Abstract

Glucose is used aerobically and anaerobically to generate energy for cells. Glucose transporters (GLUTs) are transmembrane proteins that transport glucose across the cell membrane. Insulin promotes glucose utilization in part through promoting glucose entry into the skeletal and adipose tissues. This has been thought to be achieved through insulin-induced GLUT4 translocation from intracellular compartments to the cell membrane, which increases the overall rate of glucose flux into a cell. The insulin-induced GLUT4 translocation has been investigated extensively. Recently, significant progress has been made in our understanding of GLUT4 expression and translocation. Here, we summarized the methods and reagents used to determine the expression levels of Slc2a4 mRNA and GLUT4 protein, and GLUT4 translocation in the skeletal muscle, adipose tissues, heart and brain. Overall, a variety of methods such real-time polymerase chain reaction, immunohistochemistry, fluorescence microscopy, fusion proteins, stable cell line and transgenic animals have been used to answer particular questions related to GLUT4 system and insulin action. It seems that insulin-induced GLUT4 translocation can be observed in the heart and brain in addition to the skeletal muscle and adipocytes. Hormones other than insulin can induce GLUT4 translocation. Clearly, more studies of GLUT4 are warranted in the future to advance of our understanding of glucose homeostasis.

Keywords: Glucose transporter 4, Insulin, Skeletal muscle, Adipocytes, Brain, Heart, Antibodies

Core Tip: Glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) can be detected not only in the skeletal muscle and adipocytes, but also in the brain and heart. In addition to the translocation from vesicles in the cytosol to the cell membrane by insulin, the expression levels of Slc2a4 mRNA and GLUT4 proteins are also regulated by many factors. A variety of methods and antibodies from various sources have been used to evaluate GLUT4 expression and translocation.

INTRODUCTION

Currently, diabetes is a problem of public health[1]. Based on the American Diabetes Association definition, diabetes is a serious chronic health condition of your body that causes blood glucose levels to rise higher than normal, which will lead to multiple complications if hyperglycemia is left untreated or mismanaged[2]. Diabetes occurs when your body cannot make insulin or cannot effectively respond to insulin to regulate blood glucose level. There are two type of diabetes, insulin-dependent type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and -independent type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). T2DM accounts for about 90% to 95% of all diagnosed cases of diabetes, and is due to the lack of responses to insulin in the body[3]. Insulin resistance is a characteristic of T2DM. For a person with diabetes, a major challenge is to control or manage blood glucose level. Glucose is a common molecule used for production of energy or other metabolites in cells. As a quick energy source, glucose can be metabolized aerobically or anaerobically depending on the availability of oxygen or cell characteristics[4]. Glucose is a hydrophilic molecule, and cannot diffuse into or out of a cell freely. It needs transporters to cross the cell membrane. Glucose transporters (GLUTs) are proteins that serve this purpose.

GLUTs are members of the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporters, which are responsible for the transfer of a large array of small molecules such as nutrients, metabolites and toxins across the cell membrane[5]. Multiple members have been identified in each family of MFS transporters, and changes of their functions have been associated with a number of diseases[5]. Members of MFS transporters have 12 transmembrane helices, and transport their substrates as uniporters, symporters or antiporters[5]. Upon binding of the substrates on side of the membrane, a conformation change occurs, which is achieved through coordinative interactions of those helices through a “clamp-and-switch” mechanism. Structural studies have shown that the substrate specificity is achieved through the conserved amino acid residues within each family[5]. Thus, it is important to understand GLUT functions, expressions and regulations for the control of blood glucose homeostasis.

Insulin and GLUTs

Dietary starch is first digested into glucose before being absorbed into the body and utilized[4]. The first transporter identified is GLUT1, which is expressed universally in all cells, and responsible for basal glucose transport[6]. Insulin stimulates glucose utilization in the body. This is in part through the insulin-induced glucose uptake in the muscle and adipose tissues. In addition to insulin stimulation, physical activity can also increase glucose entering into the skeletal muscle cells[7]. The observation that insulin promotes the redistribution of GLUTs from intracellular locations to the plasma membrane in adipocytes began in the 1980s[8-10]. Few years later, the insulin-induced glucose transport was also found in muscle cells[11,12]. To understand the underlying mechanism of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake, antibodies against membrane glucose transport proteins were created[13]. Subcellular fractionation, cytokinin B (glucose-sensitive ligand), and glucose absorption into isolated vesicles were used to study the phenomenon. It was proposed that these GLUTs are moved from intracellular components to the plasma membrane of adipocytes and muscle cells upon insulin stimulation[6]. In 1988, a specific antibody against a GLUT sample preparation was created, which eventually led to the identification of a molecular clone that encodes an insulin-induced GLUT from mouse adipocytes[6]. It was named GLUT4. Since the 1990s, fluorescent-labeled fusion proteins, GLUT4-specific antibodies, photoaffinity labeling reagents, immunofluorescence microscopy, and high-resolution electron microscope have been used to confirm the insulin-induced translocation and underlying mechanisms[6]

It has been widely accepted that insulin mainly stimulates transfer of GLUT4 from intracellular storage vesicles to the plasma membrane. Insulin stimulation accelerates the movement rate of GLUT4 containing vesicles to the cell membrane[14]. When more GLUT4 is on the plasma membrane, more glucose enters the cells without any change of the GLUT4 specific activity. During insulin stimulation, GLUT4 is not statically maintained in the plasma membrane but continuously recycled[6]. After insulin is removed, the amount of GLUT4 on the plasma membrane drops and the rate of movement returns to basal level.

Since identification and cloning of GLUT1, 13 additional GLUTs have been cloned using recombinant DNA techniques[15]. Based on their phylogeny or genetic and structural similarities, GLUTs are classified into three classes. Class I includes GLUTs 1-4, and GLUT14 which are responsible for glucose transfer. Class II consists of GLTUs 5, 7, 9 and GLUT 11 which are considered as fructose transporters. Class III contains GLTUs 6, 8, 10, 12 and GLUT 13[16]. All GLUTs have nearly 500 amino acid residues that form 12 transmembrane helices[15].

Each GLUT has its own unique affinity and specificity for its substrate, tissue distribution, intracellular location, regulatory mechanisms and physiological functions[17]. The most well studied and known members are GLUTs 1-6. GLUT1 is found evenly distributed in the fetal tissues. In human adults, GLUT1 Level is high in erythrocytes and endothelial cells. It is responsible for basal glucose uptake[18]. GLUT2 is expressed in the liver and pancreas, and contributes to glucose sensing and homeostasis[17]. In enterocytes, GLUT2 is responsible to transport the absorbed glucose, fructose and galactose out of the basolateral membrane to enter into the blood circulation through the portal vein[19]. GLUT3 just like GLUT1 is expressed in almost all mammalian cells and is responsible for the basal uptake of glucose. GLUT3 is considered as the main GLUT isoform expressed in neurons and the placenta, but has also been detected in the testis, placenta, and skeletal muscle[20-22]. GLUT5 is specific for uptake of fructose in a passive diffusion manner, and is expressed in the small intestine, testes and kidney[17]. GLUT6 is expressed in the spleen, brain, and leukocytes as well as in muscle and adipose tissue[15,23]. GLUT6 has been shown to move from the intracellular locations and plasma membrane of rat adipocytes in a dynamin-dependent manner[23]. Table 1[24-57] summarizes names, numbers of amino acids, Kms, expression profiles and potential functions of those GLUTs.

Table 1.

Summary of glucose transporter family members

|

Protein (gene)

|

Amino acids

|

Km (mm)

|

Expression sites

|

Function/substrates

|

Ref.

|

| GLUT1 (SLC2A1) | 492 | 3-7 | Ubiquitous distribution in tissues and culture cells | Basal glucose uptake; glucose, galactose, glucosamine, mannose | [24-30] |

| GLUT2 (SLC2A2) | 524 | 17 | Liver, pancreas, brain, kidney, small intestine | High-capacity low-affinity transport; glucose, galactose, fructose, glucosamine, mannose | [25-27,29-34] |

| GLUT3 (SLC2A3) | 496 | 1.4 | Brain and nerves cells | Neuronal transport; glucose, galactose, mannose | [25-27,29,30,33-35] |

| GLUT4 (SLC2A4) | 509 | 5 | Muscle, fat, heart, hippocampal neurons | Insulin-regulated transport in muscle and fat; glucose, glucosamine | [25-27,29,31,36,37] |

| GLUT5 (SLC2A5) | 501 | 6 | Intestine, kidney, testis, brain | Fructose | [25-27,29,30,34,38-42] |

| GLUT6 (SLC2A6) | 507 | 5 | Spleen, leukocytes, brain | Glucose | [25-27,29,30,43] |

| GLUT7 (SLC2A7) | 524 | 0.3 | Small intestine, colon, testis, liver | Fructose and glucose | [25-27,29,30,38] |

| GLUT8 (SLC2A8) | 477 | 2 | Testis, blastocyst, brain, muscle, adipocytes | Insulin-responsive transport in blastocyst; glucose, fructose, galactose | [25-27,29,30,44,45] |

| GLUT9 (SLC2A9) | Major 540, Minor 512 | 0.9 | Liver, kidney | Glucose, fructose | [25-27,29,30,B46-48] |

| GLUT10 (SLC2A10) | 541 | 0.3 | Heart, lung, brain, skeletal muscle, placenta, liver, pancreas | Glucose and galactose | [25-27,29,30,48,49] |

| GLUT11 (SLC2A11) | 496 | 0.2 | Heart, muscle, adipose tissue, pancreas | Muscle-specific; fructose and glucose transporter | [25-27,29,30,50-54] |

| GLUT12 (SLC2A12) | 617 | 4-5 | Heart, prostate, skeletal muscle, fat, mammary gland | Glucose | [25-27,29,30,53,55] |

| GLUT13 (SLC2A13) | Rat 618, human 629 | 0.1 | Brain (neurons intracellular vesicles) | H+-myo-inositol transporter | [25-27,29,30,56] |

| GLUT14 (SLC2A14) | Short 497, Long 520 | unknown | Testis | Glucose transport | [25-27,29,30,57] |

