interested in participating. Caregivers were defined as either a family member or a significant person in the patient’s life who helped with care provision and was aware of their illness. In-person focus groups were thereafter arranged with patients and/or caregiver participants; however, if focus group attendance was difficult due to patients’ dialysis schedules, inability to travel, or other commitments, an interview was arranged. All patient interviews were conducted in person in the dialysis unit to accommodate patient preference. In addition, a study information letter was distributed and/or posted in the waiting room at participating HD units to identify other interested participants. Participants were excluded if they were unable to communicate effectively in English.

Nephrologists, nurses, and allied health professionals from across Canada with HD expertise were invited by email request and/or in person to participate in semi-structured interviews to promote a diversity of demographic and clinical characteristics. Health care providers were recruited using a purposive approach supplemented by snowball sampling, where key stakeholders in nephrology were asked to recommend nephrologists, nurses, and allied health professionals who have expertise in HD to participate in this study.

Data Collection

All participants completed a demographics questionnaire, and provided written informed consent, which included consent to audio recording of sessions, prior to the commencement of their focus group session or interview. The interview and focus group guides were developed based on the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute (OHRI) needs assessment guidelines and existing literature with the input of the study patient partners.15

Patient/caregiver interviews were 30 to 60 minutes in duration, whereas focus groups were 90 to 120 minutes. One facilitator moderated all but one of the focus groups and two of the interviews (K.S.). In this manner, data and information collected from earlier sessions were used to inform subsequent focus groups and interviews. Remaining sessions were facilitated by a senior member of the research team experienced in qualitative research methods (J.F.). Moderators did not have pre-existing relationships with participants. Focus group participants were reimbursed for their time and travel expenses.

Health care providers completed semi-structured face-to-face or telephone interviews lasting 30 to 40 minutes. One interviewer conducted all interviews (K.S.). The challenges and solutions generated by patients and caregivers in the focus groups informed the interview questions with health care providers, specifically to identify potential barriers or facilitators to the implementation of solutions from the health care provider perspective.

All focus groups and interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriptionist (C.R.). A research associate at each participating site served as an observer and recorded field notes on group dynamics, discussions, and interactions during the focus groups. The interviewer wrote field notes during the interviews to supplement recordings.

Data Analysis

Three research associates (J.F., K.S., and K.R.) inductively analyzed each of the patient/caregiver and health care provider transcripts using conventional content analysis, the goal of which is to allow categories to emerge directly from the data rather than using preconceived categories.16,17 We used qualitative description to guide the analysis to allow for new insights to become apparent.18 Each research associate independently reviewed and coded the transcripts using NVivo Pro Version 11 (QSR International Pity Ltd).19 The research associates met with the co-principal investigators (C.B. and M.T.) to discuss and reach consensus on emerging codes and themes, and then systematically applied the agreed-upon codes and themes to all transcripts. The investigators then met again to reduce the codes further and they continued this process until they reached thematic saturation and agreed upon a final set of codes. The process was reflexive and interactive as data analysis continually evolved. The patient partners reviewed several transcripts and approved the themes and codes that were finalized.

Results

We conducted 8 focus groups and 44 interviews with a total of 113 individuals. The focus groups consisted of 47 patients and 18 caregivers (total, n = 65; Winnipeg, n = 29; Halifax, n = 19; Edmonton, n = 13; Ottawa, n = 4). The number of participants in the focus groups ranged from 4 to 13. In Calgary, interviews were conducted with patients in lieu of focus groups (n = 13), and in Edmonton, patient interviews supplemented focus groups (n = 4). Overall, 21 participants on HD (33%) and 13 caregivers (72%) who participated in the focus groups and interviews were female. The median age of patient and caregiver participants was 60 (interquartile range [IQR] 51,74) and 65 (IQR 56,68) years, respectively. Median time on in-center HD was 3 (IQR 1,6) years (Table 1). In addition, 31 health care providers (Winnipeg, n = 13; Halifax, n = 4; Edmonton, n = 3; Calgary, n = 8; Ottawa, n = 3) participated in interviews. Health care providers were 77% female (n = 24) and had been in practice for a median of 13 (IQR 6,16) years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Characteristics (n = 113).

| Patients | Caregivers | Health care providers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall participation, n (%) | 64 (57) | 18 (16) | 31 (27) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 21 (33) | 13 (72) | 24 (77) |

| Male | 43 (67) | 5 (28) | 7 (23) |

| Age (years) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 60 (51,74) | 65 (56,68) | — |

| Location, n (%) | |||

| Calgary | 13 (20) | 0 (0) | 8 (26) |

| Edmonton | 14 (22) | 3 (17) | 3 (10) |

| Winnipeg | 22 (34) | 7 (39) | 13 (42) |

| Ottawa | 3 (5) | 1 (6) | 3 (10) |

| Halifax | 12 (19) | 7 (39) | 4 (13) |

| Time on in-center hemodialysis (years) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 3 (1,6) | — | — |

| Years in clinical practice | |||

| Median (IQR) | — | — | 13 (6,16) |

Note. IQR = interquartile range.

We identified 4 major themes: session set-up; transportation and parking; socioeconomic and emotional well-being; and HD session location and scheduling.

Session Set-Up

Challenges

Patients commented on discomfort during the HD session. Some patients stated the chairs created or aggravated pre-existing pain and HD symptoms, such as back pain and leg cramping: “Like the chairs, I found them totally uncomfortable . . . for a while there, my back was really killing me in those chairs” (ID P18). Some patients found the physical set-up of HD stations problematic—in particular, the placement of the dialysis machine on the opposite side to one’s HD access which resulted in the dialysis lines crossing over patients’ bodies during treatment sessions. In units that did not have bedside call bells, one patient commented on their inability to convey the need for assistance to health care staff during treatment. Patients also discussed needling, including one patient who indicated their fear of needles, and another who expressed their anxiety about their arm looking deformed after receiving multiple needles. Other discomforts patients commented on included the availability of blankets, positioning of televisions, and lack of privacy to discuss sensitive issues in the HD units.

Health care providers reiterated many of the discomforts patients expressed and commented on the poor condition of chairs in some units:

Well the chairs are old . . . some of them don’t work like they should. That’s getting, I think to be a bit more of an issue sometimes if the arms don’t move where they are supposed to . . . (ID H18)

Health care providers also noted that lack of privacy was a significant challenge for patients in the HD units.

Solutions

One patient mentioned that call buttons should be implemented in their particular HD unit to improve patient safety. In addition, new chairs, and equipment were identified as a priority for patient comfort:

. . . There’s only so many of the new chairs . . . (that) make it so that I can sit for long enough . . . and there were a few times that I ended up having to leave before my 3-1/2 hours, because I could only sit for 2. So, there should be more of these (chairs) . . . It shouldn’t be about the money it should be about the patients . . . I certainly have enough on my plate, I don’t need to come here and worry they can’t afford to look after me. (ID P12)

Some patients proposed more opportunities for self-care during HD, including self-needling.

Transportation and Parking

Challenges

The availability of flexible, reliable, and affordable transportation to and from HD sessions was consistently identified as a major issue for patients and their caregivers. Patients communicated that traveling to HD sessions and parking was extremely expensive and many felt it was unfair for them to incur these expenses:

. . . I don’t want to park three blocks away when it’s 40 below and I’ve got to walk, or use my walker, so I think they shouldn’t be charging for parking; you are here because of necessity. So, it’s kind of unfair, I think. (ID P41)

In addition, many patients must wait for public transportation—sometimes for hours—and the interaction between transport and HD schedules may be problematic, either because transport arrives late/departs early, or transport is missed when HD sessions are longer than anticipated due to complications or acute medical issues. Health care providers also identified transportation and parking as challenges for patients, stating that many patients suffer financial hardship due to these costs.

Solutions

Patients expressed the need for improved service from medical transportation programs and improved access to such programs. Patients and health care providers identified parking expenses as a major financial stressor that should be covered or reimbursed by the program or government. According to interviewees in one jurisdiction, parking has been subsidized for HD patients: “Transportation is a huge issue here . . . we give our patients all parking passes so that they don’t have to pay when they come for treatment” (ID H21).

Socioeconomic and Emotional Well-Being

Challenges

Patients and caregivers identified that patients receiving HD often face financial challenges, inadequate nutrition, lack of social support, and non-individualization of treatment goals. Hemodialysis treatment requires substantial changes in lifestyle and activities. Participants reported experiencing a substantial decrease in income due to the inability to work or the need to adjust working hours to accommodate HD sessions:

See the waiting time that we are on for the dialysis to get a new kidney (transplant), you know a lot of people, their incomes drop significantly within the first five to eight years . . . and we don’t eat properly because we can’t afford it, because we are paying rent, and we are paying a vehicle payment or what have you . . . (ID P56)

This reduction in income can significantly affect multiple aspects of patients’ lives, including the ability to afford appropriate foods to comply with HD diets or proper housing. Patients additionally discussed receiving inadequate income allowance or supplementation—such as pensions and disability payments. Furthermore, many individuals relocate from their home communities to begin HD, and they identified a need for more support with social programs as a key priority, since they may not have family members nearby to support them.

Likewise, health care providers conveyed that patients suffer financially due to their inability to return to full-time work once they begin dialysis treatment. Some patients are unable to afford the necessities—such as rent and electricity—and as a result, they may sacrifice proper nutrition and medication for themselves and/or their families:

I’ve talked with patients who have limited income and some months they are trying to choose whether they pay the rent or they pay their light bill, what food they might be able to afford after that, a lot of them have family. So a lot of patients will go without to see that family members are taken care of. Those things trickle down into buying things like iron tablets and Tums, and other over-the-counter medications. (ID H27)

Providers said that even though they teach patients about healthy lifestyles, lack of adherence is often not due to patients’ lack of knowledge or unwillingness to cooperate, but rather that they are simply unable to afford good quality food and medical supplies.