GLUT4 gene, its tissue distribution, and physiological functions

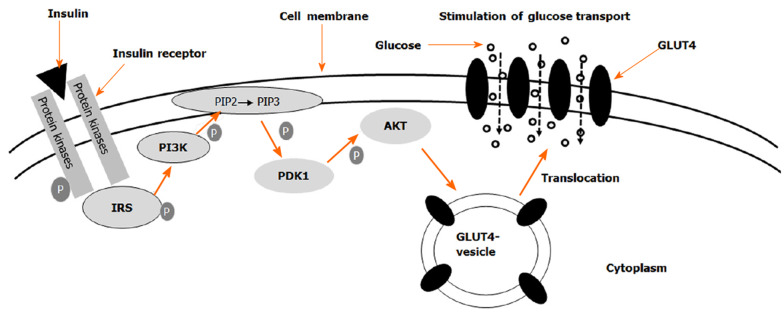

Human GLUT4 has 509 amino acid residues and is encoded by SLC2A4 gene in the human genome. It is mainly expressed in adipocytes and skeletal muscle. The unique N-terminal and COOH terminal sequences are responsible for GLUT4's response to insulin signaling and membrane transport[58]. The Km of GLUT4 is about 5 mmol/L. In response to insulin stimulation, intracellular vesicles containing GLUT4 are moved from cytosol to the cell membrane. As shown in Figure 1, insulin receptor is a tetramer with two alpha-subunits and two beta-subunits linked by disulfide bonds[59]. When insulin binds to its receptor on the cell membrane, insulin receptor beta subunits that contain tyrosine kinase domain autophosphorylate each other. The phosphorylated β-subunits recruit insulin receptor substrates (IRS) and phosphorylate them. Then phosphorylated IRSs bind to and activate phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) which is recruited to the plasma membrane and converts PIP2 to PIP3. On the plasma membrane, PI3K activates PIP3 dependent protein kinase, which phosphorylates and activates AKT (also referred to as protein kinase B, PKB). Akt activation triggers vesicle fusion, which results in the translocation of GLUT4 containing vesicles from intracellular compartments to the plasma membrane. The elevation of GLUT4 on the membrane leads to increase of glucose entry into the cell.

Figure 1.

Schematic of insulin-induced translocation of glucose transporter 4 from cytosol to the cell membrane. The binding of insulin to its receptors initiates a signal transduction cascade, which results in the activation of Akt. Akt acts on the glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) containing vesicles in the cytosol to facilitate their fusion with the cell membrane. When more GLUT4 molecules are present in the membrane, the rate of glucose uptake is elevated. GLUT4: Glucose transporter 4.

Upon refeeding, elevated glucose levels in the blood stimulates insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells. Insulin stimulates GLUT4 translocation to the cell membrane, which increases glucose uptake in cells, and achieves glucose homeostasis[60,61]. After the insulin stimulation disappears, GLUT4 is transferred back into the cytosol from the plasma membrane. More than 90% of GLUT4 is located in the intracellular body, trans-Golgi network, and heterogeneous tube-like vesicle structure, etc., which constitute the GLUT4 storage vesicle (GSV). In an unstimulated state, most GLUT4 is in the intracellular vesicles of muscle and adipocytes[62].

The amount of GLUT4 on the cell membrane is determined by the rate of the movement from intracellular GSV to the cell membrane. In adipocytes and skeletal muscle cells, insulin increases the rate of GLUT4 translocation from GSVs to membrane and decreases the rate of GLUT4 movement from membrane back to the vesicles, which lead to elevation of GLUT4 content on the cell membrane by 2-3 times[63]. Moreover, in adipocytes, insulin increases the GLUT4 recirculation to maintain a stable and releasable vesicle[64].

So far, insulin-induced GLUT4 translocation has been studied extensively. However, questions still remain. Methods and reagents used to determine the expression levels of GLUT4 and its translocation mechanism deserve to be summarized and analyzed. Therefore, we searched the relevant articles in PubMed and investigated the methods and reagents used in the studies. “Glucose transporter 4” and “GLUT4” as the protein and “SLC2A4” as the gene name were used as keywords in the search. In order to have a more clearly overview, we further divided and focused on the search into three parts, GLUT4 in the skeletal muscle, GLUT4 in adipose tissues, and GLUT4 in heart and brain.

GLUT4 IN THE SKELETAL MUSCLE

The term "muscle" covers a variety of cell types. Mammals have four main types of muscle cells: skeletal, heart, smooth, and myoepithelial cells. They are different in function, structure and development[65]. The skeletal muscle mass accounts for 40% of the total body mass, and the regulation of skeletal muscle glucose metabolism will significantly affect the body's glucose homeostasis[66,67]. Skeletal muscle is composed of many muscle fibers connected by collagen and reticular fibers. Each skeletal muscle fiber is a syncytium that derives from the fusion of many myoblasts. Myoblasts proliferate in large quantities, but once fused, they no longer divide. The fusion usually follows the onset of myoblast differentiation[65]. Different fiber types have distinct contractile and metabolic properties[68]. The skeletal muscle maintains skeletal structure and essential daily activities[69]. Also, it is a source of proteins that can be broken down into amino acids for the body to use.

Insulin stimulates glucose uptake and utilization in the skeletal muscle. GLUT4 plays a key role in the uptake process. Glucose can be stored as glycogen, which is used as a quick source of energy in physical activity[70]. In the skeletal muscle, exercise helps increase insulin sensitivity and stimulates SLC2A4 gene transcription[60]. Physiological factors such as the type of muscle fibers can also affect the GLUT4 Level. An increase in physical activity will induce the GLUT4 Levels, whereas a decrease in activity level will reduce GLUT4[68]. The skeletal muscle not only maintains the activities, but also regulates the glucose homeostasis in the body, which plays a key role in the development of metabolic diseases[69]. Obesity and T2DM have a negative impact on skeletal muscle glucose metabolism[71].

To review the methods and reagents of GLUT4 studies in skeletal muscle, "GLUT4, skeletal muscle" and "SLC2A4, skeletal muscle" as keywords were used to search the PubMed database to retrieve relevant articles. The skeletal muscle is a highly specialized tissue made of well-organized muscle fibers. The unique structural characteristic of muscle inherits difficulties to be lysed for biochemical studies. Therefore, we want to focus on the sample preparation of skeletal muscle in GLUT4 studies. The retrieved articles were screened mainly according to the research methods and reagents used for skeletal muscle preparation, experimental groups included, Slc2a4 mRNA and GLUT4 protein measurements and the source of GLUT4 antibodies obtained. In the end, 10 representative articles were selected for analysis and summary as shown in Table 2[72-81].

Table 2.

Recent studies of glucose transporter 4 expression and translocation in the skeletal muscle

|

Methods

|

Materials

|

Comparisons

|

Observations/conclusions

|

Ref.

|

| Western blot. | Cell fractions of rat L6 myotubes, 3T3-L1, and mouse muscle and adipose tissues. Anti-GLUT4 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (1:1000). | Cell: Total cell lysate vs membrane fractions. Mouse tissues: Control vs high-fat diets. | Insulin treatments increases GLUT4 levels in membrane fractions without any change in the total cell lysate. GLUT4 levels in adipose tissue and muscle of mice fed a high-fat diet are lower in all fractions than that fed the control diet. | [72] |

| Western blot. | Whole cell and cell fractions from rat L6 and mouse C2C12 muscle cells, and soleus muscle of hind limb from mice. Anti-GLUT4 from Santa Cruz. Biotechnology (1:1000). | Whole cell lysate vs membrane fractions. Treatments without or with insulin or AICAR. | GLUT4 translocation occurs in L6 myotubes and 3T3-L1 adipocytes stimulated by insulin and AICAR. GLUT4 translocation occurs in muscle at 15 to 30 minutes and in adipose tissue at 15 minutes after glucose treatment. | [73] |

| Western blot. | Giant sarcolemmal vesicles from soleus muscles of Sprague-Dawley rats. Anti-GLUT4 from Millipore (1:4000). | Tissue samples without or with insulin released in the presence of glucose as a stimulant and lipid as a control. | A glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide increases glucose transport and plasma membrane GLUT4 protein content. | [74] |

| Real-time PCR for Slc2a4 mRNA levels. | Total RNA of the skeletal muscle from male C57BL/6J and ICR mice fed different diets. | mRNA levels in muscle samples from mice fed the control or CLA supplement diet | Dietary CLA does not affect Slc2a4 mRNA levels in the mouse skeletal muscle | [75] |