Health care providers also identified that some patients experience a lack of control with commencement of HD, not only in terms of control over tangible or physical resources but also social and psychological control. They find it difficult to cope with crises that may arise, as well as changes in their quality of life.

Finally, health care providers noted that patients do not have individualized treatment goals, but rather must conform to the same plan, even though, in reality, each patient has different circumstances:

There are some people for which dialysis is a bridge to transplantation and then there are people where dialysis is an end modality and they are not well, so we need different approaches for, what are the goals for those individuals. (ID H23)

Solutions

Patients and health care providers suggested the need for financial support for individuals on HD: “There should be a guaranteed living allowance like they have in Sweden and that, where you can live decently” (ID P55). Patients and providers also recommended the development and availability of affordable exercise programs and facilities (including implementing mandatory programs) that might provide social support and improve the well-being of individuals on HD, but recognized challenges associated with sustaining such programs:

It’s a challenge to get biking program implemented (because there) has to be somebody in charge of a biking program . . . There’s benefits that we know that biking on dialysis helps with, particularly people who’ve had restless legs, just to try to help build muscle mass. I think it would be a great addition if we could have that in all programs available to patients. (ID H11)

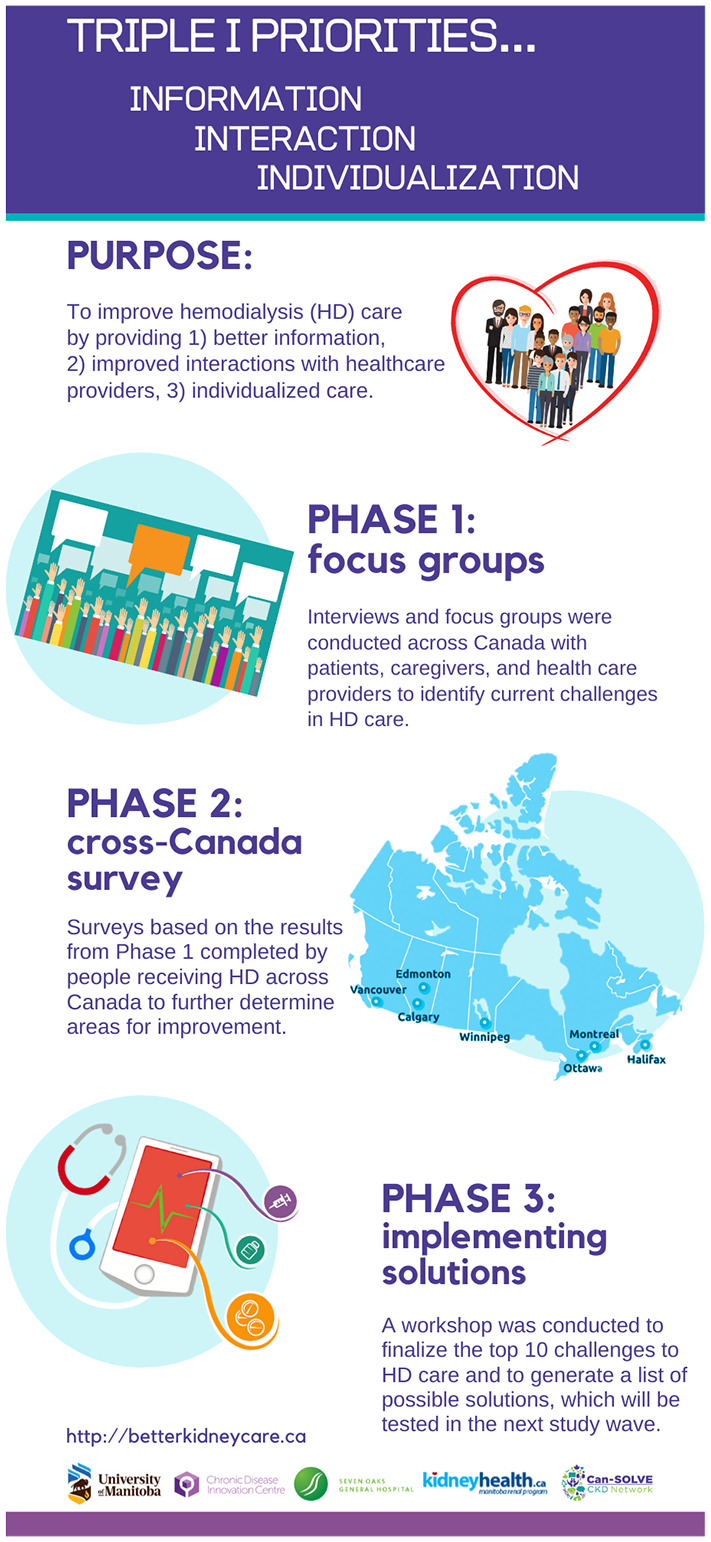

Peer support programs were also identified as possible solutions. Some patients also suggested providing snacks in the HD unit. Finally, health care providers suggested that it may be more appropriate to tailor health care strategies to each patient’s individual needs instead of implementing a treatment program that is similar across all patients (see Figure 2 for additional solutions).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of additional solutions obtained from participant interviews.

Hemodialysis Treatment Location and Scheduling

Challenges

Some patients voiced that they should be able to change their HD schedule to suit their needs; for example, it is challenging for employed patients to attend their dialysis sessions that are scheduled for them. Patients and caregivers in one jurisdiction indicated last-minute changes to their dialysis appointments by the HD unit, as well as displacement from their usual HD spots or units as challenges. They said that it is difficult for patients to rearrange their schedules on short notice given that public medical transportation often requires more than 24 hours’ notice for scheduling changes:

. . . inevitably we get a telephone call. He’s scheduled for 6 o’clock. We get a telephone call, “Oh could you come now for one.” They know he comes (by medical transport), “Oh do you think you could come a little bit earlier.” . . . He goes, “No I can’t.” (ID P60)

Health care providers also identified that these issues had a negative impact on patient well-being and acknowledged that this issue affects health care providers’ ability to see patients in a timely manner.

The lack of beds/chairs and limited capacity of dialysis spots was identified as a common cause for disruption to patients’ regular HD schedules as well.

Solutions

The ability to independently change and modify the HD schedule online or through a central telephone booking number is a possible solution to the challenges voiced above by both health care providers and patients. This would especially foster the needs of employed HD patients:

I don’t think we should assume that it’s going to overcome every potential problem, but you could even imagine scheduling for hemodialysis that if people wanted to change their schedule they could go on(line) and look to see if there is an open spot and then switch themselves into that spot. (ID H31)

See Table 2 for additional quotes.

Table 2.

Selected Quotes About Challenges From Patients, Caregivers, and Health Care Providers.

| Theme | Illustrative quotations |

|---|---|

| Session set-up | |

| Preferred supplies | “Yes, definitely we need the warm blankets, I don’t think I can do dialysis without the warm blankets.” (ID P17) |

| Machine and HD access set-up | “Well I know on this unit I keep saying that this machine is on the wrong side. I shouldn’t have to deal with feeling seat belted in because the tubes go across my lap and to be on the other side, and they say well the TVs there and everything else, the plug in is all over there and that would be too hard to move. But I think if it was more accommodating that way.” (ID P10) |

| Call buttons | “We have no call buttons, so if I need the nurse I need to yell. I don’t talk very loud and so sometimes it takes a bit before they hear me, especially when I was in the corner. So maybe something like a call button if we need the nurse . . . So, I think that’s something that should be addressed. A safety issue actually.” (ID P11) |

| Bed/chair discomfort | “. . . they had some completely new chairs and it makes it much easier for the patients to get comfortable, especially when you are sitting here for four hours. It gets really uncomfortable at times trying to adjust these old chairs because they are all manual where the new ones are electric, so you just push a button to go up or down or, whatever. That would help.” (ID P13) “. . . Now, because there is not enough beds available in dialysis stations, what we have to do, unfortunately, is to disrupt this routine (schedule)—and you know how important a routine can be especially for the elderly . . .” (ID H02) |

| Needling options | “I’ve got a fear of needles . . . if I get a needle in a vein, I’m like a worm on a fishhook.” (ID P7) |

| Privacy in the unit | “. . . and the only other thing is that we do have limited privacy. I know everybody in my pod, when the doctors talk and the pharmacists talk, I know their business and I get it, we don’t have a lot of privacy, but if they could speak a little lower . . .” (ID P35) “. . . most of the dialysis units are kind of an open concept, to disclose information or to have private conversations can be very difficult for patients if you are doing that in the dialysis unit. So, that’s one area that’s difficult . . .” (ID H10) |

| Self-care | “. . . one unit I wish they would bring back is the self-care unit. So that’s the unit they used to have where you would walk in, you would set your machine up, put yourself on, take yourself off, and then you would strip the machine, take all the tubes out and someone else would come . . . They really got rid of that unit and when I was in that unit, three people started needling themselves to get into that unit, because there are no waiting times . . . You do all your own charting and everything. That was a program that I loved. I miss that program . . .” (ID P75) “I like the self-care. I come in the morning, I set-up my machine, I needle myself, I put myself on. The nurses are there if I have an issue and so, dialysis isn’t fun regardless, but I think self-care is really an option . . .” (ID P92) |