| Western blot. | Preparations of sarcolemmal membrane fractions and crude lysates from male Muscovy ducklings. Anti-GLUT4 from East Acres (1:500). | GLUT4 from a unique crude membrane fraction of rat skeletal muscle was used as an arbitrary unit and from erythrocyte ghost as a negative control | Polyclonal antibodies detect a protein of similar size (approximately 45 kDa) of GLUT4 in the crude membrane preparations from rat (positive control) and duckling skeletal muscle. No signal was obtained for rat erythrocyte ghost membrane preparation. | [76] |

| ATB-BMPA-labelling of glucose transporters, Immunoprecipitation, liquid-scintillation counting, Western blot. | Tissue samples of isolated and perfused EDL or soleus muscle from GLUT1 transgenic C57BL’KsJ-Leprdbj and control mice. Anti-GLUT4 (R1184; C-terminal) from an unknown source. | Non-transgenic mice vs transgenic mice. | Basal levels of cell-surface GLUT4 in isolated or perfused EDL are similar in transgenic and non- transgenic mice. Insulin induces cell-surface GLUT4 by 2-fold in isolated EDL and by 6-fold in perfused EDL of both transgenic and non-transgenic mice. Western blot results were not shown. | [77] |

| Preembedding technique (immune reaction occurs prior to resin embedding to label GLUT4), and observations of whole mounts by immunofluorescence microscopy, or after sectioning by immunogold electron microscopy. | Muscle samples from male Wistar rats. Anti-GLUT4 (C-terminal, 1:1000), and anti-GLUT4 (13 N-terminal, 1:500) from unknown species. | Rats were divided in four groups: Control, contraction received saline, insulin and insulin plus contraction groups. They received glucose followed by insulin injection. | Two populations of intracellular GLUT4 vesicles are differentially recruited by insulin and muscle contractions. The increase in glucose transport by insulin and contractions in the skeletal muscle is due to an additive translocation to both the plasma membrane and T tubules. Unmasking of GLUT4 COOH-terminal epitopes and changes in T tubule diameters does not contribute to the increase in glucose transport. | [78] |

| Immunoprecipitation, and Western blot. | Membrane fractions from skeletal muscle of male Wistar rats treated without or with insulin. Anti-GLUT-4 from Genzyme, Anti-GLUT-4 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. | Crude membrane preparations and cytosolic fractions in samples of rats treated without or with insulin. | In vitro activation of PLD in crude membranes results in movement of GLUT4 to vesicles/microsomes. This GLUT4 translocation is blocked by the PLD inhibitor, neomycin, which also reduces insulin-stimulated glucose transport in rat soleus muscle. | [79] |

| Western blot for GLUT4 protein in homogenates of epitrochlearis muscles. Tissue slices labeled with 2-[1,2-3H]-deoxy-d-glucose and counted in a gamma counter. | Muscle homogenate and slices from male Sprague-Dawley rats. Anti- GLUT4 from Dr. Osamu Ezaki. | Sedentary control vs a 5-day swimming training group. | The change of insulin responsiveness after detraining is directly related to muscle GLUT-4 protein content. The greater the increase in GLUT-4 protein content induced by training, the longer an effect on insulin responsiveness lasts after training. | [80] |

| Immunofluorescence for membrane preparations, and 2-Deoxyglucose uptake in isolated skeletal muscles. | Membrane preparations from L6 cells over-expressing GLUT4myc. Isolated skeletal muscle samples from mice. Anti-GLUT4 from Biogenesis. | L6 cells over-expressing GLUT4myc treated without or with Indinavir. | HIV-1 protease inhibitor indinavir at 100 µmol/l inhibits 80% of basal and insulin-stimulated 2-deoxyglucose uptake in L6 myotubes with stable expression of GLUT4myc. | [81] |

AICAR: 5-aminoimidazole-4- carboxamide ribonucleotide; CLA: Conjugated linoleic acid; EDL: Extensor digitorum longus; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; ICR: Institute of Cancer Research; PLD: Phospholipase D; GLUT4: Glucose transporter 4.

Overall, the current research methods of GLUT 4 studies in skeletal muscle are listed below: (1) Samples were homogenized to prepare membrane fractions for analysis of GLUT 4 in western blot using monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies; (2) Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to determine the mRNA abundance of Slc2a4; (3) Immunocytochemical staining was used to detect GLUT4 in situ. The fibers were labeled for GLUT4 by a preembedding technique and observed as whole mounts by immunofluorescence microscopy or after sectioning, by immunogold electron microscopy. Preembedding is a technique to label GLUT4 immediately after tissues or cells are collected, which allows that the antibody interacts with the antigen before denaturation; (4) Muscle cell lines stably expressing tagged GLUT4 were established to study the translocation; and (5) Radiolabeled 2-deoxyglucose was used to determine the glucose uptake in muscle tissue slices.

The antibodies used in these articles were from Santa Cruz, Millipore, East Acres, Biogenesis and other sources not specified. Only two of the publications have a positive control group of GLUT4 expression using overexpression of a fusion protein and tissue preparation as a standard for determination. Positive controls are important when Western blot and fusion protein immunofluorescence methods are used to determine the GLUT4 protein levels.

According to studies summarized in Table 2, the following key points can be obtained. Insulin and muscle contraction increase glucose uptake in the skeletal muscle, which is associated with increases of GLUT4 content and its translocation. Neomycin, a phospholipase D inhibitor, blocks GLUT4 translocation. In the skeletal muscle isolated from GLUT1 transgenic mice, insulin-induced GLUT4 translocation response is lost, which is not due to down-regulation of GLUT4 expression. Conjugated linoleic acid in the diet does not affect the Slc2a4 mRNA expression in the skeletal muscle. Indinavir, an HIV-1 protease inhibitor, can block the glucose uptake mediated by GLUT4 in normal skeletal muscle and adipocytes without or with insulin stimulation. More studies are anticipated to elucidate how insulin resistance and T2DM affect the functions of GLUT4 system and whether overnutrition plays a role in it.

GLUT4 IN ADIPOSE TISSUES

The ability for an organism to store excessive amount of energy in the form of fat is helpful for it to navigate a condition of an uncertain supply of food[82]. Adipocytes, the main type of cells in adipose tissue, are not only a place for fat storage, but also endocrine cells to secrete cytokines for the regulation of whole body energy homeostasis[82]. Based on the mitochondrial content and physiological functions, adipocytes are divided into white, beige and brown fat cells. Structurally, 90% of the cell volume of a white adipocyte is occupied by lipid droplets. In normal-weight adults, white adipose tissue accounts for 15% to 20% of body weight[83,84]. Excessive accumulation of body fat results in the development of obesity, which can lead to the development of T2DM if not managed[85,86]. In addition, adipose tissues secrete cytokines such as leptin and adiponectin with abilities to regulate food intake and insulin sensitivity[87]. GLUT4 is expressed in adipocytes, where insulin stimulates its translocation from intracellular locations to the cell membrane, which leads to increase of glucose uptake[88]. High expression levels of GLUT4 in adipose tissue can enhance insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance[89].

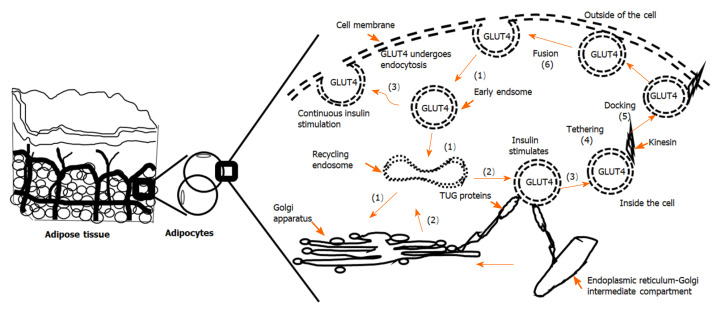

Insulin-induced GLUT4 translocation in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle has been studied extensively. Overall, in recent years, great progress has been made in the understanding of GLUT4 vesicles movement, the fusion of the vesicles with the cell membrane, and the translocation mechanism in response to insulin. As shown in Figure 2, in adipocytes of an adipose depot, GLUT4 vesicles move from the specialized intracellular compartment to the cell periphery (near cell membrane), which is followed by tethering and docking. Tethering is the interaction between GLUT4 vesicles and the plasma membrane. Docking is the assembly of the soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor-attachment protein (SNAP) receptor (SNARE) complex. Fusion occurs when the lipid bilayers of the vesicles with GLUT4 and the cell membrane merge[90]. The actin cytoskeleton system plays an important role in retaining GLUT4 vesicles in adipocytes. After insulin stimulation, remodeling of cortical actin causes the release GLUT4 vesicles to the plasma membrane[90-92]. β-catenin plays an important role in regulating the transport of synaptic vesicles. The amount of GLUT4 within the insulin sensitive pool is determined by the β-catenin levels in adipocytes, which allows GLUT4 translocate to the cell membrane in response to insulin stimulation[93,94].

Figure 2.