| Transportation and parking | |

| Time consuming | “Yes, (medical transportation) is poorly managed. (Medical transportation) should be picking up dialysis patients, instead of picking up all patients. Like, they do have enough systems set in place that, like I’ve sat with patients downstairs because they have been sitting there for 45 minutes to an hour.” (ID P37) |

| Unreliable | “There was a lady there the other night that was waiting 12 hours . . . For an ambulance to come get her after dialysis. She got off at noon and she was still there when she got off that night.” (ID P42) “If they actually did the (transportation) scheduling to have any resemblance to sanity, right . . .” (ID P40) |

| Late for runs | “We have a young lady that if she doesn’t get on by a certain time she has to cut it short. She doesn’t get on long enough to get her four hours. She has to come off.” (ID H43) “Like there’s always a chance of running into time issues which would make patients treatment start late and then if they have some sort of arranged transportation then they wouldn’t get their full treatment and that understandably would make them upset.” (ID H16) “. . . if my ride’s at 1:30 and if I have any troubles . . . I’m cutting time on my machine in order for me to catch my ride.” (ID P45) |

| Expensive | “No, but I, it’s a huge problem like you are saying. I can think off the top of my head, probably like 10 or 15 patients from my shift alone, who have such a difficult time financially and also in terms of transportation, maybe they can only come you know, they can only get a ride at certain times and they have to pay for an ambulance because they just make a little more money than the cut-off, and they can’t afford the ambulance, they don’t have transportation otherwise.” (ID H22) |

| Socioeconomic and emotional well-being | |

| Employment aid | “There should be . . . (some financial support), . . . anything dealing with health takes away from income. With us doing dialysis, we have three, some of you three, four, five days a week. I work during the day now, I work three hours a day so I get some income coming in. But, the first three years I didn’t work at all because nobody would hire me again because I’m gone for three days a week. I’m gone, I can’t work and there it goes, he can’t work., ‘Oh no, we can’t do that because you can’t be here part time’.” (ID P57) |

| Finances | “It’s financial . . . that should be implemented through provincial health to help the patients in the dialysis units. It has to be implemented somehow to help them financially because what you get from disability, CPP, does not help you feed yourself. Like a diet program.” (ID P54) “If they were . . . in the workforce, sometimes they are very debilitated with their disease and are not able to go back to work once they start dialysis, so then not only from a practical standpoint of earning money, but just from social, psychosocial perspective of you know, having been the person who was in control of their life and that loss of control and financial security, there are just so many things that the patients sometimes didn’t understand that this might happen to them, or not prepared to be able to deal with those crisis situations that can arise, or that change in their quality of life and even simple things like food security for some of our patients. And, when you add them all together it can be quite overwhelming . . .” (ID H26) |

| Nutrition | “I mean, if you are somebody who doesn’t have good food security then people need to turn to foodbanks and in the foodbank you get what you get. I’ve talked with patients who have limited income and some months they are trying to choose whether they pay the rent or they pay their light bill, what food they might be able to afford after that, a lot of them have family.” (ID H27) |

| Lack of support programs | “And when a person, when I am not capable of it, when I am that sick. I didn’t have a family member to be there, I had family members in general that was kind of helping, but not like that . . .” (ID P52) “. . . I had a close friend that I kind of built a relationship in the previous unit, we worked out together. He unfortunately passed away, he had cancer and some other issues. He was a good guy. You know it’s neat when you find other active people, same age, and you can place, even other ages, you place them and you are all biking together and stuff, you know, but I’m a relationships person, so it’s kind of, yeah it’d be a little bit good to maybe merge those together a bit.” (ID P19) |

| Hemodialysis (HD) treatment location and scheduling | |

| Patient displacement | “Issues for me were that I was constantly being moved between (units), and never informed. I would go to (one unit) and then they would say, ‘Oh sorry, you are at (a second unit) today’ . . . and then I would be at (the second unit), and they would be, ‘Oh sorry, did nobody call you?’ I would be like, ‘No, nobody called me, the patient’. . . . I don’t feel cared about if you are not telling me where to go for this traumatizing treatment.” (ID P59) “They did that to him for the longest time. He started at (one unit) in the evening and then it’s like, ‘Oh we have an emergency here so we have to put you at (a second unit)’.” (ID P62) “After they’ve been there awhile they tend to get a spot and that’s kind of theirs, but they don’t always get what they want because we don’t always have it. Some people prefer the beds at the (this) unit but they are stable and we need people to be at the (other) unit . . . So if they are stable, they don’t always have a choice of where they are going to be.” (ID H20) “. . . I would say the one thing that has consistently come up, that I’ve heard, . . . from the patients that I do see . . . they hate getting moved . . . this takes a big piece of your life to be on dialysis, and so to have a spot that . . . you can try and manage your life around it. But when you are . . . getting moved between units, because we are in a massive, space crunch . . . they need to commute much farther to get their dialysis, and that is consistently, the piece that I think, it’s the most disruptive for patients.” (ID H15) |

| Short notice changes | “. . . then he’d end up being there and then well, ‘Can you come in the morning, can you come in the afternoon?’ and then it was back to (the first unit), and then it was, then they looked like they were trying to get him permanently at (the second unit) and I said, ‘You know what, as long as they put you on days, go there. I’m tired of this bouncing around’.” (ID P62) “. . . dialysis is usually done historically, has been done Monday, Wednesday, Friday, or Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday, three times a week, either in the morning, or in the afternoon, or in the evening. Now, because there is not enough beds available in dialysis stations, what we have to do, unfortunately, is to disrupt this routine — and you know how important a routine can be especially for the elderly — and what happens is that they don’t know at the beginning of the week, which day dialysis will be for that week because sometimes it can be rather than Monday, Wednesday, Friday, it can be Monday, Thursday, Saturday, that week. It can be one day in the morning, one day in the evening . . .” (ID H02) “One thing I do find challenging . . . is we are running low on dialysis spots . . . and we are needing to shuffle patients quite a bit, so I would look at the dialysis schedule in the morning and see that (a patient is on HD) in the afternoon, and then wait to the afternoon to go and see him, but really they switched him to mornings and it wasn’t reflected on the schedule, and I missed him. Things like that happen a lot.” (ID H14) |

| Lack of flexibility | “But, you can’t come for dialysis when you want, you have to come when you are told and you have to sit in a chair that you are told, and you have to wait in the waiting room until that chair or bed is ready. I mean, we demean patients in this process, and I don’t know if it was you or someone else, but I was having this conversation about a month ago and the idea is that dialysis should be more along the line of booking a golf tee off time or a tennis court.” (ID H24) |

Discussion

From the perspective of patients, caregivers, and health care providers, the key challenges to individualization of in-center HD care were as follows: session set-up, transportation and parking, socioeconomic and emotional well-being, and HD treatment location and scheduling. Challenges within these 4 themes focused on lack of comfort and safety, financial burden related to HD treatment and adapting to change in functional and employment status, lack of individualization of treatment goals, and limited opportunities for flexibility with treatment schedule and self-care.

Our study provides a range of important challenges that raise substantial issues for individuals on HD and potential solutions that can be tested to improve patient-centered care in clinical practice.9 In contrast, most previous studies in this area have focused on more general research-related priorities or uncertainties.

In a mixed-methods study by Manns et al exploring research uncertainties in individuals at or nearing dialysis, patients, caregivers, and health care providers identified 10 research priorities that included enhancing communication between patients and health care providers, improving access to transplantation, management of symptoms, and the effect of dietary constraints on important outcomes, among others. Only one priority identified in the Manns et al study specifically addressed individualization of care—“How do different dialysis modalities compare in terms of their effect on quality of life, mortality, and patient acceptability, and are there specific patient factors that make one modality better for some patients with kidney failure than others.”20

In a qualitative study by Newmann and Litchfield exploring how to improve the quality of care for HD patients, the challenges and suggestions for improvement to care were similar to those identified in our study. In particular, these included transportation and financial issues, and psychological adjustment to a new lifestyle.21 In the latter study, behavior modification and patient education were suggested as the primary solutions to the patients’ concerns, rather than changes at the system level. In contrast, our study identified practical solutions to address specific system-level challenges to individualized care in HD.

The need for increased access to self-management opportunities has been identified in other HD populations. For example, a program to improve person-centered care has been implemented in the United Kingdom, in which patients are encouraged to engage in shared care, where the health care team offers the choice, support, and training for patients to participate in the tasks related to their HD treatment at individualized levels. Tasks include preparing the materials for vascular access, setting up the dialysis machine, inserting fistula needles, or connecting HD lines, among others.22 Similar to our findings, transportation has been identified as a major factor in missed and shortened dialysis treatments due to transportation arriving late to pick up patients. This may subsequently result in detrimental patient health outcomes, including increased hospitalizations due to patients not receiving their scheduled treatments.23

Reliable and consistent transportation to dialysis sessions was voiced as a major issue by HD patients and constitutes a significant source of stress, especially concerning potential missed treatments.24 Furthermore, an observational study of almost 200 000 individuals receiving chronic HD in the United States noted a 20% increased risk of missing HD in individuals who came to dialysis with public transportation compared with those who used private means of transportation.25 A recent report from the National Academy of Sciences identified similar issues with poor reliability of publicly available dialysis transportation which led to patient and caregiver stress and affected HD care.26

The Kidney Foundation of Canada recently conducted a survey documenting financial hardship in individuals undergoing HD.27 Their findings show that the increased financial burden can be attributed primarily to transportation to and from dialysis treatments and high costs of medication. They recommend subsidization of transportation costs and increased access to travel grants, especially for rural residents, as well as minimizing discrepancies in medication costs and developing mechanisms to offset these costs fairly to resolve such inequities. We identified that to improve socioeconomic and emotional well-being, patients may benefit from access to social programs, employment aid, financial support programs, and programs that provide physical assistance when they are displaced from family for HD.