The movement of glucose transporter 4 in adipocytes. Adipose tissue is made of adipocytes. In adipocytes, glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) can be found in the cell membrane and in the cytosol. The translocation of GLUT4 from cytosolic vesicles to the cell membrane leads to elevated glucose uptake, whereas endocytosis brings GLUT4 back to the cytosol. (1): In unstimulated cells, GLUT4 containing membrane portions are internalized in an endocytosis manner to generate vesicles containing GLUT4. GLUT4 vesicles are internalized into early (or sorted) endosomes. They can enter the recovery endoplasmic body, and follow the retrograde pathway to the trans-Golgi network and endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi intermediate compartment or other donor membrane compartments. (2): GLUT4 vesicles derived from the donor membrane structures are secured by tether containing a UBX domain for GLUT4 (TUG) protein. (3): During insulin signal stimulation, GLUT4 vesicles are released and loaded onto the microtubule motor to be transferred to the plasma membrane. The continuous presence of insulin leads to the direct movement of these vesicles to the plasma membrane. (4): GLUT4 vesicles are tethered to motor protein kinesin and other proteins. A stable ternary SNARE complex forms when this occurs. (5): The stable ternary SNARE complex is docked on the target membrane. (6): The docked vesicles rely on SNARE to move to and fuse with the target membrane[60,90,94]. GLUT4: Glucose transporter 4.

To summarize the current methods and reagents used for GLUT4 analysis in adipose tissues and adipocytes, “GLUT4, 3T3-L1”, and “GLUT4, adipocytes” were used to search the literature published in the past 15 years. We ignored those studies that only measured Slc4a2 mRNA, lacked the focus on adipocytes, and did not have full text versions. The resulted 30 articles were analyzed and summarized in Tables 3[95-112] and 4[113-124]. Table 3 contains 18 articles and summarizes the effects of drugs or bioactive compounds on Slc2a4 mRNA and GLUT4 protein expressions, and GLUT4 translocation. Table 4 contains 12 articles and summarizes studies of the regulatory mechanisms of GLUT4 system.

Table 3.

Recent studies of effects of bioactive compounds and chemical drugs on glucose transporter 4 expression and translocation in adipocytes

|

Methods

|

Materials

|

Comparisons

|

Conclusions

|

Ref.

|

| Immunoprecipitation, dual fluorescence immunostaining, Western blot. | 3T3-L1, anti-GLUT4 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (1:200). | Treatments without or with kaempferitrin. | Kaempferitrin treatment upregulates total GLUT4 expression and its translocation in 3T3-L1 cells. | [95] |

| Subcellular fractionations, Western blot. | 3T3-L1, anti-GLUT4 from Cell Signaling Technology (1:1000). | Treatments without or with epigallocatechin gallate. | Green tea epigallocatechin gallate suppresses insulin-like growth factor-induced-glucose uptake via inhibition of GLUT4 translocation in 3T3-L1 cells. | [96] |

| Western blot. | 3T3-L1, anti-GLUT4 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. | Treatments without or with GW9662. | GW9662 increases the expression of GLUT4 protein in 3T3-L1 cells. | [97] |

| Immunoprecipitation, Western blot. | 3T3-L1, anti-GLUT4 from Chemicon. | Treatments without or with p38 inhibition. | Inhibition of p38 enhances glucose uptake through the regulation of GLUT4 expressions in 3T3-L1 cells. | [98] |

| Western blots, Real-time PCR, Electrophoretic mobility shift assay, Immunofluorescence. | Adipose tissues of Esr1 deletion and wild type female mice, 3T3-L1, anti-GLUT4 from Merck/Millipore for Western blot (1:4000), and for immunofluorescence (1:100). | Tissue and cells without or with gene deletion. | Estradiol stimulates adipocyte differentiation and Slc2a4 mRNA and GLUT4 protein expressions in an ESR1/CEBPA mediated manner in vitro and in vivo. | [99] |

| Real-time PCR, Solid-phase ELISA. | 3T3-L1, anti-GLUT4 antibody from Pierce (1:1000). | Treatments without or with the extract. | The crude extract of stevia leaf can enhance Slc2a4 mRNA and GLUT4 protein levels in 3T3-L1 cells. | [100] |

| GeXP multiplex for mRNA, Western blot. | 3T3-L1, anti-GLUT4 from Millipore (1:20). | Treatments without or with indicated reagents. | Curculigoside and ethyl acetate fractions increase glucose transport activity of 3T3-L1 adipocytes via GLUT4 translocation. | [101] |

| Real-time PCR, Western blot. | 3T3-L1, anti-GLUT4 from Cell Signaling Technology. | Treatments without or with luteolin | Luteolin treatment decreases Slc2a4 mRNA and GLUT4 protein levels in 3T3-L1 cells. | [102] |

| Western blot. | 3T3-L1, anti-GLUT4 from Abcam (ab654-250). | Treatments without or with extract. | Shilianhua extract treatment decreases GLUT4 protein level in 3T3-L1 cells. | [103] |

| Western blot. | 3T3-L1, and male C57BL/6J mice fed a normal-fat or high-fat diet, anti-mouse GLUT4 from AbD SeroTec (1:1000). | Treatments without or with fargesin. | Fargesin treatment increases GLUT4 protein expression in 3T3-L1 cells and adipose tissues of mice. | [104] |

| Western blot. | 3T3-L1, antibody no mentioned. | Treatments without or with phillyrin. | Phillyrin treatment increases the expression levels of GLUT4 protein in 3T3-L1 cells. | [105] |

| Real-time PCR, Western blot. | 3T3-L1, anti-GLUT4 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. | Treatments without or with 6Hydroxydaidzein. | 6Hydroxydaidzein facilitates GLUT4 protein translocation, but did not affect Slc2a4 mRNA level in 3T3-L1 cells. | [106] |

| Western blot. | 3T3-L1, and C57BL/6J mice with SirT1 and Ampkα1 knockdown, anti-GLUT4 from Signalway Antibody. | Treatments without or with indicated reagents. | Seleniumenriched exopolysaccharides produced by Enterobacter cloacae Z0206 increase the expression of GLUT4 protein in mice, but not in 3T3-L1 cells. | [107] |

| Western blot. | 3T3-L1, anti-GLUT4 from Cell Signaling Technology | Treatments without or with extract. | Aspalathin-enriched green rooibos extract increases GLUT4 protein expression in 3T3-L1 cells. | [108] |

| Transient expression of myc-GLUT4-GFP and fluorescence microscopy. | 3T3-L1, fusion protein only. | Treatments without or with indicated reagents. | Gallic acid can increase GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 cells. | [109] |

| Real-time PCR, Western blot. | 3T3-L1, anti GLUT4 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (1: 1000). | Treatments without or with Ginsenoside Re. | Ginsenoside Re promotes the translocation of GLUT4 by activating PPAR-γ2. Slc2a4 mRNA is not affected in 3T3-L1 cells. | [110] |

| Real-time PCR, GLUT4-myc7-GFP from retroviral vector, flow cytometry, fluorescence microscopy. | 3T3-L1 with knockdown of PPARγ, fusion protein. | Cells without or with knockdown. | Bone morphogenetic proteins 2 and 6 inhibit PPARγ expression, which increases total GLUT4 levels, but not GLUT4 translocation3T3-L1 cells. | [111] |

| Western blot, real-time PCR. | 3T3-L1, anti-GLUT4 antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (sc-1608). | Treatments without or with pulse or manipulations. | Glucose pulse (25 mM) increases GLUT4 expression. GLUT4 level is partially restored by increasing intracellular NAD/P levels. A liver X receptor element on Slc2a4 promoter is responsible for glucose-dependent transcription. | [112] |

GLUT4: Glucose transporter 4; AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase; CEBPA and C/EBP: CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha; ESR1: Estrogen receptor 1.

Table 4.

Recent studies of mechanisms of glucose transporter 4 expression and translocation in adipocytes

|

Methods

|

Materials

|

Comparisons

|

Observations/conclusions

|

Ref.

|

| Western blot, real-time PCR, Electrophoretic mobility shift assay. | 3T3-L1 pre and differentiated adipocytes. Anti-GLUT4 antibody from Chemicon (1:4,000). | Treatment groups without or with the antagonist. | CB1 receptor antagonist markedly increases Slc2a4 mRNA and GLUT4 protein levels in 3T3-L1 cells via NF-kB and SREBP-1 pathways. | [113] |

| Immunohistochemistry, Western blot, real-time PCR. | Brown adipose tissue of Arfrp1 flox/flox and Arfrp1 ad-/-mouse embryos (ED 18.5) and 3T3-L1 cells with knockdown of Arfrp1. Anti-GLUT4 without specifying the vendor (1:1000). | Mice without or with deletion, and 3T3-L1 cells without or with knockdown. | In Arfrp1 ad-/- adipocytes, GLUT4 protein accumulates on the cell membrane rather than staying intracellularly without any change of Slc2a4 mRNA. siRNA-mediated knockdown of Arfrp1 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes has a similar result and increases basal glucose uptake. | [114] |

| Real-time PCR, Western blot. | 3T3-L1 transfected with Mmu-miR-29a/b/c. Anti-GLUT4 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (SC-7938). | Cells with or without transfection. | Transfection of miR-29 family members inhibits Slc2a4 mRNA and GLUT4 protein levels in 3T3-L1 cells by inhibiting SPARC expression. | [115] |

| Northern blot, Western blot, Nuclear run-on assay for the rate of GLUT4 gene transcription. | 3T3-L1 pre and differentiated adipocytes. Rabbit polyclonal GLUT4 antibody form Chemicon. | Treatment groups without or with inhibitors. | Inhibitions of proteasome using Lactacystin and MG132 reduce Slc2a4 mRNA and GLUT4 protein levels in 3T3-L1 cells. | [116] |

| AFFX miRNA expression chips for mRNA, Western blot. | Human Omental adipose tissue, 3T3-L1 pre and differentiated adipocytes with miR-222 silenced by antisense oligonucleotides. Anti-GLUT4 from Abcam. | Groups without or with transfection. | High levels of estrogen reduce the expression and translocation of GLUT4 protein. miR -222 silencing dramatically increases the GLUT4 expression and the insulin-stimulated translocation of GLUT4 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. | [117] |

| Northern blot for mRNA, Western blot. | 3T3-L1 pre and differentiated adipocytes. Anti-GLUT4 from Chemicon. | Treatment groups without or with oxidative stress. | Oxidative stress mediated by hydrogen peroxide induces expressions of C/EBPα and δ, resulting in altered C/EBP-dimer composition on the GLUT4 promoter, which reduces GLUT4 mRNA and protein levels. | [118] |

| Real-time PCR, Western blot. | Human Subcutaneous pre and differentiated adipocytes from control and obese subjects, 3T3-L1 pre and differentiated adipocytes transfected with miR-155. Anti-GLUT4 from Abcam. | Primary pre and differentiated adipocytes from normal and obese subjects, and cells without or with transfection. | The level of SLC2A4 is reduced in obese people, and the expression of GLUT4 protein is reduced in 3T3-L1 cells and differentiated human mesenchymal stem cells transfected with miR-155. | [119] |

| HA-GLUT4-GFP from transfected lentiviral plasmid and analyzed by flow cytometry, and fluorescence microscopy. | 3T3-L1 pre and differentiated adipocytes with knockdown of Dennd4C. Fusion protein. | Groups without or with knockdown. | Knockdown of Dennd4C inhibits GLUT4 translocation, and over- expression of DENND4C slightly stimulates it. DENND4C is found in isolated GLUT4 vesicles. | [120] |

| HA-Glut4-GFP from transfected plasmid, and analyzed by flow cytometry, fluorescence microscopy | 3T3-L1 pre and differentiated adipocytes with AS160 knockdown.Fusion protein. | Groups without or with knockdown. | Akt regulates the rate of vesicle tethering/fusion by regulating the concentration of primed, and fusion-competent GSVs with the plasma membrane, but not changing the intrinsic rate constant for tethering/fusion. | [121] |

| HA-tagged GLUT4 by fluorescence microscopy, Western blots, Immune pulldown. | 3T3-L1 pre and differentiated adipocytes without or with GST-ClipR-59 transfection. Rabbit anti-GLUTlut4 from Millipore; Mouse monoclonal anti-GLUT4 from Cell Signaling Technology. | Pull down antibodies. | By interacting with AS160 and enhancing the association of AS160 with Akt, ClipR-59 promotes phosphorylation of AS160 and GLUT4 membrane translocation. | [122] |

| Transfection of GFP-GLUT4 and indirect immunofluorescence. | 3T3-L1 pre and differentiated adipocytes with siRNA knockdown of P-Rex1. Fusion protein. | Without or with knockdown. | P-Rex1 activates Rac1 in adipocytes, which leads to actin rearrangement, GLUT4 trafficking, increase of glucose uptake. | [123] |

| Transfection of GLUT4-eGFP plasmid and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. | 3T3-L1 pre and differentiated adipocytes. Fusion protein. | Treatment groups without or with activators. | AMPK-activated GLUT4 translocation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes is mediated through the insulin-signaling pathway distal to the site of activated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase or through a signaling system distinct from that activated by insulin. | [124] |

GLUT4: Glucose transporter 4; ARFRP1: ADP-ribosylation factor-related protein 1; AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase; AS160: Akt substrate of 160 kDa; CB1: Cannabinoid receptor 1; CEBPA and C/EBP: CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha; CLIPR-59: Cytoplasmic linker protein R-59; DENND4C: Differentially expressed in normal and neoplastic cells domain-containing protein 4C; GSV: GLUT4 storage vesicle; NF-Κb: Nuclear factor-κB; PREX1: Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate dependent Rac exchange factor 1; SPARC: Secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine; SREBP-1: Sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1.

There are 11 and 2 articles respectively using real-time PCR and Northern blot to evaluate Slc2a4 mRNA levels. Western blot and ELISA are used in 24 articles to detect GLUT4 protein content. The antibodies were from Santa Cruz (6), Millipore (3), Cell Signaling Technology (4), Chemicon (4), Abcam (3), Pierce (1), Oxford (1) and Signalway (1). Two articles did not indicate the antibody sources. One article used antibodies from two companies. Nine articles indicated the dilutions of antibodies, and only 3 articles included the production catalog number. Immunofluorescence was used to detect the content and translocation of GLUT4 protein in 9 articles. Three articles used flow cytometry to detect GLUT4 protein. Twenty four of these 30 articles directly assessed levels of Slc2a4 mRNA or GLUT4 protein. The remaining 6 of the 30 articles measured GLUT4 protein using fusion proteins. No article has a positive control group that uses overexpression of GLUT4 via a recombinant construct or purified recombinant GLUT4 protein.

As shown in Table 3, GLUT4 translocation, and Slc2a4 mRNA and GLUT4 expression levels in 3T3-L1 cells can be regulated by bioactive compounds, crude extract of herbs, agonists of nuclear receptors, proteins and chemical drugs. Sl2a4 mRNA or/and GLUT4 expressions in 3T3-L1 cells or adipose tissues can be increased by kaempferitrin, GW9662, inhibitor of p38 kinase, estradiol, crude extract of stevia leaf, fargesin, phillyrin, selenium-enriched exopolysaccharide, aspalathin-enriched green rooibos extract, bone morphogenetic proteins 2 and 6, and glucose pulse. On the other hand, Slc2a4 mRNA and GLUT4 protein levels can be reduced by luteolin, and shilianhua extract in 3T3-L1 cells. GLUT4 translocation can be enhanced by kaempferitrin, curculigoside and ethyl acetate fractions, gallic acid, 6-hydroxydaidzein and ginsenoside Re, and reduced by green tea epigallocatechin gallate.

As shown in Table 4, a variety of methods have been used to study the regulatory mechanisms of GLUT4 system. 3T3-L1 cells have been the major model in those studies. In addition to the insulin, pathways involved in the Slc2a4 gene expression, GLUT4 protein expression and its translocation include cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1), ADP-ribosylation factor-related protein 1, MiR-29 family, proteasome system, estrogen pathway, oxidative stress via CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha (C/EBPα), obesity development, differentially expressed in normal and neoplastic cells domain-containing protein 4C, nuclear factor-κB, Akt and Akt substrate of 160 kDa, phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate dependent Rac exchange factor 1, secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC), sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP-1), and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway. CB1 receptor antagonists increase Slc2a4 mRNA and GLUT4 protein expressions through NF-kB and SREBP-1 pathways. Akt pathway regulates the rate of vesicle tethering/fusion by controlling the concentration of primed, and fusion-competent GSVs with the plasma membrane. Inhibition of the SPARC expression reduces Slc2a4 mRNA and GLUT4 expressions. The expressions of C/EBPα and δ alter the C/EBP-dimer formation at the Slc2a4 gene promoter, which regulates its transcription. Inhibition of differentially expressed in normal and neoplastic cells domain-containing protein 4C can block GLUT4 translocation. Rac exchange factor 1 activation seems to promote GLUT4 translocation via arrangement of actin cytoskeleton. The mechanism of AMPK-mediated GLUT4 translocation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes seems to be distinct from that of insulin-induced one. Future studies are needed to integrate the roles of all these players in the regulation of GLUT4 system in adipocytes.

GLUT4 IN THE HEART

The heart works constantly to support the blood circulation throughout the lifespan. Cardiomyocytes constantly contract to pump blood, oxygen, metabolic substrates, and hormones to other parts of the body. This requires continuous ATP production for energy supply. The primary fuel for the heart is fatty acids, whereas glucose and lactate contribute to 30% of energy for ATP production[125]. In addition, glucose plays an important role in circumstances like ischemia, increased workload, and pressure overload hypertrophy.

Glucose is transported into cardiac myocytes through GLUTs. GLUT4 represents around 70% of the total glucose transport activities[15]. GLUT4 protein expression can be found as early as 21 days of gestation in rats[126]. The expression level of GLUT4 in the heart may increase or decrease depending on the different models. For example, GLUT4 protein content decreases along with aging in male Fischer rats, but increases 4-5 times in C57 Bl6 mice[127,128]. In basal state, GLUT4 is found mainly in intracellular membrane compartments, and can be stimulated by insulin and ischemia to translocate to the cell membrane[129]. The binding of myocyte enhancer factor-2 (MEF2) and thyroid hormone receptor alpha 1 is needed for transcription of Slc2a4 gene in cardiac and skeletal muscle in rats[130]. In addition, Slc2a4 gene expression can also be regulated by other transcription factors. For example, overexpression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 works with MEF2-C to induce Slc2a4 mRNA expression in L6 muscle cells[131]. Moreover, GLUT4 expression level can be affected by cardiovascular diseases, and myocardial sarcolemma, which reduce the expression and translocation of GLUT4[132]. The development of T1DM decreases GLUT4 expression level and its translocation in the heart of mice[132]. T2DM development also reduces GLUT4 content and translocation due to insulin resistance and impairments of insulin signaling pathway in human cardiomyocytes[133].