Self-managed HD scheduling with increased flexibility may improve adherence and adverse outcomes in individuals receiving HD. Comparing individuals assigned Monday/Wednesday/Friday HD schedule with those assigned Tuesday/Thursday/Saturday demonstrated higher rates of skipped sessions (particularly on Saturdays), longer hospital stays, and increased mortality over a 12-month period in those on the Tuesday/Thursday/Saturday schedule.28

Our study has several strengths. The study population had a diverse range of demographic characteristics that broadly reflects the national HD population, which strengthens the generalizability of the findings. The involvement of patient partners in all phases of the study ensured that the priorities of individuals with first-hand experience of HD were incorporated into the interpretation of study results. Moreover, the inclusion of perspectives from health care providers in addition to those of people on HD and their caregivers helped us to consider the feasibility of implementing potential solutions in our health care system. Finally, we used the COREQ and GRIPP2 criteria for qualitative research checklists to systematically and comprehensively report on our qualitative study and to ensure inclusion of all pertinent information regarding patient involvement in our research.29,30

Limitations of this study include the involvement of only English-speaking participants, thus the application and transferability to non-English speaking individuals is uncertain. Participants were from HD units in large urban centers and thus findings may not be generalizable to smaller, rural settings. Our study focused on challenges to individualization in HD care in the Canadian setting; however, similarities in some of the challenges identified in non-Canadian studies suggest that our findings may also be relevant internationally.21,22 Finally, the solutions came largely from patients, caregivers, and health care providers. Very few decision-makers were involved in this study and thus the feasibility of implementing solutions in HD units across Canada is not fully elucidated.

Findings from the focus groups and interviews will inform the design of innovative solutions that we plan to trial in the future to address challenges to individualized care. To help guide which solutions we will move forward, we will use consensus methodology with our study team and the top 10 challenges to HD care that we identified through our priotizing workshop in phase 3 of the Triple I study (Table 3).31 Potential innovative solutions to explore include self-management of dialysis scheduling, as well as solutions that address the transportation gap. Implications for clinical care include the importance of considering individual patient preferences in terms of dialysis set-up (eg, moving the HD machine to the access side when possible) and providing equipment and materials to maximize comfort during HD treatments.

Table 3.

Top 10 Challenges to Address in In-Center Hemodialysis Care.

| 1 | Timing, frequency, and amount of information being received should be individualized (specific to each patient) |

| 2 | Improve continuity of care in hemodialysis and information about a patient’s care is complete in their chart |

| 3 | Improve the way information is communicated between health care providers and patients |

| 4 | It is frustrating for patients when they are told to see a family physician about health concerns they bring up in hemodialysis |

| 5 | More information and access to financial resources and support including availability of flexible, reliable, and affordable transport to/from hemodialysis, housing, and nutrition/diet |

| 6 | More flexibility to change hemodialysis spots/schedule |

| 7 | Better information about the pros and cons of different dialysis modalities |

| 8 | More information about health risks and other conditions associated with hemodialysis |

| 9 | Better information about transplant status |

| 10 | More information and access to social programs for people on hemodialysis |

In conclusion, this study has identified important challenges to individualization of in-center HD care and potential solutions to many of these challenges that can be applied in clinical care or pursued in research studies. In future phases of the Triple I study, we will use knowledge synthesis and consensus methodologies to identify, develop, and prioritize potential solutions for evaluation in clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all research participants and patient partners for their time and for sharing their perspectives. They also thank Corri Robb for transcribing the interviews and focus groups. The results presented in this paper have not been published in whole or in part elsewhere.

Footnotes

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: The study protocol was approved by the research ethics board at the University of Manitoba for the main Winnipeg site (HS20494 [H2017:049]), as well as the research ethics boards at the 4 other participating institutions (University of Calgary, University of Alberta, University of Ottawa, and Dalhousie University). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for Publication: All authors consent to publication.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data and materials are available from corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author Contributions: K.R., J.F., M.M., A.D., H.V., G.F., K.S., M.J., A.T., M.M.S., N.P., S.T., K.T., M.T., and C.B. contributed to research idea and study design. K.R., J.F., A.D., G.F., M.T., K.S., M.M.S., S.T., K.T., N.P. and C.B. contributed to data acquisition. K.R., J.F., M.M., A.D., H.V., G.F., M.T., P.F.D.S., K.S., M.T., R.S. and C.B. contributed to data analysis and interpretation. J.F., M.T., and C.B. were involved in supervision or mentorship. M.M., A.D., H.V., and G.F. were involved as patient partners. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision, accepts personal accountability for the author’s own contributions, and agrees to ensure that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: K.R., J.F., M.M., A.D., H.V., G.F., P.F.D.S., K.S., M.J., A.T., N.P., S.T., M.T., and C.B. declare that they have no relevant financial interests. Dr. Sood has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca. Dr. Tennankore has received advisory board and/or consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Otsuka, Jansen, and Baxter and unrestricted investigator-initiated grant funding from Astellas and Otsuka.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work is a project of the Canadians Seeking Solutions and Innovations to Overcome Chronic Kidney Disease (Can-SOLVE CKD) Network, which is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) under Canada’s Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research Grant 20R26070.