To investigate the methods and reagents used for GLUT4 studies in the heart, “GLUT4, heart”, and “cardiomyocytes, GLUT4 expression” were used as key words to search PubMed for articles published after 2000. We went through all papers with cardiomyocytes and GLUT4 in titles or short descriptions and selected 9 of them that are mainly focused on GLUT4 expression and translocation in the heart as shown in Table 5[134-142].

Table 5.

Recent studies of glucose transporter 4 expression and translocation in the heart

|

Methods

|

Materials

|

Comparisons

|

Conclusions

|

Ref.

|

| Western blot. | Cytosol and membrane fractions of left ventricular, heart, and blood from male Sprague-Dawley rats. Anti-GLUT4 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (1:200). | Groups without or with the indicated treatments. Na+/K+-ATPase and β-actin were loading controls of the membrane and cytosol fractions, respectively. Losartan was used as a positive control. | Ginsenoside Rb1 treatment can increase GLUT4 expression via inhibition of the TGF-β1/Smad and ERK pathways, and activation of the Akt pathway. | [134] |

| Real-time PCR,Western blot. | Isolated ventricular cells from heart of male adult (aged 6-8 wk) and neonatal (1-3 d old) Wistar rats.Anti GLUT4 from Abcam (unknown dilution). | Groups with or without the ethanol feeding. Gapdh and β-actin were included as loading controls for real-time PCR and Western blot, respectively. | Long-term (22 wk) ethanol consumption increases AMPK and MEF2 expressions, and reduces GLUT4 mRNA and protein expression in rat myocardium | [135] |

| Western Blot. | Isolated ventricular cells from heart of adult male Wistar rats. Polyclonal rabbit anti-human GLUT4 from AbD Serotec (4670–1704 1:750) | Groups with or without the indicated treatments. | Heart failure and MI reduce glucose uptake and utilization. GGF2 partially rescues GLUT4 translocation during MI. | [136] |

| Western blot, Immunofluorescence. | Isolated ventricular cells from heart of adult rats. Polyclonal anti-GLUT4 from Thermo Fisher Scientific (1:100). | Treatment groups were compared with that of 100 nM insulin. | Catestatin can induce AKT phosphorylation, stimulate glucose uptake, and increase GLUT4 translocation. | [137] |

| Western blot, Flow cytometric analysis. | Isolated ventricular cells from heart of adult male Wistar rats. Anti-GLUT4 (H-61) from unknow source (1:1000 for Western) and conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488. | Treatment groups with or without AMPK agonists. | AMPK activation does not affect GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake in isolated cardiomyocytes. | [138] |

| Real-time PCRUsing TaqMan® Gene Expression assays. | Blood, heart, frontal cortex cerebellum from male Wistar rats. | Tissues from control and diabetic rats. | Slc2a4’s expression is downregulated in STZ-treated rat’s heart, but unaffected in tissue protected by blood-brain barrier like frontal cortex. | [139] |

| Western blot, Immunohistochemistry. | Heart from male Sprague-Dawley rats, anti-GLUT4 from Cell Signaling Technology (2213, 1:1000), anti GLUT4 from Abcam (ab654, 1:200 for ICC/IF) | Treatment groups without or with the indicated treatments. | PEDF can increase glucose uptake and GLUT4 translocation in ischemic myocardium. | [140] |

| Real-time PCR,Western blot. | Heart from male wild type rats and SHRs. Rabbit polyclonal antibody GLUT4 from Millipore | Wild type rats and SHRs without or with the indicated treatments. | Sitagliptin upregulates levels of GLUT4 protein and Slc2a4 mRNA, and its translocation in cardiac muscles of SHRs. | [141] |

| Real-time PCR,Western blot. | Left ventricles muscle from male Wistar rats. Anti-GLUT4 from Chemicon (1:1000) | Saline as untreated control and reagent treated groups. | Growth hormone stimulates the translocation of GLUT4 to the cell membrane of cardiomyocytes in adult rats. | [142] |

GLUT4: Glucose transporter 4; AMPK: Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; ERK: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; GGF2: Glial growth factor 2; GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase; MEF2: Myocyte enhancer factor-2; MI: Myocardial infarction; PEDF: Pigment epithelium-derived factor; SHR: Spontaneously hypertensive rats; STZ: Streptozotocin; TGF: Transforming growth factors.

Rats are used in all 9 studies. Various methods and reagents are used to analyze Slc2a4 mRNA and GLUT4 protein levels in the heart and cardiomyocytes. Real-time PCR was used in 4 of them to determine Slc2a4 mRNA levels. Antibodies and Western blot were used to assess GLUT 4 protein in 8 of them. Immunohistochemistry was used in 1 of them. Two of them used immunofluorescence to track down GLUT4 translocation.

To determine the content of GLUT4 protein in the heart, Western blot and fusion protein immunofluorescence methods were used. As shown in Table 5, these studies do not include overexpressed GLUT4 or cell samples with Slc2a4 deletion as controls. Several of them did not mention sources of anti GLUT4 antibodies used in Western blots. Some used polyclonal antibodies, which may need a positive control to indicate the correct size and location of GLUT4 protein.

From the papers listed above, GLUT4 expression and translocation in the heart and cardiomyocytes can be affected through activations of ERK and Akt pathways. Proteins like growth hormone, catestatin or pigment epithelium-derived factor can stimulate GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake. Chemicals like sitagliptin and ethanol can up- and down-regulate Slc2a4’s mRNA expression levels, respectively. However, the underlying mechanisms responsible for these regulations of GLUT4 translocation and Slc2a4 mRNA expression remain to be revealed. In addition, the research results summarized here are from tissue and cells of rats. It will be interesting to see whether same results will be observed when tissues and cells from other animal models are used.

GLUT4 IN THE BRAIN

The brain is a complex organ in the body and controls a variety of functions from emotions to metabolism. It consists of cerebrum, the brainstem, and the cerebellum[143]. Brain cells utilize glucose constantly to produce energy in normal physiological conditions. The brain can consume about 120 g of glucose per day, which is about 420 kcal and accounts for 60% of glucose ingested in a human subject[125]. The glucose influx and metabolism in the brain can be affected by multiple factors such as aging, T2DM and Alzheimer’s disease[144]. Reduction of glucose metabolism in the brain can lead to cognitive deficits[145]. Due to the critical relationship between cognitive performance and glucose metabolism, it is important to understand the regulatory mechanism of glucose metabolism in the brain.

Studies have shown that insulin signaling can be impacted in both T2DM and Alzheimer’s disease[146,147]. Insulin is a key component for hippocampal memory process, and specifically involved in regulating hippocampal cognitive processes and metabolism[148]. Insulin-modulated glucose metabolism depends on regions in the brain. The cortex and hippocampus are the most sensitive areas in the brain[149]. Hippocampus located deeply in temporal lobe plays an important role in learning and memory, and relates to diseases like Alzheimer’s disease, short term memory loss and disorientation[150]. Hippocampal cognitive and metabolic impairments are relatively common in T2DM, which may be caused by diet-induced obesity and systemic insulin resistance[151]. On the other hand, insulin stimulation can enhance memory and cognitive function[152]. This enhancement may require the brain GLUT4 translocation as shown in rats[153]. It is very important to determine the expression profile of GLUT4 in the brain, and factors that impact GLUT4 expression and translocation.

To summarize methods and reagents used in brain GLUT4 studies, “brain, GLUT4 expression” were used as key words to search PubMed for articles that have brain and GLUT4 in their titles or short descriptions. Ten research articles published after 2000 were identified as representative ones, which are focused on GLUT4 translocations and content in the brain of rats and mice. We summarized the methods and reagents for GLUT4 analysis, and conclusions as shown in Table 6[154-163].

Table 6.

Recent studies of glucose transporter 4 expression and translocation in the brain

|

Methods

|

Materials

|

Comparisons

|

Conclusions

|

Ref.

|

| Western blot. | Brain, skeletal muscle, heart, and whiteadipose tissue from mice. Anti-GLUT4 from Chemicon (1:1000). | Samples from wild type and knockout mice. | Deletion of Slc2a4 in the brain leads to insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, and impaired glucose sensing in the VMH. | [154] |

| Western blot,Real time-PCR,Immunofluorescence. | Cortex, hypothalamus, cerebella samples from CD-1 mice. Monoclonal anti Glut4 (1F8) from Dr. Paul Pilch, Polyclonal anti Glut4 MC2A from Dr. Giulia Baldini, Polyclonal anti Glut4 αG4 from Dr. Samuel Cushman, Polyclonal anti Glut4 (C-20) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. | Expression profile in the mouse and rat brain samples. | Slc2a4 mRNA is expressed in cultured neurons. GLUT4 protein is highly expressed in the granular layer of the mouse cerebellum. GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane can be stimulated by physical activity. | [155] |

| Western blot. | Brian tissue from STZ-induced diabetic male Sprague-Dawley rats.Anti-GLUT4 from Millipore (1:1000). | Comparing treatment samples using β-actin and NA/K ATPase as loading controls in Western blot. | Chronic infusion of insulin into the VMH in poorly controlled diabetes is sufficient to normalize the sympathoadrenal response to hypoglycemia via restoration of GLUT4 expression. | [156] |

| Immunocytochemistry. | Cerebellum and hippocampus from male Sprague-Dawley rats.Rabbit anti-GLUT4 antibody from Alomone Labs (AGT-024, RRID: AB_2631197). | Identifying expression profile and translocation. | GLUT4 is expressed in neurons including nerve terminals.Exercising axons rely on translocation of GLUT4 to the cell membrane for metabolic homeostasis. | [157] |

| Real-time PCR, Immunocytochemistry. | Cerebral cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, cerebellum, medulla oblongata, cervical spinal cord, biceps muscles from male Wistar rats. Unknown source of antibody. | Identifying expression profile using β -actin as loading control in real-time PCR. | Slc2a4 mRNA is detected in many neurons located in brain and spinal cord. GLUT4 protein is detected in different regions of the CNS including certain allocortical regions, temporal lobe, hippocampus, and substantia nigra. | [158] |

| Immunocytochemistry, Western blot. | Brain, spleen, kidney from Lrrk2 knockout mice.Anti GLUT4 Avivasysbio (ARP43785_P050, 1:100), andanti GLUT4 from R&D Systems (MAB1262, 1:1000). | Samples from wild type and knockout mice, andanti-β-Tubulin as loading control. | Phosphorylation of Rab10 by LRRK2 is necessary for GLUT4 translocation.Lrrk2 deficiency increases GLUT4 expression on the cell surface in “aged” cells. | [159] |

| Western blot, Immunofluorescence, real-time PCR. | Brain from Cyp27Tg mice. Anti GLUT4 from Cell Signaling Technology (#2213,1:1000 dilution). | Mice with different treatments. | A reduction of GLUT4 protein expression in brain occurs after 27-OH cholesterol treatment. | [160] |

| Immunohistochemistry. | Brain, hypothalamus, and other tissues from Sprague–Dawley rats.Anti-GLUT4 antibody from Santa Cruz Biochemicals (1:200), Anti GLUT4 from S. Cushman (1:1000). | Identifying the expression profiles. Soleus muscle as GLUT4 positive control. Antibodies after pre-absorption with the corresponding synthetic peptide were used as negative control. for GLUT4 antibody. | GLUT4 is localized to the micro vessels comprising the blood brain barrier of the rat VMH.GLUT4 is co-expressed with both GLUT1 and zonula occludens-1 on the endothelial cells of these capillaries. | [161] |

| Electrophysiological analyses, fluorescent microscope. | Brain from GLUT4-EYFP transgenic mice. Fusion protein. | Comparing samples from treatments. A scrambled RNA expressed by AAV acted as a negative control. | GLUT4 neurons are responsible for glucose sensing. | [162] |

| Western blot,Immunohistochemistry. | Brain samples from 7, 11, 15, 21 and 60 d old Balb/c mice. Rabbit anti-rat GLUT4 from an unknow source (1:2500 dilution for Western and 1:2000 for immunohistochemistry). | Determine the expression profiles. Vinculin is used as the loading control in Western blot. | GLUT4 is expressed in neurons of the postnatal mouse brain. GLUT4 and GLUT8 may mediate the effects of insulin, or insulin-like growth factor on regulations of cognition, memory, behavior, motor activity and seizures. | [163] |

AAV: Adeno-associated virus; CNS: Central nervous system; CRR: Counterregulatory response; EYFP: Enhanced Yellow Fluorescent Protein; LRRK2: Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2; STZ: Streptozotocin; VMH: Ventromedial hypothalamus.

In these 10 papers, two of them used real-time PCR to determine the Slc2a4 mRNA in the brain. Eight of them used anti-GLUT4 antibodies and Western blot to detect GLUT 4 protein. Five papers included β-actin as loading control in Western blot. Four used immunohistochemistry. One paper used electrophysiological technique, and one paper used fluorescent microscopy to identify GLUT 4 in neurons. One study used brain specific Slc2a4 knockout and wild type mice to study the functions of GLUT4 in the brain.

In conclusion, results of Western blot and real-time PCR demonstrate that GLUT4 protein and Slc2a4 mRNA can be detected in rat’s brain and central nervous system. Deletion of Slc2a4 in the brain causes insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, and impaired glucose sensing in the ventromedial hypothalamus. GLUT4 mediates the effects of insulin, or insulin-like growth factor on regulations of cognition, memory, behavior, motor activity and seizures. GLUT4 positive neurons are responsible for glucose sensing. Physical activity improves GLUT4 translocation in neurons, a process that needs Rab10 phosphorylation. Interestingly, 27-OH cholesterol treatment seems to decrease GLUT4 expression in the brain. Studies of Slc2a4 mRNA and GLUT4 protein in the brain and central nervous system have begun to demonstrate the potential roles of GLUT4 expression and its translocation in the regulation of glucose metabolism in the brain and central nervous system. More studies of GLUT4 expression and translocation in the control of functions and metabolism in various region in the brain and central nervous system are expected in the future.

CONCLUSION

GLUT4 is generally thought to contribute to insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in adipocytes and skeletal muscle. Studies summarized here seem to show that GLUT4 is also expressed in the brain, neurons, and heart. GLUT4 is expressed concurrently with other GLUTs in multiple tissues in a temporal and spatial specific manner such as during brain development[163]. Hormones and cytokines other than insulin can also regulate the expression levels and translocation of GLUT4 in different tissues[141,142,163]. In adipocytes alone, many bioactive compounds or chemical reagents have shown to affect GLUT4 pathways as shown in Table 3. All these seem to indicate that the regulatory mechanism of the GLUT4 pathway is complicated than we originally proposed.

So far, various methods from gene knockout to immunohistochemistry have been used to study the mechanisms of Slc2a4 mRNA and GLUT4 expressions, and its translocation in different cells. Every technique has its pros and cons. Based on the studies summarized here, anti-GLUT4 antibodies from a variety of sources have been used to study GLUT4 expression and translocation. The conclusions of these studies are based on the experimental results derived from the use of those antibodies. A positive control derived from a cell or tissue with unique overexpression or silencing of GLUT4 is critical to confirm the antibody’s specificity to pick up a right signaling in the study system. This is especially true for Western blot. It appears that some of the studies did not include control groups like this. Another challenge facing biochemical study of GLUT4 translocation in the muscle may be the sample processing. This probably explains why fusion proteins and stable cell lines are developed to enhance signals and specificities for detection. Confirmation of the antibody specificity in a particular system probably should be done first.

As glucose homeostasis is a complicate process involved in many players. It is anticipated to see that many proteins seem to play a role in the regulation of GLUT4 system. It will be interesting to see how GLUT4 in different regions of the brain contributes to the regulation of glucose metabolism, and what the roles of insulin-induced GLUT4 translocation in those areas are. In addition, other GLUTs are also expressed in the same cells that GLUT4 are expressed. How GLUT4 works with other GLUTs to regulate metabolism also deserves to be investigated. Last, as glucose usage in the skeletal muscle is altered in insulin resistance and T2DM, how GLUT4 system contributes to progressions and interventions of these diseases still remains to be the focus in the future. Nevertheless, further understanding GLUT4 system will be very helpful for us to combat the development of T2DM.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the Department of Nutrition at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville for financial support to T.W. G.C. would like to thank Yantai Zestern Biotechnique Co. LTD for the research funding support.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest to report.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: June 26, 2020

First decision: August 9, 2020

Article in press: September 22, 2020

Specialty type: Biochemistry and molecular biology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Merigo F, Salceda R, Soriano-Ursúa MA S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Tiannan Wang, Department of Nutrition, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996, United States.

Jing Wang, College of Pharmacy, South-Central University for Nationalities, Wuhan 430074, Hubei Province, China.

Xinge Hu, Department of Nutrition, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996, United States.

Xian-Ju Huang, College of Pharmacy, South-Central University for Nationalities, Wuhan 430074, Hubei Province, China.

Guo-Xun Chen, Department of Nutrition, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996, United States. gchen6@utk.edu.