Dr. Tonelli is supported by a Foundation grant from the CIHR. Dr. Bohm is supported by the Manitoba Medical Services Foundation F.W. Du Val Clinical Research Professorship.

ORCID iDs: Matthew James  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1876-3917

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1876-3917

Clara Bohm  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7710-7162

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7710-7162

References

- 1. Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Guthrie B, et al. Comorbidity as a driver of adverse outcomes in people with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2015;88(4):859-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fraser SDS, Roderick PJ, May CR, et al. The burden of comorbidity in people with chronic kidney disease stage 3: a cohort study. BMC Nephrology. 2015;16(1):193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Webster AC, Nagler EV, Morton RL, Masson P. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet. 2017;389(10075):1238-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Jager DJ, Grootendorst DC, Jager KJ, et al. Cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality among patients starting dialysis. JAMA. 2009;302(16):1782-1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ. Clinical epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32(5, suppl 3):S112-S119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Culleton B, et al. Chronic kidney disease and mortality risk: a systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(7):2034-2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gorodetskaya I, Zenios S, McCulloch CE, et al. Health-related quality of life and estimates of utility in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2005;68(6):2801-2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Anderson CAM, Nguyen HA. Nutrition education in the care of patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2018;31(2):115-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Morton RL, Sellars M. From patient-centered to person-centered care for kidney diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(4):623-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bowling CB, O’Hare AM. Managing older adults with CKD: individualized versus disease-based approaches. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(2):293-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. O’Hare AM, Armistead N, Schrag WL, Diamond L, Moss AH. Patient-centered care: an opportunity to accomplish the “Three Aims” of the National Quality Strategy in the Medicare ESRD program. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(12):2189-2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bear RA, Stockie S. Patient engagement and patient-centred care in the management of advanced chronic kidney disease and chronic kidney failure. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2014;1:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sellars M, Clayton JM, Detering KM, Tong A, Power D, Morton RL. Costs and outcomes of advance care planning and end-of-life care for older adults with end-stage kidney disease: a person-centred decision analysis. Plos One. 2019;14(5):e0217787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levin A, Adams E, Barrett BJ, et al. Canadians Seeking Solutions and Innovations to Overcome Chronic Kidney Disease (Can-SOLVE CKD): form and function. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2018;5:2054358117749530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jacobsen M, O’Connor A, Stacey D. Decisional needs assessment in populations: a workbook for assessing patients’ and practitioners’ decision making needs. Ottawa, ON, Canada: University of Ottawa Google Scholar; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hsieh H, Shannon S. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description. Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. NVivo qualitative data analysis. 11th ed. QSR International Pty Ltd; Victoria, Australia; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Manns B, Hemmelgarn B, Lillie E, et al. Setting research priorities for patients on or nearing dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(10):1813-1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Newmann JM, Litchfield WE. Adequacy of dialysis: the patient’s role and patient concerns. Semin Nephrol. 2005;25(2):112-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wilkie M, Barnes T. Shared hemodialysis care: increasing patient involvement in center-based dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(9):1402-1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ellis E, Knapp S, Quan J, Sutton W, Regenstein M, Shafi T. Dialysis transportation: the intersection of transportation and Healthcare. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25385/dialysis-transportation-the-intersection-of-transportation-and-healthcare. Published 2019. Accessed October 21, 2020.

- 24. Iacono S. Transportation issues and their impact upon in-center hemodialysis. J Nephrol Soc Work. 2004;23:60-63. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chan KE, Thadhani RI, Maddux FW. Adherence barriers to chronic dialysis in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(11):2642-2648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in A. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27. The burden of out-of-pocket costs for Canadians with kidney failure: 2018 report. 2018 March Contract No. 3. Montreal, QC: The Kidney Foundation of Canada. Accessed June 30, 2020. www.kidney.ca/burden

- 28. Obialo C, Bashir K, Goring S, et al. Dialysis “no-shows” on Saturdays: implications of the weekly hemodialysis schedules on nonadherence and outcomes. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(4):412-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. Res Involv Engagem. 2017;3:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rossum K, Finlay J, McCormick M, et al. A mixed method investigation to determine priorities for improving information, interaction and individualization of care among individuals on in-centre hemodialysis: the Triple I Study. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2020;7:1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]