References

- 1.Al-Lawati JA. Diabetes Mellitus: A Local and Global Public Health Emergency! Oman Med J. 2017;32:177–179. doi: 10.5001/omj.2017.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.La Flamme KE, Mor G, Gong D, La Tempa T, Fusaro VA, Grimes CA, Desai TA. Nanoporous alumina capsules for cellular macroencapsulation: transport and biocompatibility. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2005;7:684–694. doi: 10.1089/dia.2005.7.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salt IP, Johnson G, Ashcroft SJ, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase is activated by low glucose in cell lines derived from pancreatic beta cells, and may regulate insulin release. Biochem J. 1998;335 (Pt 3):533–539. doi: 10.1042/bj3350533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stipanuk MH, Caudill MA. Biochemical, Physiological, and Molecular Aspects of Human Nutrition. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2012: 968. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quistgaard EM, Löw C, Guettou F, Nordlund P. Understanding transport by the major facilitator superfamily (MFS): structures pave the way. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:123–132. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klip A, McGraw TE, James DE. Thirty sweet years of GLUT4. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:11369–11381. doi: 10.1074/jbc.REV119.008351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richter EA, Derave W, Wojtaszewski JF. Glucose, exercise and insulin: emerging concepts. J Physiol. 2001;535:313–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-2-00313.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cushman SW, Wardzala LJ. Potential mechanism of insulin action on glucose transport in the isolated rat adipose cell. Apparent translocation of intracellular transport systems to the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:4758–4762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki K, Kono T. Evidence that insulin causes translocation of glucose transport activity to the plasma membrane from an intracellular storage site. Proc Natl Acad Sci . 77:2542–2545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wardzala LJ, Cushman SW, Salans LB. Mechanism of insulin action on glucose transport in the isolated rat adipose cell. Enhancement of the number of functional transport systems. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:8002–8005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klip A, Ramlal T, Young DA, Holloszy JO. Insulin-induced translocation of glucose transporters in rat hindlimb muscles. FEBS Lett. 1987;224:224–230. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wardzala LJ, Jeanrenaud B. Potential mechanism of insulin action on glucose transport in the isolated rat diaphragm. Apparent translocation of intracellular transport units to the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:7090–7093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James DE, Brown R, Navarro J, Pilch PF. Insulin-regulatable tissues express a unique insulin-sensitive glucose transport protein. Nature. 1988;333:183–185. doi: 10.1038/333183a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olson AL. Regulation of GLUT4 and Insulin-Dependent Glucose Flux. ISRN Mol Biol. 2012;2012:856987. doi: 10.5402/2012/856987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mueckler M, Thorens B. The SLC2 (GLUT) family of membrane transporters. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:121–138. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen L, Tuo B, Dong H. Regulation of Intestinal Glucose Absorption by Ion Channels and Transporters. Nutrients. 2016;8 doi: 10.3390/nu8010043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Navale AM, Paranjape AN. Glucose transporters: physiological and pathological roles. Biophys Rev. 2016;8:5–9. doi: 10.1007/s12551-015-0186-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grefner NM, Gromova LV, Gruzdkov AA, Komissarchik YY. Interaction of glucose transporters SGLT1 and GLUT2 with cytoskeleton in enterocytes and Caco2 cells during hexose absorption. Cell and Tissue Biol . 2015;9:45–52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gropper S, Smith J, Carr T. Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism. 7th ed. Publisher: Wadsworth Publishing, 2016: 640. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bell GI, Kayano T, Buse JB, Burant CF, Takeda J, Lin D, Fukumoto H, Seino S. Molecular biology of mammalian glucose transporters. Diabetes Care. 1990;13:198–208. doi: 10.2337/diacare.13.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haber RS, Weinstein SP, O'Boyle E, Morgello S. Tissue distribution of the human GLUT3 glucose transporter. Endocrinology. 1993;132:2538–2543. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.6.8504756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stuart CA, Wen G, Gustafson WC, Thompson EA. Comparison of GLUT1, GLUT3, and GLUT4 mRNA and the subcellular distribution of their proteins in normal human muscle. Metabolism. 2000;49:1604–1609. doi: 10.1053/meta.2000.18559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lisinski I, Schürmann A, Joost HG, Cushman SW, Al-Hasani H. Targeting of GLUT6 (formerly GLUT9) and GLUT8 in rat adipose cells. Biochem J. 2001;358:517–522. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3580517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takata K, Kasahara T, Kasahara M, Ezaki O, Hirano H. Erythrocyte/HepG2-type glucose transporter is concentrated in cells of blood-tissue barriers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;173:67–73. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joost HG, Thorens B. The extended GLUT-family of sugar/polyol transport facilitators: nomenclature, sequence characteristics, and potential function of its novel members (review) Mol Membr Biol. 2001;18:247–256. doi: 10.1080/09687680110090456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao FQ, Keating AF. Functional properties and genomics of glucose transporters. Curr Genomics. 2007;8:113–128. doi: 10.2174/138920207780368187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. 27 Szablewski L. Glucose Homeostasis and Insulin Resistance. Bentham Science Publishers, 2011: 211. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hruz PW, Mueckler MM. Structural analysis of the GLUT1 facilitative glucose transporter (review) Mol Membr Biol. 2001;18:183–193. doi: 10.1080/09687680110072140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheeseman C, Long WL. Structure of, and functional insight into the GLUT family of membrane transporters. Cell Health Cytoskeleton. 2015;7:167. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olson AL, Pessin JE. Structure, function, and regulation of the mammalian facilitative glucose transporter gene family. Annu Rev Nutr. 1996;16:235–256. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.16.070196.001315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uldry M, Ibberson M, Hosokawa M, Thorens B. GLUT2 is a high affinity glucosamine transporter. FEBS Lett. 2002;524:199–203. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson JH, Newgard CB, Milburn JL, Lodish HF, Thorens B. The high Km glucose transporter of islets of Langerhans is functionally similar to the low affinity transporter of liver and has an identical primary sequence. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:6548–6551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colville CA, Seatter MJ, Jess TJ, Gould GW, Thomas HM. Kinetic analysis of the liver-type (GLUT2) and brain-type (GLUT3) glucose transporters in Xenopus oocytes: substrate specificities and effects of transport inhibitors. Biochem J. 1993;290 (Pt 3):701–706. doi: 10.1042/bj2900701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Longo N, Elsas LJ. Human glucose transporters. Adv Pediatr. 1998;45:293–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kayano T, Fukumoto H, Eddy RL, Fan YS, Byers MG, Shows TB, Bell GI. Evidence for a family of human glucose transporter-like proteins. Sequence and gene localization of a protein expressed in fetal skeletal muscle and other tissues. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:15245–15248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kasahara T, Kasahara M. Characterization of rat Glut4 glucose transporter expressed in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: comparison with Glut1 glucose transporter. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1324:111–119. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(96)00217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fukumoto H, Kayano T, Buse JB, Edwards Y, Pilch PF, Bell GI, Seino S. Cloning and characterization of the major insulin-responsive glucose transporter expressed in human skeletal muscle and other insulin-responsive tissues. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:7776–7779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Q, Manolescu A, Ritzel M, Yao S, Slugoski M, Young JD, Chen XZ, Cheeseman CI. Cloning and functional characterization of the human GLUT7 isoform SLC2A7 from the small intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G236–G242. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00396.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burant CF, Takeda J, Brot-Laroche E, Bell GI, Davidson NO. Fructose transporter in human spermatozoa and small intestine is GLUT5. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14523–14526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drozdowski LA, Thomson AB. Intestinal sugar transport. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1657–1670. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i11.1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Douard V, Ferraris RP. Regulation of the fructose transporter GLUT5 in health and disease. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E227–E237. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90245.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rand EB, Depaoli AM, Davidson NO, Bell GI, Burant CF. Sequence, tissue distribution, and functional characterization of the rat fructose transporter GLUT5. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:G1169–G1176. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1993.264.6.G1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doege H, Bocianski A, Joost HG, Schürmann A. Activity and genomic organization of human glucose transporter 9 (GLUT9), a novel member of the family of sugar-transport facilitators predominantly expressed in brain and leucocytes. Biochem J. 2000;350 Pt 3:771–776. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmidt S, Joost HG, Schürmann A. GLUT8, the enigmatic intracellular hexose transporter. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E614–E618. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.91019.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ibberson M, Uldry M, Thorens B. GLUTX1, a novel mammalian glucose transporter expressed in the central nervous system and insulin-sensitive tissues. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4607–4612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phay JE, Hussain HB, Moley JF. Cloning and expression analysis of a novel member of the facilitative glucose transporter family, SLC2A9 (GLUT9) Genomics. 2000;66:217–220. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Augustin R, Carayannopoulos MO, Dowd LO, Phay JE, Moley JF, Moley KH. Identification and characterization of human glucose transporter-like protein-9 (GLUT9): alternative splicing alters trafficking. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16229–16236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dawson PA, Mychaleckyj JC, Fossey SC, Mihic SJ, Craddock AL, Bowden DW. Sequence and functional analysis of GLUT10: a glucose transporter in the Type 2 diabetes-linked region of chromosome 20q12-13.1. Mol Genet Metab. 2001;74:186–199. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2001.3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McVie-Wylie AJ, Lamson DR, Chen YT. Molecular cloning of a novel member of the GLUT family of transporters, SLC2a10 (GLUT10), localized on chromosome 20q13.1: a candidate gene for NIDDM susceptibility. Genomics. 2001;72:113–117. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Doege H, Bocianski A, Scheepers A, Axer H, Eckel J, Joost HG, Schürmann A. Characterization of human glucose transporter (GLUT) 11 (encoded by SLC2A11), a novel sugar-transport facilitator specifically expressed in heart and skeletal muscle. Biochem J. 2001;359:443–449. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scheepers A, Schmidt S, Manolescu A, Cheeseman CI, Bell A, Zahn C, Joost HG, Schürmann A. Characterization of the human SLC2A11 (GLUT11) gene: alternative promoter usage, function, expression, and subcellular distribution of three isoforms, and lack of mouse orthologue. Mol Membr Biol. 2005;22:339–351. doi: 10.1080/09687860500166143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu X, Li W, Sharma V, Godzik A, Freeze HH. Cloning and characterization of glucose transporter 11, a novel sugar transporter that is alternatively spliced in various tissues. Mol Genet Metab. 2002;76:37–45. doi: 10.1016/s1096-7192(02)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manolescu AR, Witkowska K, Kinnaird A, Cessford T, Cheeseman C. Facilitated hexose transporters: new perspectives on form and function. Physiology (Bethesda) 2007;22:234–240. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00011.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]